Strategic Assessment

East Jerusalem Palestinians claim that Israeli policy in the city over the course of the last two to three decades has had the dual aim of cutting off this population from the West Bank and destroying any sense of their Palestinian national identity. They claim that this policy has not only been largely successful in achieving these aims, but has also led to economic underdevelopment, pessimism about the future, and political apathy. In turn, and in effort to fill the void developed by these feelings, they argue that many East Jerusalem Palestinians have become more religiously extreme, and in some cases, more violent. This paper seeks to examine these claims with an empirical approach. It first outlines the Israeli policies that are said to have encouraged this situation and then analyzes public opinion data. While the study supports many of the claims by these East Jerusalem Palestinians, it also reveals some positive trends. The paper then proposes policy recommendations to improve socioeconomic conditions in East Jerusalem, reduce religious extremism, and thereby to reduce terrorist attacks against Israelis.

Keywords: Palestinians, East Jerusalem, religiosity, terrorism, Plan 3790, citizenship

Introduction

A sample of East Jerusalem Palestinians interviewed for this study contend that Israeli policy in the city over the course of the last 20 to 30 years has had two primary objectives: one, to cut off East Jerusalem Palestinians from Palestinians in the West Bank; and two, to destroy any sense of Palestinian national identity among this population.[1] And while they refer to “Israeli policy” in general terms, literature produced by the Palestinian third sector in East Jerusalem, in addition to work by Israeli organizations positioned on the political left in the country, including but not limited to Ir Amim and Peace Now, suggests that four specific policies underlie their sentiments:[2]

- Construction of the post-1967 neighborhoods in East Jerusalem

- The separation barrier

- The portion of the municipal budget allocated to Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem

- Israeli policies regarding education in East Jerusalem

They further argue that these policies have been largely effective in achieving the two primary objectives outlined above. But they also claim that in East Jerusalem, these policies have led to economic underdevelopment, political apathy, and pessimism about the future, particularly among the youth in the city.

The result, according to these East Jerusalem Palestinians, has been a growing number of young individuals in East Jerusalem without a clear direction in their lives, seeking some kind of meaning. They argue that many of these individuals have found meaning through religion and the al-Aqsa Mosque in particular, which they claim has come to symbolize the Palestinian national movement. They argue that al-Aqsa is so significant for these East Jerusalem Palestinians because it not only represents the national movement, but also a religious site and symbol that no Israeli policy has been able to take from them. As such, when Israel, prompted by security circumstances, does take actions at al-Aqsa—such as imposing restrictions on prayer or interrupting worshipers there—East Jerusalem Palestinians are provoked, fearful of Israel destroying the last remaining vestiges of their national identity.

This story that these East Jerusalem Palestinians tell is logical, but is based on their sense of the situation in East Jerusalem and is not empirically validated—which would require, at minimum, answering the following five questions:

- Do the residents of East Jerusalem suffer from economic underdevelopment?

- Do the residents of East Jerusalem demonstrate a lack of trust in government and authority figures?

- Are the residents of East Jerusalem politically apathetic?

- Has there been an increase of individual religiosity and the importance of al-Aqsa among East Jerusalemites over the last 20-30 years?

- Has there been an increase in terrorist attacks emanating specifically from East Jerusalem?

The primary purpose of this article is to answer these questions. It first describes the four policies referenced above that may well have contributed to the socioeconomic outcomes in East Jerusalem implicated by these five questions. It then provides public opinion data related to the first four of these five questions, followed by longitudinal data about terrorist attacks in Jerusalem from 2000 to 2023, with a focus on the years 2010-2023. The evidence indicates that largely, the answer to the five questions referenced above is “yes.” In short, most, if not all, of the elements of the story told by East Jerusalem Palestinians are validated. And as such, a secondary purpose of this article is to offer two specific policy recommendations that the Israeli government can undertake to counteract the economic underdevelopment, social and political apathy, and increased religious extremism in East Jerusalem—with the goal of reducing terror attacks against Israelis and improving the country’s security.

Policies and Outcomes

This section focuses on four Israeli policies regarding East Jerusalem, and then describes the conditions of the Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem.

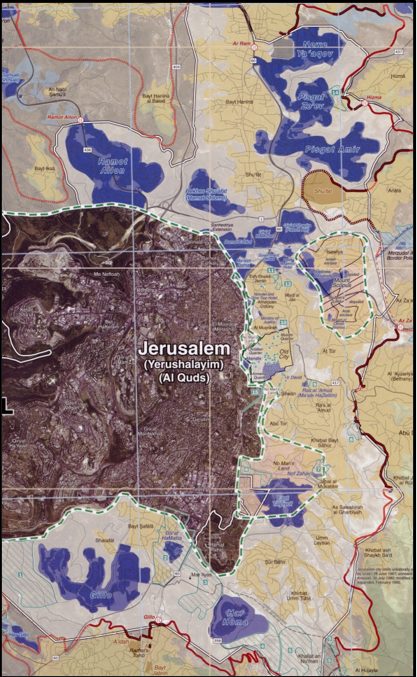

New Israeli Neighborhoods and Expansion

Since 1968, Israel has built 13 new neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, with the last of them, Har Homa, completed in 2002.[3] If so, why would these neighborhoods have a more recent impact on today’s East Jerusalem’s Palestinians, different from when they were built? The answer is twofold. First, these neighborhoods have come to be known as the “ring neighborhoods” of the city because they form a ring around West Jerusalem and isolate the Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem. For example, the Palestinian neighborhoods of Shuafat and Beit Safafa, located to the north and the south of the city, respectively, have been effectively cut off from the West Bank by the Israeli neighborhoods of Gilo and Givat HaMatos. Figure 1 provides a map of these “ring neighborhoods,” compiled by the United States Central Intelligence Agency. The dark brown area represents West Jerusalem, the beige represents Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, and the blue represents the “ring neighborhoods.” Some minor additional areas appear in blue in this map (e.g., “Government Offices”), but the key point is that these neighborhoods form a ring around West Jerusalem.

Figure 1: West and East Jerusalem, and “ring neighborhoods” | Source: Library of Congress, 2006

Second, and more important, while Israeli building in these neighborhoods has continued over the years, Palestinian expansion has not matched that pace. Specifically, of the 57,737 housing units approved in construction permits in Jerusalem from 1991-2018, 16.5 percent (9,536) were approved for construction in Palestinian neighborhoods, while 37.8 percent (21,834) were approved for construction in Israeli neighborhoods over the Green Line and 45.7 percent (26,367) were approved for construction in West Jerusalem (Peace Now, 2019). These trends have continued more recently as well, with 23,097 settlement plans and tenders approved for Israeli neighborhoods over the Green Line in 2022,[4] representing a 58.19 percent year-over-year increase, and almost 300 percent increase since 2017. However, many of the plans advanced in 2022 were for urban renewal,[5] and therefore may not actually expand the neighborhoods territorially (European Union, 2023).

The Security Barrier

During the height of the second intifada, and with the stated goal of curbing the wave of terror emerging from the West Bank, Israel began constructing the security barrier. The erection of the barrier contributed to a decrease in the number and frequency of terror attacks against Israelis (Dumper, 2014). However, by virtue of the route there was a lack of congruence between the Jerusalem municipal boundary and the barrier itself (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Separation barrier in the Greater Jerusalem area | Source: Ir Amim, 2017

This resulted in two types of enclaves: areas outside the security barrier but within the municipal boundary of the city; and those areas within the security barrier but not included in the city’s jurisdiction.

Prominent enclaves outside the fence and within the city’s municipal jurisdiction, with a population of between 120,000 and 140,000 (Koren, 2019) include:

- The vicinity of Walaja in southern Jerusalem—500 dunams (125 acres), including residences.

- A 900 dunam area (225 acre) that contains the entire Shuafat refugee camp and the neighborhoods of Ras Khamis, Ras Shahada, and Hashalom. Construction in this area is very dense, with many buildings.

- A 1,300 dunam area (325 acres) in northern Jerusalem that includes all of Kufr Aqab, al-Matar, Za’ir, and Qalandia.

Those areas inside the barrier but outside the municipal boundary amount to 9,690 dunams and are home to approximately 7,000 residents, and include the areas of Har Gilo, Wadi Hummus, and the area east of the Neve Yaakov neighborhood (Koren, 2019).

Budget Allocation to Palestinian Neighborhoods of East Jerusalem

Both Israelis and Palestinians alike recognize that relative to neighborhoods of similar size in Israel, Palestinian East Jerusalem neighborhoods have consistently been allocated minimal budgets (Asmar, 2018). For example, in 2013, the NGO Ir Amim estimated that between 10.1-13.6 percent of the municipal budget was invested in East Jerusalem, despite that part of the city representing approximately 36.9 percent of the population of the city (Ir Amim, 2014). In 2018, largely based on the understanding that maintaining sovereignty in East Jerusalem would mean taking responsibility for the locals’ quality of life, Israeli policymakers aimed to address these disparities in the municipal budget. They adopted Plan 3790, which allocated NIS 2.2 billion (approximately $630 million) over the course of five years to ten different sectors, led by education and higher education; economy and employment; transportation; civil services and quality of life; healthcare; and land registration in East Jerusalem (Dagoni, 2022). Since its inception, Plan 3790 has produced tangible improvements in East Jerusalem such as: the so-called American Road that connects the neighborhoods in the city’s southeast with an extensive transportation infrastructure that until now was present only in West Jerusalem; the well-equipped Alpha School in Beit Hanina; and a new public park behind Herod’s Gate (Hasson, 2019). Plan 3790 expires at the end of 2023, and as of May 22, 2023, a new, bigger plan with similar goals and a budget of NIS 4 billion had been removed from the cabinet’s agenda, largely due to opposition from Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich. Professionals familiar with the plan, however, predict that there will be a new, better plan that will be adopted and that “this [removal] will prove to be a small pothole in the road” (Hasson & Freidson, 2023).

Education in East Jerusalem

There are five kinds of schools in East Jerusalem, two of which—Manchi (municipal) schools and informal recognized schools—receive financial support from the Israeli Ministry of Education. Manchi schools are fully funded and managed by the Jerusalem Municipality and the Israeli Ministry of Education, while informal recognized schools receive up to 75 percent of their budgets. Awqaf schools, private schools, and UNRWA schools do not receive any support from the Israeli government (Alayan, 2019; Alian, 2016; Nuseibeh, 2015). As of 2022, of the 143,221 school-age children (ages 3-18) in East Jerusalem (Education Authority, 2022), 102,921 were enrolled in either Manchi schools or informal recognized schools (Ir Amim, 2022).

As of 2013, of those Jerusalem schools that were funded by the Israeli Ministry of Education, students in state religious schools received the highest annual budget (NIS 25,500 per student), followed by Jewish students in public schools (NIS 24,500), followed by ultra-Orthodox (haredi) (NIS 19,600), and finally, East Jerusalem Palestinian students (NIS 12,000) (Alayan, 2019). Recognizing these vast disparities, over the last 15 years, Israel has demonstrated a greater commitment to increase funding to East Jerusalem schools, culminating with Plan 3790 in 2018, of which NIS 445 million were allocated to the East Jerusalem education system over the course of five years. This funding was allocated according to the following breakdown: NIS 18.3 million for pedagogic guidance, oversight, and enforcement; NIS 68.7 million designated for special programs in institutions teaching the Israeli curriculum; NIS 57.4 million for physical development of institutions teaching the Israeli curriculum; NIS 206 million for technology education; and NIS 67 million for rental of buildings for educational institutions teaching the Israeli curriculum (Abu Alhlaweh, 2018). In addition to this NIS 445 million allocated to the East Jerusalem education system, Plan 3790 allocated NIS 275 million to higher education for East Jerusalem Palestinians (Dagoni, 2022).

Conditions in Palestinian Neighborhoods in East Jerusalem

What outcomes have these four policies generated in East Jerusalem? Four main themes that emerge on the socioeconomic conditions in these neighborhoods are a lack of space; a lack of effective infrastructure; a lack of public services; and uncertainty about the future of some recent positive developments in education for East Jerusalem Palestinians.

First, Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem suffer from a lack of space, the result of two of the policies outlined above: the expansion of Israeli neighborhoods in East Jerusalem and the construction of the separation barrier. As the expansion of Israeli neighborhoods greatly outpaces that of Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, it compromises the available space for the city’s Palestinians. In addition, many of the residents who live in neighborhoods beyond the separation barrier but within the municipal boundaries of the city have jobs that are inside the city. According to Michael Dumper, the result is that many[6] have moved to neighborhoods within the separation barrier. Further, the combination of a lack of space and increased population density in these neighborhoods has decreased the supply of available housing and increased the demand, resulting in a drastic increase in housing prices—by as much as 45 percent in some neighborhoods (Dumper, 2014).

East Jerusalem Palestinians are acutely aware of these trends. Fuad Abu Hamed, an East Jerusalem Palestinian who is a social activist and lecturer at the Jerusalem Business School at Hebrew University, and director of an HMO in East Jerusalem, has said that “there is tremendous housing distress, and people are constantly talking about how they have to move out” (Hasson, 2021). And while the lack of space in East Jerusalem neighborhoods is most acutely felt within the sphere of housing, it also limits the availability of public spaces such as parks, playgrounds, sports facilities, and most importantly, schools (Jerusalem Institute, 2019b). As of 2021-2022, for example, the Municipality estimated that there were 2,000 missing classrooms in East Jerusalem, while Ir Amim claimed that 3,517 were missing (Ir Amim, 2022).

In addition, Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem lack effective infrastructure and public services. Both of these shortcomings stem from the lack of sufficient funds from the municipal budget invested in East Jerusalem. In terms of infrastructure, residents complain of a lack of curbsides and sidewalks, and that many homes are not connected to the sewage system or water supply. With regard to public services, family care centers, post offices, and banks are singled out (Jerusalem Institute, 2019b). These lapses could be corrected significantly by investing more money in East Jerusalem—for example, by the Municipality hiring more sanitation workers to help with sewage. Plan 3790, with its investment of NIS 2.2 billion in East Jerusalem, made that clear, with one East Jerusalem Palestinian claiming that “anyone with eyes in his head can see that there is a change in terms of infrastructures, a situation that didn’t exist before” (Hasson, 2019). The progress made by Plan 3790, however, is threatened by Minister Smotrich’s decision to remove the larger plan slated to begin in 2024 from the cabinet’s agenda.

In contrast, while not a physical condition, recent, positive outcomes with regard to education in East Jerusalem have emerged in the last few years. Prior to 2018 and the implementation of Plan 3790, two main issues plagued the successful integration of East Jerusalem Palestinian students into Israeli universities, and in turn, the Israeli economy. First, Palestinians and Israelis alike recognized that Hebrew instruction in East Jerusalem was “seriously deficient,” with many students barely learning the alphabet despite multiple years of instruction (Khader, 2021). Second, Israeli universities did not recognize the tawjihi, the Palestinian Authority’s matriculation exam. The result was that East Jerusalem Palestinian students chose to study either at universities in the West Bank such as Birzeit University, or for those with the means, universities in other Arab countries. In either case, the result was a wider gap between East Jerusalem and Israeli society due to decreased interaction in higher education, and subsequently, in the labor market.

This changed significantly with the implementation of Plan 3790 in 2018. First, 3790 put a strong emphasis on boosting the study of Hebrew in East Jerusalem schools both in terms of instruction and results. Some Palestinian parents have objected to this effort, arguing that the objective is to encourage the “Israelization” of the eastern part of the city. Yet nationalist feelings aside, the current economic reality is that Jerusalem is a bi-national city, with a more thriving Western, Israeli area. If individuals want to be competitive in that labor market, they must be able to communicate in the dominant language—Hebrew. Second, the implementation of Plan 3790 coincided with two major policy changes that eased funding and admission restrictions to Israeli universities in Jerusalem, most prominently, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI). First, funding from the Council for Higher Education enabled Israeli universities to offer stipends to nearly every Palestinian who met the requirements for entrance to these schools, allowing many more to study there. Fuad Abu Hamed underscored the importance of these stipends, explaining that “there’s no doubt that funding and attention paid by Israeli institutions were major factors [since] now any child, even if he or she is poor, can get in as long as his/her grades are good” (Hasson, 2019). Second, HUJI began to recognize the tawjihi, eliminating the need for qualified Palestinian students to complete a year-long preparatory program for admission.

At HUJI in particular, these policies yielded immediate benefits, with 278 East Jerusalem Palestinians completing the pre-matriculation preparatory program in 2019—corresponding to approximately 54.4 percent year-over-year growth. The statistics for those studying at HUJI during the same period were similarly impressive, with 161 students and a 54.8 percent year-over-year growth rate. These numbers have continued to balloon since then, with 710 Palestinian students studying at HUJI in 2022 (Cidor, 2022). These positive developments in education for East Jerusalem Palestinians face an imminent and major threat from Finance Minister Smotrich, whose opposition to 3790 stems largely from the provisions encouraging higher education for East Jerusalem Palestinians (Hasson & Freidson, 2023).

Taken together, the current picture that emerges from Israeli policies in East Jerusalem is largely bleak. These policies seem to have contributed to at least four socioeconomic outcomes in East Jerusalem: a lack of space, a lack of effective infrastructure; a lack of public services; and uncertainty about labor market outcomes and improved educational opportunities for East Jerusalem Palestinians. On an individual level, these outcomes have presumably created economic stress among many Palestinians in East Jerusalem related to the housing crisis, a poor quality of life stemming from the lack of public space and services, and a potential roadblock to improved educational and future economic opportunities.

Public Opinion in East Jerusalem

Following the survey of the economic distress and challenging life conditions in East Jerusalem, and the four Israeli policies that may have contributed to these outcomes, this section looks at East Jerusalem public opinion, based on four sources.

The first, the Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem, released annually by the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research since 1982, is a respected database compiling statistical data about Jerusalem. It relies primarily on data from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and the Jerusalem Municipality.[7] The second is Arab Barometer, which describes itself as a “nonpartisan research network that provides insight into the social, political and economic attitudes of ordinary citizens across the Arab world” (Arab Barometer). Arab Barometer data are from Palestinian and Arab sources and include additional data not contained in the Statistical Yearbooks, such as individual religiosity. The local partner responsible for data collection in East Jerusalem and the West Bank for the Arab Barometer is the Palestine Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR), headed by Dr. Khalil Shikaki (Arab Barometer Technical Reports from Wave II- Wave VII). Third are the results of a “A Special East Jerusalem Poll” conducted in November 2022 by Dr. Shikaki. While the Arab Barometer data are collected by PCPSR, this survey is not in the Arab Barometer data; it focuses specifically on East Jerusalem; and it is based on a random sample of 1000 respondents—a much greater number of respondents than the average of 158.4 from East Jerusalem in the Arab Barometer from 2010-2021. Fourth are the results of a June 2022 survey commissioned by Dr. David Pollock of the Washington Institute and conducted by the Palestine Center for Public Opinion. This poll was conducted from June 6-21, 2022, with a sample of 300 Palestinian adult legal residents of East Jerusalem within its official municipal boundaries (Pollock, 2022).

In consolidating the data from these four sources to present the results most relevant to the research questions posed in this article, the data are organized around three central themes: economic trends; political and social trends; and religiosity.

Economic Trends

Suggested above is that the poor economic situation in East Jerusalem is related to two primary factors: one, the housing crisis stemming from the expansion of Israeli neighborhoods in the area and the separation barrier and two, the inability of East Jerusalem Palestinians to turn educational gains into better labor market outcomes taken together with the specter of the reduction of educational funding for them. PCPSR’s East Jerusalem poll provides further support for the first conclusion, indicating that the percent of respondents claiming that among what they like least about living in East Jerusalem, “the economic situation and the high cost of living,” increased from 3.9 percent in 2010 to 6.1 percent in 2023, or a 56.41 percent increase (PCPSR, 2022). It also provides some support for the second conclusion, with the proportion of respondents claiming that they are “very concerned” about “Losing access to adequate education [for] my children,” increasing from 31.6% in 2010 to 34.0% in 2022 (PCPSR, 2022).

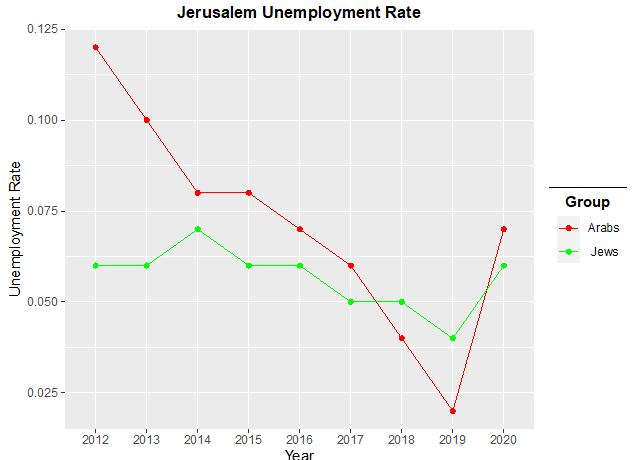

The Statistical Yearbooks, published by the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, provide data on employment and poverty in East Jerusalem, adding to the assessment of the economic situation there. At first glance, the data from the Statistical Yearbooks suggest that employment in East Jerusalem is improving. The data show that early in the previous decade, the unemployment rate among the Palestinians in Jerusalem was 10-12 percent (Jerusalem Institute, 2014, 2015). Since then, however, the unemployment rate in Jerusalem among both Jews and Palestinians has declined steadily—apart from the increase that occurred in 2019-2020, among both Jews and Palestinians, likely as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The general positive trends described above associated with the unemployment rate in Jerusalem, and particularly among the East Jerusalem Palestinians are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Unemployment rate in Jerusalem | Source: Jerusalem Institute, 2014-2023

This improving unemployment rate, however, masks other problematic trends in the data. Consider the definition of “employed” used in the underlying data from CBS’s Labor Force Surveys (Jerusalem Institute, 2022):[8]

Employed—Persons who worked during the determinant week at any job for at least one hour, for pay, profit or any other renumeration; family members who worked unpaid in a family business; persons in institutions who worked for 15 hours or more per week; and persons who were temporarily absent from their usual work.

This means that if someone worked for one hour per week and was not looking for work, he would be considered “employed” and not “unemployed.” This may at least partially explain that despite the significant improvements in the unemployment rate among East Jerusalem Palestinians in 2012-2020, the population experienced very high poverty rates.

The countries with the highest poverty rates in the world as of 2023 were led by South Sudan at 82.30 percent, with Guatemala in tenth place, at 59.30 percent (World Bank, 2023a). In the United States, approximately 11.6 percent of the population lives in poverty (Lee, 2023). In comparison, among Palestinian children in Jerusalem during the period 2011-2020, approximately 79.9 percent were living in poverty. Among adults, which are distinguished from children and the elderly population in the data, that same figure was 72.8 percent. Finally, among families, the figure was 70.0 percent. Each of these categories demonstrated significant declines during the period, with the poverty rate among children declining from 86 percent in 2011 to 70.3 percent in 2020, among adults from 81 to 61.4 percent, and among families from 75 to 57.3 percent (Jerusalem Institute, 2014-2023). Yet the improved rates among East Jerusalem Palestinians would still place them among the most impoverished nations in the world.

The poor economic situation of the Palestinians in Jerusalem from the Statistical Yearbooks/CBS data is corroborated by Arab Barometer data and mirrors the results presented by the PCPSR poll, with respondents very concerned about the economic situation. Specifically, during the period 2010-2021, when asked, “What is the most important challenge facing Palestine today,” in four out of the five rounds of surveys, the greatest portion of East Jerusalem Palestinians said that it was the economic situation (in 2022, they said it was security and stability), with an average proportion of 34.33 percent citing this challenge over the period (Arab Barometer, 2009-2022).

In the context of the economic concerns of East Jerusalem Palestinians—likely in part due to their not working enough hours—the nature of their employment presumably does not pay them enough, despite a relatively high rate of higher education among this population. Specifically, during the period 2012-2021, according to the Statistical Yearbooks/CBS data, some 63.3 percent of the workforce held a Bachelor’s degree, with 72.9 percent holding a Master’s degree. The corresponding percentages for the Jewish population of Jerusalem were 88.9 percent and 90.9 percent, respectively (Jerusalem Institute, 2014-2023). Given these figures, we would expect the Jewish population of Jerusalem to have more prestigious and higher paying jobs—and they do. However, given the relatively high rate of higher education among East Jerusalem Palestinians, the gap between East Jerusalem Palestinians and Israeli Jews in these high paying and prestigious jobs should not be as large as it is. For example, during the period 2017-2021,[9] the average proportion of Jewish residents of Jerusalem working in hi-tech was 8.0 percent, while among Arabs it was 0.9 percent. In addition, among the Jewish population, there was approximately a 12 percent year-over-year growth in employment in the hi-tech sector during this period, while among the East Jerusalem Palestinians, there was evidence of decline. Similarly, the average proportion of Jews employed in academia during the period from 2012-2021 was 37.2 percent, while East Jerusalem Palestinians were employed at a rate of 15.8 percent. Yet for the same period, the proportion of East Jerusalem Palestinians employed in unskilled labor had an average of 18.0 percent, while for Jews, the average was 7.1 percent (Jerusalem Institute, 2014-2023). In short, the figures suggest that among those East Jerusalem Palestinians who are working, despite being highly educated, many of them may be settling for less prestigious, poorer paying jobs.

It would be wrong to say that these data offer an entirely depressing picture of the economic situation in East Jerusalem. They do clearly show a declining unemployment rate, and reductions in the high rate of poverty in that part of the city. Nonetheless, people are still very concerned about their economic situation and poverty rates remain high, largely as a result of two primary factors. First, the housing crisis in East Jerusalem Palestinian neighborhoods stemming from the expansion of Israeli neighborhoods there and the separation fence continues to take a toll in terms of rising prices and limited space. Second, despite some progress in education in East Jerusalem, there is evidence that the population has not successfully translated their educational advancement into economic gains in the labor market. Also significant is the specter of a reduction of funds for this educational advancement among East Jerusalem Palestinians on account of Finance Minister Smotrich’s opposition to what amounts to the continuation and expansion of Plan 3790. Further, the possibility of this funding cut exists despite the promising gains made specifically within higher education among East Jerusalem Palestinians during 2018-2023 and associated with the funding from Plan 3790.

Political and Social Trends

Given the Israeli policies and conditions in East Jerusalem neighborhoods, coupled with the economic trends described, one would expect to see either political apathy or mass political mobilization, distrust, and social frustration. Indeed, politically, the data tend to demonstrate greater political apathy. Beginning in the Statistical Yearbook of 2022, the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research began to provide survey data on public views related to the performance of public institutions including the government, healthcare system, education system, and police. Table 1 provides the public function followed by the percentage of respondents that answered “not so much” or “not at all.” In other words, high percentages here are bad.

Table 1: Jerusalem Arabs and “Jews and others”: Trust in particular public authority—“not so much” or “not at all”

| Public Function | Arabs | Jews and others |

| Trust in the government | 80.0% | 55.0% |

| Trust in the justice system | 54.0% | 57.0% |

| Trust in the health system | 9.0% | 24.0% |

| Health system functioning | 10.0% | 37.0% |

| Education system functioning | 37.0% | 53.0% |

| Knesset functioning | 88.0% | 82.0% |

| Municipality Functioning | 76.0% | 45.0% |

| Police Functioning | 64.0% | 54.0% |

Source: Jerusalem Institute, 2022

Table 1 underscores that during the period 2018–2020, East Jerusalem Palestinians had little faith in the three main Israeli political institutions meant to serve them: the government, the Knesset, and the municipality. The East Jerusalem Palestinians’ dissatisfaction with these political institutions was particularly high relative to the “Jews and others” category, with the exception of trust in the Knesset.

This lack of trust in Israeli political institutions among East Jerusalem Palestinians gains greater weight with the results of PCPSR’s East Jerusalem Poll. The findings of this survey focus on the Jerusalem municipality and demonstrate a “total absence of trust in [its] intentions” (PCPSR, 2022). More precisely, when asked about the “goals” of “the municipality of Jerusalem…for [the] next few years,”[10] from 2010 to 2022, the proportion of respondents claiming that their goals were to “build new residential neighborhoods for the Arabs and improve the level of municipal service delivery to them” increased 0.1 percentage points from 1.3 to 1.4 percent. Also on the positive side, for the same period, the percentage of respondents claiming that their goals were to “introduce some improvements in the level of municipal service delivery to the Arabs” increased 1.1 percentage points, from 2.5 to 3.6 percent (PCPSR, 2022).

These positive developments, however, were greatly overshadowed by the negative responses in the survey, with an increase of 3.3 percentage points of respondents, from 6.2 to 9.5 percent, who claimed that the Municipality’s goal was to “reduce the level of municipal service delivery or the Arab residents.” And most telling was that an overwhelming 64.3 percent of respondents in 2022 believed that the goal of the Municipality was to “demolish Arab homes and neighborhoods, evict Arab residents, and reduce the level of municipal services” (PCPSR, 2022). The proportion of respondents selecting this choice dropped 1.6 percentage points from 65.9 percent in 2010; however, this decrease holds far less weight, considering that the overwhelming majority of respondents selecting this answer in both 2010 and 2022.

In addition to a lack of trust in Israeli political institutions, both the PCPSR poll and Arab Barometer point to “distrust in the PA and its institutions” (PCPSR, 2022). Distrust in the PA among Palestinians is certainly not a new phenomenon; however, Palestinians argue that this distrust among East Jerusalemites peaked in 2021 when Israel decided to prevent their participation in Palestinian general elections that year and the PA acquiesced by canceling them. As support for this claim, PCPSR points to two results. First is the high proportion (53.9 percent) of East Jerusalem Palestinians claiming that the level of corruption among PA officials is a “very big problem.” Second is the decrease in proportion of East Jerusalemites preferring Palestinian sovereignty in East Jerusalem (from 51.8 percent in 2010 to 38.0 percent in 2022) in the event of a negotiated settlement and the increase in those preferring Israeli sovereignty (from 6.1 percent in 2010 to 19.2 percent in 2022) (PCPSR, 2022).

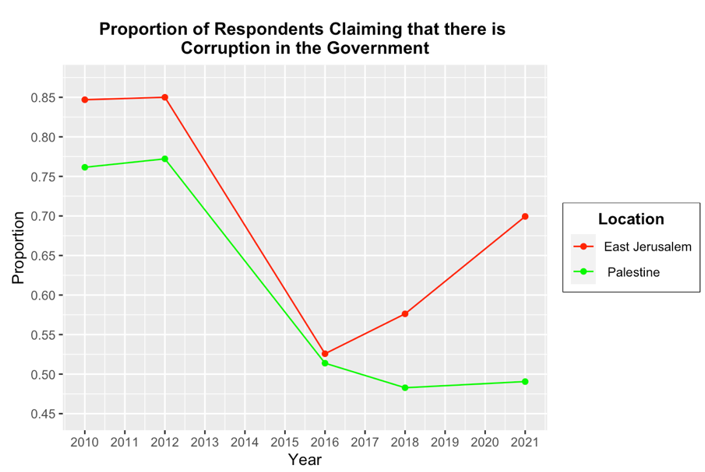

While Arab Barometer does not examine preferences among East Jerusalemites in the event of a negotiated settlement, it does ask about corruption in the PA. In addition, unique to the Arab Barometer data is the ability to compare the responses of East Jerusalemites to those Palestinians in the West Bank—a population demographically similar but living under different condition (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Belief there is corruption in government | Source: Arab Barometer, 2009-2022

The most significant trend in Figure 4 is that despite the demographic similarities between East Jerusalem and West Bank Palestinians, since 2016, the proportion of East Jerusalemites claiming that there is corruption in the PA has increased, while the proportion in the West Bank has remained steady. Furthermore, these results support those from the PCPSR data and the claims made there, namely, that belief about corruption in the PA among East Jerusalemites peaked in 2021 with its decision to cancel elections.

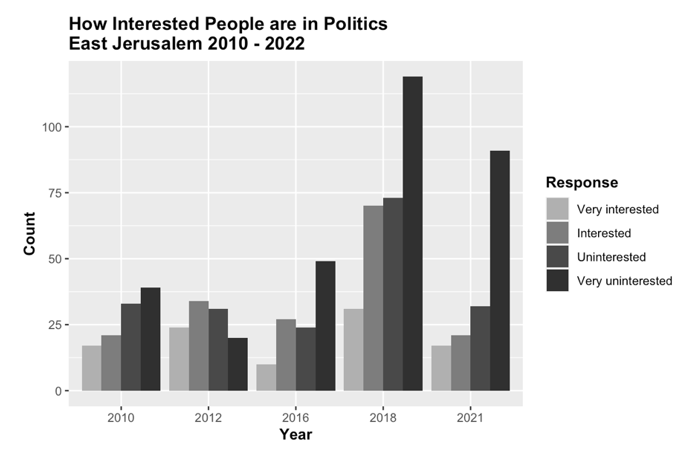

The key point here is that whether it is the Israeli government or the PA, East Jerusalem Palestinians do not appear to trust government or its institutions. Perhaps predictably, this distrust has been accompanied by general political apathy, hopelessness, and alienation among East Jerusalem Palestinians. For example, the proportion of East Jerusalem Palestinians that did not participate in the last Palestinian parliamentary or presidential elections (in which they had a chance to vote) increased drastically from 78.3 percent in 2010 to 93.2 percent in 2022. And among those from the 2022 poll that answered that they did not participate, 41.3 percent claimed it was because they were “not convinced with the candidates,” 24.2 percent claimed that it was because “participation was pointless,” and 13.7 percent because the “winners, no matter who they were, could not possibly serve East Jerusalem” (PCPSR, 2022). This political apathy, hopelessness, and alienation is also demonstrated in the Arab Barometer data, which explicitly asked respondents, “In general, to what extent are you interested in politics?” (Figure 5). Note that this question did not focus on any one particular political body, but “politics” in general.

Figure 5: Interest in Politics, East Jerusalem | Source: Arab Barometer, 2009-2022

Figure 5 demonstrates that East Jerusalem Palestinians have become more politically “uninterested” and “very uninterested,” specifically in the years 2018 and 2021, which correspond to the longitudinal trends presented in the data above.

While these data are indicative of greater political frustration and apathy among East Jerusalem Palestinians, the data on social trends offer a more complex story. First, in 2010-2022, there was an 11-percentage point increase among East Jerusalem Palestinians who claim to perceive threats and intimidation from Israeli police and Border Police. And there has been a similar 10-percentage point increase among East Jerusalem Palestinians who claim to have perceived a threat from Jewish settlers (PCPSR, 2022). Given the Israeli policy of expanding Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, these percentage point increases are not surprising.

At the same time, there have also been strong improvements in the percentage of East Jerusalem Palestinians claiming that they are satisfied with the services provided to them in their neighborhoods. These trends are clear from the data in the Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook of 2022 presented above and with regard to healthcare in particular, in which only 9.0 percent express distrust in the health system and 10 percent are not satisfied with its functioning (far more positive figures than from among the Jewish population, at 24.0 percent and 37.0 percent, respectively) (Jerusalem Institute, 2022). These figures are corroborated by those from the PCPSR survey in which 83 percent of East Jerusalem Palestinians claimed that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the delivery of healthcare services in their neighborhood. Further, the PCPSR survey makes clear that East Jerusalem Palestinians were satisfied with many municipal services in 2022, including: water (82 percent), electricity (75 percent), the sewage system (73 percent), the speed with which fire rescue services arrive (70 percent), and the speed with which ambulance services arrive (69 percent), among others. Relative to 2010, East Jerusalem Palestinians demonstrated greater satisfaction with 21 municipal services, in comparison to a decline in satisfaction with just 5, with the most significant decline being the supply of electricity, which is in fact not the responsibility of the Jerusalem Municipality (PCPSR, 2022). Yet while these 21 improvements are encouraging, they are relative to the opinions expressed in 2010, and many of them—while better—are still far from satisfying a majority of East Jerusalem Palestinians.[11]

Third, and most surprising, both the PCPSR data and the June 2022 survey commissioned by the Washington Institute suggest that a greater number of East Jerusalem Palestinians are open to Israeli citizenship. The PCPSR survey demonstrates that 19 percent of the respondents prefer Israeli sovereignty in East Jerusalem, while 38 percent prefer Palestinian sovereignty—a 13 percentage point increase in favor of Israel and a 14-percentage point decrease against Palestinian sovereignty. Then, when asked whether they would prefer Palestinian or Israeli citizenship in a permanent settlement, 58 percent (compared to 63 percent in 2010) said they would want Palestinian citizenship, while 37 percent (compared to 24 percent in 2010) said they would want Israeli citizenship (PCPSR, 2022). The results from Pollock’s data are even more pronounced, with 48 percent of respondents saying that they would prefer to become citizens of Israel, versus 43 percent choosing Palestine. According to Dr. Pollock, this is a new development, since the percent that chose Israeli citizenship in 2017-2020 “hovered around just 20%” (Pollock, 2022).

Three political and social trends emerge from the data surveyed. First, East Jerusalem Palestinians are politically frustrated and apathetic. Second, while there have been significant improvements in quality of life and public services recently, there is still much work to do. Third, an increasing number of East Jerusalem Palestinians are open to the idea of accepting Israeli citizenship.

Religiosity and al-Aqsa

Neither the PCPSR survey nor the Washington Institute survey contains any questions about religiosity. The data from the Statistical Yearbooks from the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research do provide the number of individuals belonging to a certain religion in Jerusalem, but do not provide ways to identify any measure of individual religiosity. Arab Barometer, however, includes a question worded as follows: “In general, would you describe yourself as religious, somewhat religious, or not religious?” (Arab Barometer, 2009-2022). Answers to this question suggest that there has been a sharp increase in the level of religiosity among East Jerusalem Palestinians during 2010-2021.

As with the issue of governmental corruption, the data on religiosity from East Jerusalem is presented with data from the West Bank, on the assumption that this group should be similar demographically to those individuals living in East Jerusalem, albeit living under different conditions. In the case of individual religiosity, this comparison group is particularly informative since the data suggest that while there has been a sharp increase in the level of individual religiosity among East Jerusalem Palestinians in 2010-2021, the level of individual religiosity among those living in the West Bank has remained relatively constant. This suggests that there may be something underway in East Jerusalem that is not occurring in the West Bank that may influence the levels of individual religiosity in different ways.

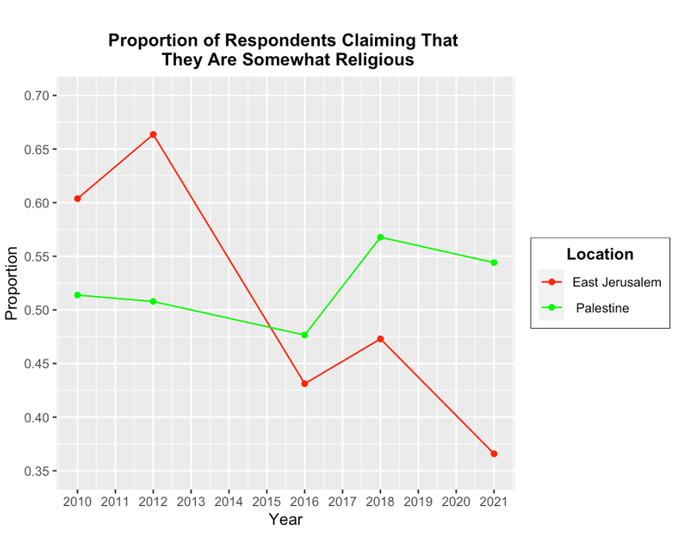

The increase in individual religiosity among East Jerusalem Palestinians is empirically verified from the data from the Arab Barometer from two of the responses to the question listed above. First, and somewhat counterintuitively given the claims of the Palestinians in East Jerusalem, the data from Arab Barometer demonstrate that the number of respondents self-identifying as “somewhat religious” during the period from 2010-2021 has decreased sharply, as is clear in Figure 6:

Figure 6: Religious self-identification: “somewhat religious” | Source: Arab Barometer, 2009-2022

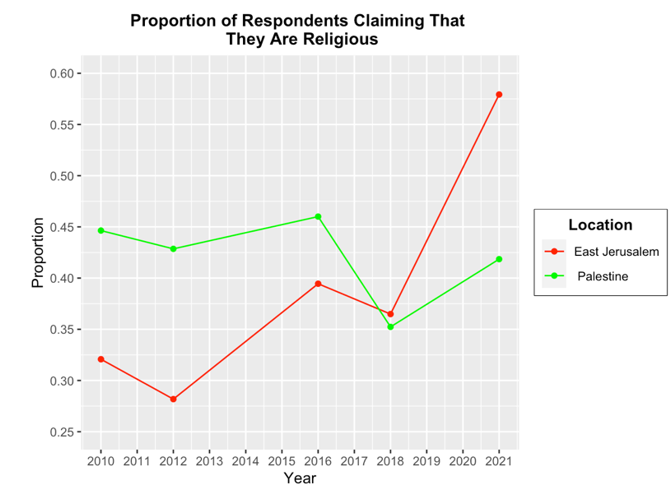

By itself, Figure 6 suggests that the claims of East Jerusalem Palestinians that religiosity is increasing in the city is wrong. Put simply, this graph seems to show that the number of people who are religious in East Jerusalem is decreasing. Meantime, the proportion of Palestinians in the West Bank self-identifying as “somewhat religious” has stayed relatively constant, if not slightly higher during the same period. However, these figures must be analyzed together with the Arab Barometer data about Palestinians in East Jerusalem and the West Bank self-identifying as “religious,” which demonstrate that the proportion of respondents in East Jerusalem who identify as “religious” in 2010-2021 increased sharply, while the proportion in the West Bank stayed relatively constant, if not decreasing somewhat (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Religious self-identification: “religious” | Source: Arab Barometer, 2009-2022

Taken together, three clear trends emerge. First, the level of religiosity in the comparison group (the West Bank) during the period was relatively constant. Second, the proportion of respondents self-identifying as “somewhat religious” in East Jerusalem declined noticeably during the period. And finally, the proportion of respondents self-identifying as “religious” in East Jerusalem increased significantly during the period. Further, the data suggest that while there were no material changes to religiosity during the period in the West Bank, in East Jerusalem, it may be the case that those who had self-identified as somewhat religious, are now identifying as firmly religious.

The data from the PCPSR survey further underscore the Arab Barometer results. In particular, in both 2010 and 2022, the PCPSR survey asked respondents, “What are the things that you like most about living in East Jerusalem?” In both years, most important to respondents in East Jerusalem was the al-Aqsa Mosque. In 2010, however, 44.8 percent of respondents said it was most important to them, whereas in 2022, that number had increased to 55.3 percent, or a 23.4 percent increase. During the same period, the importance of other holy places to respondents decreased approximately by 68.51 percent (PCPSR, 2022). These trends, taken together, suggest that along with increased individual religiosity in East Jerusalem in 2010-2022, al-Aqsa became more important for residents living there.

Terrorism in Jerusalem

The last question to be addressed is: has there been an increase in terrorist attacks emanating from East Jerusalem? The source of the data is the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which has tracked victims of terror since September 27, 2000, with a particular focus in this paper on 2010-2023, since most of the data on public opinion discussed above come from that period.

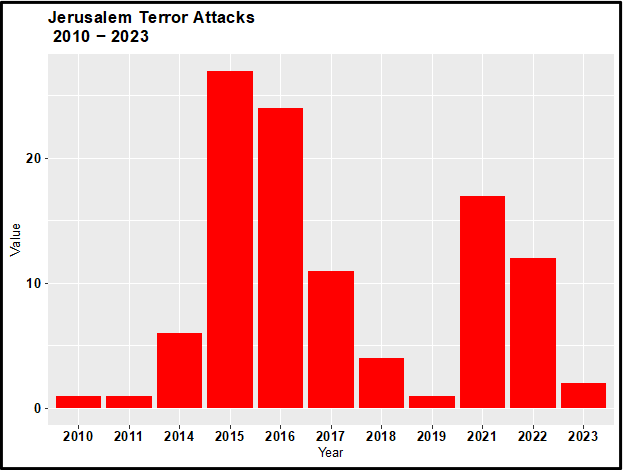

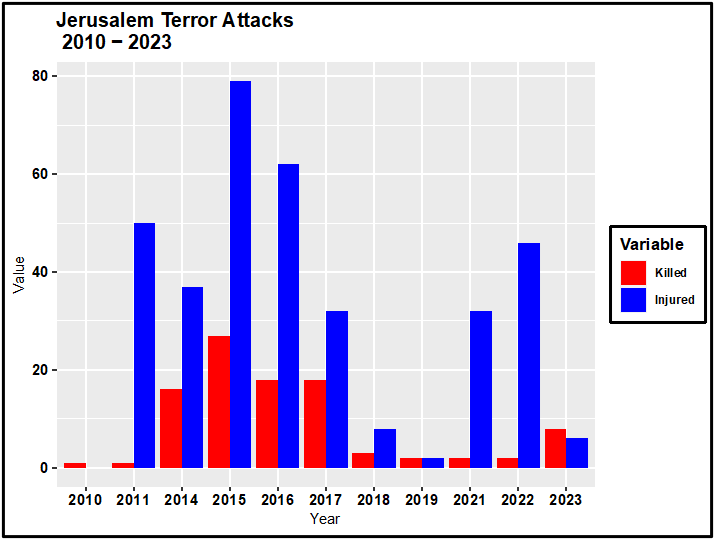

When an attack occurs in the city, the terrorist executing the attack is presumably from Jerusalem and its environs. This assumption is based on the claim made by the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs that most terror attacks concentrated in greater Jerusalem are carried out by “young lone terrorists, most of them from East Jerusalem, and some from Judea and Samaria” (this claim focuses specifically on the wave of terror in 2015-2023) (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2023a). With the research question above and this assumption in mind, I focus on attacks carried out in Jerusalem. Figure 8 presents the total number of attacks carried out in Jerusalem by year, while Figure 9 presents the total number of people injured and killed by terrorist attacks in Jerusalem by year. Years with no attacks in Jerusalem are omitted.

Figure 8: Number of terror attacks in Jerusalem | Source: Johnston, 2023; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2023b

Figure 9: Killed and injured in Jerusalem terror attacks | Source: Johnston, 2023; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2023b

These statistics show that since 2010, there has been an increase in the number of terrorist attacks in Jerusalem. However, that statement masks three trends that emerge from the data. First, there was a spike in terrorist attacks in Jerusalem in 2015-2017 (the “knife intifada”). Second, there was a decrease in terrorist activity in Jerusalem from 2018-2020. And finally, while at the time of this writing the data from 2023 is incomplete, it does appear that there has been a spike of terrorist attacks in Jerusalem from 2021 to the present.

There is one other significant trend in terrorist attacks carried out in Jerusalem since 2000 that is contained in the data but not shown in by Figures 8 or 9: Of the terrorist attacks that occurred in Jerusalem from October 2, 2000 to January 24, 2008, terrorist organizations including Fatah, Fatah’s al-Aqsa Brigade, Hamas, Islamic Jihad, or Tanzim claimed responsibility for 60.71 percent of them. In contrast, after January 24, 2008, the data from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs does not list one terrorist group claiming responsibility for an attack in Jerusalem (“Victims of Palestinian Violence and Terrorism,” 2000; Johnston, 2023). This suggests that currently, “lone-wolf” attacks are by far the most common form of terrorism in Jerusalem—which is corroborated by the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs analysis (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2023b).

In response to the question posed above, Figure 8 and Figure 9 show that there has been an increase in terrorist attacks in Jerusalem over the last thirteen years, albeit with fluctuations within that period. Significantly, compared to the terrorist attacks in Jerusalem in the early to mid 2000s, those carried out in the city today are apparently overwhelmingly individual actors with no formal connection to an organization like Hamas or Islamic Jihad.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This article emerged from a series of in-depth discussions with East Jerusalem Palestinians conducted by the author during the fall of 2022. During the course of those discussions, a common claim emerged, namely, that Israeli policy in East Jerusalem has caused economic underdevelopment and political and social isolation. Stemming from those outcomes and searching for some kind of purpose and effective representation of national identity, East Jerusalem Palestinians have turned to religion, and al-Aqsa in particular. Finally, they argued that this heightened religiosity, taken together with a lack of personal direction, led to more East Jerusalem Palestinians willing to become so-called martyrs, and sacrifice themselves in terror attacks against Israel. In addition, they contended that the key link between religious extremism and terror was Israel’s activity at al-Aqsa. They claimed that al-Aqsa represented the last vestige of any form of national identity—`and one that Israel has yet to take from them. As a result, and in an effort to defend this identity, some of these East Jerusalem Palestinians are willing to turn to violence and terrorism.

My goal in this article was to study these claims more precisely by identifying the specific policies to which these East Jerusalem Palestinians may have been referring, researching the socioeconomic conditions in the Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, examining public opinion data to understand how these policies and conditions have actually affected the residents of East Jerusalem, and checking to see whether there actually has been an increase of Palestinian terror in Jerusalem. In large part, while not establishing a causal connection, the data presented in this paper provide support for the claims of the East Jerusalem Palestinians. In particular, much of Israeli policy in East Jerusalem over the course of the last 20-30 years has actively worked against Palestinian interests there. Socioeconomic conditions are bad; the residents have become more distrustful of the government, more politically apathetic, and more religious, and there has been an increase in terrorist attacks against Israelis in the city. Again, while the relationships I have demonstrated in this paper are not causal, they do demonstrate these broader trends that appear to support the claims of the East Jerusalem Palestinians outlined at the beginning of this paper.

The situation in East Jerusalem, however, is not all bad. Consequently, the data presented in this article invite two specific policies that Israel could implement in East Jerusalem to achieve the dual aim of improving socioeconomic conditions for Palestinians there and in turn, perhaps, reducing terror attacks against Israelis in the city.

The first policy recommendation is for Israel to extend and expand Plan 3790. Not expanding this plan would be a grave policy mistake for Israel for four primary reasons. First, if Israel truly does envision a united Jerusalem as the capital of the state and wants to maintain sovereignty there, it must take responsibility for the city’s entire population. Even more right-wing members of the Israeli government have started to recognize this logic, with one senior official under Prime Minister Netanyahu expressing that “if Israel were serious about Jerusalem, it needed to give people full and equal rights, and that called for allocating resources at all levels and not just making cosmetic efforts to prettify the city, but rather [recognizing] that there was something deeper needed there” (Hasson, 2021). Second, and relatedly, Plan 3790 has improved both the socioeconomic conditions in East Jerusalem and local opinions about municipal services there. This is clear from the tangible improvements, in addition to the PCPSR public opinion data showing that relative to 2010, East Jerusalem Palestinians expressed greater satisfaction with 21 municipal services, in comparison to less satisfaction with just five.

Third, in the sphere of education, Plan 3790 has been what approaches a sea change for the residents of East Jerusalem. Perhaps most importantly, it has extended funding to allow qualified East Jerusalem students to study at Israeli universities, many of whom would otherwise be unable to do so. In addition, the plan dedicated resources to improved instruction of Hebrew in East Jerusalem. These resources were used to improve the quality of the instructors, pedagogical methods, and in turn the students’ educational results. In terms of educational development, 3790 also contributed to improved physical learning environments, such as the well-equipped Alpha School in Beit Hanina. The dedication of these resources to education in East Jerusalem has resulted in tangible gains. Perhaps the most dramatic of these results is that in 2018, there were just 36 East Jerusalem Palestinian students enrolled at HUJI, but as of 2022, there were 710. More East Jerusalem students at HUJI not only increases their engagement with Israelis on an educational level, but they are more likely later to find a higher paying job in West Jerusalem or other parts of the country. The combination of more formal and informal interaction with Israelis, together with the likelihood of greater economic returns from a better education is likely to yield a dampened desire to act violently against these same Israelis or against the system that has provided the opportunity for economic advancement. Indeed (and fourth), the data provide at least some suggestive evidence that this may be the case. In particular, the implementation of Plan 3790 coincided with three years of decreased terrorist attacks in Jerusalem (2018-2020). In sum the decision to not extend and expand Plan 3790 would not only contradict the explicit policy outlined by Israel’s Basic Law establishing a “united Jerusalem [as] the capital of Israel” and “pursu[ing] the development and prosperity of Jerusalem, and the welfare of its inhabitants” (“Basic Law,” 1980), but also possibly incite more terrorism in the city on account of poor socioeconomic conditions and fewer personal educational and economic opportunities.

The second policy recommendation is for Israel to unilaterally extend citizenship to all East Jerusalem Palestinians. First, both PCPSR’s East Jerusalem Survey and the June 2022 survey commissioned by Dr. Pollock make clear that an increasing number of East Jerusalem Palestinians want Israeli citizenship. Second, both the PCPSR survey and the results of a recent qualitative study that included 10 male and 5 female East Jerusalem Palestinians on the psychological effects of accepting (or not accepting) an Israeli passport suggest there are three main reasons for doing so: the economic (employment) benefits; freedom of movement (in Israel, the West Bank, and abroad); and easier maintenance of Jerusalem as one’s center of life (Nager-Abud & Eran, 2023). It would not be a stretch to generalize these three reasons as “belonging and its benefits.” Third, Israeli citizenship would give East Jerusalem Palestinians the opportunity to vote in national elections, and at least some say in selecting the coalition that makes decisions about the municipal services allocated to them. As made explicit by the PCPSR survey, the vast majority of East Jerusalem Palestinians would likely not vote, but again, this decision would at least give them the right to do so, and the ability to oppose governments (like the current one) that work actively against their interests. Finally, in 2019, a record high number of Palestinians received Israeli citizenship (1,200) (“Unprecedented 1,200 East Jerusalem Palestinians,” 2020). Moreover, 2019 and 2020 represented a low point in the number of terrorist attacks in Jerusalem for the period from 2010-2023. To be sure, I am not claiming causality here since other factors—like the implementation of Plan 3790—likely contributed to this dip. There was likely, however, a correlation between the two.

I recognize that this policy recommendation is one that is extremely controversial (Baskin, 2021). More right-wing Israeli Jews in Jerusalem adamantly oppose such a recommendation for three main reasons. First, they fear that the influx of 361,700 Palestinians will dilute the Jewish character of the state. Second, they are fearful of the high birthrate among the Palestinians. And finally, they fear that more Palestinians in Israel would result in more terror attacks. The first two fears are unfounded for three reasons. First, if all 361,700 East Jerusalem Palestinians accepted Israeli citizenship, that percentage of Arabs citizens of Israel would increase from 17.20 to 20.27 percent (Haj-Yahya et al., 2022; Yaniv, Haddad, & Assaf-Shapira, 2022)—in other words, a percentage point increase of 3.07 percentage points. While this is a not insignificant increase, it is also not one that will dilute the Jewish character of the state.

Second, this percentage point increase is based on the assumption that every single East Jerusalem Palestinian would accept Israeli citizenship if it were offered, which is not the case. This stems largely from the social taboo in Palestinian culture of taking Israeli citizenship (even though this taboo has eroded in recent years). Although there is not reliable data on how many East Jerusalem Palestinians would accept Israeli citizenship if offered, one indicative statistic that it would not be all of them is that between 2018-2022, an average of just 1,400 applications for Israeli citizenship were submitted by East Jerusalem Palestinians (Hasson, 2022). Third, while it is true that the Arab birth rate is usually higher than the Jewish birth rate in Israel (Haj-Yahya et al., 2022), those rates have narrowed in recent years, with the fertility rate among Jews even surpassing that of Arabs in 2018 (Aderet, 2019). In any case, an increase of less than 3 percentage points of Arabs in Israel would not significantly impact these trends.

The final fear expressed above, that more Palestinians in Israel would result in more terror attacks, is a fear that is not empirically based and works against one of the main goals of this recommendation. Two fundamental claims of this paper are that East Jerusalem Palestinians are economically despondent and without a firm identity. The East Jerusalem Palestinians with whom I spoke claim that this economic despondency and lack of identity contributes to increased religiosity in East Jerusalem, and in turn, more terror attacks. Again, their logic for linking greater religiosity and commitment to al-Aqsa to terrorism stemmed from their claim that this religiosity and al-Aqsa represent the last remaining fringes of many East Jerusalem Palestinians’ identity. Denied so many other elements of personal as well as national identity, be they economic, academic, or professional, when this remaining pillar of identity is threatened, some East Jerusalem Palestinians are spurred to react violently. Further, East Jerusalem Palestinians explicitly expressed that when they seek Israeli citizenship, they do so for economic reasons and for ways to ensure that they can remain in Jerusalem—which in effect, are two elements of their restored identity, namely, a professional identity that allows them to be economically independent and a locational identity that affords them the opportunity to clearly define a home. As such, by offering East Jerusalem Palestinians citizenship, and in theory dealing with the two core issues in this chain (economic despondency and a lack of identity), the hope would be that subsequent links of terror attacks would be eliminated.

Implementing these two policies faces stiff challenges, especially with the current government. However, the qualitative and quantitative data presented in this paper inform us as to some possible implications of acting without them; namely, more religious extremism and Palestinian terror in Jerusalem. And with regards to the first recommendation, we already have concrete evidence that it will not only improve the quality of life for East Jerusalem Palestinians, but also suggestive evidence that it will decrease terrorism in the city. In the end, these two policies contribute to Israel’s goal of preserving Jerusalem as the unified capital of Israel and minimizing terrorism in the city. The outstanding question is whether Israel has the leaders brave enough to pursue this coherent strategy in the face of what will undoubtedly be political backlash from the more extremist elements of Israeli society. If it does not, the likely result will be an increasingly divided and terrorized Jerusalem.

References

Abu Alhlaweh, Z. (2018, August). The state of education in East Jerusalem: Budgetary discrimination and national identity. Ir Amim. https://tinyurl.com/tzbp65rf

Abu-Lughod, J. L. (1973). The demographic transformation of Palestine. Association of Arab-American University Graduates, May 1973.

Aderet, O. (2019, December 31). For the first time in Israel’s history, Jewish fertility rate surpasses that of Arabs. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/5m8rvkjp

Alayan, S. (2019). Education in East Jerusalem: Occupation, political power, and struggle. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351139564

Al-Haj, M. (2002). Multiculturalism in deeply divided societies: The Israeli case. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 26(2), 169-183. https://tinyurl.com/5en5zxwa

Alian, N. (2016). Education in Jerusalem 2016. Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA). https://tinyurl.com/yyeju6v8

Arab Barometer. (n.d.). https://www.arabbarometer.org/about/

Arab Barometer. (2009-2022). Arab Barometer surveys from Wave II-Wave VII. https://tinyurl.com/23b6k9s8

Asmar, A. (2018). The Arab neighborhoods in East Jerusalem: Kufr Aqab. Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. https://tinyurl.com/3abfn56w

Basic Law: Jerusalem the capital of Israel. (1980. updated through 2022, May 1). Knesset. https://tinyurl.com/yf3shp7r

Baskin, G. (2021, March 17). Israel should give east Jerusalem Palestinians Israeli passports—opinion. Jerusalem Post. https://tinyurl.com/vajcshvz

Benvenisti, M. (1976). Jerusalem: The torn city. University of Minnesota Press.

Cidor, P. (2022, March 24). Meet East Jerusalem’s Arabs going west for education. Jerusalem Post. https://tinyurl.com/2dbruex2

Cohen, H. (2011). The rise and fall of Arab Jerusalem: Palestinian politics and the city since 1967 (1st ed.). Routledge.

Dagoni, N. (2022). Three years since the implementation of Government Decision 3790 for socio-economic investment in East Jerusalem. Ir Amim. https://tinyurl.com/3u64kez9

Dumper, M. (1997). The politics of Jerusalem since 1967. Columbia University Press.

Dumper, M. (2014). Jerusalem unbound: Geography, history, and the future of the Holy City (Illustrated edition). Columbia University Press.

Education Authority. (2022, July 26). Request for data on education in East Jerusalem according to the Freedom of Information Act: Request Number 8529 (2022, July 26). https://tinyurl.com/4v7kmp8j [in Hebrew].

European Union. (2023, May 15). 2022 report on Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem. https://tinyurl.com/ynux9zbz

Habib, I. (2005). A wall in its midst: The separation barrier and its impact on the right to health and on Palestinian hospitals in East Jerusalem. Physicians for Human Rights—Israel.

Haj-Yahya, N. H., Khalaily, M., Rudnitzky, A., & Fargeon, B. (2022, March 17). Statistical report on Arab society in Israel: 2021. Israel Democracy Institute. https://en.idi.org.il/articles/38540

Hasson, N. (2019, November 1). Palestinians are attending Hebrew U in record numbers, changing the face of Jerusalem. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/2wcdc9h2

Hasson, N. (2021, September 9). The unexpected reason Israel is improving conditions for Jerusalem Palestinians. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/44c5xpxz

Hasson, N. (2022, May 29). Just 5 percent of E. Jerusalem Palestinians have received Israeli citizenship since 1967. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/hmsxr5m9

Hasson, N., & Freidson, Y. (2023, May 22). Smotrich halts development plan for Jerusalem’s Palestinian neighborhoods while hiking budgets for settler groups. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/3fwf8d6j

Ir Amim. (2014). Jerusalem Municipality budget analysis for 2013: Share of investment in East Jerusalem. https://tinyurl.com/295pjucz

Ir Amim. (2017). Greater Jerusalem 2017. https://tinyurl.com/3nz45d2h

Ir Amim. (2022). State of education in East Jerusalem 2021-2022. https://tinyurl.com/3w4bzpj5

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (1982-present). Jerusalem database. https://tinyurl.com/my34pac8

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2014). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/mr2mmy8p

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2015). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/nhk4k7vx

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2016). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/fp3sry7w

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2017). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/28jdt4s8

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2018). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/2rfbue6z

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2019a). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/4kfntdy6

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2019b). Mapping East Jerusalem neighborhoods. https://tinyurl.com/4889cntx

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2020). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/29txhd3f

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2021). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/2zvxm99u

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2022). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/2vz8zdpv

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. (2023). Jerusalem statistical yearbook. https://tinyurl.com/y6fb4xzp

Jerusalem Story. (2022, October 22). Three Israeli settlement rings in and around East Jerusalem: Supplanting Palestinian Jerusalem. https://tinyurl.com/2p9r7eh6

Johnston, W. R. (2023, January 29). Summary of terrorist attacks in Israel. https://tinyurl.com/23uaw7tm

Jubran, J., & Barghouthi, M. (2005). Health & segregation 2: The impact of the Israeli separation wall on access to health care services. Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute.

Kark, R., & Oren-Nordheim, M. (2001). Jerusalem and its environs: Quarters, neighborhoods, villages, 1800-1948. Wayne State University Press.

Khader, S. (2021, October 26). Some in East Jerusalem regret neglecting Hebrew, “Language of the Occupier.” Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/mtrzb2w2

Klein, M. (2001). Jerusalem: The contested city. NYU Press.

Koren, D. (2019, January 17). Arab neighborhoods beyond the security fence in Jerusalem. Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security. https://tinyurl.com/38hjky3n

Lee, J. (2023, March 7). 37.9 million Americans are living in poverty, according to the U.S. Census. But the problem could be far worse. CNBC. https://tinyurl.com/57v9xjud

Leichman, A. (2012, September 11, updated). Jerusalem invests millions in Arab schools. Israel21c. https://tinyurl.com/4skswbzz

Library of Congress. (2006). Greater Jerusalem, May 2006. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7504j.ct001915

Lustick, I. (1993). Unsettled states, disputed lands: Britain and Ireland, France and Algeria, Israel and the West Bank-Gaza. Cornell University Press.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2023a, May 18). Wave of terror 2015-2023. https://tinyurl.com/2jran9kh

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2023b, May 30). Victims of Palestinian violence and terrorism since September 2000. https://tinyurl.com/yt9z9wwc

Nager-Abud, M., & Eran, E. (2023). Between identities in East Jerusalem: Palestinian conceptions of permanent residency and accepting Israeli citizenship. Politica, 33, 126-153 [in Hebrew].

Nuseibeh, R. A. (2015). Political Conflict and Exclusion in Jerusalem: The Provision of Education and Social Services (1st ed.). Routledge.

Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR). (2022, November). Special East Jerusalem Poll. https://tinyurl.com/yevb96sw

Peace Now. (n.d.). Jerusalem. https://tinyurl.com/5dbbtavp

Peace Now. (2019). Jerusalem municipal data reveals stark Israeli-Palestinian discrepancy in construction permits in Jerusalem. https://tinyurl.com/mr3z5hca

Pollock, D. (2022, July 8). New poll reveals moderate trend among East Jerusalem Palestinians. Fikra Forum. https://tinyurl.com/mp85k6f9

Romann, M., & Weingrod, A. (2014). Living together separately: Arabs and Jews in contemporary Jerusalem. Princeton University Press.

Said, E. W. (2001). The end of the peace process: Oslo and after. Vintage.

Unprecedented 1,200 East Jerusalem Palestinians got Israeli citizenship in 2019. (2020, January 13). Times of Israel. https://tinyurl.com/3hsedu74

Wasserstein, B. (2008). Divided Jerusalem: The struggle for the Holy City (3rd ed.). Yale University Press.

World Bank (2023a). Poverty Rate by Country 2023. https://tinyurl.com/2ef3tpts

World Bank (2023b). Urban population growth (annual %).

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.GROW

Yaniv, O., Haddad, N., & Assaf-Shapira, Y. (2022). Jerusalem: Facts and trends 2022. Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. https://tinyurl.com/ye27j58e

____________

[1] This claim emerged from research conducted by the author of this article in the fall of 2022. The author conducted 5 in-depth interviews, 25 surveys, and attended one two-day conference at the Legacy Hotel in East Jerusalem from November 1-2, 2022 entitled “Protecting, Preserving, and Investing Waqf Properties in Jerusalem.” Two of the individuals interviewed were also among the 25 surveyed. The interviews and surveys were conducted primarily with small business owners in East Jerusalem, but also included members from the third sector in East Jerusalem, among them the Executive Director of the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA).

[2] The link between these four policies and these two sentiments among East Jerusalem Palestinians is my deduction from these sources, and is not explicitly expressed in these sources.

[3] There is some dispute about the exact number. For example, Peace Now identifies 14 Israeli neighborhoods in East Jerusalem (Jerusalem Peace Now), but others have documented between 8 and 15 (Jerusalem Story, 2022).

[4] Greater Jerusalem advancements of E1 and Har Gilo West are not included in these data.

[5] Urban renewal consists of tearing down the existing buildings and constructing new buildings with a larger number of housing units.

[6] As many as 47,200 during the period 2003-2009 (Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook, 2011).

[7] “The Yearbook is a concentration of data about Jerusalem from a variety of sources, first and foremost among them from the CBS and the Jerusalem Municipality” (Jerusalem Institute, 1982).

[8] For the specific definitions, see the Introduction in the “Employment” section.

[9] Data on hi-tech employment only began in 2017.

[10] The wording of the question in “Appendix 3: Table of Findings” that compares the findings from the 2010 and 2022 polls is as follows: “And what about the mayor of the municipality of Jerusalem Nir Barakat? What do you think his goals are for East Jerusalem for next few years?” (PCPSR, 2022). Presumably PCPSR simply made the mistake of not changing the wording of the question in the Appendix and not in the surveys themselves because as of December 2018, Nir Barkat was no longer the mayor of Jerusalem and in the body of the report on the survey, PCPSR references “the goals of the municipality” and not Mayor Barkat himself.

[11] Such as the quality of teachers in your kids’ school (41.8 percent); Your personal interactions with officials from the Jerusalem municipality (35.6 percent). For a full list, see PCPSR, 2022, Appendix 3, 8:1-8:35.