Strategic Assessment

Since its inception, the Zionist Movement has been accompanied by a sense of “demographic inferiority.” It was a struggle between two national movements for the same piece of land—a kind of “zero-sum game.” Naturally, the demographically weaker side—the Zionists—tried to close the gap as much as possible through both immigration and encouraging higher fertility among the Jews in the Yishuv. However, while the sense of demographic inferiority among the Zionist movement prior to the establishment of the State of Israel and even after it is understandable, it was supposed to diminish after the Oslo Accords, and even more so after the withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, with the main purpose of both to achieve a “demographic separation” from the Palestinians. The peace agreements with Egypt and Jordan; the collapse of the “eastern front” after the elimination of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003; and the outbreak of the civil war in Syria were all expected to mitigate the Israeli sense of demographic inferiority even further. In effect, however, this was not the case, and the feeling of “demographic inferiority” changed into a “demographic appetite,” which perpetuated the concept of “growing as much as possible.” This paper aims to examine why every Israeli government, whether “right-wing” or “left-wing,” has sought to maximize the number of Jews in Israel; the implications of the various governmental demographic policies for the standard of living of Israel’s citizens; and finally, the external demographic threats to which Israel is exposed. The main conclusion of this paper is that even without the annexation of all or even part of the West Bank, Israel is experiencing steady rapid population growth, leading to increased crowding and accordingly a decline in the quality of life for its citizens.

Key words: demographic threat, natalist policy, the Law of Return, annexation, population density, cost of living, refugees, environmental quality

Introduction: What Is the Meaning of Demographic Threat?

The academic literature distinguishes between four types of demographic threat: The first and most common threat is the religious or ethnic majority/minority ratio, wherein the majority feels threatened by a minority demanding full or partial independence. Striking examples of such a threat are the Catalans and the Basques in Spain and the Kurds in Turkey and Iraq, who have been demanding autonomy or even full independence for many years, sometimes accompanied by violence against the regime (Laitin 1995).

The second type of demographic threat involves the fear of the country being inundated with migrants of different religions or ethnic backgrounds, thereby altering the cultural, religious, and ethnic character of the host country. The fear of being overwhelmed by non-white and non-Christian migrants has fueled the European right, particularly since the al-Qaeda attack on the United States (September 11, 2001), and has further intensified with the influx of Muslim Arabs into Europe since the onset of the Arab Spring (December 2010). Another striking example of this type of threat is the determined opposition of Arabs to Jewish immigration to Palestine during the British Mandate. A more recent example of the perceived threat of a change to a country’s religious-cultural character due to mass immigration can be heard in the words of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in July 2022: “We [Hungarians] are not a mixed race and we do not want to become a mixed race” (Walker and Garamvolgyi 2022).

The fear of losing cultural, religious, and ethnic identity, coupled with the escalating violence perpetrated by fundamentalist Islamic organizations in the Middle East and Europe, has led to a significant decrease in the pace of Muslim migration to Europe. Even German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who in September 2015 declared that “our economy is healthy, there is no limit on the number of refugees we can take in” (Calcalist 2015) and opened the gates of Germany to Arab Spring refugees, particularly Syrians, changed her policy a short time later. After the success of the right-wing party Alternative for Germany in the September 2017 elections, Merkel was obliged to change her immigration policy, and Germany began to restrict entrance from the Middle East (Shavit 2022; Shubert and Schmidt 2019). In order to limit the scale of migration from the Middle East and Afghanistan, since 2016 the European Union (EU) has paid Turkey billions of euros to prevent migrants from moving from its territory to the EU (Uni 2020).

The third type of demographic threat is an internal struggle that may be religious or ethnic, or sometimes both, for dominance in a country. A clear example of this type of demographic threat is that all internal struggles throughout the Arab region since the onset of the Arab Spring, without a single exception, are based on religious and/or ethnic grounds. This is the situation in Yemen, Syria and Iraq, as well as in Lebanon almost since its independence. In each of these countries, at least one religious or ethnic group is vying for dominance over the entire country, or to obtain some form of autonomy, as is the case with the Kurds in Iraq. In the Syrian case, with over 90% of the refugees who have left the country since the onset of the civil war in 2011 being Sunni Muslims, the Alawite regime has succeeded in increasing the proportion of Alawites among the population remaining in Syria from approximately 12% prior to the onset of the civil war to about a third a decade later (Kleiman 2020; Winckler 2017; Nowrasteh 2015).

The fourth type of demographic threat derives from the age structure of the population. In countries with a youthful age structure—a result of many decades of much higher fertility rates than the replacement-level rate[1]—the threat lies in a very low labor force participation rate, as a large proportion of the population is below working age, resulting in a low breadwinners/dependents ratio. This situation will persist for at least three more decades, even if the fertility rate declines to the replacement-level rate due to “the demographic momentum” phenomenon.[2] Currently, this is the situation in Egypt, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the Middle East, as well as in all sub-Saharan African countries. In contrast, in countries with an old age structure resulting from fertility rates persistently below the replacement-level rate for an extended period, the demographic threat manifests as a low labor force participation rate. This is due to a large proportion of the population being above working age.[3] Additionally, there are escalating costs associated with providing health and welfare services to an increasingly aging population (Slobodchikoff and Davis 2021). This situation necessitates countries to accept an increasing number of migrant workers in order to maintain a reasonable breadwinners/dependents ratio.

At first glance, it seems that Israel has always clearly belonged to the third category, namely, facing a demographic threat due to a struggle between two different religious and ethnic groups, engaging in a zero-sum game on the same piece of land, while the solution of dividing the territory into two separate political entities is not acceptable to at least one of the rival communities.[4] In this context, parallels can be drawn between the Zionist–Palestinian struggle for the area west of the Jordan River and the struggle among various religious sects for dominance in Lebanon, the Sunni–Shiite struggle for control of Iraq, the Sunni–Houthi (Shiite) struggle for control over Yemen, and, to a certain extent, the struggle between Arab-Sunni rebels and the Alawite regime in Syria, which led to the onset of the civil war.

However, while the sense of demographic inferiority among the Zionist movement prior to the establishment of the State of Israel and even after it is understandable in light of the fact that the 1948 War did not end with peace agreements but rather by cease-fire agreements, it was supposed to diminish after the Oslo Accords, and even more so after the withdrawal from the Gaza Strip.[5] The main purpose of both was to achieve a “demographic separation” from the Palestinians in order to maintain a solid Jewish majority in the State of Israel (Wertman 2021).

Was this really the situation, and if not, why? Did the peace agreements with Arab countries, from Egypt (1979), Jordan (1994), to the Abraham Accords (2020), alongside the collapse of the “eastern front” following the elimination of Saddam Hussein’s regime, and the outbreak of the civil war in Syria, weakening the Syrian army, lead to a change in the traditional Israeli demographic concept of “growing as much as possible”? What were the consequences of the Israeli demographic policy in both areas of the Law of Return and the desired fertility rate?[6] And finally, what are the external demographic threats to which Israel is exposed?

Changes in the Israeli Demographic Discourse: From Deficit to Appetite

Since the balance between the number of Jews and Arabs in the area of Mandatory Palestine was perceived by both sides as a zero-sum game, it was clear that without a critical mass of Jews in the territory they would not be able to realize their aim of establishing an independent political entity. From the beginning of the Mandate period, the Zionist leaders did everything they could to increase the Jewish population of Palestine through immigration, both legal and illegal, and by encouraging higher fertility among the Jews (Rosenberg-Friedman 2023). In order to prevent an increase in the number of Jews in Palestine, the Palestinian leaders did everything they could to limit Jewish immigration to Palestine and their ability to purchase land (Kimmerling and Migdal 1999).

Since the 1948 War ended only with cease-fire agreements and not with peace treaties, the debate regarding the balance between Israeli Jews and the populations of Arab countries, especially those hostiles to Israel and the Palestinians, only intensified, even after the establishment of Israel (Winckler 2022; Tal 2016; Rosenberg-Friedman 2015). In the publications of the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) to the present day, distinctions in the demographic data are made not only on the basis of religion but also between Jews and Arabs as two separate national sectors. The National Insurance Institute (NII) publishes data on poverty only on the basis of Jews and Arabs, and not on the basis of religion (Endeweld et al. 2022, 11, Table 4).

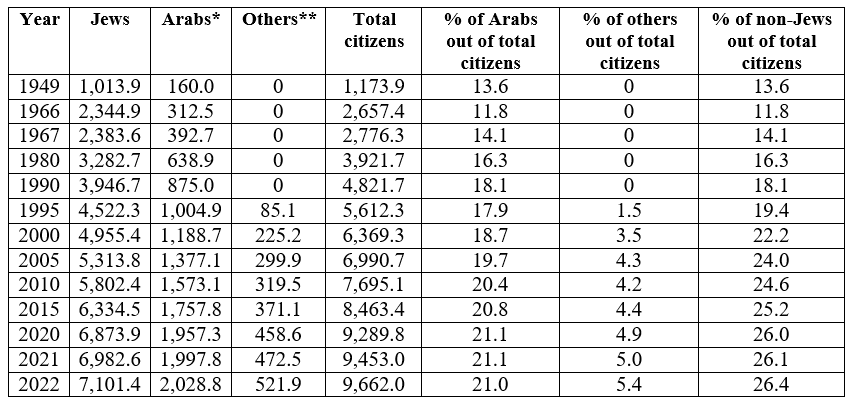

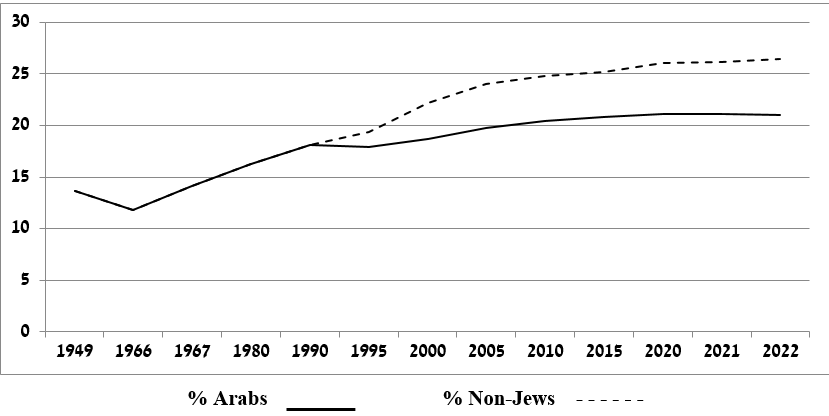

The slowdown in the pace of immigration to Israel after the October 1973 War until the start of the large immigration from the Soviet Union at the end of 1989, as well as the high natural increase rate of the Israeli Muslims,[7] led to a constant increase in the proportion of Arabs among the total Israeli citizens—from 11.8% at the end of 1966[8] to 18.1% in 1990 (see Table 1).

Table 1. The Composition of the Israeli Population by Religion and Nationality, 1949–2022 (end of the year population, in thousands)

* The category “Arabs” includes Muslims, Arab Christians, and Druze.

** The category “Others” includes members of other religions (Buddhists, Hindus, and more) as well as citizens who are not classified as either Jews or Arabs in the Population Register (“eligible for the Law of Return”). Until the 1995 census, “Others” were included in the Arab population.

Source: CBS, 2023d, Table 2.1.

Figure 1. The Proportion of Arabs and “Others” Among Israeli Citizens, 1949–2022 (%)

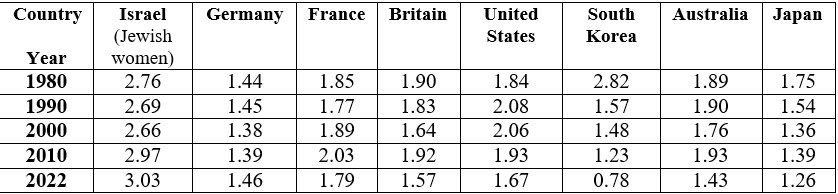

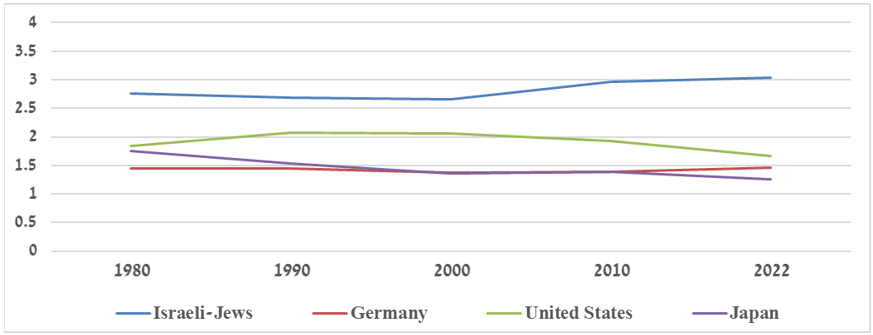

The perceived demographic vulnerability, whether in comparison to hostile neighboring countries or concerning the number of Arabs “west of the Jordan River,” has prompted Israeli governments, regardless of political orientation, to enact policies aimed at increasing as much as possible the Israeli Jewish population. From 1970 to 1996 the child allowances for the children of ex-servicemen and women were substantially higher than for children whose parents had not served in the security forces. For the children of new immigrants who had not served in the army, the difference between the normal child allowance and that of children of army veterans was funded by the Jewish Agency. The aim, of course, was to encourage higher fertility among the Jews (Ofir and Eliav 2005; Doron 2005; Winckler 2022). While the fertility rate in all industrialized countries, without exception and despite the various economic benefits given to large families,[9] fell continuously from the 1970s, the fertility rate among Israeli Jewish women increased to 3.03 in 2022—double the average in the European Union countries (see Table 2).

Table 2. Total Fertility Rate in a Number of Industrialized Countries and Israeli Jewish Women, 1980–2022\

Sources: Central Bureau of Statistics 2023b; World Bank, n.d.a.

Figure 2. Total Fertility Rate in a Number of Industrialized Countries and Israeli Jewish Women, 1980–2022

The peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan, the Abraham Accords, the thawing of relations with other Gulf oil countries, along with the ongoing instability in Iraq and the deterioration of Syria to the point where it no longer constitutes a military threat to Israel, as well as the establishment of the PA and the withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, were all expected to change the demographic discourse in Israel. Not only was Israel no longer militarily threatened by its neighboring Arab countries, but it was also apparently no longer demographically threatened in the area “west of the Jordan River” since the Palestinians, according to the Oslo Accords at least, were supposed to set up a separate political entity. Moreover, the large influx of immigrants from the former Soviet Union,[10] coupled with the ongoing decline in the fertility of Israeli Muslims,[11] as well as the increased fertility rate among Israeli Jews (see Table 2), halted the rise in the proportion of Arabs in the Israeli population. From 2010 to 2022, the percentage of Arabs in the Israeli population grew by only 0.6%—from 20.4% to 21.0% (see Table 1).

Therefore, in the absence of a demographic threat from the hostile countries and the Palestinians “west of the Jordan river,” and considering the economic deterioration since the onset of the Second Palestinian Intifada (al-Aqsa Intifada) in September 2000, as well as the burst of the “dot-com bubble,”[12] it was necessary to reduce child allowances and other financial benefits for large families. Indeed, from 2002 and even more so after the second Sharon government came to power in early 2003, child allowances for larger families were sharply cut. Although there have been several changes since then, child allowances and tax credits for children form only a small percentage of household income in middle-class households (Winckler 2022). In December 2023, the aggregate allowance for the first three children was only ILS 578 (NII n.d.).

Indeed, the sharp cuts in child allowances and in the other economic benefits for large households were among the main factors leading to a dramatic drop in the fertility rate among Israeli Muslims, particularly the Bedouin in the Negev, whose fertility rate fell from over 10 children per woman at the end of the 20th century to 4.99 in 2022 (CBS 2023d, Table 2.39).[13] In 2022, apart from the southern region, the fertility of the Israeli Muslims was less than three children (CBS 2023c; CBS 2023d, Table 2.39). Among Christian Arabs[14] and Druze, the fertility rate fell below the replacement-level rate (2023d, Table 2.41).

In 2016, Alon Tal (2016, 137) wrote that “With such high subsidies, there is great economic logic to having many children.” However, among Israeli Jews, even though the child allowances and other benefits in kind given to large families were sharply reduced, [15] the fertility rate among the Ultra Orthodox—the poorest sector among the Israeli Jews—only fell slightly.[16] This was partly due to the channeling of economic benefits to this sector other than child allowances, such as discounts on municipal taxes according to the number of people in the household (and not according to the per capita income of the household), special economic assistance to married yeshiva students, both from the yeshiva where they studied and from the Ministries of Education and Religions (Ministry of Education 2023), and more recently special food vouchers (Arlosoroff 2023). It should be noted that the fertility rate among non-religious Jewish women did not decrease even after the sharp cuts in child allowances.[17]

The main question that arises from these figures is why did Israeli governments, even in periods of deep economic recession, not change their demographic policies and try to slow down the rate of the population growth among Israeli Jews? Why even now, in 2024, when Israel’s population is groaning under a rising cost of living, alongside the enormous economic damages of the war in Gaza (Operation Swords of Iron) and high interest rates that affect monthly mortgage payments[18]—the highest single expense for a large percentage of households—no party is proposing to adopt the “Singaporean model,” namely full state funding for the first two children only, with costs passed to the parents from the third child onward in the form of high taxes (Lee et al. 1991).

It should be noted, however, that the lack of attempts to slow down the growth rate of the Israeli Jewish population was expressed not only by the almost complete absence of a debate on the anomalous fertility rates of Israeli Jewish women and all that entails (as we shall see later), but also by the fact that there has been no change to the Law of Return,[19] even though since the mid-1990s many immigrants, and during the past decade, the overwhelming majority of them, do not meet the definition of “Jew” (Nachshoni 2019). In 2020, only 28.3% of all immigrants from the former Soviet Union were registered as Jews, compared to 93.1% in 1990 (Eliyahu 2022, Figure 1). During 2021 alone, the number of “Others” rose by almost 50,000, and since 1995, when CBS began to publish data on this sector, the population of “Others” has increased at a faster rate than any other religious sector in Israel (Table 1). Why, in response to Tomer Moskowitz,[20] expressing that “the Law of Return should be amended” to remove the grandchild clause (allowing the law of return of those who are a grandchild of a Jew), did two Knesset members from the Yisrael Beiteinu party[21] immediately submit a complaint against him to the minister of the interior and the prime minister for “exceeding his authority”? (Rubin 2022). In the context of the desirable natalist policy for Israel, Trajtenberg et al. (2018, 9) wrote: “For the Israeli political system, any deviation from the premise that ‛children are a blessing’ still amounts to heresy.”

The answer to this question apparently lies in a number of processes occurring over the past two decades that led to a new perception of the nature of “the demographic balance west of the Jordan River”: The first and, in my opinion, the more prominent was the outbreak of the Second Intifada. Unlike the First Intifada, this one was accompanied by numerous terror attacks in Israel itself, including high-trajectory shooting fire from the Gaza Strip into Israel. Operation Defensive Shield (March–May 2002) only reinforced the feeling among the Israeli Jewish public that the PA under Arafat’s control was “not a partner for peace.” Arafat’s successor, Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen) was perceived from the outset as weak and thus deemed incapable of making decisive political moves. This feeling grew stronger after Fatah lost to Hamas in the elections of January 2006 for the Palestinian Legislative Authority. The failure of the Olmert–Abu Mazen negotiations (September 2006–December 2008) further added to this feeling, both among Israel’s political leadership and the general public, that it is at least currently impossible to end the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Indeed, Benjamin Netanyahu repeated many times that “there is no Palestinian partner for peace” (Benziman 2018).

The takeover of the Gaza Strip by Hamas in June 2007 essentially created a separate political entity distinct from both Israel and the PA. This occurred alongside the growing notion within Israel that “there’s nobody to talk with,” collectively shaping a new “demographic equation”—the numerical balance between Jews and Arabs “west of the Jordan River.” However, in contrast to the past, this equation no longer includes the Gaza Strip, and even following the onset of the Swords of Iron War, very few in Israel’s political elite or among the general public support the renewal of Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip (Ciechanover, 2023).

“The Million Person Gap: The Arab Population in the West Bank and Gaza” by Zimmerman et al. (2006) provides evidence for supporters of annexing all or part of the West Bank to Israel. Its main conclusion is that the number of Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip is considerably less than the number given in the official Palestinian publications. According to the findings of Zimmerman et al., the actual number of Palestinians in the West Bank (not including East Jerusalem) and Gaza Strip was 2.47 million in early 2004: 1.4 million in the West Bank and 1.07 million in the Gaza Strip. These figures are strikingly lower than the official Palestinian figures. In view of these findings, it is clear that Israel’s fears of demographic pressures from these areas were largely exaggerated.

Opponents of the “two state solution” have frequently cited this research since its publication.[22] This is because it supports the feasibility of annexing all or part of the West Bank to Israel without jeopardizing the Jewish majority “west of the Jordan River.” Eldad (2016), for example, wrote, “Anyone who relies on the Palestinian CBS data in order to determine whether there are more Arabs than Jews west of the Jordan River, and thus influence decision makers, is relying on propaganda, not science.” Therefore, once the Gaza Strip is removed from the demographic equation following the unilateral withdrawal, the demographic balance “west of the Jordan River” increasingly favors the Jews. Since the CBS includes the “Others” with the “Jews by nationality” in the national demographic equation,[23] and the majority of them vote for right-wing parties,[24] the continuation of the Law of Return in its current format not only increases the proportion of “Jews by nationality” within Israel’s existing borders, but also preserves a solid Jewish majority “west of the Jordan River.” It goes without saying that the larger the Jewish majority between the Jordan River and the sea, the better. In light of these circumstances, it is easy to understand why there is a focus on encouraging high fertility among Israeli-Jewish women and a reluctance to change the Law of Return (including the “grandchild clause,” which effectively includes the fourth generation), especially since immigration from the industrialized countries, where most Jews living outside Israel are concentrated,[25] is very low. In 2022, out of 74,714 immigrants to Israel, only 7.0% (5,163) came from the United States and France—the two largest concentrations of Jews outside Israel (CBS 2023a).

East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights as a Precedent?

Without a political decision regarding the future of the West Bank, along with the economic advantages for Israeli citizens living there, such as significantly lower housing costs, tax benefits, and better quality public services (Macro 2016; Melnitchi 2019), as well as the proximity to Israel’s main employment centers, living beyond the Green Line is perceived as the most accessible solution for improving the quality of life, especially for young couples. Indeed, even after the signing of the Oslo Accords, the Jewish population in the West Bank continued to grow rapidly. By January 2022, nearly 492,000 Israeli citizens were living in these areas (Yesha Council 2022), compared to 116,340 at the end of 1993 (CBS 1994, Table 2.13), right after the Oslo Accords were signed. While the Israeli “Jews and Others” population grew by 69% from 1993 to 2021 within Israel, the Israeli Jewish population in the West Bank increased by a factor of 4.2 (CBS 2022a, Table 2.1). In 2021 alone, the number of Israeli citizens living in the West Bank rose by 16,000 (Yesha Council 2022), representing a 3.3% increase—nearly double the growth rate of the Israeli Jewish population. Assuming that the annual growth rate of the Jewish population in these areas remains at 3.3% in the medium term due to positive migration and a high fertility rate,[26] the number of Israeli citizens in these areas will increase by another 170,000 in one decade reaching about 700,000 by the end of the next decade. If the Shomron Regional Council’s “One million residents in Samaria by 2050” program (Shomron Regional Council n.d.) is realized, even partially, and housing prices within the Green Line—especially in the country’s center—continue to rise, demand for housing in the West Bank will likely increase, attracting more Jewish residents to the area.

Alongside the rapid growth of the Israeli population in the West Bank and its dispersal throughout the territory (Arieli, 2022), there has been a gradual process of economic integration between the Israeli and PA economies. This integration has led to increasing mutual dependency, which is evident in the following five areas:

(a) The PA’s heavy dependence on taxes collected by Israel: The Paris Protocol (April 1994) established a customs union between Israel and the PA, allowing Israel to collect indirect taxes for the PA, including import taxes, excise,[27] and VAT, and 75% of all direct taxes collected from Palestinians employed in Israel (after deducting commission and collection charges). Since the establishment of the PA, these taxes have accounted for at least two-thirds of its budget. The remaining third largely consists of donations that have steadily declined—from over 20% of the PA GDP in 2008 to 10% in 2013 and to only 1.8% in 2021—about a billion NIS (IMF 2023)—due mainly to the sharp drop in US aid during the Trump presidency and other international aid (Bossa et al. 2020). The PA’s revenues from fees and local direct taxation account for only a small percentage of its total revenue (Michael and Milstein, 2021).

(b) Mutual employment dependence: Despite the option of importing foreign workers for the construction industry, Israeli contractors have preferred to hire Palestinians. This preference for Palestinian workers is because the contractors do not have to arrange accommodation and health insurance, which significantly increases the cost of employing foreign workers. The state also has favored the employment of Palestinians rather than foreign workers for two main reasons: First, the Palestinians do not live in Israel and therefore do not consume public services (health, education for their children, and so forth), nor do they contribute to the demand for housing in the major employment centers. Second, the security services maintain that extensive employment of young Palestinians in Israel reduces their motivation to commit acts of terror against Israel (Bohbot 2023; Zubida 2023). Indeed, since 1967, the Israeli residential construction industry has heavily relied on Palestinian employees. According to Bank of Israel data, in 2022, 177,300 Palestinians were employed in Israel, of whom 95,900 worked in the construction industry, representing 28.5% of all employees in the sector (Bank of Israel 2023, Tables H-N-3, B-N-35). Additionally, another 44,000 Palestinians were employed illegally in Israel, and about 40,000 worked in the Israeli settlements in the West Bank (Etkes and Adnan 2022). Therefore, more than half of all workers in the PA area were either directly employed in Israel and the Israeli settlements in the West Bank, with or without permits, or in the PA public sector, which, as stated above, is funded mainly by taxes collected by Israel. The paralysis that gripped Israel’s housing and infrastructure sector due to restrictions on the employment of Palestinians in Israel, following the outbreak of the Swords of Iron War, illustrates the mutual employment dependence between Israel and the PA.

(c) Foreign trade: The PA’s foreign trade, both import and export, is almost entirely conducted with Israel in NIS, rather than in foreign currency, which allows the PA to avoid holding foreign currency reserves. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Israel was the destination for about 80% of all Palestinian exports, worth about 3 billion NIS per annum (Shusterman 2020). Since the end of the pandemic, this figure has increased to about 90% in 2021 (U.S. Department of State 2022; IMF 2023).

(d) Water supply: Due to its limited natural water resources, the PA cannot rely solely on its own water sources. However, unlike other Middle Eastern countries, the PA (excluding the Gaza Strip) does not have access to the sea, making it unable to utilize desalination. As a result, the PA is entirely dependent on water from Israel.[28] With the PA’s rapid population growth, coupled with the ongoing climate crisis causing a decrease in precipitation across the eastern basin of the Mediterranean Sea, this reliance on Israel is expected to increase. According to data from the Water Authority, Israel supplied the PA with 76 million cubic meters of water in 2021.[29]

(e) Electricity supply: The PA does not have any electricity power stations in the West Bank. Apart from a small amount of electricity produced by solar panels, Israel generates all electricity in the West Bank.

The PA’s economic dependence on Israel was described by Arie Arnon as follows: “The existence of ‛Palestine’ as a united, independent and separate economic entity is a fiction […]. Fifty-four years of Israeli control have erased the border between Israel and the Palestinians—not just the physical border but the economic border as well” (Goldstein 2021). The Israeli population in the West Bank, which stretches from the Jordan Valley in the north to beyond Mount Hebron in the south, combined with the mutual dependence of the two economies, means that the feasibility of a physical separation between Israel and the Palestinians on the West Bank is continually shrinking.

At the same time, at least up to this point, when Israel annexed territory and subjected it to Israeli law, the non-Jewish residents gained permanent residency status. This was the case in East/Arab Jerusalem in 1967 and also for the Druze residents of the Golan Heights after the Golan Heights Law was passed in December 1981. In addition to the security issues arising from the free movement of West Bank Palestinians within Israel, which is permitted for all permanent residents, consolidating the territory west of the Jordan River into one political entity would have significant economic consequences, which have received little attention until now. Even before the pandemic severely harmed the PA economy, its per capita GDP was one-eighth that of Israel (Bossa et al. 2020). Since the residents of the PA (the West Bank, excluding East Jerusalem) are equivalent to about a quarter of the Israeli citizens,[30] combining the two economies into one would cause a dramatic drop in Israel’s per capita GDP. Moreover, granting permanent residency status to the PA population would significantly increase the burden on Israel’s public services, particularly welfare, health, and education. As we will see below, these services already struggle to meet the standards expected of an OECD economy.

Apart from the steep decline in the standard of living for Israel’s citizens, if the territory of the PA is annexed wholly or in part, the Israeli regime will have to change accordingly. In this context, Peri (2016, 114) argued that “the Israeli Jews will not allow Palestinians to be equal partners in running the country […]. In this situation, the inevitable outcome will be a significant decline in Israeli democracy.”

In contrast, the establishment of an independent Palestinian state with control over its own borders poses a threat to Israel, both in terms of security and demographically, especially if the borders are opened to Palestinian refugees or even to citizens of adjoining Arab countries facing severe economic crises, particularly Lebanon and Syria. This danger is not merely hypothetical. In September 2015, prior to the UN General Assembly meeting, Abu Mazen requested that Palestinian refugees from Syria be permitted to enter “Palestine” (i.e., the West Bank) given the ongoing civil war in Syria (Channel 20, 2015). For Israel’s preferred option—annexing part of the territory according to Trump’s “deal of the century” (Sher 2020)—there was not a single Palestinian partner, while Jordan rejected it outright (Issacharoff and Itiel 2020). Regardless, since the end of Trump’s presidency, this plan has become irrelevant.

The Impact of the “Growing as Much as Possible” Policy on the Quality of Life in Israel

Israel’s unprecedented rapid population growth and its young age structure[31] have significant consequences, some of which are irreversible in the short and medium term. The main ones are as follows:

(a) A Low Breadwinners/Dependents Ratio: Studies of the demographic history of industrialized countries show that their most significant economic leap forward occurred during a period of “demographic gift” (or “demographic dividend”)—a period when at least 70% of the population was of working age (20–64) and the economic activity rate[32] of both men and women was high. Even though this period is temporary, lasting only three to four decades (in accordance with the age structure), it provides the necessary timeframe for economic advancement. This is because during this period, not only is the ratio of breadwinners to dependents optimal, with a small proportion of people below and above working age, but the country can also allocate resources from education, health, and welfare services to areas that promote rapid economic growth, such as physical infrastructure, scientific research, and technological development. The “Asian Tigers”[33] during the 1960s and 1970s are the best example of the contribution of the demographic gift age structure to rapid economic development (Madsen et al. 2010).

In Israel, however, due to the high fertility rate, the population under the age of 20 has increased rapidly.[34] Israel also faces a specific problem that hinders improvement in per capita income—a very low labor force participation rate for ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) men (56%) and Muslim women (45%)[35] (CBS 2022b; Peleg-Gabai 2022; Eretz 2023). It should be noted that not only is the labor force participation rate of ultra-Orthodox men substantially lower than the average rate of Israeli men, but many of them are also employed within their own community as teachers in schools and yeshivas. Additionally, a significant percentage of them do not work full-time. Among Muslim women, the rate of full-time employment is lower than the average for all Israeli women (Malach and Cahaner 2022; Ministry of Labor 2023).

The combination of a significant portion of the population being below working age, coupled with low labor force participation rates among ultra-Orthodox men and Muslim women—two sectors with much higher-than-average growth rates—contributes to an overall low labor force participation rate for the entire country. Indeed, Israel’s overall labor force participation rate is 7%–8% lower than that of most other OECD countries (World Bank n.d.b; n.d.c).

(b) Deterioration of public services: The rapid population growth has led to an increase in demand, contributing to a decline in the quality of public services. One of the clearest expressions of this is in healthcare: by the end of 2020, the number of hospital beds per capita was 8% lower than a decade previously (Hillel and Haklai 2021), placing Israel among the countries with the lowest rates in the OECD (Chernichovsky and Kfir 2019). As population growth continues to outpace the expansion of health infrastructure, education, law enforcement, and welfare services, the quality of these services and the overall standard of living continue to deteriorate.

(c) Overcrowding: Overcrowding is particularly evident along the coastal plain where most of Israel’s population is concentrated. Attempts by various governments to disperse the population, mainly to the Negev and Galilee—through generous economic incentives such as significant tax cuts—have had only limited success. This is largely due to the lack of an advanced transport infrastructure and suitable public services (Kahana 2022; Rosner 2023). In addition, the IDF’s need for extensive areas in the Negev for bases and firing zones further complicates the relocation of large numbers of people to the region. The result is steady overcrowding along the coastal plain, leading to rising air pollution and violence. This overcrowding is a major factor in the decline in the quality of life. Simply observing the continuously growing commute time between and within major employment hubs reveals that overcrowding not only diminishes the quality of life but also increases living expenses. This includes the time wasted on commuting, along with associated travel costs. Moreover, it disregards expenses such as childcare for parents with young children and other additional costs resulting from longer commuting times.

(d) Rising cost of living: One of the most pressing concerns is the rising cost of living, particularly concerning items that cannot be imported, primarily land for housing construction. Several factors have contributed to the dramatic rise in housing prices in Israel since 2008, including the reduction of interest rates to only 0.1%, which lowered borrowing costs; the slow marketing of land; bureaucratic complexity in planning committees; and more. However, the main factor is the widening gap between supply and demand, which has risen by about 2% annually due to population growth (Brezis 2021). In addition to rapid population growth, the increasing divorce rate has also contributed to the demand for housing.

(e) Perpetuation of high poverty rate:[36] The likelihood of poverty naturally increases with the size of the household, meaning that a high proportion of large families inevitably leads to a higher incidence of poverty. In July 2023, fourth and subsequent children accounted for 14.4% of all children in Israel (NII 2023, Table 6.3.1). Of all households that received child allowance, 17.7% received the allowance for four or more children, and 8.6% for five or more children (NII 2023, Table 6.2.1). In 2019, even before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the poverty rate among households with four or more children was 45.2%, rising to 55.6% among families with five or more children (Endeweld et al. 2021, 15, Table 4). In view of this data, it is clear why the incidence of poverty among children in Israel reached 28.7% in 2020 (Endeweld et al. 2022, 10, Figure 2). As long as the fertility rate does not decline and the proportion of children living in households with six or more people remains high, the poverty rate in Israel will remain above 20%, even with substantial increases in child allowances.

External Demographic Threats

The external demographic threats to Israel—those beyond its direct control—can be divided into three main categories based on different timeframes:

(a) The short term: Refugee influx: Since the end of 2019, the Lebanese economy has almost ceased to function, with recent reports from Lebanon describing almost total chaos. According to the Fragile States Index, Lebanon ranks 29th,[37] similar to Venezuela and Iraq (Fund for Peace 2022), both of which have already “exported” large numbers of refugees to neighboring countries. Given the ongoing political deterioration in Lebanon, with no foreseeable solution, and its hosting of approximately 1.5 million Syrian refugees—over a quarter of its population (Yasin 2023)—it is plausible to anticipate a potential influx of Lebanese refugees seeking safety in neighboring countries, including Israel.

A similar threat of incoming refugees, particularly Druze, exists along Israel’s border with Syria. Although the civil war in Syria ended some time ago, the rebuilding process has yet to commence. As a result, Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan, and certainly those who fled to Europe have not returned to Syria.[38] Any worsening conditions, especially in southern Syria, could prompt refugees to cross the border into Israel.

However, the greatest and most immediate risk of an influx of refugees to Israel comes from the Gaza Strip, home to about 2.2 million people, with a natural growth rate of almost 3% annually (PCBS 2022)—doubling in size in just three decades. As a result of the war in Gaza, almost the entire population of the Gaza Strip has become displaced. Egypt has consistently refused to open its border to provide refuge for fleeing residents of Gaza.

Even under optimal conditions, can the Gaza Strip’s economy support such a large population? It is very doubtful. Therefore, in a situation of a humanitarian disaster, which becomes increasingly likely as the war continues, refugees from the Gaza Strip will naturally seek refuge in Israel. And Israel, like any other democratic country, has no solution for refugees arriving at its borders but to provide humanitarian aid. When discussing Palestinian refugees from the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, Lebanon, or Syria in the context of Israel, the issue involves not only humanitarian concerns but also, and perhaps more importantly, politics and security.

(b) The medium term: Greater pollution: Israel is already in the unflattering 57th position (out of 180 countries) on the EPI (Environmental Performance Index), placing it lower than nearly all other OECD countries (Wolf et al. 2022). Rapid population growth will require the construction of more power stations and water desalination plants, leading to a rise in air pollution—even if new facilities are built and operated according to the strictest standards. Furthermore, Israel supplies water not only to itself but also to the PA, the Gaza Strip, and Jordan, whose populations are also growing rapidly; this will significantly increase the demand for desalinated water in Israel. Israel has another environmental problem—its proximity to the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. In these areas, levels of air pollution are higher and likely to rise in the future. This increase is not only due to rapid population growth but also to the failure to enforce environmental quality standards, which Israel cannot impose in these areas, since it does not formally control them. The rising air pollution is already affecting the air quality in Israel, and this will continue, particularly in areas close to the Green Line (Assayag, 2023).

(c) The long term: The climate change consequences: Global warming affects Israel in three main areas. The first is the expansion of desertification, a critical issue for a semi-arid country like Israel. Increasing desertification will harm agriculture and even reduce precipitation, forcing Israel to desalinate much larger quantities of water—due not only to rapid population growth but also to declining rainfall. Second, global warming has already led to flooding, especially in the densely populated coastal plain. Forecasts indicate that flooding will become more frequent, not only due to changes in rainfall caused by global warming but also because the increasing population pressure means fewer open areas that can absorb runoff water. Even today, the coastal plain, from Ashkelon in the south to Nahariya in the north, is effectively one continuous urban space. Third, Israel’s location on the seam between Asia and Africa could expose it to not only political refugees from neighboring areas but also to climate refugees from Africa. It should be remembered that Israel is already hosting tens of thousands of refugees from failing African countries (Michael et al. 2021).

What Next?

Although Israel’s rapid population growth affects all areas of life—from skyrocketing housing prices to deteriorating environmental quality, growing congestion on the roads, rising violence, and the ever-growing cost of living—the subject of the desirable fertility rate for Israel remains an “absent presence” in the public, professional, and political discourse. What makes Israel unique is that even without significant financial incentives, the fertility rate of the middle class is almost double the average in OECD countries. This is driven by the victory of the “Zionist demographic ethos.” However, unlike economic changes, demographic shifts occur slowly over many decades. Even if the current fertility rate is controlled, Israel, already overcrowded, would still experience increased population due to the phenomenon of the “demographic momentum,” with significant implications for its standard of living.

Although any change to Israel’s demographic policy, whether regarding the desirable fertility rate or the Law of Return, is an internal decision, it requires broad national consensus. As of the time of writing in early 2024, achieving a general consensus on such a sensitive issue seems impractical, given the wide divergence of views among the different sectors of Israeli Jews on this issue and others.

In addition to the “domestic demographic danger” posed by rapid population growth, the “two-state solution” is becoming ever more distant as the Israeli population in the West Bank continues to grow rapidly. Contrary to the common perception that Israel controls the future of the West Bank, preventing the creation of one state “west of the Jordan River” is something that Israel cannot do unilaterally; it requires a settlement with the PA, whether the existing one or any future version that may emerge after the war in Gaza. At present, the PA is widely seen as incapable of making any decisions, let alone implementing them, on reaching a settlement with Israel, whether concerning the West Bank alone or including the Gaza Strip in the post-war period.

What will be the outcome of the ongoing process of Israel’s integration with the West Bank? How will this process affect the standard of living in Israel? What resources will be required to protect the growing Israeli population in the West Bank, and how will this security be achieved? When and under what circumstances will Israel’s rapid population growth become unsustainable? Only time will tell.

References

Abusrihan, Naser, and Jon Anson. 2021. “The Decline in Fertility in Bedouin Society of the Negev in the 21st Century.” Social Security 114, 25–59 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/3t2dnzj.

Arieli, Shaul. 2022. Are They Holding Land or Fooling Us? The Influence of Jewish Settlements in Judea and Samaria on the Feasibility of the Two-State Solution Tiktakti-Digital Publishing (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2e99pm5b

Arlosoroff, Meirav. 2023. “Not Just Food Vouchers: The City Tax Discounts Are also Tailored for the Haredim.” The Marker, August 15 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2bxh2rjr.

Assayag, Tomer. 2023. “It’s a Chemical Attack: It’s Impossible to Breathe’: The Smoke from Palestinian Incinerators Harms Israel.” Ynet, July 15 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/muztrajz.

Bank of Israel. 2023. Statistical Appendices and Supplementary Data: Bank of Israel Annual Report—2022. March 23 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yw6cy3p5.

Benziman, Yuval. 2018. “The Attempt by the Netanyahu Government to Separate Israeli-Arab Relations from the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process.” Mitvim Institute (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/ru46smft.

Bohbot, Amir. 2023. “The Security System Is Considering Granting Work Permits in Israel to Thousands of Young Palestinians.” Walla!, September 4 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/y2k5j3y2.

Bossa, Yann, Ruth Hanau Santini, Robi Natanzon, Paul Fash, and Yanai Weiss. 2020. “The International and Domestic Economic Consequences for Israel of a Possible Annexation of the West Bank.” IEPN, July 27 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/pknmkkst.

Brezis, Alice. 2021. “The Main Reason for the Rise in Housing Prices Is the Population Explosion.” Globes, November 10 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2hxn2pm4.

Calcalist. 2015. “Merkel: Our Economy Is Healthy, There Is no Limit to the Number of Refugees We Can Take In.” Calcalist, September 5 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yefv8m5e.

CBS (Central Bureau of Statistics). 1994. Statistical Abstract of Israel 1994, No. 45 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/566htw72.

CBS. 2001. Statistical Abstract of Israel 2001, No. 52 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/mr2aa7de.

CBS. 2016. “Selected Data on Immigrants from the Former USSR Marking 25 Years Since the Immigration Wave.” Press release, April 5 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/4yjxdd9h.

CBS. 2020. “Fertility of Jewish and Other Women in Israel, by Degree of Religious Observance, 1979–2019.” November 16, written by Ahmad Halihel (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/68dvcyrk.

CBS. 2021a. Statistical Abstract of Israel 2021, No. 72 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/mwcwbt42.

CBS. 2021b. Christmas 2021—Christians in Israel. Press release, December 21 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yyfyfpaa.

CBS. 2022a. Statistical Abstract of Israel—2022, No. 73 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/5hy63px4.

CBS. 2022b. The Muslim Population in Israel—2022. Press release, July 6 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/mrbj74jm.

CBS. 2023a. Immigration to Israel—2022. Press release, August 27 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2bn5mawd.

CBS. 2023b. “Total Fertility Rate by Mother’s Religion, 1949–2022,” (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/5aarjkyt.

CBS. 2023c. “Population in Settlements. Table 2.9: Live Births and Total Fertility Rate in Settlements with 10,000 or More People, 2022,” (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/3t6czbce.

CBS. 2023d. Statistical Abstract of Israel 2023, No. 74 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yd9ur8mb.

Channel 20. 2015. “Toward the UN Assembly: Abu Mazen Will Ask Israel to Accept Palestinian Refugees from Syria.” Ynet, September 6 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/39na5d2v.

Chernichovsky, Dov, and Roi Kfir. 2019. “The State of the Acute Care Hospitalization System in Israel: The Current Situation.” In State of the Nation—2019, edited by Avi Weiss. Taub Center (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/y53a8mnv.

Ciechanover, Yael. 2023. “A Return to Jewish Settlement in Gush Katif? Netanyahu Has Already Clarified: ‘Not a Realistic Objective.’” Ynet, November 12 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yc49d9aw.

Della Pergola, Sergio. 2007. “Demography: The Controversy Continues.” Tchelet 27, 7–21 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/vfmyeff6.

Doron, Abraham. 2005. “The Erosion of the Israeli Welfare State in the Years 2003–2005: The Case of Child Allowances.” Work, Society & Law 11, 95–120 (in Hebrew).

Eldad, Arieh. 2016. “The Big Demographic Lie: A Jewish Majority Is a New Phenomenon, That Is Not About to Disappear.” Maariv, October 8 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/58s4hex4.

Eliyahu, Ayala. 2022. “Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union Who Are Not Recognized as Jews and the Extent of Their Conversion in Israel.” Knesset Research & Information Center, August 4 (in Hebrew). https://katzr.net/368c58.

Endeweld, Miri, Lahav Karady, Rina Pines, and Nitza (Kaliner) Kasir. 2021. “Poverty and Income Inequality—2020.” National Insurance Institute (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/24sbf9d9.

Endeweld, Miri, Lahav Karady, Rina Pines, and Nitza (Kaliner) Kasir. 2022. “Poverty and Income Inequality—2021.” National Insurance Institute (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/252zkcap.

Eretz, Idan. 2023. “Significant Leap Forward in the Employment of Haredi Men and Arab Women.” Globes, August 2 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/327yekma.

Etkes, Haggay, and Wifag Adnan. 2022. “Undocumented Palestinian Workers in Israel: Did the Israeli COVID-19 Policy Boost Their Employment?” INSS Insight no. 1596, May 8 (in Hebrew). https://www.inss.org.il/publication/illegal-workers.

Eurostat. 2023. Population Structure and Ageing. http://tinyurl.com/yjadj2mp.

Even, Shmuel. 2021. “The National Significance of Israeli Demographics at the Outset of a New Decade.” Strategic Assessment 24 (3), 28–41. https://katzr.net/db644a..

Fund for Peace. 2022. Fragile States Index, 2022. https://fragilestatesindex.org.

Gavison, Ruth. 2009. “60 Years to the Law of Return: History, Ideology, Justification.” Metzilah Center (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/3jv9t57h.

Goldstein, Tani. 2021. “One Economy for Two Peoples.” Zeman Yisrael, November 28 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2fwye5t8.

Green, Shaked. 2023. “Following Interest Rate Rises: The Monthly Mortgage Repayment Has Increased by NIS 1,150 on Average Within a Year.” Calcalist, May 22 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/58dbwmv2.

Hillel, Stavit, and Ziona Haklai. 2021. “Hospital Beds and Positions in Licensing.” Ministry of Health, Information Department (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/33u64cza.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2023. “West Bank and Gaza—Selected Issues.” September 13, http://tinyurl.com/yc8e56yf.

Issacharoff, Avi, and Yoav Itiel. 2020. “Abu Mazen: ‘The Deal of the Century—A Plot That Will Not Pass’; Jordan Warns Against Unilateral Moves.” Walla!, January 28 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/dhhm8m3u.

Jewish Agency. 2023. “Eve of the New Year 57845: About 15.7 Million Jews in the World, of Whom 7.2 Million Live in Israel.” September 15 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/5arwm9yz.

Kahana, Ariel. 2022. “We’ve Reached the End; Without a Sharp Change of Direction, We Could Fall to Less Than 10% Jews in Galilee.” Israel Today, April 28 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2ax6rs8x.

Kimmerling, Baruch, and Joel S. Migdal. 1999. Palestinians: The Making of a People. Keter Books. (in Hebrew).

Kleiman, Shahar. 2020. “Millions of Refugees and the Picture of Victory: What Is Behind the Escalation in Idlib?” Israel Today, March 1 (in Hebrew). https://katzr.net/49e8e2.

Konstantinov, Viacheslav. 2022. “Immigrants From the Former Soviet Union and Elections in Israel: Statistical Analysis for 30 Years (1992–2021) – Updated Version.” Brookdale Institute (in Hebrew). https://jewstat.info/he/ha-alia/haalia-harusit.

Laitin, David D. 1995. “National Revivals and Violence.” European Journal of Sociology 36 (1), 3–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23999432.

Lee, Sharon M., Gabriel Alvarez, and J. John Palen. 1991. “Fertility Decline and Pronatalist Policy in Singapore.” International Family Planning Perspectives 17 (2): 65–69+73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2133557.

Macro Center for Political Economics, 2020. “Tracking Settlements: The Israeli Housing Market in the West Bank Compared to Other Parts of the Country.” October 30 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2s49s8nj.

Madsen, Elizabeth Leahy, Beatrice Daumerie, and Karen Hardee. 2010. “The Effects of Age Structure on Development: Policy and Issue Brief.” Population Action International. http://tinyurl.com/4t3kkj4h.

Malach, Gilad, and Lee Cahaner. 2022. Annual Statistical Report on Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) Society in Israel-2022. Israeli Institute of Democracy (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/4mjnb3wp.

Melnitchi, Gili. 2019. “Who Doesn’t Want a Large House with a Garden for a Million Shekels? The New Hit Among The Young.” TheMarker, November 15 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yxahtxjn.

Michael, Kobi, and Michael Milstein. 2021. “The Dream and Its Shattering and the Country That Does Not Exist: The Palestinian Failure to Realize the Goal of Sovereignty and Independence.” In Between Stability and Revolution: A Decade to the Arab Spring, edited by Elie Podeh and Onn Winckler (in Hebrew). Carmel.

Michael, Kobi, Alon Tal, Galia Lindenstrauss, Shira Bukchin-Peles, Dov Khenin, and Victor Weis, eds. 2021. Environment, Climate and National Security: A New Front for Israel. Memorandum 209. Institute for National Security Studies (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/arn7yscc.

Ministry of Education, Senior Division of Torah Institutions. 2023. “Assistance for Torah Students” (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/582yc8nn.

Ministry of Labor, Senior Division for Strategy & Policy Planning. 2023. “The Rise in the Employment Rate of Haredi Men in 2023” (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2s36v2xm.

Nachshoni, Kobi. 2019. “Revealed: 86% of the Immigrants to Israel Are Not Jews.” Ynet, December 23 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yckfed29.

NII (National Insurance Institute). n.d. “Calculation of Child Allowances” (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/38a2v7dr.

NII. 2023. “Children.” Monthly Bulletin of Statistics (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/44bmh2bj.

Nowrasteh, Alex. 2015. “Who Are the Syrian Refugees?” CATO Institute, November 19. http://tinyurl.com/39f9wsvd.

Ofir, Michal, and Tami Eliav. 2005. “Child Allowances in Israel: A Historical Glance and International View.” National Insurance Institute (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/4fhsws23.

PCBS (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics). 2022. “Estimated Population in Palestine Mid-Year by Governorate,1997–2021.” https://www.pcbs.gov.ps.

Peleg-Gabai, Merav. 2022. “Haredi Employment: Overview.” Knesset Research & Information Center, June 13 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/ch8mvup5.

Peri, Yoram. 2016. “Territorial Expansion and Social Disintegration.” In Israel 2048: Strategic Thinking for Planning and Development in the Area, edited by Shlomo Hasson, Oded Kutok, Doron Drukman and David Roter. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Shasha Center for Strategic Studies (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/y2m8nc6e.

Rosenberg-Friedman, Lilach. 2015. “David Ben-Gurion and the ‛Demographic Threat’: His Dualistic Approach to Natalism, 1936–1963.” Middle Eastern Studies 51 (5), 742–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2014.979803.

Rosenberg-Friedman, Lilach. 2023. Birthrate Politics in Zion: Judaism, Nationalism, and Modernity Under the British Mandate. Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism (in Hebrew).

Rosner, Shmuel. 2013. “Judaizing Galilee: The Demography Is Clear, All the Rest Is Subject to Controversy.” Kan 11, June 12 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yth8yd73.

Rubin, Bentzi. 2022. “Complaint Filed Against the Director General of the Population and Migration Authority: ‘Exceeding His Authority.’” Srugim, August 4 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/ywnbuyc9.

Sasson, Yitzhak. 2022. Who Is a Jew? The State Is Trying to Give Two Different Answers to One Dramatic Question. Ha’aretz, August 17 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2mx5yyd2.

Shavit, Uriya. 2022. The Other Germany: The Refugee Crisis and Angela Merkel. Tabur, no. 11. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (in Hebrew). https://tabur.huji.ac.il.

Sher, Gilead. 2020. “Comparing the ‘Deal of the Century’ With Previous Plans.” INSS Insight no. 1255, February 2. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/trump-deal-comparative-review/.

Shomron Regional Council. n.d. Shomron Regional Council Presents: A Plan for a Million Residents in Samaria by 2050 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/mupmvmtr.

Shubert, Atika, and Nadine Schmidt. 2019. “Germany Rolls Up Refugee Welcome Mat to Face Off Right-Wing Threat.” CNN, January 26. http://tinyurl.com/cnd5hkaa.

Shusterman, Noa. 2020. “The Palestinian Authority: The Economic Challenge Following COVID-19.” INSS Insight no. 1320, May 20. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/the-pa-economic-situation-after-corona/.

Slobodchikoff, Michael O., and Gregory D. Davis. 2021. “The Demographic Threat.” In The Challenge to NATO: Global Security and the Atlantic Alliance, edited by Michael O. Slobodchikoff, Gregory D. Davis, and Brent Stewart. University of Nebraska Press.

Sofer, Arnon, and Yaniv Gambush. 2007. The Illusion of the Million Gap: Response to “The Million Gap: The Arab Population in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (in Hebrew). University of Haifa, Haikin Chair of Geostrategy.

Tal, Alon. 2016. The Land Is Full (in Hebrew). Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

Trajtenberg, Manuel, Rachel Alterman, Dan Ben David, Dan Perri, Shlomo Bekhor, Shira Lev Ami, et al. 2018. A Crowded Future: Israel 2050. Zafuf (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2c6s37tz.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2023. “Syria Refugee Crisis Explained.” March 14. http://tinyurl.com/2p9v4spu.

Uni, Assaf. 2020. “Is Europe Surrendering? Erdogan Will Receive Another Half Billion Euros to Prevent the Passage of Refugees.” Globes, June 18 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/2ph54mhy.

U.S. Department of State. 2022. 2022 Investment Climate Statements: West Bank and Gaza. http://tinyurl.com/7vsmre9t.

Walker, Shaun and Flora Garamvolgyi. 2022. “Viktor Orbán Sparks Outrage With Attack on ‛Race Mixing’ in Europe.” The Guardian, July 24. http://tinyurl.com/7kmk6ekt.

Wertman, Ori. 2021. “The Securitization of the Bi-National State: The Oslo Accords, 1993–1995.” Strategic Assessment 24 (4), 23–38. https://katzr.net/e30d06.

Winckler, Onn. 2008. “The Failure of Pronatalism of the Developed States ‛With Cultural-Ethnic Hegemony’: The Israeli Lesson.” Population, Place and Space 14 (2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.476.

Winckler, Onn. 2017. Arab Political Demography. 3rd edition: Sussex Academic Press.

Winckler, Onn. 2022. Behind the Numbers: Israel Political Demography (in Hebrew). Lamda Iyun.

Wolf, Martin J. et al. 2022. Environmental Performance Index 2022. Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy. http://tinyurl.com/54z4a8et.

World Bank. n.d.a. “Fertility Rate, Total (Births per Woman).” http://tinyurl.com/bj45rxdn.

World Bank. n.d.b. “Labor Force.” http://tinyurl.com/njndrv47.

World Bank. n.d.c. “Population Estimates and Projections.” http://tinyurl.com/5n8wtcpw.

Yasin, Ibrahim. 2023. “The Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon: Between Political Incitement and International Law,” Arab Center Washington D.C., October 3. http://tinyurl.com/2vd4jt6f.

Yesha Council. 2022. “Population Data Report for Judea & Samaria and the Jordan Valley – as of January 2022,” March 6 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/muvx67ts.

Zimmerman, Bennet, Roberta Seid, and Michael A. Wise. 2006. “The Million Person Gap: The Arab Population in the West Bank and Gaza.” Begin-Sadat Center, Bar-Ilan University (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/5cxxzu7w.

Zubida, Haim. 2023. Help Israeli Businesses and Let Palestinians Work Here. Ynet, August 28 (in Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/yxsuej7c.

______________________-

[1] The replacement-level fertility rate is the fertility rate that is sufficient for one daughter to replace one mother. In industrialized countries, where the age-specific mortality rate is low, this rate is 2.1 children per woman.

[2] The demographic momentum is the effect of the current age structure of the population on its future growth rate.

[3] In 2021, of the entire EU population, 21% were above the age of 65 while the median age was 41.1. This age is expected to rise to 50 in the next generation (Eurostat 2023).

[4] As a generalization, it can be said that until the Rabat Conference (October 1974), the Palestinians were opposed to any option of dividing the territory “west of the Jordan River” into two separate political entities, while after the June 1967 War Israel was, and still is, opposed to such a solution.

[5] See, for example, the stormy debate in the Knesset on December 30, 2003 on the subject of “The loss of Jewish majority between the Jordan River and the sea.” On October 25, 2004, during the debate on the disengagement from the Gaza Strip, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon said: “We don’t want to rule forever over millions of Palestinians whose number doubles every generation. Israel, aspiring to be a model democracy, cannot sustain such a situation for long.” https://katzr.net/1e677d. See also Even, 2021.

[6] Demographic policy refers to the governmental policy in three areas: natalist policy; population dispersion within the country itself and in territories under its control, namely the settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (until the disengagement in 2005) in the Israeli case; and the immigration policy, which, in the Israeli case, includes the Law of Return (1950) and its amendment (1970), and the Citizenship Law (1952).

[7] Overall, during the years 1974–1989, the number of Israeli Jews rose by 27.9%, while the number of Israeli Arabs increased by as much as 63.7% (CBS, 2021a, Table 2.1).

[8] Prior to Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem and the granting of permanent residency status to its non-Jewish residents. A permanent resident can live in the country and enjoy all the rights of an Israeli citizen, except for the right to vote for the Knesset (the Israeli Parliament). Although permanent residents are not citizens, they are included in the population count of Israel. In mid-2022, 355,000 Arabs residing in East/Arab Jerusalem had permanent resident status.

[9] The attempts by industrialized countries to adopt policies that encourage higher fertility show that high child allowances and other economic benefits for families with multiple children encourage or maintain high fertility only among families of low socioeconomic status (Winckler 2008).

[10] During 1990–2001, the total number of immigrants to Israel amounted to 1.09 million (CBS 2016, Figure 1).

[11] The fertility rate of Israeli Muslims fell from a peak of 9.87 children per woman in 1965 to 2.91 in 2022 (CBS 2023b).

[12] During 2001–2003 Israel’s per capita GDP fell by 6.1%—more than in any other period in Israeli history, including 2020, during the Coronavirus pandemic (CBS 2022a, Table 11.2).

[13] On the sharp decline of the fertility rate among the Bedouin of the Negev, see Abusrihan and Anson 2021.

[14] Out of 179,500 Christian citizens of Israel at the end of 2020, 76.7% were Arabs and nearly all the rest were Christians who immigrated to Israel due to the amendment to the Law of Return (CBS 2021b).

[15] Income in kind (or in-kind income, benefit in kind) is income that is not cash but equivalent to cash, for example, a discount on municipal taxes, reduced electricity and water tariffs, cheaper public transport, or tax credits for young children.

[16] The fertility rate of ultra-Orthodox Israeli women fell from a peak of 7.36 on average in the years 2003–2005 to an average of 6.56 in the years 2017–2019 (CBS 2020, Table 3; CBS 2023c).

[17] The overall fertility rate of non-religious Israeli-Jewish women rose slightly, from 1.93 on average in the years 2003–2005 to 2.08 on average in the years 2017–2019. The main factor in this rise was the increased fertility rate among the second generation of immigrants from the former Soviet Union and those who came at a young age and were educated in Israel, compared to their mothers. Most of these women married native Israelis and adopted the fertility patterns of non-religious Israeli-Jewish women (CBS 2020, Table 7; see also Winckler 2022).

[18] In March 2024, the Bank of Israel interest rate was 4.50% and the prime rate stood at 6.00%, after ten consecutive rate increases since April 2022. This steep increase in the interest rate meant an average rise of more than ILS1,000 in monthly mortgage payments (Green 2023).

[19] For details of the Law of Return and the 1970 amendment, which allowed the “third generation” to immigrate to Israel, see Gavison 2009.

[20] The Director General of the Population and Immigration Authority.

[21] Yulia Malinovsky and Elina Bardach-Yalov.

[22] It should be noted that the findings of this study have been refuted by many, notably by Sofer and Gambush (2007) and Della Pergola (2007).

[23] In the religious composition of Israel’s population, the “Others” appear in a separate category (2023d, Table 2.2), while in the presentation by “population group” (2023d, Table 2.3), the categories are “Jews and Others” and “Arabs.” See also Sasson, 2022.

[24] In previous elections, about two-thirds of the immigrants from the former USSR voted for immigrant parties (primarily Yisrael be’Aliyah followed by Yisrael Beitenu). The remaining third mostly voted for right-wing parties (Likud, Kulanu, and Tikva Hadasha), with only a few voting for left-wing parties (Konstantinov 2022).

[25] As of September 2023, out of 8.5 million Jews living outside Israel, more than 7.7 million were living in OECD countries (The Jewish Agency 2023).

[26] In 2022, the fertility rate of the Jewish population in the West Bank (excluding East Jerusalem) was 4.59—about 50% higher than the average among the Israeli-Jewish population (CBS 2023d, Table 2.42).

[27] Excise is a fixed-rate tax applied to each unit of a product, such as benzene and diesel fuel in the case of Israel.

[28] The second option for water supplies to the PA is from Jordan. However, due to the severe water shortage in Jordan, this option is not realistic, as Jordan itself relies on water supply from Israel.

[29] This figure was provided by Itai Kovarski from the Water Authority in the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee of the Knesset on May 30, 2022, https://katzr.net/87a95c

[30] According to PCBS, in mid-2021 there were slightly more than 2.6 million people living in the PA territory, excluding East Jerusalem (PCBS 2022).

[31] In 2022 the median age of Jews and Others was 32.3 years, while that of the Arabs was 24.8 years (CBS 2023d, Table 2.5).

[32] The economic activity rate is the proportion of employed people to the total number of the population of the working age.

[33] The term “Asian Tigers” refers to four countries—Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan—which, within a few decades (1960s–1980s), transformed from developing economies into industrialized ones.

[34] In 2020, the Israeli population under the age of 20 numbered 3.31 million, compared to 2.34 million in 2000—a nominal growth of 41.1% over only two decades (CBS 2001, Table 2.10; CBS 2021a, Table 2.3).

[35] The data refers to the second quarter of 2023.

[36] The term “poverty rate” refers to the proportion of individuals or households living below the poverty line.

[37] The higher a country ranks on the index, the greater the threat to its stability.

[38] Estimates of the number of Syrian refugees are roughly seven million, while another seven million are internally displaced (UNHCR 2023).