Publications

INSS Insight No. 1626, August 9, 2022

The resumed employment of workers from the Gaza Strip in Israel over the last few years – after the suspension following the disengagement in 2005 – was intended to further the relative security calm and restrain Hamas from escalation. After the COVID-19 pandemic ebbed in October 2021, the income of Gazans entering Israel for work grew by more than six-fold, yet approximately one third of these workers paid for entry permits to Israel. Regulation of employment in Israel beginning in August 2022 may harm those employed in the manufacturing and service industries, which were not allocated permits to employ Gazans; may reduce net wages due to mandatory social deductions; and will likely strengthen employers’ control of permits. On the other hand, regulation enables employment opportunities in additional companies and may provide welfare benefits, such as pensions and health insurance. Gazan workers in Israel typically do not have higher education, in accordance with the criteria set by Hamas and the nature of employment in Israel, and this erodes the status of Gazans with higher education.

On August 1, 2022, regulation of the employment in Israel of Gaza residents commenced with a system of work permits and formal employers in the construction and agriculture sectors. This article presents the findings of a study that examines Gazans’ employment in Israel prior to this regulation, in which Gazan workers entered Israel via “economic need permits.” The findings presented are thus for unregulated activity; future studies will examine the effects of employment regulation on employment and employee wages and welfare benefits.

What follows is the first statistical analysis of Gazan employment in Israel after its unofficial renewal over the last few years. Before the second intifada, employment in Israel constituted an important source of income for Gaza residents, and at its peak in 1986, 46 percent of the Gazan workforce was employed in Israel. Official employment in Israel ended after the 2005 disengagement as part of a plan to create a political separation between Israel and the Gaza Strip. Unofficial employment of “Gazan merchants” was tolerated since 2014, ceased temporarily with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020), and was renewed in October 2021 as the pandemic ebbed.

The primary database for this study is a phone survey of 1,000 Palestinian workers, which was conducted by the Palestinian Center for Public Opinion (managed by Dr. Nabil Kukali). The survey was conducted in May-June 2022 and gathered data on employment in Gaza in September 2021, prior to the renewal of Gazan employment in Israel, and on employment in Israel from October 2021 to April 2022. The distribution of interviewees by age and residential area was determined based on the distribution among holders of economic need work permits. Some of these analyses also made use of microdata data from the Palestinian Labor Force survey, in order to allow comparison with data on Gazan workers in Israel.

Renewal of Gazan Employment in Israel

In October 2021, as the COVID-19 pandemic ebbed, the Israeli government decided to resume Gazan employment in Israel. Currently, about 11,000 Gazan workers have entry permits and are employed informally. In March 2022 the government decided to regulate Gazan employment in Israel and allocate 20,000 work permits to Gazans, 12,000 for the construction industry and 8,000 for agriculture. The permits are given to married Gazans aged 25 and up who have passed a security check. The policy of the Hamas Ministry of Labor is to allow employment in Israel of married Gazans aged 27-60, who are not employed in the public sector and do not have an academic degree, and are not entitled to public stipends. Likewise, Hamas prefers to allocate work permits in Israel to unemployed Gazan men with large families whose wives do not work.

The comparison between Gazans working in Israel and those working within Gaza reflects the respective Israeli and Hamas policies. The average age of Gazans employed in Israel is 44, and the average age of workers within Gaza during their primary working years (25-64) is 39. While some 40 percent of men aged 25-64 in Gaza have some post-secondary education, only 17 percent of Gazan workers in Israel have post-secondary education. In addition, some 83 percent of Gazans employed in Israel report that they were not working in September 2021, before the resumption of employment in Israel.

From Lower Middle Class to the Highest Decile

Gazan workers experienced a sharp increase in income in the wake of the transition to employment in Israel. Only 17 percent of the Gazans who work in Israel reported that they worked in Gaza in September 2021, and their monthly wage was NIS 1,040, well below the average wage of NIS 1,600 in Gaza in the third quarter of 2021. The average wage of all Gazans who began working in Israel rose more than six-fold, to some NIS 6,350 per month (Figure 1). The wage differential between Gaza and Israel allows various elements to charge payments for the permit: around one third of the workers paid an average sum of NIS 2,830, and a small minority of these workers paid in subsequent months as well. Nevertheless, increased wages are also reflected in these workers reporting an average level of 6.8 in “happiness” which is higher than self-reported “happiness” in the West Bank and Gaza (4.5) and in Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (6.6). Most Gazan workers indicated that their Israeli employers treat them “very well” (49 percent) or “well” (11 percent), and only one-third of the workers say that their employers treat them badly or very badly.

Figure 1: Wages of Gazan workers in Gaza and in Israel, NIS per month

Sources: Gazan workers in Israel survey and Palestinian workforce survey

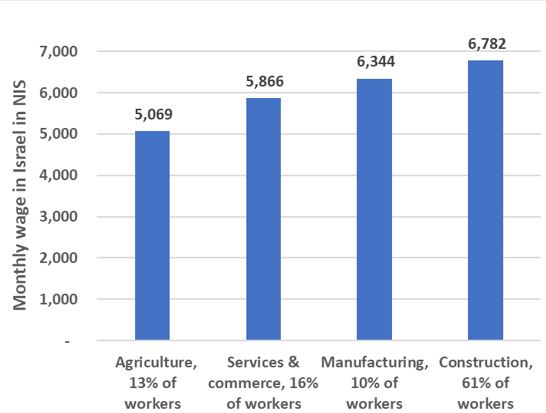

The survey found that 61 percent of Gazan workers in Israel are employed in construction, and that the average wage in this sector (NIS 6,780 per month) is high compared to other sectors. The average wage in agriculture, which employs one-eighth of these workers, is the lowest (NIS 5,070). One-quarter of the workers are employed in industry, services, and commerce, with an average wage of NIS 5,850-6,300 (Figure 2). The proportion of workers employed in the construction sector is commensurate with the government permit allocation of 60 percent, but the proportion of workers employed in agriculture is lower than the 40 percent allocation, and the manufacturing, services, and commerce industries were not allocated work permits for Gazans. Compelling workers in these sectors to move into agriculture is likely to generate difficulties, including wage reductions.

Figure 2: Average Monthly Wage and Rate of Workers by Employment Sector in Israel, in NIS and percent

Source: Gazan workers in Israel survey

Geographically, around half of the workers are employed at a higher wage in the Tel Aviv region (NIS 6,850) or north of Tel Aviv (NIS 6,550); one half is employed in the south at a lower wage (NIS 5,900 per month). The higher wages in the Tel Aviv region and the north will likely draw more Gazan workers as they become familiar with the Israeli labor market. Ay any rate, it should be considered whether and how workers can be brought back to Gaza from different regions of Israel in the event of a military confrontation.

Implications for Policy Regulating Gazan Employment in Israel

The resumption of Gazan employment in Israel at its current scale, with some 11,000 permits, and its expansion to 20,000 permits in accordance with government decision #1328 (March 27, 2022) benefit those working in Israel and their families. According to the survey, workers in Israel reported that their wages are very high by Gazan standards, they are treated well by their Israeli employers, and their personal welfare levels are very high. These workers, prior to their employment in Israel, came from the lower middle class. In accordance with the criteria set by Hamas they do not have academic education and the vast majority were not working in September 2021, immediately prior to the renewal of employment in Israel. Employment in Israel thus improved the situation of Gazans with lower levels of education, and in a relative manner thus weakened the status of those with higher levels of education. The latter may protest the Hamas decision to prevent them from working in Israel, particularly as Hamas has paid only a portion of the salaries owed to its workers in recent months due to a budgetary crisis.

It is doubtful whether Gazan employment in Israel at this scale will lead to significant economic growth in the Gaza Strip, given that local manufacturing capacity has declined dramatically since Hamas rose to power. Likewise, it is doubtful whether employment in Israel will increase the Gazan employment rate, beyond the number of Gazans employed in Israel.

Regulating Gazan employment in Israel brings workers from an unregulated market into a regulated market, in which employers are obligated to report working days and hours and to withhold payments for taxes, National Insurance, and pensions. This regulation will allow workers additional employment opportunities with companies that only employ formal workers. However, the employers will be given control of the permits, which will reduce worker bargaining power vis-à-vis employers, particularly in agriculture where work permit quotas are under the full control of employers. Institutionalizing employer control of permits is likely to lead to problematic phenomena as in the West Bank, such as charging fees for permits. Payments for permits are likely to be especially high for workers leaving the impoverished Gaza Strip.

In addition, one quarter of these workers are currently employed in the manufacturing, commerce, and service industries that have not been allocated permit quotas. Moving these workers into agriculture, in which wages are relatively low, will harm many workers, and the quotas by economic sector ought to be reconsidered. Regulation might currently harm the workers’ net pay but will probably also open new avenues of employment and grant workers welfare benefits such as pensions and health insurance. Regulating Gazan worker employment with registered employers will probably also make it easier to take workers back to Gaza in the event of a military confrontation.

In the internal Palestinian arena, Hamas control of the distribution of permits to work in Israel, which contrasts with the lack of Palestinian Authority control, is another indicator of the sovereign power of Hamas in comparison with the weakness of the Palestinian Authority. Hamas likewise coordinates the allocations of Qatari aid funds to families that do not have a breadwinner working in Israel. This was probably not the intent of the policy.

Strategically, Israel stopped employing Gazans in Israel following the disengagement in order to create an economic and political separation between itself and the Gaza Strip. Over the last few years, employment of Gazans in Israel was resumed as a means to restrain Hamas and maintain security calm. It is worth examining how and whether enhancement of economic ties between Israel and the Strip, inter alia through the employment of Gazans in Israel and new formal regulations that govern such employment, strengthen perceptions of Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip as a single territory.