Strategic Assessment

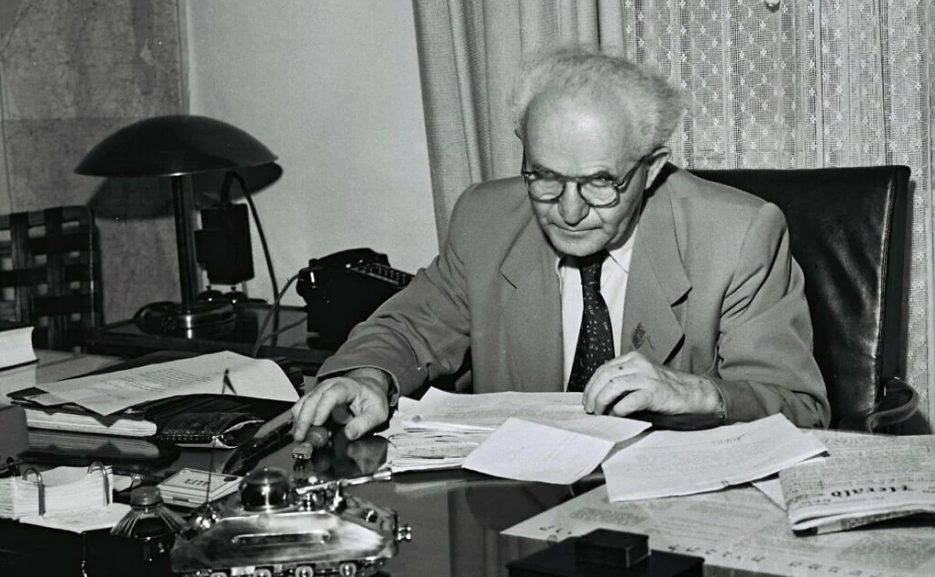

The Image of Ataturk in the Eyes of Ben-Gurion

A few months after he resigned from the government (June 16, 1963), a Turkish newspaper asked David Ben-Gurion to pen an article on the character of Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey. Ben-Gurion wrote an article replete with praise: “Without a doubt,” he wrote, “Mustafa Kemal Ataturk was one of the greatest leaders of the twentieth century prior to World War II and one of the greatest and boldest reformers to emerge in any nation” (Ben-Gurion, 1963).

Ben-Gurion lived and worked as a political figure through one of the stormiest and most fateful periods of the modern era. As a young adult he experienced World War I, and as a major political figure in the Zionist movement he experienced World War II, the Holocaust that was intended to wipe the entire Jewish people off the face of the earth, the first use of nuclear weapons in human history, the establishment of the League of Nations and then the United Nations, and the arrangements that shaped the international system following World War II.

He was well aware of the leadership of many international figures who faced serious crises and overcame them, such as Woodrow Wilson, Lloyd George, Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Konrad Adenauer, Charles de Gaulle, and others. Most of these leaders focused on political and security activity, areas in which they achieved great successes for their nations and for humanity as a whole. Kemal Ataturk, on the other hand, combined bold and balanced military and political leadership with groundbreaking social reformist policy. It was this combination in his personality and leadership that appears to have captivated Ben-Gurion.

To some extent, we can say that, in Ataturk, Ben-Gurion saw his own image and his own type of leadership. He too understood, immediately upon the declaration of Israeli statehood, that without social power, military power could neither be built nor take root. Ben-Gurion was very familiar with the Jewish Yishuv that had been established in Palestine before the Declaration of Independence, and he respected and trusted it. In his view, it was a fighting, pioneering Yishuv—advanced, bold, and with boundless commitment to Eretz Israel.

According to Ben-Gurion, members of the Yishuv had adopted a progressive, Western value system. They were committed to the values of democracy and individual freedom; they aspired to establish in Palestine a state with the most advanced scientific-technological capabilities in the world; they believed that willpower, determination, and perseverance would enable them to meet any challenge that arose—whether socioeconomic or political-defense-oriented in character.

The waves of Jewish immigration (aliyah) that arrived in the country following Israel’s Declaration of Independence, from Eastern Europe and especially from the Arab countries, worried Ben-Gurion. In his mind’s eye, he saw Jews who were still rooted in a Diasporic mentality, and he was very concerned about their ability to meet the difficult challenges they faced in terms of both economics and security. Moreover, practically all of them had come from countries lacking a tradition of democracy, and Ben-Gurion was apprehensive about their possibly negative influence on the democratic character of the state of Israel.

In the security domain, he feared that they would have difficulty holding the land against waves of infiltrators who may try to enter Israel to commit robbery and murder. Indeed, in many instances, leaders of local authorities, development towns, and frontier settlements in which new immigrants—primarily from Arab countries—lived along the country’s borders, made it clear that if the infiltrations continued and the IDF did not provide a suitable response, people would leave their homes and move elsewhere.

To contend with these dangers, Ben-Gurion initiated a system of male and female volunteers, veterans of the Yishuv, who moved to live temporarily in the settlements that were populated by new immigrants. He hoped that in this way the members of the established Yishuv would demonstrate their solidarity with the new immigrants and dissuade them from making good on their threats of abandonment.

In his diaries, his articles, and his speeches, which were too numerous to count, Ben-Gurion describes various aspects of the social and ethical reforms that Ataturk brought to Turkey. Ben-Gurion relates that he was a university student in Istanbul two years before the outbreak of World War I and knew Ottoman Turkey well, including that of Abdul Hamid II and that of the Young Turks. In the 1930s, he writes, he went back to Istanbul to visit and “was almost unable to recognize the people” (Ben-Gurion, 1963).

He also writes that during his studies at the University of Constantinople, no women set foot in the institution, but that the situation changed in the 1930s. During his last visit, he noted that the university was full of male and female students. During his years of study at the university, the women would cover their faces with a veil, as is customary in Islam, but some years later they walked around with their faces uncovered, like the men. The language had also changed; it was no longer based on the Arabic alphabet, as it had been previously (Ben-Gurion, 1963).

For more than a century, Ben-Gurion, writes, Turkey was known as “the sick man on the Bosphorus”—no country wanted ties with it, and everyone talked about its division into sub-states. Under Ataturk’s leadership, Turkey transformed its status. After repelling the Greek invasion, it appeared as a “young man at full strength, and instead of being surrounded by the hatred of its neighbors, both near and far, the new Turkey was the friend and ally of all its neighbors” (Ben-Gurion, 1963).

Ataturk’s strategic achievements gave expression to Ben-Gurion’s realistic worldview, which rested on the assumption that relationships in the international arena are shaped by interests and power. During his tenure as prime minister, Ben-Gurion saw the validity of this worldview expressed in many contexts. This article focuses on two examples.

The first pertains to the decision to declare the State of Israel on May 15, 1948. The decision was made with the knowledge that the balance of power gave clear superiority to the Arab side. A Jewish Yishuv numbering 600,000 people would have to contend with at least some of the Arab countries, with a combined population of tens of millions. The Yishuv’s situation in terms of military equipment was also inferior to that of the Arabs.

At the same time, at the diplomatic level, this decision was clearly at odds with the position of the American administration, and unequivocal threats of an embargo and the denial of economic aid hung in the air. Moreover, Ben-Gurion and the rest of the Israeli leadership clearly understood that an Israeli loss in the campaign would not resemble a “normal” military defeat, in which the winners take control of the conquered area but leave the population in place.

In the Israeli-Arab case, no one doubted that the Arab enemy would seek to destroy the Yishuv in its entirety—women, men, and children. This was at a time when the memory of the Holocaust. which had occurred primarily in Europe just a few years earlier, was still fresh in the Israeli national memory.

Above all, the decision was actually made at a time when the military echelon, led by acting IDF Chief of Staff Yigal Yadin, had reservations, even objected to the move, and explicitly stated that Israel’s victory in the perilous campaign gradually gaining momentum against it was not at all certain. All members of the leadership realized that Ben-Gurion himself and many of his colleagues had no real military knowledge that could enable them to present a position contradicting that of the Chief of Staff.

This was the situation that faced Ben-Gurion on the eve of the decision to declare statehood. It is important to note that the decision was not necessarily a move in a zero sum game—to exist or to cease existing. His partners in both the leadership and the military echelon proposed suspending the decision for a few months and offered convincing reasons, but Ben-Gurion refused. He believed that the target date for the declaration was “a golden opportunity,” that must be seized at once, fearing that otherwise it would never happen. In retrospect, Ben-Gurion’s decision was proven correct. The Jewish Yishuv went to war and paid a heavy price, with almost 6,000 dead, but emerged the victor.

The second example pertains to the Sinai Campaign (October 1956). As we know, the Sinai campaign was launched in cooperation with two colonial superpowers—Britain and France—and was conducted against a developing Third World nation: Egypt. Some feared that this cooperation would result in a rupture between the countries of Africa and Asia, which were starting to develop the International Organization for Non-Aligned Countries under the leadership of Egypt (Nasser), India (Nehru), and Yugoslavia (Tito). They recalled the severe anti-Israel resolutions that were passed by the Bandung Conference of Asian and African states of 1953 in Indonesia. They feared that now there would be even harsher resolutions against Israel, but in practice all their fears proved to be unfounded. Among the countries of Asia and Africa, it turned out, admiration of Israel increased following its victory over Egypt, and the Sinai Campaign was followed by closer relations between the nations of Asia and the State of Israel.

Ben-Gurion acted similarly with respect to other strategic issues that were on the agenda during his years in office, including the decision to move the government’s offices to Jerusalem in response to the U.N. Security Council resolution regarding the internationalization of Jerusalem in December 1949, and Israel’s development of a nuclear option.

In his article in the Turkish newspaper, Ben-Gurion continued:

It is hard to find in recent centuries even one country that has experienced within a short time such far-reaching changes to its culture, society, internal structure, and international standing as occurred in Turkey. The instigator of this renewal and fortifying change, examples of which are few and far between in the history of nations, was Mustafa Kemal [known by the name of] Ataturk. He was a brilliant soldier, a courageous statesman with long-term vision, and a leader who was both daring and cautious, undeterred by any difficulty in the cause of liberating and advancing his people, and who was never intoxicated by his successes or his victories (Ben-Gurion, 1963).

Ben-Gurion went even further, defining Ataturk as:

…a mighty fighter known for eradicating the enemies seeking to terminate the independence and the unity of his homeland, and for his ability to turn yesterday’s hater into a friend and ally, without seeking revenge or brooding over injuries from the past. He was a loyal patriot who was not afraid to stand alone against the entire world; he was able to raise his divided and oppressed nation that had been let down by its failed leaders to the highest levels of unity, liberty, and faith in its own strength. A lone ruler, whose leadership was based on the trust and commitment of the people to democracy and liberty—that was Ataturk, who renewed the youth of the Turkish people, secured its independence and unity, saved it from the decayed legacy of the Middle Ages, and marked out a safe and reliable road for its internal and external advancement (Ben-Gurion, 1963).

Indeed, commentators who examined Ataturk’s revolution also focused on the rare combination of military and social leadership that were clearly reflected in his leadership. In this context, David Siton wrote the following in the newspaper Haboker:

The revolution instigated by Ataturk […] was, first and foremost, intended to liberate Anatolia from the burden of foreign occupation. Thanks to the strong national spirit beating in the hearts of the Turkish people, even during the country’s most difficult days, when it was divided and torn, Mustafa Kemal managed to expel from its borders all the foreign occupiers who plotted to fragment the state and divide it amongst themselves (Siton, 1950, p. 3).

However, Siton continues, Ataturk did not regard the expulsion of foreigners as the summit of his aspirations. He sought to instigate a fundamental revolution in the life of the Turkish nation in order to heal and strengthen it, so that it could become a normal nation. As a first step, he terminated the Caliphate regime in his country. He expelled the Sultan from Istanbul and separated religion from state, and in doing so, he neutralized the influence of the fanatical religious leaders who were the progenitors of the corrupt Ottoman regime. Ataturk’s revolution also encompassed social aspects, including women’s liberation from the shackles of Muslim extremism, purging the language of Arabic foundations, instituting economic processes already established in Europe, and opening the gates to European culture. “All this,” he concluded, “healed the Turkish nation and introduced a new spirit to the country” (Siton, 1950, p. 3).

Turkey’s political, military, and economic power; its close ties to the West, especially the United States; alongside its democratic character, turned relations with Turkey into a strategic asset for the State of Israel in the 1950s. Against the background of the rise of Arab nationalism under the leadership of Egypt’s President Nasser, and the policy of isolation and boycott which the Arab states implemented against Israel, Ben-Gurion initiated the Alliance of the Periphery, which included Turkey, Morocco, Ethiopia, and Iran, among others.

Turkey was the first Muslim country to recognize Israel de-facto in March 1949. Even prior to that, it enabled Jews to emigrate from Turkey to the State of Israel, although it knew that doing so could harm its relations with the Arab countries. Later, Turkey allowed the opening of an Israeli consulate in the country and the appointment of a Turkish envoy to Israel. Israel’s victory over the Arab countries was a central component of the closer relations between the two countries (Lerman, 1950; Podeh, 2022, p. 296).

Ben-Gurion’s Fear of the Rise of an “Arab Ataturk”

For Ben-Gurion, his admiration of Ataturk’s leadership was deeply significant in the context of the Israeli-Arab conflict. To understand this context, we must return to the period following Israel’s War of Independence and the challenges it posed to Israeli decision makers, led by Ben-Gurion.

Just a few months after the end of the War of Independence, Ben-Gurion found himself in a minority position compared to other members of the leadership and a large majority of the public. Everywhere he looked, he saw sentiments of satisfaction, joy, and pride at the great victory. All of this, of course, co-existed with great pain at the heavy cost paid by the Yishuv to achieve that victory. Ben-Gurion shared in this sense of satisfaction but was also cautious in his optimism.

It was, without a doubt, an “absolute victory.” At the end of the war, the IDF controlled an area 25% larger than what had been allocated to the Jewish state as part of the partition plan approved by the United Nations General Assembly on November 29, 1947. Moreover, by the end of the war, it emerged that 700,000 Arabs had left the country and become refugees in the neighboring Arab countries, thereby allowing the Jewish Yishuv to achieve its dream of establishing a Jewish democratic state with a solid Jewish majority.

At the end of the war, the armies of Israel and the Arab countries were exhausted, but the IDF was in a position to continue fighting and seize control of additional territory. A plan for continuation of the fighting was presented to the state leadership for a decision, with the aim of conquering the area of the Old City of Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Hebron. The plan was ultimately not implemented. As it concerned the question of seizing land that was defined as “ancestral inheritance,” serious disagreement arose within the state leadership over the question of who was responsible for the failure to implement the plan. Ben-Gurion, as we know, attached to this ‘failure’ the words “bekhiya l'dorot” (to be lamented for generations), and accused his political rival Moshe Sharett of bearing responsibility (Moshe Sharett & His Legacy, undated).

In any event, the fact that the state leadership regarded continuation of the war and seizure of additional land as a possibility indicates that, at the end of the war, the position of the Arabs was vastly inferior to that of the IDF. The Arabs for their part were well aware of the IDF’s superiority and that it was advisable for them to reach a ceasefire as soon as possible.

Ben-Gurion shared in the joy of the victory, but he also had concerns. He feared it would lead the Yishuv and its leadership to be smug and excessively confident in the IDF’s ability. The assessment that was common in many state leadership circles was based on an ostensibly logical assumption: if a small Yishuv with few and limited resources managed to defeat the seven Arab countries that attacked Israel, then we can look to the future with a great deal of security.

Many members and leaders of the Yishuv believed that the passage of time was working in Israel’s favor. Over time, there would be massive Jewish immigration to Israel, helping increase the strength of the IDF. The conclusion of the war and the signing of the armistice agreements would almost certainly lead the Western powers to lift, at least partially, the arms embargo against Israel. And most importantly, the defeat of the Arab countries would deter them from thoughts of a war that would certainly end in another Arab defeat.

Ben-Gurion feared this way of thinking. In his eyes, such complacency

among the authorities charged with responsibility for state security, posed a genuine risk. He was determined to combat this phenomenon, and to this end he constructed a series of arguments to contend with the danger he saw before him. War, Ben-Gurion maintained, is a phenomenon that is inherent to human history. In other words, human history is in effect an ongoing story of wars with pauses between them. This statement is universal in character, but is particularly applicable to the Israeli-Arab context:

[You believe in] the end of the war. He conducts a kind of virtual dialogue with those who believe in peace. [You know well that] “even if the war ends now [formally], and [even] if [a] peace [treaty] is signed, [the phenomenon of war will continue. The proof is simple]: Has there ever been a war that was not preceded by peace?” (Ben-Gurion, 1948)

The armistice agreements, Ben-Gurion explained to the public, do not ensure peace: “And if someone were to ask me whether there will be war six months from now, I would not say: No” (Knesset Records, 1949, p. 305). He added that the current period “is only a pause [in the fighting] between us and the Arab countries” (Ben-Gurion, 1949a).

This historical assertion, Ben-Gurion believed, applied to human society, and even more so to Israel’s relations with the Arab world after the War of Independence. He was skeptical about the rather arrogant assessment, adopted by many in the Yishuv, that the outcome of the war would lead the Arab countries to abandon the path of war and choose the path of peace. In his eyes, this approach reflected Western thinking, and in one of his speeches, he said:

It cannot be assumed that the failure [of the Arabs in the War of Independence] will deter them from their desire to uproot us from our land. They believe, and this belief is not wholly unfounded, that time is on their side and there is no reason to hurry. They have a lot of time. They have an instructive example from this very land—the Crusader conquest in the eleventh century. A Christian state was established and existed for decades, but the Muslim world ultimately overcame it and uprooted it (Ben-Gurion, 1955).

For many years, Ben-Gurion insisted on the need to see reality not from the perspective of Western nations, but rather from the perspective of the Arab nations. What we regard as rational and guaranteed, he emphasized again and again, does not necessarily appear to be so in the Arab world. They have other codes of behavior, based largely on the concepts of revenge and the defense of honor: “The Arab nations were beaten by us. Will they forget it quickly? Six hundred thousand defeated thirty million. Will they forget the insult? We must assume that they have a sense of honor […] Can we be confident that they will not seek to take revenge against us?” (Ben-Gurion, 1948).

Moreover, Ben-Gurion refused to accept the sense of self-satisfaction that was developing in the Yishuv, together with the admiration for the IDF and its conduct of the War of Independence. He believed that the main reason for the victory in the war was the severe divisions that characterized the Arab world at the time, particularly between Egypt and Jordan, and the corrupt nature of the Arab regimes during the years in question: “We were victorious not because our army performs miracles, but rather because the Arab army is rotten. Must this rot last forever? Would it be impossible for an Arab Mustafa Kemal to arise?” (Ben-Gurion, 1948).

Indeed, Ben-Gurion was gripped by what could be referred to as an obsessive fear, based on the widespread sentiments of self-confidence after the war. He was extremely critical of those who underestimated the Arabs and viewed them as backward people who would never be able to contend with the human quality of IDF soldiers, with their scientific and technological abilities, and especially with the degree of motivation and readiness for sacrifice pulsing within them: “Our neighbors,” he wrote to Chief of Staff Yadin in October 1949, “who we can assume will be better prepared and more unified […] We must raise a fighting nation and train every man and woman, every youth and elderly person, to defend themselves in the hour of need” (Ben-Gurion, 1949c).

Ben-Gurion feared the emergence of a charismatic Arab leader who could unify the Arab peoples against Israel. This phenomenon, he noted, had already occurred in the Arab world in the distant past. Muhammad appeared suddenly in the seventh century, and through the power of his charismatic personality and the tidings of the new religious faith he carried with him, “almost overnight turned the unknown, helpless, and divided Arab tribes into a unified force, a conqueror which since then has changed the face of much of the world and achieved for Arab culture conquests unlike almost any other in all of human history” (Ben-Gurion, 1951).

And of course, the major example behind many of his statements was that of Kemal Ataturk:

I was a student in Turkey before World War I, and I knew the failed Turkish regime well…I thought it was a corrupt and hopeless state…And then all of a sudden…a new spirit arose in the people; a man appeared whose name they did not know…and breathed a new soul into the Turkish nation, rose up against the subjugation imposed upon it by the victors, and defeated the Greeks…It expelled the entire Greek population from Asia Minor, where they had lived for thousands of years…And the Turks, who had been humiliated and oppressed… took courage and became an independent, proud, and respected nation (Ben-Gurion, 1949b).

Such concerns were also common in various circles within Israel. In December 1952, an expert on the Arab world wrote:

From many perspectives, Turkey serves as an example for regimes in the Arab lands. In Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, the army is currently openly controlling the country; …and in Jordan, the Legion are the real power behind the scenes. General Naguib advocates far-reaching reforms…[the rulers of Syria and Iraq] are also interested, ostensibly, in establishing Kemalist regimes (Hiram, 1952, p. 2).

A short time after Gamal Abdul Nasser seized power in Egypt in the Free Officers’ Coup, Ben-Gurion began to recognize that Nasser was a leader on the scale of Ataturk. He estimated that, because of his vision and his immense charisma, he had the ability to unify the Arab countries under his leadership. Were this to happen, Ben-Gurion worried, the existence of the State of Israel would be in real danger. In one of his speeches after the Sinai Campaign, he acknowledged that:

I was very concerned that such a man [like Ataturk] could also arise among the Arab nations. And such a man has emerged, and, at the moment, there is a personal focus for the national aspirations of the Arab nations; it is Gamal Abdul Nasser…he has become the expectation, the bearer of hope for the unity and empowerment of the Arab nations. And one of his goals, albeit not the only one, is the destruction of the State of Israel (Ben-Gurion, 1958).

Summation and Conclusions

The discussion surrounding Ataturk’s personality and leadership, and the danger of such a leader rising to power in the Arab world, reflects the diverse layers of David Ben-Gurion’s leadership and its significance to this day.

Ben-Gurion’s personality combined two ostensibly contradictory characteristics: on the one hand, he was a courageous leader, who sometimes appeared to many to be moving in an almost foolhardy direction, far beyond Israel’s capabilities; on the other hand, his personality also included a deep recognition of the limitations of the power of the Israeli state and major concerns over moves that could drag the country into a military confrontation.

His statements regarding Ataturk unequivocally reveal this duality in Ben-Gurion’s personality and his political worldview. They express his belief that every nation holds within itself immense powers. Wise and prescient leadership is measured, among other things, by how far it understands these forces and can use them to advance the interests of the state. This perception also encompasses the belief that even when nations are at a low point, like Turkey prior to the establishment of Ataturk’s leadership, they must not fall into an abyss of despair. Wise, effective leadership can extract them from their difficulties and raise their status, just as Ataturk had done.

At the same time, Ben-Gurion’s statements regarding Ataturk’s personality and leadership gave expression to the cautious, and perhaps even fearful aspects of Ben-Gurion’s personality and leadership. He lived through the difficult days of the declaration of statehood and the war against the Arab countries completely devoid of any illusion that it was possible to reach a peace treaty with the Arab world. Nevertheless, the vast archive he left behind reveals extensive documentation of his contacts with Arab leaders, for the purpose of establishing peace and calm in Israel. Ben-Gurion says that he presented them with a formula for an agreement that would benefit both them and the State of Israel. Cooperation between the two peoples—with Israel contributing technological knowledge and scientific advancement, and the Arab world bringing natural resources and manpower—would lead to prosperity in the region for both nations. How great was his disappointment when figures who were considered moderate in the Arab world, most significantly Musa al-Alami, rejected his proposals out of hand:

Like all Zionists, I too once believed in the theory that our work would bring blessings to the Arab nations…Then I was naïve to think that the Arabs thought as we do…and I spoke with Arab leaders in Israel and in all the neighboring countries…[However,] when I spoke with one Arab, an educated and honest man [Musa al-Alami], about the blessing that our presence brings them, he said to me: That is true, but we do not want this blessing. We choose for the land to remain poor, meagre, and empty, until we learn to do what you do. If it takes another 100 years, we will wait another 100 years (Knesset Records, 1960).

Against this background, during all his years in office Ben-Gurion made sure to caution security personnel against complacency, smugness, excessive self-confidence, downplaying the capabilities of the enemy, and the unbridled buildup of our military capabilities. It was Ben-Gurion who, from every podium, warned that the Czech-Egyptian arms deal endangered the very existence of the State of Israel. It was he who changed the conception of the activity of the German scientists in Egypt at the beginning of the 1960s and understood it as a serious threat against Israel, while many within the Israeli security establishment tended to belittle its severity.

At the end of the Six Day War and the great military victory that resulted, the response by the Israeli leadership was a far cry from Ben-Gurion’s cautious approach. Prime Minister and Defense Minister Levi Eshkol was unable to restrain the immense euphoria that erupted instantly, once it became clear that the IDF had succeeded in defeating three Arab countries—Egypt, Syria, and Jordan—and had seized control of vast territories: the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights.

After the war, Major General Ezer Weizman, then Chief of Operations on the General Staff, said:

I think that the Arabs have many good qualities of their own…However, their fitness for war is a different matter…The time has come for them to understand that war is not for them…Even today you can see Jews here and there who are beset by a fear of gentiles. We must stop being afraid of gentiles once and for all and start understanding that the world fears us more, because it recognizes our greatness much more than we do (Ya’alon, 2017, pp. 97-98).

Major General Yehoshafat Harkabi went further, stating:

War is a social act. The ability of a nation to fight depends largely on the ability of its citizens to work together. The Egyptian nation is not a [unified] organism, but rather a mass of individuals acting as individuals according to their own personal interests, and not as a group, according to collective ideas. They are therefore unable to [conduct] an effective war (Shalom, 2023, p. 96).

Elsewhere, he spoke similarly:

In Arab society, there is almost no unity. Each person acts for himself and feels alienated from others…In the IDF, each soldier is confident [that if he is injured], his comrades will not leave him on the battlefield. The Egyptian soldier is convinced that his comrades will abandon him. The result is that an IDF unit reacts to fire in a unified manner, and the Egyptian unit reacts by crumbling…War demands group action (Shalom, 2023, pp. 96-97).

The smugness of the political and military leadership in Israel continued in subsequent years, right up to the present. It led Israel’s security establishment to maintain the fixed mindset that “Hamas has been deterred” (Zitun and Halabi, 2023). This assessment constituted the basis for the complacency that preceded Hamas’ attack on October 7, 2023. This sense of self-confidence was also present on Israel’s northern border and is what led to the policy of containment in the face of Hezbollah’s immense accumulation of strength, which seriously endangered the State of Israel, and to the belief implied by former Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon, that there was no reason to worry, as “the rockets will rust” (Harlap, 2024).

Ben-Gurion’s warnings after Israel’s War of Independence, and throughout his years in office, regarding the danger of an Ataturk-like leader rising to power in an Arab country and unifying them in a military action against Israel, is one example of the great caution that was typical of his leadership. It is what led Israel’s security system to prepare effectively for a clash with the Arab enemy and under no circumstances to belittle its capability. This worldview is what granted Israel victories on the battlefield, strategic successes, and relatively long periods of calm, enabling the state to develop its economy and to implement strategic warning systems that strengthen its security even now. Unfortunately, some of the Israeli leaders who followed Ben-Gurion did not adopt these aspects of his leadership and methods.

* The author would like to express his sincere thanks to the following people who contributed to the research and writing of this article: INSS interns: Ruth Poplavsky, Ido Karp, Omer Alalouf. Israel State Archives employees: Ayala Nahum, Yaniv Varulkar. The Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism employees: Mrs. Michal Laniado and Yefim Maghrill.

Bibliography

Ben-Gurion, D. (November 27, 1948). Diary of David Ben-Gurion. Ben-Gurion Archive [in Hebrew].

Ben-Gurion, D. (April 5, 1949a). Speech. Speeches File, Ben-Gurion Archive [Hebrew].

Ben-Gurion, D. (April 26, 1949b). Diary of David Ben-Gurion. Ben-Gurion Archive [Hebrew].

Ben-Gurion, D. (October 27, 1949c). Letter from Ben-Gurion to Chief of Staff Yadin. IDF Archive 1340/93/13 [Hebrew].

Ben-Gurion, D. (October 18, 1951). Speech. Speeches File, Ben-Gurion Archive [Hebrew].

Ben-Gurion, D. (September 11, 1958). Speech. Mapai Central Committee [Hebrew].

Ben-Gurion, D. (November 10, 1963). Article in Turkish newspaper. Item No. 8236, Ben-Gurion Archive [Hebrew].

Harlap, S. (June 17, 2024). The Rockets Didn’t Rust—They Even Got More Advanced. Ynet [Hebrew]. https://tinyurl.com/57y4763v

Hiram, E. (December 26, 1952). Ataturk: A Model to Emulate for Arab Leaders. Haaretz, p. 2 [Hebrew]. https://tinyurl.com/4bbwetza

Knesset Records (April 4, 1949). Twentieth session of the First Knesset, p. 305 [Hebrew]. https://tinyurl.com/4tj3xbhw

Knesset Records (February 22, 1960). Fifty-fifth session of the Fourth Knesset, p. 667 [Hebrew]. https://tinyurl.com/bdn9nssr

Lerman, H. (April 28, 1950). Turkey and Israel. Hed Hamizrach, p. 5 (from a website of historical Jewish journalism). https://tinyurl.com/5n7f5ten

Moshe Sharett & His Legacy (undated). Appendix Bekhiya L'Dorot, 1948-2013. Website of the Moshe Sharett Heritage Society [in Hebrew]. https://tinyurl.com/39r8dnts

Podeh, E. (2022). From Mistress to Publicly Recognized Partner: Israel’s Secret Relations with States and Minorities in the Middle East, 1948-2020. Am Oved [Hebrew].

Shalom, Z. (1995). David Ben-Gurion, the State of Israel, and the Arab World. Ben-Gurion Heritage Center [Hebrew].

Shalom, Z. (2023). The Roots of the “Concept” before the Yom Kippur War: Speech by Defense Minister Dayan to Senior Members of the Security Establishment, July 17, 1973. Strategic Assessment, 26(3), pp. 89-102 [Hebrew]. https://tinyurl.com/mpb87j2w

Siton, D. (May 26, 1950). Turkey is on a Democratic Track. Haboker [Hebrew]. https://tinyurl.com/vewt3fwh

Ya’alon, M. (2017). The Six-Day War: The Victory That Spurred a Fixed Mindset. In K. Michael, G. Siboni, and A. Kurtz (Eds.), Six Days and Fifty Years (p. 97-104). Institute for National Security Studies [Hebrew].

Zitun, Y., and Halabi, E. (October 7, 2023). In the Days before the Suprise Attack: Senior IDF Officials Told the Political Leadership that Hamas Was Deterred. Ynet [Hebrew]. https://tinyurl.com/3e53e598