Publications

Special Publication, December 2, 2021

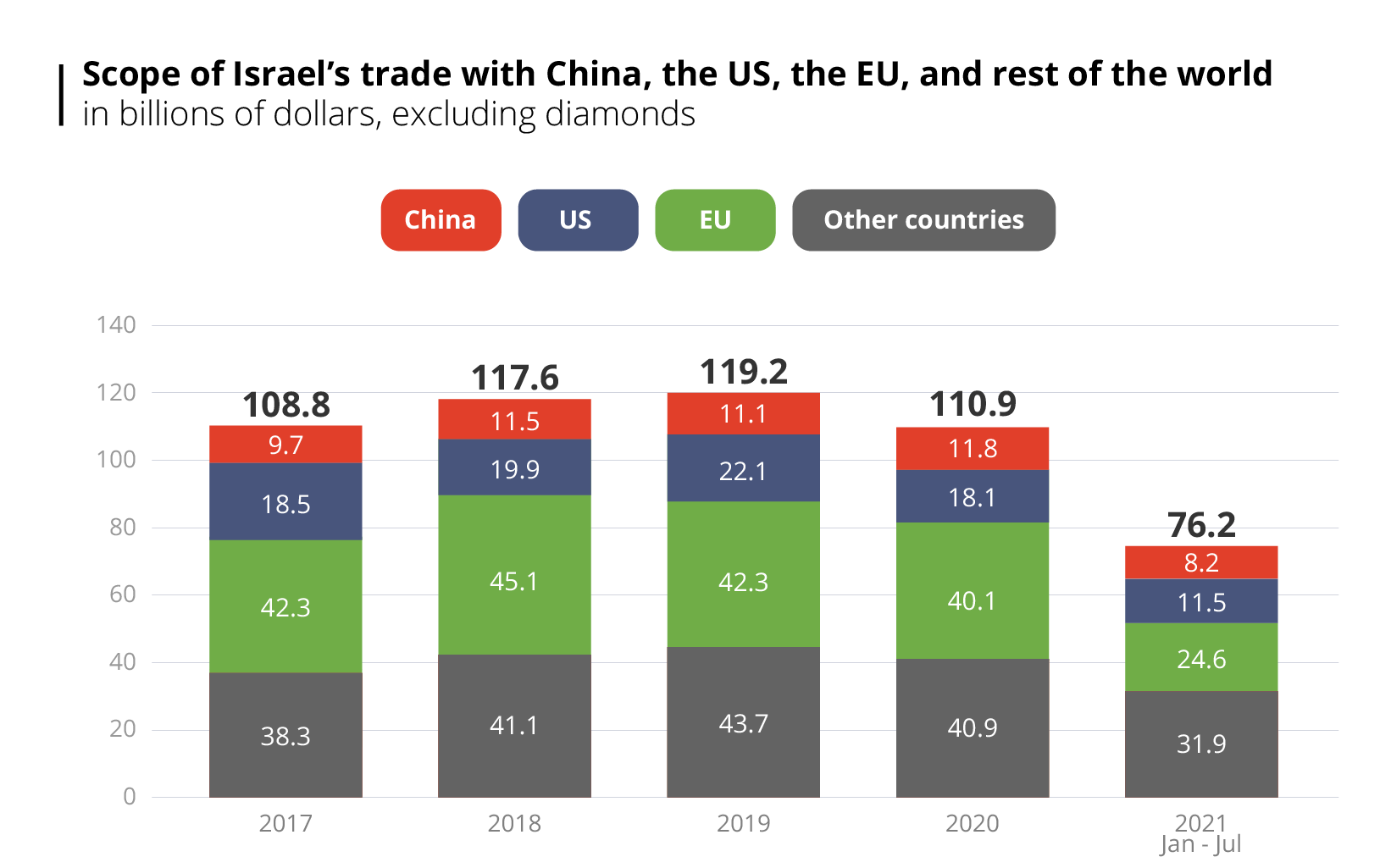

This article reviews trends in goods and services trade between Israel and China over the past decade, with an emphasis on 2020, when the world grappled with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods used by countries to handle recurring outbreaks of the disease included varying levels of lockdowns, which led to a reduction of economic activity, prompting economic and financial uncertainty and even significant crises in certain sectors. The economic crisis and uncertainty affected some trends in international trade: while Israel’s trade with some countries declined, in other cases it actually grew, changing according to the developing needs of countries in this period. Israel’s trade relations with China, in both goods and services, were not greatly affected by the crisis (apart from tourism, which was halted completely). However, the extent of trade in goods with China is still relatively low. In 2020 this market was worth $11.9 billion, lagging far behind trade with the United States ($18 billion) and the European Union ($40 billion). Trade with China accounts for almost 11 percent of Israel’s total trade in goods, and less than 2 percent of its trade in services.

Trade in Goods

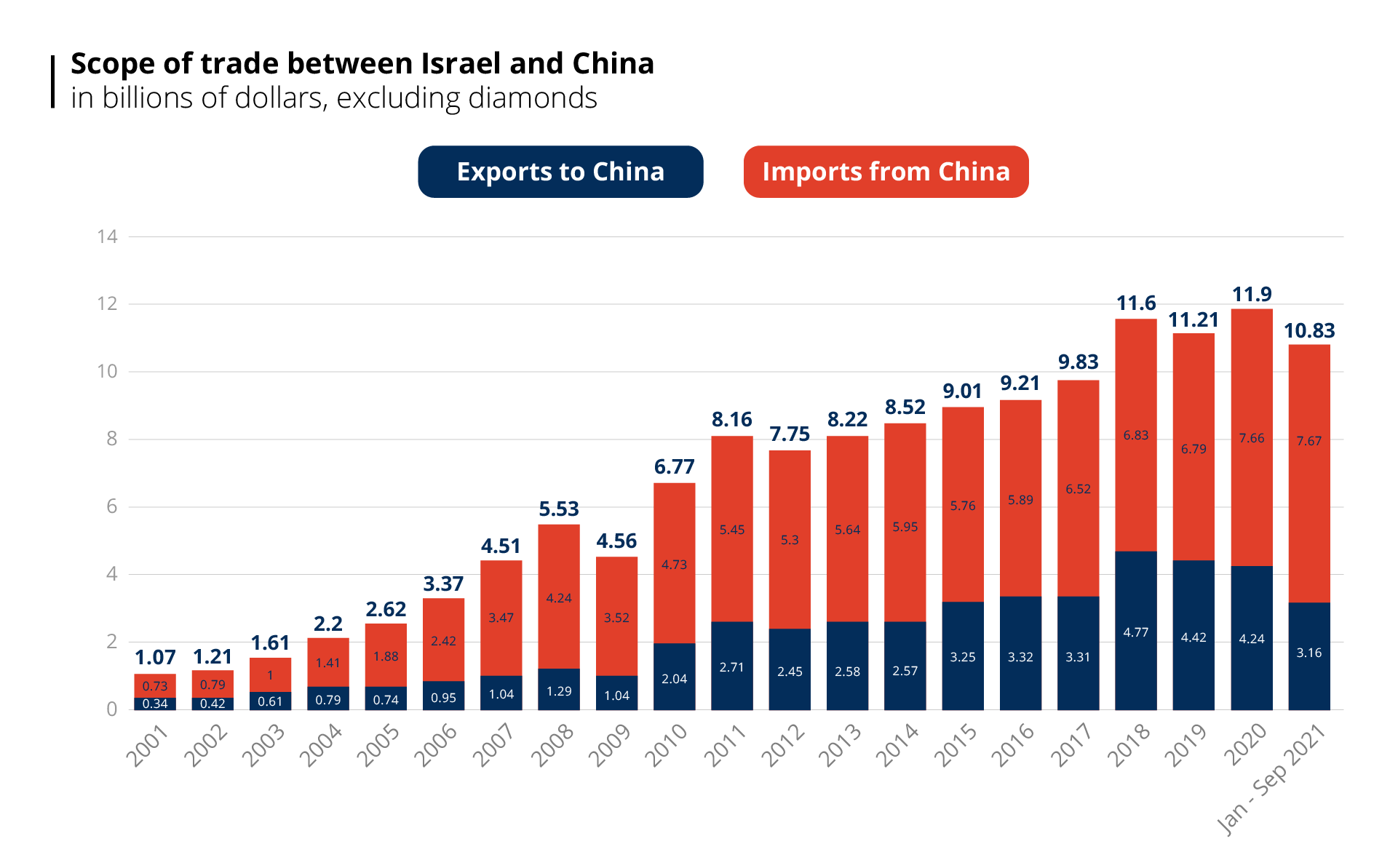

Trade in goods between China and Israel grew considerably over the past two decades. According to figures from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), in 2001 trade between Israel and China was worth $1.07 billion, and in 2020, it had reached $11.9 billion dollars (Figure 1). China (excluding Hong Kong) became Israel’s third largest trading partner, but remained significantly behind the United States ($18 billion in 2020) and the European Union ($40 billion in 2020) although Israel’s trade with China exceeds its trade with any single European partner (Figure 2).[1] The scope of trade with China, relative to all Israel’s international trade, is also increasing steadily: In 2017 trade with China accounted for 8.88 percent of all Israel’s foreign trade, and in 2020 reached 10.66 percent. However, throughout this period Israel suffered a trade deficit with China as imports from China had more than doubled Israeli exports to China. Israeli exports of goods to China reached a peak in 2018, when they were worth $4.77 billion, but since then they have declined, and in 2020 were worth only $4.22 billion dollars. At the same time, however, imports from China to Israel are steadily increasing, and in 2020 reached a record high of $7.66 billion.[2]

Figure 1: Trade between Israel and China in billions of dollars, excluding diamonds (2001-September 2021) | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

Figure 2: Israel’s trade with China, the US, the EU, and rest of the world in billions of dollars, excluding diamonds (2017-July 2021) | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

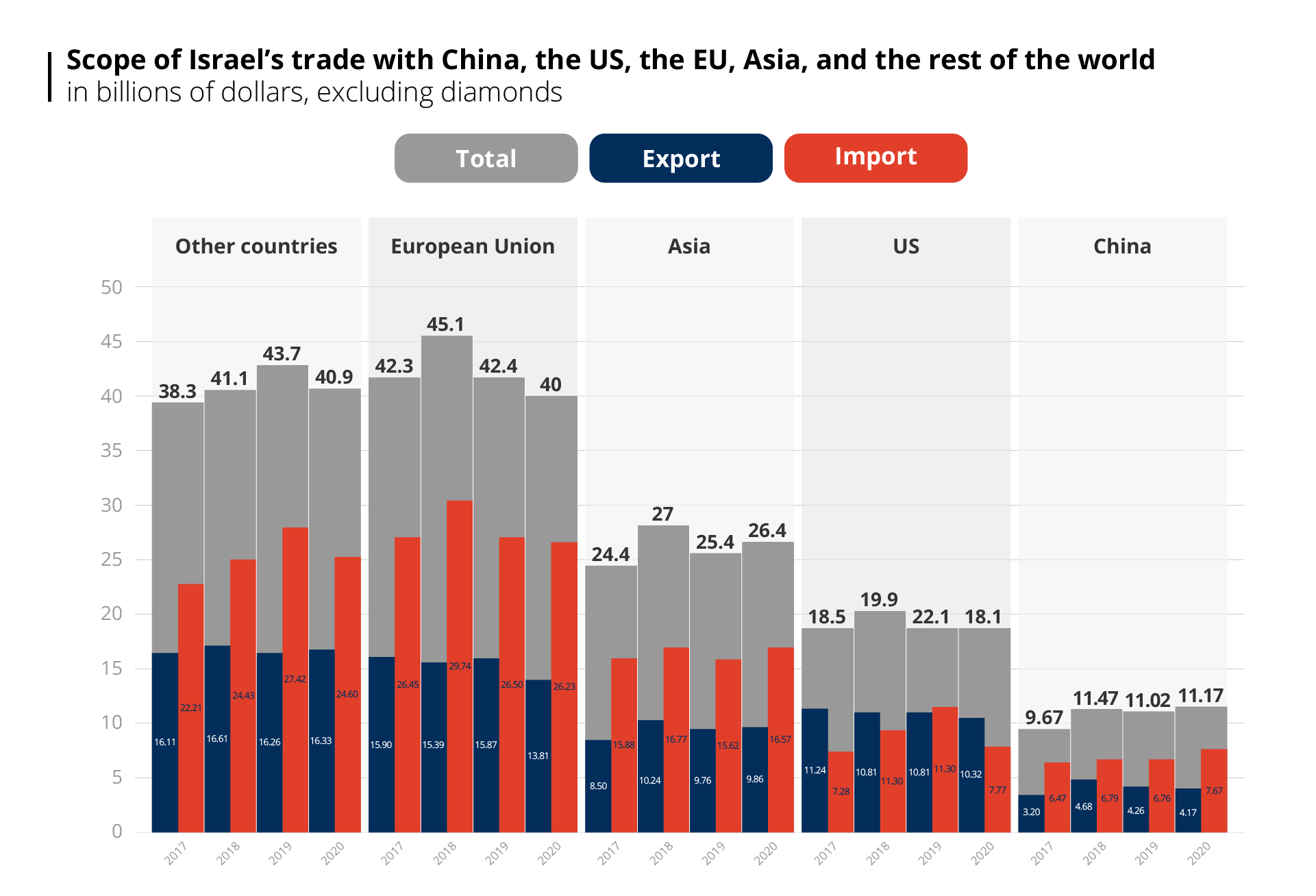

In comparative terms, in 2020 trade with China constituted 10.7 percent of Israel’s global trade, which amounted to $110.8 billion, and about 45 percent of Israel’s trade with Asia, which amounted to $26.4 billion. That year trade between Israel and the European Union fell to about $40 billion, representing 36 percent of its total foreign trade, after a record $45.1 billion in 2018. Similarly, Israel’s trade with the US also fell in 2020 to about $18 billion, 16.2 percent of its total foreign trade, compared to $22.1 billion in 2019 (Figure 3). In 2020, while Israel’s foreign trade in general, and with the US and the EU in particular, decreased, trade with China actually increased. In the first half of 2021, Israel’s trade with China still showed an upward trend, and from January to September was worth $10.83 billion, of which $3.16 billion were for exports to China and $7.67 billion dollars were for imports. If this trend continues, trade for the year should exceed the figures recorded for 2020. Therefore, the growth and composition of Israel’s economic relations with China should be examined carefully in order to find new opportunities and reduce potential risks.

Figure 3: Scope of Israel’s trade with China, the US, the EU, Asia, and the rest of the world, excluding diamonds, in billions of dollars (2017-2020) | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

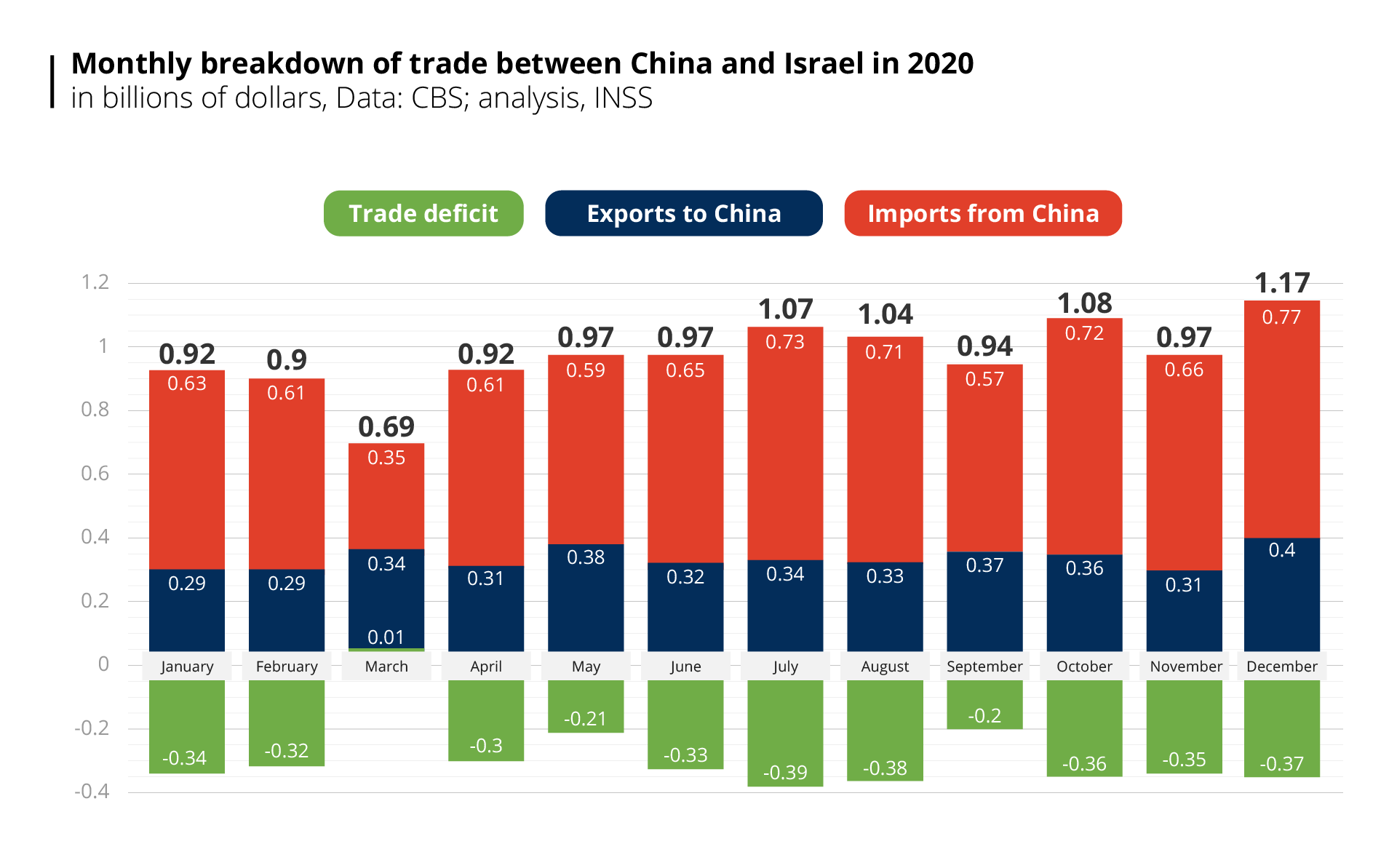

In 2020, monthly trade in goods between China and Israel averaged $970 million, of which monthly imports averaged $632.5 million. In March, when the outbreak of COVID-19 was first described as a global pandemic by the World Health Organization and promoted the first lockdown in Israel, trade fell to a low point of $690 million (Figure 4), and imports from China dropped significantly to about $338.1 million, compared to $408.7 million for imports from China in March 2019. However, the scope of trade in goods between Israel and China in 2020 was larger by $690 million than in 2019, due to an increase of $870 million in imports from China, together with a decrease of $180 million in Israeli exports. Similarly, in March 2020 trade with the European Union amounted to $3.2 billion ($2.3 billion of imports from the EU and $926 million of exports to the EU), a sharp fall from trade of $5.3 billion in 2019. Trade with the United States amounted to $1.5 billion in March 2020 ($640 million of imports and $932 million of exports), a slight drop from $1.7 billion in March 2019. On the other hand, in March 2021, Israel’s trade with China increased to $1.14 billion, of which $796 million were imports and $345 million were Israeli exports to China.[3]

Figure 4: Monthly breakdown of trade between China and Israel in 2020 | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

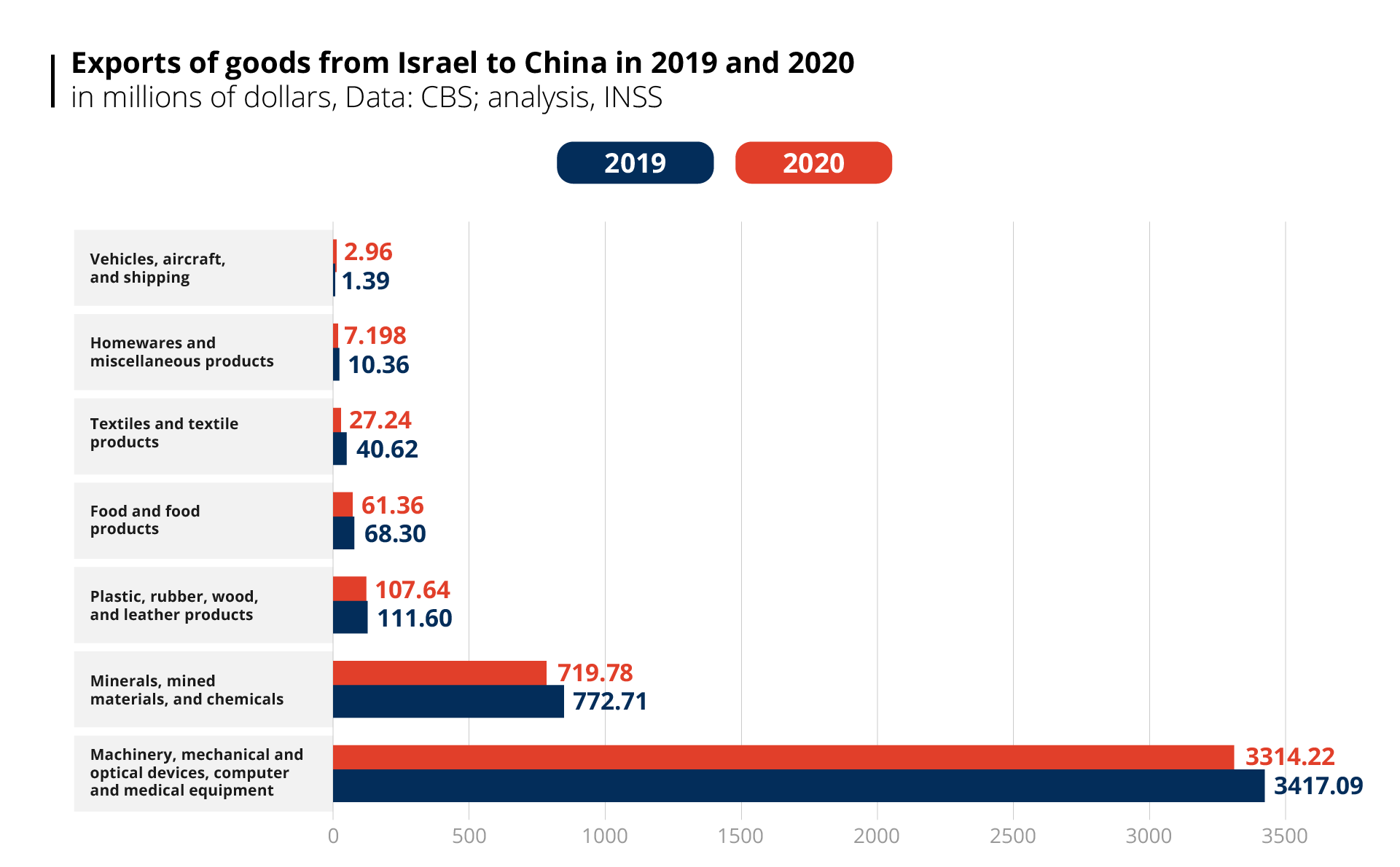

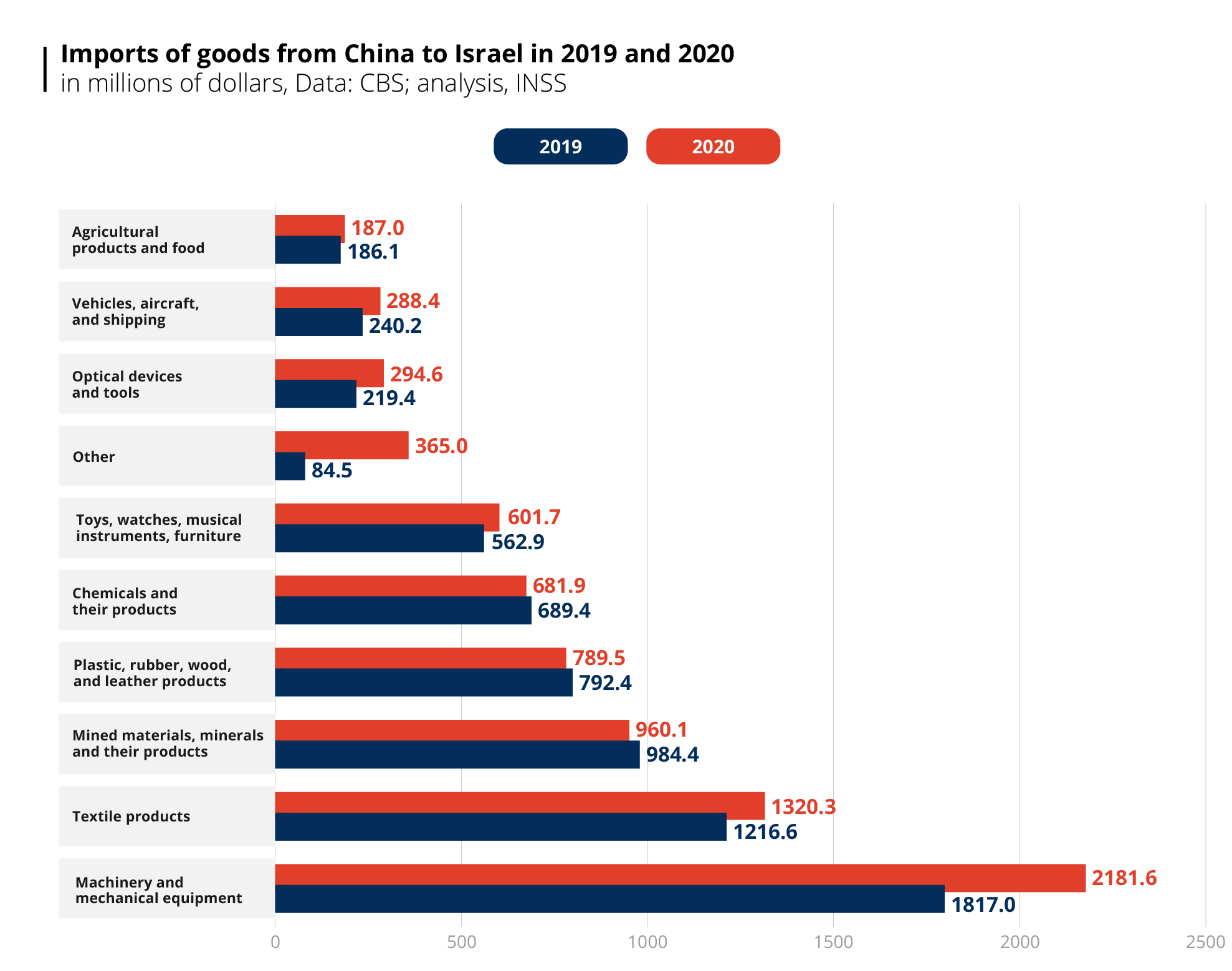

The decrease in Israeli exports to China in 2020 was mainly due to a drop of $102 million in exports of machinery, mechanical and optical devices, and computer and medical equipment, and a drop of $52 million in exports of minerals, mined materials, and chemicals (Figure 5). The rise in imports from China to Israel in 2020 was reflected in a number of sectors. First, a rise of $364 million was recorded in imports of machinery and mechanical equipment, which includes $198 million for the one-time purchase of cranes for construction of ports in Israel.[4] A rise of $200 million was also recorded in the import of goods, including personal packages with values up to $75 – apparently purchases by private individuals on Chinese shopping sites such as AliExpress, which also included face masks. In addition, there was a rise of $103 million in imports of textile products from China (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Exports of goods from Israel to China in 2019 and 2020 (in millions of dollars) | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

Figure 6: Imports of goods from China to Israel in 2019 and 2020 (in millions of dollars) | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

Trade in Services

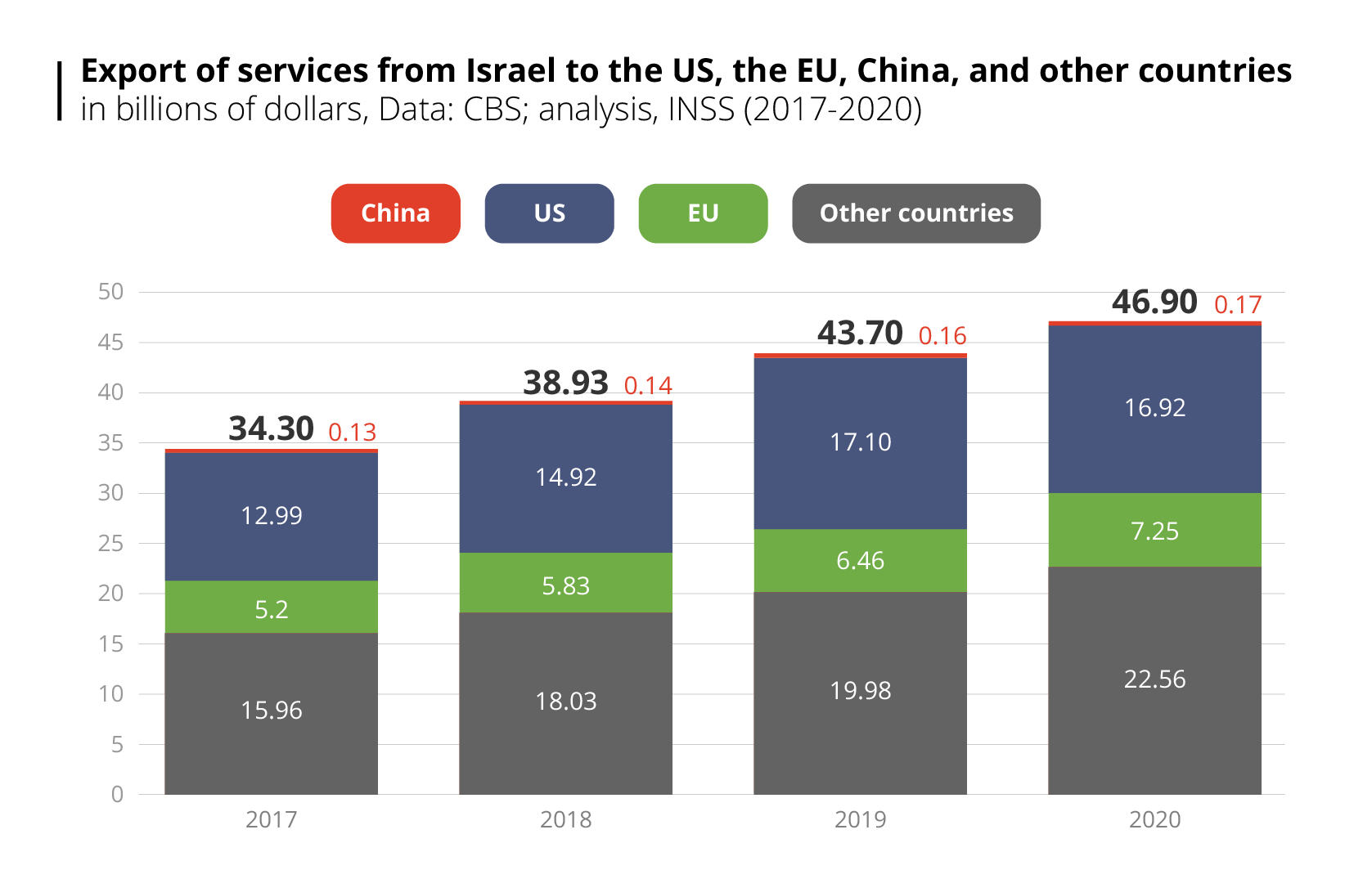

According to CBS data, trade in business services between Israel and China is very limited. Between 2017 and 2020, Israel exported services to China for $601 million, about 0.36 percent of Israel’s total service exports, which amounted to $163.8 billion in that period. Although there was a rising trend in Israel’s exports of services to China in those years, the tiny overall volume makes this sector almost irrelevant, particularly in comparison to the export of services to the United States, which amounted to $61.9 billion over the same period (about 37.7 percent of all service exports), or compared to trade in services with the European Union, which amounted to $24.7 billion (15 percent of all service exports; Figure 7).

Figure 7: Export of services from Israel to the US, the EU, China, and other countries, in billions of dollars (2017-2020) | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

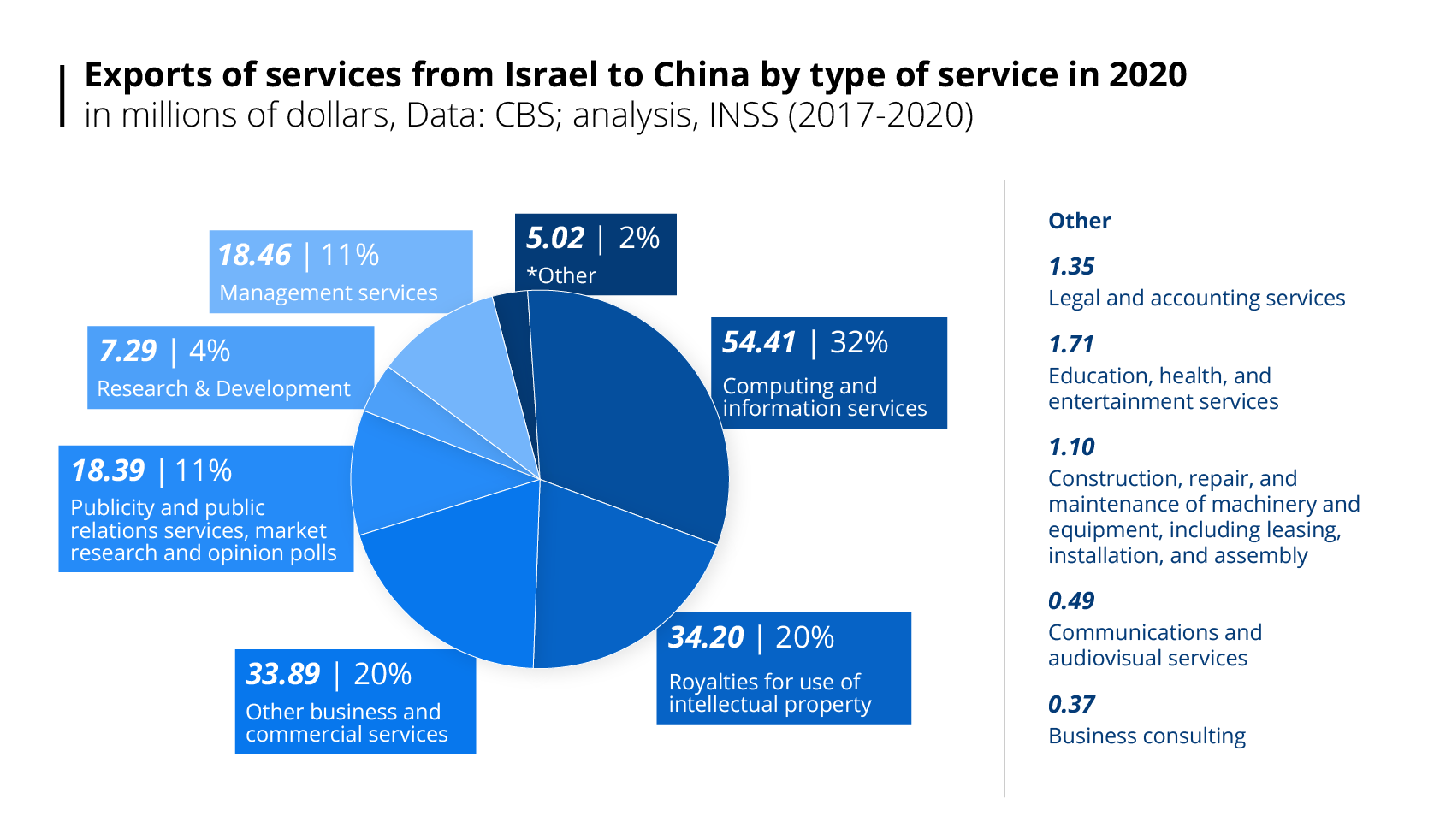

In 2020, exports of computing and information services (including research and development in software) amounted to about 32 percent of all service exports to China (some $54 million), and these have risen steadily over the past decade. Two other important branches of exports of Israeli services to China are royalties for the use of intellectual property (about 20 percent of service exports to China), and commercial and other business services, which together also account for 20 percent of service exports to China (Figure 8). In comparison, in 2020 export of computing services to the European Union amounted to $3.23 billion (about 44 percent of total service exports to the EU), while exports of these services to the United States amounted to $7.5 billion (also about 44 percent of total service exports to the US). It follows that the export of services to China is relatively varied (compared to the export of Israeli goods to that country), but the volume of exports is very small, particularly in view of the size of the Chinese market and its importance in the global economy.

Figure 8: Exports of services from Israel to China by type of service in 2020 (millions of dollars) | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

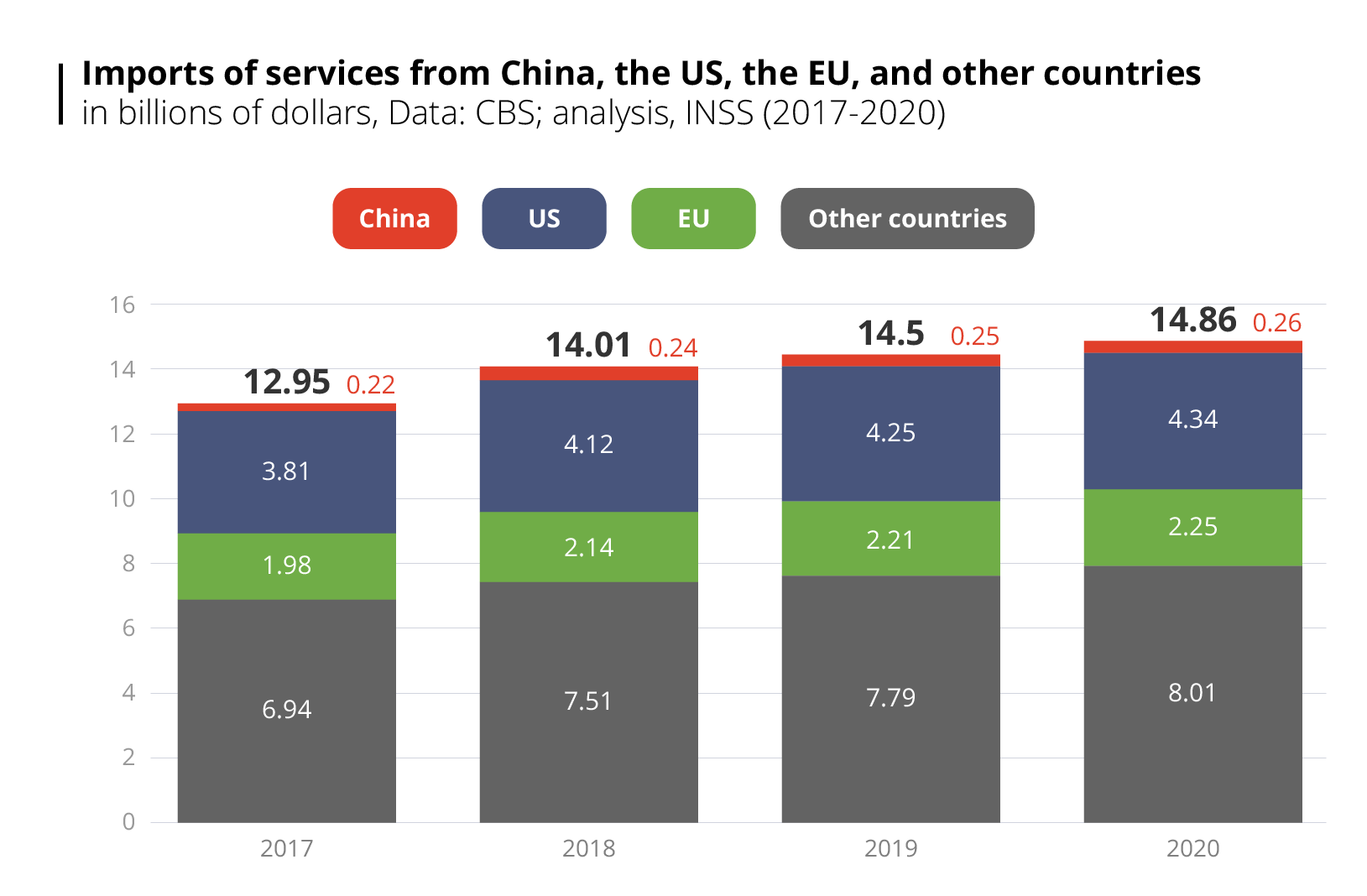

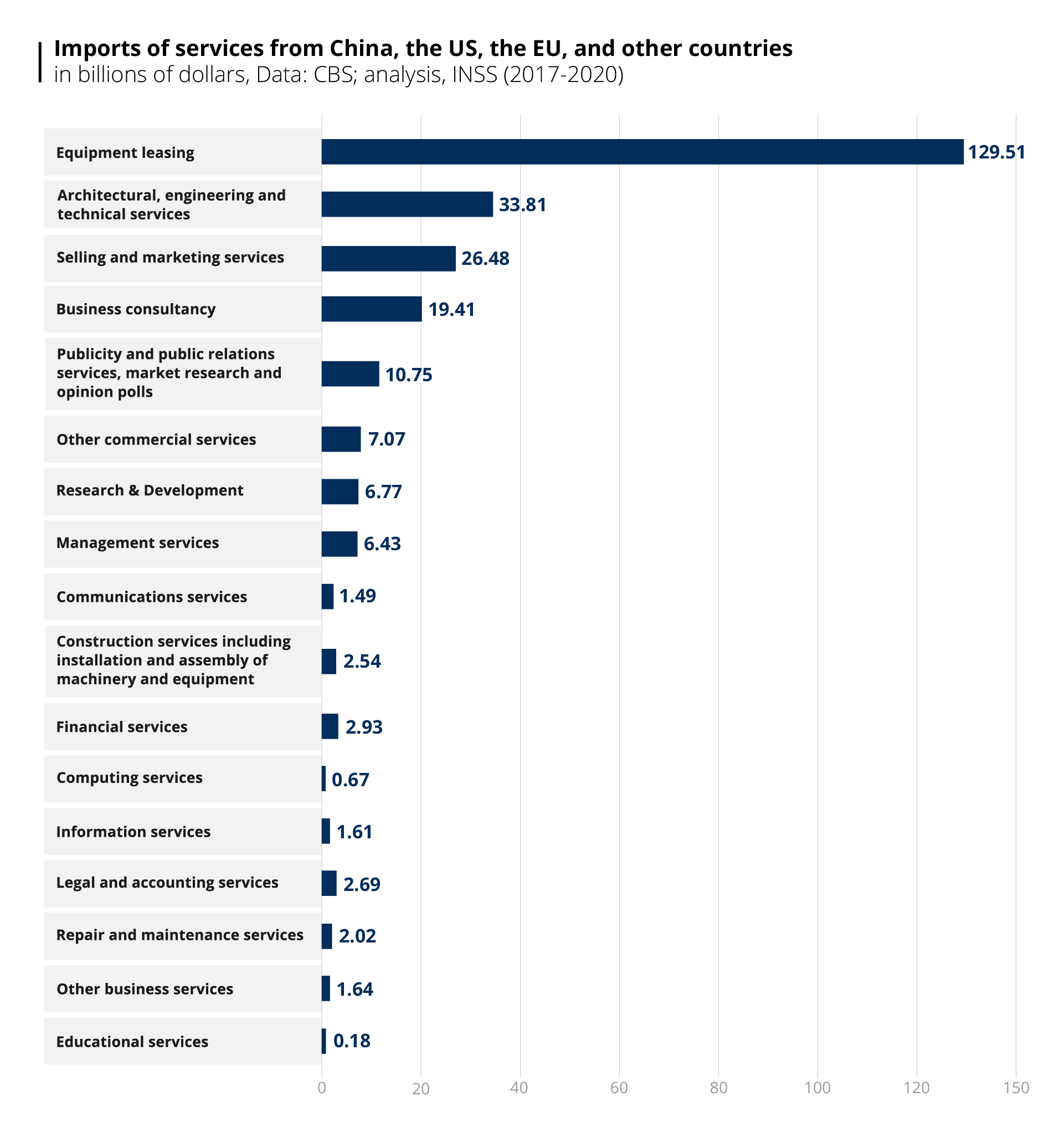

Imports of services from China from 2017 to 2020 constituted on average 1.73 percent of all Israel’s global service imports. Meanwhile, service imports from the United States amounted on average to 29.3 percent of all imports, and on average 15.2 percent from the European Union. There are signs of a gradual but slow increase in service imports, and in 2020 imports of services from China totaled $255.98 million (compared to $4.3 billion from the United States and $2.2 billion from the European Union, Figure 9). In 2020 about 50.59 percent of imports of services from China to Israel were for leasing of equipment ($129.51 million) and about 13.21 percent were for architectural, engineering, and technical services ($33.81 million, Figure 10). China’s involvement in investment and construction of infrastructure in Israel (such as the Tel Aviv Light Railway and the ports of Haifa and Ashdod) can explain these imports, since the companies engaged in building infrastructures hire the heavy equipment required and employ, inter alia, Chinese engineers and technicians, and train Israelis to work on the cranes and other engineering equipment.

Figure 9: Imports of services from China, the US, the EU, and other countries, in billions of dollars (2017-2020) | Source: CBS, analysis, INSS

Figure 10: Service imports from China in 2020 by type of service (millions of dollars) | Source: CBS; analysis, INSS

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

In 2020 and 2021 Israel experienced four significant outbreaks of COVID-19, three of which were met with a general lockdown and widespread restrictions on economic activity. Israel’s international trade was also affected by the crisis, and as the data show, trade in goods with the United States and the European Union, Israel’s two largest trading partners, was considerably reduced (compared to trade in services, which continued to grow). Apart from the first wave, when trade in China declined slightly, trade between Israel and China, in both goods and services, actually increased, particularly during the second and third waves – in which the Israeli economy was closed to varying degrees – and afterwards, and continued to grow in the first half of 2021. However, Israel has an ongoing trade deficit with China (in both goods and services), and in 2020 imports from China increased while exports to China decreased, thereby widening the deficit.

The composition of Israeli goods exported to China is not diverse and relies primarily on the export of electronic components (mainly chips made by Intel). Israel should try to diversity the goods it exports to China and increase its share of exports of goods in branches with real potential for growth due to growing demand in China, such as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, medical devices, and agricultural products. A quick review of the areas where Chinese companies invest in Israel can give an indication of the types of demand in the Chinese market – which is largely focused on purchases of technology-rich products. A previous study by the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) found that in recent years there has been a rise in investments by Chinese companies in the fields of life sciences, clean technologies, and IT and software companies.

Israel would do well to promote exports of various products in the fields of life sciences, such as advanced medical devices, medicines, and technological medical solutions, as well as the export of clean and “green” technologies that are developed in Israel. However, Israel’s trade in services with China is very limited and its potential far from realized, particularly given the increasing demands in the large and growing Chinese market. Israel, as a developed service economy, can create added value for Chinese markets, particularly in the hi-tech sector, and it should therefore employ various means to promote exports of its services to China and thus further diversify the exports of Israeli services worldwide (while in a cautious, measured fashion that will not lead to the loss of intellectual capital).

Given the extent of trade in goods and services with China, Israel at present does not significantly depend on trade with China, which, in spite of being Israel’s third largest trading partner, lags far behind the European Union and the United States (trade in goods with China accounts for less than 11 percent of Israel’s total global trade). However, the gap between the size of Israel’s goods trade with the United States and with China has somewhat narrowed in recent years, mainly due to the increase in imports from China, and in spite of the relative freeze on Israeli exports, particularly during the COVID-19 period. While trade between Israel and the United States declined slightly in 2019 and 2020, trade between Israel and China has increased steadily – a trend that continued during the pandemic.

As an economic superpower, it is important to develop economic ties with China, realize opportunities that the Chinese market offers Israeli businesses, and maximize the economic benefit for the Israeli market in wide-ranging trade relations with China. However, Israel must ensure that it does not develop deep dependency on goods and services imported from China (such as heavy engineering equipment used for the construction of infrastructure), or on the export of certain goods to China (such as chips and electronic components). Such economic dependency could be problematic given a number of trends emerging in China, such as its desire to achieve independent development and local production of chips and semiconductors, or stricter regulation with regard to Chinese global investments and transfer of capital out of the country. International processes could also have a negative impact on China’s trade relations with Israel, such as the growing tension between China and the United States and their struggle for economic and technological superiority in the international arena. The recent deterioration of relations between Australia and China provides a glimpse of how China uses economic leverage and the profound commercial dependence of countries on its markets. When Australia banned the use of the technologies of the Chinese telecoms corporation Huawei in the construction of its 5G network and demanded an independent investigation into the origins of the coronavirus, China responded by imposing quotas on Australian goods, such as wines, cereals, and recently also coal, causing significant damage to the Australian economy. Therefore Israel must avoid dependencies on China that could later affect decisions in other areas, given concerns of a Chinese response that might severely damage trade relations between the two countries and hurt the Israeli economy.

Finally, and in this context, Israel must pay attention to US concerns over China’s growing involvement in the Israeli economy and should continually review its economic ties with China, to ensure that Beijing is not creating economic and political levers. This subject has become more important given the Chinese government’s campaign against Chinese technology and financial companies, and in view of the collapse of the Evergrande real estate corporation and the difficulties faced by other real estate companies in China. One of the ways of preventing this is to diversity the composition of exports to China and Chinese imports to Israel, insist on the implementation of mutual purchasing agreements, and ensure, as far as possible, that Israel has no sole dependency on strategic goods that pass through the supply chain originating in China.

_____________________

[1] In 2020 exports (excluding diamonds) to the European Union ($10.3 billion) and to the United States ($13.8 billion) constituted over 48 percent of all Israel’s exports, which were worth $50 billion. In 2020, Israel’s total foreign trade amounted to 110.8 billion dollars.

[2] 2009 was an exception, when imports from China fell significantly due to the consequences of the 2008 financial crisis; imports also declined slightly in 2012 and in 2019, but grew considerably in 2020.

[3] Trade with the European Union rose slightly in March 2021 to $3.5 billion ($2.5 billion imports from the EU and $966 million exports to the EU); trade with the US in March 2021 fell slightly to $1.6 billion ($649 million in imports and 1 billion in exports to the US).

[4] Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries Co. Ltd., which is owned by the Chinese government, won the tender to sell cranes for the construction of the Ashdod Port in 2017, while implementation of the obligation began in 2019 and continued in 2020.