Strategic Assessment

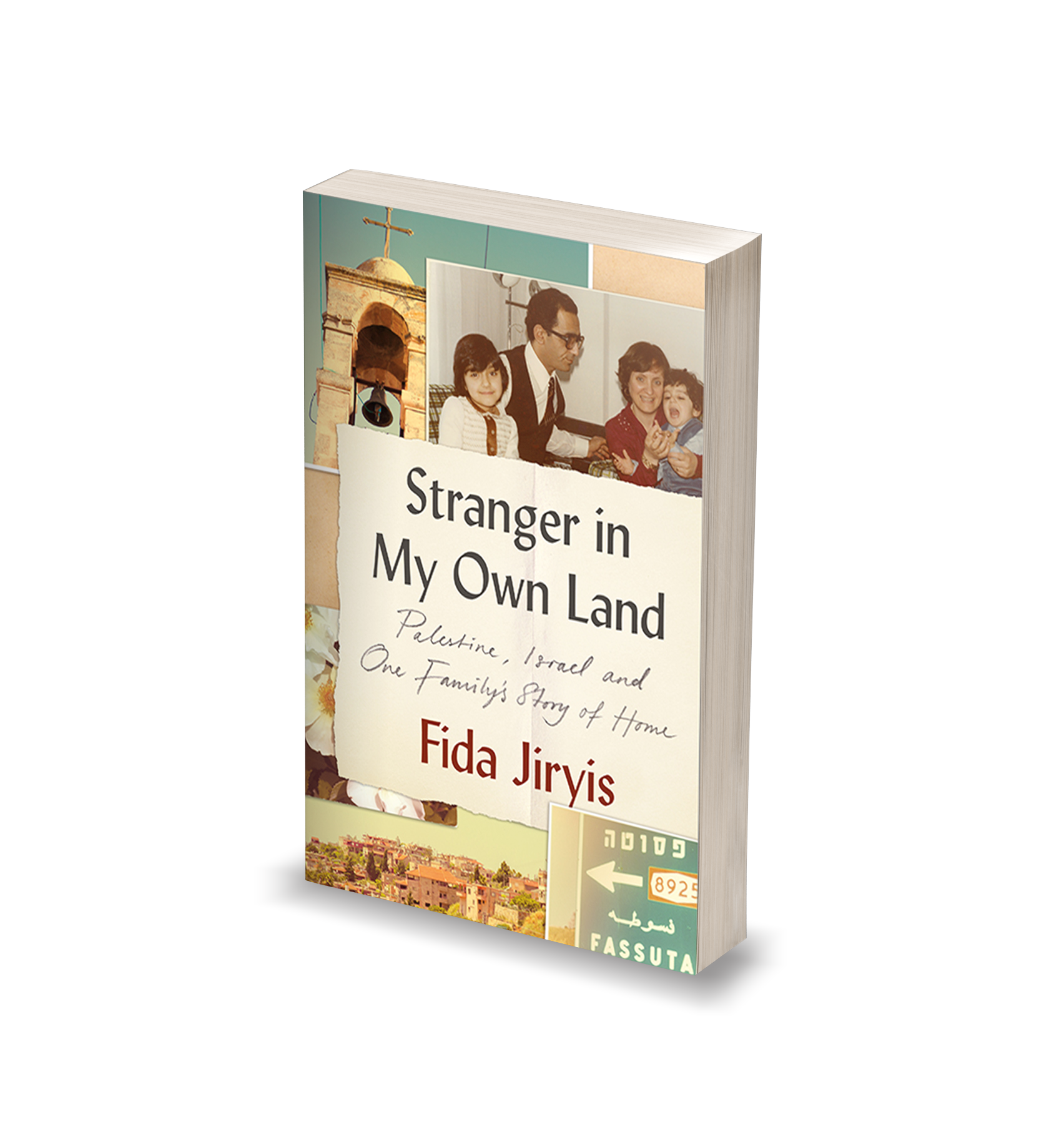

- Book: Stranger in My Own Land: Palestine, Israel and One Family’s Story of Home

- By: Fida Jiryis

- Publisher: Hurst

- Year: 2022

- pp: 447 pages

Seventy-five years after the establishment of the State of Israel and the creation of the refugee problem, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict continues, with no end in sight. The choices of the Palestinian national leadership in their attempts to lead their nation—initially the liberation of “Palestine” through armed struggle, and then a political, two-state solution—failed. That the PLO ignored the issue of Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel during the Oslo process made it clear that they themselves must face their fate and struggle for their status and their future in the state, and in practice strengthened the trend of their integration in Israel’s society and economy. At the same time, some members of the second generation of the “Nakba,” including Israeli citizen Fida Jiryis, are unwilling to accept the results of the Nakba and seek to turn the clock back to 1948.

Family Nakba Stories of the Second Generation

Although Fida Jiryis does not come from a refugee family, her autobiographical work can be categorized as part of a wave of literary creations by Palestinian women authors and poets, most of whom are the daughters of refugee families and live in the diaspora. They write in various styles about the events of the 1948 Nakba as their families and members of their people experienced it.[1] This literary phenomenon, which began some two decades after the Oslo process was revealed to be a failure—leaving the Israeli occupation intact while undermining the PLO’s role as representative of the Palestinian people—has generated interest among various researchers, particularly in light of the 75th anniversary of the Nakba and the establishment of the State of Israel.

This literature diverges from the establishment ideological literature of the Palestinian national movement that the PLO itself shaped, which served as a means of recruitment for the national struggle and a means to encourage armed struggle (Kanafani, 1966). The personal and familial stories of the Nakba, with the psychological trauma they entailed, were almost never told.[2] The new literature, written by members of the second generation, expresses an increasing need by Palestinian individuals to make their voices heard and to author their own personal narratives and the narratives of their families and their people. In this manner they seek to prove to themselves and to the world that they are surviving, continuing their lives, and maintaining their collective identity, in spite of becoming refugees in 1948 and in spite of the uprooting of 1967, as well as the decades of life under military occupation in conditions of ongoing national struggle. They thus prove the strength of Palestinian national identity and culture, which were maintained in the transition from one generation to the next.

The conclusion Jiryis reaches in her book is that the problem of the Palestinian people is with the 1948 Nakba and the establishment of Israel, and not with the 1967 occupation. This clearly places her in the company of writers such as Elias Khoury, who believe the “ongoing Nakba” is still underway, and that one must not reconcile with its consequences (Khoury, 2002).[3] This is in contrast to other writers, such as Emile Habibi (1988) and Mahmoud Darwish (2012), who took the approach that the Nakba was an event in the past and an established fact, and therefore the Palestinians must look ahead and build their future while finding a solution to the consequences of the 1967 war. The latter saw the center of gravity of the conflict with Israel as territorial, and therefore supported partition into two states, so that the return of refugees would be to the borders of the Palestinian state rather than to their homes from 1948.

Professor Said Zidani, an Arab Israeli living in Ramallah, has taken a public stand against the expression “the ongoing Nakba” and claims that it harms the Palestinian cause conceptually, politically, and educationally. He contends that the events of the Nakba took place between the UN decision on partition on November 29, 1947 and the ceasefire agreements between Israel and the Arab states that were concluded on July 20, 1949; during this time the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination on its land was denied, and two-thirds of Palestinians were uprooted beyond the borders of Palestine. In his eyes, any attempt to present crimes that took place against the Palestinian people afterwards as an ongoing Nakba originate in irresponsible conceptual confusion (Zidani, 2023).

The Autobiography of Fida Jiryis

The title of Jiryis’ autobiographical work represents its central, complex, and pretentious idea: to tell her personal story as a stranger, in exile while in her homeland, thus interweaving the story of the Palestinian people with the story of her family, from the onset of the conflict with Israel until the present day. The book opens with an introductory chapter overviewing the period from 1897-1948, starting with the first Zionist Congress and concluding with the establishment of the State of Israel and the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem. The author presents the Jews as a "religious community" and denies that Israel, which was established “on the historic land of Palestine,” is the nation-state of the Jewish people (p. 1). The following sixteen chapters describe events in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in chronological order, including the stages of armed struggle, popular uprisings, and the failed political process between Israel and the PLO. The author incorporates within this chronological framework her own personal story and the story of her family and her people, and presents them as victims of the 1948 Nakba, whose consequences are still felt today.

The book reflects the author’s despair at her gloomy personal situation as a member of the Nakba’s second generation, who in the fifth decade of her life feels lonely, is in the midst of a severe identity crisis, and has not found her place in her homeland. At the same time the book presents a dark picture of members of her people living in Israel, which she defines as an apartheid state, as well as those living in territories of the Palestinian Authority under Israeli military rule, which is described as tyrannical and oppressive.

Jiryis was born in 1973 in Beirut to a family that voluntarily left Israel in 1970 and returned in the wake of the Oslo process in 1995. The first decade of her life was spent in the shadow of the prolonged civil war in Lebanon and the Israeli invasion in 1982. In a chilling chapter of the book, “The Dark Hour,” she describes witnessing bombing from air, sea, and land during the siege of West Beirut, the limited supply of food, water, and electricity, and the urgent attempts to escape to hiding places during bombings, given the lack of shelters. “It was completely incomprehensible to us children; we saw the panic-stricken faces of the adults and watched normality evaporate,” she writes (p. 208).

Jiryis’ autobiography—the story of someone born and raised in exile who only set foot on her homeland for the first time at the age of 22, is suffused with disappointment at the reality of life there, and with desperate searching for home, identity, and belonging. When she comes to Israel she discovers that the “homeland was lost,” and her pessimistic writing expresses a deep, unforgiving anger at the State of Israel, for its policy toward its Palestinian citizens and the Palestinians living in PA territories, and for its opposition to the return of refugees to their homes. The content of her book reflects disappointment from her personal situation due to the foreignness and alienation she feels in her homeland, and despair at the chance of an agreement that would secure national independence for her people.

Jiryis’s story, narrated in the first person, begins in the 1940s in the Christian village of Fassuta in the hills of the Western Galilee, where her parents were born. Her work of her father, Sabri Jiryis, a lawyer and political activist with a developed Arab nationalist outlook, led to repeated arrests and severe limitations on his freedom of movement and activity imposed by the Israeli military government. This reality led him to emigrate voluntarily to Lebanon in 1970. There he managed the Palestine Research Center and influenced the development of pragmatic thinking on statecraft in the PLO during the 1970s and 1980s. Sabri served as Arafat’s political advisor and held secret meetings on his behalf with Jewish and Israeli individuals, including Nahum Goldman. The author’s mother was killed in February 1983 in a car bombing at the entrance to the building where the Palestine Research Center operated, which was most likely carried out by a Lebanese Christian organization.

The book tells the story of seven and a half decades of blood-soaked conflict between two national movements struggling for the same piece of land, characterized by asymmetric power relations and dwindling chances of resolution. The author, who is not a historian, tells the story of the conflict from a vantage point that is both personal-familial and Palestinian nationalist. Her effort to relate the details of the historical developments of the conflict is admirable, but readers will notice historical inaccuracies, missing contexts, and imbalanced descriptions. For example, the principled and absolute rejection by the Palestinians and Arab states of the two-state partition plan (Resolution 181), which was approved by the United Nations General Assembly on November 29, 1947, is not mentioned as context or as a direct cause of the war that broke out in 1948 (Zureiq, 1948). Jordan’s administrative disengagement from the West Bank in the summer of 1988 in the context of the first intifada, which constitutes a central historic event in the story of the Palestinian people, finds no mention in the book.

Encountering the Homeland, the Village, and the Family

The author’s encounter with the reality of life in the shadow of the national conflict between the State of Israel, of which she is a citizen, and the Palestinian people, to which she belongs, shook her world and offered her soul no respite. Her encounter with her homeland and her extended family raised questions about personal, social, existential, ethical, national, political, and religious identity—both in relation to Israeli Jewish society and in relation to Arab Palestinian society. Her encounter with the villagers of Fassuta was a clash of cultures. She quickly became aware of the deep cultural and social gaps between herself and them; they were members of a collective, patriarchal, conservative society, while she was a young individualist educated in the West.

Her accumulated experiences encountering her homeland and her exposure to the reality of life of her compatriots in Israel and the PA territories led the author to the conclusion that there is no difference between the Nakba and the occupation of 1947, on the one hand, and the Naksa and the 1967 occupation on the other hand. In her view, Israel is working to maintain its ethnic Jewish purity (p. 407), and its apartheid policy is directed at dispossessing Palestinians from their homes and their lands; Israel is systematically taking over their territories; and harsh violence is used against them on a daily basis (p. 429). In her view, Israel’s “conflict management” policy aims solely to perpetuate the occupation. She therefore criticizes the Palestinian leadership for continuing to believe in the Oslo Accords and the partition of the land between the two peoples.

The intergenerational comparison between the father, lawyer Sabri Jiryis, and his daughter, is unavoidable and fascinating. The father adopted the pragmatic political approach as early as the 1960s, within which he viewed the establishment of a Palestinian state on part of the homeland as a possible resolution; he influenced the outlook of the PLO leadership in this direction during the 1970s and 1980s. After the Oslo Accords he concluded that Israel was not interested in a political resolution that would lead to the partition of the land. His daughter, who with her arrival in her homeland experienced life both in Israel and in the PA territories, reached two main conclusions. First, the central problem of the conflict is not the 1967 borders, but rather the very existence of Israel as a state born out of ethnic cleansing in 1948, on lands stolen from the country’s native inhabitants. Second, the suffering, trials, and travails that the Palestinian people faced as a result of the establishment of Israel and the Nakba in 1948 continue today. She believes that if not for these events, her fate as the daughter of a family from an Arab village in the Galilee, like the fate of the Palestinians as a people, would necessarily be different, and better.

Consequently, the father, as a member of the generation that experienced the Nakba, and his daughter, as a member of the second generation, have an almost shared, despairing outlook, whereby there is no point in pursuing a pragmatic approach to the conflict with Israel or in endorsing a fruitless solution of partitioning the land into two states. Both also admit today that they feel like strangers in their homeland.[4]

The author’s outlook on the conflict is thus fundamentally pessimistic. Her book conveys the message there is no chance and there has never been a chance to achieve peace with the State of Israel. The element of her worldview that is nonetheless optimistic relates to the resilience of the Palestinian people. She boasts proudly of the fact the Palestinians within and outside their homeland continue to exist as a collective and to maintain their national identity, despite the Nakba and despite all attempts to dispossess them of their land, break their spirit, and blur their identity. It is true that the PLO leadership failed when it gave into the temptation to recognize Israel during the Oslo process, but in her words, the fact remains that one generation passed on and another took the reins, and the current generation is carrying on the national identity and leading the resistance, aspiring to end the occupation and fulfill the refugees’ right of return.

The Nakba as a Defense Mechanism against Personal and National Self-Criticism

It seems that the author’s description of herself throughout the autobiography as a direct victim of the Nakba, like the way she describes the Palestinian people, is a kind of defense mechanism that allows her to blame an external entity, namely, Israel. This defense mechanism makes any personal or national soul-searching or self-criticism superfluous, and makes it difficult to draw conclusions or lessons in order to correct a course or plan the future by setting realistic and achievable targets and progressing toward their implementation.

On the personal level, self-criticism would have allowed the author to relate to the traumatic events she experienced during her childhood in exile, including the loss of her mother and life in the shadow of war in a foreign country, and to understand their weight and their role as elements that influenced her personality and her adult life. Consequently, the lack of self-criticism and the one-sided and imbalanced presentation of existing reality denied her the ability to cope with her past, to free herself from the sense of victimhood, and to find her place in society and in her land. In a confession from the epilogue, she admits that since the time she arrived in her homeland, she has been struggling to find her place: “Is it as a ‘citizen’ in a state that discriminates against me and labors to negate my existence; a member of the Palestinian community in Israel that suffers as inferior citizens; or a Palestinian among my brethren in the Palestinian territory, whose lives are a story of suffering each day?" (p. 427).

In the same fashion the book lacks a measure of national criticism, regarding the weight of responsibility of Palestinian national movement leaders for the type of strategic decisions they made while waging an armed struggle for the liberation of Palestine, and later in waging a political struggle for a resolution with Israel. Thus, for example, the conduct of PLO factions in Jordan in 1969-1971, which led to their expulsion to Lebanon; Yasir Arafat’s support for Saddam Hussein during the 1991 Gulf War, which caused significant economic and political damage to the PLO; the nature of PLO decisions during the Oslo process, which allowed Israel to continue building settlements, left the occupation in place, and worsened the situation of the Palestinian people; and generation of the deep rift in the Palestinian arena between a national authority supported by the West and moderate Arab states, and an Islamic authority supported by Iran (al-Taher, 2019; Khalidi, 2006).

The fact is that the Palestinian leadership failed in its attempt to lead its nation to fulfilment of its national desires. Blaming Israel alone and abstaining from self-criticism prevent the possibility of recognizing strategic mistakes that were made and suggesting practical steps toward change and repair. Without a deep examination and profound soul-searching for the reasons behind the gloomy state of the Palestinian people, the Palestinians and their leadership will find it difficult to chart a practical path toward fulfilling their right to self-determination.

Along with Palestinian authors from the 1960s and 1970s who refused to accept the defeat of 1948, such as Ghassan Kanafani (Kanafani, 1963, 1966), the author too refuses to accept the fact of the Nakba. She believes that Israel is responsible for the situation of the Palestinians, and that repairing the results of the Nakba will only be possible after the wheel of history is rolled back, and the right of return for refugees is implemented in practice (Falah Saab, 2023). At the same time, she does not offer a practical path for the young Palestinian generation. She concludes her epilogue with a rhetorical question: “Yet, how long can this last against the winds of freedom, justice, human rights, and equality?"(p. 429).

Arab Authors in Israel: “There is Life after the Nakba”

Jiryis describes the conditions of her life as an Israeli citizen from the Arab-Palestinian minority, and projects her experiences onto the entire community. She portrays a dismal and hopeless reality, in which Israel works incessantly to negate the existence of the Arab minority. In so doing, she ignores the far-reaching benefits that members of this minority have enjoyed in terms of their social, economic, and political status and their many accomplishments, notwithstanding the discriminatory policies they have suffered. They have come a long way in terms of social and cultural interaction with the Jewish society in which they reside, and the new middle class that has emerged within their ranks is struggling to achieve full rights as citizens and indigenous people. This trend was given added impetus by the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s decision to ignore their interests during the political talks with Israel, since Arab citizens of Israel learned that they would have to look out for their own status and future as a minority in Israel. They demand full partnership in the decision making process of Israel and recognition that they are an integral part of Israeli society.

In factual terms, Arab society in Israel is forming itself increasingly into a (civilian) community, separate from the other parts of the Palestinian people, and the vast majority of its members are not willing to renounce their Israeli citizenship for citizenship of any other entity. This is notwithstanding the fundamental national tension that exists and the sense of exclusion and alienation from the Jewish state, given laws like the nation-state law. They are increasingly integrated into the Israeli economy, society, culture, higher education, government, the healthcare system, and a wide range of other vocations; they contribute to the building of the country and they engage in broad reciprocal trade with the Jewish society in many areas.

Many members of Arab society in Israel today have a hybrid identity, Palestinian and Israeli, and unlike the author, they recognize Israel’s right to exist, even if they object to its self-definition as a Jewish state. This dual identity provides them with an opportunity to free themselves from the traditional frameworks that were forced upon their parents’ generation. Arab writers from the second generation after the Nakba, for example, who were raised on a culture that was committed to the national struggle and dedicated to memories of the lost homeland, understood that dealing exclusively with the conflict led to the atrophy of Palestinian creativity. These writers are now determined to turn over a new leaf and address “life itself” in their writing, since, as they see it, the Palestinian story is not just checkpoints and rocks. They seek to generate a significant change in the social and cultural structure and want to address painful issues in the patriarchal Arab society, such as the status of women and homophobia (Bsoul, 2017).

Even those who still address the national issue now offer a different perspective on the conflict. Take, for example, Prof. Nidaa Khoury, the poet and writer from Fassuta, who has been a standard bearer for the Palestinian national struggle for decades and is now calling for the Israeli and Palestinian sides to end their struggle for territory. She proposed a humanist and universalist approach that would be more suited to the new era of humankind, which exists in a virtual space where there are no borders. This kind of thinking, she explains, will allow nations to liberate themselves from the traumas of the past and from a place of victimhood, and to focus on freeing people and society from the chains of tradition and religion (Goldberg, 2009).[5]

In conclusion, writing an autobiography might have been therapeutic for Fida Jiryis and might have helped her overcome the scars she suffered in the past. Combining her personal story with the Nakba and the Palestinian tragedy allowed her to be part of the collective and to place the blame for her dire situation on an external element, i.e., Israel, but, at the same time, it prevented her from looking inward at herself, something that is essential in healing traumatic, unresolved experiences from the past.

It seems, therefore, that the Western audience that she was aiming for in her book, which was written in English, can get only a general idea about the conflict and identify with the sense of victimhood that accompanies her. Israeli readers, meanwhile, will no doubt find it hard to accept the content of the book, especially given its one-sidedness, its limited credibility, and its being an indictment against Israel as a purported apartheid state. Israelis will see it as a manifest for the Palestinian national narrative more than an autobiography in which one can identify with the protagonist.

References

Abulhawa, S. (2006). Mornings in Jenin. Bloomsbury.

Abulhawa, S. (2015). The blue between sky and water. Bloomsbury USA.

Al-Taher, M. (2019, September 27). Eight strategic mistakes of the Palestinian movement. al-Araby al-Jadeed. https://tinyurl.com/mrk5t8j2 [in Arabic].

Bsoul, J. (2017, June 1). Life after the Nakba: A new beginning for Palestinian literature. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/dtrtbu9x [in Hebrew].

Darwish, M. (2012). What to do after Shakespeare? On Palestine, poetry, love, and life. al-Carmel al-Jadid 3-4, 43-44 [in Arabic].

Falah Saab, S. (2023, January 5). Fida Jiryis: I will never agree to be treated like a second-class citizen. Who do you think you are? Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/ynzdsejm [in Hebrew].

Goldberg, A. (2009, April 28). Land is no longer a prerequisite for a nation to exist. Interview with poet and author Prof. Nidaa Khoury. Beit Avi Chai. https://tinyurl.com/dnfe6763 [in Hebrew].

Habibi, E. (1988). Akhtia. (trans. From Arabic: A. Shams). Am Oved, Proza Aheret [in Hebrew].

Jiryis, S. (1966). The Arabs in Israel. Al-Ittihad.

Kanafani, G. (1963). The land of sad oranges. al-Ittihad al-Ahm [in Arabic].

Kanafani, G. (1966). Resistance literature in occupied Palestinian, 1948-1966. Dar al-Adab [in Arabic].

Khalidi, R. (2006). The iron cage: The story of the Palestinian struggle for statehood. Beacon Press.

Khoury, E. (2002). The ongoing Nakba. Majallat al-Dirasat al-Filastiniyya, 89, 37-49 [in Arabic].

Khoury, E. (2013, July 22). The ongoing Nakba and the Prawer plan. al-Quds al-Araby [in Arabic].

Melamed, A. (2019, November 23). Fida Jiryis came back to her homeland, but still feels foreign.” Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/ycxnm4ja [in Hebrew].

Sayigh, R. (2013). On the exclusion of the Palestinian Nakba from the “trauma genre.” Journal of Palestine Studies, 43(1), 51-60. https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2013.43.1.51

Steinberg, M. (2015). The Nakba as trauma: Two Palestinian approaches and their political repercussions. In A. Jamal and E. Lavie (Eds.), The Nakba in the Israeli national memory (pp. 98-112). Tel Aviv University: Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research and the Walter-Lebach Institute for Jewish-Arab Coexistence [in Hebrew].

Zidani, S. (2023, April 13). Two concepts of the Palestinian Nakba since ‘48. al-Quds [in Arabic].

Zureiq, C. (1948). The meaning of the Nakba. Dar al-Ilm lil-Malayeen [in Arabic].

_________________

[1] One of the best-known is Susan Abulhawa, daughter of parents from East Jerusalem who now live in the United States. Her debut work, Mornings in Jenin (2006), describes the travails and tragedies of a Palestinian family expelled in 1948 from the village of Ein Hod who ended up in the Jenin refugee camp. Her second book, The Blue Between Sky and Water (2015), also relates the history of a family expelled in 1948 from the village of Beit Daras, which was destroyed and burned down, and the long and difficult journey to a refugee camp in Gaza. The two books were translated into 20 languages and became global bestsellers.

[2] See in this context the article by Rosemary Sayigh (2013) discussing that almost no literature describing “trauma from the past” was written about the 1948 Nakba. The exception is Ghassan Kanafani’s 1963 autobiographical novel.

[3] This motif repeats itself in Khoury’s weekly column in al-Quds al-Araby. See for example his commentary on the Israeli plan to regulate the Bedouin issue in the Negev (the “Prawer plan”) (Khoury, 2013).

[4] The title of the author’s book, Stranger in My Own Land, is very similar to the title of one of the chapters of the important 1966 book by her father, Sabri Jiryis, The Arabs in Israel, “Strangers in Their Own Land.” This was the first book written in Hebrew on the Palestinian minority in Israel. The book was translated into Arabic and other languages. See also Melamed, 2019.

[5] From an interview conducted by Amit Goldberg with poet and writer Prof. Nidaa Khoury.