Publications

Special Publication, November 1, 2021

The four agreements and declarations achieved in 2020 between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan, respectively, represent a breakthrough in the regional peace process, and perhaps even an opening for other Arab and Muslim countries to join the process of normalization with Israel. This paper assesses the importance of these agreements for Israeli national security in the broadest sense, and recommends a series of measures for enhancing the existing accords and extending normalization to other countries.

Given the relatively short amount of time that has passed since the Abraham Accords were signed – just over a year in the case of the UAE, and Bahrain, and ten months in the case of Morocco and Sudan – any evaluation of the agreements at this stage remains preliminary. Still, developments in the last year permit three overarching observations on their initial significance and their potential future trajectories. First, insofar as the Accords change a decades-old paradigm that had consistently linked prospects for Israeli peace with Arab states to a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the normalization agreements of 2020 reflect a significant improvement for Israel’s strategic position in the region. Second, there remains considerable variation in the extent to which each agreement has translated into policies on the ground; at one end of the spectrum, the agreement between Israel and the United Arab Emirates remains the strongest of the four, while the agreement with Sudan has not yet led to significant changes in bilateral relations. Third, the events surrounding the escalation between Israel and Hamas in May 2021 suggest that while existing normalization survived that critical test, even the most robust agreements are not likely to remain completely impervious to events in the Israeli-Palestinian arena.

Background to the Abraham Accords: Long-Term Interests, Short-Term Triggers, and Initial Reactions

The announcement of normalized relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates on August 13, 2020 surprised many people, even though the agreement capped a years-long process of gradually strengthening links between the countries. On September 15, 2020, the UAE signed a normalization agreement with Israel; that same day, Bahrain signed a declaration of peace with Israel, and one month later the two signed a joint declaration on the establishment of diplomatic relations and a series of memorandums of understanding. On December 22, 2020, Morocco signed a declaration announcing the renewal of diplomatic relations with Israel, in the spirit of the Abraham Accords. After the announcement of normalization of relations between Israel and Sudan in October 2020, a declaration was signed in Khartoum on January 6, 2021, in the presence of the US Secretary of the Treasury.

Behind this flurry of diplomatic activity was a mix of longer-term trends that over the years had brought Israel and the Gulf states into alignment, and a number of proximate triggers linked to the commitment of a particular administration in the White House and concurrent political considerations within Israel throughout the summer of 2020. With respect to the Gulf states, underlying the Abraham Accords were a number of core national security interests, including the common Iranian threat and a shared ally in the United States. The attitude of some Arab countries concerning the Israeli-Palestinian conflict changed over the years, and the Gulf states in particular gradually lowered their demands of Israel as a condition for normalization, effectively abandoning the implied bargain of the Arab Peace Initiative. Recently a number of statements emanating from the Gulf even placed some of the blame for the lack of progress in the Israeli-Palestinian arena on the Palestinians, reflecting a rising frustration among leaders of the Gulf states at perceived Palestinian inflexibility. Israel had developed largely covert ties with several Gulf states (all the while maintaining quiet relations with Morocco) in the security/intelligence and economic/trade realms, and more recently the countries engaged publicly in regional interfaith dialogues partly spearheaded by the UAE.

Even before the normalization agreement was signed, in the Emirates alone the ties with Israel were gradually becoming more open: the Israeli national anthem was played at sports events; there were visits of Israeli ministers; a chief rabbi was appointed for the Jewish community in Dubai; Israel was invited to participate in Expo 2020 (which eventually opened in October 2021); Abu Dhabi sent aid to the West Bank to help it combat COVID-19 (although the aid was rejected by the Palestinian Authority because it was sent via Israel); the UAE ambassador to the United States published an article in an Israeli newspaper; and Israel and the UAE signed a treaty to cooperate in the fight against COVID-19. The Emirates (together with Jordan) headed the Arab camp that openly opposed Israel’s intention to apply its sovereignty in the West Bank, but in retrospect, it seems possible that this was in preparation for normalization.

The more proximate triggers motivating normalization with Israel were connected to the countries’ relations with the United States and what they stood to gain from the Trump administration. In June 2019, at a workshop in Bahrain, the administration described the financial benefits that could derive from the promotion of ties between the participating countries, including Israel. Then in January 2020 President Trump announced his “deal of the century” peace plan, which included stipulations widely seen as endorsing Israeli annexation of parts of the West Bank. By the following summer, a number of core interests had converged to incentivize the agreements.

- The United Arab Emirates had a clear interest in strengthening its ties with the United States and scoring points with the administration, as well as improving its image and status as an influential regional actor. On a practical level, the UAE wanted access to advanced American weapons systems. At home, the agreement with Israel was presented as a diplomatic victory, intended to benefit the Palestinians, and the necessary price of stopping Israel’s intention to impose its sovereignty on the West Bank (based on the Trump framework). According to senior officials, not only was the willingness to accept normalization with Israel not intended to be at the expense of the Palestinians, but its purpose was actually to preserve the relevance of the two-state solution and contribute to stability in the Middle East. Reactions to the move from Emirati citizens on social media, particularly shortly after the announcement of the agreement, were mainly positive – in support of de facto ruler Mohammed Bin Zayed – while most of the criticism on social media came from other countries in the Gulf, namely Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar.

- Bahrain’s interest was first and foremost to fortify its relations with the United States and bolster its security against the Iranian threat, as well as strengthen its economy by means of ties with Israel. It is doubtful the agreement between Israel and Bahrain would have come about without the approval of Saudi Arabia, which has decisive influence on the foreign relations of Bahrain, as well as the UAE. The step taken by the King of Bahrain was in many ways more daring than that of the UAE, in view of Iranian subversion in Bahrain, since the island’s civil society is very active and the Shiite majority opposes the minority Sunni rule. Responses to the agreement among the general Bahraini public – both Sunni and Shiite organizations and opinion leaders – were largely negative.

- For Sudan, normalization with Israel was the price paid for Washington’s decision to remove the country from the State Sponsors of Terrorism list after twenty-seven years, and an accompanying aid package of $1 billion from the World Bank. Thus, Sudan’s overriding interest in agreeing to normalize relations with Israel was economic, insofar as officials in Khartoum presumed the financial relief that would flow from these decisions would help stabilize the country. In the spring of 2019, mass demonstrations led the military to overthrow Sudan’s longtime Islamist autocrat, Omar al-Bashir, and thereafter a transitional government was installed and tasked with preparing the country for elections. Until the coup d’état of October 25, 2021 (the details of which remain murky as of this writing), the transitional government was led by an 11-member Sovereignty Council consisting of civilian and military representatives, and the tensions between the two were evident at the time of the agreement’s announcement: whereas the Chairman of the Sovereignty Council, Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and his deputy, Mohammed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo, were openly supportive of normalization (Burhan even met with then-Prime Minister Netanyahu in February 2020), Abdalla Hamdok, Sudan’s civilian Prime Minister, contended that engaging with Israel would first require a dialogue within Sudanese society.

- In the case of Morocco, normalization with Israel – what Rabat has termed “a resumption of…full diplomatic, peaceful, and friendly relations” – came in exchange for Washington’s dramatic decision to formally recognize Moroccan sovereignty in the Western Sahara. A long-sought aim of the kingdom, American recognition broke with decades of US policy, which had largely endorsed a UN-led, if stalled, process of negotiations between Morocco and the Algerian-backed Polisario movement demanding independence for the territory. The idea of securing American recognition for Moroccan sovereignty in the Sahara in exchange for Rabat’s resumption of ties with Israel had reportedly been circulating for several years, but the ultimate breakthrough nonetheless caught observers by surprise. The controversy surrounding the sovereignty decision was not lost on Rabat, which eschewed the term “normalization” partly to hedge against the possibility that the incoming Biden administration would backtrack on the recognition.

Indeed, with the election of Joe Biden, doubts emerged concerning the viability of all four normalization agreements, given that the new administration – while supportive of improved between Israel and the Arab world – was known to harbor misgivings about the manner in which the agreements were secured. Most troubling from the standpoint of Israel and the Arab states that signed the agreements were questions surrounding the new administration’s commitment to both the arms deal with the UAE and the decision over the Western Sahara. However, both the Emirates weapons deal and the Western Sahara decision have remained in place for now, and Biden administration officials have stated that they intend to push for security cooperation between Israel and the countries that agreed to normalization – although it is not known whether they will invest significant resources for this purpose – in order to promote the process of rapprochement. Thus far a slew of more pressing concerns, from the pandemic to the confrontation with China, have pushed normalization down the list of Washington’s policy priorities.

The Test of Operation Guardian of the Walls

The round of fighting that erupted between Israel and Hamas in May 2021, and particularly the events in Jerusalem that preceded it, comprised the first important test of the strength of the normalization agreements. The UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco criticized Israel for what they called an attack on Palestinian rights and the sanctity of al-Aqsa, reflecting an interest in displaying solidarity with the Palestinians, particularly after having been accused of betrayal when they signed the normalization agreements.

However, the relative calm in Jerusalem after a few days of tension, and the shift in the center of gravity to direct clashes between Israel and Hamas, allowed Israel’s newfound allies to keep a low political profile. Their comments gradually became more balanced, placing responsibility for the escalation on both Israel and Hamas. Along with their basic empathy for the Palestinians and the extensive coverage from Gaza during the fighting, they also reported attacks on Israeli citizens. Columnists in the Arab media, who often reflect the position of the regime, blamed Hamas for the fighting and for the harm caused to the Gaza population, and even expressed some empathy for Israeli citizens forced into shelters by the barrages of rockets and missiles.

Many Arab states, and certainly those that have treaties with Israel, did not want to see Hamas score major gains, as the group is identified with the Muslim Brotherhood and has been linked to Iran. Some hoped, even if they did not say so in public, that Hamas would emerge weakened. Their relatively subdued reaction to the fighting gave Israel time to continue its airstrikes targeting the organization. They also avoided statements on the violence between Jews and Arabs within Israel, and at the height of the campaign in Gaza, the Foreign Minister of the UAE even expressed support for continuation of the normalization process with Israel.

The outbreak of hostilities between Israel and Hamas did temporarily slow the momentum on a number of bilateral Israeli-Emirati and Israeli-Moroccan initiatives, respectively, particularly at the level of civil society. For example, dialogues between research institutes, as well as online engagements aimed at promoting business investment and cooperation between the countries, were postponed upon the request of Emirati and Moroccan participants. Nevertheless, the criticism of Israel, which was focused on events in Jerusalem, did not translate into practical steps such as the recall of ambassadors or cancellation of agreements. Still, as the campaign in Gaza continued, it was harder for the countries to keep to this political line. In view of the extensive damage in the Gaza Strip, the countries gradually evinced stronger support for the Palestinians, although they distinguished between religious and humanitarian support for the Palestinians and the need to continue observing agreements, particularly economic ones, with Israel. Presumably the relatively quick end to the fighting prevented a possible erosion of the agreements.

The one exception to an otherwise largely hostile Arab treatment of Hamas throughout the mini-war came – surprisingly – from Morocco. Following the ceasefire, Moroccan Prime Minister Saad-Eddine El-Othmani, who also heads the country’s main Islamist party in the governing coalition, wrote a letter to Ismail Haniyeh praising the organization’s “victory” over Israel. In June, Haniyeh himself traveled to the kingdom to meet with high-level figures in and out of the government. These developments, while disturbing to the extent that they lent Hamas additional legitimacy, did not reflect a desire on the part of the monarchy to walk back the restoration of ties with Israel, so much as dynamics within Morocco’s domestic political scene, where the Islamist party was eager to burnish its credentials ahead of legislative elections in the fall. Rabat also likely sought to signal to Washington that it could play a mediating role between Israel and the Palestinians. Indeed, on the day Haniyeh landed in Morocco, King Mohammed VI warmly congratulated Prime Minister Bennett on the formation of his government, and by August Foreign Minister Lapid had traveled to the kingdom to formally open the Israeli liaison office.

Morocco’s diplomatic dance with Hamas is a reminder that as long as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not resolved, Arab leaders’ continued need to reinforce their bona fides concerning the Palestinian issue will raise the possibility of uncomfortable diplomatic situations Israel will need to navigate. Moreover, events such as the escalation between Israel and Hamas could give the countries that have chosen to sit on the fence and have so far not joined the Abraham Accords further reason to avoid normalization with Israel. It is possible, for example, that countries such as Saudi Arabia sighed with relief, because their refusal to join the Accords, in spite of heavy pressure from the Trump administration, has, as they see it, saved them unnecessary embarrassment and criticism.

The Agreements to Date

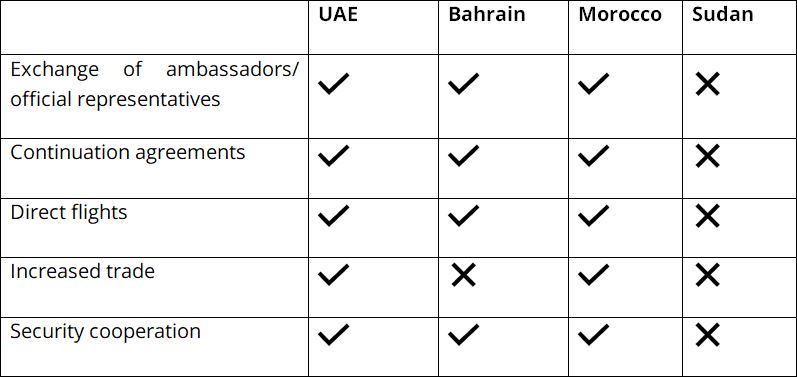

Excepting the Israel-Sudan agreement, which has yet to significantly jumpstart bilateral relations, all of the normalization agreements signed in 2020 have yielded tangible policy outcomes, albeit to varying degrees. The changes are reflected across five indicators: the exchange of ambassadors, follow-on agreements and related MOUs, direct flights, trade, and participation in joint military exercises. The table below offers a comparative look at the progress to date across these indicators, followed by a more detailed account of the policies enacted in each bilateral arena.

Israel and the United Arab Emirates

The importance of relations with the United Arab Emirates is largely diplomatic and economic, since even before the Accords there was some security-political cooperation between the countries, which have a similar view of the strategic environment: both are wary of the ambitions of Iran and Turkey to increase and extend their influence in the region. Relative to the other agreements with Israel, normalization with the UAE is advancing more quickly and bearing fruit, even if mainly economic. The background is linked inter alia to the special features of the federation: a small native population, the lack of active internal opposition, important economic resources, and a ruling elite that is committed to a long-term strategic plan that mandates action, implemented with determination. In this UAE differs from the three other normalization countries, which have security, political, demographic, and ethnic sensitivities that hinder progress.

Since the Abraham Accords were signed, the reported volume of trade between Israel and the Emirates (which is the second largest economy in the Middle East) has reached about half a billion dollars (including diamonds, which accounted for most trade between the countries even before normalization). The normalization agreements have led to a huge growth in foreign trade: according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2019 exports from Israel to the UAE totaled $11 million, and imports were 0, while in 2020 exports amounted to $18 million and imports amounted to $75 million. In the first eight months of 2021, exports from Israel to the UAE reached $68 million, and imports reached $241 million. These figures refer only to trade in reported goods, without diamonds, and do not reflect the services sector, including tourism, and the hi-tech sector.

Data: CBS

Likewise, conditions exist between Israel and the Emirates for establishing a “warmer peace,” certainly in comparison to relations between Israel and Egypt and Jordan, and the countries have signed memorandums of understanding and cooperation agreements in the areas of culture, science, food security, water, and medicine. However, some of the follow-on agreements, such as the Investment Fund announced in March 2021, have been held up for bureaucratic reasons.

The UAE has expressed interest in investment in important areas that are directly linked to Israel’s national security, including the following:

Delek Drilling sold its stake in the Tamar gas field, amounting to 22 percent of the field, to Mubadala Petroleum, owned by the Abu Dhabi government, which invests and manages assets in the field of oil and gas exploration and production worldwide. This is the largest trade agreement between the Emirates and Israel since the signing of the Abraham Accords.

The Trans-Israel Pipeline company signed a binding memorandum of understanding to transport Emirati oil from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea using the existing facilities between Eilat and Ashkelon, although reportedly the deal is currently frozen. Senior Emirati figures have sent messages to Israel that relations could be affected if the deal is canceled.

Israeli shipyards are competing with DP World from Dubai, a global leader in marine logistics and shipping, to acquire Haifa Port, as part of the port’s privatization process.

Israel Aerospace Industries has signed an agreement with Etihad Airlines from Abu Dhabi to set up a facility in Abu Dhabi to convert passenger planes to a cargo configuration.

Israel Aerospace Industries announced cooperation with EDGE, the UAE advanced technologies group, to develop an advanced system against drones and unmanned aircraft.

An Embassy is born!

Israel's new embassy to the United Arab Emirates in Abu Dhabi, inaugurated today by FM @yairlapid, will fortify and further develop 🇮🇱🇦🇪 relations.

FOLLOW the embassy on twitter @IsraelintheUAE & its Head of Mission @AmbassadorNaeh pic.twitter.com/5IY1AnUXFz

— Israel Foreign Ministry (@IsraelMFA) June 29, 2021

Israel and Bahrain

Bahrain’s links to Judaism are the most robust of the states in the Arabian Peninsula. The kingdom has a Jewish community of a few dozen, with a synagogue and a cemetery. The Bahraini Royal House, including King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, is known for their good relations with the Jews, who have not suffered discrimination. Moreover, a Jew by the name of Ibrahim Daoud Nunu served for two terms in the upper house of the Bahraini parliament. One of his relatives, Huda Ezra Nunu, was appointed Bahraini ambassador to the United States (2008-2013). As with the UAE and Morocco, between Israeli and Bahrain there were not inconsiderable contacts before they signed the Abraham Accords, including security contacts, and there are reports that an Israeli representation was active on the island for about a decade under a business camouflage. The Bahraini economy is significantly smaller than that of the UAE, and consequently, so too are the potential economic opportunities of the agreement.

However, relations between the countries have advanced since the Accords were signed. In November 2020 the Bahraini Foreign Minister, Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani, made the first official visit to Israel at the head of a delegation including senior figures from the Foreign Ministry and other ministries. In August 2021, the Deputy Foreign Minister of Bahrain, who is in charge of contacts with Israel, visited Israel, and met with various officials, including President Isaac Herzog and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid, and leading organizations. In March 2021 the Foreign Ministries of Bahrain and Israel announced the kingdom’s decision to open an embassy in Israel, and the first ambassador of Bahrain to Israel, Khaled Yousif Al-Jalahma, arrived in September 2021 for the embassy opening. Before coming, he tweeted in Hebrew: “A chance to realize the vision of His Majesty King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa of peaceful co-existence with all peoples is a privilege that I will fulfill with great esteem.” On September 30, 2021, Foreign Minister Lapid visited Bahrain, the first official visit of an Israeli minister to the kingdom. In Manama, Lapid met his Bahraini counterpart and opened the Israeli embassy, and that same day, the Bahrain national airline Gulf Air began direct flights to and from Israel.

Israel and Morocco

The agreement between Israel and Morocco avoided mention of embassies and ambassadors, noting instead plans to “reopen the liaison offices in Rabat and Tel Aviv,” and to launch direct flights and encourage cooperation in a range of fields, including trade, investment, agriculture, and technology. To a considerable degree, these intentions have translated into concrete policy. In February 2021 Abderrahim Beyyoud, a career diplomat who previously served as Morocco’s Consul General in New York and London, arrived in Israel to take up his post as head of Morocco’s liaison office, which was operational in the 1990s but closed in the early 2000s with the outbreak of the second intifada. The office, located in Tel Aviv, is expected to become the embassy if Rabat decides on an official upgrade of relations. David Govrin, another veteran diplomat, serves as the Israeli envoy to Morocco.

Both Foreign Minister Lapid and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Director General, Alon Ushpiz, visited the kingdom this summer, marking the first such high-level diplomatic visits in over twenty years. Ushpiz’s visit lay the groundwork for a cybersecurity cooperation agreement signed in the ensuing weeks, which calls for joint work in cybersecurity operations, R&D, and data sharing and protection. Lapid’s visit in August yielded an announcement that the countries plan to upgrade relations to full diplomatic ties and open embassies within two months. Indeed, in October Israel upgraded David Govrin’s position to ambassador.

In July, the first direct commercial flights from Israel landed in Marrakesh – one operated by Israir and the second by El Al. Israir plans to offer two to three such flights each week, and El Al operates five weekly flights to Marrakesh and Casablanca. Royal Air Maroc, the Moroccan national airline, is reportedly set to begin direct flights to Israel in mid-November. In mid-October the new government in Morocco announced its intention to ratify the agreements in the fields of culture, sports, and aviation that were signed during Lapid’s visit. Trade between the countries has also increased, although almost entirely in the direction of Israeli exports to Morocco, which grew from $8.1 million in the first half of 2020 to $13.2 million in the first half of 2021. (Imports from Morocco hardly changed, rising from about $5.5 million to $5.9 million in the same period.) These figures, which do not include services relating to tourism, are not significant in absolute terms, although the trend is positive. Finally, while Israel and Morocco have reportedly cooperated on military and security matters in secret for decades, this past June, Moroccan special forces, for the first time, openly participated in an international military exercise held in Israel, alongside special forces from Greece, the US, Italy, Jordan, the UK, and France. Defense Minister Benny Gantz is reportedly due to visit Morocco in the coming weeks to draw up a number of agreements in the area of security.

Israel and Sudan

The agreement between Israel and Sudan has not produced significant results, although a number of recent developments suggested the momentum was increasing. In January 2021, an Israeli delegation headed by Minister of Intelligence Eli Cohen went to Khartoum to meet with Gen. al-Burhan and other senior security officials, and the outcome was a memorandum of understanding on security-related matters whose details not been publicized. Minister Cohen invited senior Sudanese officials to visit Israel, and in April 2021 the Sudanese cabinet voted to abolish a law dating from 1958 which bans contacts with Israel, and thus effectively allowed Sudanese citizens to conduct business with Israelis. Thus far no ambassadors have been exchanged.

In September, a year after the Abraham Accords were signed, the former head of the National Security Council, Meir Ben Shabat, said that a great deal of work remains with respect to Sudan and that “we haven’t progressed as much as we wanted to,” although as he put it, conditions were “ripe” for the signing of agreements. In early October reports surfaced that a Sudanese security delegation had visited Israel, and on October 13, Deputy Foreign Minister Idan Roll and Minister for Regional Cooperation Issawi Frej met with the Sudanese Justice Minister at a conference in Abu Dhabi. These encounters took place against a background of reports that the US administration had increased its pressure on Sudan to concretize the normalization agreement with Israel.

The Sudanese were reportedly disappointed at the slow pace of the economic aid they hoped to receive from the United States after signing the agreement with Israel. However, in late June, the International Monetary Fund and the International Development Union of the World Bank approved Sudan’s eligibility for debt relief as part of a plan to reduce the country’s international debt by 90 percent over three years, presumably facilitating the new arrangements for economic aid. To the extent Sudanese officials are able to link such economic relief to the normalization agreement with Israel, they would likely find greater incentive to promote it at home.

In any case, an attempted coup in Sudan in September, a further round of protests against the transitional government in mid-October, and the latest reports of a military takeover illustrate the fragility of the current government, which raises questions over the viability of normalization between Sudan and Israel.

Continuing to be part of the driving force of the #AbrahamAccords it was a pleasure meeting today with the Minister of Justice of #Sudan @nasabdulbari. We agreed on future cooperation between the two countries under the accords. 🇮🇱🇸🇩

1/3 pic.twitter.com/zcT9zZKzZE— Idan roll - עידן רול (@idanroll) October 13, 2021

Up Next: The Accords’ Potential in the Current Strategic Landscape

The Abraham Accords offer much potential, particularly (but not only) in the economic realm. Naturally, the agreements facilitate the development and promotion of economic activity between the Gulf states and Israel, which until now was conducted quietly or indirectly, and above all strengthen relations in the areas of R&D and technology, health, climate and environmental protection, water and waste, and advanced agriculture. However, there is a considerable gap between the number of memorandums of understanding and deals actually signed, including in security matters, and some of the deals currently reaching maturity began to take shape before the Accords were signed.

An Israeli foothold in the Gulf has the potential to provide an opening for deals with other Arab countries with which Israel has no relations, formal or otherwise, and an opening for expanded economic contacts in Asia. For example, one of the benefits of the Abraham Accords is a shortened air route to East Asia for tourism, business, and cargo flights. In a similar vein, the agreement with Morocco opens significant opportunities not only for economic investment and cooperation within the kingdom but also for economic engagement with countries of West and sub-Saharan Africa, two regions in which Morocco has deepened its presence considerably over the last twenty years. Likewise, Sudan is desperate for economic investment, and the agricultural sector especially could offer substantial opportunities for Israel investment. Indeed, the Arab partners in the Abraham Accords expect normalization with Israel to bring them economic rewards – an expectation that has increased with the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Israel, for its part, has an interest in seeing these expectations fulfilled and felt in the Arab street, to demonstrate the benefits of peace.

Apart from the need to strengthen relations that already exist (vertical normalization), Israel is interested in using agreements already signed to widen the circle of peace (horizontal normalization). If some states assess that drawing closer to Israel will also enhance their relations with the United States, improve their sometimes extremist image, and earn other economic and political dividends, they may well gradually soften their opposition to normalization.

One of the most important countries in this context is Saudi Arabia. The kingdom has internal and regional sensitivities, and there may be disagreements on the matter among the Saudi elite – the assessment is that King Salman has reservations about publicizing ties with Israel, while his son, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, is more pragmatic on the matter. However, there is a gradual and slow change in attitude to the Israel question and there are signs of compromise. The signing of an Israeli-Saudi peace treaty would presumably give the normalization process an important religious imprimatur and make it easier for other Muslim countries to ride the wave; hence the value of a possible future treaty with Riyadh, beyond the kingdom’s regional weight. It remains difficult to predict when and on what terms Riyadh would agree to join the Abraham Accords, but it appears that the Saudis are preparing the ground for an agreement, particularly with regard to public opinion, which is still largely opposed to normalization with Israel. The kingdom will want to examine two parameters: the continuation and expansion of existing normalization agreements (Riyadh has an interest in seeing other Arab and Muslim countries joining the process, which will help to provide legitimacy for its own move) and relations between Israel and the Palestinians. Other encouraging factors would include American consent to sell the kingdom advanced weapons, internal changes in Saudi Arabia, Israel’s improved standing in Saudi public opinion, and who will inherit the Saudi throne, in view of the apparent disagreements in the palace over normalization with Israel.

Saudi Arabia has already come a long way from its traditional position in order to support the Abraham Accords, and has taken measured steps towards normalization with Israel in what has amounted to a kind of “creeping normalization.” This policy of “support from outside” was reflected in the kingdom’s decision to grant Israeli airlines permission to fly in Saudi airspace, in the (relatively positive) coverage and commentary in the many media outlets owned by the kingdom, and in statements by senior figures, past and present. Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan even announced that normalization of relations between the countries would have "tremendous benefits" for the kingdom and the entire region, and that this was just a matter of time. However, he stressed the kingdom’s commitment to a resolution of the Palestinian issue based on the Arab Peace Initiative.

Regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the actions of the Gulf states to date suggest that given the right balance of incentives and pressure, some are likely to take steps that deviate from the Arab consensus. The same can be said for Morocco: while the kingdom has consistently supported a two-state solution enshrining Israel’s right to exist, the recent Israel-Hamas confrontation demonstrated that even a supportive country like Morocco may calculate it is necessary to cultivate ties with Israel’s adversaries in the service of its broader national interests. If Israel finds itself in disagreement with the Arab “normalization quartet” over its policy in the Palestinian arena, this could make it harder for countries such as Saudi Arabia to normalize relations, as they would prefer to continue sitting on the fence until more convenient conditions emerge.

An additional observation concerns the United States. The normalization agreements signed in 2020 required significant deliverables from Washington, and while other Arab states contemplating diplomatic openings with Israel are well aware that the current US administration is not keen to incentivize such openings using transactional tactics, they can be expected to continue viewing normalization with Israel as an opportunity to develop closer ties with Washington. But to this incentive should be added the Abraham Accords themselves. To the extent Israel and its newfound allies demonstrate that those agreements benefit the populations of the countries in question (and not merely the security establishments or the elite business communities therein), Arab regimes that are currently wavering may find additional reasons to take steps toward normalization – quite apart from currying favor with Washington.

Thus, insofar as the Abraham Accords have undermined the assertion that peace between Israel and Arab countries depends on a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, they reflect an improvement in Israel’s strategic standing in the Middle East. This breakthrough – while not inevitable and certainly not irreversible – was made possible by considerable US incentives. Paradoxically, however, a key factor fueling closer relations between Israel and these and other countries was the shared perception that the United States is retreating from the region. Uncertainty over the US presence and involvement in the region, particularly in view of the recent withdrawal from Afghanistan, could reduce the chances for further normalization agreements if Washington is busy with more urgent matters. On the other hand, the probability of further agreements in the foreseeable future could increase if other Arab countries see relations with Israel as a strategic advantage in the absence of a strong American security umbrella.

There is still considerable difference in how each agreement is implemented. At one end of the spectrum, the agreement between Israel and the Emirates remains the strongest of the four, while in contrast, the agreement with Sudan has not yet produced significant results in bilateral contexts. Between these two extremes lie Israel’s relations with Morocco and Bahrain, which have recently gained diplomatic momentum. In spite of the collective association of the four accords under the banner of the Abraham Accords, the past year has shown that the bilateral relationships will continue to be shaped above all by the particular interests and constraints of the individual states in question.

Finally, the developments surrounding the escalation between Israel and Hamas in May 2021 suggest that the normalization agreements will likely withstand future similar outbreaks of violence in Gaza and the West Bank. However, even the strongest agreements are not immune to the shockwaves of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Although Israel should act with diplomatic openness towards other Arab countries, irrespective of developments in the Israel-Palestine arena, Jerusalem must be prepared for the probability that such ties will be tested if the core issues between Israel and the Palestinians remain unresolved.

Policy Recommendations

Every country has its individual set of considerations and critics on the home front. Some states are reluctant to advertise their relations with Israel at the present time, particularly if it emerges that the existing agreements cannot influence Israeli policy in the Palestinian context. However, Israel can take a number of steps to strengthen the existing agreements and expand the circle of normalization:

In the broader context of economic ties, Israel can give priority to initiatives that focus on improving conditions for the younger generation in these countries. For the Arab regimes, this could have a stabilizing effect, and for Israel an improvement in its image among the next generation of leaders.

Wherever possible, Israel should incorporate the involvement of Egypt and Jordan into its emerging partnerships with the Gulf states, Morocco, and even Sudan. Such integration, particularly in the economic realm, would not only yield diplomatic dividends by allaying concerns in Cairo and Amman that Israel’s neighbors are excluded and left behind, but it would also strengthen the Jordanian and Egyptian economies and stave off the possibility of instability on Israel’s borders.

Regarding the Gulf states, Israel has an interest in initiating cooperation and responding positively to proposals from the Gulf, while avoiding over-enthusiasm and not pouncing on the Gulf economies. Credibility and respect for the laws of the countries in question, informed by observance of local cultural and business codes, will help Israeli entrepreneurs. Indeed, Israel would do well to remember that the Gulf market is also open to competitors that are hostile to Israel, which demands caution when marketing sensitive technologies.

Israel’s Arab citizens, endowed with advantages of language and culture, could find an opportunity in the Abraham Accords. The Israeli government should involve them in the developing relations, for example by way of inclusion in economic delegations to the Gulf and Morocco, and direct investments from those countries to industrial zones in Arab towns.

In the Palestinian arena, the normalization agreements present additional incentive to ensure that any military escalation, particularly with Hamas in Gaza, remains short-lived and targeted to avoid jeopardizing Israel’s burgeoning relations with the wider Arab world.

Israel should encourage elements in the Arab world that have formal or informal relations with it to show willingness for involvement in the reconstruction of the Gaza Strip.

Israel should work with the United States to leverage the Abraham Accords in order to improve its image in the international arena, and at the same time use its improved contacts with the “normalization quartet” to enhance contacts with other Muslim countries in Africa and Asia.