Strategic Assessment

Recent years have seen a noticeable increase in the recourse by states and international organizations to level economic sanctions on various countries, commercial entities, financial bodies, and individuals. This trend, however, does not reflect the success rate of these sanctions, and research indicates that their chances of success are slim. The reasons for the poor success rate of sanctions regimes depend on the specific cases and the importance of the interests of the involved parties. Nonetheless, certain patterns of behavior repeat themselves in each of the countries targeted by sanctions, such as adapting the local economy to the sanctions, resisting the sanctions in the international system, and taking practical steps to bypass them. This article surveys the patterns of behavior that countries employ in dealing with sanctions, focusing primarily on tools to evade them. Looking at North Korea, Russia, and Iran as case studies, it describes the tools that help nations bypass comprehensive sanctions. These modes of behavior also illuminate how various actors perceive sanctions and how countries that impose sanctions implement and enforce them.

Keywords: economic sanctions, sanctions evasion, Russia-Ukraine war, financial sanctions, trade sanctions, sanctions circumvention, North Korea, Russia, Iran, China

Introduction

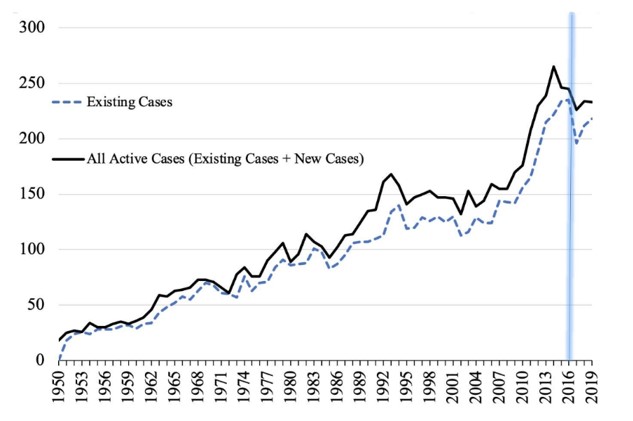

Economic sanctions are not a new tool in a nation’s toolbox. The first recorded mention of sanctions is from the fourth century BCE, when Athens imposed sanctions on the city-state of Megara, which was allied with Sparta in the Peloponnesian War. At the end of World War I, the League of Nations stressed the potential of sanctions as a nonviolent means of solving conflicts between nations (Hufbauer et al., 1985). However, the tool was used infrequently, and only expanded significantly in the past few decades. Since the 1990s, many countries, either independently or within the framework of international organizations, have tended to make widespread use of sanctions (Figure 1). Behind the greater popularity of sanctions are geopolitical changes in the aftermath of the Cold War, the increasing importance to the international community of issues such as human rights and processes of democratization, and the reluctance to use military tools to achieve political goals, which necessarily exact a heavy price (Jones, 2015).

Figure 1. Upward trends in the imposition of sanctions, 1950-2019 | Source: Yotov et al., 2021

Sanctions, however, have many disadvantages. Economic sanctions can be a burden for the country imposing them, and not just the country subjected to them (the target country) (Elliott, 1997). Comprehensive sanctions can harm underprivileged populations that have no influence in the target country, and could lead to a severe humanitarian crisis in that country, as in Iraq under Saddam Hussein, following many years under a sanctions regime (Halliday, 1999). However, one of the main drawbacks of sanctions is their lack of effectiveness; according to the accepted figure, sanctions achieve their goal only around one third of the time (Hufbauer et al., 2009). In other words, in most cases sanctions fail to achieve the goals for which they were imposed, since the target countries managed to survive despite the limitations imposed on them. Note, however, that there are differences of opinion when it comes to defining and measuring the effectiveness of sanctions. While most research defines the effectiveness of sanctions as their ability to engender partial or total change in the policies of the target countries, some experts argue that the sanctions’ success should be measured in their ability to cause significant economic damage to the target country (Baldwin & Pape, 1998; Jones et al., 2020).

The ability of target countries to contend with the sanctions imposed and contain the economic damage is one of the main reasons that sanctions often fail. Astute confrontation with the sanctions by the target country reduces the pressure to cede to the demands of the countries imposing sanctions. There are various ways of overcoming the burden of sanctions, and how to deal with them depends in part on the types of sanctions imposed, but the state is not the only actor involved. Individual sanctions, imposed on the political or economic elite of the target country, force these elites to take various measures to safeguard their fortunes. Similarly, there are individual actors in the target country who will try to limit the harm caused by sanctions—and perhaps even profit from them—in part by using gray market systems. However, the state still has a central role to play in dealing with economic sanctions. This article focuses on coping with sanctions on a state level and examines the phenomenon of sanctions evasion, which is one of the most important tools available to target countries, and maps the various methods used by target countries to bypass economic sanctions.

The first section of the article considers the use of sanctions (not all of which are economic) by states and international bodies, and examines how target states deal with them, both domestically and internationally. The second part looks at three case studies and surveys the methods used in each to bypass sanctions: North Korea, which has struggled under a sanctions regime for many years, due to its nuclear weapons program; Russia, which seeks in a number of ways to bypass sanctions imposed following its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, having prepared for these sanctions since it invaded the Crimea Peninsula in 2014, and over the next eight years, working to develop mechanisms that would allow it to bypass sanctions; and Iran, a country that has sought to adapt to various sanction regimes for the past four decades and has developed different means to evade them. The article concludes with an analysis of the issue.

The Use of Sanctions

Sanctions are an intermediate option on the spectrum of tools to induce change, between persuasion-based diplomacy and a military operation that uses physical force to establish facts on the ground. The idea of sanctions is the use of coercion for political ends.

Imposition of sanctions serves several goals. The first goal is the desire to influence the policy of the country on which sanctions are imposed—to convey that its behavior is not acceptable and to limit its ability to continue enacting an unwanted policy. The objectives of the actor imposing sanctions can be varied, from pushing the target country to engage in negotiations to seeing it either moderate or completely end a certain policy. The reasons for sanctions imposition also vary. On occasion, sanctions are imposed in response to violent and belligerent activities by the target country, and sometimes for domestic reasons. In the paradigmatic case of South Africa, sanctions were imposed not to change an aggressive foreign policy that attacked the international community, but rather, the racist domestic policy of apartheid. However, there are other goals beyond the goal of influencing the target country. One is to placate one’s own domestic population, which may have called for measures to counter the behavior of the target country. In this case, sanctions can be a relatively easy tool to show the public that the state is taking the measures expected of it. Another goal is to show the international community that the state has responded to the undesirable policy of the target state and aims to deter additional countries from taking unwanted measures. The latter is more relevant to strong countries that are dominant on the international stage. Sanctions can be imposed for one or more of these reasons and, in this sense, are not mutually exclusive. Moreover, in some cases, sanctions are little more than a symbolic or punitive act, when it is understood that the sanctions themselves will not stop the target country and will not alter its behavior, but are nonetheless important to intimate to that country that its actions are unacceptable (Barber, 1979; Daoudi & Dajani, 1983; Galtung, 1967; Jones, 2018; Jones et al., 2020).

Sanctions can be divided into a number of categories that differ from each other based on their scope and identity of the actor(s) imposing the sanctions. Unilateral sanctions are imposed by a single country or by a number of countries individually, while multilateral sanctions are imposed by an international or regional organization. Thus a unilateral sanction imposed solely by the United States only obligates American companies and US citizens, while sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council are multilateral, and by power of Article 25 and 103 of the UN charter, obligate all members of the international community (Happold, 2016).

Unilateral sanctions are imposed by countries based on the rules of countermeasures as defined in international law, which are detailed in the Articles on State Responsibility,[1] whereby any state harmed by the action of another can take countermeasures. When it comes to countries that are not harmed directly, the legal basis for imposing sanctions is less clear (Asada, 2020). Since World War II, no country has imposed more unilateral sanctions than the United States (Barnes, 2016).

Sanctions imposed by the United Nations are the most common example of multilateral sanctions. Sanctions are imposed based on Chapter 7 of the UN Charter, which relates to activity that threatens peace, breaches of peace, and acts of aggression. According to the chapter, sanctions are a political measure taken against violations of world peace; their goal is to strengthen resolutions passed by the Security Council designed to restore peace by changing the behavior of the target country, which has taken measures that threaten peace. Article 41 of the UN Charter allows the imposition of various kinds of sanctions. The Security Council can impose sanctions based on Chapter 14, Article 94, Paragraph 2, whereby the International Court of Justice (ICJ) can authorize the Security Council to take measures that allow it to enforce its decision. The decision making process in the Security Council, where each of the five permanent members has the right to veto any resolution, in essence prevents sanctions being imposed on them and their closest allies (Achilleas, 2020). For its part, the General Assembly has the power to recommend that sanctions be imposed. In addition to multilateral sanctions imposed by the UN, since the late 1990s the European Union has greatly expanded its use of sanctions and has imposed them dozens of times on various countries (Giumelli et al., 2021).

The extent of the sanctions is determined by the various categories: primary sanctions limit economic interactions between citizens and companies from the state imposing sanctions and the target state; secondary sanctions are imposed on citizens and companies in a third country engaged in economic activity with the target country (Sossai, 2020); smart or targeted sanctions, unlike comprehensive sanctions, are imposed on specific individuals—primarily decision makers and the political or economic elite in the target country, sanctioned by freezing assets or restricting travel—and on certain products, such as an arms embargo. The devastating ramifications on civilian society as a result of sanctions imposed in the 1990s, especially the humanitarian crisis created in Iraq, have led to a change in the nature of sanctions imposed, with a clear preference today for targeted sanctions (Happold, 2016).

Notwithstanding their widespread use, sanctions are not necessarily an effective tool for changing the behavior of the target country (Yotov et al., 2021). Sanctions are only successful in around a third of cases, while more pessimistic estimates state that sanctions succeed in altering the policies of the target country in only a small percent of all cases (Pape, 1997; Hufbauer et al., 2009; Morgan et al., 2014). Yet despite this poor success rate, studies show that in the vast majority of cases, countries subjected to sanctions suffer economic contraction and a decline in the quality of life. In other words, economic hardship is almost a constant outcome of sanctions, even if the desired political results are not achieved.

Many studies have highlighted the factors that influence the effectiveness of sanctions. These include: the type and duration of the sanctions; the relationship between the target country and the actor imposing sanctions; the importance of the issue that is the object of the sanctions; the type of regime in the target country; the political and economic stability of the target country; and the desire of third-party countries to help the target country. The chances of sanctions being effective rise when they are imposed against a country that has good relations with the country imposing them and when they have highly developed economic and political ties; when the controversial subject is not particularly important to the target country; and when that country is a democracy, or has a non-democratic but stable regime (Allen, 2005, 2008a, 2008b; Ang & Peksen, 2007; Bapat et al., 2013; Bonetti, 1998; Dashti-Gibson et al., 1997; Drezner, 1999; Drury, 1998; Lam, 1990; Lektzian & Souva, 2007; Van Bergeijk, 1989). At the same time, the response of the target country and how it copes with the burden of sanctions also influence the effectiveness of the sanctions. The ability of the target country to limit the impact of the sanctions, or at least to ease the hardships that sanctions cause its economy, has a direct influence on its desire and willingness to cede to the demands of the authority imposing sanctions (Connolly, 2018).

Coping with Sanctions

Measures that states employ to deal with sanctions can be divided into four main categories: a) steps to adapt the economy to the impact of sanctions b) political steps designed to safeguard the existing regime despite the imposition of sanctions c) measures to oppose the sanctions in the international arena, and d) measures to bypass the sanctions. The latter are a focus of this article.

Adapting the Economy to the Impact of Sanctions

As part of the effort to adapt the economy to the impact of sanctions, countries encourage the development of alternative imports, while promoting the local production of all industrial and agricultural products to replace those products whose import is either banned or limited because of the sanctions. The guiding principle is to reduce dependency on certain countries for imports and significantly increase domestic production capabilities, in order to create self-reliance. As part of this policy, countries can offer various incentives, such as financial help and research and development support to bolster local industry. Moreover, a government can enact a policy of stockpiling vital products and raw materials, allocating them to industry under state supervision, in order to limit, as far as possible, the future shortage of these products and raw materials. Likewise, a state can implement import controls and a system of caps, alongside bans or limits on the import of nonessential goods (like luxury items) if the sanctions include limits on foreign exchange reserves. While adapting its commercial policy, a target country can take fiscal and monetary measures, such as limiting capital flow and altering the exchange and tax rates (Doxey, 1980).

Safeguarding the Existing Regime despite the Sanctions

The regime in the target country can also take nonpolitical measures to safeguard its rule, including with mechanisms to compensate those hit hardest by sanctions, or groups that enjoy political dominance and whose support is vital for the authorities. Within this framework the regime can reduce the economic burden of the sanctions and transfer it from the elites and the groups that support the government to more underprivileged populations in society, who can have no impact on government policy (Doxey, 1980). Moreover, states use propaganda to create public support for their policies and against the sanctions and those imposing them, in order to ensure that the people rally round the flag—in other words, bolstering support for the government and its policies, which would increase the public’s willingness to suffer economic hardship and allow the state to enact unpopular measures to overcome the sanctions. Certain countries can even repress domestic opposition and anyone who opposed the policies for which sanctions were imposed in the first place (Galtung, 1967).

Opposing the Sanctions in the International Arena

Any state that is subjected to sanctions may respond with countermeasures that can include retaliatory sanctions, or it can nationalize assets of citizens of the country or countries responsible for imposing sanctions. The purpose is to harm the other side and exact a price in response to any attempt to harm the economy of the target country (Peksen & Jeong, 2022). A state can also use propaganda directed against the international community, in order to try to convince it that it is the victim of unjustified action on the part of the countries imposing sanctions and thereby gain public sympathy. Moreover, a country can portray itself as willing to negotiate and compromise with the countries imposing sanctions, but in practice, drag its feet and not let those talks progress (Doxey, 1980).

Bypassing the Sanctions

In addition to adapting their economies to sanctions, target countries can take additional measures to enable them to continue to trade and conduct financial transactions with international markets. Measures to bypass sanctions can be divided into measures designed to counter comprehensive or smart/targeted trade sanctions and measures designed to bypass financial sanctions.

In order to bypass trade sanctions, the target country can take steps to diversify its import and export markets. This can be done by developing economic relations with countries that are not only not party to the sanctions regime but are also willing to increase their trade with the target country. Sometimes this trade is conducted under conditions that are less favorable to the target country, since it is forced to offer better terms to these new partners to increase its own attractiveness as a trading partner, and, to a certain extent, to compensate them for the risks involved in trading with a country subjected to sanctions (Doxey, 1980).

In addition to developing trade relations with countries that are not involved in the sanctions, the target country often manages to import goods from countries that are sanctioning it by transporting these goods through third countries, often those in close geographic proximity. In that case, a third country that has not imposed sanctions imports goods from the country imposing the sanctions and then transports them to the target country. This allows goods that cannot be imported because of the sanctions to reach the target country’s market. Another way of evading sanctions is to allow private actors on the target country’s soil to smuggle certain goods. In some cases, the target country can even contact criminal organizations to ensure the steady supply of these goods (Andreas, 2005). Other practices that are common in international trade to bypass sanctions are linked to maritime transport, and involve concealing the country of origin of the goods, camouflaging the identity of the vessel, forging the inventory and documents of a vessel, interfering with the automatic identification system of the vessel, and using a merchant navy sailing under another country’s flag (Feldman, 2022).

In recent years, these has been an increase in the use of financial sanctions limiting the ability of institutions, businesses, and individuals in the target state to trade in financial products—including preventing target country’s access to the foreign currency, its foreign currency reserves, and financial systems. (Cipriani et al., 2023). Consequently, countries under sanctions have also been forced to learn how to bypass restrictions in these areas. One of the measures that a state can take is to create an alternative to the financial systems that have excluded it due to sanctions. One of the most important systems in the financial world is SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, which lets financial institutions exchange messages and sets standards. Countries whose financial systems are disconnected from SWIFT can create an alternative system that works in exactly the same way. For example, in 2015 China launched its own financial messaging system, the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), which is supervised by the Chinese central bank and uses the same standards as SWIFT. Although this alternative system was not set up as part of the Chinese battle against sanctions and currently operates in a relatively limited manner compared to SWIFT, when needed, the system can help bypass financial sanctions since it lessens dependence of Western institutions (Cipriani et al., 2023).

With the rise in the use of cryptocurrency, target countries have identified this new technology as a potential tool for evading sanctions. Cryptocurrencies are not subject to the kind of strict regulation imposed on traditional currencies and they provide either partial or full anonymity for users and their transactions, which makes it very hard for regulatory bodies to identify problematic transactions and allows any element under sanctions to bypass the limits on the traditional financial system, including the use of the US dollar. One prime example of a target country expressing an interest in cryptocurrency is Venezuela, when President Nicolás Maduro announced the launch of the petro, the state-issued cryptocurrency, which was backed by the country’s energy reserves (Wronka, 2022).

There are various ways that a target country can use cryptocurrency to limit the impact of financial sanctions and bypass the restrictions imposed on it by creating capital outside of the financial system or reducing its use of foreign currencies. One way is to steal cryptocurrency by means of government-backed cyberattacks; another way is to mine cryptocurrency. The third way is to create a national cryptocurrency that is subject to the regulations of that country’s central bank and is backed by gold or other commodities, as in the case of Venezuela. Another possible way is to create one cryptocurrency for a number of countries, backed by the currencies of those countries. This idea has been floated by the BRICS group—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (Magas, 2019). Finally, a target country can encourage its citizens to use cryptocurrency (Konowicz, 2018).

There are several ways that cryptocurrency can be used. The simplest way is the direct transfer of cryptocurrency assets from one electronic wallet to another, which accommodates simple transactions. Another system, suitable for large institutions, is the use of intermediaries: banks in the target country transfer assets to banks in a third country, which convert those assets from the local currency into international currencies like the US dollar or the euro, and then transfer them to intermediaries in a different third country. There, the assets are converted into cryptocurrency and are distributed among many different electronic wallets to conceal their source. Subsequently, these assets can be used by simply converting them into traditional currencies or other cryptocurrencies for use in various business deals (Ahari et al., 2022; Macfarlane, 2021). It is hard to gauge to what extent the use of cryptocurrency can replace the use of traditional currencies, especially when dealing with larger-scale deals that are easier to follow and identify (Ahari et al., 2022). However, this is one of the methods available for states, combined with other measures used by them.

Another method of evading sanctions is to reduce the use of foreign currencies, especially the US dollar. The target country can promote the use of its local currency, especially when dealing with countries with which it has close economic and political ties. It can move part of its trade over to the currency of its trade partner. In certain cases, trade can also be conducted using the barter system (McDowell, 2021).

Case Studies on Sanctions Evasion

In order to demonstrate how sanction evasion works, focus now turns to three case studies. The first is North Korea, which has been under the yoke of sanctions for the past 17 years. The second is Russia, which has tried for over a year to bypass Western sanctions in a number of ways. Finally, there is Iran, which has been subject to a range of changing Western sanctions for over four decades. These three case studies were chosen because of the material differences between them. Russia is the most current case and involves a large global economy (the 11th largest in the world in terms of GDP); it is an important energy exporter and figures prominently in the global economy. North Korea is a small country that has confronted sanctions for a long period; it is highly dependent on energy imports and has never integrated to a large extent in the international financial system. In contrast, Iran is a special case of a country dealing with a sanctions regime that ebbs and flows. Over the course of the past 40 years, Iran has taken advantage of suspensions of the sanctions to develop an economy capable of dealing with fresh sanctions, and it is evident how its methods have changed over time and in accordance with conditions and the lessons learned. Like North Korea, sanctions have been imposed on Iran in recent years because of its nuclear program. Like Russia, Iran is an energy exporter, but over the years it has tried to lessen its reliance on these exports, and just as the Iranian economy has become more diverse, so too have its methods of evading sanctions. Similarly, all three of these countries face more sanctions than any other target country. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Moscow has been at the top of the list of countries with imposed sanctions, followed by Iran; North Korea is in fourth place (Zandt, 2023).

The North Korean case

Since 2006, when North Korea conducted its first nuclear test, the country has been under a sanctions regime imposed by various international bodies and countries. These sanctions include trade embargoes and restrictions, especially in arms and military equipment; financial restrictions and limits on investment; assets freeze; and travel bans (“Fact Sheet,” 2022). Despite these sanctions, North Korea has continued to export coal, one of most important parts of its economy, most of it to the Chinese market. Similarly, it also exports oil and trades various goods, including weapons and other military equipment (Kim, 2021). Although North Korea is perceived as isolated and disconnected from the global economy, in practice it has managed to run its economic and financial systems, notwithstanding the limits imposed by sanctions, thanks to several methods it has developed over the years.

Methods of Bypassing Sanctions

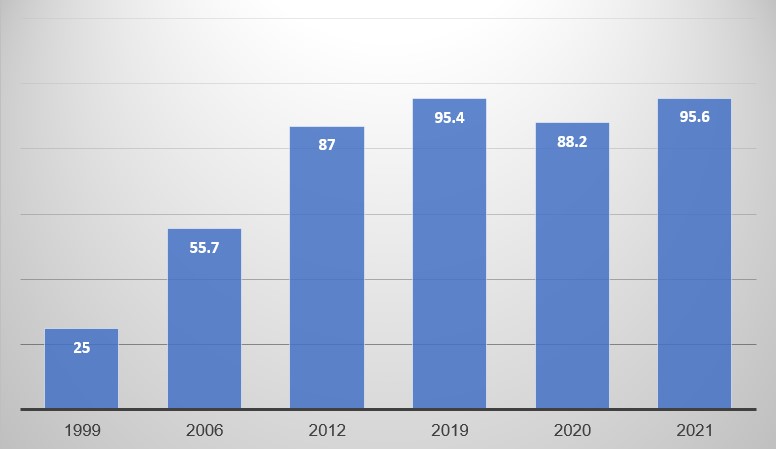

The first method is the use of third-party countries as export markets, import markets, and transit states. North Korea’s primary trading partner is China (Figure 2). Data show an asymmetrical dependency between the two countries, since two-thirds of North Korea’s exports are sent to China and more than 90 percent of its imports come from China (“Korea, North,” 2023). China helps North Korea bypass sanctions in a number of ways, in part because of the countries’ geographic proximity. A shared border also allows China to act as a third-party country, through which, using straw companies and mediators, North Korea can import from countries that have joined the boycott against it. These companies ostensibly import goods from China for personal or local use, but in practice, they transport them to North Korea. The shared border allows for smuggling of goods and gray trade, which has the blessing of officials on both sides of the border. North Korea also sells China fishing rights in its territorial waters (Watts, 2020).

Figure 2: Trade between North Korea and China, out of total North Korean international trade (in percent) | Source: Jobst, 2023

Moreover, North Korea smuggles various types of weapons and military equipment to more than 30 nations, territories, and armed groups, in violation of various sanctions. Among the countries that receive North Korean weapons are Iran, Syria, Egypt, Yemen, Myanmar, and Libya. African nations are among the most import of North Korea’s export markets, some of which are themselves subject to sanctions and have neither the desire not the ability to enforce sanctions imposed by the UN (Young, 2021). North Korea also has extensive and long-term ties with some of these countries in the development of ballistic missiles. This trade allows North Korea to obtain foreign currency and thereby mitigate the impact of the sanctions—one of whose stated goals is to prevent it from obtaining foreign currency (Griffiths & Schroeder, 2020).

Another measure by North Korea in recent years is cyberattacks against financial institutions. There is evidence that North Korea has tried of late to attack banks and cryptocurrency exchanges, in an effort to steal foreign currency and virtual assets in other countries. According to the Wall Street Journal, in the past three years alone, North Korean hackers have stolen around $3 billion of cryptocurrency (McMillan & Volz, 2023). At the same time, using this fortune requires the assistance of intermediaries from other countries, so the total that North Korea actually earns from such activity could be far less (Rosenberg & Bhatiya, 2020).

A third method is to obscure the source of the money, transfer it physically, and use barter. To facilitate payment and money transfers, North Korea employs a number of methods. First, some of its trade is conducted in barter. Second, in some cases, money is transferred using couriers (who could also be diplomats representing the country). To transfer money via international financial systems, North Korea transfers money to the bank accounts of its embassies and diplomats, and sometimes their families; transfers money to front companies or to small banks that do not have the resources to fully investigate the source of the money; or transfers the money several times between banks in different countries to make it harder to track the source (Mallory, 2021).

In addition, North Korea takes advantage of the mobility and immunity of its diplomatic representatives to facilitate smuggling. Arms and other goods are smuggled with the significant help of North Korean diplomats wherever they might be stationed, and they act as intermediaries and sometimes even as smugglers. They play a key role in North Korea’s smuggling operations, from the first approach to a potential client up to the relay of the goods, using their diplomatic immunity, which allows them far greater freedom of movement. To transport banned goods to Syria, for example—a country that it itself is under a sanctions regime and therefore is subject to far tighter supervision—documents needed to claim goods that were sent to the Syrian port of Latakia were sent to the North Korea embassy in Damascus, which sent its diplomats to the port to collect the goods. These same diplomats can also help smuggle the material for manufacturing weapons and the money from arms deals on civilian flights (Griffiths & Schroeder, 2020).

A fifth method used by North Korea to bypass sanctions is maritime smuggling, using various tactics to obscure information about the cargo and identity of the parties involved. These tactics include transferring cargo from one vessel to another in open seas (mainly with Russia and China) to conceal the origin of the goods. This is the primary method used to smuggle oil into North Korea, alongside the use of flags of convenience, including the flags of Cambodia, Sierra Leone, and Belize (Ministry of Defense, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, & Gavin Williamson, 2019). Another tactic is to deactivate or interfere with the vessel’s automatic identification system (AIS) which transmits the identity, location, destination, and other information about the ship. Deactivating the AIS is a violation of the rules of the International Maritime Organization (IMO). While this tactic has been prevalent for arms smuggling for years, its use has expanded recently to other goods, including coal and oil to North Korea, and from there to other countries. Moreover, the North Korea Maritime Administration helps anyone under sanctions forge documents and maritime mobile service identities (MMSIs) (Trainer, 2019).

When North Korea uses its fleet of ships to smuggle weapons and other banned goods, it conceals these goods under large quantities of other goods. This technique helps hide contraband during inspections that take place outside the port, since it is impossible to examine the entire cargo. Similarly, North Korea does all it can to limit such inspections, by not allowing them on vessels carrying its flag. Without this permission, inspections cannot take place in international waters (Griffiths & Schroeder, 2020).

A sixth method is to establish shell companies or fronts and cooperative projects. In order to have access to the international financial system and allow maritime and aerial trade and commerce while using international cargo and logistics companies, especially when trading in arms and military equipment, North Korea uses fronts and shell companies in other countries (Mallory, 2021). Fronts are genuine companies and in some cases portions of their activity are totally legal, but they are also used as fronts for illegal activity and money laundering since they are not subject to sanctions and are not suspected of illegal activity. Straw companies are not engaged in any genuine business and exist only on paper (Kharon, 2022). North Korea has made widespread use of both these methods, sometimes camouflaging the activity using a number of such companies simultaneously. Similarly, North Korean companies establish joint ventures with foreign banks and companies based in China, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Panama, Russia, Singapore, and many other countries, and they are usually established with the help of private foreign actors. This is how the country manages to conceal its involvement in the supply chain and pay for goods. The assistance of foreign nationals is especially important in countries where the law stipulates that a local citizen must be a majority shareholder in a company (Hastings, 2022).

Finally, North Korea uses forged documents, concealment, and misinformation. It uses fake export licenses, consignment notes with inaccurate, vague, or partial descriptions of the goods—a particularly effective method when combined with maritime shipping of sealed containers (Griffiths & Schroeder, 2020)—as well as fake identities of businesspeople involved in the fronts and straw companies. Moreover, North Korea launders vessels that are under sanctions by changing the name, the IMO-registered number, and owner, thereby allowing the vessel to continue operating despite sanctions (O’Carroll et al., 2021). It also tries to conceal the trademarks and other identifying features of weapons that it smuggles, rebranding them with fake tags and painted parts, to make them harder to identify (Griffiths & Schroeder, 2020).

The Russian Case

Russia has been under sanctions since its 2014 invasion and annexation of the Crimean Peninsula. The invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 prompted another, unprecedented wave of sanctions against Moscow (Congressional Research Service, 2022), imposed by Western nations, under the leadership of the United States and European Union. These sanctions can be divided into several categories: trade and investment limitations, financial restrictions, personal sanctions, sanctions against Russian institutions, and travel restrictions (Nikoladze & Donovan, 2023).

Since sanctions were imposed in 2014, and even more so since February 2022, Russia has adopted a variety of measures to lessen their impact, including advancing preparations for the possibility that sanctions would be imposed, studying the lessons from other target countries, like Iran, Venezuela, and North Korea, which have been under sanctions regimes for many years, and even imposing counter-sanctions (“Factbox,” 2022; Ridgwell, 2023). Some of the methods Russia uses to bypass sanctions are trade related and some are financial.

Methods of Bypassing Sanctions

In the area of commerce, three main methods are used to bypass sanctions: parallel imports; concealed origins of goods; and mitigated import and export regulations for alternative markets. The first two came as an immediate response to the unprecedented sanctions that were leveled on Russia after it invaded Ukraine in February 2022, while the final method developed gradually following the sanctions imposed after the 2014 invasion of Crimea and ripened during the current round of sanctions. From the start of the campaign in Ukraine, Russia has allowed what it calls “parallel imports,” namely, the import of goods without the manufacturer’s permission (“Russia and Sanctions Evasion,” 2022). These imports usually arrive from a country that shares a border with the target country or via countries that serve as large commercial hubs (Lukaszuk, 2021). One of the primary methods of importing goods to Russia is via members of the Eurasian Economic Union—a regional economic organization of several post-Soviet states, including Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan. They act as third-party countries via which goods that are under sanctions can still be imported to Russia. For its exports, Russia uses, inter alia, the International North-South Transport Corridor, a multi-mode transport network that runs via Iran and Azerbaijan to India (Okumura, 2023). Any product that cannot be imported in one piece is imported as component parts, which are then assembled inside Russia (IntegrityRisk, 2022).

Similarly, concealing the origin of the goods and easing import laws are vital for maintaining Russia’s economic power, given its massive reliance on energy exports. Oil is a critical component in the Russian economy, and before the war in Ukraine, more than one third of Russia’s total exports were oil and oil-related products (Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2022). Given the huge importance of these exports for the Russian economy, Moscow examined several methods to circumvent the restrictions. When it comes to exports, there are more specific ways of evading sanctions on certain goods—and oil is among those products whose origins can be concealed. One way Russia uses is to mix its oil with oil produced elsewhere, creating a hybrid commonly referred to as “Lithuanian” or “Turkmen” blends, as long as the proportion of Russian oil in the blend is less than 50 percent. This ensures that the product is not technically Russian oil (IntegrityRisk, 2022). In order to facilitate parallel imports from a third-party country, Russia has relaxed the law banning the import of certain goods without the permission of the trademark holder (IntegrityRisk, 2022). In other cases, Russia has used fake certificates of origin to import goods that are under sanctions (Lukaszuk, 2021).

Russia also developed tactics of sanctions circumvention in a field of marine transportation. A key element in evading sanctions is learning from the experience of countries subject to sanctions. North Korea, Iran, and Venezuela have struggled for many years with sanctions that harm their international trade, which is usually transported by sea. Therefore, over the years, they developed tactics for camouflaging information about their vessels and their destination—tactics that have been adopted by Russia (“Russia and Sanctions Evasion,” 2022). After the outbreak of the Ukraine war, there was an increase in the number of Russian ships that sailed without reporting their destination and disappeared from the maritime tracking system. For example, the Russian state-owned shipping company Sovcomflot, which is the subject of international sanctions, failed to provide destination information regarding around one third of the tankers in its fleet. In addition, there is also a practice whereby oil is transferred from one vessel to another in the open sea, to conceal the origin of the product (IntegrityRisk, 2022). Another method of covering traces is to fly a flag of convenience—the flags of countries like Panama, the Marshall Islands, and Liberia—which charge a small fee to register a vessel in their country and, more important, have far laxer standards than many other countries when it comes to inspections. In some cases, vessels have been known to fly the flag of such countries without any registration at all (MI News Network, 2023).

Another problem that Russia faces is its inability to insure the vessels transporting Russian oil that does not adhere to the price range dictated by the sanctions, which was designed to prevent their evasion. To deal with this problem, Russia set up a government-backed company of its own, and the country’s central bank was forced to contribute around $4 billion toward the company (Braw, 2023; “Russia and Sanctions Evasion,” 2022).

The three main Russian methods of evading sanctions were developed following the imposition of sanctions in response to the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and were designed to prepare Russia for the day when it would have to deal with a wide-ranging wave of sanctions. The understanding that the 2014 sanctions were primarily imposed by Western states led Russia to the conclusion that its main preparations must focus on dealing with Western sanctions. Therefore, for the next eight years, Russia tried to build its “siege economy,” which would be impervious to Western sanctions. First, Russia realized that in terms of international trade, it would have to find alternative markets to the Western nations that were liable to impose sanctions. Russia succeeded in finding export markets for what it considered strategic products, especially energy, and increase the scope of its exports to actors that it believed would not impose sanctions in case of armed conflict—countries like China and India. Russian exports to China, India, and Turkey grew significantly from the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and mitigated the impact of Western sanctions. The Turkish example is the most extreme since, within a single year, Turkish imports of Russian goods doubled—from $29 billion in 2021 to around $60 billion during the first year of the war (Kenez, 2023). The bulk of Russia’s exports to Turkey is fuels, but it is joined by steel, iron, and grain.

The main goals of both the other tools that were developed after sanctions were imposed in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea are to ease the Russia’s financial situation: reducing its use of the US dollar, since it is the currency that can be controlled by the United States; and developing alternatives to the SWIFT clearing system, which is under the control of Western states.

Reducing the use of the US dollar: Following the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, and even more so after the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia tried to scale back the use of the US dollar in its international transactions and to increase the use of the ruble and the national currencies of the nations with which it trades: India, China, and Iran. For example, the transaction for the sale of coal to an Indian company was made in Chinese yuan (“Russia and Sanctions Evasion,” 2022). Indeed, in the year since the outbreak of the war, the Chinese yuan has become the most-used foreign currency in Russia (Bloomberg, 2023). However, the use of the ruble in transactions with other countries does not apply only to those countries that are not part of the sanctions regime. Even Western companies based in places like Germany and Italy, which purchase Russian gas, are forced to use the ruble to complete the transaction (Okumura, 2023). In some cases, the transaction is completed using the barter system. For example, in its trade with Syria, Russia was happy to barter grain for olive oil and vegetables (“Russia and Sanctions Evasion,” 2022).

Similarly, since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, there has been a dramatic change in the attitude of Russian political and financial institutions to the use of cryptocurrency: efforts to limit its use yielded to regulations to govern the issue, due to the understanding that these currencies could be the answer to a variety of problems causes by financial sanctions, especially when it comes to individual sanctions (Ahari et al., 2022).

Alternatives to the SWIFT payment system: SWIFT plays a key role in the international financial system. It is the system used to relay information between various bodies, which facilitates financial transactions and is responsible for most of the international financial communication in the world. It is used by more than 11,000 banks and other financial institutions (Jones, 2022). After the imposition of sanctions in 2014, Russia created the System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS), its own SWIFT alternative. Even though it has not garnered much popularity in other countries, Russia has tried to encourage its use, and especially since February 2022. Moreover, Russia also developed the National Payment Card System (NSPK), which provides payment services to anyone with an MIR card inside Russia. Therefore, this system provides a partial alternative to credit cards like Visa and Mastercard, whose use in Russia has been limited by the companies. Like with SPFS, Russia is trying to expand use of this system to other countries, especially countries that are popular destinations for Russian tourists (Mahmoudian, 2023). This element in sanctions evasion is highly important to Russia, both operationally and conceptually, since the West believes that denying a country access to SWIFT is a doomsday weapons that should not be used lightly. Indeed, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire described SWIFT as “the financial nuclear weapon” (Leali, 2022). Therefore, the establishment of mechanisms that allow a country to survive without access to SWIFT would go a long way to determining whether Russia would withstand the pressure of sanctions.

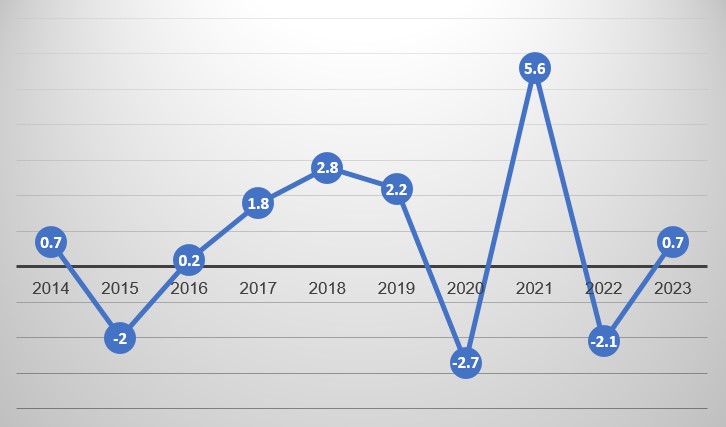

These sanction-evading tools have done much to mitigate the impact of economic sanctions against Russia. In the first few months of the sanctions, important international financial organizations, including the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the OECD, all believed that Russia’s economy would shrink by up to 10 percent in 2022 and that 2023 would see GDP drop by another 3 percent. As shown in Figure 3, which is based on data from the International Monetary Fund in the second quarter of 2023, the economic shrinkage was far more moderate than predicted, and it now seems likely that 2023 will see GDP grow slightly, rather than shrink further. It appears that evading sanctions is a significant tool in Russia’s toolbox for dealing with the unprecedented wave of sanctions imposed after its invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 3. Fluctuation of Russian GDP (in percent) | Source: International Monetary Fund, 2023; GDP growth for 2023 is based on IMF forecast

The Iranian Case

Iran has been subject to a variety of sanctions since the late 1970s, and until sanctions were imposed on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine, Iran was the target state with the largest number of sanctions imposed on it (Zandt, 2023). Over the course of the past few decades, and especially since the mid-1990s, different types of sanctions have been leveled on Iran by various states including the United States, Canada, and Australia, as well as multilateral sanctions by international organizations like the United Nations and the European Union. These sanctions include restrictions on foreign trade, especially in the fields of energy and technology, financial services, a ban on insurance services, and travel restrictions (Laub, 2015; “Sanctions against Iran,” n.d.). Iran represents an interesting case of an actor for whom sanctions are a repeated game. It takes advantage of the intervals between the waves of sanctions to prepare for the next sanction wave. This refers not only to how Iran has used these pauses to attract foreign investment and increase its foreign trade but also to the way it learns from one sanction campaign to the next how to reduce the ability of future sanctions to harm its economy. Moreover, it uses the breaks between sanctions to improve its various methods of evading sanctions.

Methods of Bypassing Sanctions

Over the years, Iran has developed a variety of methods to evade sanctions, and it continues to improve them in order to overcome the challenges sanctions pose to its economy. The current sanctions campaign, imposed when the United States withdrew from the Iranian nuclear agreement in May 2018, is especially challenging, given that it also includes secondary sanctions. The US withdrew from the JCPOA unilaterally but imposed sanctions that barred American companies and citizens from engaging in commercial ties with Iran. However, these sanctions also apply indirectly to non-American companies, which are then forced to choose between trading with Iran and trading with the United States; those choosing the former will find it hard to conduct trade relations with the US. Therefore, the first measure that Iran undertook to evade sanctions of this kind is allowing businesspeople to obtain a second citizenship. Officially, Iran does not recognize dual citizenships, but in order to make it easier for businesspeople trying to evade sanctions by registering their companies in other countries, it unofficially allows them to obtain citizenship from tiny countries like St. Kitts and Nevis. Thereafter, they are entitled to open bank accounts and register companies in these countries—that will subsequently serve as fronts for Iranian companies (Ajiri, 2018; Sharafedin & Lewis, 2018). This activity also enables Iranian businesspeople to work with companies that do business with the United States and who are concerned about American sanctions.

The second method is the sale of oil. The sanctions on Iran’s energy sector harmed its ability to produce and sell oil. First, the lack of advanced technology and investment in infrastructure damaged its production capabilities. Second, the concern over American sanctions prevents Iran from exporting large quantities of oil when sanctions are in effect, something it has been able to do between waves of sanctions. Therefore, over the years Iran has lessened its dependence on oil and started to develop other areas to contribute to its economy and diversify its sources of income during periods of no sanctions, and particularly when sanctions are in effect. However, Iran has not given up on oil revenues, which still account for a significant share of its income. Thus in order to promote oil sales, affected by the sanctions, Iran offers improved terms for potential customers, including discounts on the oil itself and on maritime transportation. In addition, since international insurance companies refuse to insure Iranian oil cargo due to the sanctions, the Islamic Republic insures its own cargo (Dawi, 2023; “Iran Offers,” 2018; Verma, 2013, 2018). China is the chief beneficiary of the generous terms that Iran offers and helps it to evade sanctions. In the first months of 2023, Iran exported around 1,000,000 barrels of oil to China every day (Bloomberg News, 2023). According to various estimates, China enjoys a 25-percent discount on the oil it imports from Iran.

Another method used by Iran, connected to oil but relevant to other goods as well, involves maritime transportation. Iran uses a number of methods in order to enable oil trade and its sea transportation. It uses its own vessels to transport purchased oil to the buyer since foreign maritime companies are reluctant to trade with Iran over fear of sanctions (Dagres & Slavin, 2018). These vessels use various means to disguise their identities, including deactivating location systems, changing the color of the vessel, and even altering its name. Iran also uses the technique of oil transfer from one vessel to another in the open sea (Karagyozova, 2021). This technique enabled Iran to make use of another way of smuggling oil: mixing Iranian oil with oil from Iraq. This way, Iran can conceal the origin of the oil and make it hard for governmental bodies to correctly identify Iranian oil (Lipin, 2022).

In one incident that came to light in March 2020, the Iranian-owned Polaris 1 tanker transported Iranian refined oil to another tanker that was carrying Iraqi oil. The second tanker, the Babel, was operated at the time by Rhine Shipping DMCC, which is owned by a businessman from the United Arab Emirates—an Iraqi-born British citizen. However, the prevalent assumption is that Iran no longer uses this method in any significant manner since it is not profitable enough and has attracted too much attention (Lipin, 2022).

Another method that may be gaining greater use of late is forging AIS data. Iran has equipped its tankers with devices that falsify AIS signals, sending out inaccurate data regarding the location of the vessel, to make it harder to track. Some argue that currently, this method used to export most of Iran’s oil (Lipin, 2022). Forged AIS signals, accompanied by false cargo documents, allows Iran to claim that the oil is actually from Iraq, freeing it of the need to actually transfer the oil from one vessel to another in the open sea (Lipin, 2022). In this context, Iran makes widespread use of forged documents to conceal the origin of the product in question (Office of Foreign Assets Control, 2020).

A fourth method used to evade sanctions is front companies, banks, and investments. Iran makes widespread use of a network of front companies—located, inter alia, in China, Iraq, Lichtenstein, and the United Arab Emirates—to facilitate the import and export of various goods and to transfer money. In some cases, this also involves the assistance of nations from these countries, who act as business partners and allow to open companies in their names. This network is used to open bank accounts for Iranian companies, which enables them to sell their products to foreign companies. In addition, Iranian importers use these funds to pay for goods. For example, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) opened many companies in Georgia under the name of local Georgian business partners (“NEWS,” 2023; Dagres & Slavin, 2018; Hamad, 2022).

Another method is investing in foreign companies in order to influence their activity. For instance, Iran’s Foreign Investment Company invests in companies in various countries to ensure access to vital products like medical equipment and medicine, technology, and services. For example, the company invested $3 million in the purchase of a bankrupt pharmaceutical factory in France, to secure the access to medicine against infectious diseases (Dagres & Slavin, 2018). In other cases, to import goods, Iran relies on the assistance of intermediaries with citizenship in the United Arab Emirates and Iraq. The intermediaries buy products in those countries and then smuggle them into Iran (Dagres & Slavin, 2018).

The final method, which has become very relevant of late, is the increasing use of cryptocurrency. The current sanctions regime has impinged severely on Iran’s ability to use the US dollar, which is the primary currency in the international economic system. The financial sanctions imposed on Iran also severely impact the value of the rial, and the current wave of sanctions sent the Iranian currency tumbling to a historic low versus the US dollar (“Iran’s Currency,” 2023). As a result, , several months after the imposition of the current round of sanctions in 2018, the Iranian regime officially recognized the mining of cryptocurrency in 2019. All Iranians involved in this activity were required to identify and register themselves, pay for electricity used for mining, which uses a lot of energy, and sell their reserves of Bitcoin to the Iranian central bank. In addition, in August 2022, the Iranian government approved the use of cryptocurrency to pay for imports (Iddon, 2022). The global rise in the use of these currencies has been highly beneficial for Iran and came at the perfect time to help it evade secondary sanctions, since the difficulty in identifying the parties to this exchange helps private individuals engage in trade with Iran without fear.

Conclusions

Since nations started to use the sanctions weapon with greater frequency in the 20th century, there has been more recourse to various ways and means to evade them. Moreover, in an age when information flows freely and easily from one place to another, states have increasingly capable of dealing with sanctions. The ability of various actors to learn from experience, and even to consult in real time with other states, has enhanced these sanction-evading methods even more. There are, therefore, three main insights that can be drawn for any actors interested in using economic sanctions as a foreign policy tool to achieve political goals:

Insight 1: Attempt to harm the key trade partners of countries trying to evade sanctions. One pattern of behavior that repeats itself, as can be seen from the case studies, is the use of trade alternatives to evade sanctions. Whether these alternatives are in the form of countries that had extensive commercial ties with the target country before sanctions were imposed but did not join the campaign, or whether they were countries that became an alternative only because of the sanctions, efforts to neutralize these alternatives should be one of the focuses of the campaign. Diplomatic outreach to the relevant actors is vital in order to ensure that the target country suffers significant economic contraction, which could limit its ability to survive the sanctions. These efforts could be the classic carrot-and-stick approach: on the one hand, promising economic incentives to those countries that trade with the target country and, at the same time, imposing economic sanctions on any company from a country that is being used as a trade alternative. The stick, in this case, is known in professional jargon as secondary sanctions. In the case of Russia, for example, this could mean that any Turkish or Indian company doing business with Russia would be susceptible to European or American sanctions and would not, therefore, be able to do business with the West. Note that in all three of the case studies discussed above, it is clear that the economic ties that were forged with China represented a lifeline for those target countries. China is not just another country helping evade sanctions; it is the second largest economy in the world and its contribution to sanctions evasion cannot be understated. Therefore, having China join sanctions campaigns is vital if they are to succeed.

Insight 2: Develop mechanisms to help thwart sanctions evasion. Evading sanctions by trading with other countries is an important weapon, however, the arsenal target states possess is very varied. Therefore, countries imposing sanctions should coordinate closely to identify the possible loopholes in their sanctions. These mechanisms must focus on the cybersphere, which would facilitate the enforcement of sanctions by identifying forgeries, such as false certificates of origin, tracking transportation of goods, use of cryptocurrency, and creation of mechanisms that can severely restrict the target country’s ability to engage in the financial markets.

Insight 3: Countries imposing sanctions must recognize the many limitations of this tool. Even if they manage to recruit the main trading partners of the target country and even if they develop methods of thwarting efforts to evade sanctions, the target country will always prefer to find new ways of evading sanctions than to give in to them. Recognizing the limitations of sanctions as a tool is vital both for decision makers, who must see things as they are, and for the public in those countries imposing sanctions, which could erroneously expect immediate results.

There is nothing unique about the way that North Korea, Iran, and Russia evade sanctions. The methods that they use have become the modus operandi for any country that has been subjected to sanctions, but this does not mean that sanctions evasion is a huge success that prevents any damage to the target country’s economy. In the cases of Russia and Iran, and even more so in the case of North Korea, sanctions have had a dire economic effect. At the same time, recourse to methods of evasion helps to mitigate the economic impact. It seems that the more sophisticated the methods of evading sanctions become, the more they provide a corresponding explanation of the relatively low success rate of sanctions in achieving their goals.

References

Achilleas, P. (2020). United Nations and sanctions. In M. Asada (Ed.), Economic sanctions in international law and practice (pp. 24-33). Routledge.

Ahari, A., Duong, J., Hanzl, J., Lichtenegger, E. M., Lobnik, L., & Timel, A. (2022). Is it easy to hide money in the crypto economy? The case of Russia. Focus on European Economic Integration, Q4/2271, 71-89. https://tinyurl.com/37rhsp9x

Ajiri, D. H. (2018, August 30). Iranian in name only: Dual nationals hide Iran ties to avoid US sanctions. France24. https://tinyurl.com/4m5v7rn7

Allen, S. H. (2005). The determinants of economic sanctions success and failure. International Interactions, 31(2), 117-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050620590950097

Allen, S. H. (2008a). The domestic political costs of economic sanctions. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(6), 916-944. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002708325044

Allen, S. H. (2008b). Political institutions and constrained response to economic sanctions. Foreign Policy Analysis, 4(3), 255-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-8594.2008.00069.x

Andreas, P. (2005). Criminalizing consequences of sanctions: Embargo busting and its legacy. International Studies Quarterly, 49(2), 335-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-8833.2005.00347.x

Ang, A.U. J., & Peksen, D. (2007). When do economic sanctions work? Asymmetric perceptions, issue salience, and outcome. Political Research Quarterly, 60(1), 135-145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912906298632

Asada, M. (2020). Definition and legal justification of sanctions. In M. Asada (Ed.), Economic sanctions in international law and practice (pp. 1-18). Routledge.

Baldwin, D. A., & Pape, R. A. (1998). Evaluating economic sanctions. International Security, 23(2), 189-198. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/446933

Bapat, N. A., Heinrich, T., Kobayashi, Y., & Morgan, T. C. (2013). Determinants of sanctions effectiveness: Sensitivity analysis using new data. International Interactions, 39(1), 79-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2013.751298

Barber, J. (1979). Economic sanctions as a policy instrument. International Affairs, 55(3), 367-384. https://doi.org/10.2307/2615145

Barnes, R. (2016). United States sanctions: Delisting applications, judicial review and secret evidence. In M. Happold & P. Eden (Eds.), Economic sanctions and international law (pp. 197-225). Hard Publishing.

Bloomberg. (2023, April 3). China’s yuan is now the most traded currency in Russia as sanctions knock the US dollar out of the top spot. Fortune. https://tinyurl.com/4k2jftcs

Bloomberg News. (2023, April 6). Iran oil snapped up by Chinese private refiners as market shifts. Bloomberg. https://tinyurl.com/95rcw7xt

Bonetti, S. (1998). Distinguishing characteristics of degrees of success and failure in economic sanctions episodes. Applied Economics, 30(6), 805-813. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368498325507

Braw, E. (2023, January 30). Ships are flying false flags to dodge sanctions. Foreign Policy. https://tinyurl.com/2uewwjez

Cipriani, M., Goldberg, L. S., & La Spada, G. (2023). Financial sanctions, SWIFT, and the architecture of the international payment system. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 37(1), 31-52. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.37.1.31

Congressional Research Service. (2022, December 22). Russia’s war against Ukraine: Overview of U.S. sanctions and other responses. https://tinyurl.com/yecn4nh2

Connolly, R. (2018). Russia’s response to sanction: How Western economic statecraft is reshaping political economy in Russia. Cambridge University Press.

Dagres, H., & Slavin, B. (2018). How Iran will cope with US sanctions. Atlantic Council. https://tinyurl.com/5cxnx9fm

Daoudi, M., & Dajani, M. S. (1983). Economic sanctions: Ideals and experience. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Dashti-Gibson, J., Davis, P., & Radcliff, B. (1997). On the determinants of the success of economic sanctions: An empirical analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 41(2), 608-618. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111779

Dawi, A. (2023, January 26). Iran boosts cheap oil sale to China despite sanctions. Voice of America. https://tinyurl.com/52kyyjar

Doxey, M. (1980). Economic sanctions and international enforcement. Macmillan Press.

Drezner, D. W. (1999). The sanctions paradox: Economic statecraft and international relations. Cambridge University Press.

Drury, A. C. (1998). Revisiting economic sanctions reconsidered. Journal of Peace Research, 35(4), 497-509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343398035004006

Elliott, K. A. (1997, October 34). Evidence on the costs and benefits of economic sanctions. Peterson Institute for International Economics. https://tinyurl.com/yc8bwehs

Fact sheet: North Korea sanctions. (2022, May 11). Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. https://tinyurl.com/d9ch6j38

Factbox: Russia's response to Western sanctions. (2022, May 13). Reuters. https://tinyurl.com/4wa8vph4

Feldman, N. (2022). Rallying around the “flag of convenience”: Merchant fleet flags and sanctions effectiveness. Marine Policy, 143, 05129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105129

Galtung, J. (1967). On the effects of international economic sanctions, with examples from the case of Rhodesia. World Politics, 19(3), 378-416. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009785

Giumelli, F., Hoffmann, F., & Książczaková, A. (2021). The when, what, where and why of European Union sanctions European Security, 30(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2020.1797685

Griffiths, H., & Schroeder, M. (2020). Covert carriers: Evolving methods and techniques of North Korean sanctions evasion. Briefing Paper. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands. https://tinyurl.com/5n9a8zb5

Halliday, D. J. (1999). The impact of the UN sanctions on the people of Iraq. Journal of Palestine Studies, 28(2), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.2307/2537932

Hamad, A. (2022, June 22). How Iran set a sanctions evasion network to keep its economy afloat: Report. Alarabiya News. https://tinyurl.com/5xbu5acr

Happold, M. (2016). Economic sanctions and international law: An introduction. In M. Happold & P. Eden (Eds.), Economic sanctions and international law (pp. 1-12). Hard Publishing.

Hastings, J. V. (2022). North Korean trade network adaptation strategies under sanctions: Implications for denuclearization. Asia and the Global Economy, 2(1) 100031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aglobe.2022.100031

Hufbauer, G. C., Schott, J. J., & Elliott, K. A. (1990). Economic sanctions reconsidered. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Hufbauer, G. C., Schott, J. J., Elliott, K. A., & Oegg, B. (2009). Economic sanctions reconsidered. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Iddon, P. (2022, November 14). How Iran is cashing in on cryptocurrencies to evade US sanctions. Arab News. https://tinyurl.com/yt4nebj2

IntegrityRisk. (2022, August 10). Top ten most common Russian sanction evasion schemes. Integrity Risk International. https://tinyurl.com/ybabmbhx

International Monetary Fund. (2023, April). Real GDP growth. World Economic Outlook. https://tinyurl.com/y9drpa6r

Iran offers oil discounts to keep its Asian customers. (2018, August 14). Radio Farda. https://tinyurl.com/4f7yr2kb

Iran's currency falls to record low as sanctions to continue. (2023, February 20). Reuters. https://tinyurl.com/4fh6phcw

Jobst, N. (2023, June 15). North Korea’s trade with China as share of total foreign trade 1999-2021. Statista. https://tinyurl.com/mpmu8fun

Jones, C. (2018). Sanctions as tools to signal, constrain, and coerce. Asia Policy, 25(3), 20-27. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2018.0037

Jones, C. (2022, February 25). The impact of throwing Russia out of Swift. Financial Times. https://tinyurl.com/2mb5mjss

Jones, L. (2015). Societies under siege: Exploring how international economic sanctions (do not) work. Oxford University Press.

Jones, L., & Portela, C. (2020). Evaluating the success of international sanctions: A new research agenda. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, 125, 39-60. https://tinyurl.com/54c27chy

Karagyozova, R. (2021, March 1). Iran’s tactics to evade the sanctions on its oil sector. IRAM Center for Iranian Studies. https://tinyurl.com/4exyszar

Kenez, L. (2023, February 28). Ukraine war anniversary: Turkish-Russian trade skyrocketed despite sanctions. Nordic Monitor. https://tinyurl.com/muhmtxba

Kharon. (2022). A North Korean sanctions evasion typology: Use of complex ownership structures. White Paper. https://tinyurl.com/mr3atmyy

Kim, S. J. (2021, December 14). North Korea’s sanctions evasion and its economic implications. Korea Institute for National Unification. https://tinyurl.com/3zzyzebh

Konowicz, D. R. (2028). The new game: Cryptocurrency challenges US economic sanctions. Naval War College Newport United States.

Korea, North. (2023). CIA World Factbook. https://tinyurl.com/ycx3rdvm

Lam, S. L. (1990). Economic sanctions and the success of foreign policy goals: A critical evaluation. Japan and the World Economy, 2(3), 239-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/0922-1425(90)90003-B

Laub, Z. (2015, July 15). International sanctions on Iran. Council on Foreign Relations. https://tinyurl.com/y27psz6t

Leali, G. (2022, February 25). France not opposed in principle to cutting Russia from SWIFT: Bruno Le Maire. Politico. https://tinyurl.com/mpehrjux

Lektzian, D., & Souva, M. (2007). An institutional theory of sanctions onset and success. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51(6), 848-871. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002707306811

Lipin, M. (2022, August 18). Tanker trackers: After Iraqi oil blending scheme, Iran found better way to evade US sanctions. Voice of America. https://tinyurl.com/bdethxtr

Lukaszuk, P. (2021). You can smuggle but you can't hide: Sanction evasion during the Ukraine crisis. Aussenwirtschaft, 71(1), 73-125.

Macfarlane, E. K. (2021). Strengthening sanctions: Solutions to curtail the evasion of international economic sanctions through the use of cryptocurrency. Michigan Journal of International Law, 42(1), 199-229. https://doi.org/10.36642/mjil.42.1.strengthening

Magas, J. (2019, November 26). BRICS nations discuss shared crypto to break away from USD and SWIFT. Cointelegraph. https://tinyurl.com/mp9ue9em

Mahmoudian, A. (2023, January 29). Russia’s financial defense mechanism against Western sanctions. Trends Research & Advisory. https://tinyurl.com/3aawr8yb

Mallory, K. (2021). North Korean sanctions evasion techniques. RAND Corporation. https://tinyurl.com/39k72utn

McDowell, D. (2021). Financial sanctions and political risk in the international currency system. Review of International Political Economy, 28(3), 635-661. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1736126

McMillan, R., & Volz, D. (2023, June 11). How North Korea’s hacker army stole $3 billion in crypto, funding nuclear program. Wall Street Journal. https://tinyurl.com/2rfs28z2

MI News Network. (2023, January 31). Russia following Iran’s cue, changes flag to evade US sanctions. Marine Insight. https://tinyurl.com/mr33xp3f

Ministry of Defense, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and Gavin Williamson. (2019, April 5). Royal navy vessel identifies evasion of North Korea sanctions. Gov.UK. https://tinyurl.com/ycknny27

Morgan, T. C., Bapat, N., & Kobayashi, Y. (2014). Threat and imposition of economic sanctions 1945–2005: Updating the TIES dataset. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 31(5), 541-558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894213520379

NEWS: OFAC targets Iran’s “shadow banking” network in new round of US sanctions. (2023, March 9). AML Intelligence. https://tinyurl.com/2p866bfw

Nikoladze, M., & Donovan, K. (2023). Russia Sanctions Database. Atlantic Council. https://tinyurl.com/vnzjufa9

O'Carroll, C., Jeongmin, K., & Won-Gi, J. (2021, August 20). South Korea detaining North Korea-linked ship suspected of sanctions violations. NK News. https://tinyurl.com/3sm2uc6y

Oesterreichische Nationalbank. (2022). The Russian economy and world trade in energy: Dependence of Russia larger than dependence on Russia.

Office of Foreign Assets Control. (2020, May 14). Guidance to address illicit shipping and sanctions evasion practices. U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://tinyurl.com/yw2jve9v

Okumura, Y. (2023, March 21). Examining the current state of Russian sanctions evasion. Dow Jones. https://tinyurl.com/29aprwau

Pape, R. A. (1997). Why economic sanctions do not work. International Security, 22(2), 90-136. muse.jhu.edu/article/446841

Peksen, D., & Jeong, J. M. (2022). Coercive diplomacy and economic sanctions reciprocity: Explaining targets’ counter-sanctions. Defence and Peace Economics, 33(8), 895-911. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.1919831

Ridgwell, H. (2023, June 6). Russia copying Iran to evade Western sanctions, report claims. Voice of America. https://tinyurl.com/3a7j9nc5

Rosenberg, E., & Bhatiya, N. (2020, March 4). Busting North Korea’s sanctions evasion. Center for a New American Security. https://tinyurl.com/mt2snd45

Russia and sanctions evasion. (2022). Strategic Comments, 28(4), vii-ix. https://doi.org/10.1080/13567888.2022.2107283

Sanctions against Iran. (n.d.). Sanction Scanner. https://tinyurl.com/ye22kxuw

Sharafedin, B., & Lewis, D. (2018, June 29). As sanctions bit, Iranian executives bought African passports. Reuters. https://tinyurl.com/554hwacs

Sossai, M. (2020). Legality of extraterritorial sanctions. In M. Asada (Ed.), Economic sanctions in international law and practice (pp. 62-73). Routledge.

Trainer, C. (2019, September 1). How North Korea skirts sanctions at sea. The Diplomat. https://tinyurl.com/3b3fz36h

Van Bergeijk, P. A. G. (1989). Success and failure of economic sanctions. Kyklos, 42(3) 385-404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1989.tb00200.x

Verma, N. (2013, November 7). Iran offers to ship crude to India for free to boost sales. Mint. https://tinyurl.com/2svy7ty9

Verma, N. (2018, July 26). Iran offers India oil cargo insurance, ships to boost sales: Sources. Reuters. https://tinyurl.com/yc2529yj

Watts, N. (2020, March 25). Business as usual, unusually: North Korea’s illicit trade with China and Russia. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. https://tinyurl.com/4kkypjw4

Wronka, C. (2022). Digital currencies and economic sanctions: The increasing risk of sanction evasion. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(4), 1269-1282. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-07-2021-0158

Yotov, Y., Yalcin, E., Kirilakha, A., Syropoulos, C., & Felbermayr, G. (2020, August 4). The global sanctions data base. VoxEU. https://tinyurl.com/47834rza

Yotov, Y., Yalcin, E., Kirilakha, A., Syropoulos, C., & Felbermayr, G. (2021, May 18). The “global sanctions data base”: Mapping international sanction policies from 1950–2019. VoxEU. https://tinyurl.com/3ufpfpj2

Young, B. (2021, February 4). North Korea in Africa: Historical solidarity, China's role, and sanctions evasion. United States Institute of Peace. https://tinyurl.com/48yj7sa4

Zandt, F. (2023, February 22). The world's most-sanctioned countries. Statista. https://tinyurl.com/yzyv3k48

[1] Articles on State Responsibility (ASR) is a document that details international law regarding a state’s responsibility when it comes to violating international obligations, which was adopted by the UN’S International Law Commission.