Publications

INSS Insight No. 1903, November 10, 2024

After a year of war, it is time to reassess Israel’s fundamental strategic alternatives and the contrasting views that have figured prominently in the professional disputes, media opinions, and public discourse regarding the war, its trajectory, and continuation since its outbreak.

For Israel, the war against Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran’s regional proxies and, recently, Iran itself began with the October 7 disaster—a military nadir. The war has continued throughout the year with periods of seemingly little strategic progress, a severe crisis in Israel’s standing in international public opinion, acute tensions coupled with unprecedented cooperation with the United States, a drastic downturn in Israel’s economy, extreme fluctuations in national morale, and a return to the stark polarization within Israeli society. While the trajectory of the campaign has shifted in recent weeks and months, the ongoing tragedy of the Israelis kidnapped and held by Hamas continues to cast a long shadow over the war and the decisions surrounding it.

From the perspective of one year, it is time to reassess the fundamental strategic alternatives facing Israel during the war and the different views that have been at the center of professional disputes, media opinions, and public discourse. To be clear, this article does not attempt to provide a weekly or monthly chronological narrative of the events, nor does it examine all the decisions, some crucial, made during the war. It certainly does not purport to assess the web of considerations, decisions, and responsibilities in the years preceding the war and the surprise and failures of October 7 itself. Instead, this article focuses on a retrospective reassessment of major alternatives and policy and strategic courses of action at the core of the debate about the war’s direction and continuation since its outset over the past year.

Whether or not to Enter the Gaza Strip

The October 7 disaster raised the critical question of how Israel should respond. Prominent figures in defense and politics expressed doubt about the IDF’s capacity to conduct a large-scale ground invasion of the Gaza Strip to eliminate Hamas’s massive military infrastructure and pressure it to release the hostages, as well as to deliver a crushing blow to the prestige that Hamas had gained among the Palestinian and Arab public through its surprise attack.

Some commentators warned against a ground invasion, instead advocating a response limited to airstrikes and small-scale ground incursions. This was also the American view. It should be noted that Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar likely expected this kind of response, believing that Israeli society would be unable to withstand the cost of an all-out war in the dense urban landscape of the Gaza Strip and would also be fearful about the fate of the hostages. Sinwar therefore expected Israel to restrict its response primarily to air attacks and limited operations, which he believed Hamas could survive.

However, the Israeli public’s extraordinary unity and determination after October 7 were consistent with the strategic understanding of Israel’s leadership, after some initial hesitation and hectic consultations. The decision to conduct a massive incursion into the Gaza Strip stemmed from the belief that the war initiated by Hamas posed an existential challenge to Israel—not because Hamas or Hezbollah were capable of conquering Israel, but because failing to respond decisively to the October 7 disaster would embolden jihadist groups throughout the Middle East and, in turn, would turn Iran’s “ring of fire” into a boundless political and strategic reality, making life in Israel impossible. Contrary to the claims of some commentators, Israel’s deterrence has always been, and still is, a fundamental condition for its existence in the Middle East and, in the long term, for the region’s acceptance of Israel’s existence.

Ground operations began in the northern Gaza Strip, with the capture of Gaza City and its suburbs. A massive force of several divisions was concentrated in a small area for a number of reasons: Israel focused on the area closest to its center (the area in the Gaza Strip with the shortest rocket range to Israel), which was also regarded as Hamas’s main stronghold and the location of its leadership; and aimed to test the operational capability of Israeli ground forces, in combination with the air force, which had not experienced serious fighting for some two decades.

The capture of the northern Gaza Strip proved to be an extraordinary success, and the IDF losses were less than feared. Following this success, Hamas agreed to a deal in which nearly half of the hostages (some of them foreign citizens) were freed in exchange for a limited ceasefire that lasted for one week. Hamas hoped that the ceasefire would lead to the end of the war and the IDF’s withdrawal from the Gaza Strip.

Hamas was disappointed, however, when Israel chose to continue the war. Nonetheless, Israel’s growing international isolation following the scenes of death and destruction in the Gaza Strip, the open wound of the remaining hostages, periods of seemingly little military progress in the field, and a rising number of casualties increasingly undermined the public consensus over the war. The exhilaration resulting from the successful early stages gave way to deep depression, and the dispute about the continuation of the war and its objectives emerged in full force.

Following the attack in the northern Gaza Strip and the splitting of Gaza into two, the Israeli offensive effort concentrated on the Khan Younis theater. It was believed that most of Hamas’s command was located there, led by the Sinwar brothers. While the high-intensity effort in northern Gaza took only a month, the campaign in Khan Younis and its environs, led by the 98th Paratroopers Division, continued for four months. Hamas’s fighting formations were demolished, and most of its field command was destroyed. The IDF’s expertise in underground warfare—the primary operational challenge—continued to develop. However, the prolonged campaign, the almost daily losses incurred, and the failure to free the hostages and kill Sinwar led to a growing sense of frustration within the IDF and a sense of public disillusionment.

Rafah and the Philadelphi Corridor or a Ceasefire?

The decline in morale and the collapse of public consensus, as well as strategic disagreements, reached a peak during the prolonged campaign in Khan Younis. An American veto, along with Egyptian opposition, halted progress toward eliminating Hamas’s last major organized force in Rafah and severing the main smuggling routes to the Gaza Strip above and below ground—the Philadelphi Corridor and the Rafah Border Crossing. In retrospect, this action should have been taken at the start of the war, simultaneously with the conquest of the northern Gaza Strip. Added to this was the exhaustion of the Israeli regular and reserve forces and, above all, the painful question of the hostages.

This was the point at which the political and strategic debate intensified at full force, accompanied by a deep divide within the Israeli public. Against what appeared to be the continuation of a futile war in Gaza, fraught with heavy costs both internationally and economically, the possibility of a hostage deal and a temporary or final ceasefire was raised under strong American pressure. The question of the deal and ceasefire was shrouded in professional disagreements and public ambiguity. Most strategic experts believed that the war could be renewed, even if only partly, after a temporary lull and a deal for the release of the hostages, whose number and life expectancy in captivity were clearly dwindling. Some held that it was no longer possible to gain any more achievements in Gaza by war and that everything possible had already been achieved. A few held that the Israeli campaign had failed and that it was time for Israel to cut its losses.

In contrast, some—including the present author—believed that the key question was not what more could be achieved in Gaza but rather the fate of what had already been achieved. They held that great strides had been made in dismantling Hamas’s military infrastructure: Many of its combat formations had been eliminated; a large portion of its fighters and commanders had been killed or wounded; its central command, production workshops, and weapons stockpiles had been severely damaged; and a considerable number of its strategic tunnels had been located and demolished.

At the same time, it was argued that the prevailing discourse was largely illusory and that Hamas, emboldened by the international pressure on Israel, would not consent to any agreement that did not include a complete Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip and a total end to the war with international guarantees. Such a deal, it was argued, would allow Hamas to quickly regain control of the territory and rebuild its military power—perhaps not to the extent seen on October 7—but enough to make a renewed Israeli incursion into the Gaza Strip—even if it were possible vis-à-vis the international community—into a full-scale operation of reoccupation, with all its costs in terms of IDF casualties, which would be unacceptable to the Israeli public.

It was also argued that Hamas would be in no hurry to release the hostages, its main strategic asset. Instead, it would drag out the negotiations for months and years, extracting every possible advantage from them, inflicting maximum pain and humiliation, and breaking down Israel’s morale. Eventually, Hamas would insist on an exchange of “all for all,” including thousands of prisoners, among them those who had committed the October 7 massacre. Hamas’s ability to withstand Israel, regain control of the Gaza Strip, and free thousands of cheering Palestinian prisoners in an endless procession of buses would symbolize the victory of the “resistance,” swaying Palestinian and Arab public opinion in Hamas’s favor. Assuming that they managed to hold onto power, the moderate regimes in the Arab countries would struggle to contain the surge of jihadist enthusiasm and the intoxication of victory that would sweep over their peoples.

It seems that none of these factors were clear to the majority of the Israeli public, who understandably longed for a hostage deal. Some of the public, particularly those who regularly demonstrated for a hostage deal at the Kaplan intersection in Tel Aviv, expressed the belief that releasing the hostages was a supreme moral imperative that should be pursued at any cost. Some speakers rejected any discussion of the potential price in lives of such a deal, even if it were ten times the estimated number of hostages believed to have survived in captivity. These advocates ignored the heavy costs in lives of the Jibril and Gilad Shalit deals and their consequences—namely, the entrenchment of kidnapping Israelis as a major goal for terrorist organizations and the inflation of their price. A minority among the protestors held that even the possibility of losing many more lives in the future justified a hostage deal now as a supreme moral imperative. It is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the strength of this protest bolstered Sinwar’s belief that the liberal and affluent Israeli society was incapable of resisting pressure and extortion.

The political calculations of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the absolute priority he assigned to the survival of his coalition contributed to the renewed polarization in Israeli society regarding the war. The extent of the prime minister’s use of security agencies and negotiators as pawns in his political campaign was unprecedented among prime ministers across the political spectrum. This could not have failed to infuriate them and exacerbate the sentiment among the government’s numerous opponents that it was illegitimate. The Kaplan demonstrations (for a hostage deal) and Balfour protests (against the prime minister and the government) underwent an accelerated merger process that hindered objective assessments of the available options regarding the hostages.

Against this backdrop, the question of entering Rafah and seizing the Philadelphi Corridor took on a divisive political character. The proposed operation became the subject of a mudslinging campaign filled with apocalyptic warnings about its anticipated results. Still, many viewed it was essential for the complete destruction of Hamas as a quasi-state military organization with massive military infrastructure. Ultimately, after months of delays, the IDF seized control of the Philadelphi Corridor despite American restrictions and amid a continued public controversy, and systematically dismantled Hamas’s presence in Rafah’s neighborhoods until it was crushed as an organized fighting force.

The Turnaround

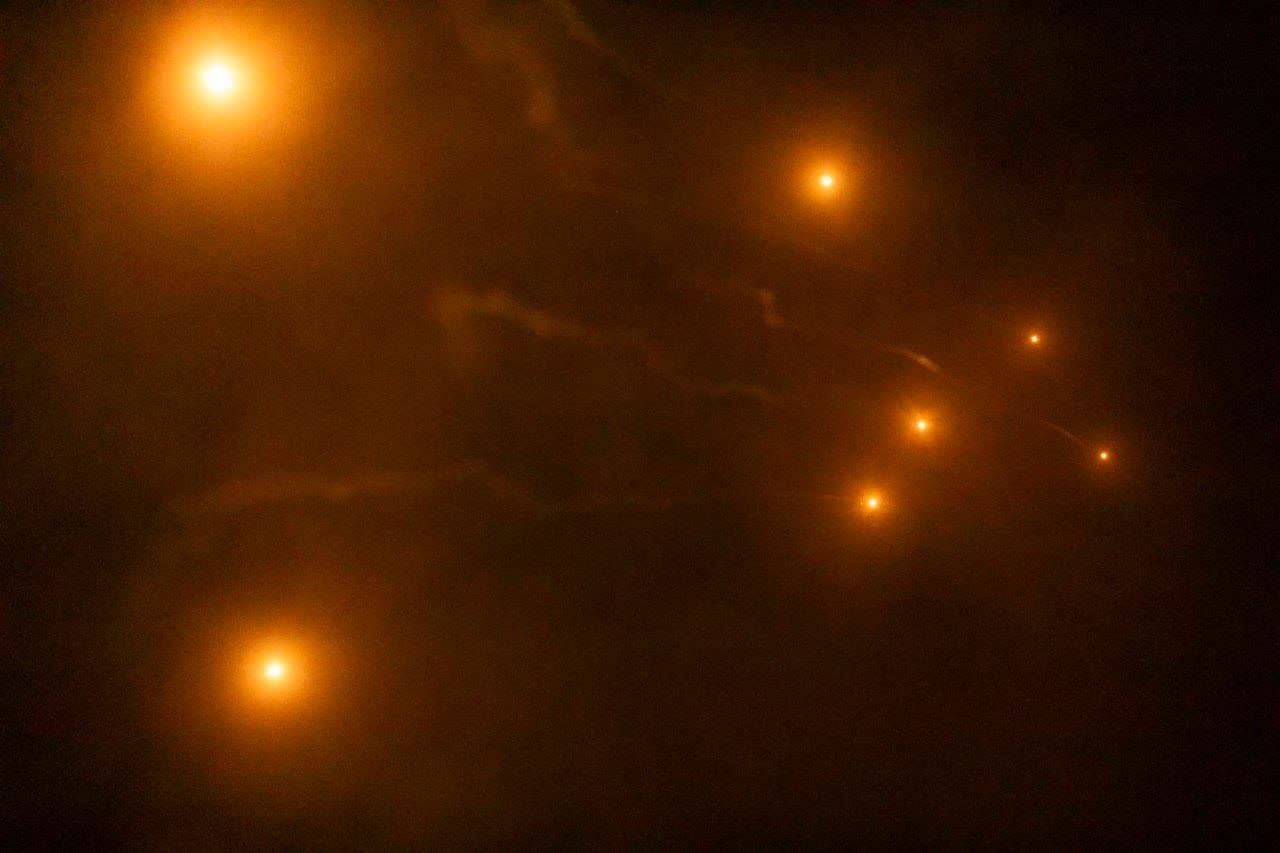

The low point in public morale and expert assessments occurred in the first half of 2024. Since that time, a number of electrifying Israeli operations signaled the beginning of a turnaround in sentiment: the elimination of senior commanders in the Iranian Quds Force in Damascus; the killing of Mohammed Deif, head of Hamas’s military wing and one of its most prominent symbols; a devastating air attack on Hodeida Port—the Houthis’ main economic lifeline in Yemen—and the facilities it contained; and the assassination of Hamas Political Bureau chairman Ismail Haniyeh in the heart of Tehran. A number of commentators criticized the attacks against the Quds Force commanders and Haniyeh as mindless provocations that culminated in the first-ever direct intensive Iranian missile attack against Israel in April—a sharp deviation from Iran’s traditional policy. This attack, which was intercepted by Israel with American assistance and tacit cooperation from a regional coalition, caused only negligible damage.

The turnaround became a huge tidal wave when the IDF shifted its effort to Israel’s northern border. At the beginning of the war, a proposed preemptive attack against Hezbollah before the beginning of operations against Hamas was rejected. In retrospect, given the later success against Hezbollah, it is no longer clear whether the proposal was as illogical as it appeared at the time. For its part, Hezbollah decided to limit its assistance to Hamas to tying down large IDF forces to the Lebanese border and launching a ceaseless stream of rockets against what it called military targets in northern Israel. Given the concern of the residents and the defense establishment about a ground invasion from Lebanon along the lines of the October 7 attack from Gaza, a controversial decision was made to evacuate some 60,000 Israelis from the border, and a limited pattern of a war of attrition took shape along the entire border for a year.

Several considerations led to the prolonged postponement in addressing this insufferable situation in northern Israel. As long as the intensive effort in the Gaza Strip, which took much longer than expected, was still ongoing, there was an understandable reluctance to open a second front on the Lebanese border. Furthermore, the Americans—who controlled the flow of armaments and other essential elements of their support for Israel—exerted all their influence to prevent an Israeli attack in Lebanon, fearing that Iranian intervention could trigger a regional war and could entangle the United States against its will.

As an alternative, the American administration expressed its belief that the diplomatic effort it was spearheading would lead to a ceasefire in the north. This was linked to a hostages deal and ceasefire in Gaza—and to a Hezbollah withdrawal to the Litani River as part of an overall diplomatic agreement between Israel and Lebanon involving renewed implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1701, as demanded by Israel.

As noted above, many people in Israel would have gladly accepted a potential agreement to end the war in Gaza, hoped it would occur, and believed it was feasible. However, the notion that a ceasefire, which Hezbollah would likely have accepted, would be followed by its withdrawal north of the Litani River was patently hopeless. After many months of intensive negotiations, it became clear that reaching such an arrangement was impossible, and the Americans eventually had to acknowledge this fact, albeit in a qualified and halfhearted way. They were left with little justification for preventing an Israeli operation, without which the evacuees could not return to their homes.

The conclusion of the high-intensity phase of the war in the Gaza Strip, even without a formal ceasefire and an end to the war, allowed for a redeployment of IDF ground forces to the north, while the concentration of the air force had, for some time, been only minimally contingent upon the continued fighting with Hamas. Nevertheless, there were valid reasons for Israel’s hesitation to expand the war against Hezbollah, beyond its concerns about a regional war with direct Iranian involvement. Israel had been burned many times in Lebanon and believed that Hezbollah could not be destroyed in the same manner as Hamas’s military collapse had been achieved in the limited area of the Gaza Strip, which was isolated from the rest of the world. Furthermore, even if Israel’s capacity to intercept missiles was high, concerns about Hezbollah’s ability to inflict considerable damage on population centers and critical infrastructure were grounded in reality.

Some argued that a war against Hezbollah at this time exceeded Israel’s military, international, and economic capabilities and was hindered by the erosion of the IDF’s manpower and equipment. They suggested accepting an end to the war now on almost any terms, buying time to better prepare the IDF and the country for a future conflict in later years. Not only did this provide no feasible means of returning the evacuees to their homes in the north under the shadow of Hezbollah; it was also unclear whether Hezbollah and Iran would not take advantage of the ensuing years to build up their forces even more effectively than Israel and the IDF could.

In light of the above and given the reasonable assumption that a violent clash in the north, whether short or prolonged, would eventually lead to some political agreement, the question arose as to why an agreement could not be reached before initiating a war with unpredictable results. The diminishing hope for such an agreement and the evacuees’ acute distress ultimately led to a decision for a higher-intensity operation against Hezbollah, the outcomes of which provided a clear retrospective answer to the question whether a war can profoundly change the subsequent situation.

Guided by precise intelligence, the use of the air force against Hezbollah yielded the crushing results hoped for before the war, and decisively restored confidence in the IDF’s integrated air-intelligence capability which had been severely undermined on October 7. It transpired that in a theater for which the IDF had been planning for years, its success was extraordinarily impressive. The systematic destruction of Hezbollah’s launching systems, the devastating impact on its command and control structure from the simultaneous explosion of pagers and walkie-talkies, and the series of targeted killings that eliminated Hezbollah’s entire leadership, including Nasrallah, stunned Hezbollah, Iran, and the Arab public. Compounding the effect was the enormous wave of refugees that flooded Lebanon, most of them Shiites from the combat areas.

A Strategic and Policy Assessment

It should be emphasized that everything generally accepted about the nature of war remains valid. War is indeed a realm of uncertainty, and the recent wave of successes should not lead to euphoria, just as there was no reason to sink into depression during the difficult points of the year. The path to ending the war, at least in its intensive phase, remains unclear and fraught with risks. Nevertheless, looking back on the events, the fundamental decisions made following the October 7 disaster appear correct in principle, despite delays and periods of seemingly slow progress—some of which were likely necessary, while others probably resulted from less justifiable hesitations and postponements by the leadership. Indeed, all this occurred amid the unbearable political noise that accompanied the decisions and undermined their credibility.

Criticisms of the war’s management and the proposed alternatives should be examined carefully, one by one, and evaluated within the context of the general assessment of the situation following the October 7 disaster.

None of the alternatives proposed at the outset and during Israel’s ground operations in the Gaza Strip to destroy Hamas’s extensive infrastructure and prevent its reemergence were practical. Israel faced an existential challenge, as defined at the beginning of the article, and had to take all necessary measures to reverse the situation. Against those who claimed that the war highlighted Israel’s weaknesses, the crescendo of recent weeks and months decisively rectified this impression—certainly regarding the military aspect and its regional implications.

The damage to Israel in the international public opinion, especially in the West, is severe and profound. The scenes of destruction and death in the Gaza Strip horrified large segments of the public. The aggressive demonstrations by Muslims and radical leftists flooded both physical spaces and social media, forcing even sympathetic governments to reconsider their stance on Israel and its dire situation. This is the heavy price that Israel had no choice but to pay.

There was no way to eliminate Hamas’s massive deployment, deeply entrenched in the urban landscape from which, in addition, thousands of missiles were fired at the civilian population in Israel, without causing enormous destruction. Anyone who claims that such destruction is unacceptable should provide other practical and convincing methods that would break Hamas’s power in the Gaza Strip. Otherwise, they are effectively arguing that Hamas should have immunity from attack. Many people in the West have evaded this question, and some seem to be effectively in favor of granting Hamas such immunity under the circumstances.

In this context, we recall previous instances when Israel fought for its survival and encountered a cold shoulder and even hostility from Western countries and public opinion. This was the case during the Yom Kippur War, when Europe closed its airports to the American airlift to Israel, and during the gloomy decade that followed. It was also the case in the year after the Second Intifada in 2000, when public opinion and many governments favored the “wretched of the earth” in Palestine, even after the Palestinians had been offered a state with Jerusalem as its capital but still chose to wage war. Only 9/11 changed perspectives and helped rescue Israel from its plight. None of this prevented, or could have prevented, Israel from doing what was essential for its security.

Having said all this, it should be emphasized that the current makeup of the Israeli government, with extreme right-wing parties and their veto power over decisions, has significantly undermined Israel’s legitimacy. Irresponsible statements about total war and starving the population in the Gaza Strip, along with extremist visions—some of them messianic—about destroying the Gaza Strip once and for all, expelling its residents, annexing parts of it, and renewing Jewish communities there, have created a grave negative impression. This has been compounded by cases of Jewish terrorism and calls for a Gog and Magog war of redemption in the West Bank. It has been difficult to convincingly explain that this is not the official policy of Israel and its government.

Indeed, the deliberate avoidance by Netanyahu and his government of any discussion about the future of the Gaza Strip at the conclusion of the high-intensity phase of the war has largely stemmed from the prime minister’s political constraints. Not only has the international suspicion and criticism of Israel increased, but it may have directly harmed the war’s success.

A substantial part of the discourse and proposals concerning a “diplomatic leg” for the war has been largely detached from reality. Any attempt to establish an alternative leadership in the Gaza Strip based on local groups and major clans has been doomed to fail, given Hamas’s murderous grip on the territory. International forces—Arab or otherwise—will not fight Hamas. Their fate would likely resemble that of the American marines in Beirut in 1983 or the UN forces in South Lebanon. Instead, their presence would likely inhibit Israeli military action against Hamas, as it is difficult to envision Israel conducting military operations in disregard for the presence of such forces.

An Israeli military government in the Gaza Strip responsible for distributing supplies and providing services, while denying them to Hamas, will lead to daily Israeli casualties among the forces and agencies deployed in the area, not to mention the heavy operational, logistical, and financial burdens it will incur.

By contrast, the proposed entry of the Palestinian Authority (PA) into the Gaza Strip, suggested at the campaign’s outset, is arguably the least harmful option. The PA will not fight Hamas, as its leaders well understand they lack the forces and legitimacy to do so. However, its presence would partly alleviate Israel’s civilian and legal responsibilities in Gaza. Moreover, the PA would be unable to prevent Israel from continuing its operations against Hamas “above the PA’s head,” as Israel currently does in the West Bank. The more Hamas weakens in the war, the PA option may become more viable. Hopefully, it is not too late to revive this idea, despite the low likelihood of the current government adopting it. This should have been Israel’s official stance from the beginning of the war, with appropriate safeguards, not to mention its public relations and visibility value vis-à-vis friends and supporters in the West.

Critics argue that Hamas is resuming political control and military activity in nearly all areas where the IDF has withdrawn. From the outset, however, Israel anticipated that after intense fighting to dismantle Hamas’s organized power and military infrastructure, Israel would resort to a “mowing the grass” strategy, similar to the approach used in the West Bank for years. As expected, Hamas has shifted to guerrilla warfare in Gaza, and the campaign against it in this form is likely to continue for years. The elimination of Sinwar can be expected to have a similar stunning operational and consciousness effect as the killing of Nasrallah.

Despite the IDF’s considerable successes against Hezbollah, the path to a ceasefire in the north that keeps Hezbollah away from the border and allows the evacuated Israelis to return home is far from clear. It is difficult to envision Hezbollah willingly accepting the humiliation of conceding to Israel’s terms after suffering substantial losses. Although Israel has embarked on ground operations in South Lebanon to destroy Hezbollah’s infrastructure, remaining there would only make Israel vulnerable to Hezbollah’s guerrilla warfare tactics, as in the past. It is very doubtful that the diplomatic efforts now taking place to check Hezbollah’s political power in Lebanon, strengthen the Lebanese army and UNIFIL, and harden the stipulations of UN Security Council Resolution 1701 will bear significant results. However, since the return of the Shiite population to its towns and villages also depends on the stability in the north and Israel’s approval, this could enable a de facto ceasefire along the border. Once Israel withdraws from the territory, it should apply maximum force both from the air and through ground raids to prevent any return by Hezbollah to southern Lebanon.

Obviously, much depends on Iran, which is seeing its “ring of fire” project and the jewel in its crown, Hezbollah, being severely beaten. Iran is now facing the same dilemma that Israel previously encountered: whether to risk a regional war that might involve the United States or to exercise restraint and change direction to some extent. Against the growing dominance of the Revolutionary Guards in Iranian politics and in shaping policy in recent years, the new reform government in Iran favors improving its connection with the West to obtain the removal of economic sanctions imposed on it.

On October 1, the Iranian leadership chose to fire 180 ballistic missiles at Israel, most of which were intercepted, causing relatively little damage. Iran emphasized that it had no desire to escalate further. Israel responded by a measured, and still highly effective, strike, mostly directed at Iran’s air defense and ballistic missile systems, demonstrating the superiority of its air force and Iran’s vulnerability. Iran is reported to ponder it response, signaling that one will come. This would seem to defy rationality, for if indeed Iran chooses to attack, its highly vulnerable oil industry might be targeted this time. An attack on the Iranian nuclear facilities could provoke Tehran to hasten the development of a bomb. And in any case, only the United States has the ability to effectively stop Iran’s development of nuclear weapons—the main threat—through a new deal, even more biting sanctions, or military force.

It is uncertain whether and how the dramatic developments regarding Hezbollah and Iran could help secure the release of hostages by Hamas. Israel should make a supreme effort and be willing to pay a high price, while also seeking creative ways to solve the painful problem of the hostages without making commitments that would allow Hamas to restore its power. At the nadir of the war, some argued that no victory was possible without the return of the hostages, even at the cost of halting the war and withdrawing completely from the Gaza Strip. Against this, it was argued that there is a significant difference between non-victory and a crushing defeat for Israel involving Hamas’s survival and resumption of its governing role and military prowess. Meanwhile, Israel’s situation has greatly improved and Hamas’s organized power has been dismantled; and yet allowing it to regain control remains unacceptable.

What Did We Learn in Relation to IDF Force Building?

Following the difficult events at the beginning of the war, the claim that IDF ground forces had been excessively reduced due to cuts made over the past two decades gained traction. It was suggested that the ground forces had been neglected in favor of the air force, intelligence, and special units in the belief that large-scale wars had ended. This consensus was largely attributed to prewar criticism by General (ret.) Itzhak Brik. The present author noted that the IDF now had more field divisions than it had possessed during the Six-Day War and even the Yom Kippur War in 1973, when it faced a coalition of regular Arab armies totaling nearly 20 divisions and thousands of tanks. In the current war, the IDF has mobilized more than 300,000 reservists compared to 30,000 Hamas combatants and 40,000–50,000 Hezbollah combatants. Recall that in the Second Gulf War, the United States conquered all of Iraq with only 4–5 divisions. The IDF’s problem in the current war has not been a shortage of forces but technological gaps in critical spheres. Despite the heroism shown by its troops, the primary challenge lies in coping with the tunnels underground and with drones above ground. The IDF needs high-tech breakthroughs in these critical areas. At the same time, a fundamental change is required in at least one low-tech sector—a re-creation of home defense forces to counter October 7-type surprise attacks, which call for relatively lightly armed and inexpensive forces.

It appears that the IDF is moving in precisely these directions. Conscript service has been extended to its former three years, and efforts are being made to fill the ranks, with an emphasis on reinforcing combat engineering units, whose key role has been highlighted in the war. However, there is no plan to add combat field divisions. Instead, the establishment of the 96th Division, a new home defense unit, was announced. This unit, composed of soldiers previously released from reserve duty, will be responsible for defending the home front communities, critical installations, and communication arteries. Local community alert squads are also being strengthened and placed on a higher state of readiness. In addition to augmenting its units and equipment for combating tunnels, the IDF is focused on strengthening its deployment of light intelligence and attack drones and equipping itself with various means of interception, including laser systems, against enemy drones, UAVs, and missiles. Equipping every armored fighting vehicle (AFV) with the revolutionary Trophy and Iron Fist active defense systems, now reportedly upgraded for more comprehensive protection against aerial threats, is crucial. A leap in the IDF’s effectiveness is achievable by investing in these means and by enhancing the connectivity and automation of the ground forces’ weapon systems, rather than by increasing the number of its divisions.

Brik’s assertion that investments in the air force were misdirected and came at the expense of the ground forces is fundamentally invalid, as evidenced by the war, which has refuted most of his warnings and doomsday predictions during its course (thought not concerning IDF readiness and alertness before the war). Contrary to his criticism, the air force too was reduced to half its size compared to the 1990s, mirroring the cut in the number of ground field divisions. The air force played a critical role in supporting the ground forces in the Gaza Strip, demonstrating exemplary cooperation between the two. Enemy missile fire did not disrupt the functioning of its bases. The massive strikes delivered by the air force, including the elimination of Hezbollah’s leaders, stunned even those familiar with its capabilities. While ground forces, with air support, were essential for addressing the challenges posed by the Gaza Strip tunnels and for operations against Hezbollah, recent developments in the Lebanese theater have shown that the combat doctrine primarily relying on air-intelligence cooperation is not as unrealistic as previously thought. Furthermore, the air force is still the most powerful and flexible strategic reserve at the disposal of the IDF’s high command that can be easily shifted from one front to another. It serves as Israel’s strategic arm against distant threats, particularly as a deterrent and the primary offensive force against Iran.

Israel’s defense budget was gradually reduced from between a quarter and a third of GDP following the Yom Kippur War—the lost decade of the Israeli economy—to 4.5% of GDP in recent years (not including American aid). This is significantly higher than in any other developed country, including even the United States. After covering the exceptional costs of the war and reconstruction, the budget should return to this level. Budget restraint should not be abandoned due to the October 7 trauma.

Interim Conclusion

At the beginning of the Yom Kippur War, Israel suffered a severe military blow, and the war’s aftermath led to one of the gloomiest decades in Israel’s history. Nevertheless, Israel regained its composure during the war, avoided a defeat, and turned the tables on its enemies, paving the way for the diplomatic achievements that followed, culminating with the peace with Egypt. One may hope for a similar outcome this time.

Israel was heavily hit on October 7 and afterward, suffering significant losses in life and severe damage to its foreign relations, economy, and morale, some of which may be long term. It is important to remember that the war is not over. However, the recent turnaround is restoring, and perhaps even bolstering, the perception of Israeli deterrence power, which had been critically weakened. The “spiderweb doctrine” and dreams of Israel’s destruction, through the coordinated popular mobilization efforts of all the fanatical elements of the Iranian-sponsored “ring of fire,” have largely been buried under the ruins of the Gaza Strip and Lebanon. The moderate Arab regimes are pleased with the downfall of Hezbollah and Iran’s difficulties and are encouraged by these developments. Having regained its image of superior military capability, Israel is once again becoming a critical ally of the moderate Arab regimes against the Iranian threat. This development has the potential to advance the process of normalization and cooperation with these regimes, which had been partially stalled and called into question during the war, at least in its overt aspects. In the long term, although the roots of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict are deeper and more complex than those with the second and third circles of Arab countries, there may be potential for a more positive dynamic—albeit limited and realistically calibrated—in the Israeli–Palestinian sphere.

The author’s views on the subjects discussed were expressed during the war in the following publications of the Institute for National Security Studies:

“The Aims of the War in Gaza—and the Strategy for Achieving Them,” INSS Special Publication, February 26, 2024, https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/special-publication-260224.pdf.

“Expanding Israel’s Ground Forces or Prioritizing Technology?,” INSS Special Publication, March 24, 2024, https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/special-publication-240324-1.pdf.

“Caution, The New Concept—From Overconfidence and Complacency to Distress,” INSS Insight, no. 1871, July 1, 2024, https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/No.-1871.pdf.