Strategic Assessment

This article focuses on a particularly fateful day during the Yom Kippur War—the 1973 war between Israel to Egypt and Syria—Friday, October 12, 1973, the seventh day of the war, when some of the most important strategic dilemmas were deliberated. The article seeks to expand the existing literature about this particular day by analyzing the deliberations from a strategic perspective and through decision making theory, with an emphasis on three key issues. The first is the strategic confusion that existed among senior members of the Israeli defense establishment, once they understood that it was possible that the IDF would not be able to achieve its principal goal, namely, defeating the Egyptian army. Against this background, the article suggests that in retrospect, this singular moment in Israel’s military history, when the entire security doctrine was on the brink of collapse, accelerated and intensified the technological trajectory of the IDF force buildup after the war. Second, using tools taken from decision making theory, the article offers several reasons why one key proposal raised during discussions was ultimately rejected—the proposed alternative of waiting for the Egyptians to launch an offensive over the Sinai passes (the Mitla Pass and the Gidi Pass), which, in the end, is what happened. Third is an analysis of the decisions’ sensitivity—an important tool in the decision making process—to basic assumptions on which the decisions were based, such as the decreasing number of Air Force planes, or the intelligence report that arrived in the middle of the meeting of the war cabinet, which led to the immediate adjournment of that meeting. By highlighting these strategic angles, this article seeks to build a better understanding of the events of October 12, 1973, and to use it as a case study for the value of an analytical and strategic approach to understanding decision making in extreme conditions of war.

Keywords: Yom Kippur War, October 12, 1973, security doctrine, decision, decisive victory, decision making, technological superiority

The authors dedicate this article to the memory of Ehud Matania, the older brother of Eviatar Matania, who fought and was killed in Sinai on October 12, 1973, at the age 19.

Introduction

Israel suffered significant blows, failures, and uncertainty in the first days of the Yom Kippur War—the 1973 war between Israel to Egypt and Syria—with complex considerations raised among the country’s military, security, and political leaderships regarding decisions to be taken. Blocking the advance of Syrian troops on the Golan Heights on Monday, October 8, followed by their being pushed back two days later; launching a counteroffensive on the Syrian Golan Heights on October 11; and stabilizing the southern front—all these developments breathed new life in Israel’s military leadership. At the same time, however, Israel was running low on supplies, troops on the battlefield were exhausted, and the commander of the Air Force was warning that Israel’s aerial power was declining. In tandem, there were political negotiations with the United States regarding the imminent ceasefire discussions in the United Nations Security Council. All these developments converged on a day of fateful deliberations on the seventh day of the fighting, Friday, October 12, 1973, where the main focus fell on the strategic dilemma whether the IDF was capable of securing victory on the southern front and its operational alternatives.

The course of the discussions, the dilemmas facing the decision makers, and the available options on that day are not new. They have been studied and debated in the copious literature that has been published about the Yom Kippur War—literature that includes reference to October 12 as part of the course of the war as a whole. In addition, articles have been dedicated to that day or to part of it, such as that written by Shimon Golan (1992), which describes and analyzes the military and political decision making process on that day, or the article by Aharon Levran (2017), which focuses on the important intelligence report that arrived that day. Both articles adopt a historical perspective and analytical approach. Similarly, there is literature, primarily by Golan (2013), that refers to the minutes of the day’s various meetings, with the emphasis on providing public access to archival sources, as well as explaining and summarizing the contents.

This article seeks to add another layer to this literature and shed light on the decision making process on that day from a strategic perspective. In particular, it highlights three key issues in the context of that day. First, the article suggests that on October12, the principle of decisive victory as the foundation of Israel’s security doctrine—as had been entrenched during the 25 years since Israel’s establishment—was challenged. The inability to defeat the Egyptian army that was conveyed that day was a significant factor in shaping the IDF’s force buildup over the decades after the war, in terms of quantity, but especially in terms of unprecedented acceleration and intensification of the army’s technological force buildup, as this trajectory was less sensitive to the quantitative asymmetry between Israel and the Arab states.

Second is an examination of the decision making process on October 12, whereby several alternative courses of action were considered for achieving a decisive victory on the southern front. We focus on the option of waiting for the Egyptians to launch an offensive in the directions of the Sinai Peninsula passes (the Mitla Pass and the Gidi Pass). This alternative, which was ultimately realized in response to an Egyptian offensive, was not presented or considered with the same gravitas as the proactive crossing (without waiting for the Egyptian offensive); a number of reasons based on research in the psychology of decision making can explain this. Third is the sensitivity of the decisions to the fundamental assumptions underlying them, such as the decrease in the number of Air Force aircraft, or the intelligence report that arrived in the middle of the war cabinet meeting and led to its immediate cessation. Sensitivity analysis is an important tool in examining decision making processes and the decisions themselves, both in real time and in retrospect.

The article does not purport to recreate the mood among IDF commanders and leaders of the country on that seventh day of the war, nor does it attempt to stand in their shoes. The goal is far more modest: to analyze in retrospect the decision making process and deduce what the process looked like. In so doing, it hopes to add an additional layer to our understanding of the strategic decisions taken during the Yom Kippur War, with the emphasis on Friday, October 12, because of its singularity as a day of genuine concern about Israel’s ability to defeat its enemies and maintain is regional deterrence.

The methodology incorporates both primary and secondary sources regarding the deliberations of October 12, along with a strategic analysis of the events. The article begins by providing a concise background survey regarding the Yom Kippur War up to October 12, to show why so many strategic decisions converged on that day. It then describes the two main deliberations held one after the other on that day—the prolonged General Staff discussion, headed by IDF Chief of Staff David (Dado) Elazar, and the war cabinet discussion, headed by Prime Minister Golda Meir. It then analyzes the three issues mentioned above and provides a summary.

From the Outbreak of the War to the Morning of October 12

The Northern Front

The Yom Kippur war broke out on Saturday afternoon at 2 PM, October 6, 1973, on the holiest day of the year for Jews (Day of Atonement). The IDF was caught unprepared for the joint offensive launched by the Egyptian and Syrian militaries. The Syrian offensive lasted around 24 hours, during which Mount Hermon and central and southern parts of the Golan Heights were captured. One of the most significant decisions taken by the Chief of Staff was to redeploy the 146th Division, the only General Staff armored reserve division, that was under the command of Moshe (Musa) Peled, to join the campaign on the Golan Heights (Bartov, 1978, p. 52; Golan, 2013, p. 358). The division that joined the fighting on October 7 was, to a large extent, the tiebreaker that tipped the scales in the IDF’s favor on the Golan Heights. It allowed Israel to block the advance of the Syrian forces on the same day, and on the next day, October 8, to launch a counteroffensive. By the morning of October 10, through intensive fighting, the IDF managed to repel all the Syrian forces, with the exception of those on Mount Hermon, back to the Purple Line (the armistice line between Israel and Syria drawn following the Six Day War) (Golan, 2013, p. 641).

The IDF Chief of Staff arrived on October 10 at the headquarters of the army’s Northern Command, where he finalized details of the military’s offensive over the Purple Line, with one main thrust on the northern Golan Heights and on the foothills of the Hermon. The key considerations behind his decision were threefold. First, there was the deterrence consideration—signaling to the Arab armies and their leaders, and to the entire international community, that the IDF was intent on decisive and that the Arab armies should not sense Israeli weakness. The words “victory” and “deterrence” were intertwined throughout the discussions. The second consideration was the military-political consideration—defeating the Syrian army would likely lead Damascus to request a ceasefire, which, according to the Chief of Staff, the IDF needed, but preferred of course, for obvious reasons, that the request come from the Syrians, perhaps even a in joint request with Egypt. The third consideration was military in nature. The Chief of Staff wanted to thrust deep into Syrian territory before the Iraqi reinforcements arrived and while the Air Force was still able to provide close air support. In other words, the goal was to act before the Air Force was reduced to a size that it was no longer able to provide support for ground maneuvers (Bartov, 1978, pp. 154-162; Golan, 2013, pp. 658-689).

Prime Minister Meir accepted the Chief of Staff’s recommendation: “We authorize the IDF to launch a concentrated offensive tomorrow, to smash army divisions and to achieve total victory…The offensive seeks to take territory beyond the ceasefire line, to improve our positions and for the purposes of political negotiations” (Golan, 2001, p. 34). The next day, on October 11, the IDF launched its massive operation on the northern front, thrusting deep into Syrian territory.

On the morning of October 12, IDF forces were already on the Syrian portion of the Golan Heights, making steady progress, albeit slower than was expected. The IDF may have moved the war into enemy territory and secured a localized victory (with the exception of Mount Hermon, which was still in Syrian hands), but failed to secure the kind of outright victory over the Syrians that would have led to the collapse of their military.

The Southern Front

The situation on Israel’s southern front was different. Egyptian infantry, armed with anti-tank missiles, crossed the Suez Canal in boats, destroyed most of the fortifications that protected the eastern bank of the canal, and took control of the Bar-Lev (i.e., fortifications) Line. By the evening of Sunday, October 7, most of the troops from the Egyptian Second Army and Third Army were deployed on the eastern side of the Suez Canal, thereby controlling both banks. On the eastern bank, there were 1,000 Egyptian tanks and around 100,000 soldiers controlling territory several kilometers deep, up to 10 kilometers east of the canal (Bartov, 1978, p. 77; el-Shazly, 1987, pp. 163-170; Golan, 2013, pp. 455-457). The Egyptians stopped there, in accordance with their plan for the first stage of the war, but also because of the arrival at the front of two IDF reserve divisions (Golan, 2008, pp. 134-135).

The Egyptians were able to score such an impressive military achievement thanks to meticulous planning, a significant advantage in terms of troop numbers at the time of crossing the canal, localized superiority over Israeli armored forces by means of infantry forces armed with anti-tank missiles, and an array of surface-to-air missiles that prevented the Israeli Air Force from operating freely in the airspace over the canal (Shay, 1976).

In parallel to the counteroffensive on the northern front in the Golan Heights, the IDF launched a counteroffensive on the southern front on October 8, but it was not as successful as the one in the north. The entrenched Egyptian infantry, armed with anti-tank missiles, prevented Israeli forces from repelling the Egyptian bridgeheads. That was a second success for the Egyptians and a second failure for the IDF within two days. On Wednesday, October 10, Lt. Gen. (res.) Haim Bar-Lev, the former IDF Chief of Staff, took command in the south from the commander of the southern front Shmuel “Gorodish” Gonen, who was new in the position and, according to the Chief of Staff, was not yet experienced enough to manage the campaign (Golan, 2008, pp. 136-139).

In the following days until the morning of October 12, the situation on the southern front did not change significantly and the war turned static. The IDF learned the lessons of the failed counteroffensive and maintained a line of contact far from the Egyptian infantry. Tactical operations by the Egyptians to expand their bridgeheads were thwarted, entailing the loss of many of their men and tanks, while the IDF sustained far fewer causalities.

On the morning of October 12, the Israeli troops, on the one hand, were worn down after losing many soldiers and much equipment; they had no tanks or airplanes in reserve; and there were no reinforcements on the way. The IDF had already thrown everything it had into the campaign in terms of troops and equipment, and massive shipments of supplies requested from the United States had not yet arrived. On the other hand, after a week of intensive fighting, the IDF had no real shortage of ammunition, and its troops were able to launch an additional counteroffensive after the first one failed.

The Air Force

The Israeli Air Force showed a high level of preparedness when the war erupted: it defended Israeli airspace, attacked airborne enemy commando forces, engaged in dogfights, and launched bombing sorties on both fronts. The IDF in general—and the Chief of Staff in particular—saw the Air Force as the resource that could halt the enemies’ forces and stabilize Israel’s defensive lines until reserve forces arrived. Indeed, the Chief of Staff even referred to October 7 as “the Air Force’s day” (Golan, 2013, p. 356). However, due to fast-changing needs on both fronts, the Air Force did not work according to its plans and instead diverted its efforts from front to front. Consequently, alongside the success of some of the sorties, the Air Force did not destroy enemy missile batteries, which continued to down Israeli planes, neither did it obtain aerial superiority over the Suez Canal.

On the morning of October 12, Air Force Commander Maj. Gen. Benny Peled explained that Israel was approaching the level of 220 fighter planes—below which, he argued, the Air Force would no longer be able to support ground troops without putting Israeli airspace at risk. “Below this critical line of 200, 210, or 220 planes, give or take, I can no longer go on the offensive,” he said (Golan, 2013, p. 757). The Chief of Staff understood the warning and explained what it meant from his perspective: “In other words, we have to end the war by the 14th of the month, at the latest” (IDF and Defense Establishment Archive, 1975, Reel 18b).[1] Understanding the situation as presented by the commander of the Air Force was one of the main anchors underpinning the Chief of Staff's considerations regarding the decision making processes on that day.

The Diplomatic Front

Although the Yom Kippur War was waged between Israel and its Arab neighbors, it also reflected the struggle between the two blocs that existed at the time—the democratic West, under the leadership of the United States, and the Communist Eastern bloc, under the leadership of the Soviet Union. On October 10, the Soviets began to be concerned over an Israeli victory on the northern front and floated the idea of a ceasefire proposal between the sides, which would come into effect within a few days. On the afternoon of October 12, the Prime Minister's Office sent a message to the United States, saying “any delay would be good for us” (Telegram scans, 1973, p. 97). In other words, Israel was leaning toward accepting the ceasefire proposal, but asked the United States to delay implementation so that it could complete its offensive on the northern front, make territorial gains, and restore its deterrence. By the time Israeli leaders gathered for a series of discussions, negotiations over a ceasefire had gone into high gear and it appeared that the fighting would end on October 13 or 14, unless the Egyptians objected (Golan, 1992).

Decision Making Deliberations on Friday, October 12

The Decision Making Circles

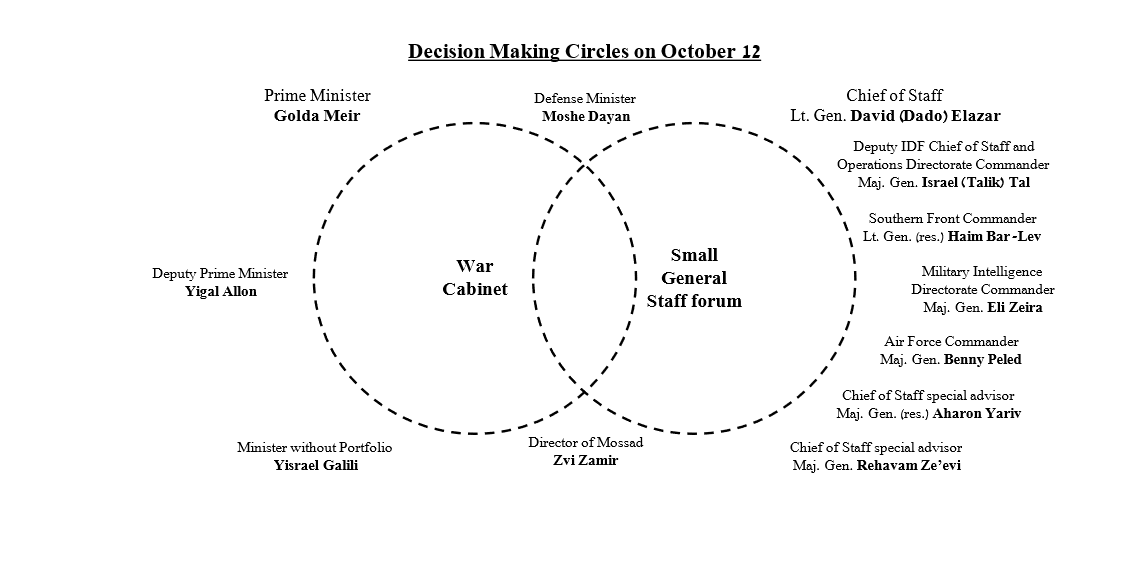

Two decision making circles that led Israel through the war were also the key forums for the decision making process on October 12 (Figure 1). The first and limited circle was headed by IDF Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Elazar and included Deputy Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Israel Tal, Military Intelligence Chief Maj. Gen. Eli Zeira, Air Force Commander Maj. Gen. Peled, and two of the Chief of Staff’s aides—Maj. Gen. (res.) and former Military Intelligence chief Aharon Yariv and Maj. Gen. Rehavam Ze’evi. On October 12, this forum was joined by the commander of the southern front, Lt. Gen. (res.) Haim Bar-Lev.

The second circle was “Golda’s kitchen cabinet,” also referred to as “the war cabinet,” comprising Prime Minister Meir and several of her ministers: Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Allon, Minister without Portfolio Yisrael Galili, and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan. In practice, this informal political-security cabinet was responsible for all decisions relating to the war on behalf of the government. These were in part symbiotic circles, because of Dayan’s presence in a large portion of the Chief of Staff’s decision making discussions (Golan, 2001, 2013, pp. 1267-1268).[2]

The Flow of the Deliberations on October 12

On the morning of Friday, October 12, the IDF in military terms was close to completing its operation on the northern front, and the Chief of Staff was in a position to make strategic-military decisions about the southern front. From his perspective, three clocks were ticking. First, in his view, the status quo on the southern front was counterproductive for the IDF; in other words, the IDF was worn down and did not have significant reserves, while the Egyptians were in a position to deploy fresh troops to combat, if necessary. The second clock was the erosion of the power of the Air Force, prompting its commander to warn that within a day or two, it would just be able to defend Israel’s airspace and would not be able to provide support to ground forces, which the Chief of Staff thought to be crucial. Finally, there was the political clock, the imminent ceasefire—but, rather absurdly, that clock was ticking in both directions. On the one hand, the Chief of Staff wanted a ceasefire, sooner rather than later, because his forces were fewer. On the other hand, he was worried that a ceasefire agreement would be reached while Egypt had the upper hand and before the IDF was able to record any significant achievements in its campaign against the Egyptian military. It was necessary to navigate between these two poles with military and diplomatic acrobatics and to ensure that the ceasefire agreement was reached at the best time for Israel.

In the early hours of the morning, the Chief of Staff began a series of consultations about what Israel’s next move should be on the southern front, on the assumption that “every day past the 14th of the month we will find ourselves in a worse situation, and every development on that front from the 14th of the month and onward could be to our detriment.” This working assumption led the Chief of Staff to the general conclusion that “we must do everything possible against Egypt to secure the best possible balance of power between us by the 14th of the month; I say the ‘best possible’ because I do not believe that we can reach the same situation with the Egyptians as we have with the Syrians” (IDF and Defense Establishment Archive, 1975, Reel 18b).

General Staff Deliberations

The question posed by the Chief of Staff to his generals was: “What do we have to do to secure a ceasefire,” adding, “We need this ceasefire. Now the question is how we get the ceasefire on the 14th of the month.”[3]

Bar-Lev, who came directly from the front, summed up the various operational alternatives. Regarding the possibility of driving Egyptian forces westward, from the eastern bank of the Suez Canal, he said, “clearing the canal is possible, [with] very many causalities…and our armored forces will be completely depleted.” Bar-Lev also presented the option of attacking Port Said, but added, “I do not think that Sadat would agree to a ceasefire if Port Said is taken.” The third possibility was to launch an operation to cross the canal with two divisions. Beyond the heavy price of establishing a bridgehead on the western bank of the canal, Bar-Lev noted that the operation was contingent on a single crossing bridge: “They can pound this single bridge; with artillery, they could by chance hit it with 10 shells while it is being dragged or when it’s here—and then there’s no crossing.” The fourth option was for Israeli forces to maintain their current positions and wait for an Egyptian attack over the passes, which would include its armored reserve forces. On this option, Bar-Lev said: “If we wait for them to attack, we could be waiting two weeks or a month, and in the meantime, there will be no ceasefire, and meanwhile every day we are attacked, every day we use ammunition, and this does not add to the morale of the troops.”

Of the four options, Bar-Lev preferred the more extensive crossing operation—not necessarily in the knowledge that it would achieve all expectations, but since he had ruled out the other options. Air Force Commander Peled came to a more simplistic but essentially similar conclusion: “Go in as hard as possible, as soon as possible.” Military Intelligence chief Zeira also thought that Israel should cross the canal: “The only option we have is to attack on the Egyptian front and cross the canal, and the only question I believe that we face today is: how to cross.”

Accordingly, there was almost complete unanimity among the top military echelon that the IDF should launch an offensive – preferably as comprehensive an operation to cross the Suez Canal as possible. Rather than helping the Chief of Staff formulate a recommendation for the political echelon, this wall-to-wall agreement made it more complicated. “I invented [the proposal] that we need to launch a massive offensive, so don’t try to persuade me to do it,” the Chief of Staff told his generals at one point. Later, he said “I would be happy, and you have no idea how happy, if you have better ideas than this one.”

Defense Minister Dayan joined the meeting chaired by the Chief of Staff, and after being briefed, said: “I am not enthusiastic about the idea.” Analyzing the proposal, Dayan concluded that while an attempt to cross the canal would change the military situation on the southern front, it would not resolve the Air Force’s problem, would not lead to the collapse of the Egyptian army, and would not help Israel secure a political victory. Moreover, Dayan believed that the presence of Israeli troops on the western bank of the Suez Canal would make it hard for Egypt to accept a ceasefire. However, since he was not familiar with all the military details, he did not reject the idea out of hand. Dayan asked for participants to separate the military and political considerations and said that it would take him time to study the military details before weighing the considerations.

After hearing the Defense Minister, the Chief of Staff summarized the symbiosis, as he saw it, between the political assessment and military operation, in a way that was telling about the complexity of the dilemma before him: “I have said that my assessment is contingent on the political assessment. My recommendation: I am prepared to attack only on condition that there is a chance of reaching a ceasefire within a very short period after the offensive. I do not believe that the IDF can attack, capture part of the bank, and remain in that position without a prolonged ceasefire. Unquestionably during this period there will be even more attrition and exhaustion and no possible recovery for force buildup. Therefore, I want to reach a final decision, and I will be willing in a discussion of this sort to present my final recommendation—but only in confrontation with the political assessment. If there is anyone who believes that it is unreasonable to achieve a complete ceasefire, then I do not recommend an offensive and there is no need for me to go down [to the Southern Command] to examine the plans. If anyone believes there is a chance, then I will go down this afternoon, examine and formulate plans, and then I will return with my military recommendation as to whether it is feasible or not from a military perspective.”

The War Cabinet Meeting

The war cabinet convened at 2:30 P.M., with the addition of the General Staff forum and the Director of the Mossad. After a short briefing on the state of Israeli forces on the southern front, the war cabinet was presented with the various operational alternatives on the Egyptian front. The leading proposal was an operation to cross the Suez Canal with two divisions, creating a bridgehead on the western bank of the canal. The other options were presented by Bar-Lev, both of them in negative fashion: The IDF can repel Egyptian troops from the eastern bank of the canal, but at the cost of a high number of casualties—so much so that the IDF would no longer have a strike force on the southern front capable of launching an attack, while the Egyptians would still have significant reserves. Similarly, Bar-Lev ruled out another non-offensive alternative, which was to withdraw from the line of contact to better defensive positions in the passes. He did not think this would advance a ceasefire, reduce clashes with the Egyptian forces, or encourage them to attack the passes—a situation in which Bar-Lev believed Israel would have the upper hand (Consultation, October 12, 1973). Consequently, the military leadership brought the political echelon just one realistic military option, an option that the Chief of Staff wanted to make contingent on an assessment of its possible political ramifications.

Ministers Galili and Allon pressed the generals and tried to ascertain what their recommendation would be if it were possible to disconnect the military considerations from the political considerations. In this respect, the two ministers adopted a stance similar to Dayan’s previous line: political considerations must be separated from military, operational considerations. Shimon Golan summed it up well: “The political leadership believed that the Chief of Staff should not condition the operation to cross the Suez Canal on whether it would contribute to the ceasefire efforts, and that he should restrict himself to purely military considerations. His position, which tied the two aspects together, created a dilemma” (Golan, 1992, p. 11).

Especially interesting at that meeting are the comments of deputy Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Tal. He refined the dilemma and focused on the Air Force, since the state of the Air Force determined the military timetable. An operation to cross the canal, he believed, would not ensure that the Egyptians request a ceasefire. Moreover, even success on the Syrian front did not guarantee that Damascus would seek a ceasefire. Therefore, the demand that the Air Force assist ground forces remained. The obvious conclusion, therefore, is that the declining state of the Air Force could not be the main consideration when debating whether to cross the Suez Canal. He added that there was much uncertainty regarding the next military operation that the Egyptians were planning to launch (Consultation, October 12, 1973).

The Intelligence Report and the End of the Deliberation

Before the deputy Chief of Staff had finished his comments and before the ministers voiced their opinions, the Director of the Mossad was called outside, and when he returned, he stopped the discussion and read a report out loud he had just received about an Egyptian plan to deploy paratroopers on October 13 or 14, in order to launch an offensive against the Sinai passes (Levran, 2017).

His interlocutors immediately understood the significance. The military commanders were well aware of the Egyptians’ war plans: after a week of consolidation at the bridgeheads, the Egyptian army would enter another stage of fighting, during which it would try, with a combination of paratroopers and armored divisions—including the reserves remaining on the west bank of the Suez Canal—to capture the Sinai passes. Those present, therefore, expected two developments. The first was that the Egyptians would engage in an armored battle in open ground, in which the IDF would have a decisive advantage and would be expected to destroy many Egyptian forces, or, as the deputy IDF Chief of Staff said immediately upon hearing the news: “There will be 900 [Egyptians tanks] and we will have 700. It is inconceivable that the Israeli armored forces, with that kind of troop balance, while it is waiting for their armored forces, and such an excellent Air Force, which would help to land a massive blow of this kind—it is inconceivable that, as a result, hundreds of tanks will not be blown up and the battlefield set ablaze. It would be a dramatic and sensational blow, the likes of which we have not seen, and it will take the wind out of the sails of the Egyptian offensive and burst their balloon, on condition that we prepare for this battle” (Consultation, October 12, 1973, p. 17). The second development was that an Egyptian offensive, as senior IDF officers understood it, would leave the western bank of the Suez Canal without effective defense against the Israeli forces that may cross the canal.

If the scenario suggested by the intelligence report came to pass, the situation the IDF had longed for would also come true: a battle between armored divisions in open ground, in which the IDF would wield a significant advantage. From that moment on, the dilemma was resolved. The confusion was dispelled, or, as the Prime Minister put it: “Well, I understand that Zvika has brought the discussion to an end.” The Chief of Staff returned to General Staff headquarters and said: “Now I know what to do. We will prepare well; we will repel the advance of the Egyptian armored divisions on October 13-14, and we will hit them hard. After that, we will cross the canal” (Levran, 2017, p. 32).

In Retrospect: A Strategic Analysis of the Decision Making Process

The Principal Dilemma: The Challenge to the Security Doctrine and the Strategic Turning Point

October 12 was entirely different from every other day of the war. During the first days of the war, the IDF was shell shocked and preoccupied with efforts to repel the enemy, and after October 12, the momentum was in Israel’s favor (despite the challenges). Between October 10 and 12, the political and military leadership was at the junction between defensive action and offensive action. The IDF was already back on its feet and could be sent on the offensive to achieve military and political gains, as occurred with great success on the northern front.

On October 12, Israel’s leaders were forced to decide on an offensive on the southern front, but without an alternative that the IDF would, to a high degree of certainty, secure decisive victory, as dictated by the country’s security doctrine. Instead, they were presented with scenarios that, if they were successful, could at best improve the situation on the front or even lead to a ceasefire, which, since left with no other real choice, had become their main objective, but would not necessarily secure victory.

To be sure, some researchers believe that already by October 8, after the failure of the counteroffensive in the south, some senior members of the security establishment began to understand that Israel would not be capable of defeating the Egyptians (Milstein, 1993, 2022); this would be reflected later, in advance of the discussions on October 12. We do not take issue with this argument, primarily because even victorious armies lose battles sometimes, and we should be wary of extrapolating anything from one failure with regard to the doctrine in its entirety—especially since in tandem, the IDF was recording success in its offensive in Syria, which changed the course of the war. In addition, our focus is on the strategic decision making processes about the various strategic alternatives themselves—processes that were clearly evident in the discussions between members of the General Staff and the political echelon—and not the processes that led them to their conclusions, recommendations, and decisions.

Therefore, we see the deliberations held on Friday, October 12, as a series of strategic discussions, during which, for the first time in the 25 years of the State of Israel’s existence, Israel found itself in a situation whereby one of the key elements of its security doctrine—achieving a decisive victory over the enemy in every round of combat—was about to be punctured, compounded by a potentially significant blow to Israel’s deterrence.

The fundamental assumption underlying Israel’s security doctrine is that the country will always face inherent asymmetry vis-à-vis the other countries in the region—in terms of population, area, strategic depth, and resources. The asymmetry forces Israel to formulate a singular security doctrine in order to survive in a hostile region. This understanding led to what is known as Israel’s “trifold defense doctrine.” The first of the three pillars is the ability to decisively defeat the enemy any time it attacks, and in so doing, leave it incapable of continuing its offensive and needing a ceasefire. This pillar has immediate ramifications for Israel’s force buildup and operation. This includes an emphasis on a powerful Air Force as a technology-based strategic branch of the military, which allows for swift action even without early warning, as well as an emphasis on rapid offensive maneuvers inside enemy territory. In order to be able to call up enough reserve forces to carry out this decisive military operation, Israel needs timely intelligence warnings. Since even the decisive defeat of the enemy in a battle cannot bring about the total surrender of the enemy, due to the extreme asymmetry between Israel and the Arab states, it can only ever serve as a momentary and localized victory. Repeated decisive victories will deter the enemy from any further attempts to destroy the State of Israel, and (accumulated) deterrence will be achieved after a number of rounds of conflict (“theory of rounds”) (Ben-Israel, 2013; Matania & Bachrach, 2023). [4]

The early warning pillar was found wanting at the very start of the war. The IDF was forced to repel Egyptian and Syrian troops with just its standing army and support of the Air Force until the reserve forces arrived. As a result, Israel suffered the loss of much territory on the Golan Heights, the breach of the Bar-Lev line and the Suez Canal, and the establishment of Egyptian bridgeheads close to the canal. Moreover, the absence of early warning also affected the Air Force, which sustained many losses when it was forced to operate in a more frenetic and less ordered manner than it had planned.

On October 12, however, the principle of decisive victory, one of the most important elements of the defense doctrine, was undermined and faced significant difficulties. For all intents and purposes, on that day the IDF Chief of Staff instilled the awareness that the total defeat of the enemy armies was not the primary goal, since there was a very high probability that it could not be achieved. Instead, he proposed military moves that entailed no small degree of risk, which he believed would near Israel as close as possible to the point of political negotiations and a ceasefire, not out of loss, but also not in the aftermath of a decisive victory in combat. The option that the Chief of Staff proposed, which stemmed both from political logic (the desire for a ceasefire) and military rationale, was to cross the Suez Canal. This was not in order to achieve the decisive and final victory that the country’s political leaders sought, but as the best alternative at that time, as he told the war cabinet: “It seems to me that one of the criteria for carrying out an attack tomorrow is whether it increases the chances of a ceasefire…This, for me, is almost the main criterion for carrying out this offensive…I must work on the assumption that this operation will be a major blow to the Egyptians, but I am not certain that we can lead to the collapse of their army” (Consultation, October 12, 1973, p. 2).

In our eyes, the Chief of Staff’s analysis of the situation prompted his recommendation departing from the rationale behind the offensive in Syria—attacking the Syrian Golan in order to capture territory while threatening Damascus and the destruction of the Syrian army, that is, securing an outright victory that would restore and bolster deterrence. In contrast, on the southern front, against the Egyptian army, the Chief of Staff officially abandoned the pillar of total victory and, as a result, the principle of cumulative deterrence underlying the security concept. This deterrence was supposed to be created after repeated victories over the enemy in each conflict. The inability to decisively defeat the enemy clearly has an immediate impact on Israel’s cumulative deterrence over the years against all its enemies, who could come to believe that Israel is a temporary phenomenon. Accordingly, failure to secure decisive victories could lead to the collapse of the entire security doctrine.

In other words, on October 12, the security doctrine that Israel had embraced until that moment experienced significant difficulties and reached an impasse; some people would say that Israel’s security doctrine collapsed on that day. This was an unparalleled situation, not just in terms of the Yom Kippur War, but in terms of the history of the State of Israel. Until that point the security doctrine had never faced such a massive rupture—and it never would again. That is: On the morning and in the afternoon of October 12, there was severe strategic confusion among senior IDF commanders and members of the Israeli government as to whether the Israeli military was able to fulfill its role in the country’s security doctrine. In the early afternoon hours, after the arrival of the intelligence report, the confusion was replaced with an understanding that the tables were about to be turned. This eventually happened after 12 days of intense fighting, during which total victory was achieved and the security concept was reaffirmed. The phrase “strategic confusion” does not mean here surprise, difficulty, catastrophe, and so on; rather, it means helplessness in light of a situation whereby the system’s foundational principles are collapsing. For the leaders seeking to navigate the stormy waters of that war, the strategic compass, the principle of decisive victory, was no longer of use.[5]

From a historical perspective, the strategic confusion was not merely a singular event that had no influence on Israeli decision makers. Despite the success of the operation to cross the Suez Canal after the launch of the Egyptian offensive and the achievement of clear military victory on the southern front, the nadir reached during the October 12 deliberations is also the foundation for the turning point in Israel’s force buildup after the war. Even if the outcome of the war merely strengthened Israel’s cumulative deterrence vis-à-vis the Arab states—i.e., Israel cannot be destroyed and cannot be defeated in localized combat, exactly because of the IDF’s ability to record decisive victories notwithstanding the challenging opening conditions: “Our military situation on October 24 was at an all-time nadir” (el-Shazly, 1987, p. 196)—the view was very different from the Israeli side, and Israeli leaders did not bask in the glory of a military victory.

In other words: the helplessness when it came to the IDF’s inability to secure a decisive victory and the ramifications thereof, as experienced first-hand by Israeli leaders on October 12, left a weighty concern about this ability in the future if Israel were ever to find itself in a similar situation. This is clearly evident in the changes to Israel’s force buildup in the years after the Yom Kippur War (Bar-Yosef, 2023).

The October 12 deliberations, therefore, reflect an important turning point in implementation of Israel’s security doctrine, with two force buildup vectors. The first was to increase the size of the IDF by almost doubling the number of troops. This move increased defense spending and severely damaged the Israeli economy; in retrospect, many people say it was unnecessary and question the learning process behind it (Bar-Yosef, 2023). After a decade or so, following the peace accord with Egypt and the First Lebanon War, Israel began to reverse this process, and instead focused on the buildup of the second force—the technology-based force.

The first signs that the IDF was turning in a technological direction were visible even before the Yom Kippur War and were already evident in the writings of David Ben-Gurion. Science and technology, he believed, alongside elements such as morality and the capabilities of soldiers, especially the commanders, were the key factors in establishing a decisive qualitative advantage to offset the numerical asymmetry. They formed the foundation of the national security doctrine (Ben-Israel, 2013, pp. 51-58).

Indeed, Israel’s technological-military capabilities were not born in a single day. The first steps that were taken in the first two decades of the state’s independence were vitally important to build the ethos, the intention, the system, and the foundation that would eventually turn the IDF into an army for which technology was a key factor. Nevertheless, these steps were still a long way from creation of cutting-edge capabilities in terms of research and development (Mardor, 1981, p. 75). Accordingly, early in its history, the IDF was not a military that relied on very different technologies than those employed by its enemies and did not enjoy technological superiority. This was also the case during the Yom Kippur War. The IDF’s main advantages were the quality of its fighting force and its commanders, and not any significant technological advantage (Finkel, 2020).

After the war, however, technology became a key issue for the IDF, with the effort to obtain a qualitative edge leaning increasingly and to an unprecedented extent toward technology and the ability to use it (Lifshitz, 2011, p. 10; Matania, 2022; Finkel & Friedman, 2016). Over the years, technology came to be seen not only in the direct context of obtaining a tactical advantage, but also as linked to conceptual operational changes implemented to obtain the strategic upper hand (Sharvit, 2004). Moreover, it began to appear consistently, clearly, and centrally in the IDF’s official literature (for example, Kochavi, 2020) and in writing by researchers on Israel’s security doctrine and force buildup (for example, Eilam, 2009, pp. 497-508; Amidror, 2020).

One example of the direct influence of the Yom Kippur War on this process was the establishment in 1979 of the Talpiot program to provide world-class training to Israel’s scientific and technological workforce for defense research and development, with special emphasis on people capable of operating in both the realm of operational problems and in the world of providing the technological solution, all at the same time (Matania, 2022). This is a direct lesson from the Yom Kippur War, as suggested by two professors from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Felix Dothan and Shaul Yatziv (1974): “The military and political trends in the short and long term appear bleak. This raises the question: what can be done to take action against these trends, and how the IDF's force can be greatly strengthened…We propose a concentrated and systematic effort to invent and develop new weapons…with ‘new’ defined as what is not used by other armies.” They went on to propose what would become the Talpiot program: “A necessary condition for the success of such a program is the creation of a team of creative people, who ‘spawn’ the ideas and afterwards translate them [into practice].”

Another example is the development of the Air Force’s extraordinary technological and operational capabilities in dealing with surface-to-air missiles, as exemplified by Operation Mole Cricket 19 during the First Lebanon War in 1982. This unique capability, which was developed as a partnership between the Air Force and Israel’s defense industry, changed the reality that the Air Force faced during the Yom Kippur War, as it sought to deal with surface-to-air missiles (Finkel, 2019). Not only was this the development of a specific capability that restored the Air Force’s superiority in the face of anti-aircraft weapons for several decades (Lorber, 2022); it also ushered in an age in which technology was not just a tactical force multiplier, but part of a comprehensive change in doctrine aimed at securing techno-operational superiority (Sharvit, 2004). This was also part of Israel’s revolution in military affairs, which later became a comprehensive doctrine for the United States.

Another example of processes from the 1980s that evolved from developments that began even before the Yom Kippur War but were accelerated because of it, is the deliberate and planned restructuring of the country’s defense industry into an industry with impressive cutting-edge exports and world-class expertise. This would allow these industries to grow and progress far beyond their size relative to the size of the IDF, thereby providing the IDF with R&D and arms and ammunition that are at the very center of the quest for technological superiority (Rubin, 2018).

Therefore, the shift toward relying on technology as an element that builds quality and leads to technological superiority in combat, which is an essential element in reaching military superiority, was accelerated as a result of the Yom Kippur War in an unprecedented manner, in order to allow the IDF to secure a decisive victory under any circumstances. Decisive victories no longer relied exclusively on “our best people” in the battlefield or on the inferior capabilities of the enemy; rather, there was an effort to focus on elite human qualities (“our other best people”) in the creation of advanced technology as a self-perpetuating cycle that grows stronger over the years (Matania, 2022).

This process created significant technological superiority for the IDF on the conventional battleground—an advantage that is less sensitive to the numerical asymmetry between Israel and the other countries of the region, and accordingly provides a suitable answer to the IDF’s need to achieve a decisive victory against the numbers it faces. Decisive victories are no longer based primarily on efforts to narrow the numerical gap using a service model that has a standing army and reserves, as well as huge budgets for the procurement of arms and ammunition, but also on an orthogonal direction to those efforts.

The question is rightly asked why we ascribe the accelerated turn toward technology to the events of October 12, rather than to the Yom Kippur War as an entire single event. However, this is not our intention, nor do we argue that the decision to move in this direction was taken on that day. We also do not suggest that other events during the war did not contribute to the decision. What we do assert is that October 12 demonstrates best the strategic confusion over the inability to achieve a decisive victory, and the strategic helplessness during the war, and, as such, it was a turning point. Without that specific concern over Israel’s ability to secure a decisive victory and everything that this failure entails, the significant post-war developments of the IDF’s force buildup would not have happened.

In other words: it is possible that had the IDF’s counteroffensive on the southern front on October 8 been successful, as was the counteroffensive on the northern front, or had the Chief of Staff been presented with better options than an attempt to secure a decisive victory in the south (options that would have turned the tables after October 12 without reaching a situation in which he said that the IDF could not win a decisive victory), the war might have looked different from the Six Day War, but might not have spurred such an accelerated and significant revolution in force buildup. These changes were primarily the result of losing the ability to win a decisive victory, as was stated and understood on that day. Therefore, it is appropriate for us to ascribe the entire force buildup effort, quantitative and technological, to the deliberations of Friday, October 12, which reflected the lowest strategic and military point that Israel had experienced until that point and, in our view, ever since—up until October 7, 2023.

The Overlooked Alternative

The difficult war cabinet meeting, laden with the weighty dilemma, ended at once when the intelligence report arrived indicating that Egypt was planning Stage 3 of its offensive—an attempt to break out of the bridgeheads, capture the passes in the Sinai Peninsula, and stand to their east (on the planned Egyptian offensive, see, for example, Shai, 1976). At that moment, it was clear to all what the correct course of action was: wait for the Egyptian army, set ambushes, destroy their forces, and then launch an offensive over the Suez Canal in between the two Egyptian armies, taking advantage of the fact that the Egyptian forces were dealt a blow that would stun them and fewer troops would be stationed on the western side of the Suez Canal to halt the Israeli crossing. That was clearly the best option presented that day—and it even resolved some of the difficult dilemmas that Israeli decision makers were facing.

How, then, is it that the option of waiting, which is the alternative that was selected in the end, was not discussed in depth? It was mentioned, primarily at the start of the discussions, but was not put properly on the table at any time—not even to reject it and choose another alternative. The IDF commanders recognized it and hoped for it, since it was without doubt the best option for the Israeli military at that moment. However, as indicated below, it was ruled out almost without second thought, while other options were discussed at length.

At the start of the war cabinet meeting on October 12, the Chief of Staff raised the possibility that the Egyptians would attack, but he was consistent in his assumption that he had at most two days before the IDF attacked the Egyptians (because of forces’ erosion, the state of the Air Force, and the political clock), until the night of October 13. In other words, according to the Chief of Staff, an Egyptian offensive was a variable that could impact the nature of the attack initiated by the IDF, but waiting for an Egyptian offensive was not seen as a viable alternative compared to an initiated Israeli offensive—neither passive waiting nor waiting while taking steps in attempt to lure the Egyptians into expanding the bridgeheads eastward.

Bar-Lev, the commander of the southern front, did mention at the meeting the option of waiting for the Egyptians, but he portrayed it as defense for the sake of defense, not defense before offense. Therefore, he concluded that waiting for an Egyptian offensive would not “knock the course of the war off balance” (Consultations, October 12, 1973, p. 8)

At an assessment meeting with the Chief of Staff that morning, the head of Military Intelligence addressed the chances that the Egyptians would launch an offensive toward the passes, saying: “Once again, we have seen no signs of preparations to move their armored divisions. I have no reason to change my assessment from yesterday that the chances that they will move them are not above 50 [percent], and it is possible that they will never move them” (IDF and Security Establishment Archive, 1875, Reel 18B). This assessment was not challenged in any significant way, notwithstanding the additional information that was available to IDF commanders and could have been used to formulate an assessment of when the Egyptians would launch their offensive.

For example, army officers were well aware of the Egyptian war plan to launch an offensive after around seven days of operational pause, from the moment that they established their presence on the bridgeheads on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal.[6] Similarly, in the October 12 discussions, there is no evidence of an inter-front analysis—in other words, an analysis of how the Israeli military’s progress toward Damascus on the northern front might have impacted the Egyptian front. It was conceivable that Egypt would come to the aid of its ally and try to halt Israeli progress in Syria by executing the next stage of its Siani offensive. Moreover, one could have expected Israeli leaders to think of ways to lure the Egyptians into attacking the passes, if they viewed that as an optimal scenario. That is, they did not have to accept the lack of certainty over the timing of an Egyptian offensive as an edict that could not be challenged.

There are a number of reasons why this alternative was not raised as one of the main options, stemming from the nature of the alternative on the one hand and the way in which the decision making process was conducted on the other. They are important not only from a historical, analytical perspective, but precisely to study and learn lessons for the future with regard to strategic decision making processes. The reasons offered here are based on the psychology of decision making and do not rule out the possibility that the generals, from their perspective, examined this option thoroughly and chose to reject it for pertinent reasons. Nevertheless, they highlight the possibility that the process and the nature of the other alternatives were highly influential in the disregard of this option—or explain why it was not discussed in depth.

The first reason we propose is that the Chief of Staff and his generals were anchored in thinking in terms of a war that would last only a few days. Anchoring is a concept in decision making that suggests that whether they are aware of it or not, decision makers are anchored to numbers or to rhetoric that influence their assessments (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Sometime, even mentioning an issue in terms of days rather than weeks can influence the assessment (Yaffe & Matania, 2011). The option of waiting might perhaps have been implementable only a day or two after the deliberations, while the Chief of Staff was not willing to postpone the offensive until a later date, mainly because of the state of the Air Force.

While the Chief of Staff may have been right, it is also possible that he thought in terms of days because the Six Day War was his starting point and his point of reference for intensive combat (unlike the War of Attrition). In other words, the Six Day War still anchored his conception of the possible length of the war. In practice, the Yom Kippur War lasted for almost three weeks and not for a few days. The IDF withstood the attacks and the Chief of Staff led the army successfully even before the supplies from the United States began to arrive, from the second week of the war. Thus it is possible that his rush to make a decision and to act—which stemmed from the three swords he felt were hanging over his head: the state of the Air Force, the state of the ground forces, and the timing of a ceasefire—led to the anchoring of his thought process in a scale of days. This was the opposite of how the Defense Minister, Dayan, for example, viewed the timetable. He told Bar-Lev: “The Suez Canal is not the Temple Mount nor the Golan Heights…It does not endanger the State of Israel and it’s not like the Golan Heights, where, if we don’t do something within two days...what can happen in two days?” (IDF and Defense Establishment Archive, 1975, Reel 20).

The second explanation is also connected to the nature of the alternatives and stems from status quo bias, an effect that suggests that decision makers prefer to continue with their current course of action, i.e., the status quo. That is, they cling to the traditional or existing alternative, even if it is not the course of action they would have chosen without the option of the status quo (Kahneman et al., 1991). Somewhat paradoxically, even though none of the various alternatives debated were already existent, in the case of the southern front the option that best suited the IDF, which in principle was the default option of the IDF as a proactive army, was to cross the canal and not to wait—something that also fit very well with the Chief of Staff’s assessment regarding the swords hanging over his head. The passivity of waiting versus the proactivity of attacking: a military accustomed to managing and controlling the battlefield in almost every incident and war thus far cannot simply wait for the enemy to make a mistake before acting. That was against everything that the IDF knew and upon which it was driven. Hence, the “status quo” for the IDF was to attack proactively, and not to wait passively.

Compounding this is the uncertainty or the risk involved in waiting for the Egyptian offensive, which might not happen at all. Nevertheless, one should keep in mind that the alternative of crossing the canal also entailed risks. Different risks, certainly, but risks nonetheless: the Egyptian units that were still positioned on both banks of the Suez Canal could, according to assessments, cut off the crossing corridor on the eastern side of the canal or block IDF troops on the western side. In other words, the proactive attack alternative suggested also entailed considerable risks, that the deputy Chief of Staff, for example, believed would be wrong to incur.

Thus both options contained an element of uncertainty and risk, albeit in different ways: one, gambling on an Egyptian decision to launch the next stage of their offensive relatively soon, and the other, gambling on the ability of IDF forces to execute the plan to cross the Suez Canal successfully—a risk that depends not only on the capabilities of Israeli forces, but also on those of the Egyptian enemy (albeit to a lesser extent than with Egyptian decisions). The difference between the two types of risk is clear and it was, inter alia, at the heart of the decision to opt for the option of crossing the canal: with the option of waiting, the risk appears to be one of military passivity, which is not appropriate for an army like the IDF that aspires to decisive victories and is not its usual modus operandi (not its familiar status quo). With the option of crossing the Suez Canal, however, the risk is considered legitimate in terms of military decisions taken throughout history and is also seen as proactive, which matches the culture of the IDF.

The third explanation proposed is based on regret theory. According to this theory, and as has been borne out by experiments, one of the considerations of decision makers when choosing between various courses of action is, in simple terms, to what extent they might come to regret their decision if, in the end, it would have been preferable for them to choose a different option that would have yielded a far better outcome. The key point here is that the choice is not made according to the optimum outcome of the various options at the moment of the decision taking, but rather according to the degree of possible regret each would engender (if they were to fail), according to the level of potential regret one ascribes to each option in the first place, and to its minimization (French, 1988, pp. 16-17; Loomes & Sugden, 1982).

In the case of waiting for an Egyptian offensive that never comes, the regret would be severe. This is especially true for an army like the IDF, which is used to being proactive, taking the battle into the enemy’s territory, eliminating enemy formations, or in short: reaching a decisive victory over the enemy. Even today, there are many people who urge the IDF to secure a “decisive victory,” even though it is far from clear what that is. Regret over superfluous waiting could be immense, especially when weighed against the alternative of crossing the Suez Canal: during the time that was wasted, Israeli troops, especially the Air Force, were worn down even further, the apparently imminent ceasefire became ever closer, and it was conceivable that Israel would no longer be able to choose the alternative of crossing the Suez Canal.

In contrast, in the event of an attempted crossing that did not fulfill its mission, IDF commanders would be able to say to themselves and to others, with a great degree of justification, that they did their best. Any comparison would only be between the other proactive options, and the risk they took would be clearly evident. The option of waiting would not be on the “regret table” at all in this case, as Bar-Lev himself said: “In the case of total success, the situation will be fine, while ‘if our belief and faith does not come true’ the situation will be as it is now, with one difference – the IDF did the best it could; if it continues to wait, it will leave the enemy with the choice of when to launch an offensive—and it will choose the best moment from its perspective” (Golan, 2013, p. 772).

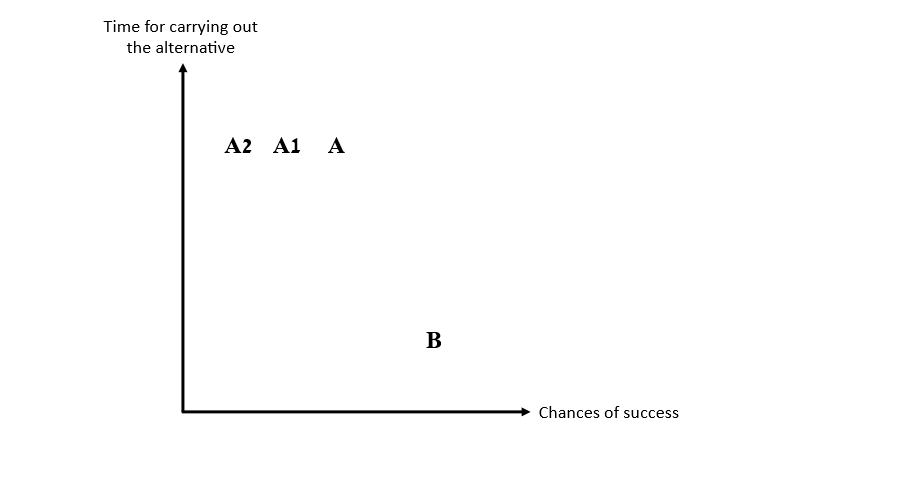

Another interesting possible explanation of the decision to ignore the option of waiting for an Egyptian offensive almost totally stems not from that option itself, but from the general decision making process between the two alternatives, each of which had a clear advantage over the other on one axis and a clear disadvantage on the other axis (Figure 2). The option of crossing the canal (A) performed well on the time axis but was weaker on the axis of chances of success in achieving its goals with a high degree of certainty. Option B was the option of waiting for the Egyptians to launch an offensive, which was very strong in terms of achieving its goals (as indeed happened), but very problematic in terms of the time dimension when it was under consideration.

Psychology research in the field of decision making that examined the choice between weak and strong alternatives on two axes that cannot be easily compared, discovered that the decision is influenced by the starting point of the decision making process and by the other alternatives on the table (Kahneman et al., 1991; Tversky & Kahneman, 1991). Inter alia, when alternative options are proposed for just one side of the equation—for example, Options A1 and A2, which are very close to the original Option A—without similar and approximate alternatives to Option B, there is a marked increase in the chances that Option A will be selected, rather than Option B. This is because the comparison between those new options presented, A1 or A2, and the original option is easy. They resemble each other (and lie, more or less, on the same axis), so it is relatively easy to decide between them. The important point here is that that the very existence of Options A1 and A2, and the ability to compare them to Option A, even if they are inferior to it and perhaps not even relevant, can often draw the choice toward the original Option A, while ignoring Option B, which did not have anything to be compared to. Decision makers are not aware of the subconscious process that persuades them to prefer Option A simply because Options A1 and A2 exist. The opposite is also true, of course: were similar options to Option B presented, there would be a greater chance that Option B and not Option A would be chosen, simply because there were similar options to Option B and, again, decision makers would not be aware of this bias (Shafir et al., 1993).

This, more or less, is what happened during the discussion on October 12: While the option of crossing the Suez Canal with two divisions, thrusting in between the two Egyptian armies (henceforth, Option A), was compared to the option of attacking Port Said (A1) or attempting to repel the Egyptians from the eastern bank of the canal to the western bank (A2), the option of waiting for the Egyptians to launch an offensive (henceforth Option B) stood alone. It is entirely possible that the very existence of a number of proactive alternatives in addition to the option of crossing the Suez Canal, even though they were considered inferior to that option, and the ease of comparison between them, as was reflected in the operational discussions about them, led senior military commanders to prefer it to Option B, without even being aware of why.

Option A is crossing the Suez Canal; Option B is waiting for the Egyptians to launch an offensive and not crossing; Options A1 and A2 are, respectively, attacking Port Said and pressing Egyptian troops back to the western bank of the Suez Canal.

In conclusion, there is no way of knowing in retrospect whether any of the explanations offered here, which come from the field of the psychology of decision making, were part of what led to the war cabinet being presented with just one option and to the almost total disregard, without proper discussion, of the option of waiting for an Egyptian offensive. Having said that, an analysis of the discussions shows that it is entirely possible that the explanations presented here played some role in pointing them in a certain direction, even if that was entirely subconscious. We cannot learn any lessons about the past from any of this, but we can do so for the future, especially when it comes to engendering heightened awareness of the approaches that are at the center of the decision making process and to the cognitive biases that exist within them, which influence us all.

Sensitivity Analysis of the Decision Making Process

It is customary to examine the decision making process and the chosen path (the decision) according to their sensitivity to information and to the basic assumptions at the heart of the process. A sensitivity test examines to what extent a small change in the basic assumptions or information at the center of the decision can change the final decision. Or, in other words, how a small change in the independent variables (assumptions or information) can lead to a major change in the dependent variable (the decision). Why is this important? Not only for a retrospective analysis of processes and decisions, but also in real time. When decision makers lean toward a certain decision, which they recognize as highly sensitive to a certain basic assumption, it is expected of them to thoroughly examine the validity of that assumption. The more doubt that is cast on that assumption, and since the process is highly sensitive to it, it is feasible that a small change in the assumption could lead to a totally different outcome.

An analysis of the October 12 discussions indicates that the Chief of Staff formulated his recommendations according to several assumptions. The first was that the effort on the Syrian front had exhausted itself. The offensive was a success but had not brought about the collapse of the Syrian army. The second was that within two days at most the Air Force would no longer be able to provide support to the ground forces in an offensive. The third was that a war of attrition was being waged on the static front, that Israel could not remain in that situation for long, and that the Southern Command was capable of launching one large offensive and no more than that (Golan, 2013, p. 773). In addition, there was also the assumption that the diplomatic stopwatch was moving rapidly toward a ceasefire. Therefore, the Chief of Staff only presented one plan—the plan to cross the Suez Canal and capture territory on the western bank. However, the assumptions on which this sole recommendation was based were not necessarily solid. One small change could have led to fundamentally different decisions.

For example, the assumption that the Air Force would, within two days, no longer be able to support a ground offensive was not even brought up for discussion. The immediacy with which those present accepted statements by the Air Force Commander—namely, that once the Air Force dipped below a certain number of aircraft, it would no longer be able to support ground forces and that it was currently close to that level—is surprising, especially given the success of the Air Force in carrying out all its missions throughout the war with great success for two full weeks. While it is true that Israel had demanded additional aircraft from the United States because of the tough position the Air Force found itself in—and, in the end, it received those planes—in the test of reality, the Air Force continued to operate for many more days without getting additional planes. In the end, those additional aircraft only carried out a small fraction of the sorties during the war.[7] It is possible that had this assumption been examined more thoroughly, the Chief of Staff would have reached different conclusions, especially in terms of the urgency of the operation and perhaps his ability to bolster forces in the south, or to wait for an Egyptian offensive. This is not an attempt to delve into the realm of “what would have happened if…” Rather, we seek to highlight the importance of the thorough examination of sensitivity of the basic assumption at the heart of the recommendations, to which there is a high degree of sensitivity.

Another interesting sensitivity analysis concerns the sensitivity of the deliberations and the eventual decision (waiting for an Egyptian offensive) to the intelligence report that determined the fate of the discussion: To what extent was the decision making process sensitive to the arrival of the intelligence report and the precise timing during the cabinet meeting?

This question falls into two parts, first, sensitivity to the timing of the arrival of the intelligence report. If it had arrived before the start of the war cabinet meeting, it would probably have made that whole discussion superfluous, just as it brought about its abrupt halt the moment it arrived. If it had arrived after the meeting, but before IDF forces had started advancing toward the Suez Canal, the Chief of Staff could still have halted them and prepared for the Egyptian offensive. In other words, the decision to wait for an Egyptian offensive and then to cross the canal was not sensitive to the precise timing of the arrival of the alert within a range of one day either way.

Second is the obvious question of the sensitivity of the decisions to the very arrival of the intelligence report. To what extent were the discussions and the decision to wait for the Egyptians to launch an offensive sensitive to the intelligence about that attack? What would have happened had the Egyptians had executed their next move and attacked without Israel having prior intelligence?

In that case, as along as the attack happened before the IDF received the order to move toward the Suez Canal, presumably the Israeli forces would have contained it. Perhaps less successfully than they did when they were forewarned, thanks to the intelligence alert, but it was still this Egyptian move that the Chief of Staff and his top commanders had been waiting for the week since the war broke out. Bar-Lev himself said as much when he arrived at the General Staff headquarters on October 12 and stressed that his continued presence at the discussion was dependent on an Egyptian decision to suddenly move their armored divisions to the west of the Suez Canal “to complete what they refer to as Stage B—which is to reach the straits” (Golan, 2013, p. 764). In other words: the real sensitivity was not to the intelligence report but to the start of an Egyptian offensive before IDF troops began moving toward crossing the Suez Canal, a move that would have thwarted the Egyptian offensive or led to battles with the divisions crossing the canal at a time and place that were less planned for.

Thus, there is no question that the arrival of the intelligence report at the time that it arrived, in the middle of a war cabinet meeting, was almost perfect in terms of the decision making process and is well suited to many war-time narratives. “It was as if it were taken from the storyline of play written by an expert playwright” (Bartov, 1978, p. 192). Yet despite the huge importance that the literature has attached to the intelligence report, in our analysis the decision making process had no real sensitivity to it.

Conclusion

On Friday, October 12, 1973, the leaders of Israel’s security establishment gathered for a series of crucial decision making meetings to discuss how Israel would deal with the Egyptian army on the southern front. The subjects discussed converged on this one day after the failed counteroffensive on the southern front on October 8 and the stabilization of that front between October 9 and 11 and, at the same time, the success of the counteroffensive inside Syrian territory the previous day, which despite being a welcome accomplishment, failed to lead to the collapse of the Syrian army.

These fascinating discussions, whose minutes have been declassified over the years, highlight the extent of the dilemma Israeli decision makers were facing, at a time when the military and political timetables were tight and, as they saw it, they did not have a viable alternative at that time to defeat the Egyptians and restore Israeli deterrence.

Using primary and secondary sources, this article attempts to analyze in retrospect those discussions, but from the perspective of what was known on that day, in order to shed light on the three main elements in the strategic decision making process. It therefore suggests viewing that day as a singular event in the history of the State of Israel, in which the three pillars of Israel’s defense doctrine—decisive victory, early warning, and deterrence—faced extreme difficulties. The challenge to the doctrine on that day stemmed from the IDF’s inability, according to the Chief of Staff and his top generals, to achieve a decisive victory over the Egyptian army. In our opinion, this had ramifications on various aspects of the IDF’s force buildup after the war, especially the extraordinary investment in technological force buildup and the establishment of technological military superiority, an advantage that is less sensitive to the quantitative asymmetry between Israel and the other countries in this region.

The second issue tackled in this article is the decision making process itself in the context of the alternatives that were proposed and examined during the marathon consultations on that day. The alternative of waiting for an Egyptian offensive, repelling that offensive, and subsequently crossing the Suez Canal in order to secure a decisive victory—the option that in the end was employed—was not given, to our understanding, enough room for in-depth discussion. This is despite the fact that there were some present who did not think that the option of crossing the canal was a good one (the deputy Chief of Staff); despite the fact that this very day marked the number of days in Egypt’s plan until it launched the next stage of its campaign; despite the fact that the possible ramifications of the operation in Syria on Egypt were not considered; and especially despite the fact that the political echelon, headed by the Defense Minister, asked the Chief of Staff to indicate which military option was the best, without taking the political consideration of a ceasefire into account.

We suggested, based on studies from the field of the psychology of decision making, that perhaps some of the reasons that this option was overlooked were not related to the information available to the decision makers—i.e., to the content of the options themselves—but to various aspects of their characteristics, to the way they were presented, and to the other alternatives that were on the table. This leads to an option not being selected due to various psychological parallaxes and in this case: anchoring the decision to think in terms of days instead of weeks; adhering to the status quo concept of the IDF as a proactive army that secures decisive victories; possible regret in the case of failure; and alternatives compared on opposing axes. All of this happens without the decision makers being at all aware of these parallaxes and their influence on them.

Finally, since one of the most important variables when it comes to examining the decision making process is an analysis of its sensitivity to various basic assumptions and to the information that forms the basis of the decision making process, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on the Chief of Staff’s basic assumptions, those that led him to recommend his preferred course of action. We showed that it is feasible that a sensitivity analysis of these assumptions—especially the assumption that the Air Force was reaching the point when it would no longer be able to provide support for the ground forces—could have led to a reevaluation of the options being discussed, the timing, and the rush to make a decision.

Moreover, we analyzed the sensitivity of the decision making process to critical information that arrived in the middle of consultations—the intelligence report about a planned Egyptian offensive to expand its bridgeheads. We suggested that despite the prevalent view on the importance of that report to the strategic decision making process, it may have brought about the immediate end of the war cabinet meetings, but the IDF’s preparations for such an eventuality were not particularly sensitive to the timing of its delivery. Moreover, as long as the Egyptians launched their offensive before the IDF tried to cross the Suez Canal, the very fact that the report arrived at all, and not just the timing of its arrival, was not at all critical to what happened on the ground.