Publications

INSS Insight No. 1542, December 22, 2021

In the past two years, Israel has unofficially renewed the employment of Gaza Strip residents in Israel, and the number of Gazans who received “merchant permits” rose to 10,000 in October. This article briefly reviews the history of employment of Gaza residents in Israel and the connection between this employment, unemployment in the Gaza Strip, and support for Hamas. Based on findings presented here, the article concludes that the effect of employment of 10,000 Gazans in Israel on unemployment in the Gaza Strip is likely to be limited, due to the considerable size of the Palestinian local labor force. In addition, its effect on support for Hamas is unclear.

In late October 2021, Israel announced that it would increase the number of “merchant permits” for the Gaza population from 7,000 to 10,000, with a large proportion of these intended for salaried work in Israel. This step was taken after the number of “merchant permits" from the Gaza Strip rose from 3,000 to 5,000 in July 2019, and from 5,000 to 7,000 in early 2020, before the entry of workers into Israel was banned at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The recent increase in the number of permits was accompanied by expansion of the fishing zone and increased exports from the Gaza Strip to Israel. The aim of these measures was to improve the economic situation of the Gaza population, which has suffered severely in the 16 years since the disengagement in 2005, and whose situation especially deteriorated once Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip. The Israeli government and the security forces hope that a better economic situation in Gaza will help maintain the security lull on Israel's southern border, as Israel could threaten to easily reverse this policy if the calm in the area is upset. Furthermore, should this happen, the Gaza Strip residents working in Israel, their families, and others benefiting directly or indirectly from employment in Israel are presumably likely to accuse Hamas of harming them economically through security escalation.

An increased number of permits is known to have significant effects, above all for the families receiving one of the permits. The average daily wage in the Gaza Strip in the second quarter of 2021 was NIS 60, and the wage in the private sector there was only NIS 32. The weak demand for workers is also reflected in the high unemployment rate (48 percent), along with a low employment to population ratio of 21 percent among those aged 15 and up. For the sake of comparison, the unemployment rate among Palestinians on the West Bank was 17 percent, while the employment to population ratio was 37 percent. In other words, only one out of five Gaza Strip residents over 15 is employed, while only one out of three Palestinian residents of the West Bank is employed.

In this dismal state of affairs, and in a labor market that is so difficult for workers, a work permit in Israel is a significant event for the workers and their families. This is the case even if they do not earn as much as the Palestinian workers from the West Bank, who are paid a daily average wage of NIS 265.

Work Permits for Workers from Gaza over Time and a Current Picture

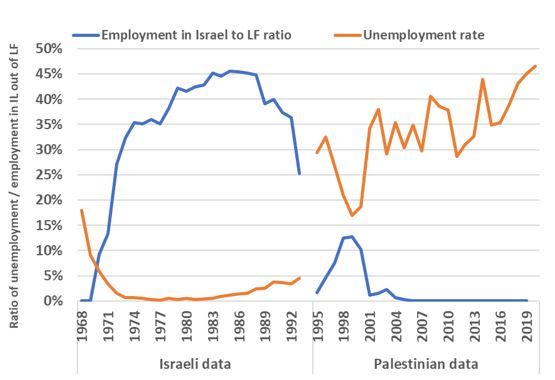

The increase in the number of entry permits for Gazans over the past two years constitutes another sharp reversal in Israeli policy. Figure 1 displays the employment in Israel to labor force ratio and the unemployment rate in the Gaza Strip labor force from 1968 to 2019. In the 1970s and 1980s, Israel encouraged Gazans to work in Israel, with the number of those employed there reaching a peak of 46,000 in 1987. In 1991, following the Gulf War, Israel built a fence around the Gaza Strip, and began controlling the movement of workers to Israel. The number of Gazans working in Israel fell to 38,000 in 1991-1993, and to a few thousand in 1995-1996. Israel expanded employment of Gaza Strip residents to 26,000 in 2000 (before the second intifada), reduced it again when the violence began, and halted it completely with the disengagement, before renewing it unofficially in 2019.

Figure 1: The Employment in Israel to Labor Force Ratio and the Unemployment Rate in the Gaza Labor Force | Sources: 1968-1993: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics; 1995-2020: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

Increased employment in itself did not prevent violent escalation in either the first or second intifada. Furthermore, Figure 1 highlights the negative correlation between the proportion of the Gaza labor force working in Israel and the unemployment rate in Gaza itself: the Israeli data show that the unemployment prevailing in the Gaza Strip in the late 1960s fell with the expansion of employment in Israel, and rose in the mid-1980s. At the same time, according to the Palestinian data, the correlation between the two series is stronger in the 1990s and the early 2000s. An increase of 1 percent in the proportion of Gaza’s labor force employed in Israel was accompanied by a 1.2 percent decrease in the unemployment rate in Gaza. The effect on employment in the Gaza Strip under Hamas rule – following a decade and a half of economic restrictions and armed conflict, which depressed the Gaza Strip economy – will likely be lower, because the multiplier effect will be smaller.

Accordingly, a hypothetical increase to 10,000 of Gazans employed in Israel, amounting to 2.1 percent of the Gaza Strip labor force, which currently consists of 474,000 workers, is likely to reduce unemployment from 47 to about 44 percent. A significant reduction in the unemployment rate in the Gaza Strip by means of employment in Israel, say by 10 percent to 37 percent, will require issuing permits to 43,000 workers. A complete lowering of unemployment by a hypothetical return to an equilibrium with free movement between the Gaza Strip and Israel, which was the situation on the eve of the first intifada, is likely to flood the Israeli labor market with one third of the Gaza Strip labor force – over 150,000 workers lacking skills relevant to the Israeli labor market. Such a return to this equilibrium will be of great benefit to the Hamas regime, which could claim that its violent campaigns were responsible for a significant improvement in Gaza’s economic situation. However, it is not at all clear that this equilibrium is good for the Israeli economy, even aside from security risks, because Gaza workers are liable to push uneducated workers, particularly from the Arab sector, out of the labor market.

Implications of the Increase in Work Permits for the Gaza Strip

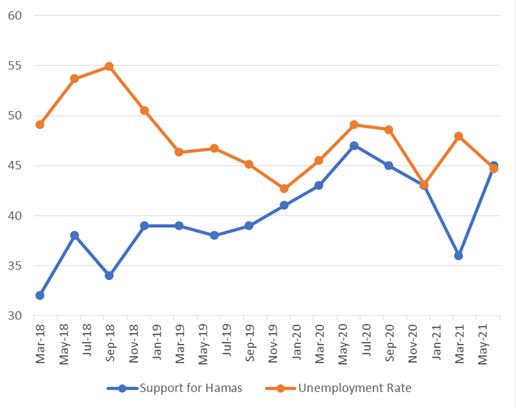

Although Israel is hoping that the new policy will increase the internal pressure on Hamas to refrain from violent attacks against Israel, realization of this desire is highly dubious. First of all, it is by no means clear that there is a significant connection between the unemployment rate and support for Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Intuitively, a higher unemployment rate should be correlated with a decrease in public support for Hamas.

Figure 2: The Unemployment Rate and Support for Hamas in the Gaza Strip | Sources: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics and Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research

In actuality, however, the picture is more complicated. Figure 2 shows that this connection existed in 2018-2019, when a 1 percent decline in the unemployment rate was accompanied by a 0.5 percent rise in public support for Hamas. In 2020, on the other hand, there was an opposite correlation between unemployment and support for Hamas, with the two series moving in the same direction. We suggest that this trend was affected by the pandemic, which caused an increase in unemployment, while at the same time, the population had to rely to a great extent on public services (especially health services) provided by Hamas. In 2021, the correlation between the unemployment rate and support for Hamas again was negative, but it is premature to state on the basis of these two observations whether the correlation will remain negative in the long term.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Increasing the number of work permits for Gazans constitutes a return, and even an expansion, of the relaxation of restrictions by Israel in the area since Operation Guardian of the Walls in May 2021. Theoretically, this policy is welcome, because it is designed to benefit Gazans who are granted work permits, contribute to reconstruction in the Gaza Strip, and help maintain the lull in southern Israel through new economic deterrence. Making security escalation costly is designed to restrain Hamas. In practice, however, increasing the number of work permits to 10,000 will have a minimal effect, if any, on the Gaza Strip economy, and will have a limited effect on preservation of tranquility in southern Israel. The unemployment rate in the Gaza Strip is so high that employing 10,000 workers from there will only lower the unemployment rate to 44 percent. Furthermore, there does not appear to be a direct connection between the unemployment rate and support for Hamas or restraint in violence on Israel.

Beyond these conclusions, it is important to note that the renewed employment of Gaza Strip residents in Israel in part occurs unofficially through "merchant permits," some of which are actually being used to enable workers to enter. This policy is different from the regime of work licenses for Palestinians from the West Bank to work in Israel, which is under the supervision of the Population and Immigration Authority. This system requires compliance with the labor laws in Israel – including provisions for national insurance, pension, and health insurance, and salary slips. This compliance is legally required in order to equalize the cost to the employer of employing a Palestinian and an Israeli worker for the same salary. The aim is to safeguard the rights of the Palestinian workers and restrict the displacement of Israeli workers, especially uneducated workers from the Arab sector. Alternatively, if the workers from the Gaza Strip replace foreign workers, the damage to Israeli society and the Israeli economy will be limited, except for the risk incurred through the absence of continuity in the entry of workers from the Gaza Strip caused by dependence on the security situation. Furthermore, providing "merchant permits" to Gaza residents who are actually working in Israel is liable to expand unreported illegal economic activity in Israel in breach of the government's economic policy.

Regulating employment of Gaza residents in Israel, in particular deducting payments for social benefits, will not only attend to workers' rights, but will also narrow the gap between wages in the Gaza Strip and those in Israel, which is liable to serve as a basis for tax collection by Hamas or the extortion of payments by other parties, as in the West Bank. Because of the extremely low wages in the Gaza Strip, taxing these workers is worthy of consideration – in coordination with the Palestinian Authority – with the revenues being used to finance public goods for the Gaza Strip, e.g., health services, thereby cutting back on the tax base for Hamas.