Publications

INSS Insight No. 1037, March 21, 2018

What is known as “the Begin Doctrine” instructs that countries that are hostile to Israel and that call for its destruction must not be allowed to develop a nuclear military capability that could be used against Israel. Israel’s attacks against the nuclear reactors under construction in Iraq and in Syria achieved total destruction of the reactors, and without casualties. Moreover, history has shown that in light of the developments that followed the respective attacks, the nuclear programs of Iraq and Syria were postponed for significantly longer periods than might have ensued through “technical delays.” However, these two cases do not necessarily point to a doctrine that will be eternally viable. Israel’s enemies have learned the lessons of the attacks on the reactors in Iraq and in Syria, and they have built more difficult challenges in face of potential attack. Thus, the State of Israel’s current and future leaders will not escape the need to thoroughly analyze strategic targets and risks in the future context of enemy plans to develop and be armed with nuclear weapons.

The decision to attack a nuclear reactor in enemy territory is one of the most difficult decisions that an Israeli leader may face. Prime Minister Menahem Begin drafted the unofficial doctrine that is named for him, “the Begin Doctrine,” seeking to prevent countries hostile to Israel calling for its destruction from developing a nuclear military capability.

There are critical arguments against a decision to attack a nuclear reactor in an enemy country:

a. Operational risks: The reactors are high value targets that are well protected, and thus an attack incurs the risk of casualties and possible mission failure, which might compound strategic embarrassment with strategic and political costs. Incidentally, Israel’s attack on the reactor in Iraq in 1981 was launched shortly after the botched American attempt in 1980 to rescue the hostages trapped in the United States embassy in Tehran, a failure that resulted in human and material costs and loss of prestige.

b. Political risks: The international community opposes preemptive strikes and deems them acts of aggression rather than self-defense. Consequently, international sanctions and punitive measures are possible responses to an attack, and these may result in significant strategic costs.

c. Risk of deterioration into war: The enemy’s response might be wide scale and painful – from missile fire and attacks on high value targets in Israel, to all-out war, particularly if there is a common border.

d. Positive alternatives: over time, additional, less radical solutions than attack might emerge. Perhaps the regime hostile to Israel will change, or the world powers will be challenged to put a stop to a nuclear program in a rogue state, as was the case with the Libyan nuclear program. In this context, in 2007, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert indeed asked US President George W. Bush to attack the reactor in Syria, but this request was denied.

e. Attacking a nuclear reactor is only possible before it is hot, i.e., it can only be destroyed long before operational capability has been developed. And herein lies the dilemma: at an early stage, attack feasibility is high while legitimacy is low, but by the time legitimacy arrives, attack is not an option. Postponing the decision to attack gradually rules out any ability to destroy the reactor.

f. In technical and engineering terms, destroying a reactor can only postpone “the inevitable” by a few years, assuming a regime is determined to acquire nuclear weapons. Sometimes the attack itself might accelerate the effort to acquire a nuclear weapon.

Therefore, before the Israeli government decided to attack nuclear reactors, in 1981 in Iraq and in 2007 in Syria, thorough deliberations were held, and disagreements arose at both the political and military echelons about the pros and cons of carrying out the attack.

However, with the perspective of hindsight, those who argued that the risks outweighed the severe danger of nuclear weapons in the hands of dictators who are declared enemies of Israel and who call for its destruction were clearly correct. Saddam Hussein and Bashar al-Assad, who had no qualms about using chemical weapons against their own people, could have constituted extremely dangerous enemies had they been armed with a nuclear weapon. The Islamic State, the unbridled terrorist organization that took control over major areas of Syria and Iraq (including over the actual Syrian reactor site in Deir ez-Zor) could definitely have gained access to fissile material and perhaps even a nuclear weapon had the reactor not been destroyed by the Israeli attack in 2007 – a development that would have exposed the entire world to unprecedented risks.

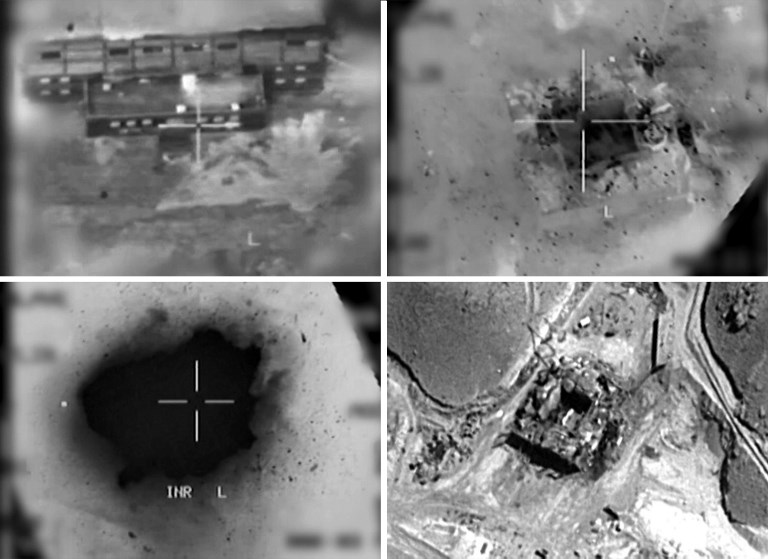

Despite the operational complexities, Israel’s attacks against the nuclear reactors under construction in Iraq and in Syria achieved total destruction of the reactors, and without casualties. The strike against the reactor in Iraq was a far more complicated mission than the attack in Syria, because it was carried out amidst advanced Iraqi air defenses system on high alert, and was conducted by the Israel Air Force with no air-to-air refueling capability or precision munitions. In contrast, the main challenge in Syria in 2007 did not derive from operational aspects, but rather, from the desire to prevent a war following the attack. In 1981, Iraq was incapable of waging a war against Israel, as there was no common border between the two countries. Iraq at that time had no long range missiles capable of reaching Israel, was engaged in an all-out war against Iran. However, in 2007, Syria was poised for war against Israel from the common border, and it had missile and chemical arsenals. In addition, Damascus drew confidence then from what was perceived as Hezbollah victory against Israel during the Second Lebanon War in July-August 2006.

Ultimately, the Iraqi and Syrian responses were minimal and did not lead to war. The Iraqi Scud missiles fired on Israel in 1991 – a decade after the attack – were perceived as Iraq’s retaliation for the attack, but against the backdrop of the Gulf War, the missiles would likely have been launched in any event, in an attempt to undermine the American-Arab coalition against Iraq. In the Syrian case, where the outbreak of war after an attack was a more realistic possibility, that scenario was avoided thanks to the wise Israeli strategy of not claiming responsibility. This silence granted Bashar al-Assad “room for denial,” and saved him the need to respond militarily to the attack, or even denounce it. Interestingly, in 1981, although there was a similar decision not to take responsibility, Prime Minister Begin opted, apparently due to the upcoming elections, to take responsibility for the Israeli attack.

Overall, the international response to the Israeli attack on the Iraqi reactor was fairly moderate: while it included condemnations and sanctions, they were of short duration. In 2007, following the attack in Syria, the response was supportive, because a defiant, recalcitrant country such as North Korea supplied the reactor, because the project was concealed from the International Atomic Energy Agency, because Israel had informed its key allies beforehand and countries important to it after the operation, and because Israel did not take responsibility for the attack.

Most importantly: history has shown that in light of the developments that followed the respective attacks, the nuclear programs of Iraq and Syria were postponed for significantly longer periods than might have predicted by any theoretical or scientific parameters. Despite the motivations of Iraq and Syria to rebuild their nuclear programs, the reconstruction was postponed, inter alia, because circumstances diverted attention and resources from the nuclear programs and completely changed the regimes’ balance of considerations. The 2003 war in Iraq and the civil war in Syria guarantee that the nuclear programs of these two states will not be resumed, at least for decades.

However, these two cases do not necessarily point to a doctrine that will be eternally viable. Israel’s enemies have learned the lessons of the attacks on the reactors in Iraq and in Syria, and they have built more difficult challenges in face of potential attack. In operational and political terms, the Iranian nuclear program (like the defunct Libyan program) is based on centrifugal enrichment of uranium, which can be dispersed, concealed, and protected more effectively than more vulnerable nuclear reactors. The defense of nuclear programs, particularly air defense, will continue to improve, and consequently exact a heavy price in the event of an attack. Thus, the State of Israel’s current and future leaders will not escape the need to thoroughly analyze strategic goals, options, and risks in the future context of enemy plans to develop and be armed with nuclear weapons.