Publications

INSS Insight No. 1092, September 6, 2018

In the quest for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the idea of a Jordanian-Palestinian federation/confederation, which has been raised from time to time, has recently resurfaced. In a September 2, 2018 meeting between Palestinian Authority Chairman Abu Mazen and a group of Israelis, the Palestinian leader said that the idea was raised by the US team engaged in the effort to renew the negotiations between the parties and formulate a proposal for a settlement. Beyond the major question regarding the Palestinians’ political and legal status in the American proposal, a confederation model, particularly one involving Jordan, the Palestinians, and Israel, creates a possibility for “creative solutions” to issues related to economies, energy, and water. A trilateral framework of this nature may also facilitate solutions that include relinquishing elements of sovereignty for the sake of the confederation.

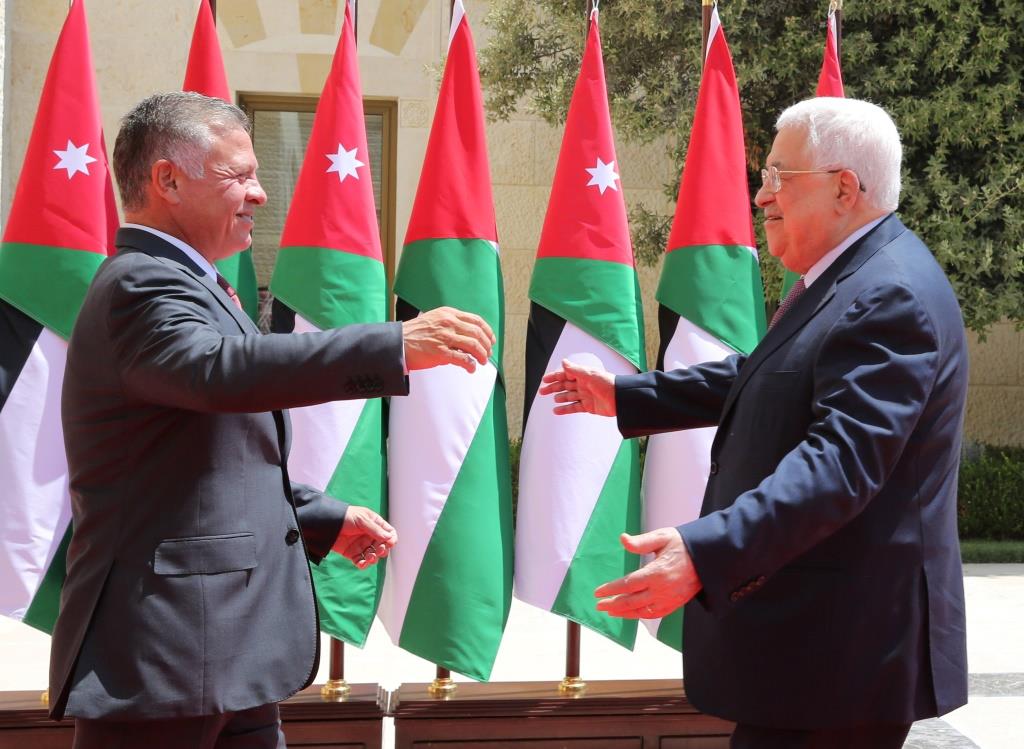

In the quest for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the idea of a Jordanian-Palestinian federation/confederation, which has been raised from time to time, has recently resurfaced. In a September 2, 2018 meeting between Palestinian Authority Chairman Abu Mazen and a group of Israelis, the Palestinian leader said that the idea was raised by the US team engaged in the effort to renew the negotiations between the parties and formulate a proposal for a settlement.

A federation is a regime with a number of sub-state units organized in one system where major powers pertaining to the economy, security, and foreign relations are held by a federal government. The United States is one example of a federal regime. A confederation, on the other hand, is a structure consisting of two or more states, each of which maintains its own independence and sovereignty, but is willing to entrust some elements of its sovereignty to the institutions of the confederation. Although no international entity currently exists that deems itself a confederation, many international organizations are based on this principle – that is, relinquishing certain elements of sovereignty in order to form one entity.

The idea of assigning a role and/or status to Jordan in the context of the Palestinian issue has been raised in the past by various elements in Israel that were not necessarily of the same ideology. The governments involved did not, for different reasons, pursue the issue beyond laconic rejections by Jordan, and expressions of “yes, but” on the part of the Palestinians. As to Israel, official elements have ignored the idea, or hinted that if the establishment of a Palestinian state is not a precondition, Israel would be willing to discuss it.

The Evolution of the Idea

From virtually the moment the 1967 Six Day War ended, different elements in Israel and Jordan began discussing the question of how to restore Jordanian control over the territory conquered by Israel - with the exception of Jerusalem, which already in the initial days following the war was approached differently than the West Bank. During the secret talks that King Hussein conducted with official Israeli envoys following the war, the interlocutors discussed possibilities for a gradual return of territory to Jordanian rule, beginning for example with the Jericho area. The events of Black September (1970), the Israeli government’s reluctance to take a decision regarding partial withdrawal from the territories in the Sinai Peninsula and the West Bank that were conquered in 1967, and subsequently the Yom Kippur War of 1973 brought an end to this stage of contacts between Jordan and Israel with no change in the situation. In 1977, the rise to power in Israel of a government that advocated strengthening Israel’s ideological, practical, and legal connection with the territories was manifested in different ways, including revival of the Biblical names of parts of the country, such as Judea and Samaria. This ostensibly marked the death of the idea that Jordan would play some future role in administering the territories.

The political bloc that advocated territorial compromise returned to power as a partner in Israel’s national unity government (1984-1988). This enabled Shimon Peres, in his capacity as Foreign Minister during the second half of this government’s tenure, to conduct secret negotiations with King Hussein regarding the “Jordanian option,” meaning the return of Jordanian rule to the territory that was occupied in 1967. Peres’s inability to secure the consent of Prime Minister Shamir and his government to an agreement that was reached in 1987 during the talks with King Hussein resulted in Jordan’s formal disengagement from all claims to what had been Jordanian territory, announced in a speech by the King on July 31, 1988. This was the second death, as it were, of the idea of Jordan’s return to the West Bank. The first intifada, which erupted in 1987, undoubtedly contributed to the King’s decision to separate the two banks of the Jordan River.

The Oslo Accords - which established the Palestinian Authority and in which Israel agreed to conduct negotiations with the Palestinians on a final status agreement regarding the territories that were occupied in 1967, including, according to the language of the agreements, Jerusalem – should have reinforced the end to the “Jordanian option.” Surprisingly, however, this option was reborn when both opponents and advocates of Israel’s withdrawal from the territories breathed new life into it. The liberals among those who advocated maintaining Israeli control of Judea and Samaria, with the exception of specific parts of the territories, regarded Jordan, already home to most of the population that is of Palestinian origin, as an alternative to an independent Palestinian state in Judea and Samaria. Based on the understanding that the population of these territories would not emigrate on their own volition, and on a desire to avoid creating a population lacking full political rights living under Israeli rule, these elements proposed that the Palestinian population in Judea and Samaria be able to vote and run for office in Jordanian elections.

The failure to reach a full solution regarding the political future of Judea and Samaria in the negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians prompted those who advocated Israel’s disengagement from these areas to seek alternatives, one of which was Jordan’s resumption of an active role in administering the territories that Israel would evacuate. However, this hope that Jordan could provide an alternative to a Palestinian state or constitute the state that would meet the West Bank Palestinians’ demands for political expression is a sheer illusion.

King Hussein’s 1988 speech not only expressed disappointment with Israel’s refusal to adopt the agreement he had reached with Peres (and representatives of the US administration), but also reflected the belated understanding that if he wanted to preserve the Hashemite rule in Jordan, he would need to disconnect himself from all direct responsibility for Judea, Samaria, and even Jerusalem. Article 9(2) of the Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty of 1994 states that “Israel respects the present special role of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in Muslim Holy shrines in Jerusalem,” but does not provide a detailed definition of Amman’s role or clarification regarding the sites involved, beyond the Temple Mount/Haram a Sharif. It also says nothing further about Jordan’s role or status in any territory that was occupied by Israel in 1967.

The understanding that some Israelis, and perhaps some Palestinians as well, view Jordan as “the alternative homeland” (in Arabic, al-Watan al-Badil), and fear an increase in the Palestinian segment of the Palestinian-Jordanian population and, as a result, potential demands to provide this majority with political-constitutional expression, is of major concern to Jordan’s Hashemite monarchs. The kingdom’s general conduct regarding a host of challenges, particularly those pertaining to the Palestinian issue, is understandable only in the context of this Jordanian reality. The laconic response of Jordan’s Minister of Public Diplomacy regarding a report that Abu Mazen told Israelis who met with him recently that members of the American team on the negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians had raised the idea of a Palestinian-Jordanian confederation left no room for doubt regarding Jordan’s position: that the matter is closed and not up for discussion, and that the Palestinians have the a right to their own country.

The position expressed by Abu Mazen was more complex and perhaps also more constructive. He did not reject the idea out of hand, and said he might be interested provided Israel were part of the confederation. His spokesperson, Nabil Abu Rudeineh, clarified that the idea has been on the agenda of the Palestinian leadership since 1984 and would be a framework that complements the two-state solution. Arafat himself also did not rule out the idea of a Jordanian-Palestinian confederation, but insisted that it could be actualized a minute after the establishment of a Palestinian state, and not before. Israel’s official public response to the idea of a two or three-pronged confederation has still not been articulated. This can be explained not only by Israel’s desire to avoid friction with Jordan, but also by its desire to avoid all commitments and obligations to the establishment of a Palestinian state, which the Palestinians regard and will continue to regard as a precondition for their agreement to a confederation.

If Abu Mazen’s report regarding the American proposal and the report by the Israelis who met with him recently are accurate, a number of questions arise. The first is whether the American proposal makes clear reference to two independent entities. Is Abu Mazen’s failure to reject the idea an indication that he finds the other sections of the plan – regarding Jerusalem, for example – acceptable? The tense relations between Abu Mazen and President Trump and the US administration raise the question why he Abu Mazen chose to reveal such a significant detail of the American plan specifically now. It is not clear whether the Palestinians considered the possibility that the confederation idea was “planted” among the members of the American team by Israel, out of a desire to bypass the question of sovereignty. Hamas’s response and that of the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood show that they view the American idea as damaging the two-state solution.

Beyond the major question regarding the Palestinians’ political and legal status in the American proposal, the tripartite model creates a possibility for “creative solutions” to issues related to economies, energy, and water. A trilateral confederate framework may facilitate solutions that include relinquishing elements of sovereignty for the sake of the confederation. In any event, trilateral solutions in these realms are preferable.

Although Jordan’s possible resumption of a practical governing role in the West Bank seems at best illusory, the possibility of future Jordanian involvement in solving certain elements of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict cannot be ruled out, particularly perhaps the political and legal casing that would enable both Israel and the Palestinians to accept solutions that circumvent national honor.