Strategic Assessment

This paper proposes a new approach to the use of the term “governance” in the context of the Negev. The research traces the evolution of international academic discussion about the term, which has broadened in scope beyond the limits of the governing establishment, in contrast to the Israeli discourse that has until now adopted a more limited approach. In accordance with the broader use, this research shows that in the Negev, in parallel to the institutionalized establishment, there is an additional independent system of governance, dictated by historical tribal rules. This governance controls many aspects of the lives of the Negev Bedouins. The paper focuses on four issues, population registration and documentation, control of the land, polygamy, and conflict resolution, and through them illustrates the interface between the two governances. It shows that the Israeli establishment, by its conduct over the years and its failure to identify and acknowledge the power of tribal governance, has helped to strengthen it at the expense of state governance. In conclusion, the paper also offers policy recommendations.

Keywords: Bedouins, governance, Negev, polygamy, sulh, land dispute

Introduction

A 2021 report from the State Comptroller entitled “Aspects of Governance in the Negev” points to a variety of areas where the State of Israel fails to apply its laws in the Negev (State Comptroller, 2021). This report follows previous State Comptroller reports on failures of the establishment with respect to Negev Bedouin affairs (State Comptroller, 1967, 2011, 2016).

The subject of governance has been addressed by researchers in a range of disciplines, and is linked to theories from the field of public policy—an area of research that developed in the second half of the 20th century. Its multidisciplinary character and importance increase “as the features of the democratic state become more complex” (Nachmias & Meydani, 2019, p. 13). Although government authorities are at the center of public policy delineation and bear responsibility for its implementation, over the years there has been growing recognition of the importance of understanding the activity and impact of other elements, such as interest groups, capital enterprises, and economic and other international bodies (Nachmias & Meydani, 2019).

The study below deviates from the Israeli focus anchoring the term “governance” in state establishment activity and proposes a new approach to the use of the term in the context of the Negev. At the heart of this approach is the argument that in parallel to establishment governance in the Negev, there exists another independent and separate system, based on Bedouin tribes. The use of this term to describe both systems places them side by side, creating a horizontal parallel between them. This differs from the questions asked until now about governance, which focused on the establishment and its vertical aspect, namely, the role of state governing authorities and non-application of the law to the population. Ignoring the power and the impact of Bedouin tribalism and failing to recognize it as a competing governance system leads the Israeli establishment to encourage and reinforce it, to a large degree at the expense of state governance. Therefore, this paper does not discuss the broader context of state control of minorities,[1] nor the difficulties of the Israeli establishment to formulate and implement such policy in connection with the Bedouin population of the Negev—topics that have been the focus of many studies (Yahel & Galilee, 2023).

This paper opens with a definition of the term governance, its conceptualization, and its link to national strength. It is followed by a presentation of Bedouin tribalism as a competing system of governance, and then analyzes the interface between the governances through a discussion of four issues: the system of population registration and documentation; control and use of the land; polygamy; and the use of force in conflict resolution. The paper ends with principal conclusions and policy recommendations.

What is Governance?

Evolution of the Term Internationally

The term governance is linked to the words govern and government, which come from the Greek word kybernan (κυβερναν), itself originally applied to the activity of steering a boat. The word eventually led to the Latin word gubernare, and then govern in the sense of guiding the public,[2] and hence government and governance (Levi-Faur, 2012, p. 5).

There are two English words to translate the Hebrew word meshilut. One is governance, describing institutions and focusing on government, control, rule, and administration; and the other is governability, which focuses on processes and the ability to govern or to implement governing policy (Coppedge, 2001).

A review of international academic literature shows that the terms governance and governability were traditionally used only in the context of state governing bodies (Kaplan, 2010). Since the 1980s, however, the term governance has expanded to cover non-state bodies. The economist Oliver Williamson (1979) referred to “market power” as governance. After him, sociologist Woody Powell (1990) and political scientist Rod Rhodes (1990) developed the use of the term in the context of informal authority, and laid the foundation for understanding that authority in governance can originate from various sources, which may compete with, haggle with, adapt to, or ignore each other.

Since then, the definitions and discussions of the term have multiplied, and not only to include non-state elements.[3] It is also used to highlight changes in the understanding of the nature of government—from a centralized state framework to a diverse framework including the involvement of market elements and other actors from civil society (Kooiman et al., 2008; Rhodes, 1996; Stoker, 1998). According to legal experts Franz and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann:

The past twenty years have witnessed important changes in the ways in which government is exercised. A plurality of non-state actors has become involved in what until recently was considered the sole domain of state agencies. At the same time, the academic and political perception of these changes has changed as well. To capture these processes, the term “governance” was coined, and it has generated a substantial body of literature. (Von Benda-Beckmann & Von Benda-Beckmann, 2009, Ch. 1, p. 1)

The work of sociologist Asa Maron also showed how scholars from various disciplines gradually began to see governance as “a research perspective for the study of changes in the state and policies of later modernism, [where] the central assumption is that policy is shaped within a heterogenous organizational field with numerous actors” (Maron, 2014, p. 169).

Political scientist Claus Offe took another step in this direction and argued that the new academic use of the term governance comes in contrast to central government (Offe, 2009). The term is intended to stress the state’s inability to provide a solution to strong and urgent public problems, and the fact that non-state external actors actually have the power to take autonomous action, to the extent of thwarting classical establishment action. Linking the emptying of state authority and the decline in its ability to control with the discourse on governance is also found in the work of sociologist Rami Kaplan (2010).

In the opening of his book on governance, political scientist Mark Bevir explains:

Governance refers, therefore, to all processes of governing, whether undertaken by a government, market, or network, whether over a family, tribe, formal or informal organization, or territory, and whether through laws, norms, power, or language. Governance differs from government in that it focuses less on the state and its institutions and more on social practices and activities. (Bevir, 2013, p. 1)

Although most of the studies presented above deal with changes in the term governance, there has been a similar broadening with respect to the term governability. Today, the international academic discourse on both these terms is linked not only to classical state institutions, but also to non-state elements, processes, and forces, some of which are opposed to the establishment.

Development of the Concept in Israel

The Hebrew word meshilut is a neologism. It did not appear in the popular Even-Shoshan dictionary, its first entry in the Hebrew Wikipedia was only in March 2023, and its first uses are found in the 21st century. One of the earliest occurrences in Hebrew is found in Yehezkel Dror’s Letter to a Jewish-Zionist Israeli Leader, which uses the word in the context of a model to improve the performance of Israeli Zionist leaders (Dror, 2005). An examination of the definitions of the Hebrew word does not sufficiently clarify its links to the English words governability and governance. On the one hand, the Academy of the Hebrew Language defines meshilut with content relating to both English terms: “the actions of a governor” and “the ability to control and supervise government institutions.”[4] On the other hand, the definition in the online Avnion Dictionary covers only the sense of governability, “the ability of a regime to achieve its desired results.”[5]

The definition in the Avnion Dictionary conforms to the general usage of the term in Israel (Gohar, 2021), mainly linked to the demand to strengthen the ability of the government to control other branches and elements of government and institutions, such as the judiciary and civil service employees, who are part of the executive branch. As clarified by Gayil Talshir, meshilut is linked to a situation where “the government lacks the power and authority to lead policy, and therefore…state mechanisms must be weakened while simultaneously establishing a small but strong government” (Talshir, 2020, p. 18).

In this vein, the 34th Israeli government defined its basic policy outline in May 2015: “The government will work to change the system of governing in order to increase governability and government stability, and will promote reforms in the field of governance to improve stability and governability.”[6] The article “The Path to Democracy and Governance” by former Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked likens governance to the action of a strong railway engine pulling the government cars to their destination (Shaked, 2016). In this approach, governance is the ability of the elected politicians to define their objectives, formulate their policies, and implement them (Harel-Fisher, 2020, p. 110).

A different emphasis in the definition of governance can be found in a position paper on governance and its implications written by Lior Shochat (2007) in the National Security College. Shochat chooses an approach combining institutions and processes, while limiting governance to state government, by referring to the source of its authority—the democratic regime:

Governance is a regime’s ability to use legitimate authority in order to implement democratically acquired policy, while providing systemic leadership and direction, creating structural and procedural conditions, strengthening the ability to act, solving problems, and recruiting the resources needed to achieve society’s collective objectives. (Shochat, 2007, p. 13)

The State Comptroller’s report of 2021 adopts the same approach.

In the collection of articles The Vision of Israeli Governance, dealing with various governance lapses unique to Israel, Assaf Meydani proposes using meshila to designate thinking on the subject of governability, thus distinguishing it from the word meshilut (Meydani, 2015, p. 11). In the introduction to the collection, Meydani presents Bevir’s broader definition (quoted above), but the book as a whole focuses on the activity of institutional bodies in Israel.

Thus, the term meshilut in Israel, while not distinguishing between institutional governance and procedural governability, is used mainly to describe the function and relations between state institutions, with the emphasis on the government, and a focus on the question of implementing state laws and policies adopted by the state authorities. This usage lacks the broader use of the term found in international discourse, to describe other non-state forces and elements and to understand the relations between them and the state establishment.[7]

It is not essential for this paper to separate the procedural and institutional meanings. It follows the broader international discourse and uses governance to describe a non-state non-establishment Bedouin tribal system.

Governance and National Power

What is meant by national power has engaged numerous experts, who define its limits in different ways. The current trend is to look at the subject in its broader sense, reflecting an array of fields: military-security, political, economic, and social. National power is measured by how far individuals identify with the goals of the state (Ben Ari, 2002), and by the degree of authority that the state has over individuals, its ability to persuade, and its legitimacy to exercise its power over others (Yaron, 2002). In other words, national power is the ability to promote and realize goals by influencing the conduct of individuals. In this sense it is clear that if there is an alternate governance system, with a substantive hold on a wide range of social, political, geographical, personal, and economic aspects of a specific population sector, in a way that significantly overrides or changes the rules of central government, this system is a threat to state governance and undermines its power (Shochat, 2007). Therefore, the power of tribal governance has implications for the national power of all Israeli citizens, and the preservation and encouragement of this system affects national power.

Tribal Governance among Bedouins in the Negev

The system of Bedouin tribal rules, tribalism, has been formed over many years as a response to the enormous challenges faced by nomadic groups in severe desert conditions, in areas where there was no external government presence. The rules of conduct that arose within and between the Bedouin tribes were designed to secure the survival of the group, and they consist of a collection of dos and don’ts, passed down orally over the centuries from father to son. These rules are generally shared by all Bedouin tribes in the Middle East (Stewart, 2006). Muhammad Suwaed estimated that Bedouin tribalism is relevant for about 25 million people, and regulates behavior in large areas of the Middle East and North Africa (Suwaed, 2015).

Traditionally, the main social framework for making decisions is the tribal unit, which is a kind of dynasty based on the strongest ties of all—blood ties. Members of a tribe see themselves as descendants of a common ancient ancestor on their father’s side. The traditional tribal leadership consists of respected men from the largest and most influential families in the tribe, led by a sheikh who is the link between the tribe and the outside world. This leadership is not the product of a democratic, free selection process, in which every man and woman has an equal voice, but mainly the result of size and strength. Alongside the tribal leadership is a judicial system, composed of respected tribesmen with knowledge of tribal law, who are appointed with the parties’ consent to decide specific conflicts. The preservation of order and stability in society is based on strict and uncompromising enforcement of these rules, with severe collective punishments for infringement.

A central principle dictating social conduct relates to honor. According to the anthropologist Frank Stewart (Stewart, 2006), honor in the Bedouin context is of a binary nature—you either have or don’t have honor. Female modesty and control of the land are two of the main areas where any deviation has implications for honor. The loss of honor is a serious social stain with severe consequences, and because of its centrality and importance, there are tribal rules on action to be taken in order to maintain honor or restore lost honor, including restricting freedoms, using force, and even taking a life.

Another basic principle is the collective responsibility within the tribe, expressed mainly by the “blood money group,” sometimes referred to as hamula or hams in Arabic. These are members of an extended family on the man’s side, who bear mutual responsibility and uncompromising loyalty to each other. This means an instant and unreserved response to a request for help from a member of the hams, irrespective of the merit of his actions. Tribal collectivism is different in many ways from kibbutz collectivism. The kibbutz is a collection of free individuals, each with his/her own opinions and rights, who have chosen to organize as a group and from time to time define rules for the group. It is generally possible to join the group, leave it, or move to another such group at will. By contrast, tribal links are dictated by birth through the father’s tribe, and individual identity is derived from the group identity. The rules of conduct are uniform and predefined (Stewart, 2006).

The concept of human rights—which places the individual as an independent entity with rights and duties, and other liberal values of freedom and equality on which Western state governance is built—is foreign to tribal principles. For example, the tribal system does not recognize the right to freedom of expression, including the right of the individual to publicly criticize the group to which he belongs. A critical statement could damage the unity of the group and weaken it against other groups. Women are not equal to men. Girls belong to their fathers, and after marriage, to their husbands, and they must obey instructions from their husband’s family. In addition, tribalism developed orally in a society without writing, and therefore gives no weight to written documentation and laws.

Following the establishment of the State of Israel, the state leadership hoped that with the transition from nomadic living to permanent settlement, tribalism would decline and perhaps even disappear (Yahel, 2018; Katushevsky et al., 2023). The expectations were that once the Bedouin population is exposed to the benefits of democracy in a welfare state with a liberal and modern lifestyle, it would eliminate differences between women and men and between family origins. And indeed, there have been some far-reaching changes in Bedouin society—formal education and healthcare are two prominent examples.

However, the power of tribalism as a sociopolitical system has remained, and it continues to dictate the conduct of the Bedouins in the Middle East (Rabi, 2016), including many of the approximately 300,000 Bedouins living in the Negev. Daily life is affected by the tribal rules of what is forbidden and permitted, honor, and tribal law, in which the rules of collective responsibility are applied to resolutions of disputes. Women are severely restricted, particularly in the public space. There are also frequent violent clashes over the control of land. The uncompromising obligation to support members of the blood money group increases the number of people involved in disputes. For protection and to deter hostile groups, they acquire arms and seek to impress their strength and courage—graded by their objectives and various weapons—on those around them. Social media are also used to spread photos and videos of showcase demonstrations of power, as well as direct and indirect threats.[8] If someone is injured or killed, his blood money group has the right to vengeance, namely, to kill a member of the attacking group, unless a sulh is arranged (see below). Katushevsky et al (2023) attribute the persistence of tribalism to its function as a social network of mutual commitment and help, and a mean of obtaining control of economic resources in an environment of shortages and competition. Consequently, the system of Bedouin tribalism, as a separate system of governance in the Negev, is not only relevant but even dominant.

Even though the Bedouins are Muslims, tribal traditions often take precedence over Islamic commands (Yahel & Abu Ajaj, 2021). According to a member of the Islamic Movement and Mayor of Rahat Faiz Sahiban: “Tradition is stronger than good intentions. Tradition is even stronger than religion for us” (Mosco, 2021).

What follows is a discussion of encounters between state governance and tribal governance, focusing on four different issues.

Documentation and ID Card Registration

State governance is applied to people living in a defined geographical area, whose place of residence usually determines their legal status. Therefore, one of the main mechanisms used by the state is a database of its population. Democratic involvement, such as the right to vote in elections, derives from the place of residence. Location is also relevant for a variety of rights and obligations and is used for formal communication and official notices from the state. It is therefore obligatory to register one’s address in the most important identity document issued to Israeli citizens—the ID card. The Israeli ID card is issued by virtue of the Population Registry Law, 5724-1964, and the obligation to register the holder’s address is stated in Section 2(11) of the law. The law also stipulates that the address is public information that can be used by the authorities and all citizens.[9]

Unlike the state’s institutional mechanisms, the Bedouin mechanisms for management and traditions, which derived from a nomadic tribal society, never included written documentation. If any proof was required, it was given under oral oath. Since the geographical locations of the nomadic tribes changed, the fixed component of identity was tribal affiliation. According to Aref al-Aref, “Nothing is more hateful to a Bedouin than asking him his name…and also if you ask him, for example, where he or his tribe lives, from whence he came and where he is going. On such matters the Bedouins maintain a level of secrecy that is almost hard to believe” (al-Aref, 2000, pp. 6-7).

In the early years of the state, the Bedouin population of the Negev continued to live in tents and relocated from time to time. Until 1966 they were subject to military regime in the framework of 18 tribal units (Ben-David, 2004). Unlike the general population, the address field in the Bedouin ID card contained the name of the tribe. Sometimes the same “address”—tribal name—applied to people separated by many kilometers. Contact with state authorities, including correspondence, was handled centrally through the sheikhs (Mintzker, 2015).

In a gradual process that gained momentum in the late 1960s, the Bedouins exchanged their tents for shacks, and then for permanent buildings, mostly built without authorization. At the same time, the state began establishing Bedouin towns in the Negev, where Bedouins were given free plots of land (Yahel, 2019). Those who moved to the towns, about 220,000 people, changed the address field in their ID cards, but the cards of an estimated 80,000 people still bear only the tribe’s name. Many have not changed their location for many years, and some have even moved to other places in the Negev and beyond, but for various reasons prefer not to change their ID card details.

The absence of an address has many implications. It makes it hard for the authorities to locate residents and enforce obligations, since most of the demands of the state system vis-à-vis the population, including imposition of penalties, fines, reports, and fulfillment of formal legal requirements are based on a registered address. At the same time it also makes it hard for citizens to exercise all their rights. One outcome of the absence of address was discussed in the Knesset in 2020 at the initiative of MK Said al-Harumi (since deceased) of the United Arab List (Ra’am), himself a Bedouin from the Negev. Al-Harumi pointed out that income tax benefits were only given to residents of state-established towns defined and mentioned in the legislation. In 2020 he raised a proposal that would give benefits also to those whose address was a tribe name. The Knesset was asked to add the words “significant Bedouin tribes” to the list of places eligible for tax benefits.[10] The proposed amendment was tabled for discussion in the Knesset committee and has not been raised since.[11] This amendment, if passed, would anchor tribal affiliation even more deeply in legislation. In media coverage on the proposed bill, nobody expressed surprise over registration of the tribe name, and nobody suggested changing the address in the ID card from the tribe name to a physical location to enable definite identification.

Control over Land

Unlike the previous case in which tribal affiliation interferes with state governance operations, control over an area of land, the ability to decide who has the right to enter it, what can be erected on it, and what rules apply to people in that area are at the center of head-on clashes between the two governances, in which each side claims the upper hand. State governance is based on the provisions of Israeli laws regarding land rights, while Bedouin governance derives its power from tradition and the sword. Note that for the sake of the present discussion we are not considering the question of who is right or whether the solutions proposed by the state are proper or not; other studies deal with these issues.[12]

Israeli law, based on the Ottoman Land Law of 1858 and followed by the Land Law, 5729-1969, defines the system of rights to land, including who is recognized as the owner of the land and how it can be used.[13] These laws demand reporting and registration, and are intended, inter alia, to prevent individuals from taking control of land without government approval. For this purpose, the British Mandate introduced the Land Order (mewat) in 1921. Another initiative by the Mandate was intended to replace the Ottoman deficit records, using a mechanism developed based on mapping and measurement of land plots and systematic recording of the rights to these plots.[14] Ultimately, all the land in the state was registered, except for about 600,000 dunams, almost all in the Negev. A minority of the Bedouins claim private ownership over this land and have lodged claims against the state. However, since they lack the proof required by law to establish their ownership, they have no interest in promoting court rulings on the claims, particularly as they have de facto control of the land. Apart from a few exceptional cases, the state has also refrained from referring the claims to the courts, due to reluctance to clash with those claiming ownership. In the few proceedings tried in court, the state won. Over the years there were those who called on the government to implement the law and the court rulings and to regulate the ownership of land in the Negev, and there were others who demanded a change to the law and recognition of the Bedouin as owners of the land without demanding proof as determined in the court rulings (Yahel, 2019; Kedar et al., 2018).[15]

In 2003 the government decided to settle the matter by establishing a unit in the Southern District Attorney’s office, which was given the task of submitting the ownership claims to the courts. Comprehensive organizational preparations took place, including mapping the unregistered land. Some years after the start of the project, when a few hundred claims had been filed with the courts, the government decided to appoint a commission to recommend suitable policy for regulating Bedouin settlement in the Negev.[16] Former Supreme Court Justice Eliezer Goldberg was appointed head of the commission, and two of its members were Bedouins from the Negev with land claims. The commission’s recommendations were submitted in 2009 and included statements on a historic connection between the Bedouins and the Negev, the importance of equality in rights and obligations, and the need for a quick legislated resolution. On the land issue, it recommended a mechanism for compromise, including graded compensation, where the percentage of compensation declines according to the size of the claim. It also recommended authorizing existing clusters of buildings as far as possible, and establishing a system of enforcement that would ensure the demolition of any subsequent buildings (Goldberg Commission Report, 2008). Pursuant to the report, the government decided to appoint an implementation team led by Udi Prawer from the Prime Minister’s Office. The work of the implementation team and the legal proceedings continued concurrently. After two and a half years, the team submitted its conclusions, which significantly increased the size of the compensation compared to the Goldberg Report. Publication of the team’s conclusions aroused wide public protest, including the fact that about 30,000 Bedouins would be required to move from their current illegal dwellings to legal localities. The protests led to a decision to appoint Minister Binyamin Ze’ev Begin to conduct a public hearing. In addition, a guideline was issued to stop the legal proceedings in all but a few cases, such as when the land claimants wanted to continue the proceedings (al-Uqbi v. State of Israel, 2015; Yahel, 2019). The termination of the legal proceedings was ordered by the Justice Ministry headquarters in coordination with Prawer. Although many elements objected, the move was justified on the grounds that the proceedings caused unrest among the Bedouins, making it harder to reach historic understandings with them.

Once again, public protest arose when Begin submitted the conclusions of the hearing, which were accompanied by a proposed bill with significantly higher compensation than the amounts suggested previously. In the years since the proceedings were stopped, no new law has been passed and no understandings have been reached—quite the opposite. Those claiming land have strengthened their hold, with more illegal construction on the disputed land. They want the state to authorize the illegal construction and set up towns for them, and indeed, in recent years there has been an extensive process of legalizing existing buildings (Dekel, 2023). The Bedouins base their demands on the claim that they were deprived and suffered discrimination in the state’s planning framework, as they were never permitted to obtain building permits for the places where they lived, including cases where the family had lived in the same place before the establishment of the state. They also complained that the localities built for them did not meet their needs or wishes.

The strict legal mechanisms for dealing with the incursion onto state land and the illegal building in the Negev and elsewhere,[17] like the authority intended to enforce land laws and work with the police and other law enforcement agencies to contain the problem,[18] do not provide a response to the situation in the Negev.

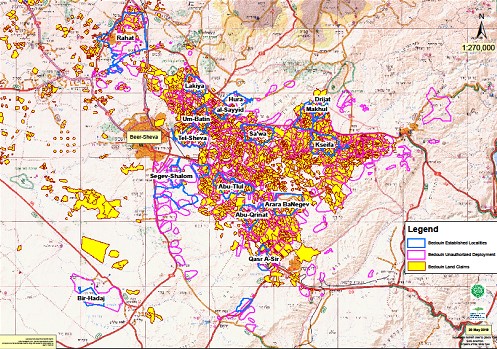

Map 1 shows the situation of undecided land claims, state-built Bedouin towns, and the extensive illegal construction in the area.

Map 1: Bedouin Deployment in the Negev

While the government avoided systematic implementation of the land laws in the Negev, the tribal rules for land control prevailed. According to these rules, control of land is achieved by the power of the sword, and not by written deeds. Aref al-Aref, a historian and Arab nationalist who was the district officer of Beer Sheva during the British Mandate (1929-1938), clarified how tribes gained control of land:

At the start of the period when the Bedouins were first inclined to acquire land, they would just grab land for themselves. No government claimed ownership of this land, and nobody sought to buy it from its owner, so anyone strong and violent could seize land for himself…How did they seize it? A Bedouin goes to a piece of land that he likes, shows the land to everyone around, and says, “This is my land.” (al-Aref, 2000, p. 164)

According to tribal rules, the person who seizes the land is deemed its owner with full rights to it, including the ability to decide what can be done with it, what will be built, and who can stay there. He can also collect payment for use of the land, including passage across it. Trespassing or unauthorized entry on someone’s land is an affront to his honor and can be opposed with physical force. In most cases the threat is sufficient to deter others from entering the land without permission, although recently there have been a growing number of violent clashes between clans around land disputes, sometimes leading to deaths. Within the state-established towns, many of the violent struggles are linked to control of the new plots available for allocation. There are gunfire incidents almost nightly, as demonstrations of strength and warnings, particularly in Tel Sheva and in Rahat, although in other places as well (Ifergan, 2021; Curiel, 2021). Tribal control of land includes the demand to determine the identity of anyone who enters and supplies services, for example, the identity of the school principal. In many cases, people who come to carry out infrastructure work on the land are required to pay protection money, sometimes disguised as an offer they can’t refuse, for guard services. Indeed, both private and public bodies prefer to pay those who control the land so that they can carry out their work. This was the case when Road 31 was built and when the Electric Corporation laid high voltage lines. In some cases, the required infrastructure work was not done, and sometimes infrastructure locations were changed at enormous cost due to the demands of the land controllers. Examples can be found in the town of Lakiya, where a section of the main road was not paved for many years due to fear of the ownership claimant, and in another case, objections to the deep burial of sewage lines in Drijat resulted in significant extension of the lines at a cost of millions.

In Rahat, an announcement by the local leadership of its intention to retain land in the city’s extension for its descendants was enough to make members of the Abu Qweider clan renege on the understandings they had signed with the state about moving to live in the extension. The Supreme Court proceedings, which ultimately declared that the people of Rahat had no right to decide who would enter the extension land, proved meaningless on the ground.

Control by tribal rules is also reflected in the tens of thousands of structures erected with no building permits. Over the years, the state has failed to fully enforce planning and building laws among the Bedouins in the Negev.[19] Even in state-established Bedouin localities there is a great deal of illegal construction, including building in parks and other public spaces, as well as “private roads” laid irrespective of any town plan (State Comptroller Report, 2021). Moreover, the scattered groups of illegal buildings on hills and valleys in the Negev could potentially expand almost without limit. The residents of the buildings do not pay for the land or for a building permit. Education and welfare services are provided with no requirement to pay local taxes (arnona). Over the years the state has retroactively authorized many illegal buildings (Yahel, 2019), thus reinforcing the tribal rules that whoever grabs the land is the owner.

Women’s and Children’s Rights in the Family: The Issue of Polygamy

Another dimension of the clash between the two modes of governance relates to a fundamental concept of tribalism that permits multiple wives, versus a fundamental concept in many countries, including Israel, that forbids multiple marriages with an eye to the protection of human rights.[20] According to international law, polygamy[21] is deemed not only a form of discrimination against women and a violation of their right to equality, but also a situation that is harmful to children.[22]

Based on a cautious estimate of the Central Bureau of Statistics published in 2017, about 18.5 percent of Bedouin men with children are in polygamous marriages (Summary Report, 2018). Previous studies indicated a higher proportion—30 percent on average (Research and Information, 2014; Abu Rabia et al., 2008; Lapidot-Firilla & Elhadad, 2006). According to other data, in the years 2016-2019, 700 men entered polygamous marriages (Research and Information, 2022). In the past, polygamy was the preserve of a minority with means, but over the years it has become more prevalent, either due to the generally improved economic situation or the ability to bring wives from the Gaza Strip and the West Bank at a lower price per bride (Adler, 1995). The phenomenon is not only common among the older population but also among the educated younger generation (al-Krenawi, 1999; Ben-David, 2004). Although in most cases polygamous marriages involve a second or third wife, in the past there were cases such as Sheikh Saliman al-Hozail, who married 39 women and left over 70 descendants, and more recently, Shahada Abu Arar, who married seven wives and has 63 children.[23]

Polygamy among the Bedouins is linked to tribal norms preserved from the past, whereby a tribe’s strength lay in the number of fighting men it could muster. Numerous wives acquired from other groups means numerous children and thus increases the dynasty’s numerical capital and strength (Yahel & Abu Ajaj, 2021). Research studies provide other reasons for the survival of polygamy today, linking the phenomenon with the tightly knit patriarchal social structure of Bedouin society. The explanations point to polygamy as a status symbol, evidence of the man’s power and wealth, the family’s work force and increased political power (the more family members, the greater the chances of some of them achieving powerful positions), permission by Islam, custom whereby the choice of the first wife by the parents reflects a commitment to the extended family, while the second wife is freely chosen by the man, a solution for women who have difficulty finding a husband, accessibility of Palestinian women from the territories, the fear of divorce, and a mode of conflict resolution between families or tribes (al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo, 2005; Research and Information, 2014; Summary Report, 2018). Tribalism does not limit the number of wives a man can marry, unlike Islam, which limits the number of wives to four, with strict requirements for permission to marry additional women.

Israeli law, like international law, opposes polygamy. Section 176 of the Penal Code 5737-1977 states that “A married man who marries another woman, and a married woman who marries another man—can be sentenced to five years in prison.”[24] The prohibition is supported by several studies of Bedouins in the Negev, linking polygamy to oppression of women, harm to children, increased economic distress, weakness, and violence (al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo, 2005, al-Krenawi et al., 1997). Polygamy hinders the process of strengthening the status of Bedouin women and harms their dignity. It preserves the patriarchal family structure and perpetuates the traditional attitude toward women (Adler, 1995, p. 134).

Polygamy is linked to other criminal behaviors, including domestic violence, trafficking in women, trade in women (buying women and importing them from the Palestinian Authority territory to Israel, where they are defined as illegally present and their children are not fully registered in the Population Registry), National Insurance fraud, poverty, distress, dropout from school, juvenile delinquency, and involvement in nationalist crime (Summary Report, 2018; Research and Information, 2022). This is in addition to the other difficulties it causes in the fields of housing and planning (Ben Baruch et al., 2018).

In the past, there were attempts to bypass the legal prohibition in various technical ways, but the law stipulates that the existence or absence of marriage is determined according to the laws of personal status. In the case of the Bedouins, the test is whether sharia, Islamic legal law, defines the relations as “marriage” or not (Adler, 1995). Over the years, sharia courts have permitted such marriages retroactively, and the state has taken no action against the sharia courts (Aburabia, 2022; Greenzeig, 2022).

In spite of the wide prevalence of the phenomenon, which according to Judge Alon Gabizon amounts to a “national disaster,”[25] Israeli governments have chosen not to confront it. On her appointment as Minister for Justice, Ayelet Shaked established a team representing various ministries, local authorities, and civil society to examine ways of dealing with the negative effects of polygamy. In the summary report submitted in 2018, the team stated that polygamy was an expression of “the absence of (state) governance” (Summary Report, 2018, p. 15). A survey by the Knesset Research and Information Center in January 2022 found no evidence of a reduction in the incidence of polygamy (Research and Information, 2022).[26]

Moreover, in tandem with avoiding enforcement of the legal ban on polygamy over many years, the state has provided and still provides economic and other incentives that encourage it. One of the less familiar incentives is the state-funded allocation of land for residential buildings to polygamous families. In order to encourage the move to state-established localities, the state provides Bedouins living outside those places with about half a dunam of land for residential purposes. The plots are allocated according to the number of wives, so that men with more than one wife receive more land (Yahel, 2017). This derives from a 1979 decision, when Israel had to evacuate Bedouin families living around Tel Malhata in the Negev quickly. The land was needed to build the Nevatim Air Force base, to replace the base evacuated in Sinai as part of the peace treaty with Egypt. To help the population relocate, the state established two new towns, and decided that each evacuated family was entitled to a free dunam of land.[27] The State Attorney was asked to draft an opinion regarding the number of plots to be allocated to families with more than one wife, and stated that more than one plot of land could be given, on condition that before the evacuation, the wives had lived no less than 50 meters from each other.

In this decision the State Attorney did not refer to the question of legality. Ignoring the provisions of the law prohibiting polygamy sent a message that not only was polygamy permitted, but that it could even be a source of significant economic benefit, such as free land. The land allocations were accompanied by grants for moving and other expenses. Ten years later, in 1992, when the government decided to apply the benefits granted by virtue of the peace treaty to all Bedouins in the Negev, the condition of minimum distance between the houses of the wives was abandoned. Since then, any Bedouin interested in moving to a state-established locality has received free land according to the number of his wives, with no review of the distance between their former residences. According to figures from the Israel Land Authority, in the years 2013-2016 about 100 plots of land were granted without a tender to wives living in polygamous families (Summary Report, 2018, p. 108). This number has increased to several hundred in view of the significant rise in land allocations in the last five years. The authors of the Summary Report chose not to order an end to allocations of extra plots to polygamists.[28]

Evidently, on matters of protecting the rights of women and children in the family, the state fails to enforce its laws, tribal principles rule, and there are incentives granted that in effect encourage polygamy.

Conflict Resolution: The Sulh

Another interface between the state and tribalism is linked to the use of force to settle blood feuds. The debate focuses on the mechanism of the sulh.

The roots of the sulh go back centuries, emerging before the rise of the Islamic legal system (Shahar, 2018; Justin, 2020; Khadduri, 2012; Lyon, 2018; Othman, 2007). The mechanism is designed to resolve conflicts in the absence of an established judicial authority and relies on communal consent (Justin, 2020). The underlying idea is to resolve conflicts through cooperation and mediation, and the aim is to preserve order and community stability (al-Humaidhi, 2015). Wherever institutional legal mechanisms were weak or distant, the sulh was a tool used to restore stability, prevent bloodshed, and restore communal peace, security, and harmony (Yanai & Adwi, 2016). The use of the sulh is accepted in Bedouin society throughout the Middle East, and in some countries, it has been enshrined in law (Dupret, 2006). Its main implementation concerns incidents of murder, honor, and property (Abu-Rabia, 2018). The process is managed by respected members of the local community who have no institutional position, but who have authority in the social, family, or tribal structure (al-Jabassini & Ezzi, 2021).

The sulh is based on the concept of group responsibility, which differs materially from the concept underlying the Western and Israeli liberal legal system (Mugrabi, 2019). Bedouin tribal society is essentially collectivist, and clearly prioritizes the interests of the group over those of the individual. In the classic sense individuals have no independent status as the owners of rights and obligations, but only as part of the group. Therefore, if one individual harms another, collective responsibility applies. His actions are the responsibility of his entire blood money group and give the members of the victim’s blood money group the right to a reciprocal response—revenge. Revenge is not necessarily taken on the individual who caused the harm but can be exacted from any member of his blood money group and is considered a legitimate means for restoring the balance of power to what it was prior to the harmful act.

The sulh is designed to preempt the act of revenge by replacing it with other options, such as monetary compensation and restrictions, leading to reconciliation and acceptance. The mechanism is voluntary and relies on persuading the victim’s group to renounce revenge, and thus restore the necessary balance without further violence (Yanai & Adwi, 2016). The tribal rules do not distinguish between criminal and civil offenses and do not focus on punishing the person who commits the offense (Yanai & Adwi, 2016). Thus unlike the Western approach, even murder and bodily injury are not conceptualized as criminal acts but as civil damage. A dispute ends with revenge exacted from anyone in the perpetrator’s blood money group or through a sulh that usually includes a monetary arrangement accepted by the victim’s group (Tsafrir, 2006). The starting point of the sulh is that the victim’s group has a basic right of revenge against the attacker’s group, including as a way of restoring the previous balance of power. Recognizing this right, the sulh seeks to avoid revenge on the attacking group and does not focus on defending the victim. It is a mechanism that looks to the future, in an encounter between the blood money group of the perpetrator and the blood money group of the expected next perpetrator. In other words, it is adopted by societies whose members believe that revenge is a proper way to settle disputes, and who will use this method if no other monetary or suitable arrangement is agreed on.

Although the underlying principle of sulh is group revenge, which contradicts the state’s laws and values, the mechanism enjoys wide public support, even among enforcement and legal systems in Israel, where it is regarded as an expression of legal pluralism. In 1997, with police encouragement, a sulh committee was set up in Baqa al-Gharbiyye, in view of the many disputes between individuals and clans. The police then encouraged victims of minor offenses to turn to the sulh committee instead of criminal proceedings. In the case of more serious offenses, they opened a criminal file, but also notified the sulh committee, to try to calm the atmosphere. The police brochure describes cooperation between the sulh committee and the police as a positive factor that increases the local public’s trust in the police (Rapaport ben Hamo, 1999). The guidelines of the State Attorney also refer positively to the sulh (State Attorney Directive, 2018).

Courts likewise sympathize with the tendency to sulh agreements (Tsafrir, 2006). The President of the Haifa District Court saw the sulh as a positive means of recognizing the status of the Arab minority as a collective in Israel, and of strengthening its trust in the court system. Other rulings stated that it encouraged peaceful means of conflict resolution, prevented public violence, and helped to reduce the workload on the courts (Shapira, 2016).

The sulh mechanism is sometimes used during legal proceedings, as a factor to reduce criminal penalties and to assess the danger posed by the offender. However, this use is based on a fundamental error in understanding the mechanism. The purpose of sulh is to stop the injured group from taking revenge on the offending group. It therefore deals with the risk to the offender and his group, irrespective of the offender’s dangerous character. Participation in the sulh, therefore, is not an indication of the accused’s good behavior or measure of the risk he will re-offend, but of the reduced chance that he or any member of his blood money group will be attacked.

Indeed, some judges have reservations about the sulh due to the difficulties it causes (Tsafrir, 2006; Mugrabi, 2019). Sometimes the sulh agreements include a demand for non-cooperation with the legal authorities (Basel Rian v. State of Israel, 2021). Encouraging the sulh maintains the community’s hostile attitude and alienation toward the state and discourages acceptance of its laws (Yanai & Adwi, 2016, p. 53). Police attempts to find alternative ways to avoid conflict led to insufficient police involvement in society and lack of trust (Mugrabi, 2019), with clear preference for the tribal system over the state system (Yahel & Abu Ajaj, 2021).

Moreover, sulh creates inequality before the law in the efforts to eradicate crime. “It sends a double message to the Arab population on the treatment of crime and violence. A policy that allows crime to be resolved within the community without interference is a policy that indirectly encourages crime and violence” (Totari-Jubran, 2021, sec. 4). By preserving the tribal social norms, the sulh also exacts a heavy human price of blood vengeance, flight, and physical exile of family members from their homes for fear of revenge, as well as a high economic price and many years of living in fear (Mosko, 2021; Katushevsky et al., 2023).

Nachmias and Meydani (2019) referred to the importance of defining consistent rules of the game for maintaining public order, and the importance of having all the tools for enforcement in the hands of the state. Support for the sulh interferes with these rules. Indeed, in the short term it has the benefit of calming unrest and providing a recognized response to a communal circle wider than the victim-offender circle, but in the long run it bolsters tribal mechanisms of enforcement and conflict resolution based on violence and the right to revenge, while rejecting the principles of the rule of law and state enforcement mechanisms.

Conclusion

This study highlights the existence of tribal governance in the Negev, with its own mechanisms, rules of conduct, and effective enforcement system, which are different from state governance means and obeyed by extensive portions of the Bedouin population. The research also shows that there are interfaces between the tribal system and the state system, linked directly and indirectly to the issue of national and personal security. Significantly, over the years, policymakers in Israel have helped to strengthen Bedouin tribal governance and weaken state governance. Indeed, there are areas where state governance has, by action or by omission, adopted a policy that reinforces tribal governance, even when it contradicts the state laws and values of human rights that it proclaims.

Specifically, the research shows how tribal allegiance has been adopted in the Israeli ID card, while the state’s laws are not exactly implemented with respect to official identity documents. The result is that tens of thousands of Bedouins belong to tribal frameworks without an address, which makes it hard to locate them. Moreover, hundreds of thousands of dunams of land in the Negev are de facto controlled by tribal rules of how they can be used, who can enter them, and what can be built there, with no connection to the state laws. In addition, the state gives incentives to polygamy, although the practice is contrary to its laws, its values, and its obligation to protect human rights, with the emphasis on the weaker groups of women and children. Finally, the tribal method of resolving disputes based on the use of force and revenge highlights the failure represented by its support among institutional elements such as the police and the courts. The basis of tribal governance runs completely counter to the state’s concept of its exclusive right to use force in the resolution of disputes, and contravenes its values and laws, which are opposed to collective responsibility and punishments.

The overriding conclusion is that Bedouin tribal governance currently takes precedence in the Negev over state governance, as seen by its norms of conduct and control of most areas of life. Bedouin governance has been recognized and fostered by the state over many decades and is a central factor shaping not only the fabric of relations within Bedouin society, but also many of its attitudes to the state. The combination of a young population that has doubled in size within twenty years, multitudes of clans, and shrinking space in towns, as well as tribal norms that permit the use of force have led to rising tensions. Individuals acquire weapons for self-defense, as a show of power, and for deterrence, and to ensure that when necessary, the clan will be in a strong position against its enemies. The growing number of available weapons contributes to further escalation. Although most violent clashes and shooting incidents occur in and around Bedouin localities, sometimes they occur in other places, mainly on roads, with repercussions for relations between Jews and Bedouins in the Negev.[29]

The implementation of state governance has a price—a consequence of the centrality of the tribes and their deep roots, many years of fostering tribalism, and a lack of government interest in the Negev. However, a continuation of the present approach, characterized by isolated and partial promotion of issues and the pervasive desire to maintain calm, ultimately damages the strength of the Israeli state. Deep-rooted Bedouin tribal governance on the one hand and weak state governance on the other hand have brought the Negev to a problematic point. The State of Israel must take a strategic decision to stop fostering Bedouin tribal governance and start implementing its laws and values in the Negev.

Based on these conclusions, a number of directions for action are proposed:

- State symbols and institutions must be present and noticeable in Bedouin areas, with adequate services provided to their residents.

- The government must enforce the laws of land, planning, and construction by completing the process of land registration in the Negev. The state cannot ignore the law. If it believes that the law is not suitable, it has to change it by legislation. It must exercise its control over land through the means available to it.

- The government must strengthen the state’s enforcement mechanisms. The police, the courts, and other relevant entities should avoid explicit and implicit encouragement of the tribal sulh process for handling violent incidents in the Negev. The courts must reject arguments in favor of a sulh, in particular, as a means of reducing penalties.

- The Ministry of the Interior should implement the law in full and order an amendment of the ID registration of tens of thousands of Bedouins, so that their address appears in the geographic coordinate system instead of the tribal name. This means of identification is available in every cellphone.

- All branches of government, with the emphasis on the Israel Land Authority and the Development and Settlement Authority for Bedouins in the Negev, must stop allocating land by the number of wives. The state must also implement all the mechanisms intended to combat polygamy, according to the findings of reports on this subject.

- There are gaps in the knowledge and understanding of institutional entities about aspects of Bedouin society and tribal tradition. This leads to generalizations and simplification, and to decisions that ignore the long-term implications. There is therefore a need for in-depth training for local and national officials engaged in Bedouin affairs, particularly law enforcement.

******************

The author wishes to thank Adv. Noa Reichel for her assistance.

References

Abu-Rabia, A., Salman, E., & Scham, S. (2008). Polygyny and post-nomadism among the Bedouin in Israel. Anthropology of the Middle East, 3(2), 20-37. https://doi.org/10.3167/ame.2008.030203

Abu-Rabia, A. (2018). Between tribal custom and Islam: The sulh institution in Bedouin society. In M. Hatina & M. Al-Atawneh (Eds.), Muslims in the Jewish state: Religion, politics, society (pp. 260-273). Hakibbutz Hameuhad [in Hebrew].

Aburabia, R. (2022). Within the law, outside justice: Polygamy, gendered citizenship, and colonialism in Israeli law. Hakibbutz Hameuhad [in Hebrew].

Adler, S. (1995). The Bedouin woman and income support in the polygamous family. In P. Radai, K. Shalev, & M. Liban-Koby (Eds.), Status of women in society and in law (pp. 133-145). Shocken [in Hebrew].

Al-Aref, A. (2000). History of Beer Sheva and its tribes: Bedouin tribes in the Beer Sheva region (M. Kapeliouk, trans.). (Reprint) Ariel [in Hebrew].

Al-Humaidhi, H. (2015). Ṣulḥ: Arbitration in the Arab-Islamic world. Arab Law Quarterly, 29(1), 92-99. https://doi.org/10.1163/15730255-12341291

Al-Jabassini, A., & Ezzi, M. (2021). Tribal “sulh” and the politics of persuasion in volatile southern Syria. European University Institute. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2870/547211

Al-Krenawi, A. (1999). Attitudes to polygamy in Bedouin society in the Negev: Comparison of attitudes between teenagers and adults. Reshimot BeNose HaBedouin, 31, 16-35 [in Hebrew].

Al-Krenawi, A., & Slonim-Nevo, V. (2005). Polygamous and monogamous marriages: Effects on the mental and social situation of Bedouin Arab women. In R. Lev-Wiesel, G. Tsvikel, & N. Barak (Eds.),“Guard your soul”: Mental health of women in Israel (pp. 149-168). Ben-Gurion University of the Negev[in Hebrew].

Al-Krenawi, A., Graham, J. R., & al-Krenawi, S. (1997). Social work practices with polygamous families. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 14(6), 445-458. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024571031073

Ben Ari, Y. (2002). National security: Basic concepts and their implementation. In H. Efrati (Ed.), Introduction to national security (pp. 36-44). Broadcast University[in Hebrew].

Ben Baruch, Y., Binyamin, A., & Linder-Kahen, N. (2018). Dancing at every wedding: Report on polygamy in Israel—the situation and recommendations. Regavim. https://bit.ly/3JwhjGc[in Hebrew].

Ben-David, Y. (2004). The Bedouin in Israel: Social and land perspectives. Land Policy and Land Use Research Institute, Jerusalem Institute of Policy Research[in Hebrew].

Bevir, M. (2013). Governance: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Carmon, A. (2009). Reinventing Israeli democracy: Plan to amend governance in Israel. Israel Democracy Institute [in Hebrew].

Civil Appeal 4220/12, al-Uqbi et al. v. State of Israel. (2015). Psakdin 2015 (2), 6779. https://bit.ly/3wPwJhf [in Hebrew].

Coppedge, M. (2001). Party systems, governability and the quality of democracy in Latin America. Paper prepared for presentation at the conference on Representation and Democratic Politics in Latin America. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 7–8 June. https://bit.ly/3Hu7PIW

Criminal Appeal 6496/21, Basel Rayan v. State of Israel. (2021). Takdin 2021 (4). 12011 [in Hebrew].

Curiel, I. (2021, September 26). Gunshot from Tel Sheva hits houses in Omer: “We’re sitting ducks. Pity for the police.” Ynet. https://bit.ly/3wRVsSh[in Hebrew].

Dekel, T. (2023). Criticism, development, and politics of knowledge in planning Bedouin settlement in the Negev. In H. Yahel & A. Galilee (Eds.), Bedouins in the Negev: Tribalism, politics, and criticism (pp. 55-84). Herzl Institute for the Study of Zionism, Haifa University [in Hebrew].

Dror, Y. (2005). Letter to an Israeli Jewish-Zionist Leader. Carmel [in Hebrew].

Dupret, B. (2006). Legal traditions and state-centered law: Drawing from tribal and customary law cases of Yemen and Egypt. In D. Chatty (Ed.), Nomadic societies in the Middle East and North Africa: Entering the 21st century (pp. 280-301). Brill.

Gohar, Y. (2021, February 25). Non-governance, its punishment and price. Globes. https://bit.ly/3JzNuET[in Hebrew].

Goldberg Commission report on regulating Bedouin settlement in the Negev. (2008, December 11). Development and Settlement Authority for Bedouins in the Negev. https://bit.ly/3jn69ci[in Hebrew].

Greenzeig, A. (2022, January, 302). The Ministry of Justice is silent over qadis who authorize polygamy contrary to the law. Globes. https://bit.ly/3x0ovTL[in Hebrew].

Harel-Fisher, E. (2020). Democracy, governability, government corruption, and public discourse. In G. Talshir (Ed.), Governability or democracy? The struggle over the public interest and the rules of the Israeli political game (pp. 109-132). Resling [in Hebrew].

Ifergan, S. (2021, October 11). Another night of gunfire in the south: “They’ve been shooting at us for six months already and the police do nothing.” Mako. https://bit.ly/40qARBV[in Hebrew].

Justin, J. (2020). Muslim alternative dispute resolution: Tracing the pathways of Islamic legal practice between South Asia and contemporary Britain. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 40(1), 48-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602004.2020.1741170

Kaplan, R. (2010). Regulation. Mafteach 1, 179-212. https://bit.ly/3YeR5ML[in Hebrew].

Katoshevski, R., Tamari, S., Dinero, S., & Karplus, Y. (2023). Urban tribalism: Structure, function, and residency in Bedouin towns in the Negev. In H. Yahel & A. Galilee (Eds.), Bedouins in the Negev: Tribalism, politics, and criticism (pp. 23-54). Herzl Institute for the Study of Zionism, Haifa University [in Hebrew].

Kedar, A., Amara, A., & Yiftachel, O. (2018). Emptied lands: A legal geography of Bedouin rights in the Negev. Stanford University Press.

Khadduri, M. (2012). Sulh. In P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, & W. P. Heinrichs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7175

Kooiman, J., Bavinck, M., Chuenpagdee, R., Mahon, R., & Pullin, R. (2008). Interactive governance and governability: An introduction. Journal of Transdisciplinary Environmental Studies, 7(1), 1-11. https://bit.ly/3l3OjM3

Kymlicka, W. (1995). Multicultural citizenship: A liberal theory of minority rights. Clarendon Press.

Lapidot-Firilla, A., & Elhadad, R. (2006). Forbidden yet practiced: Polygamy and the cyclical making of Israeli policy. Center for Strategic & Policy Studies.

Levi-Faur, D. (2012). From "big government" to "big governance"? In D. Levi-Faur (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Governance (pp. 3-8). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199560530.013.0001

Lyon, A. (2018). Review of Shades of sulḥ: The rhetoric of Arab-Islamic reconciliation, by Rasha Diab. Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 21(4), 737-739. https://doi.org/10.14321/rhetpublaffa.21.4.0737

Maron, A. (2012) Privatization or reformation of the state? The case of the Wisconsin Plan in Israel. Social Security, 90, 51-77 (additional publication in Edition 93, pp. 163-191). https://bit.ly/3Jpyoli[in Hebrew].

Meydani, A. (2015). The vision of Israeli governance. Tel Aviv University and Israeli Center for Citizen Empowerment. https://bit.ly/3YnyJZP[in Hebrew].

Mintzker, U. (2015). The Janabib in the Negev highland: Tribe, territory, and recognized group. (Doctoral dissertation). Ben Gurion University of the Negev [in Hebrew].

Mosco, Y. (2021, November 18). “Tribal law comes before state law”: The murderous tradition and the mass brawl in Soroka. N12. https://bit.ly/3lvArua[in Hebrew].

Mugrabi, A. (2019). Sulh: The practice of traditional Arab ADR in Northern Israel (essay for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science). Tulane University. https://bit.ly/3DDTEzZ

Nachmias, D., & Meydani, A. (2019). Public policy: Foundations and principles. Open University of Israel [in Hebrew].

Offe, C. (2009). Governance: An "empty signifier"? Constellations, 16(4), 550-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.2009.00570.x

Othman, A. (2007). "And amicable settlement is best": Sulh and dispute resolution in Islamic law. Arab Law Quarterly, 21(1), 64-90. https://doi.org/10.1163/026805507X197857

Powell, W. W. (1990). Neither markets nor hierarchy: Network forms of organization. Research in Organizational Behavior, 12, 295-336. https://stanford.io/3wPkz8d

Rabi, U. (Ed.). (2016). Tribes and states in a changing Middle East. C Hurst & Co.

Rapaport Ben Hamo, H. (1999). Sulh Committee. Marot HaMishtara: Israel Police Journal, 172, 32-33, 46 [in Hebrew].

Research and Information Center. (2014). Polygamy in the Bedouin population in Israel: Update. The Knesset. https://bit.ly/3YQzgng[in Hebrew].

Research and Information Center. (2022, February 19). Multiple marriages (polygamy): Enforcement and reporting. The Knesset. https://bit.ly/3HqlZLe [in Hebrew].

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1990). Policy networks: A British perspective. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 2(3), 293-317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692890002003003

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1996). The new governance: Governing without government. Political Studies, 44(4), 652-667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb01747.x

Shahar, I. (2018). Mediators in dispute in state-community relations: Dispute resolution among Arabs in Israel from a legally pluralistic perspective. Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research. Tel Aviv University [in Hebrew].

Shaked, A. (2016). The path to democracy and governance. Hashiloach, 1, 37-55. https://bit.ly/2sDPALc[in Hebrew].

Shapira, R. (2016). Culture and communal tradition as a tool to assist in law enforcement. In A. Yanai & T. Gal (Eds.), From wrongdoing to righting the wrong : restorative justice and restorative discourse in Israel (pp. 28-50). Magnes [in Hebrew].

Shochat, L. (2007). “Governance” and its consequences for national security. Position Paper no. 2. Center for Strategic and Policy Research. National Security College, IDF. https://bit.ly/40heNtH[in Hebrew].

State Attorney Directive no. 5.20: “Reconciliation” between accused and plaintiff in the remand process. (2018, March 26). State Attorney Directive. https://bit.ly/3Du9E7J[in Hebrew].

State Comptroller. (1967). Annual report 17 for 1966 and accounts for financial year 1965/6 (pp. 294-296). https://bit.ly/3E4CN9P[in Hebrew].

State Comptroller (2011). Abu Basma Regional Council: Provision of services and infrastructure development. Reports on local government audit for 2010 (pp. 691-759). https://bit.ly/3YMLD3N[in Hebrew].

State Comptroller (2016). Aspects of the regulation of Bedouin settlement in the Negev: Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. Annual report 66c (pp. 917-984). https://bit.ly/3jTsxKJ [in Hebrew].

State Comptroller (2021). Aspects of governance in the Negev: Introduction. Annual Report 72a: Part I. https://bit.ly/3WWsUBF[in Hebrew].

Stewart, F. (2006). Customary law among the Bedouin of the Middle East and North Africa. In D. Chatty (Ed.), Nomadic societies in the Middle East and North Africa: Entering the 21st century (pp. 239-279). Brill.

Stoker, G. (2018). Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal, 68(227-228), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/issj.12189

Summary report: Inter-ministerial team for handling the negative consequences of polygamy (2018). Ministry of Justice. https://bit.ly/2lSIv6f[in Hebrew].

Suwaed, M. Y. (2015). Historical dictionary of the Bedouins. Rowman & Littlefield.

Talshir, G. (2020). The public interest and democracy: Between governance and governability. In G. Talshir (Ed.), Governability or democracy? The struggle over the public interest and the rules of the Israeli political game (pp. 9-32). Resling [in Hebrew].

Totry-Jubran, M. (2021, February 19). The state institutionalized the institution of sulh and that contributed to the rise in violence in Arab society. Globes. https://bit.ly/3wQuiuQ[in Hebrew].

Tsafrir, N. (2006). Arab customary law in Israel: Sulh agreements and Israeli courts. Islamic Law and Society, 13(1), 76-98. https://doi.org/10.1163/156851906775275457

Von Benda-Beckmann, F., & von Benda-Beckmann, K. (Eds.). (2009). Rules of law and laws of ruling: On the governance of law (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315607139

Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. Journal of Law and Economics, 22(2), 233-261. http://www.jstor.org/stable/725118

Wimmer, A. (1997). Who owns the state? Understanding ethnic conflict in post‐colonial societies. Nations and Nationalism, 3(4), 631-666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1997.00631.x

Yahel, H. (2017). Illegal but it pays off: Allocation of plots of land in the Negev to polygamous families. Planning, 14(1), 204-211 [in Hebrew].

Yahel, H. (2018). Bedouin settlement proposals in pre and early days of the State of Israel, 1948-1949. Israel: Journal on the Study of Zionism and the State of Israel—History, Culture, Society, 25, 1-29. https://bit.ly/3HsPGLw [in Hebrew].

Yahel, H. (2019). The conflict over land ownership and unauthorized construction in the Negev. Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 6(3-4), 352-369.

Yahel, H., & Abu Ajaj, A. (2021). Tribalism, religion, and state in Bedouin society in the Negev: Between preservation and change. Strategic Assessment, 24(2), 54-71. https://bit.ly/3VkipbZ

Yahel, H., & Galilee, E. (Eds.). Bedouins in the Negev: Tribalism, politics, and criticism. Herzl Institute for the Study of Zionism, Haifa University. https://bit.ly/3Y3GQeE[in Hebrew].

Yanai, A., & Adwi, S. (2016). Tradition of settling criminal conflict: What lies between “sulh” and “restorative justice.” In A. Yanai & T. Gal (Eds.), From wrongdoing to righting the wrong: Restorative justice and restorative discourse in Israel (p. 51-75). Magnes [in Hebrew].

Yaron, R. (2002). State power and national security. In H. Efrati (Ed.), Introduction to national security (pp. 56-69). Broadcast University [in Hebrew].

Notes

[1] On the complexity of the link between liberal and multicultural countries and minority rights, see Will Kymlicka. Kymlicka (1995) points to the clash in such countries between the majority and minorities on issues of language, autonomous spaces, political representation, school curriculum, claims of land ownership, national symbols, migration, and more. He says that finding practical and defensible solutions to these issues is the biggest challenge currently facing democracy. The main research development on these issues grew in the context of post-colonialist countries (Wimmer, 1997).

[2] Online Etymology Dictionary.

[3] Since 2000 there has been extensive writing on the activity of violent non-state actors and terror organizations in the context of governance. See for example, K. Michael & O. Dostry (2018). The process of political establishment of sub-state actors: The conduct of Hamas between sovereignty and continuing violence. The Inter-Disciplinary Journal of Middle East Studies, 3, 57-90 [in Hebrew]. This subject is beyond the scope of this article. The discussion of non-state organizations focuses on processes of institutionalization that convert these organizations into sovereign governing bodies that can replace the country’s regime. In contrast, Bedouin tribalism in the Negev does not seek to destroy or replace the national government. See also K. Michael & Y. Guzansky (2017). The Arab world on the road to state failure. Institute for National Security Studies.

[4] The Academy of the Hebrew Language - meshilut.

[5] Avnion Dictionary online. According to Talshir (2020), the correct translation of governability should be mimshaliut and not meshilut.

[6] Basic Outline of Government Policy, Knesset Secretariat, May 13, 2015 [in Hebrew].

[7] For a critique of the limited nature of the discussion in Israel, see Carmon (2009), p. 18.

[8] Examples of items taken from social media: A video of young men brandishing weapons, October 7, 2021, Walla!; Attack on a vehicle at a Negev junction, April 23, 2018, Ynet; Gunfire at a cafe in Rahat employing women, April 7, 2022, Ynet [in Hebrew][.

[9] Book of Laws 466, p. 270, August 1, 1965; Book of Laws 2696, Amendment to the Population Register Law—No. 20, p. 214, February 28, 2018 [in Hebrew].

[10] MK Said al-Harumi and his partners tabled the original version, 2095/23/p on September 14, 2020, under the heading “Bill to Amend the Income Tax Ordinance (Tax benefits to localities), 5781-2020. Amendment to Section 11 of the Income Tax Ordinance.” The request was to add the words “or significant Bedouin tribes” to the definition of “Urban localities in the Negev.”

[11] Proposal 2266/24/p was tabled again on October 11, 2021. The Committee of Ministers for Legislative Affairs postponed the discussion.

[12] See for example Kedar et al. (2018).

[13] Land Law, 5729-1969, Book of Laws 575, p. 259, July 27, 1969; Ottoman Land Law, 1858, https://bit.ly/3X0ThWW [in Hebrew].

[14] Land (Settlement of Title) Ordinance, 1928. Official Gazette, June 1, 1928. Replaced by the Land (Settlement of Title) Ordinance of 1928 [New version], 5729-1969, Laws of the State of Israel [New version], p. 293, July 27, 1969, https://bit.ly/3Ht3ztl [in Hebrew].

[15] In the few cases that were heard in court, the state won. Civil Appeal 4220/12 al-Uqbi v. State of Israel (not published, May 14, 2015), and recently Civil Case 48918-02-19 (Beer Sheva District Court) Gaboa v. State of Israel (not published, January 5, 2023).

[16] Government Resolution 2491 of October 28, 2007, amended Resolution 1999 of July 15, 2007. https://bit.ly/3YjMBo1 [in Hebrew].

[17] The Public Land Law (Land Evacuation), 5741-1981, Book of Laws 1005, p. 105, February 12, 1981. See S. Dana & S. Zinger. (2015). Design and Construction. Nevo [in Hebrew].

[18] The Authority was set up by virtue of the Planning and Building Law (Amendment 116), 5777-2017, Book of Laws 2635, p. 884, April 25, 2017.

[19] According to the Planning and Building Laws, which came into force already in 1921, it is forbidden to build without a permit from the authorities. Such buildings will be demolished, and the perpetrator punished.

[20] Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, General Recommendation 21, Equality in Marriage and Family Relations, UN CEDAW, 13th Session, UN Doc. A/47/38, (1994), at para.14.

[21] More precisely—polygyny, a specific incidence of polygamy involving marriage between one man and a number of women at the same time.

[22] The Convention on the Rights of the Child, Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child: Djibouti, UNCRC, UN Doc. CRC/C/15/Add.131 (2000) at para. 34.

[23] S. Liebowitz-Dar (2005, October 12). “Children are joy,” interview with Abu Arar, Maariv [in Hebrew].

[24] Book of Laws 864, p. 226, October 4, 1977.

[25] Family case (Beer Sheva) 55724-09-16, Anonymous v. Attorney General (unpublished).

[26] As of February 7, 2022, 45 indictments had been filed for multiple marriages; 10 of them ended in imprisonment and other penalties.

[27] The Negev Land Acquisition (Peace Treaty with Egypt) Law, 5740-1980. Book of Laws 179, August 3, 1980.

[28] Summary Report (2018), p. 108, footnote 213.

[29] Tension has led to the rise of self-defense groups such as Sayeret Barel (Barel Patrol).