Strategic Assessment

Our argument in this article is that the challenge of integrating the ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) community into Israeli society impacts national security from a perspective that has not been addressed until now – namely, its detrimental effect on Israel’s ability to maintain a modern, productive economy capable of generating the output necessary to support significant defense expenditures. These expenditures are a prerequisite for sustaining a modern military and, therefore, for the survival of the state. To substantiate this claim, an analysis is presented focusing on the following aspects: Damage to GDP—a gap in state revenue generation through taxes; high transfer payments from the state to the ultra-Orthodox sector, including allowances and balancing grants; the non-participation of the ultra-Orthodox in the security burden, which intensifies the load on productive groups and increases the economic cost of reserve and regular military service. The article concludes with proposed solutions to the problem.

Keywords: Ultra-Orthodox sector, defense expenditure, GDP, transfer payments, defense economy

Introduction

Much has been written over the years, especially recently, about the non-participation of the ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) community in bearing the burden of national security. This issue has broad social and moral implications, rooted in the exemption from military service granted at the establishment of the state to a limited number of yeshiva students, which was expanded without numerical limitation in 1977. Currently, during the Swords of Iron war, this exemption applies to approximately 12,000 yeshiva students annually (a total of about 63,000 draft-eligible yeshiva students are exempt at this point in time).

The societal problem has been amplified during the war, given the number of fallen and wounded—both physically and mentally—the exhaustion of regular combat soldiers, and the enormous burden placed on reservists. This article does not deal with the issue of drafting the ultra-Orthodox, which we hope will be resolved through legislative changes and their conscription like other Jews in the state. Instead, it provides a different perspective on the connection between the ultra-Orthodox sector and national security. This article is based on two fundamental premises:

- For Israel to survive in the Middle East, it needs a modern military equipped with advanced weaponry on a large scale and staffed by high-quality, well-trained personnel capable of operating it.

- To sustain such a military, Israel requires a modern, productive economy capable of generating sufficient output to support significant defense expenditures with minimal strain on the economy.

The article argues that the ultra-Orthodox sector undermines Israel’s economy in three direct economic ways and one indirect social way. Given the second premise, this economic harm translates into harm to national security. The three direct economic ways are:

- Damage to GDP—A gap in state revenue generation through taxes.

- High transfer payments from the state to the ultra-Orthodox sector, including allowances and balancing grants.

- Non-participation in the security burden, which increases the load on productive groups and the economic cost of reserve and regular military service.

All these constitute economic harms that we will attempt to quantify later. Additionally, there is another indirect harm of great importance, though difficult to quantify: the fact that the ultra-Orthodox sector’s non-participation in the economic burden contributes to the hardships of life in Israel in various aspects and pushes productive citizens to leave the country.

It should be noted that there is a partial similarity between the economic harm caused by the ultra-Orthodox sector and that caused by the Arab sector. However, there are significant differences: The ultra-Orthodox sector seeks to continue its current patterns, while the Arab sector is moving in the opposite direction—making an increasing contribution to the economy, motivated by a desire to improve living standards, reduce family size (and thus lower child allowances), and currently, by law, is not a significant potential pool for military service.

The Impact on Israel’s Economy[1]: Damage to Growth and Reduction of GDP

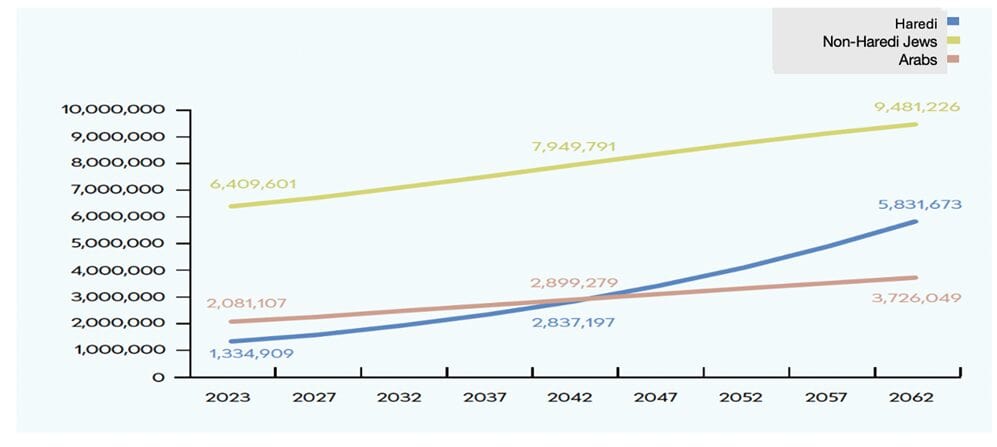

According to estimates by the Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2023, the ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) population in Israel, based on self-definition, numbered approximately 1,335,000 people, constituting 13.6% of the total population. By 2030, it is expected to reach 16% of the total population. The annual natural growth rate of the ultra-Orthodox population has been 4.2% since 2009.

Chart 1: Population Forecast by Population Group, 2023–2062 (in absolute numbers)

Source: The Annual Report on Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel 2023, Chart A/5

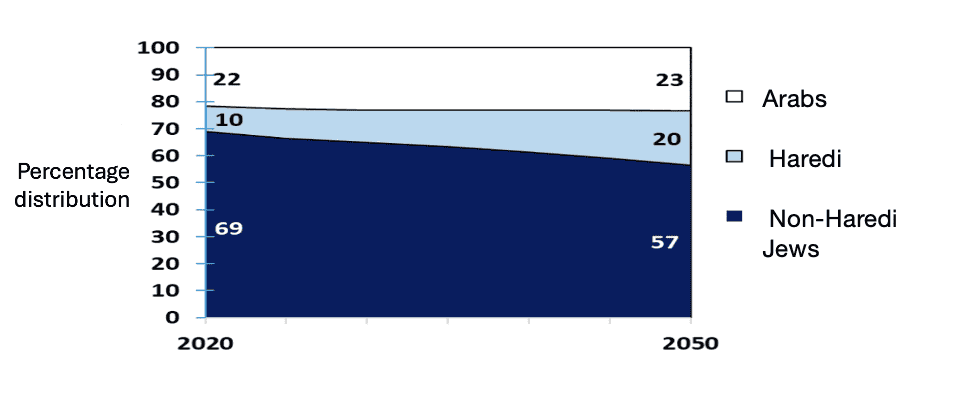

The proportion of ultra-Orthodox individuals in Israel’s working-age population (20–65) is expected to double by 2050.

Chart 2: Composition of the Population by Major Ethno-Religious Groups, Ages 20–64, Israel 2020–2050

Source: The Future of Israeli and Jewish Demography, Chart 4

This figure has significant implications for GDP potential due to the low participation of the ultra-Orthodox in the workforce and the low level of education within this community, which affects wages.

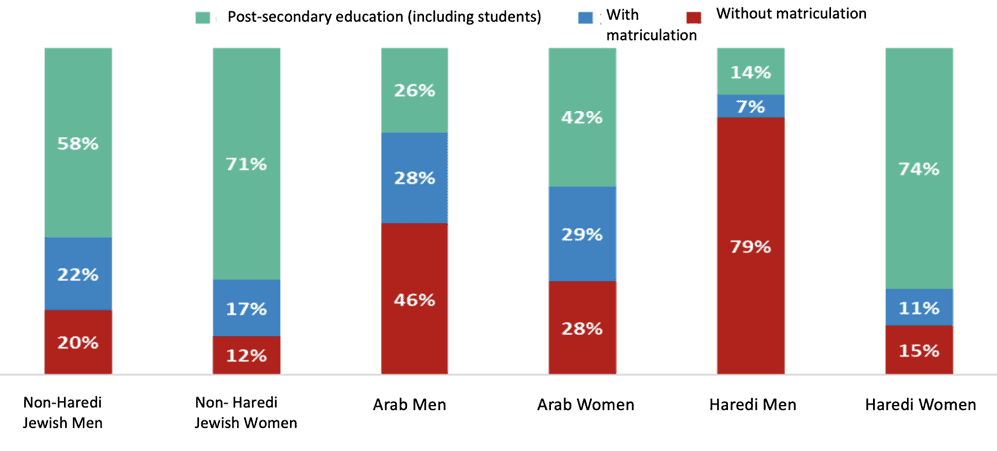

Ultra-Orthodox Education: In the 2022–2023 school year, approximately 390,000 students studied in ultra-Orthodox primary and secondary education. They comprised 26% of all students in Hebrew education and 20% of all students in Israel. However, the percentage of ultra-Orthodox students eligible for a matriculation certificate among 12th-grade students is very low, standing at only 16%, compared to an eligibility rate of 86% in state and state-religious education. The percentage of those eligible for a matriculation certificate meeting university admission requirements (at least four units in English) is even lower, at just 10% in ultra-Orthodox-supervised education.

In the 2022–2023 academic year, approximately 16,700 ultra-Orthodox students studied in academic institutions, constituting 5% of all students studying in Israel that year. Chart 3 below demonstrates the distribution of education levels by population groups in Israel as of 2022, for those aged 25–34.

Chart 3: Distribution of Education Levels by Population Group, 2022, Ages 25–34

Source: Education Levels of Young People and Their Implications, Chart 1

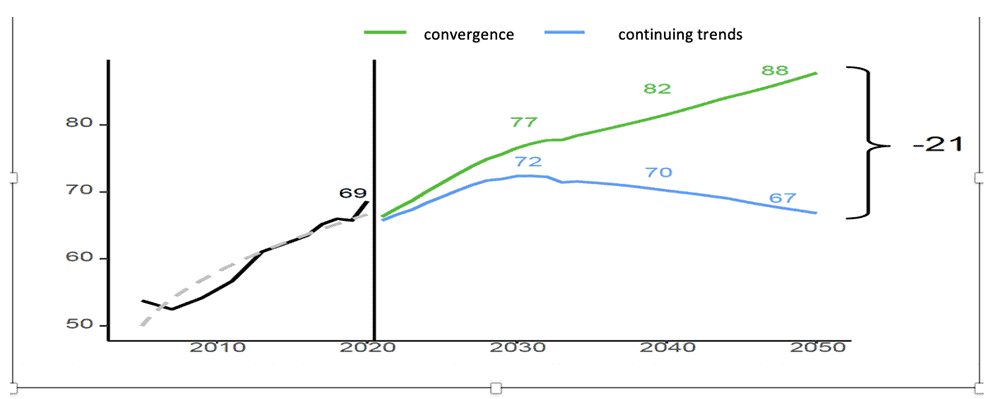

The projected trend for Israel’s overall human capital, assuming current population and education trends continue, is a decline in average education levels and a corresponding loss of employment and GDP potential. Chart 4 shows the development of matriculation eligibility rates according to current trends versus a scenario of the convergence of the Haredi trends with the rest of the population.

Chart 4: Matriculation Eligibility Rate by Different Scenarios

Source: Israel 2050: Demographic Projections, Slide 4

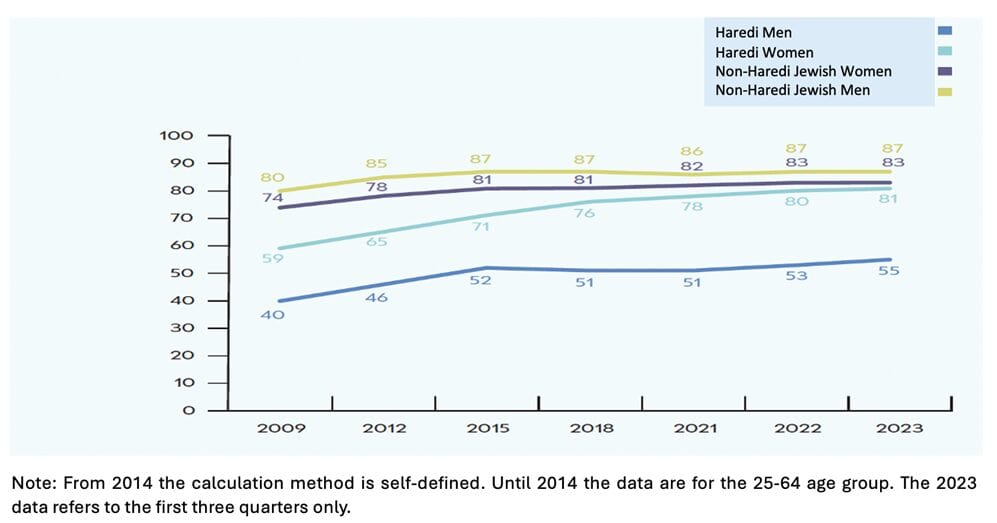

Employment: The employment rate of ultra-Orthodox men (53%) in 2022 was significantly lower than that of non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish men (87%). The gap between employed ultra-Orthodox women and employed non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish women during the same year was much smaller (79.5% compared to 83%).

Chart 5: Employment Rates Among Those Aged 25–66, by Population Group and Gender, 2009–2023 (in Percentages)

Source: The Annual Report on Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel 2023, Chart D/2

The Expected Impact on GDP Due to Continuing Trends in Employment, Education, and Wages in the Ultra-Orthodox Population

According to the 2019 long-term growth model developed by Eyal Argov and Shai Tsur, the factors influencing long-term growth are: the population of prime working ages (25–65), worker characteristics (primarily participation in employment and education), capital (physical and intangible assets), and total productivity (technology and other factors). Among these, the relevant factor for analyzing the impact of trends in the ultra-Orthodox population on GDP is worker characteristics—namely, participation in the labor force, education, and wages.

The trends outlined above indicate a decline in worker characteristics. The increasing proportion of ultra-Orthodox individuals within the working-age population—given the low employment rate of ultra-Orthodox men and Arab women, low education levels, and low wages, which directly affect productivity—leads to an estimated reduction in growth of up to 6% by 2065, according to Argov and Tsur’s model.

The chief economist analyzed the effects of each sector separately (Arabs and ultra-Orthodox), based on gender, employment, and wages. His conclusions differentiate between the medium and long term. In the medium term, closing the gaps in the Arab sector contributes more to growth, whereas, in the long term, the situation is reversed. Closing the gaps in the ultra-Orthodox sector in the long term would add 0.6% growth annually, equivalent to a 22% increase in the annual growth rate (from an average of 2.7%–3.3% per year). A recent study by the Israel Democracy Institute, focused on the ultra-Orthodox population, estimated a cumulative GDP loss of approximately 10% by 2050, equivalent to about 160 billion NIS in 2023 terms.

The main barriers to the integration of ultra-Orthodox men into the labor market include: A significant lack of basic skills, such as knowledge of English and mathematics, and digital literacy, which hinders academic studies and work in technological fields; dedication to Torah study until age 26 as a condition for receiving an exemption from military service; a negative incentive to join the workforce due to the combination of direct and indirect state support for yeshiva students, late entry into the labor market, and the absence of adequate training, leading to reliance on occasional, unreported jobs; cultural and social gaps that hinder integration into high-paying industries.

Furthermore, a study by Noam Zussman and Avraham Zupnik examined the impact of a one-time reduction in the military exemption age to 22 in 2014 on employment, education, and income. The study looked at different age groups and showed that early entry into the labor market had an overall positive impact on the likelihood of being employed, gaining education, and increasing household income (with a slight decrease in women’s income, but less than the increase in men’s income). The chief economist also addressed the additional impact on ultra-Orthodox employment. His research suggests that improving employment incentives by 1,000 NIS per month would lead to a 4.7 percentage-point increase in the employment rate.

Transfer Payments

Numerous studies focus on the extent of state support for the ultra-Orthodox way of life.[2] These studies measure direct subsidies aimed at the ultra-Orthodox sector (for yeshiva students and married men, known as avreichim), which are budgeted by the government (in the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Welfare, Ministry of Religious Affairs, etc.), as well as indirect subsidies aimed at those from a lower socioeconomic status. Since the proportion of ultra-Orthodox families in this socioeconomic group is higher than in the general population, they receive indirect support that exceeds their relative share of the population. The main types of support include the avreich allowance (depending on marital status), daycare subsidies, child allowances (depending on the number of children and financial status), assistance for needy avreichim with municipal taxes and rent, income support, and more.

In an attempt to examine the full range of support, incentives, and benefits, we can rely on the latest comprehensive study by Ariel Karlinsky and his colleagues.[3] According to the study’s findings, an ultra-Orthodox family receives an average net total support, after deducting all the taxes it pays, of 6,115 NIS per month in 2018 terms, excluding public goods and infrastructure. This translates to about 73,500 NIS per year per family, amounting to 14.5 billion NIS annually (approximately 200,000 households) on excess support to ultra-Orthodox families.

Increasing the Burden on Military Service

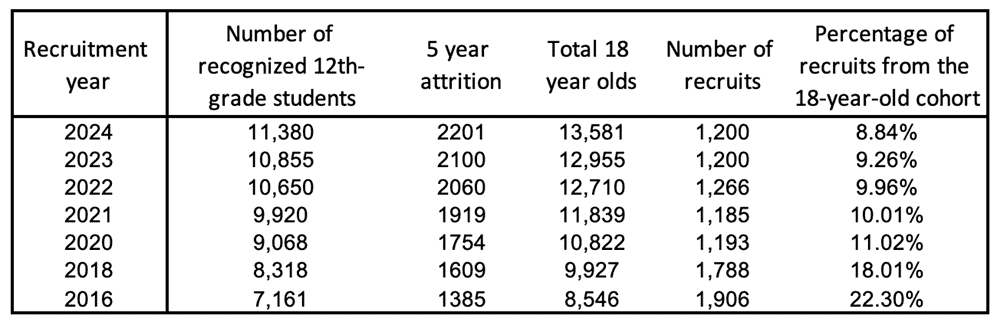

According to IDF reports from 2019, including projections for 2024, ultra-Orthodox enlistment in the IDF, as defined by the Security Service Law, is fairly stable at approximately 1,200 recruits per year. This number is also reflected in various publications by the Israeli Democracy Institute and the Knesset. However, a broader definition indicates the enlistment of about 1,800 ultra-Orthodox soldiers per year.[4]

It is difficult to calculate the enlistment rate among the ultra-Orthodox public for various reasons, including: the differing definitions between the Security Service Law and self-definition, as outlined in the publications of the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS); and because the annual enlistment data is calculated based on the recruitment year (July to June of the following year). For an approximation, one can use the number of 12th-grade students in the ultra-Orthodox sector (by school year). To this number, the dropout rate in recent years, estimated at 3.6% annually, should be added.[5] The data used in the calculation is a cumulative dropout over five years.

The calculation of the enlistment rate shows a decline of about half a percent each year in recent years, with a steeper decline compared to the years before 2019. The recruits are aged 18-28, so the calculation is not precise, but it serves as an indication of the decline in enlistment among this population.

Table 1: Development of recruitment rates in relation to the number of 12th-grade graduates, with an additional 5-year dropout rate.

If the Haredi recruitment rate could be brought in line with that of the rest of the population, to achieve an overall recruitment rate of 50% of the entire population, this could be enough to prevent the planned extension of mandatory military service by four months, or allow for its return to previous levels, again depending on the scope of recruitment, recruitment age, service period, and service occupation. For example, gradually raising the recruitment rate of the ultra-orthodox to 50% (in line with the rest of the population) for a two-year service period (similar to the Hesder Yeshivot for national religious recruits) at an age when most are still unmarried, with the goal of establishing battalions that can perform routine security operational duties along the borders, could shorten the service requirement for all recruits by four months within four years and also save significant reserve duty days. The expected savings to the economy in the first five years of implementation, due to shortening service and reducing the reserve duty burden, amounts to about 10 billion NIS, excluding the change in transfer payments[6], and about 4 billion NIS each subsequent year.

The Economic Damage in the Long-Term View.

The combined economic damage in the coming decade (2025-2035) is expected to be relatively low, as a significant portion of the population in the Haredi sector has not yet reached working age. However, in the following decade (2035-2045), the potential damage will reach large proportions. In total calculations for this decade, 60 billion NIS will be lost from GDP, 140 billion NIS from transfer payments, and 40 billion NIS from regular service and reserve costs—totaling approximately 240 billion NIS over the decade. This means a loss of about one and a quarter percent of GDP, which is significant, especially considering that the defense budget before the war was less than 5% of GDP, or roughly a third of the defense budget (more than the volume of American aid). It should be noted that much of the loss is already “lost” and cannot be fixed, since if in the preceding decade Haredi education did not include core studies, these students will not be able to integrate productively into the economy.

In the introduction, three direct economic factors impacting national security were mentioned, and one indirect factor. The indirect danger from the worsening situation is that, due to the inequality in the burden across all sectors, productive citizens who serve in the IDF may leave the country. Such a situation would further diminish Israel’s economic base and make its survival even more difficult.

A Look to the Future

What can be done to prevent or reduce the economic damage caused by the ultra-Orthodox sector to the security of the state? The following proposals are in the fields of education and knowledge. They are focused on the economic aspect, but could also contribute to addressing the growing need for equality in the burden of national service.

One group of responses is “positive” and entirely dependent on the implementation of core studies in the ultra-Orthodox sector, such as rewarding ultra-Orthodox parents who send their children to such educational institutions. The basis for change in the education sector may be the cancellation of the various streams of education in Israel and the creation of a unified education stream with basic and modern education for all, which will be determined by the Ministry of Education according to an analysis of the future needs of the economy, and will include additions tailored to different lifestyles (Jewish, Arab, religious, ultra-Orthodox, traditional, secular, atheist).

Options based on the education reforms:

- Creating high-paying work frameworks in the ultra-Orthodox sector while maintaining cultural differentiation between the employees within them—who will be purely ultra-Orthodox and will pursue limited hours of Torah study—and the workers in the general public.

- Temporarily subsidizing ultra-Orthodox workers entering the productive labor market through “retraining” incentives, so that this is more profitable than their work in non-productive professions or low-wage jobs.

- Continuing to allow ultra-Orthodox individuals to learn a civilian profession while serving in the military.

A second group of responses concerns economic sanctions, as well as other areas:

- Sanctions of the type currently in place—reducing economic rights that have been granted until now, such as daycare subsidies.

- New sanctions in various areas of life, for example, raising fees for services in the health system according to the non-productive work of parents of working age.

- Creating a connection between paying taxes to the state and receiving services from the state, distinguishing between those who need services due to limitations not under the individual’s control (such as disability, illness, old age, inability to be employed due to a temporary crisis in a particular sector, like tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic) and those who are “voluntary poor,” who do not work for personal convenience and are supported by the state.

- A more extreme proposal is social and governmental separation, in the spirit of Eugene Kendal and Ron Tzur’s proposal to create a new federal regime model, which would allow groups with conflicting values in Israeli society to have a formal right to autonomy concerning their values and way of life, and to stop feeling coerced or needing to defend themselves.

Summary

In order to survive as a country and as individuals, the State of Israel requires a modern army, and for that, a modern economy. A continuous increase in the absolute size of the Haredi sector and its relative size within the population of Israel, along with its continued non-participation in productive economic activity, rising transfer payments, continued economic burden from non-conscription into the military, and shortage of manpower in regular and reserve service (as well as income concealment in the black market)—all of these directly harm the state’s ability to maintain such an army. The scenario presented in the article indicates a gap of one and a quarter percent in GDP due to these factors. Cities in Israel that have undergone a process of Haredization have dropped in socio-economic rankings. A prominent example is Jerusalem, which dropped from a ranking (with 10 as the highest and 1 as the lowest) of 5 in 1995 to a ranking of 2 in 2019, while Arab neighborhoods strengthened due to a decline in birth rates. Safed, which dropped in 2010 from a ranking of 4 to 3, further dropped to a ranking of 2 in 2017. These cities have turned from productive cities into needy cities. In the ongoing process we are facing, the entire state could become a “needy state.” The danger is that long before that, Israel could be defeated on the battlefield due to the gaps in its economic capacity to maintain the required modern army for its survival.

The Israeli public debate about social-moral inequality in the security burden, arising from the refusal of the Haredi population to enlist in the military, should therefore also address the economic harm to security caused by the Haredi sector, and it should be done sooner rather than later.

-----------

[1] The economic analysis in this section is primarily based on research conducted by Sasson Haddad at the Jewish People Policy Institute, as part of a special project led by Prof. Yedidia Stern: “The Recruitment of Ultra-Orthodox: Military, Economic, and Legal Aspects – A Framework for Integrating the Ultra-Orthodox into the IDF,” 2024, unpublished. Hereinafter: Stern, 2024.

[2] Additional examples: On taxes and wonders: Distribution of state income and expenditure among households in Israel, the importance of financial incentives for the employment rate of ultra-Orthodox men.

[3] A draft is due to be published in the Quarterly for Economics.

[4] The number 1,200 refers to the definition of an ultra-Orthodox person in the Military Service Law (at least two years of study in a “yeshiva ktana”, which is an ultra-Orthodox yeshiva for high school ages, and only institutions recognized by the Ministry of Defense). The IDF has a different method of categorization, which includes other ultra-Orthodox institutions, according to which it recruits 1,800 ultra-Orthodox individuals per year.

[5] In the document linked, there are two issues: The issue of not counting dropouts and the issue of which date the year is counted from. However, according to our understanding, the overlap issue is minor because the recruitment data refers to graduates of a specific academic year.

[6] The assessment based on the economic analysis in Stern, 2024.