Strategic Assessment

The article presents a new theory for analyzing ethno-nationalist settlement from a perspective that has not yet been studied, which I term a “demographic campaign.” This refers to a phenomenon of geopolitical strategic settlement that is evidenced by historical case studies. These cases form the basis for a model, which will then be applied to Palestinian settlement in Firing Zone 918, which is situated in Area C in the South Hebron Hills. To establish the theory, I will employ the complex systems model alongside settlement models used by many Israel studies researchers. This theory helps understand how non-violent ethnic and nationalist struggles to shape future borders are waged, and how frontier settlement occurs in disputed areas, along with analyzing the Palestinian Authority’s struggle to shape its future borders by settling Area C. The concept of the demographic campaign could create an opening for future researchers to analyze settlement enterprises from a geographical and demographic perspective, but also and primarily, from a systemic and strategic perspective.

Keywords: Campaign, demography, demographic campaign, Palestinian Authority, IDF, Area C, firing zone, illegal construction

Introduction

The set of strategic threats that Israel is facing include demographic challenges and the geographical expansion of the Palestinians and Bedouins in the Jordan Valley, South Hebron Hills, and northern Negev regions. It seems that these complex challenges are not adequately addressed by the country’s leaders, who are preoccupied, to some extent justifiably, with military, political, economic, and social challenges that pose more imminent and tangible threats at this time.

In June 1967, Israel captured the West Bank, but refrained from annexing it and maintained the status of the region as a conquered territory under military administration. In the framework of the Oslo Accords (Oslo II, which determined the administration of the West Bank, was signed in Washington on September 28, 1995), the West Bank was divided into three types of territories: Area A, in which security and civilian responsibility was transferred to the Palestinians; Area B, in which only civilian control was transferred to the Palestinian Authority; and Area C, in which security and civilian control remained in the hands of Israel. Area C included blocs of Israeli settlement and areas of strategic and military importance, including the Jordan Valley and the desert frontier region.

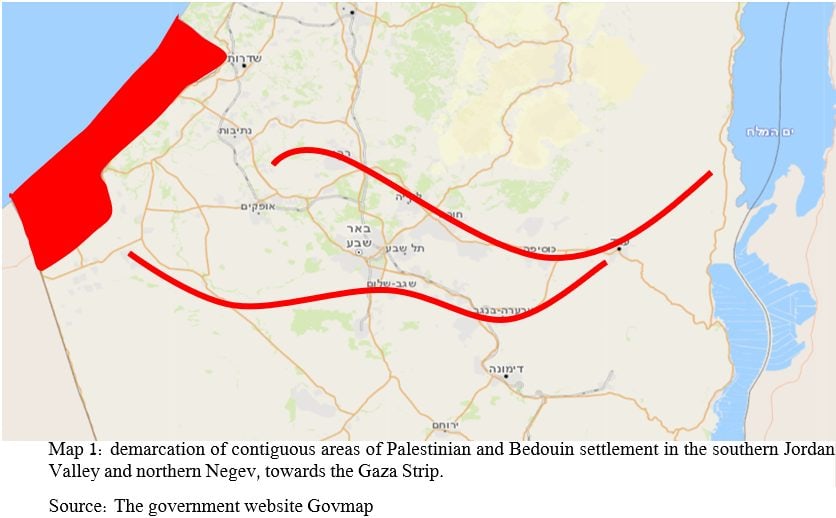

During the 30 years that have passed since the signing of the Oslo Accords, the map of settlement in the West Bank has changed beyond recognition. Bedouin and Palestinian expansion have created an almost continuous “settlement belt” between the Gaza Strip and the Jordan River, via the South Hebron Hills and the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the northern Negev (Bystrov and Soffer 2010).

This development could drive an ethnic wedge between southern and central Israel, which could deteriorate into a military wedge; that is, the failed attempt to detach the Negev from the Jewish state in 1948, could be achieved in the future through demography. Firing Zone 918 in the South Hebron Hills is one of the last links needed to complete a “chain of ethnic detachment.”

This article focuses on three issues. The first is a proposed theoretical model for describing the phenomenon that we will call a demographic campaign. This is explained and then demonstrated deductively through historical case studies. The second issue focuses on examining Palestinian settlement in Firing Zone 918 via the model of the demographic campaign and explaining why this settlement is revolutionary and not evolutionary. The third issue analyzes the unique characteristics of the Palestinian demographic campaign as a whole, via inductive analysis of the settlement in Firing Zone 918.

Conceptual framework

The theory of the demographic campaign is based mainly on three concepts: campaign, demography, and a third concept that is a hybridization of the first two, which is one of the innovations and contributions of this study—the demographic campaign. The study also relies on geographical models that sketch out the development of settlement in the area, as well as the theory of complex systems.

Campaign

A campaign contains several characteristics that distinguish it from the strategic level above it and from the tactical level below it. We can identify five main elements that appear in most campaigns: First, the element of conflict or competition; second, the campaign level aims to mediate between abstract strategy and mechanical tactics, which requires integrativeness (Saint 1990); third, the campaign is composed of several interrelated components that create something holistic together; fourth, despite its holistic nature, it forms only one component of something bigger than it (Naveh 2001), for example a campaign as a component of a war on one front, or a diplomatic, economic, or cognitive campaign. The role of the campaign is defined by the strategic level through defining a strategic objective and national political objectives (FM 100-5 Operations 1993). The fifth component: the campaign is defined as an art because it demands great creativity and non-linear thinking, as part of recognizing the factor of randomness and the chaotic dimension that stems from the encounter with adversarial systems (Franz 1983). The theory of complex systems (Razi and Yehezkeally 2006) provides explanations about the development of seemingly anomalous phenomena that are byproducts of complex systems, due to the absence of linear development. With the help of this theory we can explain certain elements of the campaign, which is also a complex system.

Demography

Demography involves the study of population, including its distribution and the changes that occur in it over time, as well as the analysis of different populations in territorial contexts. Politics is known to have great influence on demographic changes in several ways. First, politics influences the production of demographic information and biases it in its favor—for example the dispute surrounding the number of Palestinians living between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea (Zimmerman et al. 2006). Another substantive influence is expressed in natalist policy (Barrett 1995), whose purpose is to encourage or to suppress childbirth—for example Chinese childbirth policy (Friedman 2010). Another substantive aspect, which the study also focuses on, is expressed in a policy that encourages migration.

Demographic campaign

The term demographic campaign is an oxymoron. On the one hand, a campaign is the product of comprehensive planning and mainly deals with the relations between man and man, for example rivalry between groups (Naveh 2001). On the other hand, demography follows unplanned natural patterns and deals with the relations between man and place (geography)—childbirth with respect to territory (Khamaisi 2011). However, in this paradox lies the importance of the concept, which seeks to describe a phenomenon that seems to be influenced by the laws of nature, but national interests channel it towards their needs.

The process of shaping countries and borders in the service of nations and rulers has taken various shapes throughout history. For example, a strategy of “divide and conquer,” which originated in ancient times, or population transfers such as the Indian-Pakistani population transfer. But the term demographic campaign aims to describe a completely different settlement strategy.

The Palestinians have often addressed the demographic aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Many believed and still believe that its resolution will be determined by demography. Consequently, granting the right of return to the 1948 refugees is a basic Palestinian demand in all negotiations, not only out of considerations of justice and conscience but also as a means of countering Zionism and cancelling the achievements of the demographic revolution that it brought about through the waves of Jewish immigration (Zilbershats and Goren-Amitai 2010).

The Palestinian leadership recognized the need to formulate a “demographic policy” as a counterweight to the Israeli policy, which it called “settler colonialism.” The PLO leadership maintained that demography would support the advancement of Palestinian interests and serve as a bargaining chip. Yasser Arafat was quoted as saying “we know the importance of the demographic factor as one of our weapons,” and even called the Palestinian woman “a biological bomb threatening to blow up Israel” (Steinberg 1995).

But the collapse of the Soviet Union and the arrival in Israel of about a million new immigrants in the 1990s, were seen by the PLO as a fatal blow to the Palestinian demographic effort, which was set back a generation in one fell swoop (Galili and Bronfman 2013). At this point of crisis, land became of crucial importance for the Palestinians, who changed their focus from a passive demographic effort based on childbirth to an active demographic effort that included taking over land. The element of land in the Palestinian campaign, which is called “steadfastness and clinging to the land,” is an important part of the Palestinian struggle to shape their future state.

We can deduce that we are facing a national effort to shape the borders of a state in the making. This effort is not new, is not a Palestinian invention, and so far has not been seen as a campaign or as a classic demographic policy. This is the place to try to define it as a demographic campaign.

A demographic campaign is a geopolitical effort that seeks to shape future borders and to shape the territory by driving a population wedge within contiguous sovereign territory and disrupting the exercise of this sovereignty in areas of territorial dispute between different national groups through a strategy of settlement that aims to take over territories without the use of armed force, sovereign legislation, or political agreements. Consequently, the demographic campaign is waged in a cunning, creative, secret, and undeclared manner,[1] while taking the initiative in the conflict, including taking unilateral action on the ground.

This definition will be tested below, but first it is important to understand the development of Arab settlement in the Land of Israel as a basis for analyzing the case study of Firing Zone 918.

The Development of Palestinian Settlement

Studying the characteristics of traditional Palestinian settlement in the Land of Israel and examining the geographical and demographic prism will help with understanding the settlement in Firing Zone 918. Is it a geographical expression of natural growth or an unconventional development that is difficult to explain using existing geographical models, but can be explained using the demographic campaign theory?

Demography has had a great impact on the development of the Arab village. The expanding clans led to crowding and physical expansion. Starting in the middle of the nineteenth century, there was a constant trend of growth among the Arab population in the Land of Israel, which stemmed in part from immigration (Marom 2008, 102-103), including among the Hauranis, the Circassians, and the Mughrabis.

Certain regulations also hastened the growth and development of the villages. For example, an Ottoman law that required the establishment of a mosque in each village created an economic burden and increased the desirability of merging clan complexes into a single village. Some of the current names of villages bear witness to these mergers. For example, the village of Tarqumiyah evolved from “Tricomia,” which means three villages, while the village Al Fandaqumiyah developed from “Pentakomia,” which means five villages (Grossman 1994). Security considerations also promoted population density and the concentration of settlement (Bar-Gal and Soffer 1976).

As the population grew, the need arose to create new living spaces and additional sources of livelihood and food, hence the need also arose to cultivate areas distant from the village (Ben-Artzi 1988). This need brought about the development of “villagettes”—small villages that were “daughter villages.”

The daughter villages had many names such as khirba (Arabic for ruined or abandoned place) as they were established on the ruins of ancient settlements; the farms were called “mizraot” (מזרעות) from the root z-r-ayin meaning seed; and “izbot” (עִזבּוֹת) from the root meaning leave or evacuate, because they were abandoned for periods of time during the year. As long as there were no conflicts over land, the “izbot” remained seasonal. Over time, the “mother villages” spread until they swallowed up parts of the daughter villages, while more distant daughter villages developed as independent villages. This signaled a significant change in the settlement layout (Biger and Grossman 1992).

Another kind of temporary settlement that was characteristic of the Judea region is called marah (Arabic for “to rest”). The marah was used by shepherds as a rest stop and also included sheep pens and proximity to water sources. In the desert frontier region, due to the dry climate, the marahs usually comprised caves and tents. In Samaria this type of settlement was called nazla from the root n-z-l, which hints at a descent from the hills to the lowlands. In the Sharon region, the pastures of nearby villages were called ע'אבות (Marom 2008). It seems that the large number of terms stemmed not only from differences between dialects but also from substantive differences in their purpose.

Throughout history, physical and climatic difficulties kept the South Hebron Hills as an area sparsely populated by cave dwellers, alongside very limited above-ground construction. The towns of Yatta, As Samu’, and Ad-Dhahiriya, which delineated the boundary of settlement in the South Hebron Hills, were also cave settlements with a few huts until about 70 years ago. Even in the modern era, the phenomenon of cave-dwellers continued to flourish alongside the marahs, and until the end of the 1990s, there was almost no permanent above-ground construction in the desert frontier region. Research from about 40 years ago estimated the amount of settlement in the Hebron district caves as around 120 families—a figure that was characterized by constant regression (Havakook 1985).

Arab seasonal settlement, which can be compared to a work trip, did not require the development of infrastructure such as electricity, water, schools, and mosques. Furthermore, the shepherds used to leave their families behind at the mother villages, and only those who were needed for shepherding moved to the caves (Havakook 1985).

During the past three decades, many deviations from the traditional settlement model can be identified in the expansion of Palestinian settlement in the South Hebron Hills, including expansion towards arid areas; a transition to irrigated agriculture; increasing political involvement in the region and more. All of these and more make one wonder whether the “invisible hand” has been replaced by one that is pulling the strings.

Déjà vu?

Before examining Palestinian settlement in Firing Zone 918 by means of the demographic campaign theory, this theory is demonstrated deductively using two case studies—Tower and Stockade and the Alon Plan—, which have a broad common denominator with Palestinian settlement in the topic of the study, based on five dominant components: the actors —Israelis and Palestinians; the location —the Land of Israel; the goal —taking over territories as part of shaping future state borders; the method —settlement; characteristics and principles —based on Clausewitz’s famous expression that the demographic campaign is the continuation of war by other means.

All three cases refer to an organized strategy, even if it is not officially declared. All three cases involve a zero-sum game between Israel and the Palestinians. In all three cases, the sides took extra care while hiding their true intentions, in order not to provoke the anger of their adversaries and other international actors. In all three cases new areas of settlement were chosen in order to increase living spaces, and all three involve an ethnic nationalist struggle.

The similarities mentioned make Tower and Stockade and the Alon Plan suitable case studies for the issue at hand. These campaigns, which ended long ago, could indicate the future strategic consequences of Palestinian settlement in Area C.

Tower and Stockade 1936-1939

The Tower and Stockade period is an important chapter in the history of the protracted campaign over the Land of Israel that has taken place between the Jews and the Arabs, which has been characterized by many “settlement conquests.” The Tower and Stockade plan had several strategic objectives. First, strengthening the “N of settlement”[2] in the sense of strengthening a settlement and expanding it in order to broaden the chain of settlements and strengthen the Jewish presence in the connecting corridors (Orren 1987); second, conquering new living spaces that would enable absorption of future Jewish immigration and the exercise of property rights in the lands under Jewish ownership; and third, shaping the borders of the state-in-the-making by taking over new areas while the Peel Commission (1936) was operating in the background and considering the partition of the country, and there was a need to hurry and create demographic facts on the ground.

Judging by the results, there is no doubt that this strategy faithfully served the Zionist enterprise, bringing about a three-year settlement boom against all the odds, in which the weaker side on paper initiated a campaign and expanded Jewish settlement in an unprecedented manner. Along with the settlement operation in 1946 in which 11 new settlements were established in the Negev in response to the Morrison–Grady Plan, it can be said that Tower and Stockade contributed more than any other military effort to the conquest of the Land of Israel. The official proof of the success of this strategy came on November 29, 1947, when the UN adopted the partition plan according to which most of the areas of the “settlement conquest” were included within the territory of the Jewish state.

Thus, Tower and Stockade constitutes a historic example of waging a successful settlement strategy that led to bigger achievements than the Jewish community could have achieved using the military means at its disposal at that time, and the series of local settlement actions shaped international decisions on borders despite its military and political inferiority.

The Alon Plan

Yigal Alon frequently discussed the idea of conquest through settlement (Alon 1968). After the Six Day War, Alon served as chairman of the ministerial committees on Jerusalem and Hebron and as chairman of the settlement committee, and thus was very involved in settlement. After the end of the war, Alon devised a plan for shaping new borders for the State of Israel known as the Alon Plan. The plan was never officially adopted by Israel’s governments but was implemented by them, at least partially, by settling the Jordan Valley (Arieli 2013).

In Alon’s assessment, retaining the conquered territories in their entirety would lead to continued hostilities between Israel and the Arabs. On the other hand, he was concerned that a withdrawal to the 1949 lines would also encourage continued Arab aggression (indeed, withdrawals for the purpose of conciliation were more than once interpreted as weakness, for example the IDF’s withdrawal from the security zone in Lebanon). Alon concluded that it was necessary to forge a middle path and shape optimal borders to fortify Israel’s security and its future (Gelber 2018).

Alon wove the essence of his conception into his political and settlement plan, which was based on two main principles: secure borders and a minimal Palestinian population within them. These principles aimed to maintain Israel as a Jewish and democratic state thanks to a Jewish majority, while refraining from harming the rights of the Arab minority (Gilead 1980).

The essence of the plan that related to the West Bank included five main principles (Alon 1980): the Jordan River as Israel’s eastern border; creating strategic depth by annexing a 10-25 kilometer wide strip and opening corridors to Jerusalem, including minimal annexation of Palestinians; annexing parts of the Hebron Hills and the Judean desert; establishing outposts in the territories that were to be annexed; and enlisting the international community, including Arab countries and the Palestinians, in the proposed solution, meaning pushing for peace negotiations while carrying out unilateral Israeli actions, out of a belief that the potential opponents would feel that time and recalcitrance were working against them.

Yigal Alon noticed that the natural drainage divide in the Judean Mountains and Samaria is a kind of settlement divide for the Palestinians: 90% of the population of the West Bank lived west of the line, towards the lowlands and the coastal plain, areas with considerable precipitation. East of the line the population was sparse. Consequently, in a cost-benefit calculation, annexation of the Jordan Valley would add much territory to the state and serve as an eastern security strip while the demographic consequences of annexing it seemed marginal, amounting to the annexation of about 15,000 Palestinians (Cohen 1973).

Alon believed that only the work of the plow would shape the borders of the country and indeed, within a decade, 16 new settlements were established just within the area of the Jordan Valley, and by the time of Alon’s death in 1980, six more settlements had been established. Today there are 28 Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley (in the part conquered in 1967). In addition, the Alon Road was cleared, physically and conceptually delineating the plan’s boundaries in the Jordan Valley region.[3]

15 out of the 28 settlements began as Nahal settlements, meaning that the army, as emissary and agent of the political leadership, was active in implementing the plan. Later the kibbutz movements, Beitar, and other civilian bodies helped civilianize the settlements. Many government ministries, including the Ministries of Energy, Construction and Housing, Transport, and others helped implement the plan with the investment of billions of shekels that included paving hundreds of kilometers of roads and laying infrastructure.

The elements of the demographic campaign are evident in the Alon Plan and in the way it was implemented: in the background was the conflict over land between Israel and the Arabs and its main purpose was to reshape Israel’s borders. While Israel conquered the territories, Yigal Alon maintained that conquest is a temporary situation and permanent borders should not be shaped by the force of arms. Yet prior to international intervention and entering peace negotiations, Alon aspired to shape the borders through legislation and annexation—an ambition that went unfulfilled. Consequently, the basis of defining the demographic campaign as “not by force of arms, not by virtue of legislation, and not by virtue of international agreements” applies. Instead, Alon aspired to shape the borders through a settlement strategy that was expressed in the establishment of settlements that aimed to create facts on the ground. It can be claimed that the plan, at least partially, was successfully implemented without causing much of an uproar and without intensifying the internal debate surrounding construction in the territories. The reason probably lies in the fact that the plan did not receive official Israeli approval, thus it was “covert and undeclared” according to the definition of the demographic campaign. The elements of creativity, cunning, and initiative in the definition of the demographic campaign are inherent in the method of military settlements that were later civilianized. This process streamlined the physical development of settlements and the public psychological process of getting used to the idea of settlement in this area of land, while weakening political and diplomatic opposition, as it was outsourced to the IDF, which was at the heart of the Israeli consensus then as now (Gelber 2018).

New Palestinian Settlement in Firing Zone 918

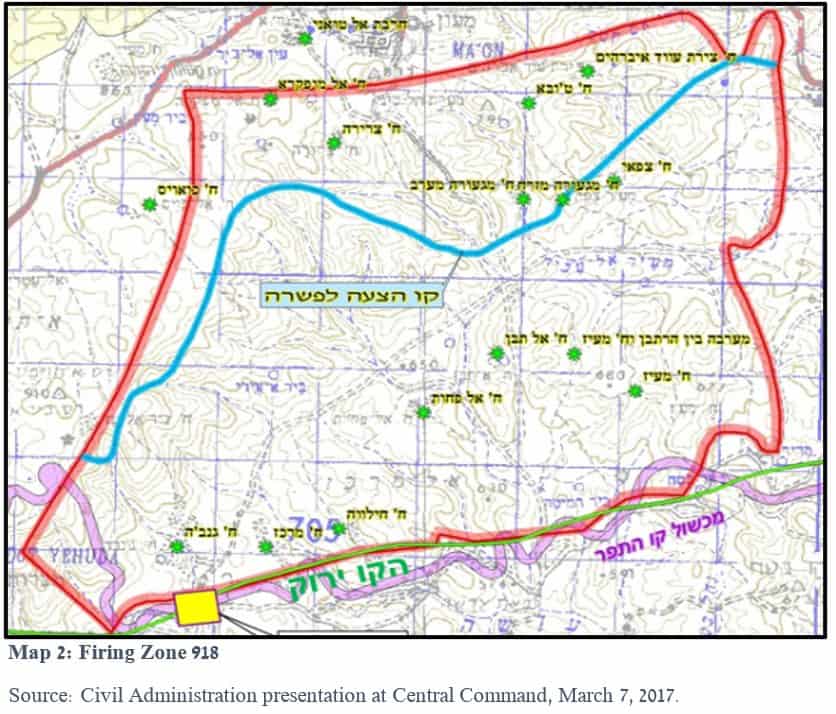

The IDF uses Firing Zone 918 for training, and it has been defined by law as a closed military area since 1980. This means that any entry and activity inside it requires the army’s approval (Order Regarding Security Instructions, 2009). However, today there are 14 points of Palestinian settlement inside the area.

It is a 25-square-kilometer polygon that stretches from the southeastern slopes of the Hebron Hills to the Arad Valley and the Negev. It has a desert climate, and the average annual precipitation is below 200 mm (Israel Meteorological Service n.d.). The Palestinians call the area Masafer Yatta.

Even after the signing of the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1995, Israel made sure to maintain its control of Firing Zone 918 as Area C. But the towns of Yatta, As Samu’, and Ad-Dhahiriya became Area A under full Palestinian control, and as a result, the Palestinian Authority unofficially and covertly became a dominant governmental body in the region, in violation of the agreements with Israel. This claim is supported by a solid evidentiary basis that is partly backed by Palestinian sources, and the IDF is also aware of the problem. Below are several examples collected during field research in Firing Zone 918 and in IDF archives.

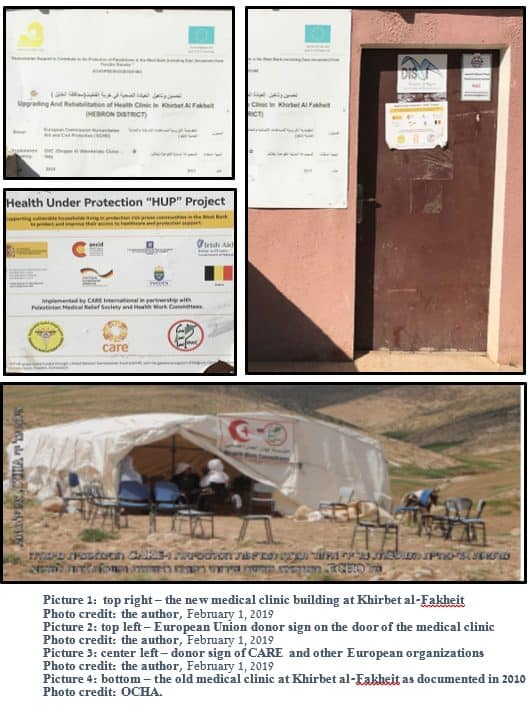

At Khirbet al-Fakheit, which is in the center of the area, no above-ground structures were seen until the middle of the 1990s. The first above-ground structure was identified in a photographic survey in 1999, while 39 structures were revealed in a photographic survey in 2018. This is a steep rise in the amount of illegal construction.

The number of Palestinians staying at the khirba during a tour conducted as part of the study totaled 15—a negligible number compared to the number of structures there, and given that there is a school located there. The Palestinians staying at the khirba were residents of Yatta, according to their testimony and their documents (see below, personal interview, February 1, 2019). According to them, the khirba is only a source of livelihood for them.

The water cisterns have been replaced by water towers, which are connected to plumbing and to systems for filtering and pressurizing water. A large number of solar systems provide electricity to the buildings, to a tent and to a livestock pen. Satellite dishes are also widely distributed at the khirba. Dirt roads to the khirba have been cleared and leveled, their quality and maintenance allowing every kind of vehicle to drive on them, and drainage pipes have been laid underneath them, allowing water to flow through ravine channels in the winter without blocking roads.

In a 2013 report by OCHA (the UN Office for Coordinating Humanitarian Affairs in the region) there is a picture of a white tent. The writing underneath it states that it is the medical clinic of Khirbet al-Fakheit, and on its side it states that the picture was taken by the organization in April 2010 (OCHA 2013). But in 2015 a stone building used as a medical clinic was established in the khirba through foreign donations. The school and the medical clinic seem abandoned, without basic equipment such as books or medical supplies, which would indicate their proper functioning. Olives are grown at the khirba—new agriculture that didn’t exist in the region in the past, as attested by aerial photos.

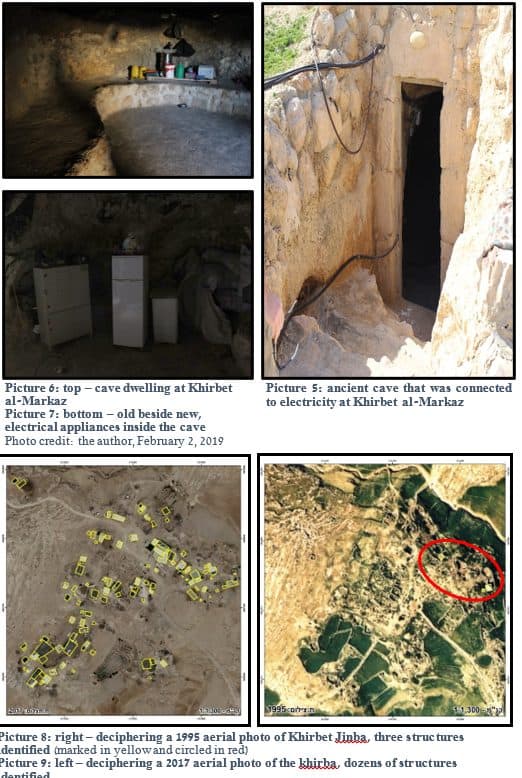

At Khirbet al-Markaz one notices ancient caves that have been converted into seasonal dwellings and many archeological findings that are scattered in the area. A number of caves are still used as

dwellings and enclosures for flocks. In recent years these have been connected to electricity produced using solar panels that look like modern foreign import among the antiquities.

As of February 2019, a single six-member family lived at the khirba—parents in their 30s and their children, as attested by the father of the family (see below, personal interview, February 2, 2019). According to the father, his family is poor and raises livestock and produces various products from it. This is in total contrast with the amount of new construction at the khirba and the amount of infrastructure laid there in recent years. In a photographic survey conducted in 1999, no above-ground structures were identified in the area, but a photographic survey in 2019 revealed 42 structures in the area.

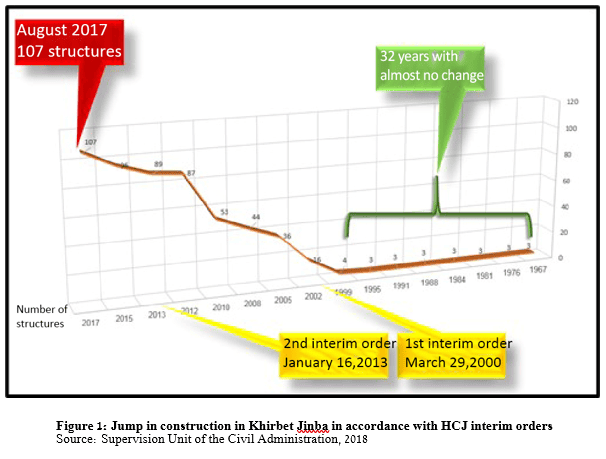

Khirbet Jinba is the largest settlement in Firing Zone 918. A comparison of the aerial photos taken over the years shows that more than 100 structures have been built at the khirba in less than 20 years, which can house hundreds of people and thousands of sheep and goats. The structures and the infrastructure at the khirba have similar characteristics to those identified at the two khirbas surveyed above. Only about 15 Palestinians were found there during the study, and they too were registered as and stated that they were residents of Yatta.

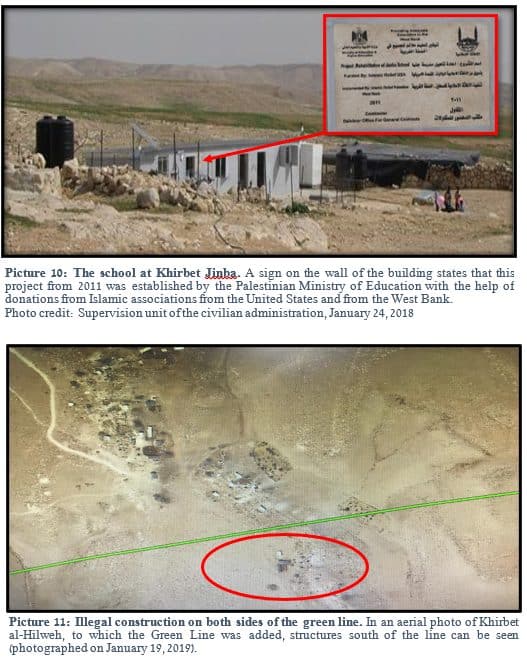

Agricultural lands near the khirba are cultivated and irrigated, leading to large-scale consumption of two basic resources: land and water. In 2011, a school was established at Jinba too, with the help of the Palestinian Authority and other organizations, as attested by the sign hung on the front of the building (see Picture 10).

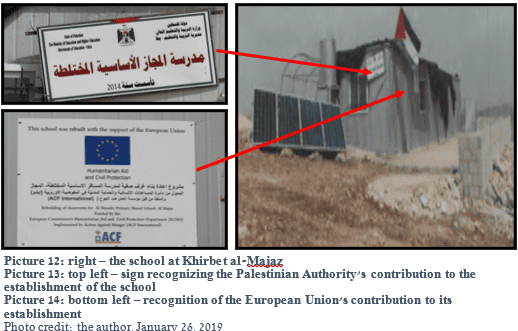

Khirbet al-Hilweh touches the Green Line, and there too the same developmental characteristics as at the other khirbas mentioned can be found. But at this khirba, the settlement development has already crossed south of the Green Line. According to the Palestinians present there, the European Union funded the construction and the infrastructure in return for them being willing to live there. European Union stickers on the windows of the buildings and other infrastructure in the area also indicate the funding sources. In a photographic survey conducted in 1999, no above-ground structures were seen at Hilweh, while a photographic survey in 2018 revealed 46 structures and many trees planted at the khirba.

Khirbet a-Taban – when passing nearby the khirba, the arid desert landscape is replaced by flourishing green, symbolizing an abundance of water. Dozens of dunams of olive trees have been planted near the khirba in recent years. This is a new phenomenon in the desert frontier region, as we can learn from history and from IDF aerial photos from 1999-2018. Crops were seen in many of the khirbas in the firing zone.

At Khirbet al-Majaz we again encounter the involvement of the Palestinian Authority and the European Union in funding projects, such as the school built in 2014.

Maintenance of roadways—On January 31, 2019, as part of the Civil Administration’s enforcement operations, roadways illegally cleared in Firing Zone 918 were blocked. The following day, as part of a field tour that was carried out, it was found that all of the blockades had been broken through. The achievements of IDF activity that had been planned for several weeks and in which considerable resources had been enlisted, were erased within a day. The fact that the activity was kept secret and its implementation required the use of heavy engineering equipment, indicates a quick and effective response by those who broke through the blockades, in an attempt to enable daily life in the firing zone.

Law and enforcement

During the past 25 years, Firing Zone 918 has become a focal point of legal wrangling at the High Court of Justice (HCJ) between the Palestinians and the IDF. As stated above, this area was declared a firing zone in 1980 and was chosen for this purpose given the fact that there were no permanent settlements there. This is supported by the archive of the Civil Administration’s supervision unit and was presented to the HCJ by representatives of the administration and in the affidavit by Professor Moshe Sharon, who, in his role as advisor for Arab affairs in the Office of the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, conducted comprehensive tours of the area before the declaration (HCJ 413/13 and 1039/13, 2018.

In 1985, the Civil Administration and the region’s mukhtars (Arab village chiefs) came to an understanding that twice a year for one month, an entry permit to the area would be provided for the purpose of pasturing, on the condition of a prohibition against staying in the area overnight. This procedure was generally respected, until in 1994 the Palestinians decided to withdraw from the understanding. From 1983 to 2000, dozens of enforcement actions were taken in the area against trespassing, which included evicting encampments, seizing trespassing vehicles, and expelling or seizing flocks (HCJ 413/13 and 1039/13, 2018).

In 1997 the Palestinians submitted three petitions to the HCJ against the eviction: 6754/97, 6798/97 and 2356/97. The HCJ rejected the petitions and instructed the sides to readopt the 1985 pasturing and cultivation agreement. In light of the HCJ’s decision, forced eviction of the area began in 1999, and by the end of February 2000, the eviction of several khirbas was achieved and the area was cleared of construction and infrastructure violations.

In March 2000, the Palestinians again petitioned the HCJ (517/00). Unlike the previous time, the HCJ issued an interim order to freeze the situation until the petition could be clarified. Consequently, the Civil Administration was forced to freeze enforcement actions including eviction and demolition, while the Palestinians were required to refrain from entering without coordination, and, a fortiori, to refrain from construction in the area. After the publication of the order, dozens of families invaded the firing zone. The supervision unit began an eviction proceeding that was blocked due to another petition to the HCJ (1199/00), which led to another interim order in the spirit of the previous order. In the years afterwards, the Palestinians erected hundreds of structures with the help of the Palestinian Authority and international bodies, while exploiting the interim orders to protect them from enforcement.

From 2004 to 2006 the supervision unit tried to conduct limited enforcement to demolish illegal construction, but these attempts were thwarted via the submission of additional petitions (HCJ 805/05 and 5183/05). In 2002, by recommendation of the HCJ and with the agreement of the sides, a mediation process began, during which several compromise proposals were raised, all of which were rejected by the Palestinians. In retrospect, their opposition to compromise turned out to be right from their perspective, as in the following years hundreds of structures and other infrastructure were built, as described.

In 2012 the HCJ decided to dismiss the petitions and to give the petitioners a three-month extension to submit a new petition. And indeed, in January 2013, the Palestinians submitted two new petitions (413/13 and 1039/13) following which the HCJ issued a new interim order, and construction in the region continued.

In light of the HCJ’s proposal and with the sides’ agreement, another mediation process took place in 2014-2015, headed by retired justice Yitzhak Zamir. In the meantime, the construction in the area continued, and numerous public structures were erected. According to the signs on them, at least some of them were erected during the years 2014-2015, during the mediation process which prohibited this.

In 2016 the mediation reached an impasse, and the supervision unit started to demolish illegal structures in the firing zone. In response, the Palestinians petitioned the HCJ (857/16) requesting an interim order to stop the demolitions. Such an order was indeed issued, and the Palestinians continued to set up infrastructure and numerous structures. This legal saga, only samples of which have been presented, still continues today. Aside from illegal entry into an IDF firing zone, there is another criminal offense, which is damaging archeological sites. As early as 1944 during the British Mandate, Khirbet Jinba and Khirbet al-Markaz were legally recognized as archeological sites. This means that these khirbas cannot be used for residence or agriculture. Both the Jordanian Antiquities Law and the order regarding the Antiquities Law (Judea and Samaria) include these prohibitions. The archeological sites in the firing zone are currently suffering serious damage and neglect, while the relevant laws are being trampled.

The Anomalies of Settlement in Firing Zone 918

An analysis of the findings in the area reveals 15 anomalies regarding the characteristics of the new Palestinian settlement, that are difficult to explain using normal geographical and demographic models.

Traditional versus modern—As a rule, attributing the changes that traditional settlement has undergone to modernization is reasonable, but while most of the new structures stand abandoned, the caves are still used as living spaces. Moreover, most of the structures lack basic furniture and sanitary infrastructure, as do the public buildings, such as the schools without books. Has the process of real estate modernization omitted interior design and equipment for the buildings?

Supply and demand—It should have been expected that the level of construction would correspond with the natural increase of the population. These variables usually correlate closely, as new construction aims to serve new populations, and the latter is supposed to fund this construction. In Firing Zone 918, the amount of construction, which grew by thousands of percent during the past 20 years, is dozens of times higher than the rate of natural increase, which is estimated at about 65% during this time period (PCBS 2018).

Low socioeconomic status versus construction boom—The population of Firing Zone 918 is considered poor and barely makes a living from manual labor. This is attested by studies as well as by the region’s residents. This population is of low socioeconomic status even among the Palestinians. Poverty, alongside the wealth of real estate projects, creates a paradox, that can only be explained via significant economic involvement by wealthy external bodies.

Permanent construction for temporary dwelling —One of the reasons that for hundreds of years no permanent settlement developed in the region is that the desert frontier is also a military frontier. In addition, the climatic conditions in the desert only enabled pasturing during limited periods of the year. Consequently, economic investment in real estate in the region was not only unaffordable, but was also not worthwhile.

Water consumption compared to what the region provides—Life in the region was made even less attractive given the low average precipitation during the past 20 years and the northward motion of the desert line, but the amounts of construction and agriculture has actually increased sharply, through the construction of infrastructure for supplying water, mainly from external sources. It is difficult to believe in the ability of peasants and shepherds in Firing Zone 918 to plan, fund, and operate an infrastructure operation on this scale. Moreover, the Water Authority and Mekorot would not supply water to illegal settlements in the firing zone. During the last two years, the Water Authority and the supervision unit conducted raids in Firing Zone 918 and dismantled illegal water infrastructure, which included pipes dozens of kilometers long for supplying stolen water to the region.

Field crops in the desert are not culturally or economically characteristic of the region’s residents, whose main livelihood for generations has been based on sheep and goats. In recent years, not only has there been an increase in field crops, but they are also based mainly on irrigated agriculture, which is not characteristic of desert regions.

A society without seniors—As a rule, there are two situations in which there are no seniors in a settlement. The first is in pioneering settlements such as Nahal settlements. The second is temporary settlement for work purposes, for example the oil cities in the arctic circle. In the communities in Firing Zone 918 there are almost no seniors to be seen. Out of about 100 Palestinians observed in the khirbas surveyed, the age of the oldest person approached 40. Whether pioneering settlement or settlement for work purposes, the two possibilities contradict the Palestinians’ claim to the HCJ that this is permanent settlement that has existed for generations.

The enforcement paradox —“But the more they afflicted them, the more they multiplied and the more they spread abroad”(Exodus 1:12). In Firing Zone 918 the construction spreads in inverse proportion to the authorities’ effort to curb it. It seems that legal involvement is identified as an accelerating factor and not as one that inhibits illegal construction.

Legal costs—The petitions to the HCJ and their management over the course of years, the production of affidavits and the management of mediation proceedings—all of these involve high costs that could be burdensome for the average person, all the more so for a poor desert dwellers.

The urbanization trend has also affected Arab society (Khamaisi 2000). In the South Hebron Hills we can see how Yatta developed from a small village into a large urban area in Firing Zone 918. It seems as if there is an opposite trend here of leaving the city for the desert, but this is just the way it seems, as most of those present in the area actually attest that they are residents of Yatta and have homes in that town. This is a relatively “weak” anomaly and explanations and examples of opposite trends in the world can be provided, but it joins the other strange characteristics of these settlements.

Disproportionate foreign contributions—It is difficult to explain the interest and willingness of the international community to invest considerable sums in Firing Zone 918, unless we understand the motives of this philanthropy as political involvement with the purpose of helping shape the region for the benefit of the Palestinians and against Israel and the occupation. It’s important to note that European governments see Israeli presence as an expression of colonialism, which they bear as their original sin and thus are motivated by anti-colonialist conceptions that overshadow objective consideration. This is a region lacking important historical or holy sites and natural resources. However, in recent years, the firing zone has become a focal point for European philanthropy estimated in the tens of millions, which is considered quite generous compared to the limited population that lives in the region.

Ghost buildings—Most of the buildings built in the area stand empty, as there are more buildings than people, let alone families, living in the region.

The innovation of public buildings— Until about a decade ago, there were no public buildings in the region, given the fact that residence in the area was for short periods of time during the year—which made the investment unnecessary. In addition, such investment was not within the means of the shepherds and peasants, most of whose money was used for basic existential needs (Havakook 1985). Moreover, the Israeli authorities refrained from building in the firing zone, while the local Palestinian municipalities such as Yatta and As Samu’ preferred to invest their money within their areas and not in the desert frontier region.

Deviation from the Green Line—Even if the Palestinians’ claims regarding their links to Firing Zone 918 are accepted, this cannot explain how the European-funded construction has crossed the Green Line, especially in cases where the issue was brought before the HCJ, which prevented enforcement.

Construction in the firing zone—As stated above, the law prohibits unauthorized entry into the firing zone, a fortiori, living and building in it. In the past the law was fully enforced, but today the HCJ often prevents enforcement of this state law in many parts of Area C.

Findings

This study has presented three case studies of settlement enterprises in the Land of Israel that are deeply related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and are maybe even at the core of it. The first two, Tower and Stockade and the Alon Plan, provide a deeper perspective on the phenomenon of the demographic campaign, while the Palestinian settlement in Firing Zone 918 was brought as a current case study, which raises a reasonable suspicion of the waging of a Palestinian demographic campaign in Area C. As part of researching the area, numerous khirbas were examined as well as aerial and satellite photos from the last few decades, in order to carefully “peel back” the physical changes that have occurred in the area in order to make it possible to understand the developmental dynamic over the years. The main conclusions are presented below.

There is Indeed a Demographic Campaign

The case studies surveyed prove and demonstrate the demographic campaign theory. Despite its complexity, the definition succeeds in providing an explanation for these active, non-violent struggles to shape borders.

As stated above, a demographic campaign is a geopolitical effort that aspires to shape future borders in areas of territorial dispute between different national groups via a settlement strategy, which aims to take over territories without the use of armed force, sovereign legislation, or political agreements. Consequently, it is managed in a cunning, creative, secret, and undeclared manner, while taking the initiative in the conflict, including taking unilateral actions on the ground.

All Indications Point to a Palestinian Demographic Campaign

The anomalies that relate to the construction in Firing Zone 918 indicate non-linear settlement development. While some of the anomalies can be explained as settlement “evolution” lacking political involvement, under the proviso of being unlikely, some of them have no plausible explanation other than the demographic campaign theory. The poor economic situation of the firing zone’s “residents,” which would not enable them to develop the region in the way it has developed, the extreme discrepancy between the number of structures and the number of settlers, and the impressive pace of construction, which is dozens of times the rate of natural increase—all of these and more leave no room for doubt that this is a demographic campaign that the Palestinian Authority has been waging against the State of Israel in the region since the middle of the 1990s.

In addition, the lifestyle adopted by the firing zone’s residents is relatively modern and deviates from what is customary among the desert-dwelling shepherds. Another even more extreme deviation can be seen in the supposedly private monetary investments in construction and infrastructure projects that are incompatible with the limited capital at the disposal of the peasants and shepherds in the region.

There is large-scale investment in the establishment of “sensitive” buildings (a term taken from the laws of war; this category includes schools, medical clinics and more, which public opinion has difficulty tolerating harm to). The lack of basic equipment in the school and the clinic poses a big question mark: were these built for the public benefit or were they intended for creating monumental facts on the ground, which would prevent or at least make it difficult for those seeking to remove them? It seems that these public buildings are a win-win situation, as leaving them in place is a territorial achievement, while their demolition would lead to considerable criticism of Israel, serve the Palestinian narrative, and constitute a psychological achievement for them.

The field work at the various locations, along with the documents surveyed, with an emphasis on the aerial photos, affidavits submitted to the HCJ by the two sides, and the research work of Yaakov Havakook compiled in his book (1985) all point to the conclusion that the settlement in Firing Zone 918 is not a process of “natural” development of Palestinian settlement in the region, in breaking every reasonable logical and linear line of development. Consequently, this settlement can be seen as a clear expression of a Palestinian demographic campaign taking place in the region in question, and proof can be found of the existence of all eight elements in the definition of the demographic campaign:

Effort: A series of actions intended for one purpose. The settlement effort in Firing Zone 918 includes a collection of actions from different fields, such as mechanisms of funding, law, advocacy, and of course construction. This effort requires considerable time, manpower and money.

Geopolitics: This is a geographical region in which political wrangling is taking place between Israel and the Palestinians, with the involvement of other countries.

An aspiration to shape future borders in areas of territorial dispute: The Palestinian focus on this arid area that lacks resources stems from the understanding that settling the frontier is a powerful tool in shaping borders (Turner 1893). Their assumption is that the Jewish settlement enterprise in the West Bank is “a little annexation enterprise with about half a million workers” which, if it continues linearly, will lead to a significant increase in the Jewish population and the seizure of additional areas in order to create more significant territorial contiguity.

Between different national groups: the Israeli Jews and the Palestinians.

Via a settlement strategy that aims to take over territories: The settlement enterprise in the firing zone aims to ensure the seizure of the open territory by the Palestinians.

Without the use of armed force, sovereign legislation, or political agreements: The Palestinians do not have the power to take over the land by war, and Israeli legislative channels and political channels are currently closed to them.

Cunning, creative, secret, and undeclared: We will expand on this element below. But the very fact of settlement being an ostensibly basic need that does not pose too much of a tangible threat, is in itself cunning, and does not lead to strong opposition from the other side. Another example of cunning and creativity is the exploitation of the HCJ to paralyze the systemic threat and to continue the construction under its auspices. The question of “why” is an important question that will be left to future studies. This study focuses on the question of whether—whether there is a demographic campaign, whether legal tools are used as part of it, and whether the legal tools were effective.

While taking the initiative in the conflict, including taking unilateral actions on the ground: The Palestinians are initiating the construction, vis-à-vis the sovereign that is trying to thwart it. The sovereign’s response is not expressed in the establishment of Israeli settlements, because it is a firing zone. Consequently, the act of Palestinian settlement is done unilaterally.

Characteristics of the Palestinian Demographic Campaign

As stated above, secrecy has a central role in preserving demographic campaigns. Consequently, there is no declared Palestinian policy regarding construction in Area C, but no fewer than ten main principles and patterns of action can be identified that distinguish the Palestinian demographic campaign.

Planning: The Palestinian Authority invests its time and money in planning the demographic campaign and makes sure to put it in writing, while attempting to avoid its publication. This planning is meticulous and does not omit any detail. The regional development plan includes the provision of electricity and water, the construction of educational and medical systems, and economic development to create sources of income for settlers.

Funding: The funding for the Palestinian campaign takes several paths, in order to disguise it and decentralize risk. The Palestinian Authority’s funding is transferred through a body called the MDLF (Municipal Development and Lending Fund of Palestine). Officially, this is a fund for assistance and loans for municipalities. In practice, it is an external body that helps promote construction in Area C, while circumventing the Oslo Accords, which prohibit the Palestinian Authority from doing so. On the website of the fund we can learn about its funding sources (mainly foreign contributions) and the amount of funding, which totals tens of millions of euros, and about the projects that it has funded, such as the establishment of the school at Khirbet Jinba (MDLF 2016).

Aside from the MDLF, other international organizations fund projects in Area C. A third source of funding is money received directly from donor countries to fund specific projects, with an emphasis on European Union countries or the European Union itself.

However, the official beneficiaries themselves, the region’s residents, are not partners in the funding. It should be emphasized that the information on funding sources is based only on Palestinians sources, on the signs proudly hung, and on official websites.

Law: Judging by the results, as long as the legal process at the HCJ continues, the Palestinian construction continues. With the help of millions of dollars worth of legal guidance over the course of over a decade, the Palestinians are using the HCJ to circumvent the law on firing zones, and the HCJ is unwillingly and unintentionally supporting the developing Palestinian campaign. Former President of the Supreme Court Moshe Landau said that democracy has a right to defend itself even if it must use tools that the law does not explicitly provide it with (HCJ 1/65, 1965). In the case in question, it seems that the situation has been reversed, and in effect the HCJ is preventing democracy from defending itself despite explicit provisions in the law. This is a unique case in which the wager of the campaign is making overt and intentional use of an institutional organ of the rival side in order to advance the campaign that it initiated. The article’s writer asked for the president of the Supreme Court’s response to these claims, but she preferred to remain silent on this matter.

Construction without occupancy: The demographic campaign is based on settlement. Consequently, the construction in the frontier region continues even without demand, similar to a defensive line that is to be taken up when the order is given.

Infrastructure and the theft of resources: The settlement enterprise is fed by water and electricity infrastructure and roadways. This expensive infrastructure is built in violation of the law, and with regard to water, involves the theft of state resources.

The demographic campaign connects two legal points: Three main aims guide the location of the illegal construction in Area C. The first aims to create contiguous Palestinian settlement between polygons of Palestinian settlement in Areas A and B. Connecting these polygons, which are separated by Area C, creates a continuous Palestinian urban area and makes Area C lands in the region into de facto Area B.

The second aim is to encircle and cut off Jewish blocs of settlement, in order to make life difficult for the Jewish settlers in the region and to pressure Israel to give up on these settlements in future negotiations. In addition, the encirclement prevents the continued expansion of Jewish settlement, for example the construction surrounding the settlement of Nokdim.

The third aim is construction that touches on the green line, which has the power to perpetuate this line as a future border. This trend is prominent in Firing Zone 918 and in many regions in the West Bank and in the Jerusalem area.

The humanitarian argument—the “queen of the campaign” The Palestinians use the humanitarian argument as a fig leaf for illegal activity, and it is supposed to increase the legitimacy of their activity while negating that of Israel. The establishment of “sensitive” institutions such as schools, mosques, and medical clinics, even if they stand empty, provides the ultimate “insurance policy” for preventing their demolition. In the struggle between Israel and the Palestinians, the issues of good and bad, just and wrong, correct and mistaken are not relevant, and their strength in the realm of legitimacy is negligible. On the other hand, the narrative of “David against Goliath” characterizes the heart of the issue and is fully utilized by the Palestinians and their supporters in the demographic campaign.

Internationalization of the conflict: Aside from the issue of legitimacy, the Palestinians have a clear advantage over Israel in the international arena. One example of this is the Bedouin village of Khan al-Ahmar, which only few in Israel and abroad had heard about until a decade ago. This is an illegal settlement on state lands. This conclusion was reached by the justices of the HCJ, who, in an unusual move, approved its eviction (HCJ 2242/17, 2018).

At the center of the village, a school whose walls are built out of used tires covered in mud was built by an Italian aid organization. This marginal donation transformed discussion of this remote settlement into an international saga. Many European countries began a vocal campaign against Israel’s intention to carry out the eviction and threatened that this would lead to response measures against Israel. 76 American members of Congress also appealed to the prime minister demanding that he stop the demolition of the village (Dagoni 2018). Later, the European Parliament made a decision stating that the eviction of the village would be considered a violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Meanwhile, the PLO petitioned the International Criminal Court in The Hague claiming that the eviction constitutes a war crime (Levy 2018). In response, the then chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, claimed that it may indeed be a war crime. The international pressure had its effect, and the Security Cabinet has again and again decided to postpone the eviction.

Recruiting support from within Israeli society (“from among the Zionist enemy”) for activity in the territories. Even under left-wing governments, opposition to implementation of restraints on the Palestinian demographic campaign arises that weakens the Israeli system from the inside. The harm can be physical or in the form of propaganda. Israeli factionalism serves the Palestinian demographic campaign in Area C well and is fully exploited by them. For example, when searching for the term Firing Zone 918 on Google, the first website that comes up (as of March 2019) is “Firing Zone 918 | B’Tselem,” which unsurprisingly contains an information page in Hebrew with slogans that perpetuate the Palestinian narrative (B’Tselem 2017). In the list of petitioners against the eviction of Palestinians, one can find the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (but not when it comes to the eviction of Jews) and several Israeli activists with a very specific agenda.

A supportive cognitive and propaganda campaign: The last three principles mentioned (the humanitarian argument, internationalization of the conflict, and recruiting support from within Israeli society) maintain symbiotic relations between them and together synergistically create something greater than them, which can be defined as a “Palestinian propaganda campaign.” The propaganda surrounding the humanitarian narrative helps enlist public opinion in many countries in the world and in parts of Israeli society. This enlistment increases their motivation to be increasingly involved in the conflict. Israeli enforcement actions against this involvement and its consequences leads to diplomatic and political indignation, which translates to an intensification of media resonance in praise of Palestinian construction and in denunciation of Israel. That is, a reactionary cycle emerges that is based on propaganda and continually feeds it, like a dynamo.

The Palestinians Have the Upper Hand

The supreme effort carried out by the Civil Administration’s supervision unit has had quite a few local successes. Without the dedicated work of the supervisors, the state of illegal construction in Firing Zone 918 would have been much worse. But this technical effort is a drop in the ocean compared to the systemic effort carried out by the Palestinians. The budgets of the Palestinian campaign are dozens of times larger than the enforcement budgets of the IDF and the State of Israel with respect to construction in Area C.

The legal effort that supports the Palestinian campaign outweighs the legal effort of the Military Advocate General. The Palestinian cognitive effort that perpetuates the narrative of “humanitarian construction” outweighs the Israeli cognitive effort, which is trying to claim illegal construction. These conclusions, which are unpleasant for Israeli ears to hear, are based more than anything on facts on the ground and judging from the results.

Conclusion

In the first part of the article the demographic campaign was conceptualized. Then two case studies were presented—Tower and Stockade and the Alon Plan—and they demonstrated how demographic campaigns take place in practice. Afterwards the new Palestinian settlement in Firing Zone 918 was studied, and a deductive examination was conducted to locate the foundations of the demographic campaign in this case too. After it was proven that this is indeed a demographic campaign, an inductive process was conducted in an attempt to apply the case of Firing Zone 918 to the entire Palestinian demographic campaign, while emphasizing its unique elements.

Finally, the conclusions of the study were presented. They can be summarized in four main points:

- In border conflicts between countries and nations, demographic efforts are conducted that are waged in an organized fashion as a campaign.

- The new Palestinian construction in Firing Zone 918 is not unplanned chaotic expansion that stems from natural increase, but rather an organized and planned demographic campaign that the Palestinian Authority is waging against Israel.

- The Palestinian demographic campaign has unique characteristics that aim to adapt it to the unique geopolitical reality of this time and place, while attempting to circumvent barriers and maximize opportunities.

- The Palestinians have the upper hand in this campaign. Israel is not waging an organized counter-campaign, and it seems that its response is made up of a collection of technical and local actions that are not coherently managed and lack synergy.

The State of Israel has a clear interest in defeating this campaign, out of a future aspiration to annex Firing Zone 918 or out of a desire to maintain this piece of territory as a bargaining chip in future negotiations, and in the meantime enabling the IDF to use the region for training exercises.

Addressing the Palestinian campaign is a challenge and requires the investment of considerable resources and attention. It is difficult to predict how the IDF will successfully address this campaign, given past experience and the fact that it is facing many important challenges that will always be prioritized over the challenge in question.

The systemic helplessness that Israel suffers in the demographic campaign in Area C requires a conceptual change. Perhaps the solution to this will be the establishment of a special administration for dealing with the issue, within or outside of the IDF. Perhaps the state will need to pass laws to neutralize the “HCJ breach” that the Palestinians have identified, and in any case, it seems that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would do well to display a bit more fighting spirit vis-à-vis the blatant and unilateral European intervention in the region.

Sources

Alon, Yigal. 1968. A Screen of Sand. (Third edition). Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House.

-. 1980. Excerpts from the Alon Plan. Mibifnim 42: 50-51. Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

Arieli, Shaul. 2013. A Border Between Us and You: The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict and Ways of Settling It. Books in the Attic.

Barrett, Deborah. 1995. Reproducing Persons as a Global Concern: The Making of an Institution. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Sociology, Stanford University.

Bar-Gal, Yoram and Arnon Soffer. 1976. Horizons in Geography: Changes in Minority Villages in Israel. University of Haifa.

Ben-Artzi, Yossi. 1988. The Hebrew Moshava in the Landscape of the Land of Israel, 1881-1914. Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi.

Biger, Gidon and David Grossman. April 1992. Population Density in the Traditional Village in the Land of Israel. Cathedra 63: 108-121. https://tinyurl.com/4cnc7csz

B’Tselem. 2017, October 30. Firing Zone 918. https://tinyurl.com/r9ydm3s6

Bystrov, Yevgenia and Arnon Soffer. 2010. Demography of Israel 2010-2030—Towards a Religious State. Chaikin Chair for Geostrategy, University of Haifa (appendix 1, pp. 65-77). https://tinyurl.com/4t7fyuhc

Cohen Yerucham. 1973. The Alon Plan (second edition). Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

Dagoni, Ron. 2018. “76 Democrat Lawmakers to Netanyahu: Stop Destruction of Palestinian Homes in West Bank.” Globes, May 24, 2018. https://tinyurl.com/2hpkdec6

FM 100-5 Operations. 1993. Headquarters Department of the Army. https://tinyurl.com/bdettvtj

Franz, Wallace P. 1983. Maneuver: The Dynamic Element of Combat. Military Review LXIII(5): 2-12.

Friedman, Lior. 2010. “China Marks 30 Years of ‘One-Child Policy.’” Haaretz, October 7, 2010. https://tinyurl.com/4dzvzbkm

Galili, Lily and Roman Bronfman. 2013. The Million that Changed the Middle East—The Soviet Aliyah to Israel. Matar.

Gelber, Yoav. 2018. The Palestinian Time, the Three Years When Israel Turned Gangs into a Nation: Israel, Jordan and the Palestinians, 1967-1970. Dvir.

Gilead, Zerubavel. 1980. Alon’s Speech at the Joint Meeting of the Hakibbutz Hameuchad Central Committee and the Ihud Hakvutzot V'hakibbutzim Central Committee, January 6, 1980. Mibifnim 42: pp. 23-28. Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

Grossman, David. 1994. The Arab Village and its Offshoots. Yad Yizhak Ben-Zvi.

Havakook, Yaacov. 1985. Life in the Caves of Mount Hebron. Ministry of Defense Publishing House.

HCJ 1/65. 1965. Yaakov Yardur v. Chairman of the Central Election Committee for the Sixth Knesset. https://tinyurl.com/4f6yp3nv

HCJ 2242/17. 2018. Kfar Adumim Communal Village for Community Settlement v. Minister of Defense, HCJ 3287/16, HCJ 2247/17, HCJ 9249/17. https://tinyurl.com/yyysuxed

HCJ 413/13 and 1039/13. 2018. Muhammad Musa Shehadeh Abu Aram and 107 et al.; The Association for Civil Rights in Israel; Muhammad Yunis and 252 et al. v. Minister of Defense and Commander of IDF Forces in Judea and Samaria, Respondents’ Response to the Petition. https://tinyurl.com/3yj26f93

Israel Meteorological Service (IMS). n.d. Climate, Precipitation, Multi-Year—1991-2020. https://tinyurl.com/57ur33nz

Khamaisi, Rassem. 2000. “Differences in the Intensity of Renewal Among the Cores of Arab Settlements in Israel.” Horizons in Geography 52: 19-36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23704644

-. 2011. The Book of Arab Society in Israel (4): Population, Society, Economy. Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House. https://tinyurl.com/4uznd7u8

Levy, Elior. 2018. “The Palestinians Petition The Hague Against Israel Prior to Eviction of Bedouin Settlement.” Ynet, September 11, 2018. https://tinyurl.com/5aauc7dy

Marom, Roy. 2008. From Time Immemorial: Chapters in the History of Even Yehuda and its Region in Light of Historical and Archaeological Research. https://tinyurl.com/5n7uj9mx

MDLF. 2016, February 2. MDLF Conducted an Important Visit to Masafer Yatta and a Number of Municipalities in Hebron Governorate. https://tinyurl.com/y2r9ee9k

Naveh, Shimon. 2001. The Art of the Campaign, the Emergence of Military Excellence. Maarchot and the Ministry of Defense.

OCHA. 2013, May. “Life in a ‘Firing Zone’: The Masafer Yatta Communities.” https://tinyurl.com/y6zwtd2e

Order Regarding Security Instructions. 2009. [combined version] Judea and Samaria, no. 1651: 95. https://tinyurl.com/pshp4bf4

Oren, Elhanan. 1987. “The Military and Settlement Attack, 1936-1939.” In The Days of Tower and Stockade, 1936-1939, edited by Mordechai Naor, 13-43. Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi Publishing House.

PCBS. 2018. Census 2017.

Razi, Ephron and Pinchas Yehezkeally. 2006. The World Is Not Linear: Introduction to Complex System Theory. Ministry of Defense

Saint, Crosbie E. 1990. « A CINC’s View of Operational Art.” Military Review, LXX(9): 65-78. https://tinyurl.com/4jmwny43

Steinberg, Mati. 1995. “Birthing the Consequences: The Demographic Factor in the PLO’s View.” In Demography and Politics in Arab Countries, edited by Ami Ayalon and Gad Gilbar, 153-189. Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House.

Supervision Unit of the Civil Administration. 2018, June 12. Presentation of Illegal Construction in Firing Zone 918 (internal document, in the author’s possession).

Turner, Frederick Jackson. 1893. The Significance of the Frontier in American History. State Historical Society of Wisconsin. https://tinyurl.com/3b9hadd5

Zilbershats, Yaffa and Namara Goren-Amitai. 2010. Return of Palestinian Refugees to the State of Israel: Position Paper. (Ruth Gavison, Editor). Metzilah—Center of Zionist, Jewish, Liberal and Humanist Thought. https://tinyurl.com/43fc58rj

Zimmerman, Bennet, Roberta Zaid and Michael A. Weiss. 2006. “The Missing Million: The Arab Population of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.” Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 65, Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University. https://tinyurl.com/5cxxzu7w

Interviews

Ben-Shabbat, Marco. 2019, April 18. Telephone interview on the topic of the construction of illegal infrastructure in the northern Jordan Valley (A. Madanes, interviewer).

Ben-Shabbat, Marco. 2019, January 31. Interview with the director of the supervision unit in the Civil Administration (A. Madanes, interviewer).

Goldstein, Razi and Marco Ben-Shabbat. 2018, June 12. Survey of the illegal construction in Firing Zone 918 (A. Madanes, interviewer).

Gordon, Rodica Radian. 2019, February 28. Conversation with deputy director, Europe department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (A. Madanes, interviewer).

Khushia, Omar Jibril Ahmad. 2019, February 2. Field conversation with a Palestinian at Khirbet al-Markaz (A. Madanes, interviewer, G. Al-Rabia, translator).

Aras, Gasan Ismail Muhammad. 2019, January 26. Field conversation with a Palestinian from Khirbet al-Hilweh (A. Madanes, interview, G. Al-Rabia, translator).

Simona Frankel. 2019, March 3. Conversation with Israel’s ambassador to Belgium (A. Madanes, interviewer).

Sabha, Hamed Ayub Hamed Abu. 2019, February 1. Field conversation with a Palestinian from Khirbet al-Fakheit (A. Madanes, interviewer, G. Al-Rabia, translator).

Sabha, Marwan Yusuf Hamad Abu. 2019, February 1. Field conversation with another Palestinian from Khirbet al-Fakheit (A. Madanes, interviewer, G. Al-Rabia, translator).

List of aerial photos and satellite photos

Aerial photo gid://SHF_181199_S09025_01_130314_097

Aerial photo gid://SHF_181199_S09025_02_130510_155

Aerial photo gid://SHF_181199_S09025_02_130512_156

Aerial photo gid://SHF_181199_S09025_02_130520_160

Aerial photo gid://SHF_021005_M02126_01_100028_014

Aerial photo gid://SHF_021005_M02126_01_100030_015

Aerial photo gid://SHF_021005_M02126_01_100042_021

Aerial photo gid://OGN62_260410_78913_007_145733_0267

Satellite photo gid://OGN61_110518_78913_005_130609_0023

Satellite photo gid://OGN102_300119_78913_000_085720_1577

Satellite photo gid://OGN102_300119_78913_000_085725_1578

Satellite photo gid://OGN102_300119_78913_000_085735_1580

Satellite photo gid://OGN102_300119_78913_000_090634_1702

Satellite photo gid://OGN102_300119_78913_000_090621_1699

Satellite photo gid://OGN102_300119_78913_000_090626_1700

__________________________________

[1] The secrecy relates to the systemic intention, as its physical translation into acts on the ground is visible. In other words, making an overt and declared plan in which the side waging the campaign establishes a widespread settlement enterprise without the consent of the sovereign on the ground and/or contrary to international agreements, could be a double-edged sword and lead to the failure of the campaign and even encourage the opposing side to begin a corresponding campaign.

[2] The Jewish settlement during the British mandate period, which, due to its distribution throughout the Galilee, the valleys, and the coastal plain was called “the N of settlement.”

[3] In addition to the Jordan Valley settlements, dozens more settlements were established in the Jerusalem corridor, in Gush Etzion, and in the Hebron Hills as part of the Alon plan.