Strategic Assessment

Propelled by changes in the information environment, the nature of war, and social norms and values, recent years have seen increasing public exposure of the Israeli intelligence community. Operations, capabilities, and even intelligence information are reported frequently in the media. The disclosure of intelligence information specifically has been shown to have strategic value, including in terms of creating deterrence and international legitimacy, as well as domestic value, in contributing to important democratic values such as transparency and oversight of the government. However, such exposure also carries risks—not only to sources, but also of adverse effects in the form of weakened deterrence, escalation, potential criticism and ridicule, and the politicization of intelligence. This article analyzes the opportunities and risks inherent in increased public disclosure of intelligence information by the state, and suggests possible ways for Israel to balance between concealment and exposure, including with checks and balances between intelligence units and agencies; models to assess both the damage to sources and the benefits of exposure; guidelines for working properly with the media; and enhanced public access to information and assessments.

Keywords: intelligence, deterrence, cognition, public diplomacy, Israel, Iran, Hezbollah, Gaza

Introduction

Between June 25 and mid-July 2020, a series of explosions occurred

in the vicinity of sensitive installations throughout Iran. On July 5, the New York Times quoted a

senior intelligence source in the Middle East, who attributed responsibility

for one of the explosions—the sabotage of the centrifuge manufacturing facility

at the Natanz nuclear site—to Israel. As a result of the article, former

defense minister Avigdor Liberman accused a senior Israeli

intelligence official of the disclosure, which, in his view, is a flagrant

violation of Israel’s traditional policy of ambiguity.

This episode reignited the public discussion of the cost-benefit

balance in disclosing intelligence, and the dilemma between the need for silence

surrounding intelligence work, and intelligence secrets in particular, and the

security, diplomatic, and political goals that can be achieved through information

sharing. This debate gained new momentum in the Israeli public in recent years,

in view of the increasing trend of disclosure. On one side, there are those who want to warn

against the “stripping down” of the Israeli intelligence community, which

carries a risk to valuable intelligence assets and, according to the proponents

of this argument, is derived from irrelevant considerations such as building up

political capital among internal public opinion, or public relations for

intelligence organizations. In contrast, some argue the political-security

benefit of exposing secret intelligence data, and contend that achieving

high-quality intelligence is not a goal in and of itself, but rather a tool

that is subject to policy considerations. This position was reflected by a senior political official,

who responded to the criticism of the improper use of intelligence information,

stating, “We do not have intelligence that has a state, but a state that has

intelligence.”

Secrecy has always gone hand in hand with intelligence work, and has even come to define it. The secrecy that shrouds the intelligence community and its output is necessary in order to protect the sources and work patterns that help uncover information about the opponent.

This article focuses on state disclosures of intelligence, i.e., the

public disclosure of up-to-date intelligence information on opponents or allies

in the international sphere, by and with the approval of government and

intelligence and security agencies. The divulgence of information on the activity

of Israel’s own military and intelligence agencies, or about their

capabilities, is therefore outside the purview of this paper, as are statements

or leaks to the press that have not been approved by the authorized entities. As

such, the article will analyze the opportunities in the state’s disclosure of

intelligence vs. the risks inherent in this practice, and will suggest possible

ways to balance between concealment and exposure in Israel’s foreign and

defense policy.

Benefits in Public Intelligence Disclosure

Secrecy has always gone hand in hand with intelligence work, and

has even come to define it. The secrecy that shrouds the intelligence community

and its output is necessary in order to protect the sources and work patterns

that help uncover information about the opponent.

In Israel, intelligence secrecy is even more important. Given that

Israel is surrounded by enemies and is constantly under security threat, its

security concept dictates that secrecy serves more than protection of the

sources that provide early warning. Rather, secrecy also serves the principle

of surprise that is essential for successful preventive attacks against

emerging threats, as well as the principle of ambiguity that helps reduce the

risk of a counter-response and military escalation. As such, decision makers

and people in the Israeli defense establishment and intelligence community are

used to working under a cloak of secrecy, and generally avoid revealing state

secrets. Moreover, the secrecy surrounding their work and their occupation with

issues involving state security in general provides them with a monopoly on

information and knowledge and, as a direct result, much influence on decision making.

Therefore, the Israeli intelligence community traditionally views exposure as damaging

to its work, and in general maintains its distance from the media and denies it

information. Due to “the sanctity of security” and the internalization that

defense considerations overcome democratic considerations, the shroud of

secrecy surrounding Israel’s foreign and defense policy has won broad

understanding and legitimacy among the public—which even considers itself “a

partner to the secret.” All this has led sociologists and political scientists

to define Israel as a “secretive state” that

maintains a “culture of secrecy.”

However, recent years have seen an increasing emergence of the

Israeli intelligence community into the public sphere. Operations,

capabilities, and even intelligence information are reported frequently. Junior

and senior members of the intelligence community, whether in active service or

retired, appear in the media more than ever before (even if their faces are

blurred) in order to share their experiences and praise their units’

capabilities.

To be sure, in many cases, there is strategic value in disclosing intelligence capabilities and information. The

advantages of disclosure include:

Thwarting and disrupting adversarial

activity: Adversaries operating under a

shroud of secrecy are particularly sensitive to the exposure of intelligence

information about them, be they countries like Iran as it strives to attain military

nuclear capability, or violent non-state actors such as Hezbollah in Lebanon or

Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza, which are working to undermine the sovereign

or dominant power in their operational sphere—the State of Lebanon and Hamas,

respectively—and therefore need to hide from that power. The public disclosure

of intelligence information can serve as a powerful weapon, able to extract a

price from such adversaries, whether in uncovering an operational secret (a

project, unit, or site); negating the element of surprise in a given action,

and thereby disrupting it; or embarrassing the adversary in its domestic public

opinion. In the era of the campaign between wars (CBW), which relates to the

weakening of the adversary and disruption of its operations below the threshold

of war, disclosing intelligence may sometimes achieve an effect similar to

dropping a bomb. A prominent example of this is the campaign that Israel is

waging against Hezbollah’s attempts to manufacture precision-guided missiles in

Lebanon, which relies to a great extent on the disclosure

of facilities tied to this

project. The disclosure essentially “consumes” those facilities and makes it

necessary for Hezbollah to move them to an

alternative site, thereby causing interruptions and delays in the project.

Signaling determination and maintaining deterrence:The judicious disclosure of intelligence can signal to an adversary about the disclosing party’s determination; it serves as a preliminary step before force is used, with the aim of deterring the adversary from taking belligerent action. For instance, in April 2019, shortly before Memorial Day and Independence Day celebrations and the Eurovision song contest in Tel Aviv, the IDF Spokesman distributed a picture of senior Islamic Jihad commander Bahaa Abu al-Atta, and pinned responsibility for rocket fire toward Israel on him. He thereby warned Abu al-Atta that continued rocket fire at a time that was sensitive for Israel could cost him his life—which is what actually happened later that year, in November. In addition, exposing concealed secrets infuses in the adversary a sense of penetration—the understanding that it is exposed to foreign intelligence espionage. This acknowledgment calls for close investigation, which can in turn crack the trust between those who are party to the secret, damage morale, and dampen the excitement in taking strong belligerent actions such as war, in view of the recognition of intelligence inferiority. The press briefing held at the IDF Northern Command in July 2010 is a clear example of this logic, when in an unprecedented briefing, an aerial photograph of the village of al-Khiam in southern Lebanon was shown. The Hezbollah deployment was marked on the photograph, including weapons caches, command posts, and underground bunkers. A few months later, in March 2011, the Washington Post published a map of southern Lebanon with similar labels, based on intelligence that was obtained by the IDF. Then-GOC Northern Command—and later IDF Chief of Staff—Gadi Eisenkot testified that in his view, the goal of publicly using intelligence, is “to empower our image in the eyes of the enemy, and to terrify it.” 1 Therefore, disclosure can contribute to deterrence, whether on a pinpoint basis, or in a more prolonged and cumulative sense.

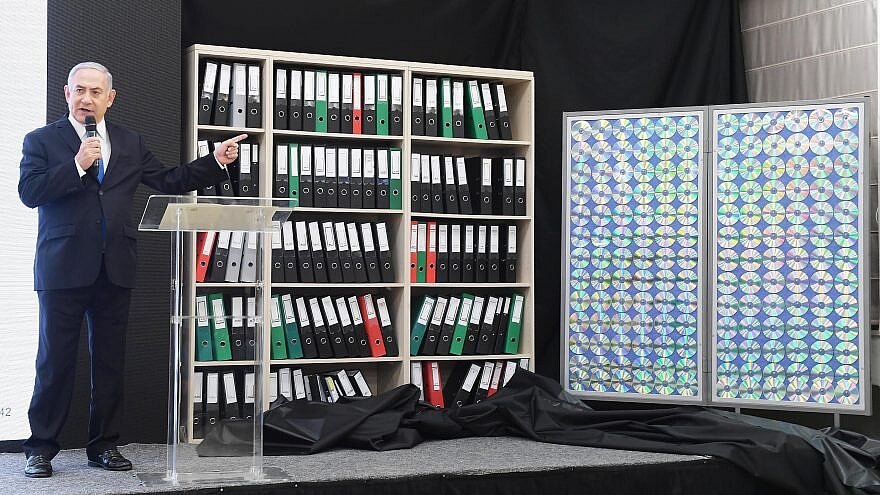

Legitimizing Israeli policy and

delegitimizing the adversary in international public opinion: Disclosing intelligence information, particularly if it is done

with the proper timing and context, can affect the adversary’s image and tilt

international decision making—for example, in April 2018, with the exposure of materials

brought by the Mossad from the Iranian nuclear archive just prior to US

President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the nuclear agreement. Similarly, at

the UN General Assembly in September 2018, Prime Minister Netanyahu revealed the “secret

atomic warehouse” in the outskirts of Tehran, and called on the Chairman of the

International Atomic Energy Agency to send inspectors to the site. This also

happens from time to time with the exposure of Hezbollah activity

in southern Lebanon in advance of UN Security Council discussions dealing with

extending or expanding the UNIFIL mandate. Israel is clearly not the only

country trying to influence global public opinion and blacken its adversaries

in the international sphere by disclosing intelligence. This past May, in the

midst of the Covid-19 crisis, a report written by the Five Eyes intelligence

group (comprising the US, the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) was leaked to the Australian media

blaming China for covering up and destroying evidence of the spread of the

disease.

The public’s right to know: In contrast with other benefits, which generally feature the partial disclosure of secret information at a time chosen to serve a defined political-security purpose, the broad, methodical, and periodical public disclosure of intelligence information and assessments may be beneficial for democracy. Through exposure to security information, the public, the media, and Knesset can supervise and influence government policy. However, broad intelligence disclosure is no small matter. American intelligence researcher Harry H. Ransom discussed the dilemma, noting that “While secrecy is inconsistent with democratic accountability, disclosure is incompatible with effective intelligence operations.” However, in tandem, legislators, political scientists, and social activists are proposing solutions to reconcile the tension between the values, including replacing the worldview that asks, as a working guideline, what can be exposed, with a worldview that asks what must be classified. There is also the effort to instill a norm of government or parliamentary investigations that deal only after the fact with security and intelligence episodes, thereby protecting covert work in real time, but also instilling in operatives an awareness of supervision and responsibility. In Israel, key messages from the annual intelligence reviews are sometimes exposed, but only after senior intelligence officials review them and choose in advance what information and assessments to share with defense correspondents and commentators, who in the end control the message that is sent to the general public. This practice, which has evolved in recent years, is different from the common practice in Western countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, where the government or the intelligence agencies themselves publish written intelligence assessments, sometimes accompanied by public announcements, in a comprehensive manner that includes discussion of the entire range of threats.

Risks in Public Intelligence Disclosure

Alongside the benefits of disclosing intelligence, after years of

Israeli policy making frequent public use of secrets, inherent risks and costs of

such a policy are evident.

Incurring a cumulative risk to

sources and methods: This means

not only risking the burning of sources that have helped uncover the specific

information that was disclosed, but also cumulative damage to reputation and

the ability to recruit future sources in view of the concern that disclosure

will put them in mortal danger.

Removing ambiguity and risking a

response: Most of the recent disclosures

have been made through Israeli media or public announcement on the part of

senior Israeli officials. This is as opposed to anonymous leaks to foreign

media—Arab or Western—that were common until not long ago in cases where Israel

wanted to signal a particular threat or put matters in the proper perspective

in the international discourse, while limiting the risk to sources. Thus, the disclosures

attributed to Israel place it clearly as the party challenging its adversary in

a way that limits deniability and invites counteraction.

Reputation management as an

imperative: If a party that tends to disclose

information remains silent in a particular case, its silence may be interpreted

by the adversary as evidence of a weak point or intelligence blindness. Alternatively,

it may be interpreted as restraint due to the ramifications of disclosing the

issue in a case where it may embarrass that party or put it in conflict with

other core interests. As such, a kind of commitment to the continued disclosure

of intelligence information is created.

In contrast, continued disclosure

may harm deterrence, if the disclosure

itself does not incur a cost for the adversary or lead to diplomatic or

military action. Thus, relying solely on disclosure may be interpreted as

restraint on the part of the disclosing party from taking steps with greater

potential risk, and as a signal to the adversary of a de facto “immunity area.”

Instead of achieving the expected political, security, or

political effect, disclosure may achieve the opposite effect. For

instance, disclosure may actually be construed as less threatening, or

fear-inducing than maintaining secrecy and ambiguity, and it may also decrease

the adversary’s level of uncertainty. Domestically, it may actually lead to

criticism of carelessness, negligence, or lack of ethics. Consider, for

example, the exposure of the Mossad’s role in purchasing medical equipment for

the struggle against the Covid-19 pandemic, and particularly bringing in

testing kits, which later turned out to be incompatible with the medical task. The

exposure led to a wave of criticism and ridicule at the expense of the

organization on television programs

and social media, and in the

end to some extent caused harm to the organization’s image (and not only in

Israel).

Politicization: The changing norm in relation to intelligence secrecy, and the transition to systematic disclosure, may subsequently lead to political considerations interfering in intelligence work, and to repeated public manipulation of intelligence information and assessments, with the aim of influencing public opinion in Israel. Thus, the political echelon may demand more intelligence information that will support a policy it wishes to advance, and senior intelligence officials may produce more “satisfying” information and designate it for disclosure the more their success is measured publicly. Over time, the politicization of intelligence may erode the reliability and prestige that give intelligence organizations in Israel the tremendous influence they have over policymaking. The case in which Prime Minister Netanyahu disclosed additional nuclear sites in Iran during a press conference about a week before the second round of elections in 2019 proves how narrow the line is between public use of intelligence information for diplomatic and security needs and its use for political purposes. While a source in the Prime Minister’s Office argued that the disclosure was made at the recommendation of professional echelons, the opposition condemned the “profiteering from state security” to benefit the election campaign. Former senior intelligence officials also believe that most of the intelligence disclosures of recent years—including the disclosure mentioned above—do not serve the national interest, but rather the personal political interests of senior politicians and intelligence officers. 2 In this context, the experience of the United States and the United Kingdom prior to the military invasion of Iraq in 2003 is instructive. The uncompromising effort of the political echelon to convince domestic and international audiences of the need for a military campaign against Saddam Hussein’s regime with the false claim that it was developing nonconventional weapons led to destruction of intelligence work and the routine publication of partial and unfounded information, in a way that seriously damaged public trust in American and British intelligence.

Policy Recommendations

The change in attitude toward intelligence among Israel’s top political-security

echelons is inevitable. The transition to increased exposure and disclosure

reflects the deep changes in the global information and communications

environment, which features information overload and a tendency toward greater

exposure as a condition for increasing influence; in the nature of conflicts,

which carry serious asymmetry that generally acts to benefit the weaker side

and is in any case of limited purpose to the stronger side; and in the

political and societal values in Israel.

Occasionally, as shown by the list of potential risks, offering an inch may actually lead to giving a mile and exposure to a different kind of risk.

However, even if the state authorities believe that intelligence disclosure

serves the national interest, and that while baring a little they conceal much

more, it appears that the opposite is the case. Occasionally, as shown by the

list of potential risks, offering an inch may actually lead to giving a mile and

exposure to a different kind of risk. Accordingly, certain practices may

minimize the potential damage from increased disclosure and ensure a balanced

policy:

1. Maintaining checks and balances within the military and the intelligence agencies, and between(them. In this context, those in charge of the military and intelligence campaigns of deterrence, disruption, and influence on cognition, who recommend information, capabilities, and operations for disclosure, must be different from those entrusted with developing and protecting sources and assessing the risks due to exposure. If the same unit is entrusted with sources and information protection on the one hand, and with influence and psychological operations on the other, it may create a tendency toward the operational side whereby that unit is measured, and which gives it its prestige and relevance.

2. Ensuring debate before disclosure, in order to allow for a variety of voices and considerations to be heard, map out all damaging scenarios that may develop in the context of the concrete disclosure, and thereby avoid a boomerang effect. Moreover, within the organizations themselves, standard operating procedures can be created such as having all people relevant to the process—including source development personnel, information security personnel, analysts, and spokespeople—sign their dis/approval of the disclosure on an official document that will give them the opportunity to present reservations and make conditions regarding the volume of information to be released, the platform, and the timing.

3. Developing models for assessing damage to sources and methods, both on a short term pinpoint basis around concrete disclosures, and in the long term to assess cumulative damage. In the absence of a complete picture of the pieces of information held by the adversary’s counterintelligence agencies, the ability to assess specific or cumulative damage to sources and methods as a result of an intelligence disclosure is very limited. 3 In other words, when Israel publicly releases intelligence information, it does not know with sufficient certainty whether the disclosure completes the puzzle for the adversary’s counterintelligence and helps it block leaks that provide it with vital information. This difficulty must be addressed by constantly strengthening the understanding of the adversary’s counterintelligence efforts and its leading assessments regarding Israel’s intelligence assets and modus operandi. Accordingly, cover stories for intelligence disclosures can be created and fraudulent information planted with the aim of strengthening misleading beliefs and distracting the adversary from the real information channels. Furthermore, creative tests and measures to assess the cumulative damage to sources must be developed, with the correlation between intelligence disclosures and damage to intelligence assets found.

4. Developing models to measure the success of intelligence disclosure in achieving abstract goals , such as deterrence, disruption, and legitimacy. In order for the decisions between concealment and secrecy on the one hand and exposure and design of adversary cognition on the other to be balanced, they must be based as much as possible on empirical data. In this context, measures based on qualitative and quantitative analysis of discourse and texts must be built to help assess the effect of disclosure on abstract terms such as deterrence and legitimization. For instance, compartmentalization is one of the expressions of disrupting the adversary’s activity, which is achieved by disclosing intelligence. Disclosure as evidence of an information leak in the organization can lead to damage to trust between the organization’s members and to the creation of compartmentalization between units and operatives. While raising the walls within the organization lowers the risk of information leaks, it also disrupts and confuses the organization’s routine and emergency behavior and thereby impairs its efficiency. A measure for assessing compartmentalization among adversaries, which also correlates between disclosure and compartmentalization, can help in decision making regarding intelligence disclosure.

5. Directing operations and developing sources that are initially intended for disclosure.

6. Training senior officers and managers in intelligence agencies in how to act vis-à-vis the media. Since the public use of intelligence is currently considered part of the toolbox for managing political-security campaigns, content to encourage familiarity with the world of open communication can be integrated into training programs, including the opportunities in relations with the media and the use of various media outlets, alongside the costs and risks inherent in them.

7. Encouraging the government and intelligence agencies to present their assessments in a broad and periodical manner for the good of the public. Reports such as these must be as comprehensive and well-founded as possible, and must ask—as a working guideline—what information must be classified and protected, rather than what information can be disclosed. This is similar to the censorship model in existence since the Shnitzer case in the Supreme Court (1988), when it was determined that freedom of expression is subordinate to state security only where there is “proximate certainty of material damage to state security.” Thus, the public discourse will be as knowledge-based and objective as possible, and not subject to manipulation on the part of parties with other interests.

Conclusion

In the age of information and social media, when information campaigns and contests over narratives are intensifying, and while the concept of truth is challenged by phenomena such as fake news, the publication of high-quality reliable information concerning foreign and defense matters on the part of state authorities can have great benefit, both in advancing political interests and in strengthening the foundations of democracy. This is even more the case when talking about a country like Israel that struggles every day on a number of fronts for its security and the justness of its path. However, there must be a policy that balances between disclosure on the one hand, and concealment and protection of intelligence assets on the other, since when it comes to intelligence matters, it is best to bare a little and conceal even more.

Footnotes

- (1) Interview between the author and Lt. Gen. (ret.) Gadi Eisenkot, June 4, 2020.

- (2) The author’s interviews with former senior officials in the intelligence and defense communities.

- (3) The author’s interviews with former senior officials in the intelligence and defense community.