Strategic Assessment

Introduction

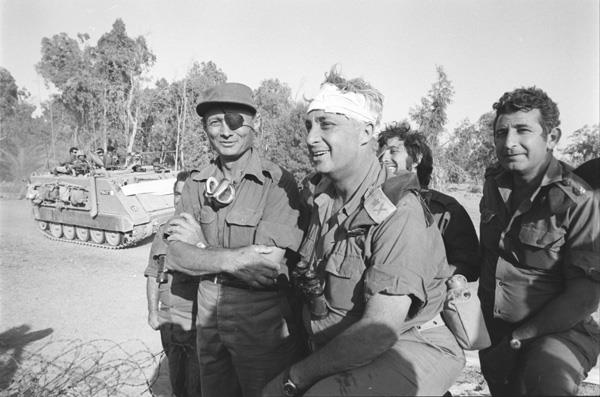

October 23, 1973 marked the end of the Yom Kippur War, a war described by then-Defense Minister Moshe Dayan as one of long bitter days, and rife with blood (Kan Hadashot, 2019; Prime Minister’s Office, 1973). As soon as the war broke out, all parties agreed to stop campaigning for the elections scheduled for October 30, 1973 (Davar, 1973). A short time after the ceasefire came into effect, a “war of generals” began to heat up, arousing intense emotions and mutual accusations that exceeded anything Israel had previously witnessed. The main parties in this “war,” which was conducted primarily in the media and in various government bodies, were Generals Ariel (Arik) Sharon and Shmuel Gonen (Gorodish), and Chiefs of Staff Haim Bar-Lev and David Elazar.

Naturally, the campaign spilled over into the political arena, pulling in the entire national leadership. In the background was the post-war growing public protest, which demanded that all those responsible for the war’s failures accept responsibility for their actions and omissions, draw the necessary conclusions, and vacate their positions in favor of new leaders who were untainted by the Yom Kippur War failures (Lahav, 1999, p. 315). One part of these emotional confrontations was documented at the government meeting of January 27, 1974. This article focuses on the main issues that were discussed at that meeting.

The "War of the Generals": Initial Stages

On November 13, 1973, Maj. Gen. Shmuel Gonen, who at the outbreak of the war served as the GOC of the Southern Command—until Lt. Gen. Haim Bar-Lev was appointed commander of the southern front on October 10, 1973—sent a letter to the Chief of Staff entitled, “The conduct in battle of Maj. Gen. Sharon [who commanded a division in the Southern Command].” “In the course of the war,” Gonen wrote, “I contacted you twice demanding that Gen. Sharon be removed—once on October 9, ‘73 after the failed attack against the invading Egyptian troops” carried out by the Sharon Division. The attack, Gonen stressed, was executed contrary to his explicit order. In this attack, the IDF lost about twenty tanks, some of which were left in enemy territory with members of their crew. “The second time was after the battle over the Egyptian bridgehead over the Suez Canal….Now that the ceasefire [that ended the war] appears to be holding, I feel it is right to demand that you order an investigation of Gen. Sharon’s conduct, and if my allegations are proven correct—that he be put on trial.” Gonen charged that Sharon’s failure to execute the missions he was ordered to carry out during the war was overwhelmingly harmful to IDF discipline and values (Buhbut, 2015; Bergman & Meltzer, 2004, p. 139).

Aware of the stormy wave of attacks he was about to face by his critics, Sharon chose to defend himself in a way familiar to him from his military experience—with strong offense against his attackers. Buoyed by waves of broad public sympathy and severe criticism of the IDF leadership, Sharon's strategy proved highly effective. It succeeded in achieving his objective: his critics came under attack and were forced repeatedly to defend themselves and explain their moves and decisions during the war. In their distress, Sharon’s critics were obliged to grasp at legal and disciplinary straws, hoping to undermine Sharon’s prestige and status. It appears this course of action did not serve their purposes (Agres, 1974).

In mid-November 1973, Sharon gave interviews to leading international newspapers: the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Guardian. These interviews were fraught with Sharon’s blatant criticism of the army leadership under Chief of Staff David Elazar and his predecessor Haim Bar-Lev, and their conduct—before and during the war. He alleged that they failed to prepare the IDF for war, misread the situation at the outset of the war, misconstrued the intentions of the Egyptians, and were unaware of the importance of the time dimension in war. His overriding message, relayed in the headlines of leading newspapers was clear: because of these failures Israel missed the opportunity to gain an absolute victory in the Yom Kippur War (Bar Yosef, 2013; Barnea, 1973; Dan, 1974a; Kipnis, 2016; Shemesh & Drori, 2008).

In the aftermath of these interviews, Chief of Staff Elazar issued a statement in which he tried to undermine Sharon’s credibility and present him as someone who does not act according to the IDF values of comradeship and brotherhood in arms. However, at a time of growing public protest against the security establishment, these values were far less urgent. Thus, his statement most likely appeared as an attempt to prevent the exposure of the failures and the personal responsibility of the Chief of Staff and other senior officers. It is doubtful whether this move could strengthen the Chief of Staff’s status at that difficult time: “It is natural,” Elazar stated, “that issues relating to the war and its conduct should be discussed in public. But unfortunately, biased descriptions and interviews have recently been published [by Sharon] that achieved no positive purpose apart from personal glory, even at the cost of continual attacks on comrades in arms.” The Minister of Defense and the Chief of Staff also issued an instruction to generals to refrain from giving media interviews that deviated from army procedures (Erez, 1973).

On January 20, 1974, Maj. Gen. (res.) Ariel Sharon published an order of the day relating to the end of his service as a divisional commander in the Yom Kippur War. In this order, Sharon praised the role he and his division played in the efforts to block the Egyptian army and prevent it from crossing the Suez Canal, while denigrating the top army command. “Our division,” stated Sharon, “was stationed in an area facing the center of the enemy’s efforts. With heroic fighting and supreme efforts by each one of you, we blocked the Egyptian forces. It was our division that initiated and executed the crossing of the Canal, a move that led to a turning point in the war….In spite of oversights and errors, in spite of failures and stumbling blocks, in spite of a loss of common sense and control [by other commanders in the General Staff], we managed to achieve victory” (Bloom & Hefez, 2005, pp. 288-289). In response, the Chief of Staff reported the Minister of Defense that “yesterday Arik Sharon asked me to release him from special reserve duty. I told him that he could leave….[Also] I intend to notify General Sharon that his appointment as commander of Division 143 is revoked” (Elazar, 1973; Kan Hadashot, 2019). The Minister approved this decision.

The response of the military establishment did not deter Sharon from continuing his attacks on the performance of the General Staff in the war. On January 25, 1974, he gave interviews to Maariv and Yediot Ahronot. In the interviews, Sharon claimed that for several years the IDF was in a severe state of stagnation, and in need of a serious shake-up. The IDF, he claimed, had lost its main weapon—creative thinking, which once made it one of the most venerated armies in the world. Only he, Arik Sharon, knew how to remedy the situation, but in the current political situation there was no chance of agreement on his appointment as chief of staff. We went through a difficult war, said Sharon, and while achieving victory, we were badly hurt. Our leaders, however, learned nothing from this experience, and were still operating on the basis of self-minded considerations (Bashan, 1974; Goldstein, 1974; Kan Archive, 2018).

Sharon alleged that IDF commanders at the highest level failed to understand the situation when the war broke out. Opposing the massive Egyptian force that crossed the Canal demanded a concentration of meta-divisional forces to prevent the consolidation of the Egyptian bridgehead in the first days of the war: “Our plan,” said Sharon to the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, “was to level an immediate counter-blow [with as great force as we had]….This plan [would not mean] that the Egyptians would not reach the Canal or that they would not have a foothold [on our side], but they would not achieve deep penetration….In my eyes, the fact that within one or two days the Egyptians had managed to move an entire array west of the Canal and capture a strip 8-12 km wide, that was something the Egyptians never dreamed of achieving” (Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, 1973). Moshe Dayan wrote: “Based on the Chief of Staff’s plans, the Air Force was charged with the main task at the holding stage….In retrospect, our expectations from the Air Force were proven unrealistic” (Dayan, 1982).

According to Sharon, the IDF command did not understand that the goal of the Egyptian army was not to reach Tel Aviv but to create a bridgehead nearby the Canal (Bergman & Meltzer, 2004, p. 467; TAUVOD, 2013). Therefore, in Sharon’s opinion, all forces should have been focused on destroying the Egyptian bridgehead in the early stages after the Canal was crossed. Furthermore, Sharon claimed that the General Staff commanders did not take the importance of the time dimension into account, which resulted in an increasing erosion of manpower and equipment. At the same time, the world powers began to lose patience as the campaign dragged on, and worked intensively to limit Israel’s freedom of action: “One day before the ceasefire agreement came into force,” Sharon said to the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, “Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Allon visited [the division]. I spoke to him about the time element. I said that we were ignoring the time dimension. He said to me: ‘You can rely on me. This time there’s no time restriction.’ The next day there was a ceasefire” (Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, 1973).

Sharon alleged that Chief of Staff Elazar bore most of the responsibility for the failures of the war, and not the Minister of Defense, and should have resigned as soon as war broke out, or at least when the ceasefire was drawn up. Sharon, who was very familiar with Dayan’s vast military knowledge and experience, did not give reasons that would justify his distinction between the political and the military echelons regarding the responsibility for the failures of the war. He simply stated that Minister of Defense Dayan “should continue to serve in this position in the next government. He is a very brave man, original in his thinking, and worth ten times more than any other candidate for the job” (Goldstein, 1974). It is impossible to avoid the impression that this distinction was also linked to the fact that at that time Sharon was thoroughly involved in political activity, and perhaps saw Dayan and his supporters as political allies to bring down the Mapai government.

“The conflict between the generals,” wrote Uri Dan “[in essence reflected] the conflict between two schools of thought: the schematic concept of massive war of armor against armor, represented among others by Bar-Lev, against Sharon’s approach of special daring operations carried out by small units intended to strike the enemy with a lethal blow”

According to Sharon, relations between IDF commanders had never been as ugly as during that war. In his view, the person responsible for introducing politics into the campaign was former Chief of Staff Bar-Lev. In the years prior to the war, Sharon claimed, senior officers in the IDF were appointed to high ranking positions on the basis of political considerations rather than personal qualifications. He argued that top commanders treated him with hostility accompanied by envy and jealousy as soon as he assumed his position. When the fighting began, Sharon said, he asked them not to obstruct him, and to allow him to conduct the campaign on the basis of his professional knowledge and combat experience. But they, according to Sharon, acted systematically to frustrate him. Uzi Benziman, one of Sharon’s biogrephers, wrote: “Sharon believed that the top command wanted to keep the victor’s laurels away from him, and give the credit to Bren [Maj. Gen. Avraham Adan]” (Benziman, 1985, pp. 146-147).

Sharon claimed that in the years prior to the war, most of the IDF’s efforts went toward strengthening the armored corps at the expense of the paratroopers, which to him was a grave mistake. The paratroopers were those who brought to the IDF inventive and bold thinking, full of imagination and audacity. In the armored corps, argued Sharon, the emphasis is on the "metal"—the tanks and artillery, rather than on creative and daring thinking. This statement was clearly aimed to downgrade the prestige of his rivals—Generals David Elazar, Haim Bar-Lev, and Shmuel Gonen, who had all commanded armored corps regiments. “The conflict between the generals,” wrote Uri Dan, a journalist and close friend of Sharon,“[in essence reflected] the conflict between two schools of thought: the schematic concept of massive war of armor against armor, represented among others by Bar-Lev, against Sharon’s approach of special daring operations carried out by small units intended to strike the enemy with a lethal blow” (Dan, 1975).

Responding to accusations that he refused to follow orders, Sharon argued that there are cases when a commander has to disobey orders. He said that a commander should examine his "willingness" to carry out orders according to three criteria: a. to what extent the orders serve the best interests of the state; b. his commitment to the soldiers serving under his command; c. his obligation to his superiors. “When, during a war, I receive orders that are completely illogical, I know this is a result of the lack of awareness by the commanders of the actual battle conditions. Under these circumstances, these orders may lead to the loss of life of our soldiers. I cannot accept it, and I believe my duty to my men takes precedence over my duty to my superiors” (Goldstein, 1974).

These interviews posed a complex dilemma to the security establishment, and above all to Chief of Staff Elazar. Arik Sharon was not just “another general.” In 1973, when the war broke out, Sharon was already known as the decorated commander of Unit 101, which led many of the IDF retaliatory raids in the 1950s and formulated the IDF’s fundamental battle values. For large sections of the public he was seen as a daring and cunning military leader who brought about the decisive reversal in the Yom Kippur War by crossing the Canal. Gadi Bloom and Nir Hefez wrote: “After the ceasefire, Sharon’s popularity reached new heights. For many Israelis, Arik was the big winner of the war, the man who crossed the Canal and defeated the Egyptians” (Bloom & Hefez, 2005, p. 283).

The security establishment was aware of its limited ability to restrain Sharon, and it could not allow itself to be seen as trying to prevent legitimate criticism of the serious shortcomings exposed during the war. Naturally, against a background of the harsh disputes relating to the Yom Kippur War, and the awareness of many members of the government who were intensively involved in the process of the decision making leading up to the war that their political careers might be jeopardized, the public response to Sharon’s statements was extremely extensive. Many in Israel identified with his views, while many others rejected them outright. Few remained indifferent.

Sharon’s critics argued that as a politician he was motivated mainly by personal political considerations rather than professional military analysis. Apart from that, they claimed that even if he was right on some of his allegations about the war, it was not proper to express them during or shortly after the event, particularly as the objects of the criticism were officers who had fought shoulder to shoulder with him in a war filled with blood, sweat, and tears. Journalist Daniel Bloch (1973) wrote: “No army would allow military and political disputes to be made public right after a campaign….I don’t know who started those disputes. But even if [Sharon’s] opponents started it, there is no justification for giving defamatory interviews either in the foreign press or in the local press, which would harm the reputation of many officers who were willing to sacrifice their lives for the state.” Bloch did not explain how Sharon was therefore supposed to defend his good name against his many critics.

The "war of the generals" occurred while an unprecedented political drama was underway behind the scenes, unbeknownst to the general public and probably also to many government ministers. On January 16, 1974, President Sadat relayed an oral message to Prime Minister Golda Meir by means of US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. “This is the first transmission from an Egyptian president to an Israeli leader,” Sadat said. “When I started my political initiative in 1971, I meant it. When I threatened war, I meant it. And now that I am speaking of full peace between us, I mean it. There has never been any contact between us. Now we have Kissinger, whom we both trust. I suggest that we both use his services and conduct a dialogue through him, and thus we will not lose touch with one another” (Meir, 1974).

On January 18, 1974, Meir sent a reply to Sadat, again through Kissinger. “I am well aware of the significance of a message to the Prime Minister of Israel from the President of Egypt,” she wrote, “It gives me much satisfaction. I hope that these contacts between us continue and lead to a turning point in our relations. For my part, I will do my best to create trust and understanding between us. Both peoples need peace. We must direct all our efforts toward achieving peace. We are lucky to have Kissinger, whom we both trust, and who is prepared to contribute his skills and wisdom toward achieving peace” (Meir, 1974).

In the media at the time there were reports that the Arab world was hoping that the Golda Meir government would remain in office, in order to promote a political settlement in the region (“Arabs Want G. Meir,” 1974). It seems likely that Meir and Dayan hoped they would be able to promote a political settlement with Egypt that would atone for the blunders of the Yom Kippur War. However, hostility toward the “government of failure” was too great, and the anger and extreme emotions gave Golda Meir and her government no chance of survival. It is impossible to know if a golden opportunity to achieve an Arab-Israeli political settlement immediately after the war was missed due to the public protests that swept through the country at that time.

The Government Deliberations

On the agenda of the January 27, 1974 government meeting were Arik Sharon’s statements. The transcript of the deliberations covers more than seventy pages and shows clearly that Sharon’s reflections—against the background of growing public protest against the “government of failure” and Sharon’s enhancing political status—touched very sensitive nerves in Israel's leadership. It is hard to understand why government ministers were swept into such a wide-ranging debate, when it was clear to them that the very fact that such a debate is taking place and its heightened publicity would necessarily cause a chain reaction. This would most certainly enhance the political and public power of the main subject of the debate and its principal target for criticism, Ariel Sharon.

Prime Minister Golda Meir

Prime Minister Meir opened the meeting by complaining about ministers who had leaked to the media the arguments about to be raised in the government meeting: “It makes me angry to realize that the arguments you wish to raise in the government session are leaked to the press before the session takes place." At a different time, Golda Meir stated, I would not have allowed those minister to present their case in such a situation. However, due to the gravity of Sharon’s statements, this time I would allow the arguments to be raised." In the future, Golda Meir warned the ministers, she would not allow them to speak (Government Meeting, 1974).

It is doubtful whether Meir believed that her threats were effective in the circumstances following the war. Her political and public stature and her ability to impose her authority on the ministers were severely damaged due to the war. The public arena and the media had become central to all the politicians, to a large extent at the expense of state institutions such as the government and the Knesset. No minister could ignore this important arena, even if it was damaging to the government’s regular work, and the ability of ministers to discuss matters discreetly.

Sharon’s criticisms put the Prime Minister in a difficult position of conflicting interests. The fact that Sharon’s allegations focused on then-Chief of Staff Elazar and his predecessor Bar-Lev was very convenient for her and Defense Minister Dayan.

After the war, even Golda Meir’s closest confidant, Yisrael Galili, tried to shake off the stigma of being a member of “Golda’s kitchen” (the team comprising Golda, Dayan, and Galili), which was held by many as responsible for the improper decision making process before and during the war. This followed a critical article by Prof. Shlomo Avineri, who wrote: “During the Golda Meir period, the government became a marginal body, and its status was rather low. The strongest body, in which the real decisions were taken, was the “kitchen of Golda Meir,” which was composed of Prime Minister Golda Meir, Defense minister Moshe Dayan, and Minister without Portfolio Yisrael Galili. where the important decisions were made. This trend reached a catastrophic peak just before the Yom Kippur War….The insolence and the arrogance of this, the assumption that political insights were the monopoly of a small number of people and that there was no need for consultation, was the worst kind of bad counsel” (Galili, 1974).

Sharon’s criticisms put the Prime Minister in a difficult position of conflicting interests. The fact that Sharon’s allegations focused on then-Chief of Staff Elazar and his predecessor Bar-Lev was very convenient for her and Defense Minister Dayan (Dagan, 1974; Dan, 1974b). Indeed, the need to distinguish between the responsibility of the political and military levels eventually became a central theme of the arguments she and Dayan put to the Agranat Commission. Meir also claimed that as a civilian with no military knowledge or experience, she could not be expected to counter the positions expressed by experienced military personnel such as Dayan, Elazar, Bar-Lev, and Eli Zaira (Maariv, 1974a).

Dayan for his part tried to deny direct responsibility for the failures of the war, inter alia by claiming that the Defense Minister’s responsibility for what happens in the IDF is less than his responsibility for what happens in the Ministry of Defense. The Chief of Staff, he argued, is appointed by the government and subordinate to it, in theory and in practice, on most matters. The Chief of Staff has the right and the duty to oppose the Defense Minister’s position presented to the government, which makes its decisions based on a majority opinion. In many cases, and on decisive questions, the government makes decisions based on recommendations from the Chief of Staff, in opposition to the views of the Defense Minister (Eshed, 1974b; Zadok, 1974; Shamir, 1974).

On the other hand, alongside her concealed satisfaction with Sharon’s remarks, Meir was well aware of the power in the hands of Sharon’s opponents inside and outside the government, above all members of Ahdut HaAvoda, the independent liberals, and Mapam, Ministers Victor Shem Tov, Yisrael Galili, Yigal Allon, and Moshe Kol, and Chiefs of Staff Bar-Lev and Elazar. They were backed by powerful public and economic institutions headed by the Kibbutz Movement. They all urged the Prime Minister, sometimes openly and blatantly, sometimes implicitly, to fire Defense Minister Dayan and unequivocally stand with the Chief of Staff and his supporters (Avidan, 1974).

The impression is that their words concealed a clear message: if Meir agreed to “sacrifice” Dayan, they would support her desire to keep her job; otherwise, they would initiate and support calls for her resignation. Although the elections of December 31, 1973 showed broad public trust in Meir, the Prime Minister felt, and rightly so, that her government’s stability rested on a weak foundation. In these circumstances, even a strong and authoritative leader like Golda Meir preferred to avoid confrontation with any of the parties.

Meir’s words at the government meeting reveal her effort to dodge the attack. She was strongly critical of Sharon’s non-collegial conduct during and after the war, but repeatedly stressed that she lacked the military-professional tools to judge the allegations, whether by him or against him. Indirectly and implicitly, the Prime Minister was sending a message that she questioned her trust in the military leadership, headed by the Chief of Staff. This point about her lack of military knowledge and understanding was eventually repeated by Meir in her testimony to the Agranat Commission, as a way of clearing her of any guilt for the “failure.” The overall impression is that the tenor of her remarks about Sharon was fairly lenient, showing a desire to contain the incident (Government Meeting, 1974).

According to Meir, in historical terms Sharon’s statements were especially unusual. They “called on soldiers to rebel and gave them every reason not to recognize the army’s command.” She related that during a visit to Sharon at his division, he began to talk about his disagreements with other generals and with the Chief of Staff. “I stopped him; I said: if I let you carry on like this in the presence of commanders, then I am giving the Prime Minister’s approval to a political rather than a military argument. I ask you to stop,’ and he stopped” (Government Meeting, 1974). It appears the Prime Minister’s implicit message was clear: if anyone could restrain Arik Sharon, it was she, by the power of her authoritative personality and her political experience. It would therefore be better for the ministers to ensure the government’s stability and her continuation in office.

Later, Meir addressed the Chief of Staff in the name of the government, asking him to refrain from arguing with Sharon. Her interest in containing the event is clear, but she did not clarify how the Chief of Staff was supposed to defend his reputation against Sharon’s harsh attacks on him. The compliments she paid to the Chief of Staff were likely intended to encourage him in his hour of darkness, and perhaps also to persuade him that it would be better to suffice with the government’s expression of support and avoid further disputes with Sharon. However, in her words she referred explicitly to Elazar’s ethical character, over which as far as is known there was no disagreement, and not to his performance before and during the war—the issue at the heart of the criticism. In a statement that smacked of lip service given the difficult situation encasing Elazar, Golda stressed that the government had “full confidence in the Chief of Staff and appreciation of all his actions before and during the war” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Meir was aware that the Agranat Commission could reach different conclusions regarding the responsibility for the failures of the war. She could not rule out the possibility that while regarding the military echelon as primarily responsible for the failures of the war, the Commission would, at least partly, put the blame on the political echelon. Thus, she chose to clarify explicitly that the government would stand by its positions on this issue, thereby hinting that she might contradict the Commission’s conclusions if she thought they were unjustified: “There is now a commission of inquiry,” she said, “I don’t know what they’ll say about me, I don’t know what they’ll say about the Defense Minister, I don’t know what they’ll say about the Chief of Staff. I don’t know what they’ll say about anything. But this government, sitting round this table, will continue to make its view loud and clear” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Later, Meir decided to condemn Sharon’s criticism of former Chief of Staff Bar-Lev. In that context she revealed that Sharon had supported Bar-Lev’s appointment after the Six Day War. Meir said that when she was secretary of the party, Sharon, who was then a general in active service, tried to persuade her to oppose the appointment of another general who was a candidate for the position (apparently referring to Ezer Weizmann): “He came to me in a raging fury, saying, for God’s sake, just not him.” When she asked him whom he recommends for that position, Sharon named Bar-Lev. It later became clear that this was not a one-time random interchange. Nevertheless, neither Meir nor any of the ministers felt they should address the problematic fact that a senior IDF officer in active service had directly contacted a senior member of a political party in order to promote his candidate for Chief of Staff. Meir said: “That didn’t stop him from speaking just as furiously to me against Bar-Lev three months later” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Meir then turned to Sharon’s assertion that he, and only he, should be recognized as the one to rebuild the IDF in its time of need: “He can think that he’s the only one, that there’s nobody like him, and that there neither is, nor will be, any suitable Chief of Staff in the IDF unless it is Arik Sharon. But [we cannot accept] this act without restraint, internally and externally, with an ideology of disobeying orders….He [believes he] was declared king of Israel. OK. When we become a kingdom, he either will or will not be the king of Israel….Is that the proper way to talk about former commanders, about the current Chief of Staff, what is this [kind of behavior]?….And there’s only one man who can do it [be Chief of Staff] and that’s Arik Sharon. But for political reasons they [we] won’t let him. That means we’re all rather like traitors, because political matters are more important to us than the IDF and national security” (Government Meeting, 1974). In a letter Sharon sent the Prime Minister a few months later, he confirmed her account: “I think,” he wrote, “that it is vital to appoint as Chief of Staff a commander who can deal with the problems facing the army, which are worse than anything we saw in the past. In my opinion, I can do that better than any other candidate” (Oren, 2021).

Regarding Chief of Staff David Elazar, Meir added: “I saw how he presented matters, and I saw him from very close up during the war. I have no authority to judge military actions, but I hope that Israel’s future chiefs of staff will be no less worthy in all aspects [that characterize the current Chief of Staff]—ethics, truth, and responsibility. I would say to him, don’t take what Sharon said to heart. But ultimately this would not be a fair request because there are people who read it [Sharon’s allegations against him] and don’t know the Chief of Staff [and therefore would get a wrong perception about his performance in the war]. But anybody who knows you, thinks like I do” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Chief of Staff David Elazar

Given the floor, the Chief of Staff began by thanking the Prime Minister for her words of encouragement, and said that such support was particularly important in view of Sharon’s call for his resignation. He claimed that Sharon’s rhetoric was full of distortions, and while he was not too riled by this criticism, he could not ignore it, particularly the call for his resignation. Elazar’s words revealed his weakness at this difficult time. Meir’s own status was fairly shaky, and it is doubtful whether she had the public backing to lend him any support. Besides, the words of support and praise she gave Elazar “in the name of the government” only highlighted the fact that his direct superior, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, kept quiet. In fact, the general impression in reading the government document is that Elazar was fairly isolated in the battle for his reputation.

Elazar’s apologetic response made his weakness even more apparent. Someone like him, who had lived through a number of dangerous battles and many times risked his life for the country was forced to justify himself before government ministers who were probably not experts in his actions during the war.

In his predicament, Elazar was forced to base his accusations against Sharon on complaints sent to him by his bitter rival, Gen. Gonen, whom he had dismissed from his post early in the war. Elazar reiterated Gonen’s allegations that Sharon had launched military attacks without command approval. These attacks failed and involved heavy losses to the IDF. Elazar clarified that he did not accept the suggestion to investigate this subject as part of the inquiry into the war; his purpose was to focus the blame on Sharon. It was clear to him that the Commission’s inquiry might reveal defects in his own conduct and decisions. In any case, it was reasonable to assume that the inquiry would examine the conduct of many elements, and thus cloud Sharon’s personal responsibility. He was also probably worried that a legal inquiry would be widely publicized, look like vengeance on a personal rival, and damage the morale of IDF soldiers, who were under great pressure due to the possible renewal of war (Government Meeting, 1974; Davar, 1973).

In the end, Elazar decided to leave this matter to the Agranat Commission. He had a personal meeting with the Commission’s chairman, Supreme Court Judge Shimon Agranat, and sent him the detailed complaint. After consultation with Commission members, Judge Agranat announced that: (a) the Commission would discuss the issue of obeying commands up to the blocking stage [October 8, 1973]; (b) the Commission would not discuss the question of whether it was militarily correct to issue this or that command; (c) the Commission would discuss the issue when the time came, according to how it decided to proceed; (d) obviously the Commission’s inquiry would not prevent other steps being taken as required by law. Interestingly, none of those present, including the Attorney General, felt it worth noting that the Commission’s chairman had a personal meeting with one of the main subjects of the inquiry he chaired (Government Meeting, 1974).

Finally, Elazar referred to Sharon’s criticisms of his performance as Chief of Staff during the war, and particularly the fact that he did not visit the front enough times, ostensibly implying that Elazar was afraid of being too close to the battle areas. Elazar’s apologetic response made his weakness even more apparent. Someone like him, who had lived through a number of dangerous battles and many times risked his life for the country was forced to justify himself before government ministers who were probably not experts in his actions during the war: “General Sharon well knows that the situation of the Chief of Staff in battle is different from the situation of the Defense Minister. The Chief of Staff must be in constant contact with the corps commanders and the Command generals. Nevertheless, every day, without exception, I managed to be either in the north or in the south, and usually at both fronts. I was also in the division command posts, and I also found time to go to Bren [General Avraham Adan, a leading commander on the southern front] and also to Arik and even get fired on in the helicopter” (Government Meeting, 1974).

And then Elazar got to the “elephant in the room”: the deafening silence of the Defense Minister Moshe Dayan in response to Sharon’s harsh allegations. According to Elazar, Sharon’s words demanded a response from the Defense Minister. His request from the Defense Minister for support in these difficult times showed his distress caused by the Yom Kippur War. He had no choice; he was grasping at straws. He could assume that the Defense Minister wished to ensure that he, the Chief of Staff, would bear the blame for the failings of the War and would not support him. Moreover, he was well aware that Dayan’s situation was no less difficult, as his public standing was undermined. Even if the Defense Minister wanted to support him, his support would probably have had no effect at the public level (Government Meeting, 1974).

Sharon’s conduct in the Yom Kippur War, according to Elazar, was not unusual for his character: “Arik’s career,” he clarified, “is full of breaches of discipline, some serious, some known, and some unknown.” Even Sharon’s claim about the politicization of the IDF was refuted, said Elazar. The best proof was the fact that senior officers who had recently left the IDF had turned to a range of parties. In the end, he said, the problem lay in one man, Arik Sharon. And the best evidence is the fact that there were no conflicts of opinion in the Northern Command, none in the Central Command, none in the Air Force, none in the Navy, and none in the Armored Corps. There was only one place where there were “wars of generals”—in the Southern Command, where Gen. Sharon served (Government Meeting, 1974).

Haim Bar-Lev and Yigal Allon

The next speaker was Haim Bar-Lev, a minister in the Meir government and former Chief of Staff, who was appointed Commander of the Southern Front a few days after the war began. He said that two days after taking over the Command, he recommended to the Chief of Staff that Sharon be dismissed from his post as divisional commander. However, he was told (though not clear by whom) that “for certain considerations it was decided not to do so….I wouldn’t have given such a recommendation if I thought he was an excellent division commander. I was hardly impressed with him in this job. On this matter, my view was different from that of the Defense Minister.” He later called Sharon’s statements “extremely grave” and expressed concern about their ramifications for the IDF. According to him, many IDF officers had asked him “how long will you let this person [Sharon] run wild without saying anything”? (Government Meeting, 1974; Marshall, 1974).

Bar-Lev claimed that Sharon’s position in arguments with other generals was not symmetrical: Sharon had an advantage because “he has no limits that might restrain him, while every one of us has limits.”

Bar-Lev hinted at criticism of Golda Meir and directly criticized Dayan for lack of firmness and determination in confronting this matter: “Our address of this issue so far was certainly insufficient.” Bar-Lev claimed that Sharon’s position in arguments with other generals was not symmetrical: Sharon had an advantage because “he has no limits that might restrain him, while every one of us has limits.” Due to these constraints, he reached the same conclusion as Chief of Staff Elazar, that “for the sake of the army and the sake of the country, this matter must be handled at the national and legal level.” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Sharon, Bar Lev stressed, had raised four issues: (a) politicization of the army, (b) rigid military thinking, (c) obedience to commands, and (d) action during the war. Of these issues, Bar-Lev argued the Agranat Commission could only deal with the fourth one, and even this—only until the blocking stage of the war. As for the other three issues, the Defense Minister must express his position. For six years prior to the war he had been Defense Minister, and during that time Bar-Lev served four years as Chief of Staff, and David Elazar about two years. In order to rebuff allegations of politicization, Bar-Lev claimed that all the generals who served at the same time as he did and later turned to politics went to the right wing party Gahal. Among others, he mentioned Ezer Weizmann and Shlomo Lahat. While Elazar was Chief of Staff, two former Irgun members were made generals—Kalman Magen and Avraham Orly. Unintentionally, Bar-Lev also clung to apologetic arguments, instead of attacking Sharon as someone who quite early in his military career had been very politically involved. In order to refute the allegations of promoting “Armored Corps people” over paratroopers, Bar-Lev mentioned his promotion of two paratroopers—Motta Gur and Yitzhak Hofi—from colonel to general (Agres, 1974; Government Meeting, 1974; Rosen, 1990).

Bar-Lev believed that Gen. Gonen’s complaints should be handled like any complaint in the IDF—by an investigating officer and not a commission of inquiry. Once the Commission published its report, he maintained, this issue could become irrelevant. In any case, its conclusions on this issue would be part of many issues handled by the Commission, and it would not receive the approriate level of public attention it merits. Finally, Bar-Lev referred to the new “model” of obeying commands that Sharon tried to define. If there was no response to this, Bar-Lev warned, “it will have enormous negative implications, on the performance of the IDF.” Bar-Lev believed that such statements could not be left without a response, and a response from Chief of Staff Elazar would be considered irrelevant because the current Chief of Staff was in dispute with Sharon, so it would look like a “conflict of interests.” Therefore “the clear response” must come from the Defense Minister (Government Meeting, 1974).

Bar-Lev’s criticism of the government was backed by Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Allon: “I am not happy with the way that certain disciplinary problems were handled during the war and immediately afterwards. We are discussing the problem at a very late stage, when it has already become a sickness.” Allon gave an example from the history of the United States—the dismissal of General MacArthur by President Truman, which in his opinion showed the proper relationship between the political and the military echelons. Allon noted that during the Sinai Campaign, Chief of Staff Dayan had dismissed a brigade commander who acted improperly: “No responsibility resembles that of a commander in times of war. Sometimes there is a moment when you are alone, and you know that you must take difficult decisions with everything that entails.” Allon did not dare to point an accusing finger directly at Prime Minister Meir, but only stated that “we are all responsible for everything, as a collective, with mutual responsibility, as comrades” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Allon placed the main responsibility for the poor handling of Arik Sharon’s behavior on the Defense Minister and the Attorney General, who had been too lenient with him. “For some reason,” said Allon, “the Defense Minister chose the role of traffic cop. He rolled the issue back and forth between the Chief of Staff and the Attorney General. It’s not enough…when the Defense Minister [says] in public that ‘nobody died because Arik Sharon gave interviews to the New York Times’….What does this nice and forgiving comment mean…It’s like a permit to show contempt for military discipline.” In response to Sharon’s defamatory remarks, Allon said that the Defense Minister claimed that “he did not replace a single officer as a result of the war,” even though everyone was aware of the dismissal of Gen. Gonen: “That’s one of the most serious things that happened [durnig the war],” said Allon (Government Meeting, 1974).

Allon continued: “Sharon’s philosophy of selective discipline [is an extraordinarily severe statement]. We have not heard of such a philosophy in our ranks since the pre-statehood period. Of all senior IDF officers, perhaps I experienced the most difficult challenge. I was utterly opposed to the decision [of Ben-Gurion during the War of Independence] to break up the Palmah, but when I got the order, I executed it.” Allon clarified that he was not very familiar with Gonen’s suitability for the position of the commander of the southern front, He had heard good things about him from Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin: “I met him on a tour of Sinai with Levi Eshkol. I didn’t like everything he said. I wasn’t sure if his appointment as GOC of the Southern Command was auspicious at that time. But we don’t appoint Command Generals. The government doesn’t do that” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Allon criticized the willingness of Attorney General Meir Shamgar to meet with Sharon, after he [Sharon] refused to meet with a representative of the Chief of Staff: “Undermining discipline on the southern front [in wartime] cannot only be judged by a legalistic criterion….These are military personnel with control over human lives, and the fate of the country.” How can it be, he wondered, that they excuse a general who refused to obey a command from the Chief of Staff, and instead the Attorney General invites him to discuss a rapprochement with the Chief of Staff (Government Meeting, 1974). Referring to the clash between Sharon and the GOC of the Southern Command, Allon said: “Even today I’m not prepared to say who was right, Gorodish or Arik, but can we just overlook a complaint from a Command General against a commander who is subordinate to him? Can we just bring an end to this debate with a talk between the GOC and the divisional commander, and a half-hearted reprimand?”

In the end, Allon was prepared to let the members of the Agranat Commission handle the issue on condition that they extended the time framework of their inquiry up to the ceasefire. Allon suggested that Prime Minister Meir, who was also serving as Minister of Justice, discuss the matter with the Commission chairman. None of the ministers saw anything wrong in a personal meeting between the Prime Minister, one of the main subjects of the investigation, and the Commission chairman (Government Meeting, 1974).

Attorney General Meir Shamgar

The deliberations were joined by Attorney General Meir Shamgar. He said he had told the Chief of Staff that “a soldier who has criticism of the actions of his senior officers can raise his reservations through the command channels, but is forbidden to expose internal military disputes to elements outside the army” (Maariv, 1974b). Therefore the Chief of Staff can summon Sharon, let him state his claims, and reprimand him for his statements (Government Meeting, 1974). Shamgar clarified that Gen. Gonen’s complaints of Sharon’s refusal to obey to his orders cannot be investigated in the legal context alone, but must also consider prevailing circumstances in the battlefield and its outcomes. These areas are better suited to the Agranat Commission. Shamgar added that it must be remembered that “the Attorney General is not a machine for filing cases” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Shamgar’s statement shows clearly that he was uncomfortable with Elazar’s focus on the legal dimension, in his intention to harm Sharon’s credibility and deter him from further criticism of the present Chief of Staff and his predecessor. These issues, he believed, relate to personal struggles for positions of power and legitimate disputes over military moves necessary in times of war. It is doubtful if they can be resolved at a legal level, particularly in view of Sharon’s political status at that time. Elazar himself testified that Sharon announced “his refusal to give evidence to any investigating officer, commission of inquiry, or arbitrating officer” (Government Meeting, 1974).

In these circumstances, Shamgar had advised Elazar to summon Sharon for a personal talk. Elazar accepted this suggestion, but it was precisely at this important meeting that Elazar revealed his weakness, perhaps even his naivete, regarding Sharon. Instead of using his superior position to put Sharon in his place, and demand an apology for his harsh words, the Chief of Staff satisfied himself with a vague promise from Arik Sharon that “he won’t give more interviews.” As might be expected, Sharon did not keep his promise and continued to express his opinions in the media (Government Meeting, 1974).

Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Allon’s severe criticism of him angered the Attorney General and led him to an explicit threat of resignation: “Sitting here there are members of the government who have worked with me for five years. I don’t think I have let anybody down. If there is a different conclusion, I am free to leave. I am sorry that I cannot respond to this as I am a civil servant." The Prime Minister was probably shocked at the possibility of the Attorney General resigning at this difficult time, and was quick to explain that she hopes that “Allon was not hinting at any deliberate sabotage [by the Attorney General]’” (Government Meeting, 1974).

Defense Minister Moshe Dayan

Clearly the criticisms from Bar-Lev and Allon about the lack of support from the political echelon for the military echelon, and particularly for the Chief of Staff, demanded a response from Defense Minister Dayan. It appears that his reluctant response was a form of lip service. His words sent a clear message: at the bottom line, Sharon’s contribution to national security was very important to the war effort. Under the circumstances, perhaps Sharon’s conduct does not conform to “the rules of protocol,” but that is a disciplinary matter. It certainly does not justify setting aside his contribution to the nation’s security and demand his resignation from office.

Defense Minister Dayan agreed with Elazar that “there is no basis for [the allegation of] politicization of the IDF, in promotions or in appointments or in the posting of generals. It never occurred to anyone to think of [making decisions in this regard on the basis of] political considerations” (Government Meeting, 1974). It is doubtful whether Dayan himself believed in this sweeping statement. He knew very well that political considerations did play a role in the appointment of high ranking officers in the IDF. He went on to clarify that Sharon did not want to leave the army. He wanted to fulfill additional roles in the army and become Chief of Staff. However, Dayan continued, I explained to him that because of his intensive political involvement, his chances of becoming Chief of Staff were nil (Sarid, 1974). Dayan chose not to remind the government that he himself had hoped to be appointed Chief of Staff at the end of 1953, even though he was number ten on the Mapai list for the 1st Knesset. Indeed this fact led a number of ministers to object to his appointment as Chief of Staff (Shalom, 2021).

Regarding Sharon’s allegations about fossilized thinking in the IDF, Dayan stated, it’s legitimate to say there is some rigidity in the Ministry of Defense and in the IDF.

Dayan clarified that even before publication of Sharon’s interviews, he had publicly expressed his confidence in the Chief of Staff, and he saw no reason to remove him from his post. As for legal actions, Dayan stressed that he would follow the instructions of Attorney General Shamgar. On the subject of following orders, Dayan said “the maintenance of discipline in the IDF is absolutely fundamental.” He revealed that following Bar Lev’s appointment as the commander of the southern front he told him that “if he decides that Sharon must be removed, then do so.” However, he continued, Bar-Lev was in no hurry to remove him (Government Meeting, 1974).

Regarding Sharon’s allegations about fossilized thinking in the IDF, Dayan stated, it’s legitimate to say there is some rigidity in the Ministry of Defense and in the IDF. I also sometimes expressed my critical opinion of certain conceptual approaches in the IDF. [However] it’s funny to hear these allegations coming from Arik Sharon who served as the head of the Training Department. He was the one who [shaped] the IDF doctrine of warfare. He served in this position until he was appointed GOC of the Southern Command. If anyone shaped the IDF combat doctrine, it was he” (Government Meeting, 1974; Bar-On, 2014, p. 276).

According to Dayan, the decision to remove Gorodish was made by the Defense Minister, and Sharon was not involved in it in any way (Government Meeting, 1974; Schiff, 2003). “In my opinion,” said Dayan, “Gorodish was unable to command the Southern Command in a war of this scale” (Government Meeting, 1974). Apart from that, Gorodish was obliged to exercise authority and the ability to command older and more experienced commanders, each of whom was an individualist. Greater commanders than he would have problems imposing discipline on a general like Arik Sharon” (Zeevi, 2000).

Against this background, Dayan explained, it was decided to appoint Haim Bar-Lev as commander of the Southern Front. “And that was one of the most important decisions we made.” When Haim Bar-Lev ended his role in the Southern Command, he was replaced by Gen. Yisrael Tal (Talik). But Talik, so Dayan implied, did not meet the government expectations, and he was replaced by Bren (Avraham Adan). Dayan summarized: “The southern front was difficult and complex, and Israel is allowed [to ensure] that it has the most suitable commander available in the army for this highly important position. Had Gorodish proved to be the most talented he would have remained in office. And if Talik had proven himself, I would have asked him to stay. But forgive me, I thought he wasn’t doing it, and that Bren would be better” (Government Meeting, 1974).

As far as Sharon’s personality was concerned, Dayan said that “Sharon is one of our best field commanders, and there is no hint of disagreement between me and the Chief of Staff on that, and if there is, I want the Chief of Staff to tell me so. We are at war with the Arabs. If Arik Sharon gave an interview, that must be examined. But I’m not prepared to throw him out of the army for that reason….If you’re talking about interviews, you may take many other books written about the war, and you’ll find in them passages from interviews given by many senior commanders in the IDF ….I may agree with everything said against Arik, but [I don’t accept] that he’s the only one who reflected criticism about decisions undertaken in the war. Government ministers visited the divisions and heard briefings from the generals. I heard they were shocked by things some commanders said about Arik….It would be possible to fill a book with the defamatory remarks they heard. If necessary we’ll put him on trial. But there is [a long way to go] in deciding to throw him out from his position as a division commander.” In any case, Dayan reminded the government that the issue should be referred to the Attorney General (Government Meeting, 1974).

Eventually, as expected, “most ministers believed that the government should not be involved in the affair of complaints against Gen. Sharon, and the decision was in the hands of the Chief of Staff David Elazar” (Eshed, 1974a). Under these circumstances, the government passed a resolution with the following main points: (a) The government as a whole has full confidence in Chief of Staff David Elazar. It appreciates his actions before and during the war. (b) The government rejects Sharon’s statements about the circumstances under which commanders should follow orders. His views in this regard reflect an ideology that is unacceptable to the IDF. (c) Allegations and criticisms on matters of the war will be investigated by the Agranat Commission. Therefore there is no reason to raise accusations in the press. (d) The Defense Minister and the Chief of Staff refuted Sharon’s words about “rigidity” of thinking in the IDF as having no basis. (e) The Defense Minister and the Chief of Staff also rejected the allegations of IDF appointments based on political criteria (Government Meeting, 1974).

Conclusion

The State of Israel has vast experience with security events, including those that led to difficult and costly wars. Naturally, these campaigns have included successes as well as failures. In all cases internal disputes arose between the military personnel who participated in the campaign and people in the civilian arena. There were highly publicized internal disagreements between David Ben-Gurion as Prime Minister and Defense Minister, and the heads of the Palmah Yisrael Galili and Yigal Allon (Shalom, 2002, pp. 657-678); between Moshe Dayan as Chief of Staff and General Assaf Simhoni, who was the GOC of the Southern Command during the Sinai Campaign (Blau, 2006); between Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin and GOC Southern Command Yeshayahu Gavish just before the Six Day War, down to the harsh disagreement during the Second Lebanon War between Chief of Staff Dan Halutz and GOC Northern Command General Udi Adam.

Yet the “war of the generals” that accompanied the Yom Kippur War, mainly due to the sense of failure it engendered and the heavy IDF losses, was the most severe of all in the harshness of the accusations hurled by and among senior commanders, and in the public response they aroused. Moreover, and more than in any other incident, in the “war of the generals,” an effort was made to channel the struggle between the generals to a legal forum in order to neutralize Gen. Ariel Sharon, who was a central element in the debates surrounding the Yom Kippur War. Ultimately it became clear that this direction was not suitable for the "solution" of disagreements between army officers over actions in wartime. It is doubtful whether such issues can ever be fully decided in any way, and perhaps they should be left to public debate and historical research.

Clearly such controversies cause severe damage to Israel’s deterrent image in the eyes of its enemies. In an age when the struggle for public opinion is a central element for determining victory or defeat, struggles among generals encourage the enemy in various ways: a. by highlighting the IDF’s failures in battle; b. by emphasizing the fact that the senior ranks are not operating in an atmosphere of unity and cooperation, among themselves and with the political echelon; and c. insofar that many of the arguments between the generals lead to the exposure of security secrets.

The existing political culture and legislation in Israel do not obstruct “wars of generals,” such as the one that followed the Yom Kippur War. Presumably such "wars" will emerge in future conflicts as well, and be harmful to the best interests of Israel. Thus, it seems that only strict and uncompromising legislation can restrain this phenomenon in the foreseeable future.

*The author wishes to thank Ben-Zion Borochowitz, Amit Olami, Yafim Magril, Michal Bakshi, Shai Shoval, and Ben Miro, who assisted him in his research.

References

Agres, E. (1974, January 27). The accuser becomes the accused. Davar [in Hebrew].

Avidan, S. (1974, April 8). Letter to Prime Minister Golda Meir. General Federation of Labor in the Land of Israel, National Kibbutz Hashomer Hatza’ir, personal archive—Golda Meir, National Archive [in Hebrew].

Arabs want G. Meir to continue in office (1974, March 6). Davar [in Hebrew].

Barnea, N. (1973. November 11). Sharon accuses the IDF command of missing the chance of an absolute victory. Davar [in Hebrew].

Bar-On, M. (2014). Moshe Dayan: A life 1915-1981. Am Oved [in Hebrew].

Bar-Yosef, U. (2013). Historiography of the Yom Kippur War: Renewed debate on the operational and political failure. Studies in Israel’s Revival: Anthology of the problems of Zionism, the yishuv, and the State of Israel, 23, 1-33 [in Hebrew].

Bashan, R. (1974, January 25). The cancellation of my appointment as division commander: A grave step. Yediot Ahronot [in Hebrew].

Benziman, U. (1985). Sharon: Doesn’t stop on red. Biography of Arik Sharon. Adam Publishers [in Hebrew].

Bergman, R., & Meltzer, G. (2004). The Yom Kippur War: Real Time. Miskal, Yediot Books [in Hebrew].

Blau, U. (2006, January 21). Simhoni, the last battle. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/1.1114882 [in Hebrew].

Bloch, D. (1973, November 13). Arik Sharon’s opening shot. Davar [in Hebrew].

Bloom, G., & Hefez, N. (2005). The shepherd: The life story of Ariel Sharon. Yediot Ahronot, Hemed Books [in Hebrew].

Buhbut, A. (2015, September 21). Gorodish after the Yom Kippur War: “Remove Sharon, he refused an order.” Walla. https://news.walla.co.il/item/2891849 [in Hebrew].

Dagan, D. (1974, January 21). Arik Sharon: Agreement with the Egyptians cannot be based on belief in Sadat’s intention for peace. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Dan, U. (1974a, May 19). The Next War. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Dan, U. (1974b, December 9). On October 8 the chance to defeat the Egyptian army was missed. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Dan, U. (1975). The bridgehead: How defeat was turned into victory. A”L Special Publication [in Hebrew].

Davar. (1973, November 22). Golda Meir: The war could restart at any time. Davar [in Hebrew].

Davar. (1973, October 7). The parties halt their election campaigning. Davar [in Hebrew].

Dayan, M. (1982). Moshe Dayan: Milestones. Idanim [in Hebrew].

Elazar, D. (1973, January 20-21). Letters to the Defense Minister and the Chief of Staff. Personal archive—Golda Meir, National Archive [in Hebrew].

Elazar, D. (1974). Order of the Day from Chief of Staff Major General David Elazar. Maarachot, 236. https://fliphtml5.com/gcjnv/cmcs [in Hebrew].

Erez, Y. (1973, November 11). The Defense Minister and the Chief of Staff order soldiers to avoid giving interviews. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Eshed, H. (1974a, February 3). The view of most Government Ministers, Gonen’s complaints against Sharon, under the authority of the Chief of Staff. Davar [in Hebrew].

Eshed, H. (1974b, February 15). Motti Ashkenazi and Moshe Dayan. Davar [in Hebrew].

Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee (1973, November 12). Minutes no. 341 of the Meeting of the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, at the start and end of a tour of the IDF Forces on the West Bank of the Suez Canal. National Archive. https://bit.ly/2TbuoNF [in Hebrew].

Galili, Y. (1974, January 7, 9). Letter from Minister Galili to Golda Meir. Personal archive—Golda Meir, National Archive [in Hebrew].

Goldstein, D. (1974, January 25). Interview of the week with Ariel Sharon. Maariv. [in Hebrew].

Government Meeting (1974, January 27). Minutes of government meeting 52/5734. National Archive. https://bit.ly/3kiRNYI [in Hebrew].

Kan Archive—Treasures of Israeli Broadcasting (2018, January 11). Ten years after the Yom Kippur War: Interview with Ariel Sharon on the New Evening program. YouTube. https://bit.ly/3xElzLi [in Hebrew].

Kan Hadashot (2019, October 8). The 9th day of the war—Defense Minister Dayan: “A war that is heavy in days, heavy in blood.” YouTube. https://bit.ly/3i2MARW [in Hebrew].

Kipnis, Y. (2016). The turning point in the inquiry into the circumstances of the Yom Kippur War. Studies in Israel’s Revival, 26, 41-80, https://bit.ly/3icp9FI [in Hebrew].

Lahav, P. (1999). Israel on trial: Shimon Agranat and the Zionist century. Am Oved [in Hebrew].

Maariv. (1974a, January 26). Golda: I’m not the same person I was before the war. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Maariv. (1974b, January 29). Attorney General gives ministers his opinion on Sharon’s interviews. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Marshall, S. (1974, February 17). The argument between the Israeli generals. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Meir, G. (1974, January 27). Golda Meir’s letter to Yigal Allon, exchange of messages between Anwar Sadat and Golda Meir through the USA. File 9-a/7026, National Archive [in Hebrew].

Oren, A. (2021, February 11). Meddler’s notebook: The letters of Arik Sharon. The Liberal. https://bit.ly/3qRpq4R [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office (1973, October 23). Prime Minister’s announcement in the Knesset on October 23, 1973. Prime Minister Golda Meir File 17-a/7244. National Archive [in Hebrew].

Rosen, E. (1990, April 9). Since the Yom Kippur War the armored corps has lost its precedence to the infantry: The reds have blocked the way to the Chief of Staff for the blacks. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Sarid, Y. (1974, January 27). Did you tell Sharon that he had no chance of being appointed Chief of Staff because of his political views? Maariv [in Hebrew].

Schiff, Z. (2003, August 8). The Gorodish recordings: Little new information, key questions remain open. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/1.901865 [in Hebrew].

Shalom, Z. (2002). On civil-military relations, military discipline, and fighting ethics. Studies in Israel’s Revival, 12, 657-678. https://bit.ly/3B0HuhN [in Hebrew].

Shalom, Z. (2021). Discussions before the appointment of Moshe Dayan as Chief of Staff—November-December 1953: Background, moves, and lessons. Yesodot, Studies in IDF History, 3. IDF History Department. https://bit.ly/2V1xiFe [in Hebrew].

Shamir, M. (1974, February 15). Motti Ashkenazi is not right. Maariv [in Hebrew].

Shemesh, M., & Drori, Z. (Eds.) (2008). National trauma: The Yom Kippur War after thirty years and another war. Ben-Gurion Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev [in Hebrew].

TAUVOD. (2013, October 10). Intelligence: What did we collect, what did we assess? Eli Zeira, “40 years after the Yom Kippur War”: Event held at the Institute for National Security Studies. YouTube. https://bit.ly/2U9uequ [in Hebrew].

Zadok, H. (1974, April 24). Opinion on ministerial responsibility. File 3-p/922, National Archive [in Hebrew]. Zeevi, R. (2000, October 24). Friendship: Shmuel Gorodish. Remarks in his memory on the ninth anniversary of his death. https://bit.ly/3wFh41u [in Hebrew].