Strategic Assessment

The article examines the competition over infrastructure as a central pattern of conflict between great powers, and explores how it is being conducted today in and around the Red Sea. It involves a process in which a great power makes major investments in locations that control and threaten a strategically important transport and connection route. The investments are directed at both ensuring the transport and connectivity needs of the great power and its partners and at establishing the ability to threaten those of its enemies. The article begins by laying the theoretical foundation of the various spheres—arrangements and infrastructure—in which the competition is expressed. This is illustrated with a brief survey of the competition in the Indo-Pacific region between China and the United States and their partners. A detailed overview is then provided of the resource-intensive infrastructure competition that is taking place in and around the Red Sea area, with its many participants—Russia, China, the United States, India, the European Union, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey and Qatar — followed by a discussion of the possible consequences for Israeli strategy. The discussion ends with a call to consider various supplementary alternatives to Israel’s policy concerning this competition, including establishing partnerships with countries in the Red Sea area and also with the countries of the “Indo-Pacific arc,” especially with India, which has growing interests in this area.

Keywords: Infrastructure competition, transport routes, ports, Houthis, Red Sea, military bases, great powers, China, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Russia, Iran, Turkey, India, United States, Egypt, Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Jordan

Introduction

For many years, the existence and functioning of global trade routes were taken for granted in most research. In recent years, there have been increasing disruptions in supply chains, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the blocking of the Suez Canal following the Ever Given container ship accident, or pirate attacks. But as evident in the recent article by Yigal Maor and Yuval Eylon (2024), these disruptions were understood as unpredictable “black swan” events, because the reasons for them are diverse and even random. The Houthis’ attacks in the Red Sea, however, which forced a significant portion of global trade to change routes and sail around Africa on a long route between the West and the East, raise the question of whether these are only unexpected episodes, or whether the disruption of transport and connectivity between countries and continents could be a result of calculated measures within geopolitical strategies, which can certainly be foreseen.

During the peak years of globalization, many trade routes were opened and agreements between countries were signed, signaling an era of unprecedented international trade and connectivity. But as will be presented below, it seems that this period is on the wane, and instead of connecting countries, the main trade routes are now becoming a central arena of conflict between them. This arena sometimes flares up, as with the current Houthi attacks, but this is only the tip of the iceberg. This article reveals how great powers invest enormous resources in developing infrastructure that will strengthen their control of the major international trade routes, both to ensure the security of their trade and that of their partners, and in order to establish their ability to threaten their competitors. As will be clarified, this is a characteristic pattern of cold conflict, a strategic process of projecting power that every great power or geopolitical bloc of countries needs to take part in as the polarization between countries and blocs intensifies. This process has the potential to have a very significant impact on Israel, due to its location in the Red Sea area, which it borders, and due to the importance of that Sea for Israel’s own trade and connectivity. This article is the continuation of a current research effort in Israel on the geopolitics of energy infrastructure (e.g. Dekel, 2024) and maritime transport (e.g. Maor and Eylon, 2024), and an examination of how these will affect Israeli geo-strategy.

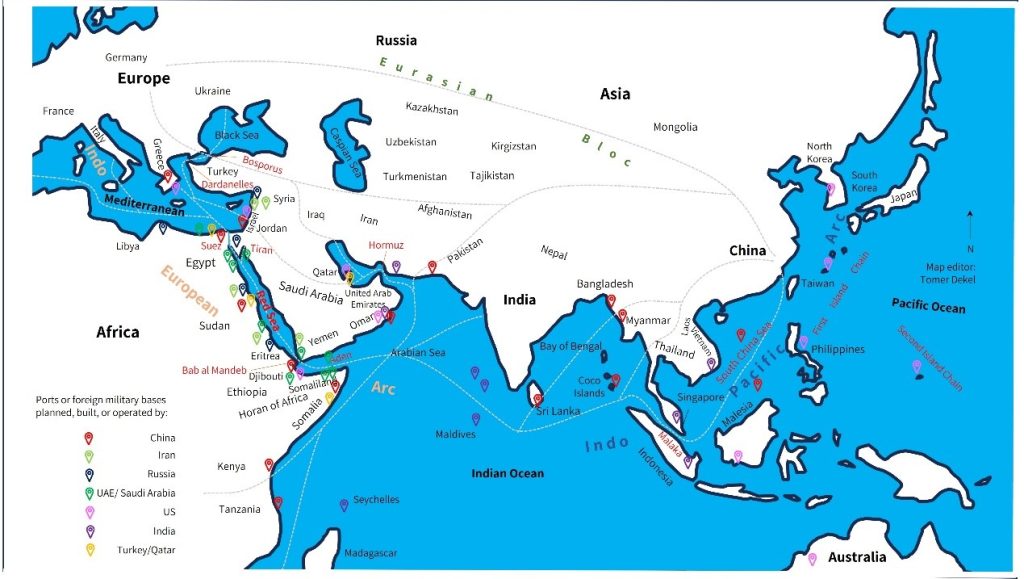

The article opens by laying theoretical foundations for what will be defined as “infrastructure competition” (Leonard, 2021). Afterwards a concise illustration of the theory is provided by describing the competition over infrastructure between China and the emerging Eurasian bloc on the one hand and the United States and the countries of the “Indo-Pacific arc” that surrounds China on the other hand. The third section contains an in-depth overview of the infrastructure competition in the Red Sea between many great powers and countries with diverse interests, from the United States and China to the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, Qatar, the European Union, India, and Russia. In conclusion, possible directions are raised regarding how Israel should approach these developments on its southern front.

The Motivations and Characteristics of Infrastructure Competition

The complete dependence of modern economies on the movement of trade between countries and between continents constitutes a vulnerability and incentivizes their adversaries to threaten their trade routes. A considerable portion of the important trade routes in the world pass through “choke points”—straits in which much traffic must pass through a narrow sea passage that is controlled from all sides—, which leads to clear competition for their control. The blocking of a major transport route causes price increases, limitations on the supply of products, and in certain cases even economic crisis, unless the threatened power is able to find an alternate route that is safe from threats. As a result, great powers engaged in a cold conflict are forced to wage a sophisticated game of chess that combines strengthening and reinforcing the routes they need, projecting power, and containment of the adversary on all sides by tightening the hold on its “lifelines” in order to render them choke points at the moment of truth (Gaens et al., 2023; Leonard, 2021; Schindler et al., 2024).

The reconfiguration of global movement is creating a new kind of regional[1] world order in which major blocs of neighboring countries consolidate independence within themselves, detached from others (Chen, 2023). This regionality is growing stronger, especially due to the increasing tension between the competing blocs led by China and the United States (Schindler et al., 2022, 2024). The blocs are gradually organizing themselves into large regions, albeit in processes full of internal contradictions, and not within absolute boundaries. The most distinct and well-established bloc is the Atlantic bloc—Europe and the United States. Another bloc whose consolidation has been evident in the past decade is the Eurasian bloc, which surrounds China and includes Russia, Iran, and some of the countries of Asia and the Middle East. Finally, in response to the growth of the Eurasian bloc, a new constellation is forming (whose boundaries are the vaguest)—the Indo-Pacific bloc composed of India, Japan, and some of the countries of Southeast Asia, which are increasing their partnerships with the United States (Gaens et al., 2023). The development of the blocs, despite the differences and even tensions among their member countries, stems in many respects from the interest in creating safe trade and connectivity routes in their home territories, which they control, but also vice versa—the deployment of infrastructure networks shapes the blocs around it (Flint & Zhu, 2019).[2]

The geopolitical literature on the intersection between the development of great power infrastructure, trade routes and choke points is not broad, and no comprehensive model has been proposed yet that details the motivations and all of the methods used in the competition between the great powers. For example, the extensive discussion that exists on the topic of the infrastructure that China is developing throughout Asia does not address the practice of cultivating proxy organizations in failed states as a method of threatening a route; and vice versa, the research on proxy organizations dedicates little attention to their role in the infrastructure competition between the great powers. To this end, a model is proposed here based on connecting the phenomena, each of which is illuminated separately in the literature, and it is validated using the case study of the Red Sea.

Of the phenomena described in the literature, the competition can be defined as comprising two spheres—physical infrastructure and arrangements (or alliances)—each of which is composed of several complementary components. The two spheres simultaneously pertain to both strengthening and protecting a great power’s control of a route, and to building up its ability to threaten the competitors’ routes. The first level is the sphere of physical infrastructure and the first component of it is civilian infrastructure. Great powers must constantly expand their investment in developing infrastructure in foreign countries, by financing (investing or providing loans) or establishing it themselves. This comprises investment in transport infrastructure—roads, railroads, pipelines, canals, ports, and so on—but also other infrastructure (for example communications, dams, and power lines) or supplementary projects (training, research, and more), and thus dependence emerges, and cooperation increases with the great power (Harlan & Lu, 2024; Schindler et al., 2024). Moreover, the establishment of infrastructure is often an opening for the great power’s entry—via private or governmental companies—as an operator, maintainer, or partner in them, thus ensuring the deepening of its control of traffic on the route (Kardon, 2022).

Civilian infrastructure can be crucial to establishing an intercontinental route (for example a port or railroad), or alternatively infrastructure that is not directly related to the route (for example, investment in an industrial zone or power plant). Investment in the latter kind may seem like it does not pertain to infrastructure competition, but in fact, in many cases they are closely connected. A great power’s investment in any kind of infrastructure in a certain country both strengthens the relations and the dependence between them and paves the way for the development of necessary infrastructure in the future, so the great powers are in an intensifying race to invest in all areas of civilian infrastructure in countries at strategic locations.

It is important to note that some of the infrastructure established is in fact bypass infrastructure, meaning infrastructure that paves alternative routes that bypass the (potentially) threatened route and ensure the continuity of transport even if the route becomes blockaded. This type of infrastructure includes railroads, pipelines, roads, or cables that are placed on overland routes and pass through friendly countries (Dekel, 2024; Murton & Narins, 2024).

The second component in the sphere of physical infrastructure is military infrastructure. In order to threaten and simultaneously protect a choke point, it is necessary to station defensive and offensive capabilities (for example missile launchers or drones) in positions that grant control of the area; and in order to protect these positions and the route itself from attack by the adversary, it is necessary to station military units that are capable of performing defensive or offensive actions in the threatened area over time. Whether these are naval, air, or land units, a broad deployment of military infrastructure is necessary in the whole region, including ports, bases, logistical facilities, outposts, launchers, communication facilities, electronic warfare, and so on (Becker, 2020; Dasgupta, 2018; Donelli & Cannon, 2023; Dunn, 2023).

The arrangements sphere concerns the nature of relations between the great power and the country at the strategic location, and the first component of it pertains to official or unofficial agreements between them. The establishment of infrastructure, whether civilian or military, depends first of all on agreement and on the arrangement of relations between the establishing country and the country hosting the base or serving as a “transit country” for infrastructure, which in turn affects an especially complicated web of alliances. Small countries see this as a golden opportunity to charge rent and to attract investment and support from the interested great power. Aside from the establishment of infrastructure that will also serve the residents of the country itself, the willingness to establish infrastructure involves exceptional benefits, including supplementary aid and development projects, the provision of loans, trade agreements and the expansion of economic relations with the great power and, of course, arms deals and military alliances that many countries desire (Chen, 2023; Schindler et al., 2022). Agreement to host a base of a foreign power or to allow it to use existing infrastructure brings its defensive capabilities with it. On the other hand, in this kind of deal, the host countries expose themselves to the great risk of taking a position against the adversarial power, which could lead to pressure from it or even denunciation, boycott or military retaliation.

The second component in the arrangements sphere pertains to situations in which the great power has difficulty reaching a sufficient arrangement or alliance. In such situations, the great power could choose a military takeover of choke points (Dunn, 2023), or support rebel groups to this end. When a country refrains from allowing the establishment of the infrastructure of a certain great power, the latter has an increased incentive to meddle in the country’s internal affairs and to support opposition parties or coup attempts that would enable it to have a foothold at the strategic point. Sometimes the great power will expect that a friendlier regime will be established, and sometimes, especially in failed states that have difficulty exercising sovereignty in their territory, proxy organizations will be established that will function as a military force in the indirect service of the great power (Nazir, 2024; Spanier et al., 2021).

In this theoretical model, there is no intention of representing all of the initiatives as if their sole purpose pertains to controlling routes. A great power’s investment in infrastructure could stem from pure economic interests, and alternatively, the role of the infrastructure or arrangement could be to establish influence in the host country not only due to its location that controls the route, but also for other purposes (for example obtaining contracts for mining resources). However, establishing control surrounding choke points is becoming one of the most important elements in current geopolitics and a central motivation for the development of infrastructure by the great powers (Schindler et al., 2024). The next section briefly illustrates how these spheres are applied in the Asiatic and Indo-Pacific regions, as part of the increasing tension between China and the United States and their partners.[3]

Infrastructure Competition in Asia and the Indo-Pacific Arc

To China’s dismay, all of the routes leading to China’s ports, which its economy is dependent on, pass through choke points dominated by countries allied with the United States. The “first island chain” extends eastwards of China, in the direction of the Pacific Ocean, stretching from Japan via Taiwan and the Philippines to Australia. In the south, the Strait of Malacca between Indonesia and Singapore is the main route to the Indian Ocean, where most of its oil and gas comes from (from the Gulf countries) and through which most Chinese goods are shipped to Europe’s markets. This vulnerability is known as the Malacca Dilemma (Lanteigne, 2008), and the solutions provided for it by China, and by the countries threatened by it, are diverse.

China has declared, contrary to international law, that the South China Sea belongs to it. In order to reinforce its demand, it has started to build naval bases on coral reefs, while harassing and chasing away vessels of the countries bordering the sea—Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. Meanwhile, China has invested in military buildup, especially in the navy and in “prevention of entry” capabilities (Tangredi, 2019). The growing threat has prompted Japan to lead a counter-alliance called the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP)—including a broad range of countries from around Asia: from Japan and South Korea at one end, via Southeast Asia and India, to East Africa (Hosoya, 2023; Ranglin Grissler & Vargö, 2021). In order to prevent China from blockading transport routes, the Quad was established—a maritime coalition of four powers, Japan, the United States, India, and Australia—in the framework of which joint naval exercises and maneuvers are conducted in the Indo-Pacific region, along with the AUKUS alliance for military cooperation between the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia (Koga, 2024). These join a network of military infrastructure that the United States has deployed with its partners along the first island chain and the second island chain (another chain of islands that is sparser and further from the continent), which dominate China’s exits to the Pacific Ocean (Tangredi, 2019).

In parallel with these processes, China is advancing the giant infrastructure project known as the Belt and Road Initiative—a network of bypass routes via the interior of the Asian continent towards the Indian Ocean, to the heart of Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. The roads, railroads, and pipelines that China is establishing with enormous investments are, for the first time, connecting underdeveloped countries, especially those without seaports, to the Chinese economy, including Laos, Nepal, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, and Myanmar. The infrastructure connection being established between Russia, a huge energy supplier, and China, a huge energy consumer, creates increasing regional integration between the economies of the superpowers that share the Eurasian region (Khan, 2021; Schindler et al., 2022, 2024). China’s overland routes connect to a series of seaports in and around the Indian Ocean that is called the String of Pearls, which enables the transport of energy and goods around the Strait of Malacca and the stationing of military infrastructure around the entrance to the threatened straits (Mengal & Mirza, 2022).

The implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative, which began in 2013, reveals to the competing powers the magnitude of the threat of infrastructure competition with China, and they have gradually announced competing initiatives. In 2021, the European Union launched the Global Gateway program, which aims to invest 300 billion euros over six years in infrastructure throughout Asia, Africa, and South America (European Commission, 2023). Japan expanded its investments in East Asia and together with India announced their intention to establish the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC) (Schindler et al., 2022; Taniguchi, 2020). India is also investing in naval capabilities to strengthen its control in the Indian Ocean (Dasgupta, 2018), in military alliances, and in building the Necklace of Diamonds ports throughout the “Indo-Pacific arc”, to counter Chinese influence (Mengal & Mirza, 2022). The United States, which is a partner in many of these initiatives, is also working to establish the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), which could connect India to Europe via the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel (Dekel, 2024)—more on this in the next section.

Civilian and military infrastructure along the Indo-European and Indo-Pacific arc (map editor: the author)[4]

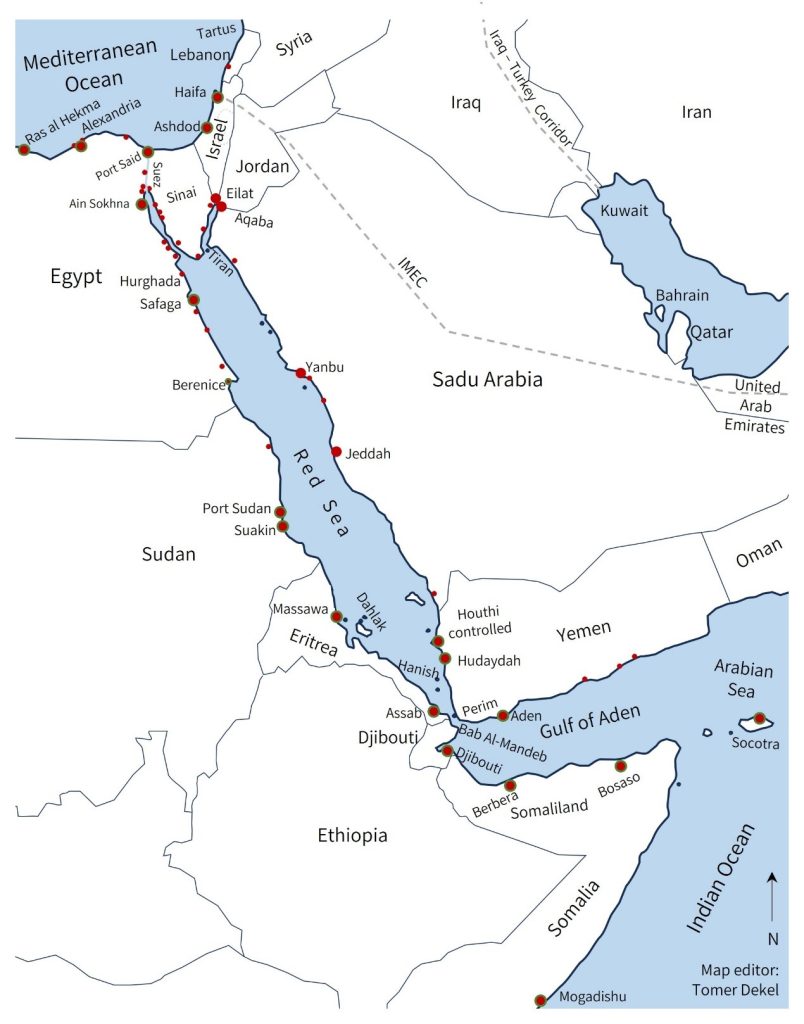

Civilian and military infrastructure in the Red Sea region (map editor: the author)

Infrastructure Competition in and Around the Red Sea

If the Strait of Malacca is the eastern gateway to and from the Indian Ocean, the western gate is the Red Sea, with its two entrances—in the south the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea, and in the north the Suez Canal and the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Like the Strait of Malacca, an enormous volume of global shipping passes through it (for comparison, about 30 percent of global shipping passes through Malacca, while about 15 percent passes through Suez, the next biggest choke point in terms of the volume of shipping; see Notteboom et al., 2022), including oil and gas, food, and other goods, in addition to all of the undersea communications cables between Asia and Europe, and as a result, the great powers are dependent on it to a large extent (Getahun, 2023; Kjellén & Lund, 2022; Lons & Petrini, 2023). The military threat to what can be called the “Indo-Pacific arc,” which leads from the ports of Europe via the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa to the ports of the Gulf countries, India and East Asia, has changed form over the years, from the blockade of the Straits of Tiran in the Six Day War and the closing of the canal after the Yom Kippur War to pirate attacks in the Horn of Africa and the rise of the Houthis in Yemen in 2014. Its great importance has made it an arena of cold conflict and infrastructure competition for many great powers, with each one striving to establish control there for itself, and sometimes also as part of broader alliances. The actions of the great powers in the competition will be reviewed below separately for each great power or group. It is important to note, as the findings will show, that the competition in this area is complicated and does not directly match the inter-bloc competition described in the previous section. Especially striking here is the functioning of regional actors operating in the area relatively independently of the bloc that contains them, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Iran, and also Israel.

Iran

Despite Iran’s geographical distance and economic limitations, which led researchers to define it as a secondary actor in the Red Sea (Marsai & Rózsa, 2023), recent events prove how significant it is there. Since 2011, Iran has invested extensively in long-term consolidation in the “Indo-European arc,” in demonstrating the military presence of its navy, in establishing maritime infrastructure, and in penetrating geopolitically unstable places. The reasons are diverse, but one of the main ones is the establishment of control over the Red Sea, to secure its trade routes and threaten its adversaries. Iran’s support for the rebel faction in Yemen, the Houthis, who have become its proxies, has helped strengthen their ability to choke the Red Sea area. Through them, Iran has succeeded in killing two birds with one stone: striking Israel and the countries of the Sunni camp (especially the Emiratis and the Saudis), which are dependent on the shipping of oil and gas. With Iranian support, training, and backing, as early as a decade ago, the Houthis started attacking Saudi Arabian targets, with which it waged a brutal struggle (Shay, 2018). In 2015, when Houthi forces seized the Yemeni island of Perim, which lies in the middle of the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, Iranian forces deployed on it and their declaration indicated their purpose—for their presence there to “continue forever” (Fargher, 2017)—but the island was conquered shortly afterwards by the Government of Yemen and its allies Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The conflict between them reached a climax in Operation Golden Spear in 2017 (Shay, 2018), but only after October 7, 2023, was there a rise in the quality and volume of attacks at the choke point, when the Houthis started to attack ships that they identified as Israeli (although most were not; only a small portion had an Israeli partner among the owners) (Maor and Eylon, 2024; Pedrozo, 2024).

Like Yemen, Iran also supported and armed Sudan, partly with the expectation of building a port on its coast, and even offered a helicopter carrier in return. The connection with Iran was suspended in the past decade due to Western and Saudi Emirati pressure, but recently one of the generals claiming power in Sudan announced the thawing of relations and the implementation of a large-scale arms deals with Iran (Dabanga, 2024; ADF, 2024; Karr, 2024). In Eritrea, which has been isolated from the West due to its government’s human rights violations, Iran has used the Port of Assab since 2008 to dock its fleet for the purpose of conducting patrols and protecting Iranian ships in the Red Sea. Iran has expressed its ambition to build military bases in Djibouti and Somalia too, but so far this ambition has not been fulfilled (Marsai & Rózsa, 2023). However, since the Houthis’ attacks, the government of Somalia has moved to tighten its relations with the Iranians (which were cut off due to Saudi Emirati pressure in 2016, see below) and spoken out against Israel (Horn Observer, 2024).

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates

The Iranian hold greatly worried its regional adversaries, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, alongside greater fears of instability among their neighbors which overlook their borders and their trade routes. Therefore, in recent years Riyadh and Abu Dhabi increased their investments in all of the countries in the area to the point of direct deposits of billions of dollars for governments, signing defense agreements, mediating peace agreements (for example, between Ethiopia and Eritrea and between Ethiopia and Sudan) and placing a practical demand on these countries to choose sides and distance themselves from Iran, which was indeed achieved for a certain period (in 2016 Somalia and Sudan cut off their diplomatic relations with Iran; Marsai & Rózsa, 2023). Under the leadership of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Council was established, bringing together all of the countries in the area in a defensive alliance (Darwich, 2020; Ding, 2024). Another reason for Saudi Arabia’s great interest in the area is the establishment and expansion of civilian port infrastructure along its eastern coasts, at the Port of Yanbu, Jeddah, or in the futuristic city of Neom (Arab News, 2023).

Each year, Saudi Arabia invests billions of dollars in infrastructure and industries in Egypt (Ahram Online, 2023). Egypt’s economic dependence on Saudi Arabia was expressed in 2016 when el-Sisi, the president of Egypt, agreed to cede sovereignty over the islands of Sanafir and Tiran, which dominate the entrance to the Gulf of Eilat, to Saudi Arabia. This sparked strong public opposition in Egypt, which delayed its implementation for years. The formal transfer finally occurred in 2023 after pressure from the Americans, who saw it as an important step towards advancing normalization between Saudi Arabia and Israel (since Israel’s consent to the deal pertaining to the straits leading to the Port of Eilat was necessary) (Al-Anani, 2023). Moreover, under the influence of the Americans, Saudi Arabia is working to establish a land route that bypasses the Red Sea and also allows Americans forces to use its ports along the Red Sea—issues that will be described below.

The United Arab Emirates operates in the area in relative coordination with Saudi Arabia but also with great independence, and may even be taking the lead.[5] They are currently looking at the establishment of a series of ports and bases under their control, an Emirati version of the String of Pearls (Quilliam, 2022) alongside a series of “flexible military bases” that are established quickly at various sites and abandoned as needs change (Ardemagni, 2024). Egypt receives most of the Emirati investment, which reaches exceptional sums (for example, in 2022 they invested 27 billion dollars in Egypt; EY, 2023), in a wide array of infrastructure and other economic sectors. The United Arab Emirates is acquiring industries in many sectors: It develops or operates the Red Sea ports in the cities of Sharm El Sheikh, Hurghada, Safaga, and Ain Sokhna, and on the Mediterranean coast it is establishing a new port city at Ras el-Hekma (and apparently also a military base) with an enormous investment of 35 billion dollars (Hassan, 2024; Kumar, 2023). It also had a base in Djibouti and for a long period operated ports there, until the government cancelled the contracts, claiming that the Emirati company betrayed its obligations (Donelli, 2022). In Eritrea, the United Arab Emirates leased the Hanish Islands and the Port of Assab (which it recently abandoned, and it is possible that Iran has started to man it in the vacuum that was left) and also established bases on the Yemeni islands of Perim and Socotra at the entrance to the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait (Ding, 2024; Donelli & Cannon, 2023; Getahun, 2023; Sofos, 2023), as well as developing and operating three ports in southern Yemen (Meester & Lanfranchi, 2021).

The countries of the Horn of Africa are a focus of great interest for the United Arab Emirates, which has invested more than 11 billion dollars since the beginning of the twenty-first century in huge civilian infrastructure projects in these countries (for comparison, Saudi Arabia invested only about a third of that sum in those states). In Somaliland, a rebel province in Somalia on the coast of the Gulf of Aden, the United Arab Emirates is building giant ports in the cities of Bosaso and Berbera, investing hundreds of millions of dollars in each of them (Ding, 2024; Getahun, 2023; Sofos, 2023). Their establishment paved the way for the establishment of military ports nearby that rely on them (Quilliam, 2022). By paving a new road from the Port of Berbera to Ethiopia, whose 120 million residents currently lack an effective connection to the sea, the United Arab Emirates aspires to compete with the Chinese corridor (details below) that will connect Ethiopia to the Port of Djibouti (Meester & Lanfranchi, 2021).

It should be added that the Emirati-Saudi drive to establish infrastructural-military dominance in the area is not only part of their struggle with Iran, but also part of their parallel struggle with the Turkish-Qatari axis, which supports the Muslim Brotherhood that threatens them (Donelli & Cannon, 2023; Marsai & Rózsa, 2023)—a conflict that reached a climax a few years ago but has moderated since then. For example, in 2017, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia demanded that Somalia cut of its relations with Qatar, but it refused (other countries in the area, such as Djibouti, did in fact cooperate with this demand). From that point onward, the United Arab Emirates diverted its support from the capital, Mogadishu, to Somaliland. Because of this abandonment, Turkey succeeded in becoming Somalia’s main military supporter, as detailed below (note that recently the United Arab Emirates again announced the establishment of a new base in Somalia; Ardemagni, 2024). In 2022, the United Arab Emirates signed an enormous 4-billion-dollar deal with the government of Sudan to establish a new port north of Port Sudan (Quilliam, 2022). Since the outbreak of the civil war in Sudan, the United Arab Emirates has become the main supporter of one of the factions, in order to refortify its influence in the country (Mahjoub, 2024).

Turkey and Qatar

Turkey has made the establishment of naval power a high strategic priority, as can be seen in the Blue Homeland doctrine that it published in 2006. Another policy document published recently titled, The Century of Türkiye, clarifies that although most of Turkey’s attention is focused on the seas directly around it (the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea), Turkish interests very much involve securing the transport of goods and energy resources from the Indian Ocean (Cubukcuoglu, 2024; Saha & Cannon, 2024). Turkey started to implement this doctrine in 2011 in Somalia, where it chose to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in humanitarian projects, peacekeeping measures, and later in the establishment of a Turkish military base in the capital, Mogadishu (the biggest outside of Turkey) (Sofos, 2023). In 2024, new, broader agreements were signed between the countries for the supply of weapons and training. Turkey started to upgrade the Port of Mogadishu and has been operating it since 2013, and the new agreements between the countries make clear that Turkey will be able to use the port for the purposes of its navy, which it will use to project power towards the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean (Cubukcuoglu, 2024).

Aside from Somalia, Turkey is now investing 7 billion dollars in establishing an industrial zone, logistics and railway infrastructure at the port of Jarjoub in northern Egypt (Port2Port, 2024). Such investments, each in the hundreds of millions of dollars, have increased recently, while attempting to moderate the tension that exists between Turkey and Egypt and simultaneously to render Egypt as Turkey’s “gateway to Africa” (Yehia, 2024). In 2017 in Sudan, Turkey led a large-scale investment campaign in industry, agriculture, water infrastructure, the construction of an airport, and above all, the leasing of the port of Suakin, an ancient Ottoman fortress, in order to build a civilian and military port there. Meanwhile, Turkey’s partner, Qatar, announced the investment of 4 billion dollars in the construction of a port at that site, along with huge investments in roads in Sudan, Eritrea, and Somalia (Ding, 2024; Tekingunduz, 2019). After the coup in Sudan in 2019, the contract was suspended, in part due to Saudi and Emirati pressure. At present Turkey is supporting one of the factions fighting in Sudan, in the hope of reestablishing its foothold in the country (Sofos, 2023; Sudan Tribune, 2024). Turkey is also active in supporting Hamas (though as a marginal actor) and Islamic communities in Israel, in building informal infrastructures in Bedouin settlements (Dekel et al., 2019) and in supporting the (recently triumphant) rebel factions in Syria.

Russia

Russia also has a growing interest in extending its influence along the “Indo-European arc” (Rogozińska & Olech, 2020). The sequence of Russian “strongholds” starts at the Syrian port of Tartus on the Mediterranean coast, which they received after President Bashar al-Assad survived the coup by the skin of his teeth, thanks to their military intervention in the civil war (the recent events in Syria will probably force them to withdraw and enable Turkey to enter the vacuum). The sequence continues in Egypt, which, despite protests from the United States, has been strengthening its ties with Russia for more than a decade with military cooperation, major arms deals, permission for Russian military use of Egyptian bases and ports (Kjellén & Lund, 2022), and the Russian construction of a nuclear power plant, which is based on an investment of 20 billion dollars, in the city of El Dabaa in northeastern Egypt (Tharayil, 2024). In this way Russia is helping Egypt renew and strengthen its military force in an exceptional manner and thus build an especially strong naval force (Henkin, 2018), which is based on military ports at Berenice in the Red Sea, Port Said in the Suez Canal, and Jarjoub in the Mediterranean Sea. It is possible that Russia intends to help Egypt in its struggle against Islamic terrorism in Sinai and thus to gain a complete foothold in the area, similarly to its model of operation in Syria.

South of there, Russia is also establishing arrangements to receive docking permits at ports throughout the Indian Ocean, and is conspicuously holding joint naval exercises with China and Iran in the Arabian Sea (Elmas, 2024; Kjellén & Lund, 2022). In Sudan, Russia is striving to establish an independent base in the city of Port Sudan and has already begun to devise a deal with the government, which led to a clear threat from the United States towards the Sudanese government, leading the government to postpone signing (Satti, 2022). Recently however, against the backdrop of the civil war in the country, one of the generals claiming power in Sudan approved the deal with Russia to establish a logistical and military port at Port Sudan (Dabanga, 2024; Karr, 2024; Knipp 2024). Meanwhile, there appear to be signs that Eritrea will also allow Russia to establish a base in the port city of Massawa (Plaut, 2024).

India

India also has great interest in projecting its power into the Red Sea area, especially as part of the Necklace of Diamonds strategy, whose goal is to compete with China’s growing influence in the region via a chain of ports under its control. After a long period during which India focused on establishing infrastructure in the eastern Indian Ocean extending towards the Strait of Malacca, it declared that it is restoring its emphasis on the western Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Aden. To this end, India is investing a great deal of capital in establishing the Chabahar Port in Iran (Dagan Amos, 2024; Mengal & Mirza, 2022) and in establishing naval bases in the Seychelles, Maldives, and Minicoy Island—all of them surrounding the Arabian Sea and enabling the activity of the Indian Navy in the Red Sea area (Xiaojun, 2024). Oman allocated a logistics complex to the Indian Navy at the Port of Duqm (Chaudhury, 2024), and India is considering additional large-scale investments to develop this port (The Economic Times, 2024) and other ports and industries in the country, which it considers to be of special strategic importance for it in the area (Khan, 2024). With the Houthis’ attacks during the October 7 War, the Indian Navy increased its presence and activity at the entrance to the straits to an unprecedented level, even if it still refrains from officially participating in the Western coalition against the Houthis (Pant & Bommakanti, 2024).

China

The Houthi crisis in the Red Sea was defined by various commentators as an important turning point in the decline of American hegemony vis-à-vis China. Despite China’s economic losses from the harm to maritime trade and although the United States has urged it to participate in the military operation and also to pressure Iran (which China sponsors in many ways) to stop the Houthis (its proxies), China has refrained from acting except for limited measures of military escorts for Chinese ships. The Houthis even declared that they would not harm Chinese or Russian ships (even though a Chinese ship was in fact attacked, which was explained as a misidentification) (Kumon, 2024). The commentator Nathan Levine claims that whether China finally pressures Iran and brings about the cessation of the attacks or whether the threat continues, with shipping under Chinese patronage continuing to be considered safer, China will benefit because it will be portrayed, for the first time, as the great power ensuring freedom of navigation at sea. Thus it will seize this historic role, which is an important pillar of establishing its hegemony, from the United States (Levine, 2024).

China sees the Red Sea area as the direct strategic continuation of the Belt and Road Initiative, which connects Europe and Africa to it. During the past decade, in certain periods China was the biggest source of foreign investment in Africa, although recently its standing has declined again and it is significantly behind the United States, France, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates and also India. In the Red Sea area, China has not yet surpassed the investments coming from Western sources, and in particular compared to the United Arab Emirates (EY, 2023), and it is apparently focused on more strategic specific projects than competition over general investments.[6] China has a naval base in Djibouti (alongside the bases of other countries, see below), which to date is the first base established outside of its territory, and it is expanding it as a central point for control in the Red Sea and towards the Indian Ocean (Becker, 2020). China goes a long way in investing in ports and other infrastructure in the area and in establishing alliances with countries there, to the dismay of the United States. Of the dozens of countries that China is investing in as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, Saudi Arabia has been in the lead recently in the volume of investment in building infrastructure—about 5.6 billion dollars in 2023 alone (Nedopil, 2024). It has additional holdings in the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Somalia, and Sudan, and invested 12 billion dollars in expanding and operating a wharf at the Port of Djibouti and in connecting it to neighboring Ethiopia with the Yaji Railway and oil pipelines, in order to secure its transformation into the “Singapore of the Horn of Africa” (China exploited the opportunity to gain a foothold at the Djibouti ports after the United Arab Emirates was banned from operating them. Donelli, 2022).

China’s navy maintains a routine presence in all of the Red Sea ports, participates in joint operations against pirates in the Gulf of Aden, and is establishing itself as a growing arms supplier for many of the countries in the area (Wuthnow, 2020). It is also working to position itself as a mediator between enemies in the Initiative of Peaceful Development in the Horn of Africa, which it announced in 2022 (Eickhoff & Godehardt, 2022), and also throughout the Middle East, for example between Saudi Arabia and Iran or between the Palestinian factions. In Egypt, China has become a major investor in industrial and logistics projects that support the expansion of the Suez Canal and also in the Ain Sokhna Port south of it, Port Said, and the Port of Alexandria (Getahun, 2023; Meester & Lanfranchi, 2021; Shay, 2023; Zou, 2021).[7]

In Jordan, which China sees as a “gateway to the Levant” for the Belt and Road Initiative, China has committed to investing 7 billion dollars in industry, in commercial centers and a large coal-fired power plant (which has been defined as the largest private Chinese investment outside of China), in railroads, in a new oil pipeline to Iraq, in a Chinese university and more[8] (Marks, 2022). Finally, China has also become an important infrastructure player in Israel—it built the South Port in Ashdod and operates the Bayport in Haifa under a franchise. This led to warnings from American officials, who were concerned about a Chinese foothold that would post a threat to future American use of the port (Ella, 2019; Chaziza, 2022; Kampeas & Staff, 2019; Invest Saudi, 2024; and see criticism of these claims: Lavi and Orion, 2021). In 2019, growing concerns about Chinese involvement in investments in infrastructure and parallel sectors in Israel led to the establishment of a regulatory mechanism to oversee foreign investment (Ella, 2019). The continued deterioration of relations with China is leading sources in Israel to identify other countries that will be able to handle the implementation of major infrastructure tenders “out of a desire to dilute the dependence on China—in light of its hostile attitude towards Israel” (Reuven, 2024).

The United States and the European Union

The United States has an extensive deployment of about 50,000 military personnel (soldiers and contractors) in the area, with sea, air, and land bases in Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia and additional bases in countries close to the straits, including the United Arab Emirates and Qatar in the Persian Gulf, Oman in the Indian Ocean, and Turkey and Greece in the Mediterranean Sea (Denison, 2022; Wallin, 2022).[9] In recent years, it has expanded the flexible posture method in western Saudi Arabia, arranging for American army use of Saudi air and sea ports along the Red Sea. In this way forces can be deployed quickly and pulled back as needed, both to establish control in the straits themselves and as a set of rear bases in the case of war with Iran (Gambrell, 2021). The United States also maintains extensive control of the base of the multinational observer force established to preserve the peace agreements with Egypt in the Sinai Peninsula (Multinational Force & Observers, n.d.).

The focal point where a very large quantity of military infrastructure is concentrated is the tiny country of Djibouti, which is located on the western coast of the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait. The country has become a multinational center for naval bases, including of the United States, Germany, Italy, France, Japan, and as mentioned above, also China (Becker, 2020; Shay, 2023) (note that the United States’ presence is much more prominent than that of other countries—4,000 soldiers are stationed at the American base, 1,400 at the French base, 1,000 at the Chinese base, and only a few dozen at each of the other bases; Masuda, 2023). These bases are used by the countries of the Western coalition in the struggle against pirates, and since 2023 in Operation Prosperity Guardian against the Houthi attacks. This situation has spurred the Americans to expand their involvement in other countries around the straits, which is expressed in a 100-million-dollar agreement to aid in the establishment of bases for the Somali army (U.S. Embassy in Somalia, 2024), and also Congress’ recent decision to deepen cooperation with Somaliland, and in particular the use of the Port of Berbera, which is in its territory. The details of the decision clearly express its goals, which are defined in the near term as to “support United States policy focused on the Red Sea corridor, the Indo-Pacific region, and the Horn of Africa […] defeating the terrorist threat […] the malign influence of the Iranian regime […] counter China’s influence and interests in port facilities in Djibouti, Mombasa (Kenya), Massawa, and Assab (Eritrea)" (U.S. Congress, 2024). Moreover, the United States is involved in extensive aid programs in most countries in the area, for example in 315 million dollars of humanitarian aid that was recently provided to alleviate the hardships of the civil war in Sudan (USAID, 2024).

The European Union, in its attempt to achieve influence in the region (aside from the bases of EU countries in Djibouti), has since the 2000s invested over 17 billion euros in aid and development projects in Horn of Africa countries. In 2021, it defined the area as a “top priority” and in 2023, as part of the Global Gateway project, it worked to implement an extensive infrastructure development package in the Horn of Africa, with a focus on Ethiopia and Somalia (European Commission, 2023). However, Europe’s policy has not yet become clear, and it is far from the achievements of the competing actors (Lanfranchi, 2023)—an issue that has become even more important since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine War in 2022. Because of the war, Europe is looking for alternative sources of energy to reduce the dependence that it has developed on the supply of natural gas from Russia, and to this end it has turned to the Gulf countries. The oil and gas of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are transferred in ships via the choke points in the Red Sea, and these countries were well aware of the threat inherent in this region even before the flare-up in 2023. Note that the Saudis have an oil pipeline to the Port of Yanbu, which bypasses Bab el-Mandeb, but its size is limited and, in any case, transport from it to Europe remains dependent on passing through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, which are threatened by attacks from countries bordering the sea. Thus, the Gulf countries and the Western countries see great strategic significance in establishing a bypass route, in order to create an alternative that would ensure the transport of energy in an emergency: railroads and pipelines that would be laid between the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel, so that natural gas would flow from the Port of Haifa to Europe.

This vision, under the leadership of the United States, which is called the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), started to take shape with the Abraham Accords and was also dependent on the normalization agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia. The harm to these arrangements due to Hamas’ attack on October 7 played well into the hands of the partners in the Eurasian bloc: the Iranians, as the attack harmed an agreement being formed between their adversaries; the Russians, who refortified Europe’s energy dependence on them; and the Chinese also see this as an advantage, as the IMEC economic corridor under American control challenged the parallel routes being established as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (Dekel, 2024). The situation also plays into the hands of Turkey and Iraq, which at the beginning of 2023 announced their intention to establish a “Suez bypass” corridor of railroads and roads from the coast of the Persian Gulf to the Black Sea coast, with the assistance and funding of the United Arab Emirates and Qatar (Blair, 2023).

Conclusion and Discussion: Israel in the Infrastructure Competition

In recent years, the Red Sea area, located at the heart of the “Indo-European arc”—a critical bottleneck that connects the East and West—has become an arena of intensive competition to establish control by various powers, the clearest expression of which is the competition over infrastructure. In this competition, as defined and characterized in the article, each power is investing great resources in order to set up civilian and military infrastructure that enables it to guarantee its ability to use the transport and connectivity route, as well as to establish a military threat to its competitors in such a way that it would be able to close the route at a choke point when it sees fit. The investment in infrastructure is divided into two spheres—the sphere of physical infrastructure, meaning the direct establishment of infrastructure enabling practical control of the route; alongside investment in civilian infrastructure, industries, and military deals in countries at strategic locations, thus establishing in them the second sphere, the sphere of arrangements, which enables forming alliances with them that will lead them to allow the establishment of infrastructure dominating the route, or alternatively to operate or receive the right to use it as needed. In a country that refrains from enabling the establishment of or access to infrastructure, the rejected power turns to supporting rebel factions (in an existing civil war or in causing the country to deteriorate into such a war) in order to receive an arrangement, and through it, support for the necessary infrastructure after the victory of those factions.

Given the special effort by various powers to establish infrastructure, in diverse ways, as revealed in the study, we can say that an infrastructure competition or even an “infrastructure scramble” is developing in and around the Red Sea. We claim that it is becoming one of the key components shaping the politics and economics of the countries along its coasts. The countries that have established or are striving to establish infrastructure in the area include the United States, China, Russia, India, Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the European Union (and additional countries can also be mentioned whose foothold is expressed only or mainly in bases in Djibouti—Germany, Italy, France, and Japan). This trend also challenges the argument of Maor and Eylon (2024), who recently explained that disruptions to the supply chain stem mostly from black swan events, that is, unexpected crises. Given the tremendous effort invested in the Red Sea area, it is clear that this is a systemic strategic process and not a passing episode, and it is likely that at one stage or another, the threat will be carried out.

The first specific implementation is the Houthi attacks on the Red Sea route, which were made possible by Iranian investment in building up the military capabilities of the rebels dominating the choke point. While the intensity of the impact of the Houthis’ “blockade” of Israel has not yet become clear, the infrastructure competition in the area could lead to much more severe developments in the future, with the establishment of Iranian, Russian, Turkish, and Chinese infrastructure (and that of their proxies). The ability of the current coalition led by the United States to fight against them is already insufficient, and there are concerns that a prolonged economic and political war of attrition could erode the United States’ incentive to invest in it. In addition, the continued investment of the Eurasian bloc—whose hostility to Israel is gradually being revealed—in civilian infrastructure in countries such as Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, and more, could pull them towards it.

It is worth mentioning the critical position of Federico Donelli and Brendon Cannon (Donelli & Cannon, 2023), who argue that while the efforts of the United Arab Emirates and Turkey to establish military infrastructure in the Horn of Africa appear to be preparation for conflict, in practice these countries have no ability to maintain an effective military presence over time, and they expect that the efforts will fade. The findings in this study do not contradict the fact that at present the regional powers may be limited in their ability to establish control in the area, but the consistent and significant efforts certainly indicate their long-term intentions and the likelihood that their capabilities will grow during that time. Another question that currently remains open is how a conflict will be expressed in a country in which several powers have an infrastructural foothold (two prominent examples are Djibouti and Egypt, albeit each in a different way). It is possible that the host country will, when the time comes, be forced to choose sides and expel the opposing side (a demand that was indeed made by the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia towards several countries in the area, regarding detaching from Turkey and Qatar), or the opposite—perhaps the dual presence will prevent each side from gaining an advantage, thus actually preventing escalation towards conflict in this area.

A strategic approach by Israel to the threat could be expressed in creating resilience and diversifying the supply sources of goods and energy (Maor and Eylon, 2024), but at the same time, also in fully entering the infrastructure competition. Due to Israel’s limitations as an independent infrastructure player, four complementary alternatives are proposed here for implementing this strategy, which are based on the insights that arose in the article regarding the dynamic of the infrastructure competition:

- Even though the land routes are limited in scope compared to the sea routes, they serve as an important alternative for emergencies. Therefore, additional importance should be placed on the agreements with Saudi Arabia in order to ensure that the infrastructure that it is establishing will serve Israel and not be used by its enemies, and that a central route of trains and energy pipelines will be established from the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia via Israel (before a competing Iraqi-Turkish route is established).

- If Israel were to form international partnerships and recruit major investors, it would be able to significantly expand its involvement in the establishment and operation of major infrastructure in the fields of renewable energy and water in the dry and sun-soaked Red Sea area. Huge projects that provide energy, water, and food security to Jordan, Egypt, or Sudan, which are always on the verge of economic collapse and famine, would increase their dependence on Israel and its leverage over them (see Deutch, 2023).

- Israel could look further east and formulate a strategy regarding “stretching” the “Indo-Pacific arc” up to Israel’s coast, meaning getting the major actors from the East—Japan, Australia, and India—to see the Red Sea in particular and the “Indo-European arc” in general as an area that is important to their interests, and to enlist them in partnerships in infrastructure and military force (it is even possible to imagine Israeli partnership in defensive frameworks such as the Quad). In this respect, India with its growing power could turn out to be a central actor, and strengthening relations with it would consolidate Israel’s security in the Red Sea over time.

- A strong American presence in the Red Sea should be seen as a necessity for recruiting capital and military force to counter the spread and consolidation of China, Russia, Iran, and Turkey into Israel’s “back yard.” Determined Israeli action in the competition over infrastructure could establish the necessary control in the Red Sea area, re-enlist partners, and ensure the ability to prevent or reduce “choking” in the future.

***

Dr. Tomer Dekel is a planner and geographer, and head of the planning and development unit at the OR Movement, which works to develop the Negev and the Galilee. He deals with the strategic planning of cities, functional urban areas, and industrial clusters. Dekel also engages in research on issues of metropolitan development, Bedouin settlement in the Negev, military geography, and infrastructure geography.

Sources

ADF staff (2024, July 30). Iran pours weapons into Sudan in push for naval base. https://tinyurl.com/4tjey6cy

Ahram Online (2023, November 19). Saudi investments in Egypt hit $6.3 bln: Minister. https://tinyurl.com/2ehv9vda

Al-Anani, K. (2023, March 29). Geopolitics of small islands: The stalemate of Tiran and Sanafir’s transfer impacts Egypt-Saudi relations. Arab Center Washington DC. https://tinyurl.com/53894vba

Arab News (2023, June 18). Saudi Ports Authority signs deal to construct integrated bunker station at Yanbu port. https://tinyurl.com/bdp65ryw

Ardemagni, E. (2024, April 30). Flexible outposts: The Emirati approach to military bases abroad. Sada. https://tinyurl.com/2ad5dtsy

Bea (n.d.). U.S. direct investment abroad: Balance of payments and direct investment position data. Graph: Position on a historical-cost basis, financial transactions without current-cost adjustment, and income without current-cost adjustment. https://tinyurl.com/5n7rc3ym

Becker, J. (2020). China maritime report no. 11: Securing China’s lifelines across the Indian Ocean. U.S Naval War College. https://tinyurl.com/js644fmr

Blair, A. (2023. September 20). Turkey moves against Europe with trade corridor alternative to IPEC. Railway Technology. https://tinyurl.com/5n8knwxv

Chaudhury, D.R. (2024, February 8). Amid Red Sea crisis, India gets a specific zone in Duqm Port. The Economic Times. https://tinyurl.com/2xwxz7yv

Chaziza, M. (2022). Israel-China relations in the new era of strategic rivalry and competition between great powers. Strategic Assessment, 25(2), 19-30. https://tinyurl.com/54e8js2e

Chen, X. (2023). Corridorizing regional globalization: The reach and impact of the China-centric rail-led geoeconomic pathways across Europe and Asia. in M. Steger (ed.), Globalization: Past, Present, Future (pp. 145-160). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520395770-011

China Africa Research Initiative (2024). Chinese FDI in Africa data overview. Johns Hopkins University. https://tinyurl.com/2x6f6huz

Cubukcuoglu, S.S. (2024, May 26). Maritime security aspects of Türkiye-Somalia defense cooperation agreement. TRENDS Research and Advisory. https://tinyurl.com/vcwpyfn3

Dabanga (2024, May 29). Sudan general confirms Red Sea base deal with Russia, strengthens ties with Iran. https://tinyurl.com/4j8dzdw8

Dagan Amos, L. (July 10, 2024). The Chabahar port – India’s entry into geopolitical influence. Perspectives Papers 2,291, Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. https://tinyurl.com/3cyw9ap5

Darwich, M. (2020). Saudi-Iranian rivalry from the Gulf to the Horn of Africa: Changing geographies and infrastructures. In Sectarianism and International Relations (pp. 46-42) POMEPS Studies 38; SEPAD https://tinyurl.com/4ebdrrcu

Dasgupta, A. (2018). India’s strategy in the Indian Ocean region: A critical aspect of India’s energy security. Jadavpur Journal of International Relations, 22(1), 39-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973598418757817

Davis, H. (2023, August 2). How Jordan is stuck in billions of dollars in debt to China. The New Arab. https://tinyurl.com/yc5ewwbz

Dekel, T., Meir, A., & Alfasi, N. (2019). Formalizing infrastructures, civic networks, and production of space: Bedouin informal settlements in Be’er-Sheva Metropolis. Land Use Policy, 81, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.09.041

Dekel, T. (2024). Hamas and the new big game. Strategic Assessment, 27(1), 3-15. https://tinyurl.com/3jnm2b2s

Denison, B. (2022, May 12). Bases, logistics, and the problem of temptation in the Middle East. Defense Priorities. https://tinyurl.com/2xk9mery

Deutch, R. (2023). The heart and the arteries: Strategic vision for Israel as a central country, Hashiloach, 33, 105-126. https://tinyurl.com/b4rwdbmf

Ding, L. (2024). The evolving roles of the Gulf states in the Horn of Africa. Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, 18(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/25765949.2024.2340332

Donelli, F. (2022). The Red Sea competition arena: Anatomy of Chinese strategic engagement with Djibouti. Afriche e Orienti, 25(1), 43-59. https://tinyurl.com/35v9juup

Donelli, F., & Cannon, B.J. (2023). Power projection of Middle East states in the Horn of Africa: Linking security burdens with capabilities. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 34(4), 759-779. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2021.1976573

Dunn, E.C. (2023). Warfare and warfarin: Chokepoints, clotting and vascular geopolitics. Ethnos, 88(2), 246-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2020.1764602

Eickhoff, K., & Godehardt, P.N. (2022). China’s Horn of Africa initiative: Fostering or fragmenting peace? Megatrends Africa. Working Paper 1. https://tinyurl.com/bdf2yadn

Ella, D. (November 18, 2019). A regulatory mechanism to oversee foreign investment in Israel: Security ramifications. INSS Insight No. 1229, Institute for National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/3s7dacsa

Elmas, D. S. (February 5, 2024). Amid the Houthis’ attacks in the Red Sea: Iran, Russia, and China will conduct a joint naval exercise. Globes. https://tinyurl.com/2w6683sh

European Commission (2023, December 15). Global gateway: EU and Horn of Africa countries sign Alliance to boost economic development and combat climate change. https://tinyurl.com/tvx2uss2

EY (2023). A pivot to growth. EY Attractiveness Africa. https://tinyurl.com/374r7ub8

Fargher, J. (2017, April 5). ‘This presence will last forever’: An assessment of Iranian naval capabilities in the Red Sea. CIMSEC. https://tinyurl.com/3x78z2hn

Flint, C., & Zhu, C. (2019). The geopolitics of connectivity, cooperation, and hegemonic competition: The Belt and Road Initiative. Geoforum, 99, 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.12.008

Gaens, B., Sinkkonen, V., & Vogt, H. (2023). Connectivity and order: An Analytical Framework. East Asia, 40, 209-228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-023-09401-z

Gambrell, J. (2021, January 26). US exploring new bases in Saudi Arabia amid Iran tensions. Military Times. https://tinyurl.com/477dka2r

Getahun, S. (2023). The new global superpower geo-strategic and geo-economics rivalry in the Red Sea and its implication on peace and security in the Horn of Africa. Jurnal Ekonomi Teknologi dan Bisnis (JETBIS), 2(5), 375-390. https://tinyurl.com/4sxwd97x

Harlan, T., & Lu, J. (2024). The cooperation‐infrastructure nexus: Translating the ‘China Model’ into Laos. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 45(2), 204-224. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjtg.12535

Hassan, M. (2024, March 5). What are the hidden details of the Egypt-UAE Ras Al-Hikma deal? MEMO. https://tinyurl.com/429bs8km

Henkin, Y. (January 7, 2018). The buildup of the Egyptian army. Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security. https://tinyurl.com/2r74v3cc

Horn Observer (2024, July 3). Somalia’s PM to engage with Iranian IRGC in Iraq amid Houthi and Al-Shabaab deal. https://tinyurl.com/2pzke3p4

Hosoya, Y. (2023). Japan’s defense of the liberal international order: The “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy” from Abe to Kishida. In G. Rozman & R. Jones (eds.), Korea policy – Rethinking the liberal international order in Asia amidst Russia's war in Ukraine (pp. 40-55). KEI. https://tinyurl.com/3cn6mnr

Invest Saudi (2024). Saudi Arabia foreign direct investment report. https://tinyurl.com/2d6b6kst

Kampeas, R., & TOI Staff (2019, June 14). US Senate warns Israel against letting China run Haifa port. The Times of Israel. https://tinyurl.com/bdzfntcw

Kardon, I.B. (2022). China’s global maritime access: Alternatives to overseas military bases in the twenty-first century. Security Studies, 31(5), 885-916. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2022.2137429

Karr, L. (2024, May 31). Africa file, May 31, 2024: Russian Red Sea logistics center in Sudan. ISW Press. https://tinyurl.com/4mbprhsd

Khan, F. (2024). The multi-faceted trajectory of the India–Oman strategic partnership. Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses.

Khan, S.A. (2021). Sino-Russian convergence on Eurasian integration: Understanding the long-term engagement. South Asian Studies, 36(1), 7-16. https://tinyurl.com/msvkpxvf

Kjellén, J., & Lund, A. (2022). From Tartous to Tobruk: The return of Russian sea power in the eastern Mediterranean. FOI-R--5239--SE. FOI. https://tinyurl.com/ye4resk5

Knipp, K. (2024, June 16). Russia’s military presence in Sudan boosts Africa strategy. DW. https://tinyurl.com/45wzptra

Koga, K. (2024). Tactical hedging as coalition-building signal: The evolution of Quad and AUKUS in the Indo-Pacific. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/13691481241227840

Kumar, P. (2023, December 28). AD Ports to invest $200m to develop Egypt’s Safaga port. AGBI. https://tinyurl.com/49ccf2f6

Kumon, T. (2024, April 27). Chinese cargo ships poised to gain from Red Sea tensions. Nikkei Asia. https://tinyurl.com/yjcw4m96

Lanfranchi, G. (2023, December 19). The European Union in a crowded Horn of Africa. CRU Policy Brief. Clingendael. https://tinyurl.com/urh8n8sf

Lanteigne, M. (2008). China’s maritime security and the “Malacca Dilemma.” Asian Security, 4(2), 143-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799850802006555

Lavi, G. and Orion, A. (September 2, 2021). The Launch of the Haifa Bayport Terminal: Economic and Security Considerations. INSS Insights No. 1516, Institute for National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/mr8sr6zm

Leonard, M. (2021). The age of unpeace: How connectivity causes conflict. Penguin; Random House.

Levine, N. (2024, February 11). China is winning the battle for the Red Sea; America has retired as world policeman. UnHerd. https://tinyurl.com/2n2xw9fm

Lons, C., & Petrini, B. (2023). The crowded Red Sea. Survival, 65(1), 57-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2023.2172851

Mahjoub, H. (2024, May 24). It’s an open secret: The UAE is fueling Sudan’s war – and there’ll be no peace until we call it out. The Guardian. https://tinyurl.com/5ujnvbd4

Maor, Y. and Eylon, Y. (2024). The disruption of global and national supply chains—aspects and insights. Strategic Assessment, 27(1), 16-31. https://tinyurl.com/5n95f6p3

Marks, J. (2022, August 24). Jordan-China relations: Taking stock of bilateral relations at 45 years. Stimson. https://tinyurl.com/26wfdadx

Marsai, V., & Rózsa, E.N. (2023). The late-comer friend: Iranian interests on the Horn of Africa. Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, 17(4), 356-370. https://doi.org/10.1080/25765949.2023.2300582

Masuda, K. (2023). Competition of foreign military bases and the survival strategies of Djibouti. JICA Ogata Research Institute for Peace and Development. https://tinyurl.com/4krr828f

Meester, J., & Lanfranchi, G. (2021, October 12). Foreign direct influence? Trade and investment on the Red Sea’s African shores. Hinrich Foundation. https://tinyurl.com/3e45zu35

Mengal, J., & Mirza, M.N. (2022). String of pearls & necklace of diamonds: Sino-Indian geo-strategic competition. Asia-Pacific-Annual Research Journal of Far East & Southeast Asia, 40, 21-41. https://doi.org/10.47781/asia-pacific.vol40.Iss0.5862

Multinational Force & Observers. (n.d.). Multinational peacekeepers. https://mfo.org/about-us

Murton, G., & Narins, T. (2024). Corridors, chokepoints and the contradictions of the Belt and Road Initiative. Area Development and Policy, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2024.2311904

Nazir, T. (2024). Terrorist threats to maritime navigation and ports: Risk assessment and prevention strategy. Terrorism Issues, Islamic Military Counter-Terrorism Coalition. https://tinyurl.com/2cy3ahtn

Nedopil, C. (2024, February 5). China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investment report 2023. Green Finance & Development Center. https://tinyurl.com/35r65r76

Notteboom, T., Pallis, A., & Rodrigue, J.P. (2022). Port economics, management and policy. Routledge.

Pant, H.V., & Bommakanti, K. (2024, February 7). Dynamic shift: Indian navy in the Red Sea. ORF. https://tinyurl.com/47zwjhtr

Pedrozo, R.P. (2024). Protecting the free flow of commerce from Houthi attacks off the Arabian Peninsula. International Law Studies, 103, 49-73. https://tinyurl.com/2csa8hn5

Plaut, M. (2024, January 14). Is Putin now acting on plans to build an Eritrean naval base? Martin Plaut. https://tinyurl.com/3rrcs2hf

Port2Port (March 25, 2024). Egypt: A Turkish logistical industrial zone will be established. https://tinyurl.com/ckcknfuy

Quilliam, N. (2022, November 2). UAE and KSA: Growth and influence along Red Sea. Azure. https://tinyurl.com/47984kmx

Ranglin Grissler, J., & Vargö, L. (2021). The BRI vs FOIP: Japan’s countering of China’s global ambitions. Institute for security and development policy. https://tinyurl.com/32bbubth

Reuven, Y. (May 12, 2024). The Race to the bottom: South Korea Is aiming for Israel’s biggest transportation project. TheMarker. https://tinyurl.com/jaa9a8kp

Rogozińska, A., & Olech, A. (2020, December 9). The Russian Federation’s military bases abroad. Institute of New Europe. https://tinyurl.com/yc6pwfj5

Saha, R., & Cannon, J.B. (2024, April 18). Answering big questions about Türkiye in the Indian Ocean. ORF. https://tinyurl.com/2hx24djt

Satti, A.O (2022, September 28). US warns Sudan of consequences if it hosts Russian military base. AA. https://tinyurl.com/yeywr56e

Schindler, S., Alami, I., DiCarlo, J., Jepson, N., Rolf, S., Bayırbağ, M.K., ... Zhao, Y. (2024). The second cold war: US-China competition for centrality in infrastructure, digital, production, and finance networks. Geopolitics, 29(4), 1083-1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2023.2253432

Schindler, S., DiCarlo, J., & Paudel, D. (2022). The new cold war and the rise of the 21st‐century infrastructure state. Transactions of the institute of British geographers, 47(2), 331-346. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12480

Shay, S. (2018). The war over the Bab al Mandab straits and the Red Sea coastline. Institute for Policy and Strategy. https://tinyurl.com/y2dyanas

Shay, S. (2023). China and the Red Sea region. Security Science Journal, 4(2), 70-84. https://tinyurl.com/2uymndhf

Sofos, S. (2023, July 6). Navigating the horn: Turkey’s forays in East Africa. PeaceRep. https://tinyurl.com/ta782dkn

Spanier, B., Shefler, O., & Rettig, E. (2021). UNCLOS and the protection of innocent and transit passage in maritime chokepoints. Maritime Policy & Strategy Research Center, University of Haifa. https://tinyurl.com/4ph99s9u

Statista (2024). Leading sources of foreign direct investment (FDI) into Africa between 2014 and 2018, by investor country. https://tinyurl.com/49f54ce3

Sudan Tribune. (2024, May 6). Erdogan, Burhan discuss bilateral cooperation. https://tinyurl.com/333yk4a6

Tangredi, S.J. (2019). Anti-access strategies in the Pacific: The United States and China. The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters, 49(1), article 3.

https://tinyurl.com/yt9j5yyw

Taniguchi, T. (2020, October 19). Should we forget about the Asia-Africa growth corridor? Lettre du Centre Asie, 87. https://tinyurl.com/2syejkuz

Tekingunduz, A. (2019). The Saudis, Emiratis, and the future of Turkish projects in Sudan. TRT World. https://tinyurl.com/nhchp4xs

Tharayil, R. (2024, January 24). Egypt, Russia launch construction of new unit at El-Dabaa NPP in Egypt. NS Energy. https://tinyurl.com/584xkxzc

The Economic Times (2024, March 4). Duqm port development deal with Adani Group is open: Oman official. https://tinyurl.com/25mfzej4

U.S Congress (2024). S.Amdt.821 to S.2226. https://tinyurl.com/t2aj9tku

U.S. Embassy in Somalia (2024, February 16). United States increases security assistance through construction of SNA bases. https://tinyurl.com/4fdawmfm

USAID (2024, June 14). The United States announces more than $315 million in additional humanitarian assistance for the people of Sudan. Press Release. https://tinyurl.com/bdemb24r

Wallin, M. (2022). US military bases and facilities in the Middle East. American Security Project. https://tinyurl.com/2p8mx4ax

Wuthnow, J. (2020). The PLA beyond Asia: China’s growing military presence in the Red Sea region. Strategic Forum. National Defense University Press. https://tinyurl.com/2m93wpn8

Xiaojun, K.Z. (2024, April 4). New Indian naval base. Risk Intelligence. https://tinyurl.com/2z8bvjwz

Yehia, A. (2024, May 15). We invest in Egypt as a gateway to Africa and the Middle East: Ambassador of Türkiye. Ahram Online. https://tinyurl.com/2n3rc6dd

Zou, Z. (2021). China’s participation in port construction in the Western Indian Ocean region: Dynamics and challenges. Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, 15(4), 489-504. https://doi.org/10.1080/25765949.2021.2018862_

_______________________

[1] Regional in the sense of blocs on the scale of continents, not in the sense of districts or areas within countries.

[2] Schindler et al. claim that the second cold war is defined through competition between the great powers in four parallel fronts: infrastructure, the digital realm, production and finance (Schindler et al., 2024).

[3] Tension that, for many, indicates the rise of a second cold war.

[4] The maps only present the countries, sites, and infrastructure discussed in the article. As a result, the infrastructure in the Red Sea region appears in full detail, but the infrastructure located in the Indo-Pacific arc does not present the full picture in this vast area.

[5] In fact, while the Emiratis have a huge corporation, on a global scale, that specializes in building and managing ports—DP World, which is the flagbearer of their interests in the infrastructure competition—the Saudis do not have a similar company, and they are often dependent on partnership with the Emiratis to this end (Quilliam, 2022).

[6] From 2014 to 2018, China was the biggest investor in the African continent in terms of capital, with 16 percent of the total sources of foreign direct investment inflow (FDI), with the U.S. and France behind it with only 8 percent of FDI inflow in the continent (Statista, 2024). In contrast, in 2022 China’s standing in this area deteriorated and its investments constituted only 3 percent, which is about 2.6 billion dollars per year. For comparison, that year the U.S. invested 6.8 billion dollars, the United Kingdom and France together about 46 billion, India about 22 billion, and the United Arab Emirates topped the list with about 50 billion dollars of investment in Africa (EY, 2023). However, it is important to emphasize several characteristics of the breakdown of investments—while the U.S. and European countries have a broad distribution among various countries and projects throughout the continent, China is the leader in infrastructure projects in the area south of the Sahara and in East Africa. The leading country in the continent in attracting investment is Egypt (by a large margin, especially compared to its neighbors in the Red Sea area), which in 2022 attracted about 107 billion dollars of capital investments (in comparison, the next country is South Africa with only about a quarter of the investment in Egypt). The biggest investor in Egypt that year was the United Arab Emirates, which invested over 27 billion dollars in the country —more than half of its total investment in Africa (EY, 2023). It should be noted that also in other countries there is a gap between Chinese and other investments. The FDI inflow in Saudi Arabia from U.S. sources in 2023 stood at about 2.5 billion dollars, and from Chinese sources at only about 135 million dollars (also ahead of it in the list of investors are Japan, several European countries, India, and more). There is a gap, albeit smaller, in the FDI stock—20 billion dollars from the U.S. and 5 billion from China (Invest Saudi, 2024). On the other hand, in other countries in the Red Sea area, the U.S. does not invest at all for political reasons, while China makes investments, even if not especially large. In comparing the years 2020-2022 in Ethiopia: in 2020 China invested 310 million dollars compared to 30 million dollars that the U.S. invested (also there China had previously invested hundreds of millions of dollars); in Eritrea, China invested between 50 and 150 million dollars, with no U.S. investment; and in Sudan in 2021 China invested almost 100 million dollars, with no U.S. investment (Bea, n.d.; China Africa Research Initiative, 2024). Thus, China’s entry into Africa is significant but the trend has not yet shown stability over time, and in addition, its investments are not widely distributed and consistent, but focused in certain areas and projects, especially in countries where it can establish a foothold.

[7] As mentioned above, the volume of China’s investments in Egypt (the top recipient of foreign investment in all of Africa) is significantly lower than other countries, including the U.S., the United Kingdom, France, India, and in particular the United Arab Emirates.

[8] Although it is claimed against it that it has difficulty fulfilling its promises, and also that Jordan is sinking into a Chinese debt trap that it will not be able to pay. See, Davis, 2023.