Strategic Assessment

In this paper we seek to define the effects of demography in its broadest sense on issues of national security, and to present a structured theoretical framework that can explain their mutual interactions and effects. The goal is to integrate the various interpretations presented in the articles of this special issue, which is devoted to demography and national security.

Israel is a unique and important test case for examining the interface between demography and national security, as a country that since its establishment has been strikingly demographically inferior to its environment, in a challenging and complex security situation, and subject to ongoing existential threats. Israel is a small nation state that survives in a situation of entrenched and ongoing ethnic-national-religious conflict with the Palestinians, while a consistently relatively large minority of some 20% of its citizens are identified as part of the Palestinian people, with whom Israel is in conflict.

We will explore the demographic impact on Israel’s national security through four main dimensions, which indicate the close links between demography and security (demography in Israel, demography between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean, demography within the regional context, and the demography of Diaspora Jewry). A theoretical model is also proposed, which apart from the explanation it provides for demographic impact (the independent variable), lays the foundation for further discussion of the possible effects of mediating variables on demography.

Keywords: demography, national security, the Israeli-Palestinian dispute, regional issues, Israel-Diaspora relations

Introduction

From the earliest days of the Zionist movement the demographic issue has occupied the political thinking of its leaders and shaped their attitude towards the project of settling the land, defining and developing a state. In fact, since the “Zionism of Zion” resolution passed by the Zionist Federation in 1905, and particularly from the creation of the British Mandate for Palestine until 1951, demographic considerations were dominant and decisive in shaping Zionist policy (Halamish 2024). Thus the demographic issue was one of the main factors in the historical and strategic decision by David Ben-Gurion, towards the end of the War of Independence, not to conquer the territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. After the Six Day War as well, the demographic question formed the basis of government discussions on the future of the captured territories and how to manage the lives of the Palestinian population and Jerusalem, when the sense of victory was quickly replaced by concern at the demographic change in the form of a million Arab residents in the territories. Thus Levi Eshkol’s government reached a decision (that was not implemented during its term) to settle Jews in the West Bank in order to create facts on the ground with continuity of settlement, which was intended not only to create strategic security depth but also to bring about demographic change within the state’s new borders (Miller-Katav 2024).

In this article we try to define the influence of demography on national security. In our reference to demography we depart from the narrow meaning of the term, which refers to the size and composition of a population based on agreed criteria of growth or decline, and the presentation of future trends based on demographic models. We have chosen to relate to the term in a broader sense, including reference to aspects of refugees, tensions between minorities and between ethnic and religious groups and their impact on government stability, processes of urbanization, and essential economic resources such as water and energy, and more.

Apart from determining that “Israel’s demographic statistics (like those of other countries) are part of the basic data on which its national security is based. Its [Israel’s] human capital is the basis of the society’s capabilities, the state product, and the construction of the security system” (Even 2020, 165), we will also engage with four different dimensions of demography: demography in Israel (majority-minority relations, in terms of national, religious, socioeconomic, center-periphery aspects and so on); the demography between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea (Israelis/ Palestinians); the regional demography of the surrounding states; and the demography of Diaspora Jewry. The influence of each dimension and their interactions point to the close links between demography and national security.

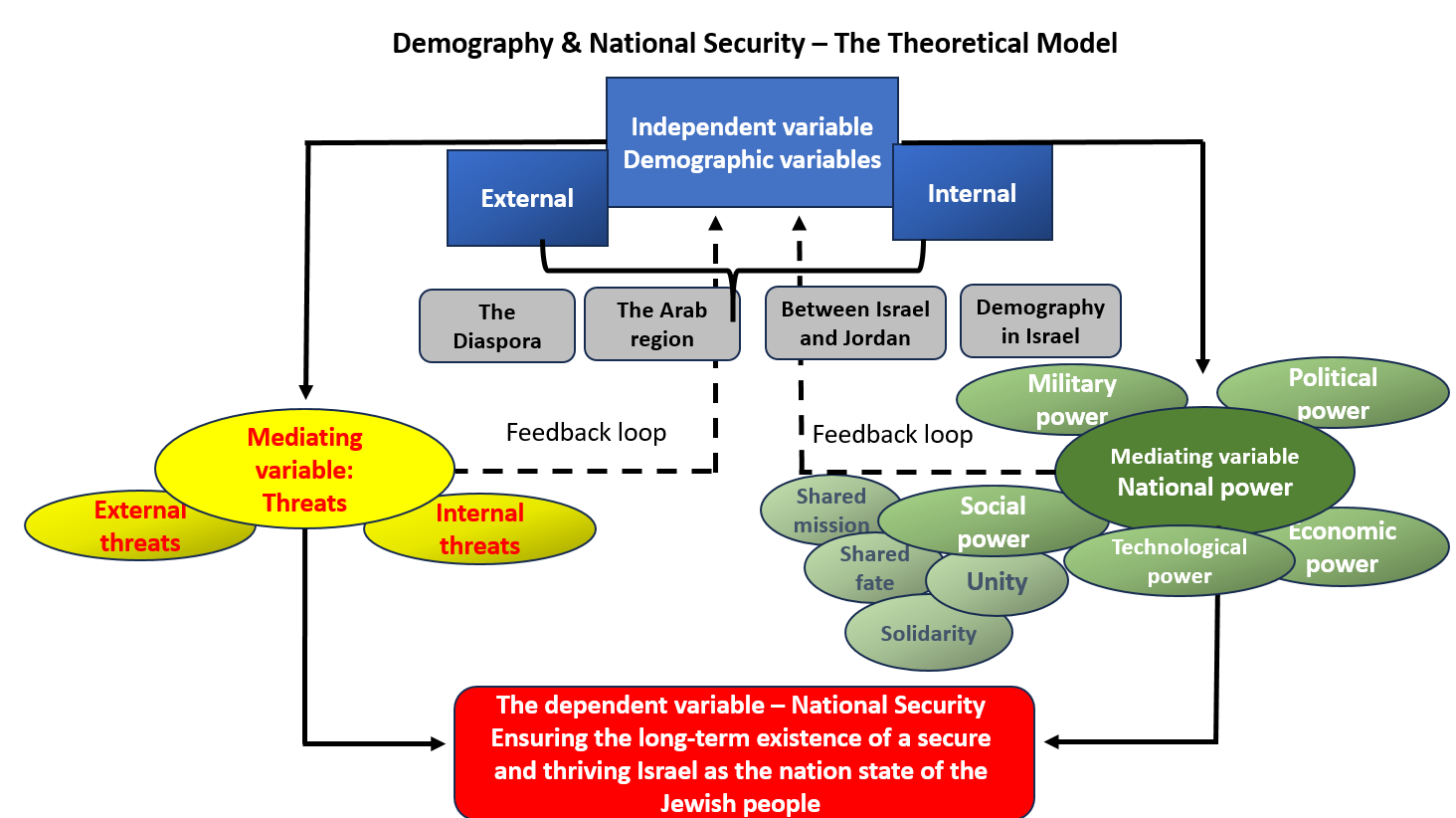

We also present a theoretical model, which apart from its proposed explanation of the effect of demography (the independent variable, classified into two groups of variables: internal and external, reflecting the four dimensions of our present analysis) on variables (national power and threats) that mediate national security (the dependent variable), also lays the groundwork for further discussion on the possible impact of those mediating variables on demography. This article focuses on the impact of demography on national security, but the analysis and development of the model led to an insight on the possibility of a feedback loop in the sense of the impact of the mediating variables on the independent variable, which we chose to present as a possibility, leaving the discussion of this possibility for another article.

The Interfaces and Links Between Demography and National Security

Demography is garnering increased attention within international relations and security studies (Tragaki 2011, 437). The purpose of national security is “to ensure the nation’s existence and protect its vital interests. Existence is the basic subject of security” (Tal 1996, 15). Therefore a national security risk is any event, process, trend or development that damages the state’s ability to function over time and ensure the security and welfare of its population, providing it with essential services at a decent level and protecting the sovereignty of its strategic assets (Yadlin 2021, 11).

Demography is defined as the study of population composition, dispersion and changes in size, and their effect on processes of policy-making and politics. While prominent social trends are usually unexpected and hard to predict, demographic developments are the exception to this rule. As soon as a demographic development is identified, it is apparently possible to predict with some certainty (in our assessment this statement is too deterministic, due to the familiar and important failures of demographic forecasts) how it will continue to develop (Goerres & Vanhuysse 2021, 2-5). For example, it is possible to forecast that in the twenty-first century the population of European countries will age—a trend that raises questions over the ability of these states to maintain their generous welfare policies (ibid., 16). Similar forecasts and concerns for welfare policy apply in Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea (Klein & Mosler 2021, 195) and China (Noesselt 2021, 117), while in Africa there is a reverse demographic process (Hartman & Biira 2021, 219). At the national level, demography is concerned with a historic analysis of the four main demographic parameters—fertility, mortality, internal migration and external migration—but also with forecasts that provide the basis for national planning (Winkler 2022).

While demography is obviously an important and vital subject for the analysis of future trends and formation of national policy, the question remains over the place of demography in matters of national security and its impact on decision-making and security strategy. In fact, demography provides a framework for an analysis of the effects of population characteristics and trends on national security, and an assessment of the impact of such trends on global conflicts in the developing world over the next twenty years (Sciubba 2012, 67). Demographic changes and population growth, together with overcrowding and lack of resources, lead to political, social, economic and environmental problems, and accelerate processes of state failure, which in turn can lead to internal conflicts that can spread beyond the state borders, and thus endanger regional stability (Georgakis Abbott and Stivachtis, 1999, 101-102). Moreover, demographic research is essential for deciding how to manage crises that affect national security, such as large scale natural disasters and epidemics. “It is important to state that the pandemic [Covid] stressed the importance of demographic data for crisis management […] The crisis revealed the need for more detailed data, in real time” (Even 2020, 164).

We also note that the link between demographic issues and national security issues finds expression in both the military power derived from the size of the army and the quality of its personnel (the larger the country, the greater its ability to maintain a large, high quality and stronger army) and in its economic power. Indeed demography certainly affects a country’s economic power, for good or bad (Krebs & Levy 2001, 64-69).

A focus on demographic changes can enable decision makers to identify trends and the emergence of security threats, and predict how these threats could lead to other problems (Goldstone 2002). Onn Winkler (2004) distinguishes between four main types of demographic threat: the first—when the majority feels threatened by a minority demanding full or partial independence, such as cultural and political autonomy; the second—when there is a fear of the country being overwhelmed by migrants of other religions or ethnic origins, leading to changes in the cultural-religious-ethnic character of the host country; the third—religious or ethnic struggles for priority in the country; the fourth—the age structure of the population, leading to low rates of participation in the work force.

Demographic trends and developments can drive processes that affect national resilience as well as the nature of threats to national security. These influences can be negative or positive, threats or opportunities. But in every case it is important to understand the trends and processes, to trace them and understand their significance for national security, so that it is possible to prepare in advance how to deal with them. The unique character of Israel derives from the fact that it is a relatively small national state, distinct from the Arab national states that surround it, and exists in a situation of striking demographic inferiority compared to the Arab states, in the shadow of an entrenched and long lasting ethnic-national-religious conflict with the Palestinians, who have ethnic and religious ties to Arab states, while a relatively large minority of some 20% of the citizens of Israel are identified as members of the Palestinian people, who are hostile to Israel. In addition, as a country that since its establishment has lived in a challenging and complex security situation under an ongoing existential threat, Israel has become a unique and important test case for all aspects of the interfaces between demography and national security.

The impact of demography on national security is expressed not only in the domestic sphere (Della-Pergola 2024) but also in the regional theatre. “Demographic data in the Middle East has significant influence on the features of Israel’s regional environment, including the stability of the surrounding countries, particularly those with broad demographic diversity” (Even 2020, 166). Demographic diversity affects the stability of central government, particularly where it is controlled by a minority group (like the Alawites in Syria), and in cases of tensions between different groups over the identity and borders of the state (Miller 2024) and its power structure (such as the demographic tension between Palestinians and Bedouin in Jordan, between Shiites and Sunnis in Bahrain, and more).

Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben Gurion, shaped the concept of its national security with reference to its demographic inferiority alongside its advantages in the field of human capital compared to the surrounding states. He noted that both population dispersal within its territory and national unity were important components of defending the borders of the Jewish state (Even 2021, 29). As with many other aspects of Israel’s security, its small size means that even relatively small demographic changes can have unforeseen and threatening political consequences. In this context, the definition of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state “obliges it to maintain a demographic balance with an absolute Jewish majority” (Even 2020, 166). Demography had decisive impact when the Israeli government decided to build the separation barrier dividing it from the Palestinian majority living in the West Bank (Toft 2012, 1), as well as the fence along the border with Egypt, with the aim of preventing refugees and labor migrants from entering the country, but it also affected the policy of encouraging fertility and Jewish immigration.

Here we aim to examine the demographic influence on national security through four dimensions of demography, where the impact of each one separately and the interactions between them indicate the close links between demography and national security.

The Four Demographic Dimensions with Reference to Israel’s National Security

The four dimensions are: the internal dimension; between Jordan and the Sea—Israel and the Palestinians; the regional dimension; Israel and Diaspora Jewry.

The Internal Dimension

The overall demographic balance between Jews and Arabs within the state of Israel is a vital component of Israel’s security and future as a Jewish and democratic state, which needs a solid Jewish majority to maintain this identity. In societies that exist in a situation of entrenched and ongoing national conflict (for a survey of this concept see Coleman 2006), the dominant group must have a firm demographic majority to maintain stability. This also applies to the case of Israel in the shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, where most of its Arab citizens define themselves as members of the Palestinian people and identify with the Palestinians who are in conflict with Israel. Since a majority of Arab Israelis and their leaders still object to the existence of Israel as a Jewish state (Raved 2018), the heads of the state over the years, including Yitzhak Rabin and Benjamin Netanyahu, believed that a solid Jewish majority within the borders of the sovereign state was essential to ensure its identity and existence as the nation state of the Jewish people (Wertman 2021; Ravid 2011; Michael and Wertman 2023).

According to estimates from the Central Bureau of Statistics, as of the end of 2023 there were about 9.84 million people living in Israel, of whom 7.21 million were Jews, 73.2% of the total, 2.08 million were Arabs, representing 21.1% of the whole, and 554,000 were others—non-Arab Christians and people not classified by religion in the Population Register, most of whom are not recognized as Jews by Halacha or identify themselves as part of the Jewish majority—, representing 5.7% of the whole (CBS 2023). While the fertility rate of Jewish women is three children on average, the fertility rate of Arab women is lower at 2.8 (CBS 2022), although fertility in the Bedouin population is higher than among the Jews—an average of 5.3 children per woman (Even 2021, 33). Forecasts show that by the second half of the twenty-first century, there should be a considerable Jewish majority within the borders of Israel (including those who are not recognized as Jews by Halacha) of almost 80%, due largely to the lower birth rate of Arabs in Israel—a figure that illustrates that the threat of losing the country’s Jewish identity is not on the horizon (Della-Pergola 2024).

In the absence of a threat to Israel’s Jewish character from the Arab minority, there are numerous claims referring to another demographic threat; that of the growth and separate, non-productive lifestyle of the Haredi Jewish population in Israel, which could eventually pose a security threat to the country’s economic power, rendering it poor and backward (Ilan 2019; Ben-David and Kimchi 2023) In addition to the socioeconomic issue, the fact that a large proportion of Haredi Jews do not serve in the IDF or in the Reserves, compared to the non-Haredi Jewish population, is very worrying for Israel’s future ability to maintain a sufficiently large army, certainly after October 7, 2023 when it became clear that the required large and strong army relies heavily on the Reserves (Rubinstein and Azulai 2024). In 2020 the non-Haredi Jewish population amounted to about two thirds of the Jewish population as a whole, but in another three decades it is expected to shrink to 55% (Della-Pergola 2024). This demographic dynamic highlights deep divisions within Israeli society about equal sharing of the burden of military service (Karni 2024), and this could undermine the unity of Israeli society and affect national resilience, which is an important element of national security.

At the end of 2023 there were 1.34 million Haredi Jews in Israel, representing 14% of the total population. The fertility rate in Haredi society is 6.4 children per woman, more than 2.5 times that of a non-Haredi Jewish woman, who gives birth to 2.5 children on average. If this fertility rate is maintained, in 2065 the Haredi population is expected to constitute 32% of the Israeli population, and 40% of Israeli Jews will be Haredi (Kahaner and Malach 2023, 14-15). However, it appears that the main challenge does not lie in the natural increase of Haredi society but in the gap in its level of education and employment compared to the population in general. The general level of Haredi education (core studies enabling integration into the labor market) is not good news for the future of the Israeli economy or the ability of Haredim to enter the job market with professions that contribute to high economic growth, since only 16% of Haredi pupils are eligible for a matriculation certificate, compared to 86% of pupils in the national and national-religious education systems (Ben-David and Kimchi 2023, 3, 8-9; Kahaner and Malach 2023, 29).

On the other hand, there is data showing positive trends in the integration of Haredi Jews into Israeli society, such as the fast rate of increase of Haredi students in institutions of higher education, which reached 258% in the years 2010-2023, compared to a 17% rise in the overall number of students in the same period. However, while Haredim constitute 14% of the population, they comprise only 5% of the total student body—showing that in spite of the positive trend, the road to full integration of Haredi society is still long (Kahaner and Malach 2023, 33-34).

There is also a positive trend in the rate of Haredi employment. In 2002 the rate of employment in Haredi society stood at 42%, while in 2022 it reached 66%, compared to 85% among non-Haredi Jews and 79% among the population as a whole. In fact, the gap is mainly due to men in the Haredi sector, of whom 55% are working, compared to 87% of non-Haredi Jewish men, while the rate of employment of Haredi women is almost the same as that of non-Haredi Jewish women—79.5% compared to 83% (Kahaner and Malach 2023, 61-63).

In addition to these two demographic aspects, it is important to note differences in population dispersal—between the center and the periphery of the country—, and to analyze their significance for opportunities regarding education, employment, standard and quality of life. The process of population centralization does not threaten the sovereignty of most countries worldwide, whose borders are recognized by the international community, but Israel is an exception. Israel’s Muslim Arabs, who as stated constitute 20% of the population and do not identify with the Zionist vision, see themselves as part of the Palestinian nation and are concentrated mainly in the periphery—this has special significance for state security (Sofer and Bistrov 2008). Moreover, a high concentration of population in a limited area creates vulnerability in times of war, particularly given its contemporary characteristics involving the threat of precision rockets and missiles such as armed drones. In the circumstances of Israel’s current demographic dispersal, with most of the population and national infrastructures concentrated in a narrow, vulnerable area, the probability of widespread damage to crucial targets is far higher.

Strengthening the population of the periphery will have a significant impact on Israel’s economy and productive capacity, reduce social gaps, and reinforce social solidarity and unity, which in turn will effect national resilience. The demographic aspects of population dispersal are also significant for maintaining state land and strengthening the border areas, which contributes indirectly to the security of borders and the traffic arteries that are essential for transporting troops during emergencies, as well as aid and rescue forces in cases of environmental disaster.

To sum up, while there is no demographic threat from Israeli Arabs to the identity of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state in the foreseeable future, the Haredi population represents a serious challenge to national security. Haredi society has come a long way in terms of narrowing the gaps between it and non-Haredi Jewish society, on which the Israeli economy and the IDF rely, but in spite of the positive trend and in view of the high natural growth rate of the Haredi population, it must do more to catch up in terms of employment rates and educational standards, and of course in IDF enlistment rates, to share the military and economic burden and ensure that Israel can successfully meet the whole range of its security and socioeconomic challenges. These demographic aspects, like those of population dispersal and others, affect various components of Israel’s capacity to ensure national security.

Between Jordan and the Sea—Israel and the Palestinians

The dispute between Israel and the Palestinians, which began at the end of the nineteenth century, has always featured demographic elements (Zureik 2003, 619). While it appears that Israel will retain a solid Jewish majority in the foreseeable future, the figures show that when the Palestinians living within the Palestinian Authority area and the Gaza Strip are taken into account, the Jewish majority between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River will disappear within a decade. In view of the equal numbers of Jews and Arabs in the whole area of Mandate Palestine, it is clear that in the absence of a clear separation between the peoples, the demographic issue will become an existential threat to the Jewish state. In fact, the demographic discussion has become the core of the political-strategic discourse on the future of Israel as the democratic nation state of the Jewish people. There are those who warn of the loss of the Jewish majority, leading to the loss of the state’s Jewish identity or to an apartheid regime, noting the difference in civic status between residents of the geographical area identified with the state even if official sovereignty is not applied to the whole. But others interpret the demographic trends and their significance, and the required course of action, in a different way (Ettinger 2006; Michael 2014; Milstein 2022; Sofer 2006; Abulof 2014; Lustick 2013). According to the more pessimistic view, Israel has only one option in order to maintain its Jewish and democratic identity and character, and that is the two-state solution. Others argue that there are other possible solutions. Some of them claim that a model of Palestinian autonomy could be the response, while a minority support the annexation of land, granting permanent residency to Palestinians with a long and stringent path to obtaining citizenship (like the East Jerusalem model or similar), and there are also those who wish to apply Israeli sovereignty to all the territories and would not hesitate to grant Israeli citizenship to the Palestinians.

Most of Israel’s leaders over the years have understood the danger inherent in the demographic threat and therefore chose to block the threat of a binational state. This is what Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin did with his decision to promote the Oslo process with the PLO in the years 1993-1995, based on a desire to create a separation between Israel and the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and thus safeguard Israel’s Jewish and democratic future (Wertman 2021). Rabin declared that:

I am one of those who do not want to annex 1.7 million Palestinians as citizens of Israel. Therefore I am against what is called Greater Israel […] In the present circumstances, between a binational state and a Jewish state, I prefer a Jewish state. The application of sovereignty to the whole of Mandatory Palestine means that we will have seven million Palestinian citizens within the State of Israel. It may perhaps be a Jewish state with respect to its borders, but binational in its content, demography and democracy […] Therefore I am against annexation (Neria 2016, 25-26).

This was also a central component of the decision by Prime Minister Ariel Sharon to implement unilateral separation from the Gaza Strip in 2005 (Even 2021, 38; Sofer 2006a). The demographic threat and the desire to avoid a binational state have similarly been a guideline in the strategic considerations of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with regard to the conflict (Michael and Wertman 2023). “With the renewal of the political process we have two main objectives: to prevent the creation of a binational state between the Sea and the Jordan River, which endangers the future of the Jewish state, and to prevent the establishment of another terrorist state under the patronage of Iran within Israel’s borders, which would be no less dangerous for us,” he declared (Tivon 2013).

The Regional Dimension

Israel is situated in the middle of a large Arab-dominated region with a population largely hostile to it, even in the countries at peace with it, and where its enemy states have not come to terms with Israel’s right to exist, or even the fact of its existence. Iran, a non-Arab country, represents the most significant threat to Israel and openly calls for its destruction. Iran’s demographic features are complicated and include disturbing basic characteristics or trends, with the emphasis on the Shiite population, but also trends with positive potential in terms of the regime’s stability and attitudes to Israel (Zamir 2022, 27). A thorough study of Iran’s demographic features could help provide an understanding of trends in the development of the threat it poses, as well as identify the areas of opportunities and chances for positive change from Israel’s perspective, particularly where it is possible to exploit demographic developments to undermine the regime.

Demography in the region has enormous impact on Israel’s security. Demographic data indicates the stability of regimes, societies and economies as well as migration trends. For example, demographic growth in Egypt affects its economy and stability; demographic tension in Jordan affects the stability of the Royal family and the Kingdom’s survival; Syrian demography was one of the reasons for the civil war and has an effect on the country’s stability and governance, while the Syrian refugees are undermining status-quo in countries such as Lebanon and Jordan. Thus the demographic shifts of the Middle East have “material impact on the features of Israel’s regional environment, including the stability of surrounding countries, particularly those where there is a broad demographic range” (Even 2020, 166).

In the case of Middle Eastern countries, the greater the demographic range, the greater the potential for political instability. This is true in general for countries such as Iran with its numerous minorities, Iraq, Yemen and even Turkey. It becomes even more significant in cases where a minority group holds the reins of government. For example, Jordan contains a large number of Palestinians compared to the Bedouin population, which is the source of power for the central government, Syria is ruled by the powerful Alawite minority, and Bahrain by the Sunni minority.

Demographic diversity alongside uncontrolled demographic growth leads to social and political tensions and economic crises. Egypt is a prominent example of a country where crises of food, water and environment are becoming more frequent and severe, and the situation is similar in Jordan, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon (Sofer 2006c). Regime instability, economic and ecological crises, and social and security tensions with demographic causes, lead to increases in migrants and refugees. Israel experienced the arrival of work-seeking migrants and refugees from Africa until 2012 (Even 2020, 176). Before the construction of the fence along the Egyptian border, Israel faced numerous attempts at entry by Palestinian refugees from Syria, along with threats of refugee entry from the Lebanese border. The fragile situation in the area and the spread of political failure in countries along Israel’s borders and across the region (for more on the political failures in the Arab world see: Michael and Gozansky 2016) present Israel with a complex challenge of uncontrolled migration.

“As a Jewish country with a small area and population, it is hard for Israel to absorb large scale non-Jewish migration” (Even 2020, 176). More seriously, Israel’s migration policy has not yet been developed as a component of its concept of internal and national security. The authorities in Israel lack sufficient demographic information about the population of work-seeking migrants and refugees in Israel, and in some cases we have seen outbreaks of violence that threaten public security. For example,

The extreme violence in the clashes between supporters and opponents of the regime in Eritrea in the heart of Tel Aviv […]This exceptionally violent incident highlights the significant holes in the (lack of) Israel’s migrant policy and the difficult consequences of the absence of a national domestic security strategy […] [The violence] is another striking example of a systemic failure, the lack of orderly migration policy, the defective function of the Israel Police and its structural weakness, the absence of a sufficient basis of [demographic] information to understand the situation, identify trends and give warnings in good time (Siboni and Michael 2023).

Demographic trends in the United States and Europe that affect their social and political structure can also have an impact on Israel (Even 2020, 166). While Israel is an island state situated in a challenging and partly hostile region, it is also linked economically, culturally and strategically to countries of the west—the United States and Europe. Therefore, any demographic changes in those regions could have possibly far-reaching effects on their relations with Israel. Demographic changes in the United States lead to political changes, particularly among voters for the Democratic party, and such changes send out signals relating to Israel from the progressive wing of the party, which has become larger and more influential. This also applies to the growth of the Muslim, Hispanic and other communities, some of whom are very critical of Israel, while others do not identify with it like the communities of voters from a decade or more ago, and this can affect the identity of future presidents and the degree of their support and that of their parties for Israel. There are those who have already identified the first signs of this during the Obama presidency, and even more so during the Biden administration (Gilboa 2020b).

While Israel’s special relationship with the United States is a central pillar of its national security, any demographic developments and trends are therefore of serious significance. Any erosion or damage to the relationship causes huge national damage to Israel, its regional and international status, and its ability to handle both security and political threats.

Israel and Diaspora Jewry

Israel’s unique situation as the only nation state of the Jewish people gives the demographic issue enormous importance in the connection between Israel and Diaspora Jewry. It is particularly relevant with respect to the Jews in the United States, who represent an extensive demographic reserve that without doubt could lead to a change in the demographic balance within Israel and between the River and the Sea, in favor of the Jews and economic growth in Israel, as occurred following the immigration of Jews from the former Soviet Union during the 1990s (Dvir 2020; Lan 2020; Leshem 2009). And even if they remain in the United States, the Jews there are a strategic advantage for Israel’s security (Gilboa 2020a; News1 2021). They are integrated into American society and leadership, and have great impact in matters of politics, economy, culture and more. The relationship between Israel and United States Jewry has always been a central anchor in the ability of both to develop and thrive since the establishment of the State of Israel, and it is essential not only for Israel’s security but for the security of the Jewish world as a whole (Yadlin 2018, 9-10). Even before the establishment of the state, the Jews of the United States played a decisive role in maintaining its national security, by means of support that included help in purchasing military equipment and recruiting political support in American politics (Lesansky 2018, 70-71; Shapiro 2018, 15).

However today there are tensions between Israel and United States Jewry against a background of disagreements on socioreligious issues, mainly over political matters, and above all Israel’s policy towards the Palestinians, which is perceived by most American Jews, who traditionally support the Democratic party, as mistaken and preventing the possibility of a resolution of the dispute based on the two-state formula (Shalom 2018, 120; Shapiro 2018, 16). The attitude of the US Jewish public to the transfer of the American Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem is a good illustration of the gap between the Jewish public in Israel and their American counterparts, only 16% of whom expressed support for the immediate move of the Embassy to Jerusalem (Shalom 2018, 104).

Others argue that the problem does not lie in Israeli policy but in a change in the character of American Jewry, which compared to other Jewish communities in places like Britain and Australia, which have very high internal resilience, displays less solidarity with the Jewish state (Abrams 2016). Whatever the case, Jews in the United States are divided more than ever on subjects relating to American and Israeli politics, illustrated by the growing split over questions of politics and values, where Israel is at the center of the controversies (Lasansky 2018, 94). Therefore there are some who warn that “the growing distance between the US Jewish community and Israel on one hand, and Israel’s retreat from its obligation to the Jewish people in the Diaspora on the other hand, signifies a danger to Israel’s natural strategic depth” (Orion and Ilam 2018, 27).

The October 7 massacre, together with the unshakeable support for Israel by the United States, could certainly have a positive effect on the sense of solidarity with Israel felt by American Jews (Della-Pergola 2024), but it is possible that the differences will return with the growing tensions between the Israeli government and the Biden administration over the continuation of the campaign against Hamas and plans for the day after (Eichner 2024). In spite of these differences, the support and activity of Jewish communities in the United States and the world are an important component of Israel’s national security.

The demography of the Jewish people is of great national interest, since Israel is the state of the Jewish people and because immigration from Jewish and Israeli communities overseas has a huge impact on the Jewish-Palestinian demography within the country […] Aliyah to Israel—has been one of the fundamental principles of the Zionist movement and the State of Israel, from its establishment to the present. It affects its foreign policy and its security, the nature of its efforts to provide information, immigrant absorption, settlement and infrastructures […] The migration balance of Israelis moving overseas—this too is an important demographic element […] Some of the emigrants leaving Israel have very high skills (“brain drain”), and this could also affect national security” (Even 2020, 169, 171).

As of 2023, there are about 15.7 million Jews in the world, of whom 46%, some 7.2 million, live in Israel. The second largest concentration of Jews is in the United States, with about 6.3 million. While 86% of the world’s Jews reside in Israel and the United States, the remainder are split between several countries, mainly in the west: 440,000 in France, 398,000 in Canada, 312,000 in Britain, 171,000 in Argentina, 132,000 in Russia, and 117,000 in Australia, while there are only 27,000 Jews in the Arab and Muslim world.

The Theoretical Model

The model we constructed proposes an explanation of the impact of demography on national security and lays the groundwork for further discussion of the possible effect of the mediating variables on demography, which is the independent variable in the model. The dependent variable in the theoretical model is national security, defined as ensuring the long-term existence of a secure and thriving Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people. The independent variable consists of demographic variables divided into two categories: internal variables and external variables (reflecting the four dimensions of demography to which we refer in this article). National security as a dependent variable is influenced by two main factors that we define as mediating variables: national power, which consists of the means and ability to ensure national security, and threats to national security that we have divided into two categories: external threats and internal threats. The demographic variables in both categories influence both mediating variables, while they in turn influence the dependent variable.

In the category of internal variables of the independent variable, we refer to elements such as Jewish-Arab relations in Israel, the religious level of the Israeli Jewish population (secular, traditional, religious and Haredi), the regional demography of the Israeli periphery and center, the demography of the education system, the labor market, the health system and more.

In the category of external variables, we refer to such factors as refugees and displaced persons in the region around Israel, poverty, ignorance versus education, rates of employment, demographic trends within regional populations (fertility, mortality, migration), the demography of minority and majority groups, ethnic and religious groups and more. As stated, the range of variables in both categories mentioned are collected into the four demographic dimensions referred to in this paper in the analysis of the link between demography and national security in the Israeli context.

In referring to the two mediating variables, we have defined national power—referring to the sum of capabilities and resources available to the state to ensure national security—by means of several dimensions that when combined create national capacity as a whole. They include military power, economic power, technological power, political power, social power (in the sense of unity, resilience, shared fate and shared destiny as the sub-components of social power). The mediating variable of threats has been split into two categories: external threats—all those originating outside the borders of sovereign Israel, including the Palestinian threat, and internal threats that originate within the country.

There is an interaction between the two mediating variables, since the various components of national power must inter alia enable a response or the ability to tackle the threats, while some of the threats can influence elements of national power. In this model we have chosen to present these as distinct variables, each of which can stand alone, since we have identified the unique effects of some of the demographic variables on each of them separately and distinctively.

The theoretical model presents the impact of the demographic variables on the mediating variables, and their impact on the dependent variable in a causative and somewhat linear manner. While developing the model we were exposed to the need to develop two additional levels: systematic operationalization of the impact, that is, a definition of metrics to examine the direction and intensity of the effect, and the extent of the feedback loop. In the analysis of the mediating variables we arrived at the recognition that in some cases they could affect the independent variables. For example, military power has an effect on the ability to frustrate and prevent the entry of refugees into state territory, thus repressing or reducing the motivation of migrants to attempt to move to Israel.

Another possibility is the effect of economic power on demographic trends among Israeli Arabs with regard to participation in the labor market, integration into Israeli society, and a decline in fertility as a consequence of modernization and the entry of Arab women into the workforce. In this paper we have tried to focus on the first level of the model as presented below, and not on the possible feedback loop of the impact of the mediating variables on the independent variable—the demography—since the purpose of this article is to illustrate in a general way the influence of demography on national security and provide a preliminary basis for an analytical tool, which can help decision makers and policy-makers to examine issues of national security in terms of demographic influences.

In the presentation of the wide spectrum of demographic variables in two categories, it is also possible to create a hierarchy of variables based on their importance, and it would perhaps be correct to focus attention and analysis on a limited number of critical demographic variables in each of the categories. Through research manipulation of the variables (shrinking and stretching them) it will be possible to examine the whole range of demographic influences on national security. Another option when referring to the demographic variables, mainly the category of internal variables, is to think about variables relating to the relative power of groups in society, their levels of satisfaction with the existing distribution of resources, the strength of any internal rifts, or alternatively their level of unity and solidarity, the quality of the government’s enforcement mechanisms, and so forth, and then to build a model for their impact on national security. Power Transition Theory (PTT) can help to lay the theoretical and practical foundation for this (Organski and Kugler 1980).

Key:

- A solid line represents the first level of the model—the impact of the independent variable on the mediating variables, and their impact on the dependent variable.

- The dotted lines represent the second layer of the model—the feedback loop—the impact of the mediating variables on the independent variable —demography.

Summary

Demography in its various dimensions has enormous impact on national security in general, and in the case of Israel—a country that is strikingly demographically inferior in a challenging and partly hostile environment, in a situation of an entrenched, ongoing dispute with the Palestinians, and under existential threat from Iran—in particular. In this article we have sought to define the interfaces and links, as well as the demographic effects on its national security, with reference to four aspects: internal, between the river and the sea, the regional context and the Diaspora.

We have based the explanations on a theoretical model that presents the effect of the demographic variables in two categories (internal and external) on national security, by means of two mediating variables (national power with its various components, and threats, divided into two categories: internal and external).

We have also referred to some of the articles appearing in this special issue, to draw out the common threads of the various articles dealing with aspects and dimensions of demography and indicate their effect on national security. A deeper understanding of demography and the ability to investigate demographic trends and how they affect national security—these are tantamount to obligatory for decision-makers and policy-formers. Deficient understanding or gaps in perception could damage a state’s ability to secure its national security, to identify dangers and challenges in good time, and to develop suitable responses, but could also interfere with its ability to identify the opportunities which can and must be leveraged to reinforce national security.

Sources

Abrams, Elliott. 2016. “If American Jews and Israel are Drifting Apart, What's the Reason?” Mosaic, April 4, 2016. https://tinyurl.com/2cpafuhe

Abulof, Uriel. 2014. “Deep Securitization and Israel's ‘Demographic Demon.’” International Political Sociology 8(4): 396–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12070

Ben-David, Dan and Ayal Kimchi. 2023. The State of Education in Israel by National and Demographic Comparison. Shoresh: Economic-Social Research Institute. https://tinyurl.com/ycxk5865

CBS. 2022. Press Release—Births and Fertility in Israel, 2020. February 21, 2022. https://tinyurl.com/2p8zasb9

CBS. 2023. Press Release – Population of Israel at the Start of 2024. December 28, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/67yyt263

Coleman, Peter T. 2006. “Intractable Conflict.” In The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice edited by Morton Deutsch, Peter T. Coleman and Eric C. Marcus, 533–559. Wiley Publishing.

Della-Pergola, Sergio. 2024. “The Future of Israeli and Jewish Demography.” Strategic Update (This collection).

Dvir, Noam. 2020. “150,000 Engineers and 43,000 Doctors: The Immigration from the Soviet Union in Numbers.” Israel Today, January 12, 2020. https://tinyurl.com/bdzmt54x

Eichner, Itamar. 2003. “Eve of New Year 5784: The Number of Jews in the Rorld Reaches 15.7 million.” Ynet, February 15, 2003. https://tinyurl.com/mr3j9su4

-. 2024. “Netanyahu in Unusual Response on Saturday to Biden’s remarks: “We will Retain Full Security Control of Gaza.” Ynet, January 20, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/yze6p97e

Ettinger, Yoram. 2006. “Forget the Demographic Threat.” Ynet, February 8, 2006. https://tinyurl.com/3tt5587m

Even Shmuel. 2020. “Demographic Issues in Israel—In the Mirror of National Security and Intelligence.” Intelligence in Practice—Methodological Intelligence Journal: National Civil Intelligence —Approaches and Ideas for Implementation in Israel 5: 178-164. IICC and the Institute for the Study of the Methodology of Intelligence. https://www.intelligence-research.org.il/userfiles/image/cat5/%D7%92%D7%99%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%95%D7%9F%205%20%D7%9E%D7%90%D7%9E%D7%A8%2012.pdf

-. 2021. “The Demography of Israel at the Start of a New Decade: National Significances.” Strategic Update 24(3): 28-41. https://tinyurl.com/2rrpkayy

Georgakis Abbott, Stefanie and Yannis A. Stivachtis. 2019. “Demography, Migration and Security in the Middle East.” In Regional Security in the Middle East: Sectors, Variables and Issues, edited by Bettina Koch and Yannis A. Stivachtis, 99-130. E-International Relations.

Gilboa, Etan. 2020a. “The Contributions of the United States to Israel’s Security.” Strategic Update 23(3): 15-29. https://tinyurl.com/2j6hrpka

Gilboa, Etan. 2020b. “The United States is Changing, and Israel Must Rethink its Relations with the Democrats.” Walla!, October 9, 2020. https://news.walla.co.il/item/3391248

Goerres, Achim and Pieter Vanhuysse. 2021. “Introduction: Political Demography as an Analytical Window on our World.” In Global Political Demography: The Politics of Population Change, edited by Achim Goerres and Pieter Vanhuysse, 1-27. Palgrave Macmillan.

Goldstone, Jack A. 2002. “Population and Security: How Demographic Change can Lead to Violent Conflict.” Journal of International Affairs 56(1): 3-24.

Halamish, Aviva. 2024. “The Interaction Between Demography, Territory and Time in Shaping Zionist and Israeli Policy—1897-1951.” Strategic Update (This collection)

Hartmann, Christoff and Catherine P. Biira. 2021. “Demographic Change and Political Order in Sub-Saharan Africa: How Côte d’Ivoire and Uganda Deal with Youth Bulge and Politicized Migration.” In Global Political Demography: The Politics of Population Change, edited by Achim Goerres and Pieter Vanhuysse, 219-246. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ilan, Shachar. 2019. “Study: In 2065—Half the Children will be Haredim.” Calcalist, November 12, 2019. https://tinyurl.com/5n8udbf6

Kahaner, Li and Gilad Malach. 2023. 2023 Yearbook of Haredi Society in Israel. Israeli Institute for Democracy. https://tinyurl.com/5n7w722a

Karni, Yuval. 2024. “Netanyahu Versus Galant: We’ll Set Objectives for Haredi Recruitment, Absolute Agreement – Only Exists in North Korea.” Ynet, February 29, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/4zex6rz5

Klein, Axel and Hannes Mosler. 2021. “The Oldest Societies in Asia: The Politics of Ageing in South Korea and Japan.” In Global Political Demography: The Politics of Population Change, edited by Achim Goerres and Pieter Vanhuysse, 195-217. Palgrave Macmillan.

Krebs, Ronald R. and Jack Levy. 2001. “Demographic Change and Sources of International Conflict.” In Demography and National Security, edited by Myron Weiner and Sharon Stanton Russell, 62-105. Berghahn Books.

Lasansky, Scott. 2018. “Fate, Peoplehood and Alliances: The Present and Future of Relations Between Jews in the United States and in Israel.” In The American Jewish Community and Israel’s National Security, edited by Assaf Orion & Shachar Eilam, 65-102. The Institute of National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/mrynwszw

Len, Shlomit. 2020. “30 Years After the Large Wave of Immigration From Russia: How Israel Changed Beyond Recognition.” Globes, January 24, 2020. https://tinyurl.com/2s4bdzkm

Leshem, Elazar. 2009. Integration of Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union 1990–2005: A Multidisciplinary Infrastructure Research. Massad Klita, Joint-Israel, Jerusalem.

Lustick, Ian S. 2013. “What Counts is the Counting: Statistical Manipulation as a Solution to Israel’s ‘Demographic Problem.’” Middle East Journal 67(2): 185–205.

Michael, Kobi. 2014. “The Weight of the Demographic Dimension in Israel’s Strategic Considerations in the Israeli-Palestinian Dispute.” Strategic Update, 17(3): 27-38. https://tinyurl.com/4pdhmeu2

Michael, Kobi and Ori Wertman. 2023. “The last ‘Mapainik’ and the ‘Iron Wall’: Benjamin Netanyahu and the Palestinian issue 2009-21.” Israel Affairs, 29(6): 1115-1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2023.2270247

Michael, Kobi and Yoel Gozansky. 2016. The Arab Region on the Track of Political Failure. The Institute of National Security Studies.

Miller, Benjamin. 2024. “Nationalism and Conflict: How do Variations of Nationalism Affect Variations in Domestic and International Conflict? Political Science Quarterly qqaex014. https://doi.org/10.1093/psquar/qqae014

Miller-Katav, Orit. 2024. Proposals Versus Reality: Addressing West Bank Demography in Israel—1967-1977. Strategic Update (this collection).

Milstein, Michael. 2022. It’s a Mystery that Nobody Wants to Investigate: How Many Arabs are There Really Between the Jordan River and the Sea? Haaretz, September 8, 2022. https://tinyurl.com/4ydkda75

Neria, Zack. 2016. Between Rabin and Arafat: Political Diary 1993-1994. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.

News1. 2021. “Defense Minister Benny Gantz on Relations with the USA: ‘Israel Must Conduct a Dialogue with its Partners’” (video). YouTube, December 20, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/3debcjup

Noesselt, Nele. 2021. “Ageing China: The People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan.” In Global Political Demography: The Politics of Population Change, edited by Achim Goerres and Pieter Vanhuysse, 117-140. Palgrave Macmillan.

Orion, Assaf and Shachar Eilam. 2018. “Main insights and Recommendations.” In The American Jewish Community and Israel’s National Security, edited by idem., 23-41. The Institute of National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/mrynwszw

Raved, Achiya. 2018. “Survey: About half Of Israel’s Arabs Do Not Recognize it as the Jewish state.” Ynet, March 7, 2018. https://tinyurl.com/4mw7m8zv

Ravid, Barak. 2011 “Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu: There Must be a Jewish Majority in Israel, Not Between the Jordan River and the Sea.” Haaretz, June 21, 2011.

Rubinstein, Roi and Moran Azulai. 2024. “Galant Threatens: “Without the Whole Coalition’s Agreement – I won’t Submit the Recruitment Law. Everyone Must Share the Burden.” Ynet, February 28, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/4dn82cm3

Sciubba, Jennifer Dabbs. 2012. “Demography and Instability in the Developing World.” Orbis, 56(2): 267-277. DOI:10.1016/j.orbis.2012.01.009

Shalom, Zacki. 2018. “The Crisis in Relations Between Israel and the Jewish Community in the United States: Background and Implications.” In The American Jewish Community and Israel’s National Security, edited by Assaff Orion and Shahar Eilam, 103-142. The Institute of National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/mrynwszw

Shapiro, Daniel. 2018. “Opening Remarks.” In The American Jewish Community and Israel’s National Security, edited by Assaff Orion and Shahar Eilam, 15-18. The Institute of National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/mrynwszw

Siboni, Gabi and Kobi Michael. 2023. Eritrean Violence in the Heart of Tel Aviv. Misgav—Institute for National Security and Zionist Strategy. https://tinyurl.com/5n6a9zk6

Sofer, Arnon. 2006. “This is How the Demographic Penny Dropped for Sharon.” Ynet, January 9, 2006. https://tinyurl.com/52pft5p7

-. 2006b. “The Demographic Demon is Alive and Kicking.” Ynet, February 13, 2006. https://tinyurl.com/yxtpawd7

-. 2006c. The Struggle for Water in the Middle East. Tel Aviv: Am Oved.

Sofer, Arnon and Evengia Bistrov. 2008. The State of Tel Aviv—A Threat to Israel. Haifa: The Chaikin Chair for Geostrategy—Haifa University.

Tal, Yisrael. 1996. National Security—the Few Against the Many. Dvir Publishing.

Tibon, Amir. 2013. “Netanyahu: ‘Preventing a Bi-National State – a Strategic Objective.’” Walla!, July 20, 2013. https://tinyurl.com/2r3nbx66

Toft, Monica Duffy. 2012. “Demography and National Security: The Politics of Population Shifts in Contemporary Israel.” International Area Studies Review, 15(1): 21-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2233865912438161

Tragaki, Alexandra. 2011. “Demography and Security, a Complex Nexus: The Case of the Balkans.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 11(4): 435-450. DOI:10.1080/14683857.2011.632544

Wertman, Ori. 2021. “The Struggle Against the Threat of the Bi-National State: The Oslo Accords 1993-1995 in View of the Theory of Security (Securitization).” Strategic Update 24(4): 18-30. https://tinyurl.com/3hucrfk6

Winkler, On. 2022. Behind the Numbers: Political Demography in Israel (digital). Lamda – The Open University.

-. 2024. “Internally and Externally: The Changing Demographic Threat to Israel.” Strategic Update (This collection).

Yadlin, Amos. 2018. “Preface.” In The American Jewish Community and Israel’s National Security, edited by Assaf Orion and Shachar Eilam, 9-12). The Institute of National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/mrynwszw

-. 2021. “Climate, Environment and National Security—A National Challenge as well as a Research Challenge. In Environment, Climate and National Security: A New Front for Israel. Memorandum 209, edited by Kobi Michael, Alon Tal, Galia Lindenstrauss, Shira Bukchin Peles, Dov Hanin and Victor Weiss, 11-16. The Institute for National Security Studies.

Zamir, Eyal. (2022). The Regional Campaign Against Iran for Control of the Middle East. Washington Institute. https://tinyurl.com/3z4ce88w

Zureik, Elia. 2003. “Demography and Transfer: Israel's Road to Nowhere.” Third World Quarterly, 24(4): 619-630. DOI:10.1080/0143659032000105786