Publications

INSS Insight No. 1507, August 9, 2021

In early July 2021, the UN Security Council approved the extension of activity at the Bab al-Hawa border crossing for another year. Bab al-Hawa is the sole remaining crossing for the transfer of humanitarian aid to the Idlib region, which is not under the control of the Assad regime. Russia’s rare consent to extend the activity at the crossing could be evidence of its now being willing to cooperate with the Biden administration. Israel should take advantage of the international attention (albeit limited) on aid to Syria and the first signs of American-Russian dialogue on the subject, to establish mechanisms for humanitarian aid to southern Syria, which has become something of a violence-ridden no-man’s land and is above all a target for Iranian influence.

In July 2021, the UN Mandate to operate the border crossing for conveying humanitarian aid to the Idlib region, which is controlled by the rebels in northern Syria and not by the central regime in Damascus, was extended for another year (after six months an activity report will be submitted for an additional six-month extension). Some 3.4 million Syrians live in the area, mostly in refugee camps, in conditions of hunger and dire poverty. Since the border crossing began operation in 2014, it has been the main lifeline for humanitarian aid for the local population and displaced persons. Each month more than 1,000 trucks containing food and medicine for the needy millions cross the border at Bab al-Hawa.

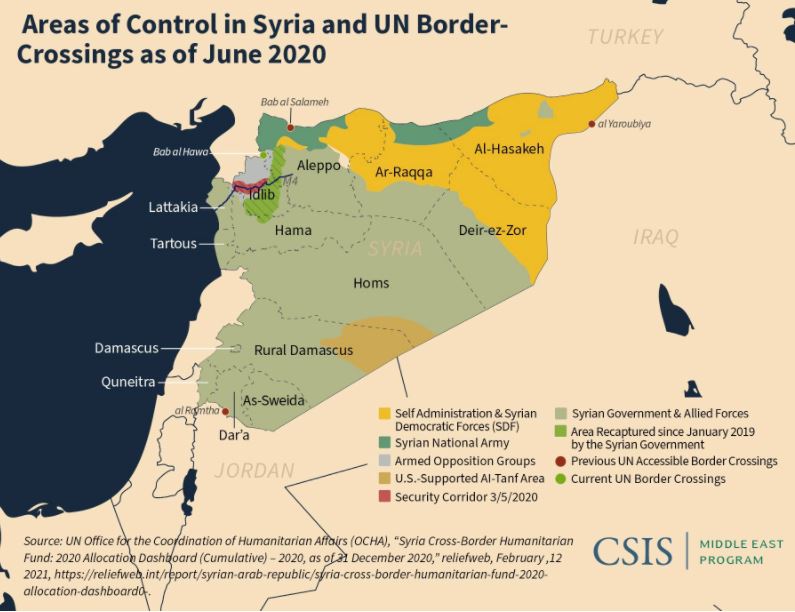

Between 2014 and 2020, UN Security Council Resolution 2533 approved the operation of four humanitarian border crossings into areas outside the control of the Syrian regime: on the borders with Turkey and Iraq – to areas controlled by the Kurds and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and on the Jordanian border – to southern Syria and particularly the Daraa region. In 2020 Russia and China vetoed the operation of three out of the four crossings, claiming that they impinged on the sovereignty of the central Syrian government, thus effectively leaving Bab al-Hawa as the only functioning crossing for humanitarian aid.

Any global attention still directed at Syria is now focused on the Idlib region, which is controlled by the jihadist organization Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, while other areas of the country that still need humanitarian aid, particularly in the south, are ignored. Bashar al-Assad, who controls only about two thirds of Syria’s territory, has taken steps to create the appearance of a functioning government in order to achieve legitimacy and recognition, and to encourage investment in the country. But in fact, Syria is divided into a number of areas of control. The central government lacks the ability to impose its rule and provide the population with basic goods and public services on a regular basis. Apart from the regime’s limited control, the fragile governance is above all a function of the severe economic crisis besetting Syria since 2019.

Despite the lull in fighting compared to previous years, the economic situation has grown worse: more than 90 percent of the population live below the poverty line, including those in areas ruled by Assad. Out of a population of about 17 million, some 13.4 million need humanitarian aid – an increase of 21 percent over 2020. Meanwhile the Syrian pound is at an unprecedented low nadir, having lost 78 percent of its value since October 2019. Prices of basic products have risen by over 250 percent, and electricity is only available for two to four hours a day. In addition, in July the regime raised the prices of fuel, bread, rice, and sugar, which were already in short supply. The COVID-19 pandemic only made the humanitarian crisis worse – about half the medical institutions in Syria function only partially or not at all. And finally, according to a UN report, over the last two years living standards, and the ability to obtain basic necessities, have declined among 82 percent of Syrian households.

Idlib is the most problematic region in humanitarian terms due to the influx of refugees and displaced persons, but the harsh reality has not bypassed other regions under the regime’s control, particularly in southern Syria. In addition to the economic crisis, the south is experiencing violent clashes and instability, partly because of economic pressures, the absence of governance, and contesting loyalties. For example, in late July fighting broke out in the southern region of Daraa, when the Assad regime tried to take control by means of military force, in order to establish its rule and abolish the local powers that were granted to the Central Committee of Daraa in the framework of the 2018 reconciliation agreements signed under Russian auspices.

Southern Syria has become a chaotic area, with a multitude of armed factions engaged in fighting each other and the regime’s forces – including opposition groups, elements under the influence of Iran or Russia, and local elements that enjoy some degree of autonomy from the central government. The regime occasionally imposes a blockade on particular areas, such as Daraa, compounding the widespread hunger and poverty and exacerbating the existing humanitarian crisis. Iran and its proxies are exploiting the frail government and the economic crisis in this area, as they seek to establish their influence. As described by a local Syrian: “Those who lived here have died or fled. The locals who remain are armed, with deep political awareness and only committed to themselves. Today there is no economic security or any security, and a lot of chaos. There’s a black hole here, which sucks in [Iranian] influence.”

Humanitarian Aid: From an International Bone of Contention to an Opportunity – also for Israel

Israel should address the humanitarian issue because of its shared border with Syria. The recent international discussion about extending humanitarian activity at Bab al-Hawa creates a temporary window of opportunity for this purpose.

The fact that Syria is currently divided into areas of influence embodies potential benefits for Israel that can be realized by adopting a differential policy, adjusted to different areas of the country. In the south, Israel’s interest is to influence development on the Syrian Golan Heights in order to prevent the entrenchment of Iranian proxies and to limit the security threat posed to Israel. Apart from the effectiveness of military attacks against Iranian targets in Syria, Israel can expand its range of activity by communicating (directly or indirectly) with local communities that oppose the Assad regime and Iranian influence, particularly Sunni elements and the Druze who are eager for dialogue and support from Israel. Ties with local communities can be reinforced with humanitarian aid – food, fuel, healthcare. This move will strengthen Israel’s influence in the area, and above all reduce the locals’ dependence on Hezbollah and Iran, which are keen to exploit their distress. In other words, in the case of complicated and entangled conflict arena, where the other side is using military, economic, and civilian efforts to wield an advantage, Israel should also make use of a variety of tools – military and civilian – to avoid abandoning the area to Iran and its proxies. Such a move may eventually become the foundation for regional cooperation, perhaps even enlisting other Arab countries, particularly the Gulf states, to provide investment and economic aid for the region’s recovery, and as a substitute for the Iranian presence.

At the international level, the Biden administration has positioned the humanitarian issue at the top of its political agenda in Syria. Moreover, the administration hopes to use this issue to test Russian willingness to compromise and cooperate on other issues. In its view, Russian willingness to extend aid could be the first step toward renewal and expansion of bilateral processes in Syria, along with other constructive measures.

Toward a New Approach

The war in Syria has lasted over a decade, and continues to create security challenges, humanitarian crises, and instability that spills over into the international arena, and no relevant party appears able to stop the deterioration. Targeted moves, such as humanitarian aid to local populations, could be the first step toward local and regional cooperation, and even a springboard for broader international dialogue (now that Russia has softened its stance on the subject) about Syria’s future under the outline of UN Security Council Resolution 2254 (a roadmap to a Syrian settlement, December 2015). Such cooperation could be effective in stabilizing the area, and also help to achieve Israel’s security interests.

Russia is a primary actor in Syria in general and southern Syria in particular, and therefore any humanitarian aid to the local population must be coordinated with Moscow (with American knowledge). Although Russia has so far objected to any humanitarian efforts that bypass the Assad regime, it is possible that such aid might now serve Russian objectives: restoring stability and calming the fighting in the south; limiting the Iranian presence and influence in the south; restoring Russia’s image as a responsible actor that is also active on the humanitarian front. Moreover, involvement on aid could give Russia credit with Washington and widen the scope for cooperation between the powers, perhaps even on matters that go beyond the Syrian arena. In return, Russia would probably ask Israel to stop or at least limit its attacks on targets linked to the Assad regime, and for the aid to be sent under the auspices of humanitarian organizations, without Israeli fingerprints. For that purpose, it would be necessary to recruit Jordan, which also has interests in the area – reduction of smuggling, removal of Iranian influence, and stabilization. If an aid corridor from Israel through Jordan can be achieved, it will increase the chances of gaining Russian consent and recruiting other international elements toward this effort.