Publications

INSS Insight No. 844, August 14, 2016

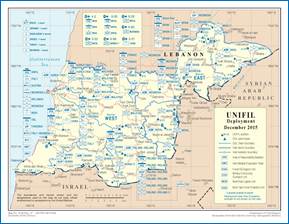

UN Security Council Resolution 1701 of August 11, 2006 ended the Second Lebanon War and outlined the security regime that has been in effect for the past decade between Israel and its northern neighbor. To support the Lebanese government in fulfilling the resolution, UNIFIL, the temporary UN force in Lebanon (first established in 1978 by UN Security Council Resolution 425 following the IDF’s Operation Litani), was expanded from 2,000 soldiers before the 2006 war to 12,000 troops of higher quality. In the decade since its reestablishment, UNIFIL II helped stabilize the post-war situation, and maintain the calm between Israel and Lebanon, reflecting the international community’s ongoing commitment to stability in this sector. At the same time, UNIFIL’s operations – as well as its inactions and passivity – demonstrate the limits of multinational UN forces entrusted with a disputed mission and authorized by a limited and limiting mandate in a mixed state/non-state environment that is a twilight zone as far as sovereignty is concerned. The critical influence of political considerations on operational reality on the ground is likewise readily apparent.

Resolution 1701 sought to end the fighting between Israel and Hezbollah and correct the conditions that led to the war, i.e., armed forces in Lebanon that are not subordinate to the national government, deployed in southern Lebanon along the Israeli border, arm themselves freely and act at will. The resolution called on the Lebanese government to exercise its full sovereignty over all of its national territory, deploy the Lebanese army south of the Litani River, and ensure “the establishment between the Blue Line and the Litani river of an area free of any armed personnel, assets and weapons, other than those of the Government of Lebanon and of UNIFIL.”

In the months following the war, UNIFIL built up its forces, including with significant numbers of quality troops from Western Europe, and helped coordinate the IDF’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon and the Lebanese army’s deployment in the area. Later, it worked hard to rebuild civilian infrastructures, clear out unexploded ordnance, and restore life to normal. At the same time, the UNIFIL Maritime Task Force (MTF) embarked on its mission of monitoring the shipping routes to Lebanon, while the ground forces patrolled southern Lebanon extensively and located Hezbollah military infrastructures used by the organization in the war.

UNIFIL’s successes in its reinforced format (UNIFIL II) lie primarily in stabilizing the security situation in southern Lebanon and preventing another large scale escalation between Israel and Hezbollah. While the core of the unprecedented calm lies in the fundamental and common lack of desire for another war between Israel and Hezbollah, as well as their mutual deterrence and their restrained conduct, UNIFIL’s contribution has been in dousing and containing tactical events of friction before they develop into outright security incidents and widespread fighting. This achievement is in no small part due to UNIFIL’s ability to regulate the civilian/security border area activity between the two sides, whereby shepherds, farmers, eccentrics, herds of animals, Israeli and Lebanese soldiers, and Hezbollah fighters dressed in civilian garb all share adjacent and sometimes overlapping areas, in the absence of a mutually accepted border and visibly clear demarcation line. In this regard, a key function is filled by an ongoing tripartite liaison mechanism between UNIFIL, the IDF, and the Lebanese army, in real time operational communications and in monthly meetings among military working teams taking place at the UN base in Naqoura, and by coordinated activity to mark the Blue Line in the area and resolve routine and infrastructure problems. This mechanism, which provides military commanders with a complementary, non-kinetic tool, has been critical in preventing escalation, reducing the risk of renewed flare-ups, resolving disagreements, transmitting messages, and formulating creative solutions for maintaining the calm. This important UNIFIL contribution to reality on the ground is also useful politically, as the situation in Lebanon has thus remained on the agenda of the Security Council and key contributing nations, which are in constant contact with Israel on the topic.

Alongside its successes, however, UNIFIL has failed to a degree to prevent attacks from Lebanon aimed at Israel and to keep this area free of hostile activity. Since the end of the war, more than 20 incidents of rocket fire from Lebanon to Israel have been recorded, most apparently by organizations other than Hezbollah, while others were prevented thanks to UNIFIL and Lebanese army action and foiled before launch. In this period, there were several exchanges of fire between Lebanese Armed Forces and the IDF, including incidents that resulted in deaths on both sides. In recent years in particular, several Hezbollah attacks from Lebanese soil were aimed at the IDF, including explosive devices in the Mt. Dov sector and anti-tank guided missiles fire, which in January 2015 killed two IDF soldiers. (In that incident, a Spanish UNIFIL member was killed by IDF return fire.) While UNIFIL participated in the efforts to contain these incidents and prevent escalation, it failed to prevent them from occurring in the first place and also failed to prevent the basic conditions that made them possible, even when specifically warned in advance.

This lack of success relates to UNIFIL’s major failure regarding Resolution 1701, i.e., failure to address the Hezbollah arms issue. Since the end of the war, not only has nothing been done toward a situation in which UNIFIL’s Area of Responsibility south of the Litani is “free of any armed personnel, assets and weapons, other than those of the Government of Lebanon and of UNIFIL,” but Hezbollah has beefed up, broadened, deepened, and increased its military deployment in southern Lebanon and elsewhere in the country. The roots of the failure lie in the flimsy foundations of Resolution 1701. As an international institution with the state as its basic building block, the UN Security Council called on the government of Lebanon, in response to its request, to exercise its sovereignty on every part of its soil and, through its army, demilitarize southern Lebanon and dismantle armed militias, including Hezbollah. UNIFIL was charged with helping the government of Lebanon achieve this as per Lebanon’s request and to the best of its ability in the context of Chapter VI of the United Nations Charter (“Pacific Settlement of Disputes”) rather than Chapter VII of that document (“Action with Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression”). In practice, Lebanon is a weak state whose government, to the extent that it functioned at all during this period, was being held hostage by Hezbollah, which is part of that same government. The Lebanese army too is Hezbollah’s hostage and sometime partner: Hezbollah is militarily stronger, and politically paralyzes the state’s military. Thus, regarding the military dimension, Resolution 1701 was emptied of any real content even when it was formulated, and dynamics on the ground continued to deny it substance.

Among the tens of thousands of ships that have undergone “monitoring” by the MTF over the last decade, only one weapons shipment, en route to the Syrian rebels, is remembered as actually apprehended. The entrance of all other shipments to Lebanese ports was approved by the government. As for land operations, to Hezbollah’s displeasure, certain UN forces became known early on for being particularly assertive and mission-motivated while on patrol. In the summer of 2007, however, six soldiers of the Spanish battalion were killed by a vehicle borne explosive device near the Shiite village of al-Khiyam. Over the years, many UNIFIL patrols have been attacked by so-called “angry citizens” – usually young men, sometimes armed, many equipped with tactical radio communications. UN soldiers have been bruised and brutalized and have had much equipment “confiscated,” including cameras, navigation, electronic and communication devices. Hezbollah personnel have routinely been identified on regular patrols along the Blue Line barrier, while Hezbollah’s military areas have been practically declared off-limits on the pretext of being “private.”

Under the increased pressure, UNIFIL forces gradually scaled back their determination and desire for effective monitoring. In several instances in which Hezbollah ammunition stored in civilian buildings exploded, UNIFIL was denied access by Hezbollah and the Lebanese army until all the evidence was removed and the scene sterilized. UN reports about such incidents have been couched in very circumspect legalese, noting the lack of clear evidence of violations of Resolution 1701, especially under the pressure of the Lebanese government as the host “state,” and under explicit or implied threats on the part of Hezbollah. For example, UNIFIL received European UAVs to assist in its mission in Lebanon, but under Hezbollah pressure these were sent back unopened. In this situation, the IDF has excellent partners who view reality the same way as long as they wear their national hats, but once they don their blue UN berets they are forced to tread very lightly and walk a fine line while navigating between professional integrity, national policies, the safety of their forces, and UN directives.

Ten years of UNIFIL II activity require a sober, balanced view. On the plus side, the force has helped stabilize security and keep the calm, aided in preventing tactical incidents from becoming full-blown escalations, assisted in calming the civilian routines on both sides of the border, helped clarify a border by marking the Blue Line on the ground, created communications and dialogue mechanisms between Israel and Lebanon via their respective militaries, kept an international spotlight on Israel’s strategic environment, and laid an important professional foundation for the legitimacy of Israel’s policy, now and for the future. On the minus side, UNIFIL failed to fulfill its major mission – perhaps inherently a “mission impossible: to support the Lebanese government and army in executing a move they had no intention of performing, namely disarming southern Lebanon, which in practice would have meant disarming Hezbollah. Given the range of political considerations on the parts of the states involved and UNIFIL itself, and in light of the natural and justified concerns about the forces’ safety, UN reports about Lebanon are replete with lacunae and obvious biases, as will become clear on a day of reckoning.

Against this background, several insights emerge for the future. Political achievements coming on the heels of a war and manifested in international resolutions bear much moral, political, and ethical value, but their practical worth depends on the power of their implementation mechanisms. The quality of enforcement depends on the intensity of the sides’ interests and their willingness to take risks and pay the commensurate price. In most cases affecting Israel, one cannot assume that other nations will have as strong an interest in enforcing effective security arrangements; in any event, it is better for Israel that other nations do shed their soldiers’ blood in its defense.

A high quality international force can help stabilize a post-combat situation, recruit international resources, promote channels of communication between the sides, and reduce and contain operational friction. But the need to undertake enforcement operations against the wishes of significant powerbrokers on the ground enjoying military, political, and state power, and without the support of the host nation, puts the UN and its participating nations in a grave quandary as they must consider the safety of their forces, and limits both the quality of performance on the ground and the picture of reality reflected in official reports. Therefore, key conditions for success are a balance of power, which allows for the honest support and effectiveness of the host nations, and a mandate and force adapted to the nature and environment of the task at hand.

As long as Israel fights non-state entities and regulates the end of the fighting with state or international entities, the balance of power on the ground remains no less important than the exact formulation of the documents that seek to end exchanges of fire. Therefore, in a future war, Israel would be wise to avoid extending the fighting for the sake of attaining a better formulation in the mechanism that brings the confrontation to a close and regulates its aftermath, and instead direct the brunt of its efforts on affecting the future threat potential and power balance that will make an improved security regime possible later on.

Based likewise on experience with other UN peacekeeping forces, one can understand Israel’s basic reservations about international enforcement units and also, at times, of inspection forces, when it comes to activity in areas critical to Israel’s existence and the complex environment, e.g., in the Palestinian context. In the Lebanese context, both political and moral logic require that the international community continue to demand that the Lebanese government realize its commitment to Security Council resolutions and not turn its persistent weakness into a universal exemption from responsibility.