Strategic Assessment

Programs to combat radicalization address social processes that create a tendency toward political violence, and in many countries they are incorporated as part of the fight against terror. Counter-radicalization programs are a tool whose efficacy has been tested and proven. Thanks to their side effect of limiting collateral damage by counterterrorism, anti-radicalization programs also yield multiple benefits: more security, fewer violations of human rights, and an enhanced horizon for reconciliation and peace. Nevertheless, there is no available information on any comprehensive policy on this matter in Israel. This is a problematic lacuna, both in terms of violence coming from Palestinian citizens of Israel and in terms of violence from extremist Jewish factions. Indeed, findings suggest that the establishment of a government entity in Israel for the purpose of studying and combating radicalization should be considered.

Keywords: radicalization, Islamic radicalization, political violence, terror, peace, Arab Israelis, Jewish-Arab relations

Introduction

Following the events and aftermath of September 11, 2001, programs were developed throughout the world to fight processes of radicalization that lead to violence, and they have been widely implemented. Complete information about these programs is still lacking, but a comprehensive report by a research network funded by the European Union describes 445 programs in the period 2004-2014 that were designed to reduce violence by extremist groups. Programs of this kind were implemented in dozens of countries, from Norway to Malaysia, and from Saudi Arabia to the United States. While most of the programs focus on the struggle against Islamic radicalization, there are also programs aimed at the extreme right wing, separatist groups, and more.

Israel, however, is significantly lagging compared to other countries when it comes to recognizing the importance and efficacy of anti-radicalization programs. This is despite the fact that the country experiences the problem (i.e., terrorism) far more severely than other countries that have introduced anti-radicalization programs, and in spite of the broad public engagement and the extensive resources directed at the prevention of terror and political violence. This paper shows how these programs have proven to be effective, to some degree at least, in a variety of national and social contexts, and it is therefore proper that Israel consider the development of a strategy to combat radicalization as an additional tool in the security toolbox, alongside the efforts to foil attacks, policing, and warfare. A highly successful war on radicalization would also reduce the burden on the security and counter-terror services.

Programs to combat radicalization have another benefit: an examination of the practical content of the programs shows that they can improve not only the security situation but also human rights, and ultimately even open a channel for reconciliation and peace, in a number of ways. First, the security improvement in itself means less physical and mental harm to non-combatant. Second, reducing the need for military or police actions also reduces the expectancy of damage to property and harm to the fabric of life of noncombatant, which often accompanies actions of this kind. Finally, many of the policy recommendations for combating radicalization are linked to improvements in human rights: anti-discrimination struggles, greater transparency, improved mental health facilities, more employment among marginalized groups, and encouragement rather than suppression of local identities. All these affect national security and help to strengthen it.

Typology and Features of Anti-Radicalization Programs

The definition of radicalization is controversial and a subject of ongoing research and empirical discussion. This paper adopts Clutterbuck's definition, whereby radicalization is understood as a complex, dynamic, and non-linear process of changes in an individual’s modes of thinking, leading over time to a significant alteration in his perception of the world and external events, and in his internal understanding of himself. These changes may be expressed in behaviors that in certain cases ultimately lead the individual to become involved in violence, violent extremism, or terror. Therefore the accepted terminology in the literature, based on the concept of radicalization, is confusing and even misleading: in the context of this paper, radicalization is not simply growing closer to radical attitudes (such as the desire to see profound changes in the economy or in society, for ecological, socialist, libertarian, or other reasons), but a tendency to approve of violence to achieve political goals, and a growing potential to commit such violence. In other words, it is a tendency toward political violence and not a matter of ideas that seek to bring about some fundamental change in the social order. It would perhaps be more correct to call this a struggle against fanaticism, but deradicalization is the term adopted in literature.

While anyone involved in violence deriving from extreme ideology has gone through a process of radicalization, only a minority of those who have been radicalized will ultimately engage in actual violence. This distinction is important for the development of programs against radicalization for people who have been through the process but have not become actively involved in violence or violent organizations.

Deradicalization

The term deradicalization is widely used to describe various kinds of programs designed to combat processes of radicalization that can lead to violence. However, experts propose distinguishing between three types of programs, based on the stage in the radicalization process at which intervention is attempted. Only one of the three is called deradicalization:

- Deradicalization: programs and responses whose goal is to reverse completed radicalization processes that have reached the level of involvement in violent action. They seek to stop the violence, rehabilitate those involved, and reintegrate them into society. They are mainly aimed at people who have been arrested, imprisoned, or taken captive. Recently a new category of foreign fighters has been added: citizens of various countries who traveled to fight in civil wars in other countries, such as Syria, and have returned to their native countries.

- Counter-radicalization: programs and responses intended to delay or stop the radicalization processes as they occur. They are relevant for transitional situations headed toward extremism or violence. Their goals include removing individuals from the extreme environment and re-integrating them into society. They are aimed at people identified as involved in extreme environments but who have not yet been arrested, imprisoned, or taken captive.

- Anti-radicalization: preventive programs and responses that intervene before the radicalization process begins, or in its early stages. These programs are intended for individuals or groups that have been identified as vulnerable or at risk of radicalization.

This division helps the understanding of not only the types of existing programs but also the target audiences that could be relevant for each type, and the different aims they may have. The literature includes another relevant distinction, between programs with a micro approach and programs with a macro approach:

- Micro: programs dealing with the struggle against radicalization at the individual level. They might include an emphasis on education, higher education, employment, and mental health care. Although they may be offered by local authorities, civil society organizations, or private organizations, the emphasis is always on the prevention of specific cases at various stages.

- Macro: programs aimed at structural factors in radicalization processes, such as improvements of macro-economic conditions and strengthening governance. Among the aims of such programs are reduced poverty and unemployment, reinforcement of local government and government transparency, improved governance, and strengthened communal leadership.

A combination of the two distinctions described above creates a typology that helps to position the various programs according to the level at which they seek to intervene (micro/macro) and the stage of radicalization at which they seek to intervene (de/counter/anti). An important distinction in this typology is that macro programs will always be about preventing radicalization, since they are aimed at a society or community in general, and not at individuals who are defined as at risk or are actively involved in the radicalization process.

| Micro | Macro | |||

| Deradicalization | Counter-radicalization | Anti-radicalization | ||

| Intervention level | Individual | Individual | Individual | Socioeconomic structure |

| Stage of intervention | Radicalization is complete | Radicalization is ongoing | Before radicalization | Before radicalization |

| Goals | Reverse the process | Stop the process | Prevent the process | Prevent the process |

| Examples | Prisoner rehabilitation programs, reintegration of former fighters into society | Hotline for cases of extremism, community policing programs, training for mental health professionals and social workers | Programs to reinforce identity and self-confidence, multicultural dialogue, education, and employment programs for young people | Reduce poverty, strengthen governance and transparency, build communal leadership |

For our purposes, the preventive programs are of particular importance, as is the need for rigorous Israeli research into the factors that accelerate radicalization processes in the particular local context. The findings could lead to insights about the potential of preventive programs to halt radicalization factors and even seek to establish elements that might drive processes of deradicalization. To the best of our knowledge (and after contacting a number of security authorities and the Prime Minister’s Office with a request for information), there is a considerable lack of preventive strategy in Israel, apart from some sporadic programs of limited scope. The result is a surprising and very problematic lacuna in Israel’s policy for dealing with political violence and terror. While this paper does not explore the reasons for this lacuna, it is possible to raise a number of assumptions: lack of awareness in the security system, or the habit of thinking about the struggle against terrorism solely in the framework of foiling and combat terms; fear of the possible interpretation of this approach in the political field (left wing elements might see this as “re-education,” while right wing elements would see it as an attempt to understand terrorists, treat their problems, and so on); or short-term thinking, while the struggle against radicalization usually achieves results in the medium to long term.

The Efficacy of Anti-Radicalization Programs

There is a wide range of programs to combat radicalization, aimed at different targets and with differing goals and methods. The activities promoted by the various programs include education and dialogue, study and vocational training, special training for professionals, communal involvement and empowerment, individual or family-based treatment, and tighter collaboration between authorities, as well as macro efforts to limit unemployment and improve living conditions. The question of efficacy is at the center of the debate among those engaged in the work. Since this is a new and developing field that has grown over the past two decades, approaches to the definition and measurement of program outcomes are constantly examined and refined.

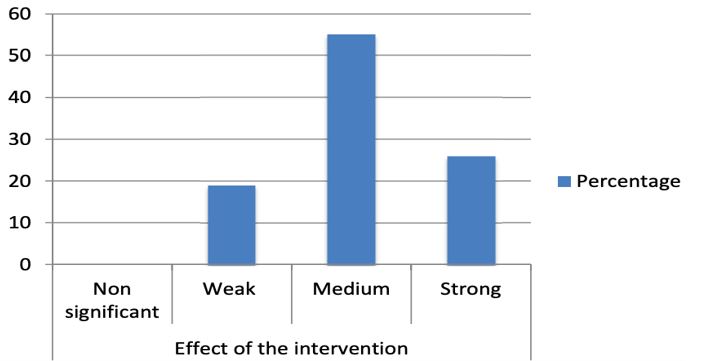

Nevertheless, researchers who have looked at the question of effectiveness agree that most of the programs manage to achieve their goals, at least partially, and many of them achieve a high level of success. For example, the 2014 study funded by the EU that assessed the results of 126 programs found that 26 percent had great impact, 55 percent had moderate impact, and 19 percent had little impact (Figure 1). None of the programs were assessed as having no impact whatsoever.

Figure 1: Efficacy of Programs to Combat Radicalization | Source: Impact Europe report, p. 62

Another study that was commissioned by the US administration in 2020 examined 30 programs from all over the world, aimed at a wide range of population groups. Of them, 15 were assessed as successful, five as having mixed results, and three as unsuccessful. According to the authors of the report, the features of successful programs included an element of reinforcing feelings of hope and meaning, a strengthened sense of community, personal attention, emphasis on relationships, and formulation of an individual list of priorities, as well as commitment and long term work with the target population.

Case Study I: The Danish Model

The Danish approach to countering radicalization is rooted in the idea that the state has two parallel functions: protecting society from terror attacks, and ensuring individual welfare. The approach is therefore based on three principles:

- Collaboration between the relevant authorities, including welfare, education, and health systems, the police, and intelligence and security mechanisms to provide an optimum response.

- Inclusion, defined as “meaningful participation in common cultural, social, and societal life”; the program focuses on rechanneling the personal and cultural motivations that lead to radicalization toward civil participation in a lawful way.

- A scientific and psychological basis; the program is run in collaboration with behavioral science departments, with ongoing research and evaluation.

The program draws its scientific basis from a crime prevention model known as the pyramid of prevention, based on many years of experience and development. At the base of the pyramid is the general level of prevention (anti-radicalization in the typology presented above). It is aimed at a wide population, particularly youth, and includes activities designed to strengthen their communal ties, build capabilities, and increase immunity. In this framework, representatives of the authorities initiate contacts and involvement with groups and communities that are not currently involved in any kind of extremism, but are at risk of such involvement in the future. Communal involvement includes raising awareness and special training to improve their general conditions at the communal and individual level.

At the center of the pyramid is the specific level of preventing escalation (counter-radicalization in the typology presented above). It is aimed at individuals and groups that are already identified with radical groups or undergoing processes of radicalization, but are not actively involved in violence. At this level, activities include strategies of removal from the radical environment, as well as work with families and the immediate social circle.

At the top of the pyramid is the level of objective—prevention of violent actions and events (de-radicalization in the typology presented above). It is aimed at individuals who have been identified as violent extremists, including, for example, those who are planning to travel to Syria or have returned from there. It includes programs for leaving organizations, rehabilitation, and re-integration into society.

In organizational terms, Denmark has created and dedicated an entity within a government ministry to handle all aspects of the counter-radicalization programs. It also implements an organizational model called infohouse: a specific address for every police district, which connects and coordinates between the police and local welfare agencies. This entity is responsible for assessing and handling information coming from the community, the authorities, or the police, coordinating between all the relevant services, finding preventive responses, and acting as a knowledge and training center. A school in the Danish town of Fredericia has also implemented a program to prevent extremism and segregation among children from different ethnic groups as a tool for preventing radicalization—a model that is fairly remote from the reality in Israeli education, apart from a few isolated enclaves and cases.

One of the most famous Danish programs was set up in Aarhus, and therefore named the Aarhus model. This model establishes infohouses, provides advice and training for professional entities, disseminates knowledge among the public, provides mentoring for individuals, offers counseling and rehabilitation for individuals who leave organizations, strengthens ties with communities and other elements who are in contact with individuals undergoing radicalization processes, offers giidance to parents, and sponsors workshops and dialogues for elementary and high school pupils.

The Aarhus program has seen impressive results: the number of local residents traveling to fight in Syria fell from 31 in 2013 to only one in 2014, after the program’s launch. Moreover, journalists collected testimony from individuals who participated in the program and said that it stopped them sinking into violent jihad. An NSI study for the US administration found that the program achieved mixed results.

Case Study II: Response to Youth at Risk in Antwerp

Belgium is the West European country with the largest number of Islamist radicals who fought in Syria. In the field of approaches to prevention of violence and involvement in terror and crime, there is extensive literature on the importance of creating responses for young people at critical transitional stages in their lives. Consequently, Belgian authorities have given top priority to programs designed to combat Islamist radicalization. In Antwerp, efforts focused on the integration of young people at risk of dropping out of school.

As with the Danish model, the Antwerp program is also based on close cooperation between the authorities. One of its pillars is the introduction of a network including local educational initiatives, schools, guidance centers for pupils, welfare and health services, the police and the Ministry of Justice, and the employment service. The program has an organizational structure called the central help desk, which is responsible for locating, monitoring, and developing responses for specific cases of youth at risk of dropping out or after dropout. The help desk is committed to provide a response for every case within a week of first receiving the information.

Another program, designed to prevent absence from school, has two components. The first consists of collecting comprehensive information from pupils, school principals, and staff about the sense of security in the school and its surroundings, using online questionnaires. The information is kept and analyzed anonymously by professionals in the municipality. The second component is a process of reflection and learning with the professionals about levels of absence from the school. Each year, the professional elements lead this process of reflection and learning in ten schools where the absence rate was low and the sense of security high, and in ten schools where the rate of absence had risen. In addition, any school can request such a process of reflection and learning during the year.

According to the Antwerp municipality, the programs have led to a significant decline in dropout and absence from schools in the city.

The Potential for Radicalization in Israel, and the Ability to Struggle Against It

The potential for recruiting Palestinian citizens of Israel to violent activity is relatively small, but still significant: according to a March 2022 survey conducted by the Accord Center at Hebrew University), 87 percent of Arab respondents said that Arab terrorists who were citizens of Israel did not represent them, 8 percent said that they represented them to a small degree, and 5 percent—to a large degree; this represents potential recruitment of tens of thousands. Over the years, studies have shown fluctuation between moderation and extremism among Arab citizens. For example, according to Prof. Sammy Smooha: “The proportion of Arabs who deny the right of the State of Israel to exist as a state was 20.5 percent in 1976, 6.8 percent in 1995 (during the second Rabin government, which is considered a golden age for Arab-Jewish relations), 11.2 percent in 2003, and 24.5 percent in 2012.” Although the fact of denying Israel’s right to exist is not evidence of a tendency to use political violence, these figures can be seen as a proxy indicator of rising and falling tendencies toward radicalization, so that it is not a static, unchanging picture. Former Knesset Member and diplomat Ruth Wasserman Lande contends that segregation, barriers to academic education, and lack of sufficient knowledge of Hebrew drive Arab citizens of Israel to study in Jordan and absorb culture and news mainly from foreign Arab channels, which can lead to radicalization. She contends how radicalization of Arabs in Israel could derive from social problems that must be addressed with more than only military tools. On the extreme Jewish right wing, a field study exposed the recruiting mechanisms of the Lehava Jewish supremacist organization, which focuses on youths from the margins of society and weak population groups, including formerly ultra-Orthodox and traditional Jews, and encourages hatred of Arabs. Dr. Asaf Malchi claims that the potential for recruitment to Lehava is increasing due an increased number of dropouts from ultra-Orthodox education. Extremist tendencies feed off each other, leading to further potential dangers among both Arabs and Jews.

The potential for radicalization in Israel, in the sense of a tendency to political violence, is bound up with structural aspects: the bloody and ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict; discrimination against the Arab minority in Israel and its exclusion from the political arena; the rule over Palestinians in the West Bank; and the intensity and deadliness of Palestinian terror, which often leads to extremism and sometimes violent responses from the Jewish side. These elements inevitably feed off each other. First, the ongoing conflict is based on the conflicting national narratives of two peoples and makes them more extreme: the dispossessed natives versus the people returning to its homeland and facing continuous unjustified violence. To this can be added many years of discrimination against the Arab minority in Israel, which can certainly contribute to radicalization, since, according to a study of political violence, discrimination is deemed a possible catalyst for violence. The discrimination penetrating socioeconomic aspects also leaves a mark: a relatively large percentage of young Arabs in Israel are poor, uneducated, unemployed, or working in menial labor with no employment stability, and this is potential for radicalization. It is therefore no surprise that according to documents exposed by Wikileaks in 2008, it appears that the GSS encouraged the Israeli government to improve Arab integration into the economy and make higher education and professional training more available to them, as a way of combating radicalization tendencies. There are also researchers such as Dr. Ephraim Lavie who see the relative exclusion of Arab citizens of Israel from the circles of political decision making—the non-inclusion of Arab parties in government for most of Israel’s existence—as a factor that contributes to a sense of marginality and exclusion, and therefore reinforces the tendency to choose force as a way of exerting influence.

In general, even outside the Israeli-Arab context, narrowing the scope for political influence tends to raise the rate of political violence, particularly when it is not extreme (apparently because this leaves room for organization and unionizing, as well as creating narratives of resistance and incitement to violence). Of course the broad Israeli-Palestinian conflict, friction with the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, and patterns of control or conduct toward them also affect Arab citizens of Israel and their attitudes to the state.

Radicalization in Israel and the Implications for National Security

Nonetheless, the fight against radicalization in Israel appears deficient: on the internet there is no open information about a comprehensive policy or significant programs of counter-radicalization, and an inquiry from the Initiative for National Security and Human Rights to the authorities for information about the implementation of such programs in Israel received no response. Nor does Israel appear in international surveys and comparative studies dealing with counter-radicalization programs in various countries worldwide. There are a few specific programs in Israel, such as a deradicalization program for security prisoners, i.e., those who have already participated in, assisted, or carried out violent actions. There is also a program in East Jerusalem that focuses on the transition to evidence-based policing, changes in the nature of police personnel, and rehabilitation of relations between the police and the population in the area. Improving the integration of Arabs in the economy and higher education as a way of countering radicalization is already a broader trend, although it presents as a limited reaction to a wave of polarization rather than part of an overall, orderly, and ongoing policy of de-radicalization; it remains to be seen to what extent this vision will be implemented. Apart from these specific programs, it appears there is no overall policy, and some of the tools deployed are regressive and problematic, both for combating radicalization and in terms of human rights principles. Due to the confidential nature of some of the entities responsible for security, it is difficult to obtain a complete picture and understand what attempts, if any, have been made to establish an inclusive strategy and programs to counter radicalization in Israel, what considerations underlie these attempts, and whether there was any intelligent debate on the subject.

From the viewpoint of national security, establishing an comprehensive strategy for combating radicalization will make it possible to relate to terrorism as a social phenomenon rather than only a security or military problem, so that the social factors that promote political violence can be thoroughly defined and a more comprehensive response provided. To illustrate, in many cases young people are exposed to propaganda that encourages radicalization that does not necessarily reach the criminal threshold of incitement or that is not necessarily spotted by counter-terror agencies. The struggle against radicalization proposes a response to these processes in the ideational sphere and in the realm of the social deprivation that fuels ideas that promote violence. In this context radicalization must be understood as a blow to national resilience, with terror and violence only the tip of the iceberg; there are also problems such as alienation from the state and hostility toward it, which may not reach the level of participation in violence, but are far broader than the narrow section of those who do participate, and are expressions of a situation that undermines social unity. This situation is naturally volatile, and at times of violent civilian eruption—during Operation Guardian of the Walls, for example—these alienated sections are liable to cross the line and join in spontaneous violence. “Classical” counter-terrorism efforts pay little attention to this despairing, angry, and alienated social faction with its explosive potential, in both the Jewish and the Arab populations.

Policy Recommendations

We propose establishing a government body to study radicalization in the Israeli context among various population groups, covering Jewish and Arab citizens of Israel. This body will also be responsible for developing programs and recommendations for policy in the field of combating radicalization. However, in view of criticisms from human rights organizations over the improper use of deradicalization programs—for example, the tracking and monitoring based on crude profiling of young Muslims in the British Prevent program—we recommend caution against practices that raise ethical problems and could also undermine the efficacy of deradicalization processes.

It is important to try to understand the dynamic and causes of radicalization, at the macro level (such as policies that elicit anger and radicalization), at the micro level (such as childhood trauma), and also at the local-communal (meso) level (such as interactive networks of incitement, inter-communal violence, and so on). In the framework of developing responses, policy changes at the macro level should be recommended and be transparently accessible to the public (providing they do not expose classified material), as well as programs for intervention at the local (meso) or individual (micro) level. The various programs should be based on models that have succeeded elsewhere, with an effort to adapt them to the local context, for example through a limited pilot program that is expanded based on results. Finally, distinct and tailored responses should be developed for different groups in Israel—Jewish and Arab.

A government body of this kind would provide a response to a significant lacuna in Israel’s security policy and would impact positively on national security. Such a response could also have a positive influence in the field of human rights, and thus, in turn, affect security and the horizons for reconciliation and strengthening social cohesion among the several ethno-national groups in the country.