Publications

Special Publication, November 4, 2024

As the events of Hamas’s attack against Israel on October 7, 2023, unfolded on the ground and across social media, CyberWell’s monitoring technology quickly began to detect a surge of antisemitic content. In the 25 days following October 7, there was an 86% increase compared to the previous 25 days. Alarmingly, CyberWell’s technology also identified a significant shift in the Arabic discourse, moving from promoting traditional stereotypes of Jews, such as secret cabals controlling the world, to advocating for and justifying direct violence against the Jewish people. In this article, we present our findings and critical recommendations for both social media platforms and governments on how to address the clear danger posed by unchecked Jew-hatred, violent speech, and hateful rhetoric to national security and the safety of minority groups around the globe.

Contributing Authors: CyberWell Research Team, Tal-Or Cohen Montemayor

Introduction

The brutal attacks by the Hamas terrorist organization on October 7, 2023, were marked by a simultaneous onslaught of graphic and violent content uploaded in real time and live streamed across social media platforms. Major platforms were caught woefully unprepared to address the vast volume of content that violated their policies, leaving it accessible for hours or even days. While the horrific imagery and celebration of slaughter that Hamas members themselves uploaded initially garnered widespread condemnation, the narrative soon shifted to one that was deeply antisemitic and violent.

CyberWell’s monitoring technology quickly detected a significant spike in antisemitism across social media platforms in both English and Arabic.[1] Our analysts professionally vetted a wide range of posts that included glorification of and incitement to violence against Jewish people, dehumanization, hateful stereotypes, the spread of harmful misinformation, and denying that the horrific events even took place—perpetuating the narrative that Jews are liars.

Social media, and the digital space in general, is significantly less regulated than traditional media. This allows for unprecedented freedom of communication, expression, and the rapid spread of narratives. Unfortunately, this space is also widely misused to spread hate speech, misinformation, and calls to violence against individuals and minority groups, including Jews. Although most major social media platforms guarantee a harassment-free user experience for groups with “protected attributes,” they frequently fail to uphold this promise.[2]

In this article, we present several datasets collected and analyzed before and after the events of October 7. We offer initial insights into the shift in antisemitic discourse in Arabic and discuss major enforcement gaps on social media platforms in addressing antisemitism effectively. We also highlight key recommendations that we provided to the platforms in real time, organized into four categories of policy violations as defined by the social media platforms.[3] Our recommendations are designed to assist content review teams in identifying and removing prohibited antisemitic content in the categories of violence, hate speech, terror, and misinformation. Finally, we offer recommendations for governments to better regulate social media platforms to reduce the spread of hate on a larger scale.

Dataset and Methodology

CyberWell’s methodology for identifying antisemitic content involves using technology to monitor digital platforms for specific keywords, using a specialized, proprietary lexicon that aligns with the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism. This definition includes 11 examples, or categories, of antisemitism. Once a piece of content is flagged by CyberWell’s monitoring technology as likely to be antisemitic the verification process involves one or two rounds of human review, which includes labeling content according to the 11 IHRA examples, analyzing platform policy violations, and identifying specific antisemitic tropes or themes that the post promotes, along with any connections to real-world events. For more information about CyberWell’s methodology, please refer to the policy guidelines.

The insights in this article are based on posts flagged as highly likely to be antisemitic as well as focusing on content in Arabic and English that was verified as antisemitic according to the methodology presented above. These datasets mostly focus on content from the five major social media platforms that CyberWell continuously monitors: Facebook, Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, and YouTube.[4]

It is important to note for the broader discussion that the detection of geo-location of social media users when they upload posts is very limited and usually is based on data that the user provides in their bio description. Between September 2023 and March 2024, the geo-location of 9% of the antisemitic posts in Arabic in our dataset was successfully detected. Some of the identified countries, unsurprisingly, have Arabic-speaking populations, such as Egypt, Jordan, and Morocco. However, we also detected Arabic posts originating from Germany, Italy, and the United States. This insight highlights the flow of content and ideas in different languages and locations, underscoring the need for deeper analysis.

Data Insights

Quantitative Increase in Content Highly Likely to Be Antisemitic on Social Media

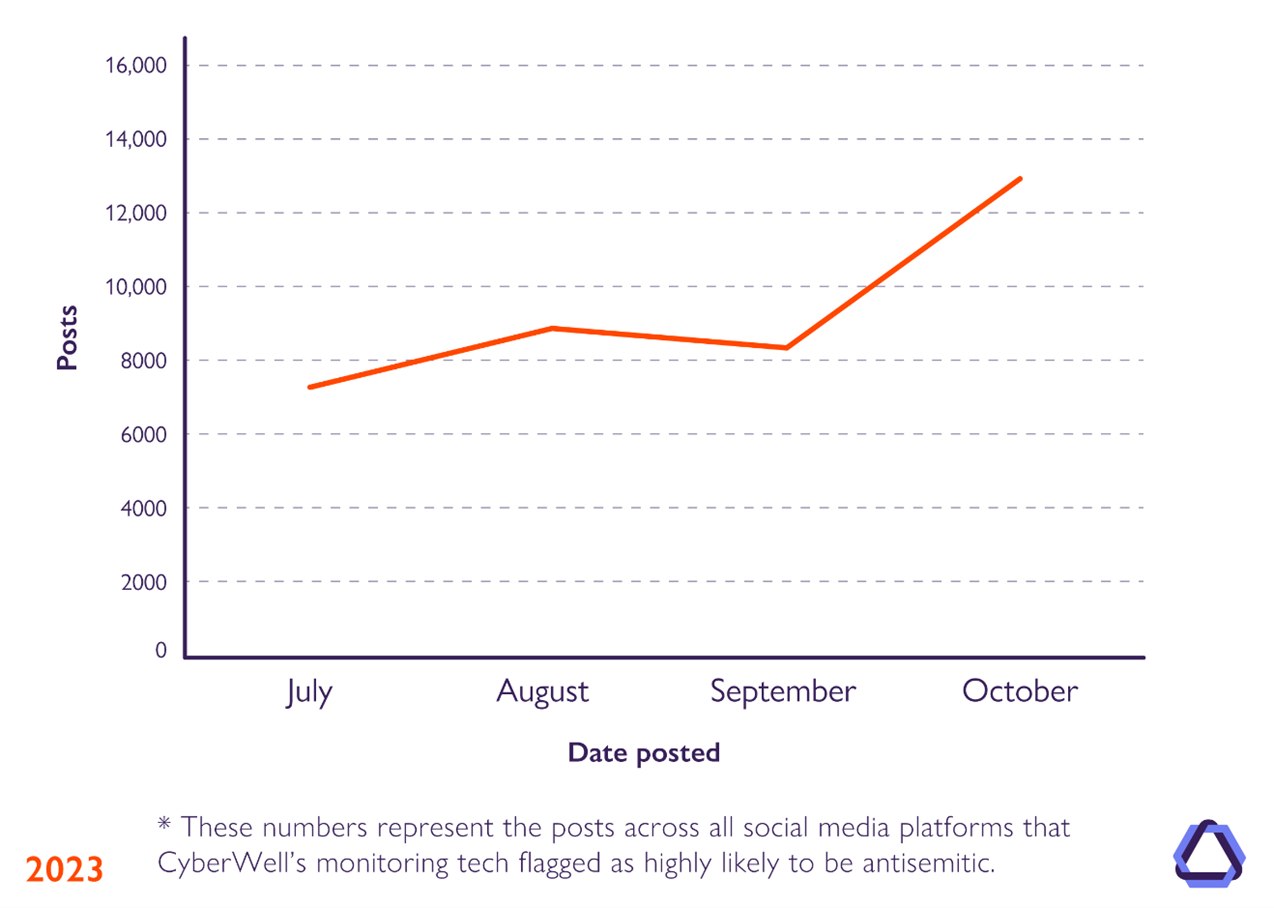

Before delving into the narrative analysis and the shift in the nature of verified antisemitic content since October 7, it is important to present the quantitative increase in content flagged as highly likely to be antisemitic. In the 25 days leading up to the attack on October 7, from September 11 to October 6, a total of 6,959 pieces of content were flagged as highly likely to be antisemitic. Between October 7 and October 31, this number increased to 12,949—a sharp 86% rise in flagged content across the five social media platforms that CyberWell monitors in English and Arabic (Figure 1). Jewish social media users regularly experience a disproportionate amount of targeted hate and harassment, especially during major events involving Israel. This was particularly evident following the October 7 massacre, a violent event that specifically targeted Jews, yet caused antisemitic discourse to skyrocket.

Figure 1. Posts Flagged as Highly Likely to Be Antisemitic by CyberWell’s AI Tech

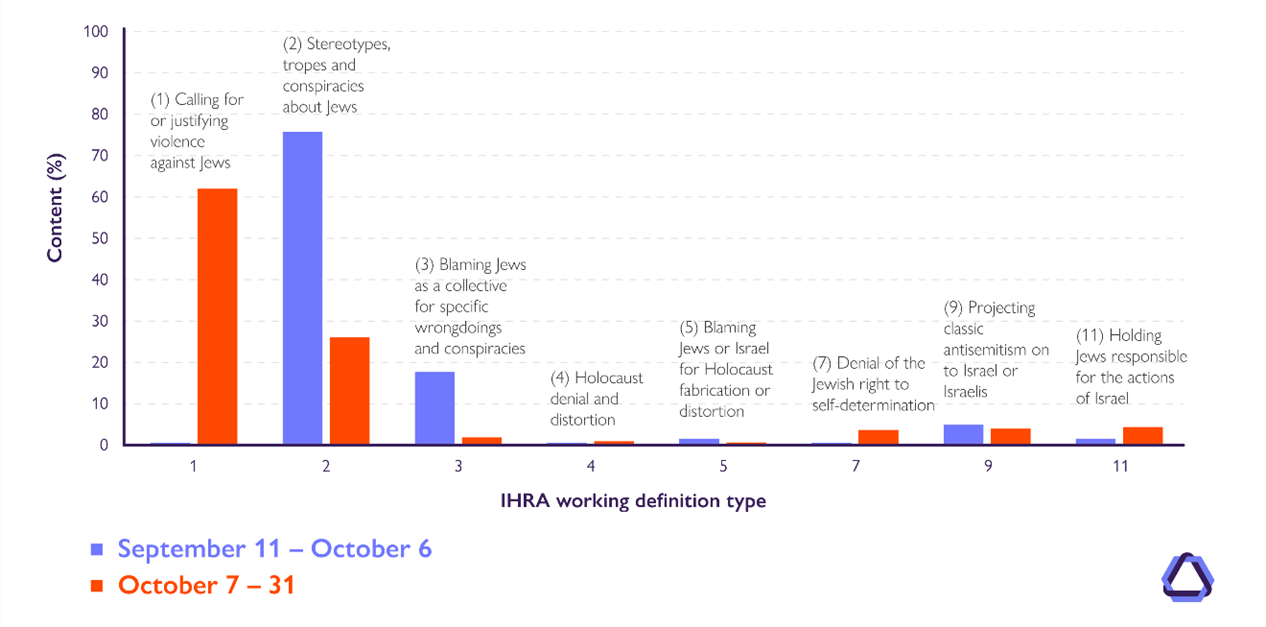

When examining the content of Arabic posts verified as antisemitic during this timeframe, we observed shifts in discourse along two dimensions: the main IHRA examples and the top antisemitic narratives.[5] [6]

Figure 2 shows a clear shift in narrative from IHRA’s type 2 antisemitism (dehumanizing and stereotypical allegations) before October 7 to IHRA type 1 (calling for or justifying violence against Jews) following Hamas’s attack. It also indicates an increase in IHRA type 11, which involves holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of the State of Israel or the IDF. Such allegations directly affect Jewish individuals and communities outside Israel, including those who may not identify with Israel or its policies and actions.

Figure 2. IHRA Breakdown in Arabic Pre- and Post- October 7, 2023

Figure 3 displays three captured images from a TikTok video posted in October 2023. The video calls for a Holocaust against Jews following the war in Gaza and is categorized as antisemitic according to IHRA type 11, holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of the State of Israel, in addition to IHRA type 1, calling for, aiding, or justifying the killing or harming of Jews.

Figure 3. Three Images Captured from a TikTok Video

Note. The captions read, “Where are you, Hitler”; “Gaza is crying out for help.” Both captions are set against a photo of Jerusalem with a Palestinian flag imposed on it. “A Jewish Family 1941” is written on an image of a crematorium.

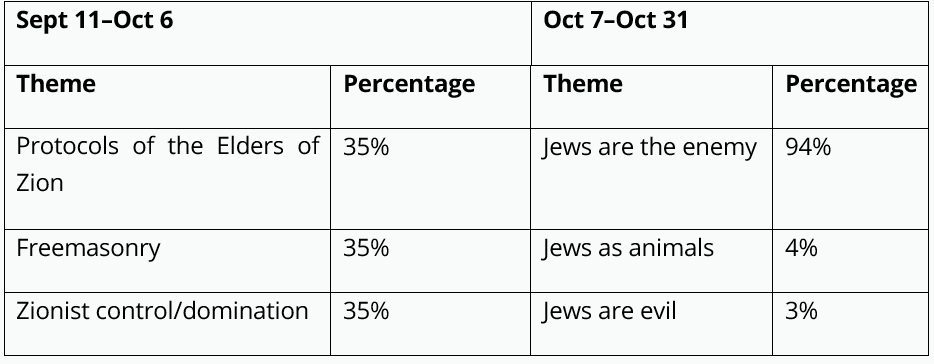

Antisemitic Narrative Shifts in Arabic

By comparing the top antisemitic narratives in the Arabic content within this dataset before and after October 7, we observed an overall shift in discourse (see Figure 4). Prior to October 7, the dominant antisemitic themes focused on conspiracy theories about Jewish ambitions for global domination, including notions of Zionist control,[7] or secretive cabals, as detailed in the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,”[8] along with allegations of Jews infiltrating and controlling the Freemasons.[9] After October 7, the narratives became more hateful and divisive, framed in an “us versus them” tone. This shift included content that dehumanized Jews by likening them to animals such as rats, monkeys, and pigs, [10] portraying Jews collectively as evil, [11] and most prominently, depicting Jews collectively as “the enemy,” sometimes based on religious antisemitism. The percentages represent the proportion of posts in the dataset categorized as promoting the specific tropes, out of the total Arabic posts verified as antisemitic and categorized by CyberWell within the given timeframe. Each post may relate to more than one antisemitic narrative.

Figure 4. Shift in Arabic Discourse Before and After October 7, 2023

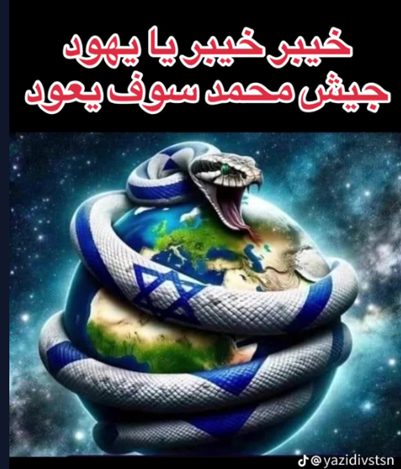

Figure 5 was identified on TikTok after October 7. It depicts an AI-generated image of a snake, with the Israeli flag as its skin coloration, coiled around the world. The caption reads: “Khaybar Khaybar O Jews, Muhammad’s army will return.”[12] The post promotes the narrative that Jews and Israel are an evil enemy while the caption calls for violence against Jews.

Figure 5. Post about Jews and Israel as the Evil Enemy

Note. Taken from TikTok. This post has since been removed.

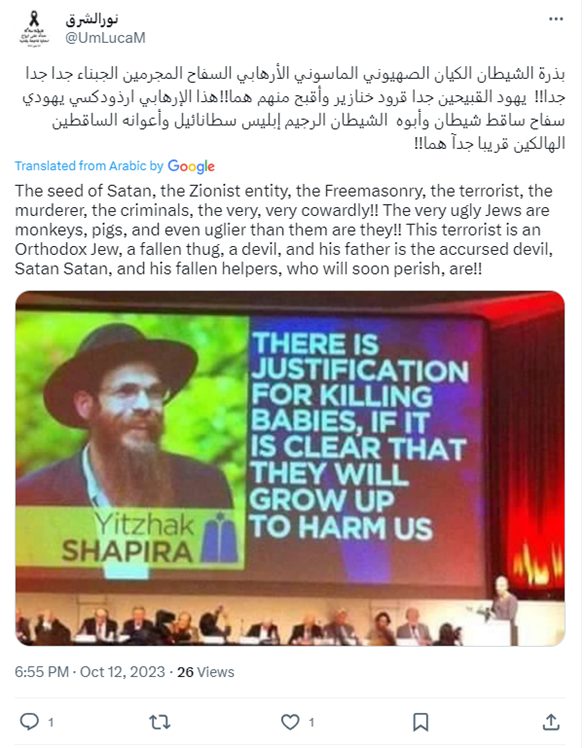

Figure 6 shows a post in Arabic on X (formerly Twitter) that presents several antisemitic conspiracies, including blaming the Jews for various wrongdoings, drawing dehumanizing comparisons to animals, and claiming that Jews are descendants of Satan.

Figure 6. Post Sharing Antisemitic Conspiracy Theories

Note. Taken from @UmLucaM, X (formerly Twitter), October 12, 2023.

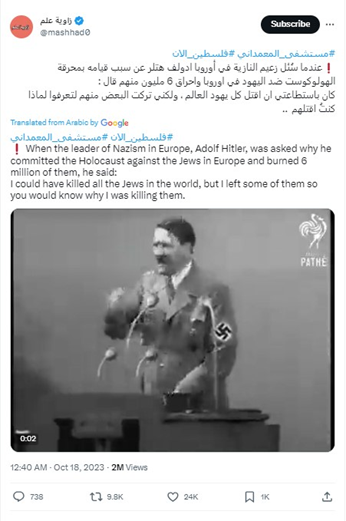

Figure 7 depicts a post in Arabic on X that justifies the Holocaust, posted ten days after the October 7 massacre. It gained over two million views.

Figure 7. Post in Arabic Justifying the Holocaust

Note. Taken from @mashhad, X (formerly Twitter), October 18, 2023.

Global Regulatory Efforts for Online Platforms

A complex network of actors is working to address hate speech on social media platforms at various levels, including policymakers, non-profit organizations, and global brands.

Government Regulation

At the policy level, the implementation of the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) and the United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act now challenge the leniency that platforms previously enjoyed in monitoring and removing hateful content. Following October 7, the European Union, through the DSA, sent letters to Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, warning them of their failure to comply with DSA regulations in removing illegal hate speech—violations that can incur steep penalties of up to 6% of a company’s global revenue in fines.

Social Media Self-Regulation

Social media platforms, to their credit, largely do have clear policies addressing hate speech and the repercussions that users may experience for posting prohibited hateful content.[13] When examining the state of antisemitism across social media platforms, CyberWell identifies and offers recommendations on gaps in both the enforcement of these policies and their handling of complex, nuanced, or modern forms of antisemitism. Across all five social media platforms monitored, our team has identified discrepancies between the written policies and their enforcement in practice. This gap could partially be explained by a lack of investment in content moderation teams. For instance, in the latest DSA transparency report, X (formerly Twitter) asserted that their content moderation team includes just twelve people proficient in Arabic, compared to 2,294 team members proficient in English.

As part of our ongoing methodology, CyberWell assesses the actions taken by the platforms according to their specific policies or strategies. In general, platforms enforce policies against hate speech in two main ways: first, by removing content, and second, by de-amplifying content to limit its visibility. The second methodology is the primary method implemented by X, through their “Freedom of Speech, Not Reach” approach, which emphasizes de-amplification of hate speech rather than its removal. A third step that some social media platforms take is blocking specific hashtags or keywords from being searchable. While this measure does not prevent users from posting content with specific phrases or stop users from passively encountering such content, it does prevent users from actively searching for content tagged with these phrases. More recently, some platforms have begun to include notes when users search for controversial content. For example, when searching for the Protocols of the Elders of Zion on YouTube, users now see an item at the top of the search bar including a link to the Wikipedia article and which includes the text, “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is a fabricated text purporting to detail a Jewish plot for global domination.”

Enforcement Gaps

Governmental Regulations

While the efforts of the European Union and United Kingdom to curb online hate speech are commendable, similar legislation is needed in the United States. For too long, Section 230 has granted immunity to social media platforms, absolving them of responsibility for third-party content hosted on their platforms. CyberWell encourages US policymakers to follow the lead of the European Union and United Kingdom and make amending Section 230 a priority. More can and should be done to bridge the enforcement gaps and protect users from the harmful effects of online hate speech. In addition to amending Section 230, there should be comprehensive regulations mandating social media platforms to implement more effective content moderation strategies and ensure transparency in their enforcement actions, as outlined in the concluding section of this paper.

Platform Regulations

While none of the major social media platforms have formally adopted the IHRA working definition of antisemitism as a policy or incorporated it into their enforcement guidelines, antisemitic statements that align with the various IHRA examples are often prohibited by the platforms’ community standards. As part of our methodology, we examine each piece of content not only for antisemitism but also for any violations of the policies of the specific platform on which it was posted, as well as the enforcement of the platform’s community guidelines. Since our inception, CyberWell has identified and continues to track two overarching language-based enforcement gaps across platforms.

Macro Enforcement Gap 1: Removal Rate of Arabic vs. English Content

One of the first insights that CyberWell shared with social media platforms was the stark difference in the rate of removal of violating content in English versus Arabic. According to a review performed in September 2023, the cross-platform removal rate of reported policy-violating content was 24% in English, while the percentage dropped to 13% in Arabic. We called on platforms to address this gap, and as of a subsequent review in March 2024, the situation has improved. In June 2024, the rates of removal across platforms increased to 29% for policy-violating content in English and 21% for Arabic. Efforts made by these platforms to increase moderation in Arabic are commendable. These efforts should be encouraged to continue, with the goal of closing the language gap and enhancing removal rates for violating content in all languages, both in times of conflict and peace.

Macro Enforcement Gap 2: Moderator Action on Similar Phrases

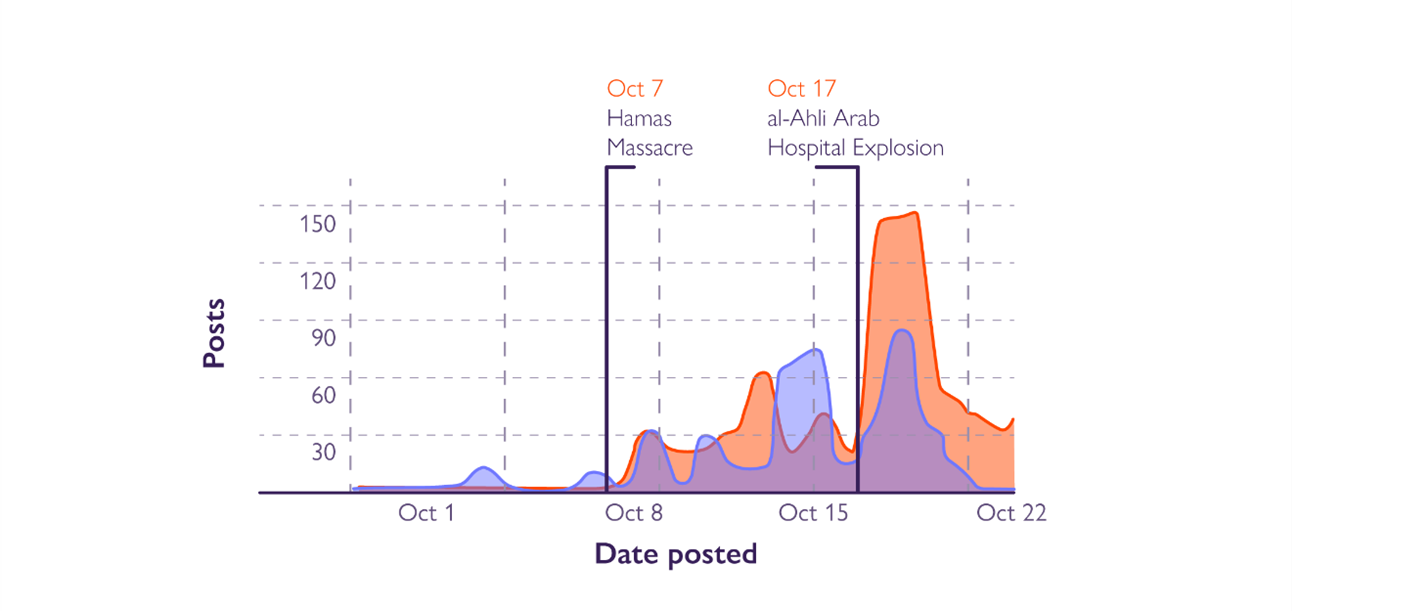

The action taken—or lack thereof—by platforms regarding content with similar phrases in Arabic versus English reveals a stark discrepancy. This moderation gap can be illustrated by the phrase “Hitler was right” in both English and Arabic. Two spikes in the use of this phrase were detected in both English and Arabic across the digital space following Hamas’s attack on October 7 and the subsequent explosion at the al-Ahli hospital in Gaza on October 17, which claimed many lives.[14] In English, the phrase gained popularity as the hashtag #hitlerwasright, with a potential reach of over 25 million social media users in the 18 days following October 7.[15] In Arabic, the phrase spiked as a combination of words rather than a hashtag, reaching a potential audience of nearly half a million users within the same timeframe.

Figure 8. Online spikes of the hashtag #HitlerWasRight in English and Arabic

Figure Guide. Periwinkle indicates English; orange indicates Arabic.

The monitored phrase in Arabic is “هتلر كان على حق”.

Note. The numbers of posts are based on a sample of posts with high engagement rates, mapped by social listening tools.

The hashtag #hitlerwasright previously spiked following the rapper Ye’s (formerly Kanye West) antisemitic statements in October 2022. Following CyberWell’s report on antisemitism in reaction to or in defense of Ye’s antisemitic statements, our tools observed a 91% drop in the use of this hashtag on X, indicating that it had been de-amplified, although not removed.

After October 7, CyberWell alerted social media platforms to the resurgence of this phrase, causing the hashtag in English to be blocked from being searched on X; however, no steps were taken to block the same phrase in Arabic.[16] This indicates that content moderators recognized the phrase as violating platform policy but took action only in one language, despite our recommendation to address it in both languages.

Although X generally prefers de-amplification[17] over removal, the identical violent, policy-violating phrase reached a potential audience of half a million Arabic-speaking users. Despite the larger reach of the English hashtag, the Arabic version should have received, at minimum, the same level of enforcement. The significant potential reach of such a small sample of posts explicitly inciting violence against Jews and promoting Holocaust hate speech calls into question the effectiveness of the “Freedom of Speech, not Freedom of Reach” approach.[18]

Specific Enforcement Gap 1: Violence

Example 1: “PUBG the Jews.” In 2020, Mahmoud al-Hasanat, a Palestinian preacher and writer, [19] delivered a notorious sermon (see Figure 9) in which he stated: “They say this generation is the PUBG generation, right? But open the borders for them, and by God, they will make PUBG with the Jews.”[20] Here, “PUBG” refers to the video game PUBG: Battlegrounds, a violent first-person shooter game[21] where players parachute onto an island, collect weapons, and shoot people. Following the October 7 massacre, the sermon went viral, with users editing this specific part and overlaying the audio clip with videos of Hamas paragliders infiltrating Israeli territory, as they did on October 7; clips from the PUBG game depicting simulated shooting; and videos displaying weapons.

Figure 9. Screengrab from the video sermon of Mahmoud al-Hasanat

Note. Taken from @lamia_g5k, X (formerly Twitter), October 13, 2023.

According to CyberWell’s analysis, the combination of the Arabic terms “ببجي” [PUBG] AND “يهود” [Jews] or images of armed terrorists/gliders is highly likely to include violent content that calls for harm against Jewish people. Between October 7 and 29, this phrase had a potential reach of 53,800 according to social listening tools that CyberWell employs. Social media platforms initially failed to recognize this clear call to violence and allowed these posts to remain online. Following CyberWell’s alert, which included practical recommendations, a significant number of videos featuring this trend were removed from TikTok.

Example 2: “Khaybar, Khaybar.” The chant “Khaybar, Khaybar, oh Jews, the army of Muhammad will return” refers to the battles that the prophet Muhammad fought against specific Jewish communities during the 7th century CE. Since these battles resulted in the mass slaughter of Jews, using this slogan today, especially alongside images of armed individuals, represents incitement to violence against Jews as a collective.[22] Between October 7 and November 30, this slogan in Arabic gained a potential reach of over 596 million users, compared to 1.8 million in the two months before October 7.

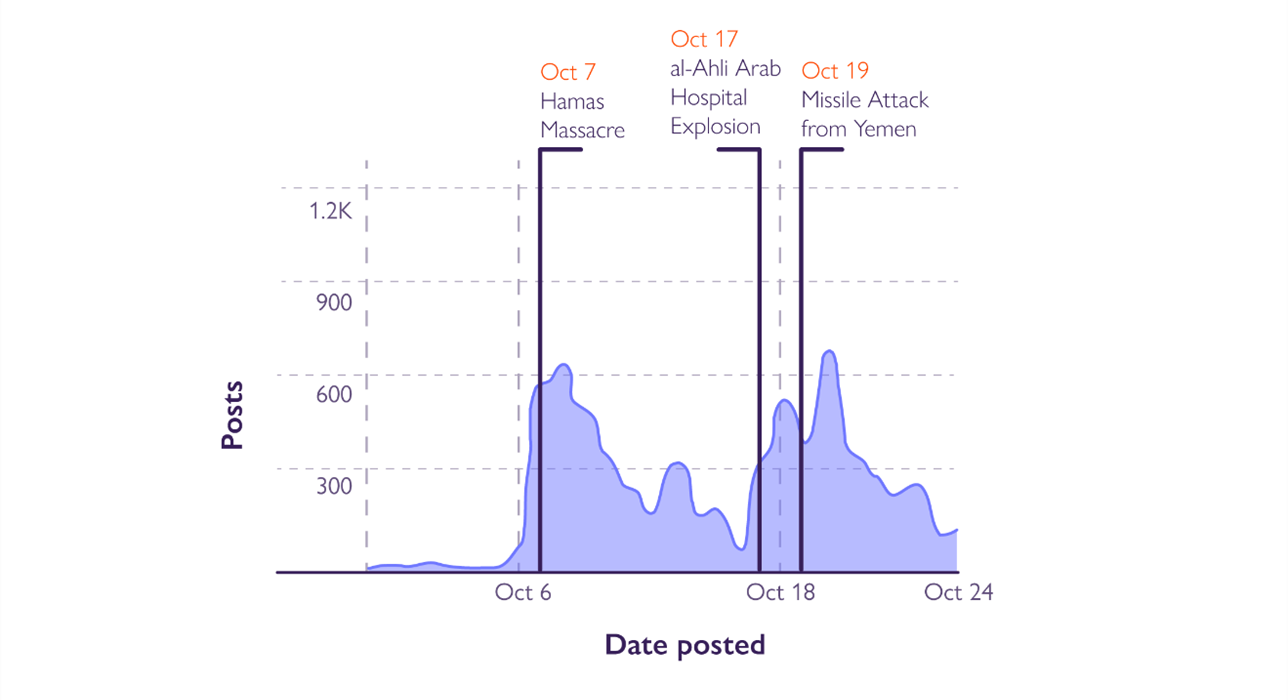

Example 3: Houthi Slogan. Another religious-based slogan that frequently incites violence against Jews is the slogan “Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse on the Jews, Victory to Islam” by the Houthis, who were recognized as a terror organization by the US State Department in early 2024. A sharp increase in the use of this hateful and violent slogan in Arabic was detected after October 7, prior to the missile attack by the Houthis (see Figure 10),[23] and from September 24 to October 24, it had a potential reach of 6 million social media users. This phrase should be closely monitored as it frequently serves as a call to incite violence. CyberWell has submitted recommendations to social media platforms on this issue.

Figure 10. The Houthi slogan “Death to America, death to Israel, curse on the Jews, victory to Islam” online popularity

Specific Enforcement Gap 2: Hate Speech

This analysis identifies two major antisemitic tropes that violate social media platforms’ hate speech policies:

- Portraying Jews collectively as an enemy

- Comparing Jews to animals (for example, rats, pigs, monkeys, dogs)—a form of dehumanization prohibited on all major social media platforms.

CyberWell recommends that platforms closely monitor the combination of the Arabic terms “يهود” (Jews) together with “عدو” (enemy) as highly likely to violate policies. We further suggest that platforms monitor for the use of the Arabic terms “قرود, خنازير, كلاب” (monkeys, pigs, dogs) together with “يهود” (Jews) in both English and Arabic. This content is highly likely to violate hate-speech policies and should be removed at scale.

Specific Enforcement Gap 3: Support for Terror

In addition to providing guidance on antisemitic content, CyberWell began monitoring and offering recommendations on related topics, such as the support and glorification of terrorism, following October 7. Some actions CyberWell recommended to social media content moderation teams include:

- Closely monitor combinations of the names of dangerous organizations,[24] such as Hamas, with various forms of praise. For example, words like “بطل” (hero) or “شهيد” (shaheed, meaning martyr( should not be monitored in isolation but should be flagged when used in reference to a specific organization, terrorist attack, or affiliated individual.[25]

- Monitor hashtags and direct references to terrorist organizations or terrorist attacks. This includes monitoring the hashtag طوفان_الاقصى# (#Al-Aqsa Storm) together with “يهود” (Jews) as well as direct references, such as #القسام (#al-Qassam).[26] Monitoring and mapping these trending combinations in real time help social media platforms address these moderation gaps as quickly and effectively as possible.

Specific Enforcement Gap 4: Denial of a Violent Event as a Form of Antisemitic Misinformation

Disinformation and misinformation played significant roles in sowing chaos, creating an atmosphere of distrust and hate, and shaping global perceptions as the events of October 7 unfolded. CyberWell currently focuses on monitoring and analyzing one specific type of misinformation related to October 7—denial that the massacre and the violent events perpetrated by Hamas, which were extensively documented by the terrorists themselves, took place.[27] This denial not only provides political justification for further attacks by Hamas but also serves as a clear expression of antisemitism. It draws significant parallels to the evolution of Holocaust denial discourse, including attempts to justify the massacre.

In addition to the broader theme of denying that Hamas terrorists perpetrated violence against Israeli civilians—presented in both English and Arabic—three main sub-narratives of denial and distortion have been identified: 1) denying that any acts of sexual assault and/or rape occurred, 2) claiming that violent events did happen but were orchestrated by the State of Israel, and 3) alleging that Israel and the Jews are lying about the violence and profiting from the massacre.

It is important to note that all major social media platforms have specific policies against Holocaust denial, and most also have policies against denying the fact or scope of well-documented violent events in general. Additionally, these platforms have various policies in place to address disinformation and misinformation, though these policies vary by platform.

Our dataset on October 7 denial comprises just over 300 posts collected across five platforms, which collectively garnered over 25 million views. After being reported directly to the platforms, only 6% of the content was removed as of March 2024. The low removal rate reveals major gaps in either the enforcement of platform policies or in the platforms’ failure to include the October 7 massacre as a “recognized violent event.” Social media platforms must recognize the denial of the events of October 7 as policy-violating content and ensure its removal at scale.[28]

Conclusions

Following the events of October 7, several key observations emerged. First, the number of posts in English and Arabic flagged as highly likely to be antisemitic skyrocketed, demonstrating an overall spike in antisemitic rhetoric (see Figure 1). Second, among the Arabic posts confirmed as antisemitic, there was a noticeable shift from narratives that perpetuated general stereotypes of Jews to more violent discourse against Jewish people (see Figures 2 and 3). Third, there was a significant increase in Arabic posts blaming Jews as a whole for the actions of the State of Israel and the IDF (see Figures 2 and 3). While this shift may have been predictable, it imposes collective responsibility on Jews as a group, putting Jewish communities globally at risk.

Finally, social media platforms were woefully unprepared for this surge. In the days and weeks following October 7, content review teams were overwhelmed by the onslaught of violent, graphic, pro-terror, antisemitic, and misleading content. It became glaringly apparent that these platforms had not invested the appropriate resources or developed sufficient infrastructure to manage crises—an issue that has become increasingly evident during other events like the US elections and the spread of COVID-19 disinformation. This case constituted the hijacking of social media platforms by a terrorist organization and their supporters. Consequently, without consistent application of human capital and technology to monitor, flag, and remove harmful content, major social media platforms failed to effectively address the mass mobilization of antisemitic vitriol. This included hashtags, key terms, images, videos, narratives, and pre-existing groups that had been allowed to fester, thereby enabling them to obscure the truth and spread Jew-hatred rapidly.

The normalization of antisemitism on mainstream social media platforms has serious real-world consequences. For instance, conspiracy theories like QAnon have mobilized mobs, leading to the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol. In the weeks and months following October 7, the open celebration of violence against Jews and Israelis highlighted that inadequate infrastructure and investment in content moderation pose a risk to matters of national security. This was further reinforced by the violent takeovers of government buildings, including Capitol Hill, major hubs of transportation, and unlawful encampments on college campuses in the United States. Users who were mobilized online against Israel often echoed calls for violence against Jews, living in echo chambers fueled by social media algorithms that promote engaging content, thus creating a self-perpetuating feedback loop.

This failure to act calls into question the effectiveness of current social media strategies for addressing hate speech and antisemitism, particularly as Hamas demonstrated the ability to exploit these platforms as a tool of psychological warfare by a terrorist group. The inefficacy of content moderation practices was particularly evident in the months following October 7 due to significant gaps in the consistent enforcement of policies, particularly in Arabic. One clear quantitative indication of this enforcement failure is the persistent gap in the removal rates of policy-violating content in Arabic versus English. To address this issue, additional resources must be allocated across the board to bolster the Arabic-speaking content moderation teams.

Policy Recommendations

First, there is a pressing need for improved governmental regulation of social media platforms. In light of the events of October 7, policymakers should consider regulating social media platforms and big tech companies similarly to other heavily supervised public industries, such as banking, pharmaceuticals, or waste management. One recommendation is to require social media platforms to meet a demonstrable threshold of automatic image and audio analysis to prevent the glorification of violence. This would mandate large social media and big tech companies to invest a minimum amount of resources in automated systems designed to prevent the spread of hate and violent content.

Governmental actors at all levels, along with various organizations, can also take action by adopting the IHRA working definition of antisemitism. This definition is the result of over a decade of professional collaborative efforts by international law and policy attorneys, historians, academics, and hate speech experts. It has been adopted by over 40 countries and more than 1,000 organizations and institutions, including state legislatures, municipalities, educational institutions, and sports leagues. By adopting this detailed and nuanced definition, governments and other bodies provide a guiding tool to combat Jew-hatred, extending its influence beyond policy to fields such as research, academia, and emerging realms of new technology.

Second, building on the need for improved moderation strategies, social media platforms should take specific steps to enhance user safety, particularly in light of the October 7 attack. CyberWell has submitted the following recommendations to the social media platforms following these events, focused specifically on content in Arabic:

- Close the enforcement gap between English and non-English languages, especially Arabic, by hiring additional trained content reviewers.

- Apply a more robust approach of automated flagging for hate speech in audio, images, and video content.

- Re-examine policies regarding antisemitism, taking into account the use of religious sources in Arabic.

Ultimately, the role that social media platforms have played in shaping harmful and false narratives, as well as in spreading graphic and violent content that has terrorized the Jewish and Israeli populations, should be of concern to everyone. Antisemitic incidents in the United States were already at historic highs in 2023 before October 7,[29] and they have further increased globally. Platforms have failed in their moral responsibility to protect users due to inadequate infrastructure and inexcusably delayed response times. It is time for these platforms to step up, and for governments and regulatory bodies to impose legal responsibilities to close the gap and prevent our social media platforms from being hijacked by terror groups in the future.

_____________________

** This article is published as part of a joint research project of INSS and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which deals with the perceptions of Jews and Israel in the Arab-Muslim sphere and their effects on the West. For more publications, please see the project page on the INSS website.

[1] CyberWell is a non-profit organization dedicated to eradicating online antisemitism by driving the enforcement and improvement of community standards and hate speech policies across the digital space. Through data, we aim to identify where policies are not being enforced and where they fail to protect Jewish users from harassment and hate. Our professional analysts are trained in the fields of antisemitism, linguistics, and digital policy. As part of our strategy to democratize data, since May 2022, we have been compiling the first-ever open data platform of online antisemitic content.

[2] All five of the major social media platforms that CyberWell monitors protect groups according to “protected attributes.” These include race, ethnicity, gender, religious affiliation, and so forth. For more information, see https://transparency.meta.com/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/; https://www.tiktok.com/community-guidelines/en/safety-civility/; https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2801939?hl=en; https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/x-rules.

[3] For more information on the categorization of policy violations as part of CyberWell’s methodology, see https://cyberwell.org/how-it-works/policy-guidelines/

[4] CyberWell currently serves as a trusted partner for both Meta (the company that owns Facebook, Instagram, and Threads) and TikTok, enabling us to escalate policy-violating content and directly advise content moderation teams. Since October 7, CyberWell has submitted eight reports to Meta, X, and TikTok, with additional information sent to Google.

[5] CyberWell’s monitoring efforts are regularly updated and adjusted according to real-world events. While the comparison is not exact, it does provide an indication of a shift in overall discourse.

[6] For more information about the IHRA working definition, see International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, “Working Definition of Antisemitism,” https://holocaustremembrance.com/resources/working-definition-antisemitism.

[7] One of the most common antisemitic conspiracy theories claims that Jews work toward world domination by taking over the economy, media, and governments. In this context, it is crucial to note that both online and offline, the term “Zionist” is often used as an alternative to “Jew” or “Jewish people” to evade detection by social media platform moderators and avoid international criticism. By avoiding the direct use of the word “Jew,” antisemitic posts can slip under the radar and remain online, despite violating community standards and hate speech policies.

[8] The “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” (the Protocols) is a fabricated antisemitic document that alleges a Jewish plot to take over the world. Written from the perspective of a secret Jewish cabal, it lays out plans to achieve world domination. It is believed that the Protocols were written in the early 20th century in the Russian Empire, prior to a particularly violent series of anti-Jewish pogroms that occurred from 1903 to 1906. Despite having been proven to be a fraudulent document aimed at inciting Jew-hatred, the text continues to serve as a basis for numerous antisemitic conspiracies, including Nazi propaganda. For more on how the Protocols have been used to blame Jews for real-world events, see CyberWell, “World Cup 2022: Sports Uniting Peoples or a Perfect Storm of Antisemitism?” blog, January 10, 2023, https://cyberwell.org/post/world-cup-2022-sports-uniting-peoples-or-a-perfect-storm-of-antisemitism.

[9] Freemasonry in its modern form was officially established on June 24, 1717, when several smaller lodges came together to form the first Grand Lodge in London. Today, Freemason lodges can be found across the globe. Known for its hierarchical structure and secrecy, Freemasonry is a favorite subject of conspiracy theorists, with its followers sometimes portrayed as evil and plotting to rule the world. An offshoot of these theories is the Judeo-Masonic Conspiracy Theory, which accuses the Jewish people of infiltrating the Freemasons to further an alleged goal of global domination, perpetuating a classic antisemitic stereotype. Interestingly, many lodges refused to accept Jewish members for over 200 years. See CyberWell, “The Judeo-Masonic Conspiracy Theory on Meta,” Report, June 2023, https://cyberwell.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Report-Freemasons-Public.pdf .

[10] The reference to Jews or “people of the book” as apes and pigs originates from several Quranic verses (for example, 5:59–60) and hadiths and is widely used in a controversial interpretation within Islamist discourse. See Ofir Winter, Peace in the Name of Allah: Islamic Discourses on Treaties with Israel (De Gruyter, 2022), 120; Neil J. Kressel, ‘The Sons of Pigs and Apes’: Muslim Antisemitism and the Conspiracy of Silence, (Potomac Books, 2012), 23–27.

[11]“Jews are evil” is one of the most prominent antisemitic narratives. This narrative takes various forms but typically focuses on allegedly inherited characteristics and promotes the notion that Jews are inherently evil.

[12] The chant “Khaybar, Khaybar, oh Jews, the army of Muhammad will return” refers to the battles that the prophet Muhammad fought against specific Jewish communities during the 7th century CE, which resulted in the mass slaughter of Jews. See more on the usage of this chant under “Specific Enforcement Gap 1, Example 2”.

[13] While antisemitism is considered a form of hate speech, antisemitic content on social media can also violate policies related to incitement to violence, harassment, misinformation, and other policy themes.

[14] Based on claims by Hamas and the Gaza Health Ministry, news outlets initially reported the explosion as an Israeli airstrike, which Israel denied. Online, there was an outpouring of rage directed against Israel, with some even calling for and justifying violence not only against Israelis but against Jews everywhere. Several days later, independent experts concluded that the damage was caused by a failed Islamic Jihad missile. See CyberWell, “Fighting Hitler-Inspired Jew-Hatred on the Digital Frontlines,” October 20, 2023, https://cyberwell.org/post/fighting-hitler-based-jew-hatred-on-the-digital-frontlines/; Michael Biesecker, “New AP Analysis of Last Month’s Deadly Gaza Hospital Explosion Rules Out Widely Cited Video,” November 22, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/israel-palestinians-hamas-war-hospital-rocket-gaza-e0fa550faa4678f024797b72132452e3.

[15] “Potential reach” of keywords or phrases is calculated using our social listening tools, which track forums and some social media platforms based on a sample of posts with high engagement. These numbers indicate pattern shifts but are not absolute.

[16] The differing approaches by social media platforms to hashtags versus phrases that promote the same content were evident in the case of the hateful hashtag #thenoticing. Following CyberWell’s repeated alerts regarding the disturbing content and scope of this phrase, X and Meta both blocked the hashtag from being searchable but did not block the phase when used as a combination of words. The phrase continues to spread antisemitic and racist conspiracies. The hashtag #thenoticing calls for the public to “wake up” to the “truth.” This “truth” involves various conspiracy theories about Jewish people infiltrating key global leadership positions to achieve world domination, a classic antisemitic conspiracy with a modern take. See CyberWell, “Jewish People Take the Blame for Violent Protests in France,” July 17, 2023, https://cyberwell.org/post/jewish-people-take-the-blame-for-violent-protests-in-france/.

[17] De-amplification is a form of enforcement used by social media platforms to reduce the visibility of posts without outright removing them. When a post is de-amplified, it remains on the platform, but its reach is significantly limited. This means that fewer users will encounter the content in their feeds, search results, or recommendation algorithms. Essentially, the platform minimizes the potential for the post to spread widely while still allowing it to exist.

[18] “Freedom of Speech, not Freedom of Reach” policy, introduced by Twitter (now X), is centered on allowing users to express themselves freely while limiting the amplification of harmful or policy-violating content. For more information see https://blog.x.com/en_us/topics/product/2023/freedom-of-speech-not-reach-an-update-on-our-enforcement-philosophy.

[19] Born in the Jabalia refugee camp in 1989, Mahmoud Salman Jibril al-Hasanat grew up in Gaza and now resides in Turkey. He is a prominent influencer in the Arab world, initially gaining fame on YouTube and later expanding to most social media platforms. His content often features sermons on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, some of which include serious antisemitic remarks and express support for terrorism or terrorist organizations. CyberWell has been monitoring al-Hasanat since the beginning of the Israel–Hamas war, and the followers of his social media accounts continue to grow rapidly.

[20] The original post with the sermon has been removed from al-Hasanat’s official accounts, but the video of the sermon has been widely posted by other users. See, for example, Figure 9, a screen shot from a post 1, X (formerly Twitter), October 13, 2023.

[21] “A first-person game” refers to a type of video game where the player experiences the game world through the eyes of the protagonist or playable character.

[22] For a comprehensive report on this point, see CyberWell, “Jenin, Jew-Hatred, and Incitement to Violence on Social Media,” July 7, 2023, https://cyberwell.org/post/jenin-jew-hatred-and-incitement-to-violence-on-social-media/.

[23] The Yemen-based Houthi terror group launched several missile and drone attacks toward Israel and the Red Sea as an act of solidarity and support for Hamas in Gaza. Figure 10 refers to the missile attack launched on October 19, 2023. See Maha El Dahan, “Who Are Yemen’s Houthis and Why Did They Attack Israel,” Reuters, November 1, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/who-are-yemens-houthis-why-did-they-attack-israel-2023-11-01/

[24] Each platform defines its list of organizations and individuals considered dangerous based on external references, typically the US State Department or other points of reference. For example, see Meta’s policy on dangerous individuals and organizations, https://transparency.meta.com/policies/community-standards/dangerous-individuals-organizations/

[25] It is highly likely that, when the term “شهيد” is used to refer to a terrorist who has died, it is being used to praise and glorify their violent actions. CyberWell monitors the use of the term specifically when it glorifies the death of individuals who have committed violent acts. Many Muslim traditions describe the reward awaiting a “shahid,” including ascending directly to Paradise, forgiveness of all sins, and a crown of glory being placed on their heads. Earlier this year, CyberWell submitted a policy advisory opinion on this issue to Meta’s independent Oversight Board.

[26] This is in reference to the al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of Hamas.

[27] CyberWell, “Denial of the October 7 Massacre on Social Media Platforms,” Antisemitism Trend Alert, https://cyberwell.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Denial-of-October-7-Social-Media-Trend-Alert-CyberWell.pdf.

[28] Since the writing of this article, TikTok has publicly recognized the denial of sexual assault on October 7 as prohibited content. Rates of removal have increased accordingly, demonstrating that clear policies lead to concrete action.

[29] ADL, “Audit of Antisemitic Incidents 2023,” April 16, 2024, https://www.adl.org/resources/report/audit-antisemitic-incidents-2023.