Strategic Assessment

The Palestinian-Arab war against the pre-state Jewish community in the land of Israel, and afterwards in the state of Israel, can be divided into a number of stages. Until May 1948 it was primarily a war of militias in the territory of the British Mandate. In the quarter-century after the declaration of the establishment of the state of Israel, it was a total Arab war, in which the Arab world hoped to defeat Israel by conquering the territory. After the failure of the Yom Kippur War, the Palestinian struggle changed its form and transitioned to a combination of terrorism inside and outside Israel, a diplomatic struggle in the international arena and a public relations effort to weaken Israel. In all of these stages, the Arab-Palestinian aspiration remained identical: to foil the establishment of the state of Israel; and after it was established, to oppose its existence within any borders. This article will deal with one facet of the Palestinian struggle against Israel, and that is the use of the Palestinian refugee problem as a demographic tool to eliminate the Jewish state. It will present the Palestinian position on the refugee question during negotiations that took place between the PLO and the PA and Israel, and will clarify the status of the Palestinian demand for massive return of refugees to within Israel (what is known as “the right of return”). This position, and the use of demography as a tool to fight Israel, will be demonstrated via internal documents of the Palestinian negotiation team. Together they present a clear picture of the use of millions of Palestinians, some of whom are fourth and fifth generation descendants of Palestinian displaced persons and refugees from the War of Independence in 1948, as a tool for turning Israel from a state with a clear Jewish majority into a state with an Arab majority, thereby rendering it an additional Arab state in the Middle East.

Key words: The Israeli-Palestinian conflict; the Palestinian refugee problem; demography; the right of return.

Foreword

“We will make the Jews’ lives unbearable using psychological warfare and a population bomb.”

(Yasser Arafat, quoted in Ben-Ami 2016, 214)

The hundred-year Palestinian-Arab war against the pre-state Jewish community in the land of Israel, and afterwards in the state of Israel, can be divided into stages. Until May 1948 it was primarily a war of militias in the territory of the British Mandate. Semi-organized Arab forces tried, and many times succeeded in harming Jewish settlements and their access roads. The declared aim of these actions was to stop the spread of Jewish settlement and immigration (aliyah) to the land of Israel, in order to block the Zionist project and the spread of Jewish presence then taking place in the land (Elpeleg 1989; Kessler 2023; Wasserstein 1991).

In the quarter-century after the declaration of the establishment of the state of Israel it was a total Arab war, in which the Palestinian-Arabs, along with the rest of the Arab world, hoped to achieve their aim of defeating Israel using Arab armies to invade and conquer the territory. The clearest examples of this approach from that period are the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War, during both of which Arab states used their armies to try to vanquish Israel by physically eradicating it (Oren 2002; Morris 2010a; Schiff 1974).

After the failure of the attempts by Arab armies to conquer extensive territories from Israel in October 1973, the Palestinian struggle changed its character again. It shifted to a combination of terrorism inside and outside Israel (Merari and Elad 1986), a diplomatic struggle in the international arena (Heller 2004), and a PR struggle to weaken Israel, for example through economic boycotts and legal struggles in international courts (Herzog 2018). Noteworthy examples of terror attacks during this period were the murder of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics (1972) and the Coastal Road Massacre (1978), followed by the suicide bombings of the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s. Indeed, terror attacks of various sorts are ongoing until today.

During each of these stages, the Arab-Palestinian aspiration was identical: to thwart the establishment of the nation-state of the Jewish people, the State of Israel, and after it was established, to oppose its existence within any borders. From the initial principled rejection of the Balfour Declaration in 1917 on the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in the land of Israel, by way of their rejection of various partition plans for the land of Israel prior to the establishment of the state (such as the Peel Commission in 1937 and the UN Partition Plan in 1947, for example), and up until the refusal to accept concrete Israeli peace proposals in the last two decades (Ehud Barak in 2000 and Ehud Olmert in 2008, for example), the Palestinian-Arabs have consistently refused to agree to any initiative in which Israel remains the nation-state of the Jewish people (Porat 1976, 1979; Morris 2010b).

This work will deal with one aspect of the Palestinian struggle against Israel, which is the use of the Palestinian refugee problem as a demographic tool to eliminate the Jewish state. It will present the Palestinian position as it was asserted in negotiations conducted between the PLO and the Palestinian Authority with Israel over the past three decades, and will clarify the status of the Palestinian demand for massive return of refugees to within Israel (also known as “the right of return”). This position and the use of demography as a tool to fight Israel are demonstrated via internal documents of the Palestinian negotiation team. Together these present a clear picture of the use of millions of Palestinians, some of whom are fourth and fifth generation descendants of Palestinian displaced persons and refugees from the War of Independence in 1948, as a tool for turning Israel from a state with a clear Jewish majority into a state with an Arab majority, and therefore an additional Arab state in the Middle East.

The article will open by describing the Palestinian Arabs in conflict with the pre-state Jewish community and with the state of Israel, and will describe the rhetorical—not fundamental—change in statements by Palestinian leaders from the mid-1980s onwards. Afterwards it will explain the close connection between the demand for the return of Palestinian refugees into the state of Israel and the political aspiration to bring about the end of the existence of the state—a connection that has existed since the end of the 1949 War of Independence. It will then clarify that the demand for return is not an innocent humanitarian demand, but a political act. It will describe one of the ways in which PLO chairman Yasser Arafat misled the international community and caused it to believe that he sought to establish a Palestinian state alongside Israel, rather than in its place. Finally, it will present a description of the considerations and demographic components that tie all the parts of the research together, showing how the Palestinian demand for the return for millions of people aims to influence the character and identity of the state of the Jews, and that this demand is one tool in the Palestinian toolbox in its struggle against Israel.

The article will make use of both the terms “Palestinians” and “Palestinian Arabs.” This is because until the 1960s the Arab residents of the land of Israel were not referred to as Palestinians, but rather as Arabs of Palestine. Today it is almost exclusively acceptable to use the term Palestinians, but that term is anachronistic in relation to the period prior to the 1960s.

Literature review

Until the 1980s historical research on the War of Independence tended to describe the Palestinian Arab departure from the land as the fault of the Arab side, which first rejected the UN Partition Plan and then attacked Israel (Lorch 1958; Slutsky 1972). Calls by Arab leaders to the Palestinian Arab population to abandon their places of settlement, the distribution of false propaganda about atrocities by Jewish soldiers and the flight of the Palestinian Arab population’s leadership—all of these were described as central, if not exclusive, causes for the Palestinian exodus.

The exceptions during this period were the essays by Aharon Cohen (1964), an activist of Mapam (the United Workers Party) and Arab affairs specialist, who also related to actions by forces of the pre-state Jewish community and afterwards by the IDF. An even more critical approach was taken by Rony Gabbay (Gabbay 1959), who first claimed that the responsibility for the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem belonged not only to the Arab side but also to the Jewish one. The opinion that the responsibility for the Palestinian Arab exodus from the land was divided between the Arabs and the Jews was also expressed in other Western works, including the book by Don Peretz (Peretz 1969).

An additional point of reference occurred in the 1980s, when archival files from the War of Independence were revealed. The book by journalist and historian Tom Segev (1984) was the first to relate explicitly to expulsion of Palestinian Arabs by the IDF during the war. There is no doubt that the most important of the research works published during this period was that of historian Benny Morris (1991), who pointed an accusatory finger equally at both sides.

An even more critical stance regarding Israel’s responsibility for the creation of the refugee problem was voiced by Ilan Pappé (Pappé 1992) and by radical leftist activist Simcha Flapan (Flapan 1987), who claimed that the Jewish side was responsible for the absolute majority of departures by Palestinian Arabs. Research works were published in the early 2000s that sought to engage with the critical approach towards Israel, including that of Yoav Gelber (Gelber 2001) and Mordechai Lahav (2000). They both claimed that Israeli expulsion actions were relatively limited, and were not the central and defining reason for the exodus of masses of Palestinian Arabs.

All of these works examined the reasons for the departure of Arabs from the land during the War of Independence and dealt only with the period of the war itself. Later works tried to expand upon the Palestinian refugee problem after the end of the war as well. Jacob Toby (2008) dealt with Israeli policy on the refugee issue during the years 1948-1956, Arik Leibovitz (2015) expanded the discussion up until 1967, and Adi Schwartz and Einat Wilf (2018) analyzed the entire Israeli-Palestinian conflict until the second decade of the twenty-first century through the point of view of the Palestinian refugee problem. They claimed that whatever the circumstances of the departure of the Arabs from the land, they were not fundamentally different from the circumstances in other conflicts around the world, and do not explain the continued Palestinian refugee status so many years after the 1948 war.

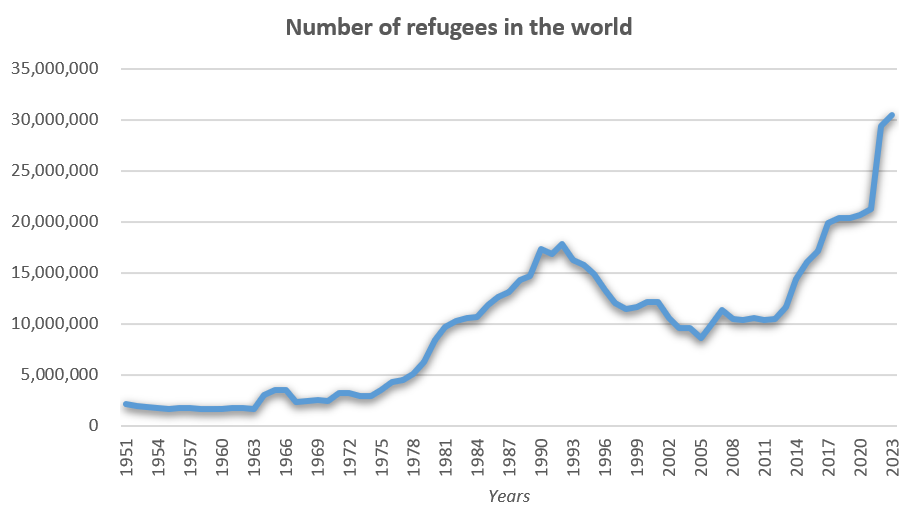

The total number of refugees in the world correlates directly with events in the international arena. As a result, it tends to go up and down in accordance with circumstances. For example, Figure 1 shows that in the 1980s and early 1990s there was a continual increase in the number of refugees around the world, which reached a peak with the collapse of the former Soviet Union and the Communist bloc. Afterwards, from the mid-1990s until the 2000s, there was a decrease in the number of refugees. In the past decade there has been a marked increase in the number of refugees, primarily due to the civil war in Syria and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 1: Number of Refugees in the World | Source: UNHCR

The Palestinian Arab Stance in the Conflict

The stance of the Palestinian Arabs in the conflict with Zionism over the fate of the land of Israel was always very clear. Since the time that the representatives of the Arab public clarified their position to the leadership of the British Mandate in the 1920s (Morris 2003, 72-120), via the statements of Hajj Amin al-Husseini and the heads of the Arab Higher Committee in the 1930s and 1940s (Morris 2003, 121-145), until the foundational texts of the most important representative bodies in Palestinian society— the PLO (Harkabi 1977) and Hamas (Litvak 1998)— this stance has been presented unequivocally. Its core is a complete rejection of Jewish sovereign statehood in the land of Israel within any border, and the belief that the entire land of Israel is destined to be ruled by Muslim Arabs. The PLO charter even explicitly determined that the method to achieve this aim is military.

Since the mid-1980s a certain rhetorical change may be discerned among the leadership of the PLO, primarily when they speak English, and they began to include diplomatic expressions in their speeches and formulate their positions more vaguely. Instead of using the terminology of anti-Western guerillas, as they did in the 1960s and 1970s, PLO Chairman Arafat began to cultivate an image within the international community as a moderate statesman with whom negotiations are possible. This reached its peak with the establishment of diplomatic relations between the PLO and the United States in 1988, within which Arafat undertook to refrain from terrorism and to seek a peaceful resolution to the conflict with Israel (Gresh 1988).

This tactical change in the PLO stance derived from several developments in the local, regional and international arenas. At the local level, the First Intifada was directed and executed by local actors in Judea and Samaria and in the Gaza Strip, not by the PLO leadership who then resided in Tunis. The peace agreement signed between Israel and Egypt in 1979 weakened the determined and unequivocal support of the Arab world for the Palestinian struggle against Israel. And the isolation of the PLO only worsened with their committed support for the leader of Iraq, Saddam Hussein, after his invasion of Kuwait, in opposition to the almost unified stance of the Arab world.

Even more important was the perpetual weakening of the USSR, until its collapse in 1989, which took away the Palestinians’ most important diplomatic, economic and even military support. The disappearance of the PLO’s most significant patron, with the fall of the Iron Curtain and the dismantling of the Soviet bloc, required the Palestinians to rethink their tactics. This strategic weakness, which was noticeable from the mid-1980s, lead the Palestinians to search for new patrons, whom they found in Western Europe and the United States.

However, to win the trust of these new patrons and to enjoy their economic and diplomatic support, the leadership of the PLO understood the need to modify their combative and uncompromising rhetoric against Israel. It was clear to Arafat and the Palestinian leadership that they could not continue to declare publicly that they intended to wipe out the state of Israel and expel its residents. Such rhetoric was an obstacle to the PLO leadership’s ingratiation into the lounges of foreign ministries in European capitals and Washington.

As a result, a sophisticated narrative was crafted involving declarations of commitment to reaching a peaceful resolution with Israel, without abandoning the ultimate goal of turning all of the territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea into an Arab-ruled region. In a paraphrase of the statement by military strategist Carl von Clausewitz that war is simply policy by other means, the Palestinians chose to conduct a diplomatic process as a continuation of their hundred-year war with the state of Israel.

In parallel to these supposedly moderate statements and to opening direct negotiations with Israel in 1993, which supposedly demonstrated recognition of the Jewish state and a desire to establish peaceful relations with it, the PLO continued to walk the tightrope of diplomatic legitimacy versus its ultimate goals. Some of its leaders, including Arafat himself, said in Arabic what they did not want to say in English. In September 1988 Nabil Shaath said that the establishment of a Palestinian state “in some of our homeland, not in all of it” is only an interim stage (Rubin and Rubin 2003, 113). An additional senior PLO figure, Abu Iyad, said in November 1988, immediately after the Palestinian declaration of independence, that “this is the state for the coming generations which is initially small, and if it is Allah’s will—will be big and will expand east, west, north and south […] therefore I seek to liberate Palestine […] one step at a time” (Morris 2003, 565).

Three years later, after the Oslo Accords had been signed, Arafat also told an Arab audience in Stockholm in 1996 that “it is our intention to eliminate the state of Israel and to establish a pure Palestinian state. We will make the Jews’ lives unbearable via psychological warfare and a population bomb […] we, the Palestinians, will take over everything, including all of Jerusalem” [my emphasis] (Stephens 2004). In this way, Arafat gave explicit expression to the use of the Palestinian population and the demographic dimension of Israeli-Palestinian relations as a tool for struggle against Israel.

Even earlier, during a visit to South Africa in May 1994, Arafat gave a speech in a Johannesburg mosque in which he compared the Oslo Accords to the 628 C.E. Treaty of al-Hudaybiya. The reference is to a ten-year peace agreement that the Prophet Muhammad signed with members of the Quraysh tribe, only to build strength and violate the treaty two years later; he then defeated the members of that tribe (Pipes 1999). In an interview with Egyptian television in 1998, Arafat repeated the same idea and explained that a temporary respite from battle is a respected Islamic strategy (McCarthy 2004).

The Palestinian Refugee Problem

At the end of the War of Independence some 600,000-760,000 Palestinian Arabs found themselves outside the lines within which the state of Israel had been established. They were in the Gaza Strip under Egyptian sovereignty, in Judea and Samaria under Jordanian sovereignty, and in the Kingdom of Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria (Morris 1991). In December 1949, the United Nations General Assembly voted to establish the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), in order to rehabilitate Palestinian refugees and integrate them into the economies of the states they had reached (Schwarz and Wilf 2018).

The establishment of UNRWA and the use of the term “Palestinian refugees” predated the adoption of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the establishment of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, as well as the acceptance of the formal definition of who is a refugee. As a result, the status of the “Palestinian refugees” is different from that of refugees everywhere else in the world; they are counted separately and the criteria that apply to all other refugees in the world do not apply to this population. Arab states refused to include the Palestinian refugees in the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

From the beginning the Palestinian Arabs related to the refugee problem as a political issue, and saw it as fundamentally linked to the rejection of the existence of the state of Israel. The refugee problem was never a humanitarian issue of the individual desire of one Palestinian or another to return to his or her home, but rather part of a collective effort to reverse the results of the War of Independence. In the first months after the state of Israel was established, the heads of the Arab Higher Committee saw the return of refugees to Israel as recognition of the existence of the state, and therefore fundamentally opposed it (Schwartz and Wilf 2018, 48). Already in March 1949, the Arab League resolved that “a just and lasting solution to the problem of the refugees will be their return [to their land].” Palestinian representatives who met Israeli diplomats that same year claimed that the problem must be solved by returning them to Israel, and that the refugees retained the right to choose whether to return to Israel or to be rehabilitated in Arab states. In an internal report that the Secretary-General of the Arab League submitted to the League Council in March 1950 the Arab stance was formulated as follows: “The Arab states firmly insist on the return of all refugees who wish to return.” (Schwartz and Wilf 2018, 50)

Certain politicians, and the Arab press, sometimes drew a direct link between the demand for return and the elimination of the state of Israel. In October 1949, Egypt’s foreign minister Muhammad Salah al-Din said: “It is known and understood that the Arabs in their demand for the return of the refugees to Palestine intend to return as the lords of the homeland and not as slaves. To be perfectly clear, they intend to eliminate the state of Israel” (Harkaby 1968). The Lebanese newspaper, Assayad, wrote in February 1949: “We cannot send the refugees back while maintaining our dignity. We must therefore turn them into a fifth column in the battle that still lies ahead of us.” About a year later in the same paper, it was written that the refugees will return “in order to create a large Arab majority, which can serve as a most effective means of reviving the Arab character of Palestine, while creating a powerful fifth column for a day of vengeance and settling accounts” (Schechtman 1952, 24, 31).

Return was therefore not only a geographic return to abandoned homes that remained 20 or 30 kilometers away, but also a return to the time before the Arab defeat in war and the establishment of the state of Israel. Return was not only a physical movement in space but also an erasure of the events that had taken place. Because the Palestinian refugees symbolized the Arab defeat and the victory of Israel, their return was interpreted as an erasure of the defeat and of the victory by the Jewish state. The Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi analyzed Arab sentiment and wrote that the demand for return “began from the assumption of the liberation of Palestine, or in other words the elimination of Israel” (Khalidi 1992, 36). The strategic aim was to return the land to the Arabs, and not just the Arabs to the land.

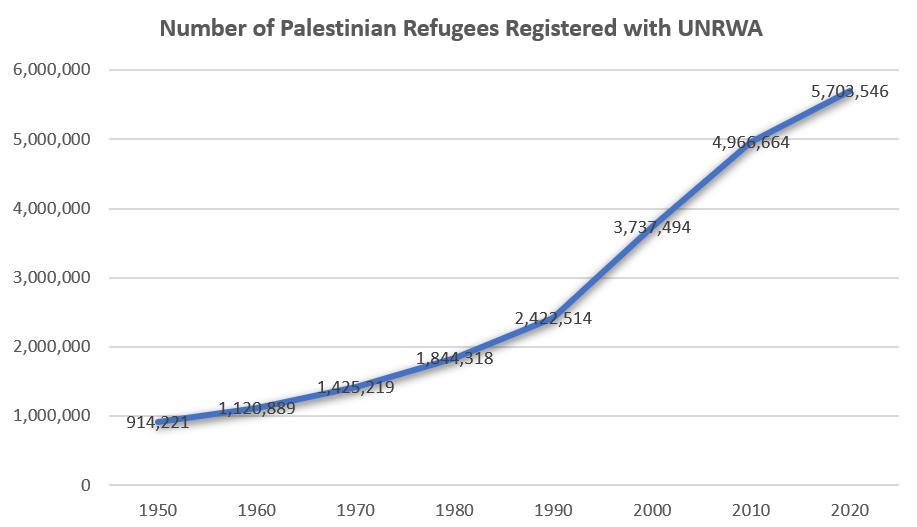

Figure 2: The Number of Palestinian Refugees Registered with UNRWA | Source: UNRWA (In contrast to Figure 1, where the number of refugees fluctuates according to circumstances, note that the number of Palestinian refugees grows continually.)

The Demand for a “Right of Return”

One of the tools Arafat used to fool the international community into believing that he was a real partner for peace was separating the Palestinians’ right to self-determination and their demand for the return of refugees and their descendants. Since the Six Day War, and with the strengthening of the Palestinian national movement, the demand for separate self-determination for the Palestinian people has increased. This is the central reason that the PLO rejected Resolution 242, which did not relate to the Palestinians as a party to the conflict but rather only spoke of the principle of “land for peace.” The Palestinians are not just a group of refugees, Arafat declared at that time, but rather a nation demanding its right to self-determination. During the 1970s and 1980s, Arafat repeated this demand many times (Howley 1975, 73-74).

This right can, in principle, coexist with the parallel right of the Jewish people to self-determination, because if the ultimate aim of the Palestinian people was in fact independence, it could have this alongside the state of Israel and not necessarily in its place. Arafat’s repeated insistence on the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination was understood by many audiences as a retreat from the maximalist aspiration to wipe out the state of Israel. Arafat’s change of image from a terrorist to a statesman, leading his people towards independence, therefore went hand in hand with the emphasis he placed on the right to self-determination (Gresh 1988, 179).

Throughout this period, the refugee question continued to be the most important litmus test for understanding the true Palestinian position, because the demand for the right of mass refugee return cannot be reconciled with the right of the Jewish people to self-definition in its land. Whoever continued to demand that a massive number of refugees should enter the state of Israel was essentially declaring that they do not accept the existence of the state of Israel in the Middle East. Whoever demanded sovereignty in the West Bank and Gaza without giving up on aspirations to return to Haifa, Akko and Jaffa was essentially saying that the change was merely cosmetic, a tactical statement aimed to cleanse Arafat and his organization for Western public opinion, but one that did not encompass a strategic decision to recognize the right of the Jews to a state of their own.

Negotiations with Israel

Direct negotiations between Israel and the PLO, and later the Palestinian Authority, reached a critical point at the Camp David Summit in 2000, during which US President Bill Clinton presented parameters for a solution to the conflict. These parameters included the establishment of a Palestinian state on 97% of the entire territory of Judea and Samaria (the West Bank) and Gaza; the evacuation of most Israeli settlements; the division of Jerusalem according to demographic concentrations; and the division of sovereignty over the Temple Mount. Clinton proposed that Palestinian refugees would be able to return to the Palestinian state and Israel would accept a limited number of refugees, only if it wished to do so (Morris 2001, 671-672).

The Palestinians rejected the proposal. An internal Palestinian document written shortly after the failure of the summit explained the reasons for the rejection of Clinton’s proposals, with the most extensive discussion dedicated to the refugee problem. The document states that “the Palestinians will not be the first people in history to give up on their right of return.” It is also written that the Palestinians demand to return to Israel and not to the future Palestinian state. The document also clarifies the broader context of the Palestinian insistence on return and explains that the Palestinians are unwilling to accept the definition of Israel as the “homeland of the Jewish people” and Palestine as the “homeland of the Palestinian people” because doing so would harm the demand for return. This admission stands in opposition to international community efforts for peace based on the principle of “two states for two peoples” (PNSU 2001).

In the first week of January 2001 the official organ of the Fatah movement published a detailed explanation for the rejection of Clinton’s proposals. “We compromised on territory,” the article states, “but the sacred right of return cannot be given up on. The refugee issue is the heart of the Israeli-Arab conflict.” Refugees have rights, the article also states, and they refuse to resettle in Arab countries. It was also claimed that the refugees will not give up on their right to return to Israel, and that the fact that the Clinton parameters do not include this possibility prevents their acceptance. In order to make it clear that the Palestinians do in fact expect massive return of refugees into the state of Israel, the article refers to Israel absorbing one million new immigrants from the former Soviet Union in the 1990s, and claims that if Israel has the ability to take in so many immigrants, it can also take in the Palestinians (Rubin and Rubin 2003, 326).

In order to remove any doubt, the article explains that “the meaning of non-recognition of the right of return is the continuation of the struggle forever and the blocking of any possibility of coexistence” between Israelis and Palestinians. In the most blatant and clear proof that the aim of the fulfillment of the “right of return” is not humanitarian but political, and that it serves as a cover for the Arab desire to eliminate the state of Israel, the article determines that “the right of return is intended to help Jews get rid of racist Zionism, which forces them to disconnect from the rest of the world.” In other words, the fulfilment of the “right of return” would change the character of the state of Israel, and it would cease to be the nation-state of the Jewish people (Rubin and Rubin 2003, 326).

Demographic Considerations

Around a year after the failure of the Taba talks between Israel and the PA, Arafat published an article in the New York Times in which he presented his vision for an agreement with Israel. “Now is the time for the Palestinians to state clearly … the Palestinian vision,” he writes. At the heart of the article are two central demands—the establishment of a Palestinian state and the return of refugees to Israel. The status of Jerusalem is only mentioned in one sentence (Arafat 2002).

Arafat asks in his article for a “fair” and “just” resolution to the suffering of the refugees, who, in his words, have been forbidden for decades “to return to their homes.” There can be no peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians, he warned, if the legitimate rights of these innocent civilians are not taken into account. Arafat also claimed that the return of refugees is a right guaranteed by international law, but added caveats to this claim and determined that the Palestinians understand the “demographic concerns” [my emphasis] of Israel and know that the fulfillment of return “must be implemented in a way that takes into account such concerns.” The Palestinians, he explained, must be realistic about the demographic desires of Israel (Arafat 2002).

The use of these terms and the explicit reference to demographic “concerns” and “desires” were interpreted in certain circles in Israel and in the world as an elegant way for Arafat to withdraw from the demand for massive return of refugees. According to this interpretation, the fact that Arafat noted that Palestinians understand “the demographic concerns” of Israel shows that they understand that there will not be a mass return. But those who interpreted these statements as giving up on the demand for return ignored the centrality that Arafat ascribed to the refugee problem and its resolution by giving the choice to each refugee and their descendants to return to Israel.

In fact, internal documents of the Palestinian Negotiation Support Unit (PNSU) published in 2011 in the international media revealed that the Palestinian goal was completely different. These are some 1,700 internal Palestinian documents in the English language, which documented a decade of negotiation with Israel and were published by the British newspaper the Guardian and by the Qatari network Al Jazeera in early 2011. The documents were leaked from the office of the chief Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat, who was compelled to resign in light of their publication. Palestinian officials have never questioned the authenticity of the documents nor tried to claim that they were forged or faked (Zayani 2013).

In order to deal with Israel’s claim that it is not capable of taking in so many Palestinian refugees, as doing so would threaten its demographic character, the Palestinians commissioned an independent study that examined Israel’s capacity of absorption. The very fact that the study was commissioned shows that the Palestinians were interested in mass refugee return, as anyone not interested in such return would not try to prove that its implementation is possible. In a confidential document from April 2008 it was written that the aim of the study was to “give scientific backing to the stance of the Palestinian leadership on return to Israel. The study aimed to provide a rational analysis that would support the Palestinian approach of return to Israel, while taking into account Israel’s capabilities for absorption and migration in the past” [emphasis is mine] (PNSU 2008a).

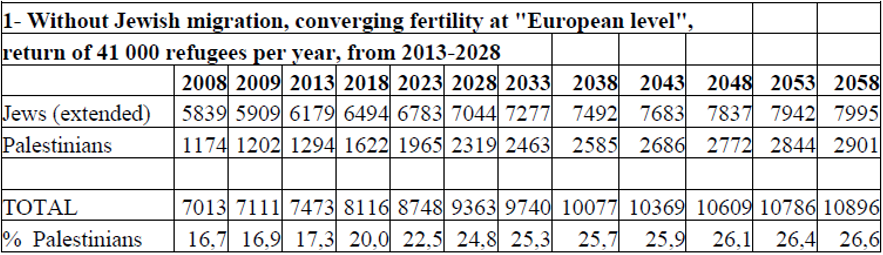

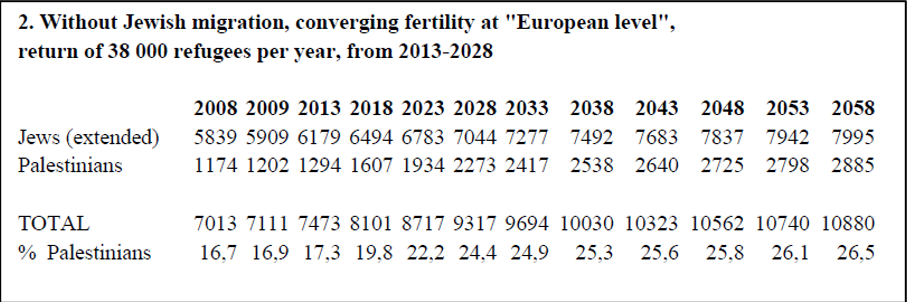

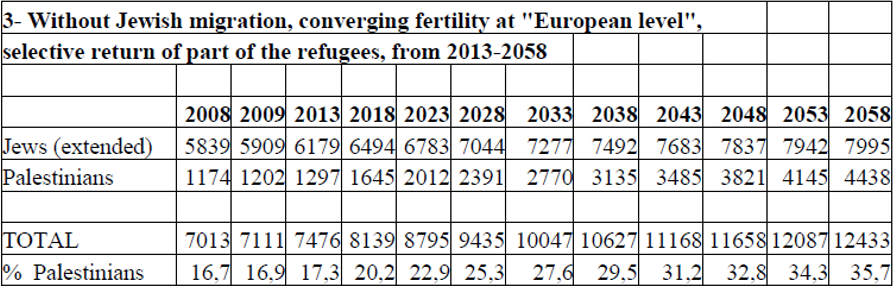

The research was carried out in 2008 by Youssef Courbage, an expert from the French National Institute for Demographic Studies. It examined three scenarios of return to Israel, ranging from several hundred thousand returnees to up to two million, and sought to show that under each of them, Jews would remain the majority within the borders of the state of Israel. In the first scenario (Graph 1), 41,000 refugees would be permitted to return every year for 15 years (between 2013 and 2028) up to a total of 600,000 refugees. In the second scenario (Graph 2), 38,000 refugees would be permitted to return every year for that same period, to a total of 570,000 refugees. In the third scenario, some two million refugees would want to return to Israel (PNSU 2008a).

Graph 1 (Screenshot from the Document): A scenario in which 41,000 Palestinian refugees would be permitted to return to Israel every year for 15 years (between 2008-2013).

According to the scenario described in Graph 1, 41,000 Palestinian refugees would be permitted to return to Israel every year for 15 years. Their number would reach 1.6 million in 2018, in comparison to 6.5 million Jews in that year; 2.3 million in 2028, in comparison to 7 million Jews that year; and 2.9 million in 2058, in comparison to 8 million Jews in that year, or some 27 percent.

According to the scenario described in Graph 2, 38,000 Palestinian refugees would be permitted to return to Israel every year for 15 years. Their number would reach 1.6 million in 2018, in comparison to 6.5 million Jews in that year; 2.3 million in 2028, in comparison to 7 million Jews that year; and 2.9 million in 2058, in comparison to 8 million Jews in that year, corresponding to 27 percent.

According to the scenario described in Graph 3, two million Palestinian refugees would be permitted to return to Israel. Their number would reach 1.6 million in 2018, in comparison to 6.5 million Jews in that year; 2.4 million in 2028, in comparison to 7 million Jews that year; and 4.4 million in 2058, in comparison to 8 million Jews in that year, some 36 percent.

Graph 2 (Screenshot from the Document): A scenario in which 38,000 Palestinian refugees would be permitted to return to Israel every year for 15 years (between 2008-2013).

Graph 3 (Screenshot from the Document): A scenario in which two million Palestinian refugees would be permitted to return to Israel between 2013 and 2058.

The aim of the study was to show that even if hundreds of thousands of Palestinians come to Israel, they would not have the power to threaten the Jewish character of Israel. The research claimed that even in the scenario of two million refugees, the Palestinian population within Israel would amount to a mere 36 percent, and Jews would continue to be the majority. the number of refugees that would come in the first and second scenarios was determined according to the average number of olim (new immigrants) that Israel took in during various periods—the first scenario was based on the average number of immigrants Israel absorbed during the years 1948-2007 (41,000) and the second scenario was based on the average number of immigrants during the years 1996-2007 (38,000). During these years Israel absorbed many immigrants, and the Palestinians tried to claim that if Israel could absorb so many immigrants, it could absorb a similar number of Palestinian refugees.

The fact that the Palestinians related to the absorption of Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union as an indicator of the state of Israel’s capacity for absorption is highly significant, as they ignored the fact that the population absorbed was primarily Jewish (and that the minority who did not identify as Jewish usually had Jewish family members and no desire to challenge the Jewish nature of the state) . Ignoring the national identity of those absorbed by the state of Israel demonstrates a blurring of the national character of Israel—because according to the Palestinian approach it supposedly makes no difference whether the population being absorbed is Jewish or Muslim Arab.

The great significance of the study lies in it being the most detailed indicator of the true desires of Palestinians according to their internal discussions about the possibility of refugees returning to Israel, and that the scale of returnees they were discussing were very large. The number two million is the Palestinian estimate of the number of refugees who would want to return to Israel if they were given the opportunity to do so. From the PNSU documents it is also clear that the estimates in this study were the basis for Arab demands during negotiations with Israel (PNSU 2008b).

In this manner, the veil is lifted on the supposedly comforting phrase “consideration of Israel’s demographic concerns” coined by Arafat in his article, and interpreted since then as Palestinian willingness to accept a symbolic gesture by Israel that would amount to only a few thousand refugees. That was not the case: when the Palestinians say “consideration of demographic concerns,” they mean the return of hundreds of thousands or millions. Indeed, a 2008 document proposes the return of one million refugees (PNSU 2008c).

In parallel to the Palestinian attempt to scientifically support their demand for mass return of refugees, there is evidence in other documents of the rejection of the Israeli demand to accept the Jewish majority in the state of Israel as an established fact. Thus for example, a document from November 2007 states that “if Israel insists on recognition of the demographic character of its state, then the Palestinian team can demand that the status of the entire territory of mandatory Palestine be reopened, because the demand to base the [Israeli-Palestinian] agreement on two ethnically defined national entities undermines the accepted parameters” [my emphasis] (PNSU 2007).

According to the Palestinians, the proposed approach of two nation states brings the discussion back to UNGA Resolution 181 (the partition plan). This plan, in their words, set a boundary while taking demographic considerations into account (for example, where the majority of Jews lived at that time); that boundary was substantially different from the border being considered today. In other words, if Israel demands recognition of its national character, then that means going back to the borders from the 1947 partition plan.

In that same document it was written that it is not acceptable in the international arena to recognize the demographic character of states, and that this Israeli demand does not suit the manner in which states typically conduct themselves. The Palestinians claim that Israel was accepted to the United Nations as a state and not as a “Jewish state,” just as China was accepted as a state and not as a Communist state, and as Pakistan was accepted as a state and not as a Muslim state. The United States and other countries recognized the state of Israel, not the state of the Jews.

The Palestinians understood the Israeli demand to be recognized as a “Jewish state” in its demographic context, because according to the document, such recognition could be interpreted as Palestinians waiving the demand for return. Here the Palestinians also affirmed, in plain English, that their demand for return and their opposition to the existence to the state of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people are dependent on one another.

Summary

There are many ways to wage war on an enemy. The most common and easily identifiable is the use of violence and weapons to defeat the other side. But there are also more sophisticated and surprising techniques, such as using negotiation channels that may serve to continue warfare. An example of the latter can be seen in the Palestinian negotiations with Israel since the 1990s.

Over the years international mediators and Israeli negotiators believed that the Palestinian refugee problem would be solved by allowing those who wish to return the possibility of settling in the Palestinian state that was supposed to be established. The PLO, on the other hand, insisted that every one of millions of refugees and their descendants would be recognized as having a legal right to settle in Israel. Taking into account the demography of Israel, such a massive flow of millions of Palestinians would turn the state of the Jews into a state with an Arab majority. The demand for massive refugee return was therefore opposed to the logic of the two-state solution, which sought to create two nation-states—one for Jews and one for Palestinians.

The demand presented by the Palestinians during the negotiations, for recognition of the “right of return” and the possibility of mass refugee return into the state of Israel, were perceived by certain circles in Israel and the world as a mere bargaining chip, which the Palestinians understood could not be carried out in practice. The underlying assumption in those circles was that the Palestinian commitment to finding a peace deal was real. From there they derived the understanding that the Palestinians did not seriously intend for millions of Palestinians to settle in Israel.

Two axioms led to the adoption of this perspective. The first was correct; it was that the return of refugees is contradictory to a peaceful resolution, as it would negate the Jewish character of Israel. But the second axiom was mistaken—that the Palestinians had in fact abandoned the path of war. The conclusion from these two axioms was that the Palestinians couldn’t possibly seriously intend to insist on the “right of return,” and that they therefore were only using it as a bargaining chip in order to gain other concessions in negotiations. After they achieved such concessions, the Palestinians would relinquish this demand as if they had never made it in the first place.

The findings presented in this work contradict this conclusion. Based on statements by the Palestinians themselves it becomes clear that they relate to the possibility of mass return of refugees into Israel—hundreds of thousands and even millions—as a very realistic possibility. To that end, and in order to strengthen their claims, they commissioned a scientific demographic study that showed that Israel is in fact capable of absorbing such large numbers of refugees.

It is also clear from the documents presented here, how the Palestinians link the demographic and the political components. In other words, there is a direct connection between the demand for return of refugees and the existence of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people. The Palestinians’ refusal to recognize Israel as a Jewish state, together with the insistence on Israeli recognition of the Palestinians’ right to return to the homes that they left during the War of Independence, express the long-running Palestinian position in the conflict with Israel: war against the early Zionist endeavor and non-recognition of the state of the Jews after it was established.

The demand for return is not therefore an innocent humanitarian demand but rather an additional tool—a demographic tool—in the Palestinian toolbox for their hundred-year struggle against Israel.

Sources

Arafat, Yasser. 2002. “The Palestinian Vision of Peace”. The New York Times, February 3, 2002. https://tinyurl.com/4x5t8jy8

Ben-Ami, Shlomo. 2016. Scars of War, Wounds of Peace: The Israeli-Arab Tragedy. Oxford University Press.

Cohen, Aharon. 1964. Israel and the Arab World. Sifriyat Poalim. [Hebrew]

Elpeleg, Zvi. 1989. The Grand Mufti. Ministry of Defense. [Hebrew]

Flapan, Simcha. 1987. The Birth of Israel—Myths and Realities. Croom Helm.

Gabbay, Rony. E. 1959. A Political Study of the Arab-Jewish Conflict – The Arab Refugee Problem (A Case Study). E. Droz, Minard.

Gelber, Yoav. 2001. Palestine 1948: War, Escape and the Emergence of the Palestinian Refugee Problem. Sussex Academic Press.

Gresh, Alain. 1988. The PLO: The struggle Within—Towards an Independent Palestinian State. Zed Books.

Harkabi, Yehoshofat. 1968. The Arab Stance in the Israel-Arab Conflict. Dvir. [Hebrew]

-. 1977. The Palestinian Charter and its Implications. Ministry of Education and Culture. [Hebrew]

Heller, Mark. 2004. “The PLO and the Israeli Question.” In Thirty Years Since the Yom Kippur War: Challenges and the Search for a Solution, edited by Anat Kurz, 43-48. Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies. https://tinyurl.com/mrx5w4nx [Hebrew]

Herzog, Michael. 2018. The International Delegitimization Campaign Against Israel—Analysis and Strategic Directions. The Jewish People Policy Institute. https://tinyurl.com/5ecb8cs6 [Hebrew]

Howley, Dennis C. 1975. The United Nations and the Palestinians. Exposition Press.

Kessler, Oren. 2023. Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield.

Khalidi, Rashid I. 1992. “Observations on the Right of Return.” Journal of Palestine Studies, 21(2): 29-40.

Khalil, Muhammad. 1962. The Arab States and the Arab League: A Documentary Record, Vol. 2. Khayats.

Lahav, Mordechai. 2000 Fifty Years of Palestinian Refugees, 1948-1999. Self-published. [Hebrew]

Leibovitz, Arik. 2015. The Sacred Status Quo: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Issue, 1948-1967. Resling. [Hebrew]

Litvak, Meir. 1998. “The Islamization of the Palestinian‐Israeli Conflict: The Case of Hamas.” Middle Eastern Studies, 34(1): 148-163. DOI:10.1080/00263209808701214

Lorch, Netanel. 1958. The History of the War of Independence. Masada. [Hebrew]

McCarthy, Andrew C. 2004. “The Father of Modern Terrorism; The True Legacy of Yasser Arafat.” National Review Online, November 11, 2004. https://tinyurl.com/2mrcu2yb

Morris, Benny. 1991. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem 1947-1949. Am Oved. [Hebrew]

-. 2001. Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-1999. Vintage.

-. 2003. Victims: The History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict. Am Oved. [Hebrew]

-. 2010a. 1948 – The History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Am Oved. [Hebrew]

-. 2010b. One State, Two States: Resolving the Israel/Palestine Conflict. Yale University Press.

Merari, Ariel and Shlomi Elad. 1986. Terrorism Abroad: Palestinian Terror Overseas 1968-1986. Hakibbutz Hameuchad and Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies. [Hebrew]

Oren, Michael. 2002. Six Days of War – The campaign that changed the Face of the Middle East. Dvir. [Hebrew]

Pappé, Ilan. 1992. The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict: 1948-1951. I.B. Tauris.

Peretz, Don. 1969. The Palestine Arab Refugee Problem. Rand Corporation. https://tinyurl.com/4ucaysvd

Pipes, Daniel. 1999. “Lessons from the Prophet Muhammad’s Diplomacy.” Middle East Quarterly, 6(3): 65-72.

PNSU. 2001. Memorandum: President Clinton’s proposals. NSU No. 120. January 2, 2001. https://tinyurl.com/yumjyrhw

PNSU. 2007. Memorandum: Strategy and Talking Points for Responding to the Precondition of Recognizing Israel as a “Jewish State.” NSU No. 2021. November 16, 2007. https://tinyurl.com/5ujkaajc

PNSU. 2008a. Israel’s Capacity to Absorb Palestinian Refugees – Demographic Scenarios 2008-2058. NSU No. 3028. https://tinyurl.com/yc764jhc

PNSU. 2008b. Palestinian Talking Points Regarding Israeli Proposal – September 2008. NSU No. 3328. https://tinyurl.com/2d46v5sm

PNSU. 2008c. Note on Refugee Calculation. NSU No. 2364. https://tinyurl.com/2a35s2bm

Porat, Yehoshua. 1976. The Growth of the Arab Palestinian National Movement 1918-1929. Am Oved. [Hebrew]

-. 1979. From Riots to Rebellion: The Palestinian Arab National Movement 1929-1939. Am Oved. [Hebrew]

Rubin, Barry and Judith Colp Rubin. 2003. Yasir Arafat: A Political Biography. Oxford University Press.

Schechtman, Joseph B. 1952. The Arab Refugee Problem. Philosophical Library.

Segev, Tom. 1984. 1949: The First Israelis. Domino. [Hebrew]

Schwartz, Adi and Einat Wilf. 2018. The War of Return: The Battle over the Palestinian Refugee Problem and How Israel Can Win. Kinneret Zmora Dvir. [Hebrew]

Schiff, Zev. 1974. The Earthquake in October. Zmora Bitan. [Hebrew]

Shemesh, Moshe. 1994. “The Sinai Campaign and the Suez Campaign: The Political Background in the Middle East 1949-1956.” In Studies in the Rebirth of Israel, vol. 4, edited by Pinchas Ginosar, 66-116. The Ben-Gurion Heritage Institute. [Hebrew]

Slutsky, Yehuda. 1972. The History of the Hagana, vol. 3. Am Oved. [Hebrew]

Stephens, Bret. 2004. A Gangster with Politics. Wall Street Journal, November 5, 2004. https://tinyurl.com/wr2x859x

Toby, Jacob. 2008. On the Threshold of Her House: The Formulation of Israel’s Policy on the Palestinian Refugee Issue, 1948-1956. The Ben-Gurion Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism and the Herzl Institute. [Hebrew]

Wasserstein, Bernard. 1991. The British in Palestine: The Mandatory Government and the Arab-Jewish Conflict 1917-1929. Blackwell.

Zayani, Mohamed. 2013. “Al Jazeera’s Palestine Papers: Middle East Media Politics in the Post-WikiLeaks Era”. Media, War and Conflict, 6(1): 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635212469910