Strategic Assessment

The sense of victory after the Six Day War of June 1967, was quickly replaced by concern over the demographic challenge of approximately one million additional local Arab residents, and especially the governing of extensive territories in the West Bank. The government, headed by Levi Eshkol, made a decision to settle Israeli citizens in the West Bank as soon as possible, to create facts on the ground through territorially contiguous settlement and demographic change, and to ensure strategic depth and maximum security on the country’s new borders. Connecting the mountain ridge and the Jordan Valley in the West Bank to the narrow coastal strip, which was an important yet vulnerable part of Israel before the war, could provide secure borders. In effect, the new reality on the ground dictated a demand for immediate state action. Four proposals for addressing the newly-added territory and its local Arab population were submitted to the government. Three of them we instigated by government ministers: Yigal Allon, Israel Galili, and Moshe Dayan. But none of the proposals was implemented. The fourth proposal came from the palace of King Hussein in Jordan—a federation plan. His proposal was rejected, and a decade later the king announced a unilateral separation of the West Bank from Jordan. Since the end of the war, Israel has administered the held territories and their local population, whose national and religious identity differs to Israel’s. The administration of the territories has led to geopolitical changes and also to shifts within Israel’s military, social, and economic spheres.

Introduction

The reality of controlling the West Bank territories after the Six Day War led to many dilemmas among decision-makers in Israel. The need to cope with about a million Arab residents and to attend to all of their needs, including military, diplomatic, legal, political, civil, economic, and humanitarian issues, led to the establishment of a military governorate in the territories. During the two decades after the war, dozens of Jewish settlements, most of them agricultural, were established in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. They created a new geopolitical, topographical, and strategic reality in Israel and in the West Bank. Three main motives shaped Jewish settlement in the West Bank. One was security—a security concept that advocated defensible borders and control of the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge above it, which provides strategic maneuverability. The second motive was demographic and emphasized the Zionist vision of settling all of the Land of Israel, creating territorially contiguous settlement, creating a Jewish demographic reality, and agricultural work. The third motive was economic and sought to integrate the population of the held territories as cheap labor in the Israeli market on one hand, while ensuring their livelihood and agricultural production as well as developing their economic independence on the other hand.

Coping with the territories and their residents led to disagreements in the government and directly affected public opinion in Israel, the West Bank including its local residents, Jordan, and around the globe. At the beginning of July 1967, Prime Minister Levi Eshkol and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan established professional government committees to propose plans for the development and management of the local population in the held territories (ISA, 18/7309). Many professional committees were established, including the directors-general committee, which included the directors-general of all of the government ministries and representatives of the army, in order to join forces and comprehensively address all relevant areas of life. Another committee discussed plans for the development of the held territories, which quickly received the name “the professors’ committee,” after its scholarly members. The committee was in charge of preparing concrete plans to deal with the local population in the held territories (Brown 1997; Gazit 1985).

These new government committees tackled issues concerning the West Bank and focused in particular on many demographic questions (ISA, 18/7309). All areas of life came up for discussion, including the movement of residents and agricultural goods from the West Bank to the East Bank, the employment of local residents throughout the West Bank and by various bodies in Israel, education and health, rehabilitating villages, refugees, and family reunifications. After the unification of Jerusalem two weeks after the end of the Six Day War, at the end of June 1967, the Israeli government decided to grant permanent residency to East Jerusalem residents and to enable them to continue to simultaneously hold Jordanian citizenship (Ramon and Ronen 2017). This decision applied only to the residents of East Jerusalem and not to those of the rest of the West Bank.

This article limits its scope to the first decade after the war, to focus on events in Israel during this period and on the demographic changes that occurred. In the census that was submitted to the government in November 1967, about a million residents were counted in the West Bank territories. The Israeli government was not presented with a demographic forecast regarding the growth of the population in the held territories in the future. The decision-makers in this decade believed that they should focus on strategic and security aspects and ignored the future consequences of the demographic dimension. The census conducted at the end of 1977 showed that the number of residents in the held territories in the West Bank had grown by 20%, to about 1.2 million people (ISA, 3/12055). The number of people from the territories employed within pre-1967 lines that year was estimated at about 120,000. These figures indicate the growth of the local population and its integration in employment in the Israeli economy.

This article shines a spotlight on the first decade after the Six Day War, during which several proposals for addressing the West Bank territories and their local residents were submitted to the government by ministers. The article also presents King Hussein of Jordan’s counter-proposal for administering the West Bank as a Jordanian federation, a kind of “mirror proposal” that emphasizes the differences between each side’s considerations regarding the territories and their residents. The innovation in this article is in examining why such a large number of proposals were made, what characterizes them, and whether the proposals were accepted and carried out, in part or in full. The main question that stems from the various proposals and the new demographic reality concerns whether, in the first decade after the Six Day War, Israel’s governments even formulated a policy on the country’s borders and the population that would be included in them? The article’s primary concern is to examine and compare the four proposals, and to consider their uniqueness and trajectories with an emphasis on the demographic issue.

When a country experiences demographic changes that stem from population transitions and involve military rule, it produces complex challenges. For the sake of this discussion, the article contains a comparison table that examines the proposals based on their similarities and differences and points out the implications that arise from this analysis. The purpose of the comparison is to create a clear distinction between the various proposals and to discuss their nature. The importance of the comparison is in shining a spotlight on the various possibilities that were presented to Israel’s government to address the demographic dimension in the West Bank territories from 1967 to 1977. Given the proposals that were submitted to Israel’s governments, the article answers the questions: Why did the decision-makers refrain from officially adopting at least one of the proposals, and was a policy even formulated on the country’s borders and the population that would be included within it?

In the table, a special emphasis was placed on the demographic dimension of the four proposals, in particular in the three Israeli proposals that were submitted to the government. None of the proposals looks at the future demographic growth of the Jewish and local Arab population. It is clear that Israel’s governments decided not to decide on the issue of control of the West Bank territories. Control of the territory and its Palestinian residents blinded the eyes of the leadership in Israel, which saw control of the West Bank and the mountain ridge as a strategic objective for ensuring and expanding Israel’s defensive borders. The government saw holding onto the land and creating facts on the ground as a national objective and an incentive for quick Jewish settlement in the West Bank, while ignoring the local Palestinian demography there. In the decade discussed, Israel’s governments ignored the demographic dimension and its consequences for the future reality of the West Bank in terms of the demographic growth of the Jewish and local Arab population. They refrained from making decisive decisions regarding the proposed plans, as detailed in the article. In the eyes of Israel’s governments, the only way to cope with the demographic dimension was Jewish presence throughout the West Bank. By creating territorially contiguous Jewish settlement and ensuring a hold on the land, a new reality emerged of Jewish settlement throughout the West Bank. Decision-makers in Israel believed that this was the only way to control the territory and to ensure a “human shield” for the state’s borders.

The Allon Plan

In the days after the Six Day War, a census was conducted that aimed to estimate the local population in the held territories, in order to improve the government’s ability to manage the demographic challenges in the wake of the war. A document from the 1967 population census shows that the distribution of local residents in the held territories immediately after the war was as follows: the Golan Heights—6,400; in the Gaza Strip the number of residents was about half a million as detailed below: northern Sinai—33,000; Gaza—119,000; Jabalia—44,000; Deir al-Balah—18,000; Khan Yunis—53,000; Rafah—50,000; in the refugee camps there were about 175,000 residents. In the West Bank there were about 600,000 people as detailed below: the Nablus and Jenin district—226,000; the Tulkarm district—79,000; the Ramallah district—94,000; the Jericho district—9,000; the Jerusalem district—27,000; the Bethlehem and Hebron district—162,000. The census estimated a total of about one million local residents throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip (ISA, 7/2608).

In order to cope with the demographics of the territories, on June 26, 1967, Labor Minister Yigal Allon submitted a document to Prime Minister Eshkol titled, “The Future of the Territories and Ways to Handle the Refugees” (ISA, 16/7309, 20/7309; Yad Tabenkin, division 41, container 9, file 5; Mileer-Katav 2012). The document includes a peace plan and arrangements regarding the West Bank and Gaza, with an emphasis on finding political, security, employment, and demographic solutions in the Golan Heights and Sinai too. The plan was named the “Allon Plan,” after its initiator. Revised versions from other dates, including February 27, 1968, December 10, 1968, January 29, 1969, and September 23, 1970, and the final version, from July 17, 1972, which was brought to the government for discussion, were presented to the government of Israel (ISA 13/7022, 14/7022; Yad Tabenkin, division 41). On September 15, 1970, on the eve of Prime Minister Golda Meir’s trip to the United States, Allon submitted a revised version of his plan.

The uniqueness of the Allon Plan was that its principles were implemented on the ground, and it was discussed in political forums inside and outside of Israel with foreign bodies, namely, official representatives of the United States, foreign governments, and King Hussein of Jordan. The plan itself, despite its numerous incarnations, was not accepted as an official program by the government of Israel due to internal and foreign policy issues. Yigal Allon honored Prime Minister Eshkol’s requests not to put his proposal to vote in the government, out of concern that it would arouse strong opposition. So Allon only presented it in meetings of the Alignment Party, where the plan was accepted as a possible proposal for action and included in the party’s platform for the Knesset elections.

The plan’s weakness was that it only took into account Israel’s position on the held territories, but did not examine whether the local population wanted to be under Israeli or Jordanian sovereignty. Allon also did not examine Jordan’s position and its attitude towards bringing the Arab population in the held territories under Israeli sovereignty. Only after the publication of his plan did Allon try to convince the Jordanians to accept Israel’s position on the issue, but he did not succeed. In effect, Allon foresaw the demographic changes that would take place in the territory over the course of several decades; that as time went by, the population would grow, the demography would transform, and Israel would face a fundamental issue of ruling over millions of Palestinians within its borders. In his vision, Allon wanted to create a complete separation between the local Palestinian population and the Israeli population. This separation, as Allon presented in his plan, was supposed to ensure the independent existence of the Palestinians on one hand, and Israel’s broad security control of the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge on the other hand, while strengthening Israel’s hold on the land and implementing the principle of settlement. The plan as presented in each of the drafts was not accepted as the government’s official policy, though Allon implemented the main aspects of his plan in practice via Jewish settlement in the held territories.

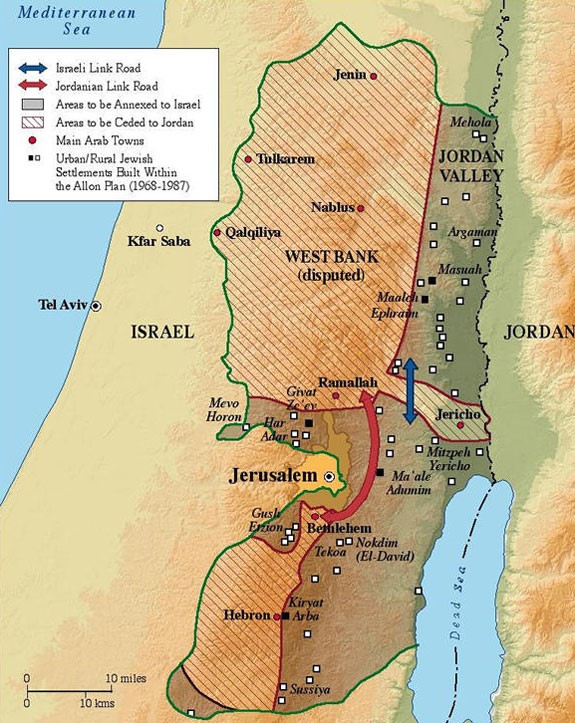

The main aspects of the plan are based on the idea of territorial compromise. At the center was the need to hold onto the areas that were militarily important to Israel, such as the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge above the valley. Furthermore, the plan proposed restoring Arab rule over regions that were conquered during the war and were densely populated by local Arab residents, because these territories were not militarily essential to the country and could even be a demographic stumbling block to future Israeli sovereignty. The plan’s basic assumptions were, firstly, that peace agreements with the neighboring Arab countries and the Palestinians were possible and necessary; and that it was essential for Israel to make an immediate decision on the political future of the territories conquered in the Six Day War. Second, that maintaining the geostrategic integrity of the Land of Israel would enable defensible borders and avoid war in the future. Third, that maintaining a Jewish majority in the State of Israel would ensure the existence of a democratic Jewish state according to the Zionist vision. Fourth, that the Palestinian people could achieve an independent national life without harming the State of Israel’s security. They would be able to choose political relations with Jordan or with Israel. Regarding the refugee problem, the Plan suggested the pursuance of an Israeli initiative to resolve the problem as both a humanitarian and a political issue, and an Israeli need no less than an Arab need.

The plan presented border arrangements based on the Green Line: Israel’s eastern border would be the Jordan River and the line going through the center of the Dead Sea from north to south, and continuing with the British Mandate[1] border through the Arava. West of the Jordan river, a 15-kilometer-wide strip would be added to the State of Israel and become a part of it. “In the area of the Judean Dessert, including Kiryat Arba, the width of the strip will reach 25 kilometers, and will serve as a link connecting the Negev and the Jordan Valley. In the area of Jericho there will be a corridor for passage from the East Bank of the Jordan to the West Bank. There will be a strip for passage between the West Bank and the Gaza region, and it will enable a connection between the population of the West Bank and the population of Gaza and free passage to a port in Gaza. The entire Jerusalem region was to be added to the State of Israel (Yad Tabenkin, division 8-15). In the areas densely populated by Arabs in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, negotiations would be held between the State of Israel, the residents, and the Arab countries, in which an agreed government would be established. Regarding the remaining borders, it was determined that only necessary border adjustments would be made (Yad Tabenkin, division 8-15).

Map of the Allon Plan | Source: Center for Israeli Education, http://tinyurl.com/tp5bn3wc

Allon was determined to prove to the government and the public in Israel, to the refugees, and to the watching eyes of the world, that it was possible to resolve the demographic problem and the refugee problem. He proposed starting with the planning of one model Arab refugee village, in the West Bank or Sinai. The construction was supposed to be at the expense of the State of Israel without requests for economic assistance from other countries. However, according to ’Allon’s plan, responsibility for the livelihood and rehabilitation of the refugees would fall on UNRWA’s shoulders.[2] Allon also included another important proposal—to establish “a single national authority that would coordinate all of the research and activities in the territories” (ISA 16/7309, 20/7309, 10/7032; Yad Tabenkin, division 8-15).

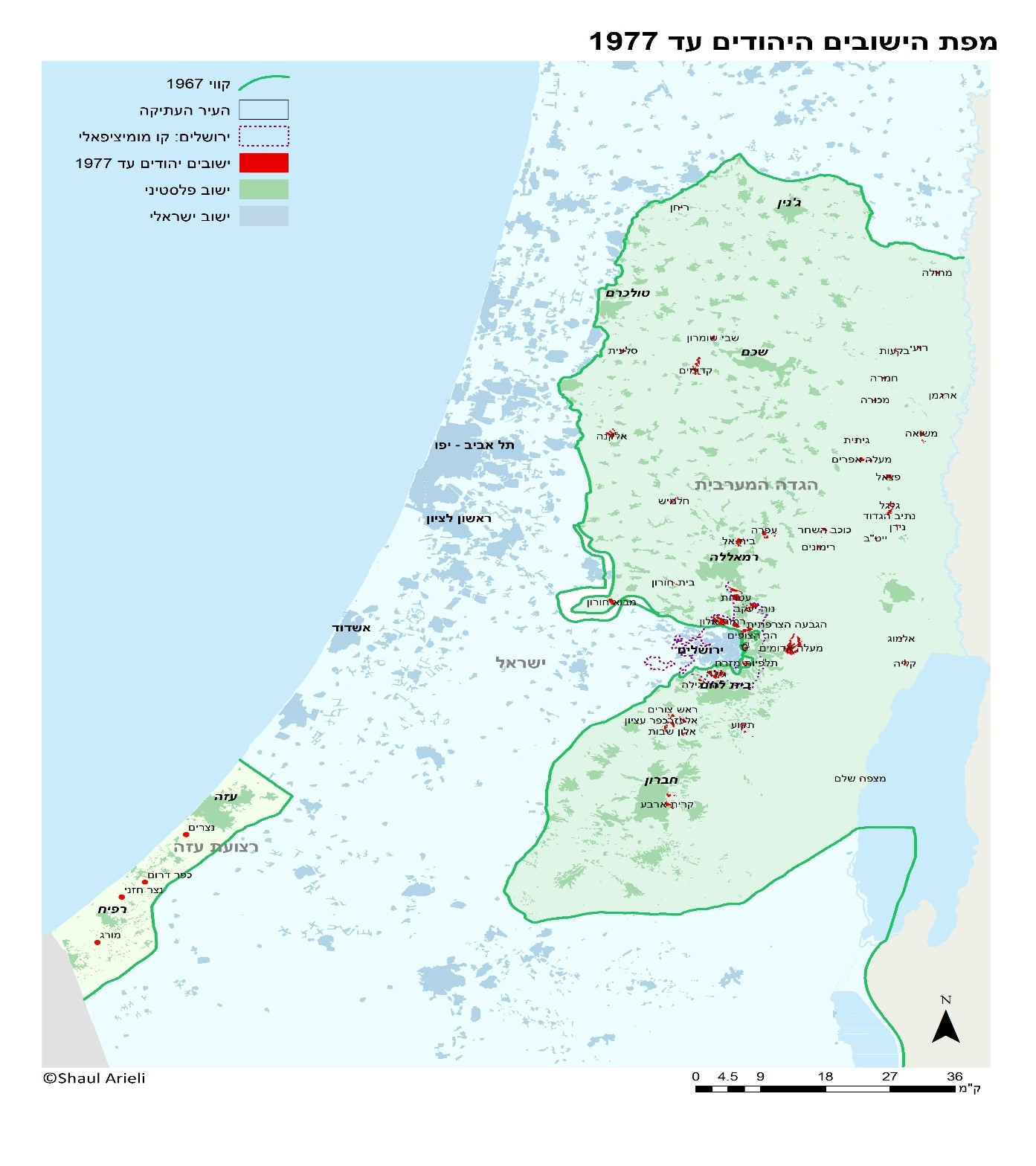

The government of Israel did not officially approve Allon’s suggestion, but in the ensuing years acted according to it nevertheless. From 1968 to 1977, 76 settlements were established according to the outline of the Allon Plan, throughout the new territories added to the State of Israel following the war. Yigal Allon submitted another amended proposal to the government in February 1968, in which he specified the need to immediately settle the Jordan Valley in order to create the presence of Israeli civilian settlements in addition to the military presence there. He believed that by establishing a few security settlements in the Jordan Valley, Israel would have territorial contiguity and military strength. At the same time, the Jewish demographic reality throughout the West Bank would completely change the map of the territory and all future reference to it. In his words, “an Israeli civilian and military presence in the Jordan Valley is a kind of border adjustment that has no replacement. And the location of the settlements needs to be planned such that all options will remain open for various solutions” (ISA, 16/7309).

As for Jerusalem, Allon sought to place the need to expand construction there on the government’s agenda. In May 1969, he wrote another proposal for the government in which he sought to immediately expand the municipal construction area of the united Jerusalem.[3] The minister also demanded the application of Israeli law and municipal jurisdiction to the areas added after 1967. Allon’s explanation of the importance of his proposal was the attractive charm of the city in the eyes of Israelis and new immigrants wishing to make their homes there. In his words, “Hence the city’s master plan should be based on suitable land in terms of size, and we must immediately start to locate new projects in the city of Jerusalem” (ISA, 16/7309, 10/7032).

As for the Golan Heights, Allon wrote that Israel should hold a position on the border with Syria. The country’s main water sources are located in the Golan Heights, providing water to southern Israel too. Hence the Golan, the Upper and Lower Galilee, and the Jordan Valley should be protected. Allon planned a line of topographical outposts that would block paths of advancement towards Israeli territory and provide cover for offensive deployment when needed. The line was also supposed to provide early warning of the advancement of enemy aircraft from a great distance (Kipnis 2009, 116-129).

On the eve of Prime Minister Golda Meir’s trip to the United States to meet with President Nixon in September 1970, Allon submitted another document to Meir that included maps. In the document’s introduction he wrote: “The proposed border lines, along most of their length, are the red line that we must not give up on, and I see them as the only alternative to the Rogers Plan”[4] (ISA, 16/7309, 10/7032).

Allon again specified what in his opinion were the principles of the future map of Israel and of the country’s borders, which would be required in any peace agreement. First, the border lines must be strategically defensible. Second, a demographic aspect should determine and secure national borders whose scope are enshrined in the historic moral right of the People of Israel to the Land of Israel. The third principle explained that the border lines must ensure the Jewish character of the State of Israel, and be politically realistic. Allon emphasized that any border must take into account strategic requirements as a first priority. He also added that as long as there was no peace agreement between Israel and its neighbors, Israel would continue to hold the ceasefire lines. These principles recur in various formulations, but the core elements remain.

Allon also discussed the issue of instability in the territories, the danger of influence of a hostile power, and explained that the Plan might not allow for Israel to maintain military bases or patrols in the territories within the area of Arab sovereignty. For this reason, he did not see these as permanent status agreements. The fourth principle addressed the controlled demilitarization of strategically vital territories and was supposed to serve as one of the foundations of the security arrangements. But demilitarization of such territories was not to serve as a replacement for real defensible borders, which would remain under Israeli control in terms of both legal sovereignty and military control. The fifth and most important principle from Allon’s perspective was that the borders must be based on a topographical system that was supposed to be a permanent barrier for defensive deployment against mechanized ground forces and a base for Israel forces’ control of the territory. The borders were supposed to provide the country with reasonable strategic depth and to ensure a warning system that would warn of the approach of enemy aircraft as early as possible. Allon also noted the problem of terrorism and sabotage and added that the possibility that guerrilla warfare and even acts of terrorism and sabotage could develop, should be taken into account (ISA 16/7309, 20/7309, 10/7302, 14/7022, 13/7022).

The Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, 1967-1977 (partial list) | Source: Shaul Arieli, http://tinyurl.com/43d6ujd7

Ten years after he formulated the plan, Allon was asked if he still believed in it as a suitable solution to the reality in Israel (Yad Tabenkin, division 15). His response was resolute that it stood the test of time (Zak 1996, 21-29; Yad Tabenkin, division 15, container 4). Even a decade later, Allon was convinced that his proposal was an opportunity not to be missed. It would grant Israel the security it needed, would enable talks and negotiations with the neighboring countries to the point of understandings and agreements to bring about regional peace, and would give the developing Jewish settlements a demographic advantage over the existing Arab settlements and those that would be established in the future. The plan, as he laid it out in the media, was entirely rational and based on three basic facts: topography, demography, and strategy. According to Allon, there had been no change in the three components since he submitted the plan in June 1967.

In Allon’s opinion, the geography remained as it had been since biblical times, the demography had changed for the worse, and the technological development of weapons strengthened the strategic thesis. The plan was relevant because it displayed an understanding of the territorial interests of the Arab countries, presented a constructive response to Palestinian calls for self-government and of course to the security needs of Israel. Allon did not see any alternative to the plan, unless Israel decided to rely on foreign guarantees for its security and as a replacement for self-defense. He warned against this in every possible way. Allon also emphasized that he supported negotiations without preconditions with the representatives of the Arab countries and local residents, knowing in advance that each side could put forward proposals that were unacceptable to the other side, and that whoever recognized Israel’s right to defend itself would sooner or later come to terms with border adjustments to enable this. Allon added that Israel did not conquer the West Bank from the Palestinians but from the Kingdom of Jordan, which attacked us. “During the 19 years of rule by Arab countries in the West Bank and Gaza, they did not fulfill the Palestinian idea. Therefore, let us not be holier than the pope,” Allon said (Yad Tabenkin, division 15).

Minister Israel Galili’s Plan for Action in the Held Territories: The Galili Initiative

On March 27, 1972, Minister without portfolio Israel Galili wrote a letter to Prime Minister Golda Meir in which he compiled several proposals for the administration and management of the held territories and their population. In this letter, as in previous letters and in many written after it, Galili laid out the dilemmas facing the State of Israel in handling the new territories and their demographic challenge. When he wrote the letter, there was not yet an established, organized procedure for governing the territories. This document, together with other documents that Galili drafted and submitted to the government, were the basis for the official document that he wrote more than a year later, prior to the elections to the Eighth Knesset in December 1973, which was called the Galili Document after its author. This document comprehensively details in fifteen points how to handle the population and the held territories. Galili drafted the final document as a compromise formula between his original document and the proposal of government minister Dayan and the rest of the members of the government, because there was a need to approve the Labor Party’s platform prior to the elections. The Galili Document presents a compromise without “winners and losers.”

In March 1972 Galili approached Prime Minister Golda Meir and said that it is essential in his view that representatives of the State of Israel—ambassadors and other diplomats—be sent an authorized policy briefing on the issue of borders. The briefing should emphasize first and foremost the need for defensible borders. This entails Israel’s demand for new, permanent borders, which would be defensible, recognized and enshrined in peace agreements. Galili also stated that Israel would not return to the 1948 ceasefire lines and to the international border of the British Mandate. The demand for changes applied to the borders with Egypt, Jordan, and Syria and Israel’s aspiration was that they could be achieved in negotiations. Later Galili clarified his intent and said that Israel does not only mean to have a “presence” or “lease” the land beyond the previous borders, but exert sovereignty there (Traube 2017, 407-431; Kipnis 2009, 129-133).

Galili also emphasized that in addition to determining new borders, Israel would demand various security arrangements, such as demilitarization of certain regions. The minister noted that as is written in the founding guidelines of the State of Israel, Israel aspires to peace agreements with the neighboring Arab countries. However, without peace, “the State of Israel will continue to fully maintain the situation determined by the ceasefire agreements following the Six Day War. Israel will fortify its standing in every ceasefire region as demanded by its security needs and the development of the country” (ISA, 8/7067).

The second element of the briefing concerned the peacetime border between Israel and Egypt. The previous border line, meaning the international border of the British Mandate, would be moved south into Sinai. The Gaza Strip would be an inseparable part of the State of Israel, and Israeli control of Sharm El Sheikh would continue. In addition, territorial contiguity would be created between Sharm El Sheikh and the State of Israel, to a certain point on the Mediterranean coast. Galili noted in the document that the width of the strip had not yet been determined, and it also discussed the demilitarization of certain Egyptian areas in the Sinai region. Galili mentioned that Israel did not intend to hold onto all of Sinai, nor even the majority of it. The third aspect addressed Israel's border with Jordan. Galili’s communication with Prime Minister Meir clarified that the government had not yet decided on a cohesive territorial plan; it had not adopted the Allon Plan, but neither had it chosen any other plan.

In effect, the government had not yet decided its stance on the political border with Jordan, and in practice it intended considerable changes and not only minor adjustments. Galili emphasized that a united Jerusalem is the capital of the State of Israel and that the rights of members of all religions with respect to the holy places would be recognized. He also added that the Jordan River would be the security border and the Jordanian army would not cross into the West Bank. As for the demographic aspect in the Jordan Valley and settlements up to the area of Ein Gedi, aside from the corridor connecting Jordan to the Arab population centers in the West Bank, the settlements would be an inseparable part of the State of Israel. The minister stated this in front of the prime minister, who publicly revealed that she did not seek to add the 600,000 West Bank Arabs to the State of Israel and to change the country’s internal demography. Galili rejected the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel on the West Bank of the Jordan (ISA, 8/7067).

As for Israel’s border with Syria, Galili said that a change to the international boundary was needed. As far as he was concerned, the State of Israel needed to protect its northern territory and would not therefore leave the Golan Heights nor return to the British Mandate border. The settlements in the Golan Heights demonstrated the Israeli government’s intentions regarding the border with Syria in this region. As for Lebanon, Galili presented the Israeli government’s position that it was willing to sign a peace treaty according to the border at that time, as was determined at the end of the War of Independence. In general, Galili’s stance was that all territorial issues and borders should be discussed as part of negotiations with the relevant Arab countries.

The minister mentioned that negotiations must take place without preconditions: “The government of Israel will not give a UN envoy or the Arab countries any prior territorial commitment demanded of it as a condition for negotiations. The government will not demand of the Arab countries to give it any prior commitment on the territorial issue. The borders will be determined by negotiation, by agreement, and not through coercion by other bodies” (ISA, 8/7067). Moreover, the following sections of Galili’s letter state that in order not to hinder the opening of negotiations, the government preferred to refrain from detailing its ultimate demands on the territorial issue. The minister demanded that this be done only under concrete circumstances during negotiations. He also stated that Israel absolutely rejected the understanding of Security Council Resolution 242 as withdrawal from all of the territories to the previous borders, and that Israel’s February 26, 1971 response to UN Ambassador Gunnar Jarring remained in force.[5]

Galili justified his position to the prime minister and said that the government of Israel rejects claims that its policy is one of “expansion” or “annexation.” Israel aspires to defensible borders that require considerable changes to the previous boundaries. According to him, while avoiding the term annexation, Israel should be careful not to mislead others into thinking that it intends to accept the previous borders (neither of the British Mandate nor those that preceded the Six Day War). On the topic of demilitarization of the territories (following border changes) Israel’s position was not that of “mutual demilitarization,” as Israel rejected demilitarization of areas in its territory and rejected the stationing of an “international force” within its borders. According to Galili, Israel was willing to hold negotiations with each of its neighbors separately, and even to sign a separate peace agreement with each of its neighbors (ISA, 8/7067). In Labor Party meetings and in government discussions, this action plan for the territories came up for discussion many times. Many opposed Galili’s proposed plan, and they expressed their concern about determining a position regarding the future of the territories (Bloch 1973).

Moshe Dayan’s Proposal Regarding the Territories

Following the Galili and Allon proposals that were submitted to the government, on August 14, 1973, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan submitted his proposal for addressing the territories, the local population, and the changing demography—“Policy in the Territories in the Next Four Years” (ISA 13/7022, 14/7022). In his proposal, Dayan listed ten demands for advancing the needs of the local population and the settlement concept in the held territories. The first demand was regarding the refugees. Optimal handling of this issue required a budget increase of about 100 million Israeli pounds per year for the existing refugee camps. The second demand discussed the issue of industrial development to foster commerce and the economy in Gaza and the West Bank, and the third focused on urban and industrial centers. Regarding Jerusalem, this meant expanding urban and industrial occupancy to the south, north, and east, beyond the Green Line. The proposal included planning the town of Yamit in the Sinai Peninsula and its expedited development so that it would become a regional urban center for the area south of Gaza known as the Rafah Salient. Dayan elaborated on the need to establish a deep-water port south of Gaza irrespective of the development of the Haifa and Ashdod ports. The settlement of Kiryat Arba was mentioned in the context of the plan to rapidly develop industry and population centers, including establishing an urban settlement in Nebi Samuel. As for the areas where a Palestinian Arab population resided in the towns of Qalqilya and Tulkarm, the need to establish an industrial zone in Kfar Saba was emphasized, for the employment of the entire population of the region—Jewish and Palestinian—and to drive Jewish entrepreneurship of industrial and residential enterprises in the area. The industrial zone was to be established on 1,200 dunams of absentee property.[6] The Golan Heights was also mentioned as a region in which to establish an urban industrial center that would be able to provide employment for all sectors of the population there.

Settlement was the fourth demand in Dayan’s proposal—the establishment of additional Jewish settlements throughout the West Bank, in order to consolidate the Jewish demography there. The fifth was encouraging the establishment of industrial zones with factories in the West Bank. Dayan planned to establish urban settlements that would attract a large population and would become employment and residential centers. The sixth demand discussed rural settlement and the establishment of industrial factories; the seventh discussed the acquisition of land. The Israel Land Administration needed to acquire land in the territories for the purpose of settlement, establishing private and public factories and for the sake of future land exchanges. The acquisition of companies, private lands, and property were considered part of a political and security initiative. The eighth demand in the document discussed the employment of the Palestinian residents of the territories. Their work in the territories was to be monitored and supervised to ensure that their conditions and pay reflected those prevailing inside Israel. The ninth demand referred to relations with Jordan. Dayan believed that Israel should encourage and strengthen the territories’ residents’ ties and connections to the Kingdom of Jordan. The tenth demand stated that it was important to promote local workers in the territories to management positions, including senior positions in the government offices dealing with civil matters. According to Dayan, these positions should be passed on to the local Arabs in order to encourage them to integrate into society and industry and to improve their economic situation (ISA 13/7022, 14/7022; Mileer-Katav 2012; Kipnis 2009, 134-135).

Combining the Dayan and Galili proposals into the “Galili Document”

As mentioned above, both the Galili and Dayan proposals, which were put to vote separately, were rejected by the ministers of the Labor Party. Galili then set about merging the two proposals into a single, organized, binding document. Galili’s suggested merger provoked prolonged discussions in the party over the course of four meetings,[7] at the end of which the final draft of the joint summary was accepted. It addressed the action plan for the held territories, discussed the demographic issue at length, and, among other things, made proposals to address the issue. The final draft of the agreement between the ministers Pinchas Sapir, Moshe Dayan, and Israel Galili was submitted to Prime Minister Meir on August 14, 1973. On September 3, 1973, Galili submitted the draft—“Agreements and Recommendations on an Action Plan for the Next Four Years”—for discussion and government approval, and it was referred to as the Galili Document. The document was discussed twice within the party—first at the beginning of September and again after the Yom Kippur War, on December 5, 1973 (Dayan 1976, 553-560).

The introduction to the proposal stated that the agreement did not reflect party policy of either the Labor Party or the Alignment, but rather recommendations of two Labor Party ministers.[8] The prime minister was mentioned as the person who would bring the agreement forward for approval by the authorized institutions, meaning the party and the government. The agreement expressed the Alignment’s election platform and was included as part of the government’s overall action plan. After receiving government approval for the essence of the plan, operational details were to be outlined, and the implementation budgets were included in the government’s annual budgets. The action plan for the next four years starting in 1973 did not involve changing the political status of the territories and the civil status of the residents and refugees (Mileer-Katav 2012).

The proposal’s principles focused on the demographic aspect of consolidating Jewish settlement in the West Bank on one hand, and addressing the demographic aspects of the local Palestinian population on the other hand. Dayan and Galili’s joint proposal and their individual proposals do not contain a plan for the demographic separation of the Palestinian population from the Israeli settlements that expanded throughout the West Bank and the Jordan Valley. The proposals emphasized large-scale Jewish settlement and creating facts on the ground to maintain claim to and control of the land, while completely ignoring the demographic future of the territories in the coming decades. The plan’s main focus, as detailed below, was to consolidate Israeli control of the territories while considering the civil needs of the local residents. As government representatives, their document was supposed to set out guidelines for administering and managing the local Palestinian population, but this was also rejected by the government.

15 principles were included in the joint proposal: the first addressed the responsibility of the incoming government. The document stated that the next government should continue to operate in the territories based on the policies pursued by the current government, with an emphasis on the local population. These encompass development of the territories in terms of housing, transportation, agriculture, employment and services; economic relations, open bridges, autonomous activity and the renewal of municipal representation, decrees by the military governorate, rural and urban settlement, rehabilitating the refugee camps, and monitored and regulated employment for the territories’ Arab residents in Israel. The second principle focused on the Gaza Strip. The document stated that an emphasis would be placed on rehabilitating refugees and developing the Gaza Strip for the purposes of residence, agriculture, and industry for the benefit of the local residents. In addition, a four-year action plan was proposed, with allocations for the necessary funding for its implementation. The main aspects of the action plan focused on improving the condition of the local residents in the held territories with an emphasis on housing conditions, that is, establishing residential neighborhoods for the refugees next to the camps, rehabilitating the camps and including them in the municipal responsibility of the adjacent towns. Other areas included professional training, advancing health and education services, creating sources of livelihood in crafts and industry, and encouraging the individual initiative of residents to raise their standard of living.

The third principle in the document related to developing infrastructure in the West Bank. The proposal included a four-year action plan that would ensure the necessary funding for developing the economic infrastructure and advancing essential services, such as health and education, improving the water system according to the needs of the population, advancing professional and post-secondary education, improving electricity and contact services—meaning communication and transportation—, renovating roads and access routes, developing crafts and industry as sources of employment for residents, improving housing for the refugees, and assistance for the municipal authorities. The fourth principle in the document presents the understanding that was reached between the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Defense, concerning funding for the action plans in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. It noted that efforts would be made to attain economic means from foreign sources to fund the rehabilitation of refugees and to develop the territories.

The sixth principle in the document stated that concessions and benefits would be offered to encourage Israeli entrepreneurs to invest in establishing industrial factories in the territories (according to the Minister of Trade and Industry’s proposal to the Ministerial Committee on Economic Affairs from August 1, 1973). The seventh principle addressed the autonomous activity of West Bank residents in which they would advance and develop business, agricultural, and economic initiatives in their areas of residence in the held territories. The eighth principle discussed the provision of aid to support the population’s autonomous activity in the areas of education, religion, and services, and the cultivation of democratic values and practices in social and municipal life. The goal was to encourage the local residents to fill senior civil positions in the machinery of local government, in order to integrate them in the day-to-day administration. It also stated that the open bridge policy between the two sides of the Jordan river would continue, to allow trade to continue as before. The ninth principle specified the integration of residents of the territories in various kinds of work inside the State of Israel. It stated that such residents’ work in Israel and in Jewish enterprises in the territories would be numerically and regionally controlled, and measures would be enacted to ensure comparable pay and working conditions to those prevalent in Israel (Pattir 1973).

The tenth principle advocated for the establishment of new settlements and the strengthening of the settlement system. The government of Israel was to encourage Jewish settlement in the West Bank by developing crafts, industry, and tourism catering. When setting the government’s budgets, the necessary funds for new settlements would be determined each year, according to the settlement department’s recommendations and approval of the ministerial committee on settlement. The aim over the subsequent four years was to establish additional settlements in the Rafah Salient, in the Jordan Valley, and in the Golan Heights; an industrial urban settlement in the Golan Heights, and a regional center in the Jordan Valley; to develop the northeast of the Sea of Galilee and the northwest of the Dead Sea, and to establish the planned water works. Public and private non-governmental bodies were to join forces in the regional development of settlement in the territories as part of the approved plans. As for the regional center near Rafah Salient, it was to encompass 800 housing units by 1977-1978 and industrial development and settlers willing to settle there through private means would be encouraged. The eleventh principle focused on acquiring and zoning land in the territories. The document states that efforts to designate lands for the needs of existing and planned settlement were to increase (including acquisitions, government lands, absentee lands, land exchanges, and agreements with residents). It also stated that the Israel Land Administration would operate to increase the acquisition of land and properties in the territories for the needs of settlement, land development, and land exchanges. And that it would lease land to companies and individuals for the purpose of implementing approved development plans. The Administration would also act to acquire land in any effective way, including through companies and individuals, in coordination with and on behalf of the administration. Companies and individuals would be permitted to acquire lands and properties only in cases in which it was clear that the administration could not acquire the land and be its owner, or was not interested in doing so. The twelfth principle states that the body authorized to provide these approvals would be the ministerial committee. Approvals would be provided on the condition that the acquisitions were intended for constructive enterprises and not for speculation, and not as part of the government’s policy. The Israel Lands Administration would also act to acquire and be the owner of lands acquired by Jews.

The thirteenth principle mentioned in the document concerned Jerusalem and its surroundings. It declared the state’s intention to populate and industrially develop the capital and its surroundings with the purpose of consolidation beyond the more immediate area addressed by Decree No. 1 (IDF Archives, 117/1970).[9] To this end, an effort would be made to acquire more land, and those state lands east and south of Jerusalem that the government had closed, would be utilized. The fourteenth principle states that the government decision from September 13, 1970 on the settlement of Nebi Samuel should be implemented. With respect to a port south of Gaza, it stated that following the expedited development of the Rafah Salient, within two or three years the basic data of the proposal to establish a deep-water seaport south of Gaza would be examined, including physical aspects, economic feasibility, and political considerations. After the compilation of the findings and the submission of a concrete plan, the government would decide on the issue. The fifteenth principle in the document is the establishment of an industrial center for Kfar Saba and its surrounding area beyond the Green Line, and the development of Israeli industry in the areas of Qalqilya and Tulkarm.

The text of Dayan and Galili’s proposal presents the complexity of the demographic dimension as expressed in Jewish settlement in the West Bank vis-à-vis the existing Palestinian population there. The document’s principles lay out the government demands for the consolidation of Jewish settlement in order to create territorial contiguity that would ensure Israel’s hold on the land and encourage private Jewish investment in developing the territory. On the other hand, there was an intention to find practical solutions for the local population in order to enable them to earn a living and develop industry, practice agriculture, pursue an education, maintain a connection with the East Bank, and travel between the two banks, as well as throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The demographic changes created by the incoming local Arab population forced the government to find immediate solutions and formulate a long-term plan for future implementation. Meanwhile, the government’s decision to urgently establish Jewish settlements is the result of the need to create a Jewish demographic reality on the ground.

King Hussein’s Federation Plan

The fourth proposal came from the East side of the river, from the palace of King Hussein of Jordan. It is different from the previous proposals in three important ways—first in originating in an Arab country and at the initiative of King Hussein. Second, the proposal revealed the king’s aspiration to maintain the continuity of his rule and his patronage of the Palestinian population in the West Bank. Third, it is a kind of “mirror proposal” in contrast with the considerations behind the three Israeli proposals. The essence of the proposal was to maintain Jordanian territorial contiguity in the West Bank and administrative hegemony over the territory and to preserve Jordanian rather than Israeli patronage of the population . Hussein rejected Allon’s proposal and believed that his proposal would be acceptable to the local Arab residents and to the Israeli government. On March 15, 1972, Radio Jordan broadcast King Hussein’s plan to reorganize the Hashemite monarchy and render it the united Arab monarchy. At the center of the proposal were several principles. First, it proposed a common point of reference for the Palestinians, especially the local residents in the West Bank, which would maintain Palestinian identity in the framework of an Arab country and demographic continuity with the Kingdom of Jordan. It seems that the king believed that the residents would prefer to live in an autonomous federal Arab regime rather than under Israeli rule. Second, Hussein sought to represent the Palestinians, rather than the militant voices of the fedayeen leaders in the West Bank, who had formerly attempted to oppose his rule. Third, the king sought to strive for a solution to the question of the West Bank in a way that would return the territory to him, thus ensuring the return of the land to the members of his people and rule over Jerusalem and the holy places in it. Fourth, Hussein believed that this action would present him as an Arab leader of stature in the eyes of the moderate Arab community. In this way he hoped to regain the faith of the Arab countries in him and economic support for Jordan, which suffered following his suppression of the sabotage operations of the terrorist organizations in the kingdom. Hussein saw the plan as an opportunity to maintain Arab demographic unity on both sides of the Jordan and his standing as the only leader of the territory.

The plan suggested the creation of two main autonomous provinces: Palestine and Jordan. According to the plan, these provinces were to operate as a federation under a central government with a national assembly located in Amman. Amman would be the capital of the Jordanian provinces and Jerusalem would be the capital of the Palestinian provinces, and each province would have a governor general for internal administration, a government, and a council elected by the people. The government in Jordan was to be the supreme authority on foreign relations and security, and there would be one central army headed by the king. The main judicial branch would be under the authority of the central supreme court, though there would be an independent authority in each province. The plan does not relate to the Jewish settlements that proliferated in the West Bank and the Jordan Valley, nor to the presence of Israeli military and security forces in the territory by virtue of this. In addition, the plan lacks a strategy or political intention for negotiations with Israel, including peace. The king prepared the plan covertly and did not share it with Israel or the United States or even with other Arab countries. When Hussein announced it, the responses were not long in coming, and he was thoroughly denounced by all sides. Israel flatly refused to give up the territories in the West Bank and Jerusalem, and did not agree to Jordanian administrative intervention in its territories.

The day after Hussein’s announcement, on March 16, 1972, Golda Meir gave a scathing speech in the Knesset. She said that the king was purporting to administer a territory that was no longer in his possession, and if he wished to reach any agreements, he must do so with her through negotiations. Meir attacked the king’s plan because it did not mention the term peace even once and was not based on an agreement. She was furious “about the king’s presumptuousness in defining Jerusalem—Israel’s eternal capital—as the capital of Palestine (ISA, 6/7033). The rest of the Arab countries believed that the plan was impossible, as the territory was under Israeli military control. Palestinian protest movements even called Hussein a traitor for having spoken in their name and having tried to “sell” them to the Israelis. The Council of the Presidency of the Arab Federation, which was held in Cairo from March 11 to 14, 1971, published a condemnation of King Hussein’s unilateral declaration and said that it was a plot against the Arab nation. U.S. Secretary of State, Williams Rogers made clear to the king that the United States would not take a public stance with respect to his plan because it sees it as an internal Jordanian matter, while Egyptian President Anwar Sadat severed diplomatic relations with Jordan in response to Hussein’s declaration (Elpeleg, 1977; ISA 6/7033, 10/7245).

For 21 years King Hussein tried to return the territories of the West Bank and their residents to his kingdom. The king saw the loss of Jerusalem and the West Bank and their Arab population to Israel as an artificial demographic division. According to his shelved plan, the Kingdom of Jordan was to rule the territory and its Arab population in order to give full expression to Arab hegemony there, but when he did not succeed in fulfilling his intentions, he felt betrayed and abandoned by the members of his nation. Observing the fast Israeli construction and settlement throughout the West Bank, Hussein came to understand that the situation could not be undone, and expressed his bitter disappointment in the Palestinian uprising that led the public to support the PLO (IDFA, 021/843). In July 1988 the king announced a unilateral separation from the West Bank and declared that while Jordan was detaching itself from the West Bank, it would always be committed to the Palestinian people and the Palestinian struggle, and that he was turning towards regional peace. (Nevo, 2005).

Comparison of the Proposals to Administer the West Bank, 1967-1977

The four proposals presented different ways of administering and addressing the West Bank territories. Each proposal represents the opinion and stance of its initiator: Yigal Allon, Israel Galili, Moshe Dayan, and King Hussein. Compiling the data from the four proposals in one table reveals their similarities and differences The table shows the government response to each of the proposals: rejection.

| Who submitted the proposal: | Yigal Allon | Israel Galili | Moshe Dayan | King Hussein |

| Israeli | Israeli | Israeli | Jordanian | |

| Date of submission | June 26, 1967 | March 27, 1972 | August 14, 1973 | March 15, 1972 |

| Official name | The Future of the Territories and Treatment of Refugees | Handling the New Territories Added to the State of Israel | Agreements and Recommendations on the Action Plan for the Next Four Years | The Unified Arab Kingdom of Jordan |

| Informal name

| The Allon Plan | The Galili Document | Policy in the Territories in the Next Four Years | The Federation Plan |

| Submitted to: | Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir | Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir | Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir | The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the public |

| Presented in: | Labor Party conventions | Labor Party meetings and government meetings | Labor Party meetings and government meetings | Radio Jordan |

| Number of drafts | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Submission dates of the additional drafts | February 27, 1968 December 10, 1968 January 29, 1969 September 23, 1970 July 17, 1972 | September 3, 1973, joint proposal with Dayan | September 3, 1973, joint proposal with Galili | |

| Control of the West Bank | Territorial compromise: Israeli control of security areas; Arab control of areas with Arab population centers | Israeli control | Israeli control | Full Jordanian control |

| Control of Jerusalem | Full Israeli control | Israeli | Israeli | Capital of the Palestinian provinces under Jordanian control |

| Employment of local Arab residents | Yes, only in their places of residence | Yes, also in Jewish industrial zones and integrating them into the Israeli economy | Yes, also in Jewish industrial zones and integrating them in the Israeli economy | Yes |

| Demographic dimension: settlement of local Arab residents | Yes, in concentrations of Arab settlement | Yes, in concentrations of Arab settlement | Yes, in concentrations of Arab settlement | Yes |

| Demographic dimension: Jewish settlement | Yes, in the Jordan valley and on the mountain ridge | Yes, throughout the West Bank | Yes, throughout the West Bank | No |

| Demographic dimension: calculations of future population | None | None | None | None |

| Borders | Israeli control of the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge with the Jordan River as the eastern border. Areas populated with Palestinian residents to remain under Palestinian control. Corridor at Jericho for the Arab population’s passage to Jordan | The Jordan River | The Jordan River | The entire West Bank as an autonomous province |

| Administrative control / sovereignty | The mountain ridge + Jordan Valley + Jerusalem under Israeli control. Concentrations of Palestinian settlements in the West Bank under Arab control. | Israeli | Israeli | Jordanian federal control |

| Outcome of the proposal | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected |

Discussion: Comparative Analysis of the Proposals, With an Emphasis on the Israeli Proposals

The similarities between the three Israeli proposals rest on three main motives: security, demography, and economy. In all three proposals the issue of security is the foundation for future thinking about control of the West Bank territories, with an emphasis on defensible borders and control of the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge for the sake of control over the region and strategic maneuvering. Moreover, in all three proposals, Jerusalem is the capital of Israel under Israeli sovereignty and the Jordan River is the eastern border of the State of Israel. The demographic motive in the three proposals strengthens the Zionist vision of Jewish settlement in the Jordan Valley combined with agricultural work there, while creating territorial contiguity between all parts of the land. In addition, all of the proposals lack a future calculation of the dimensions of demographic growth among the local Arab and Jewish population. The economic motive encourages the integration of the population of local Arab residents into employment in Israeli factories throughout the West Bank and even within the State of Israel. The authors of these proposals were motivated on the one hand by the importance of developing the independence of the local residents in local employment, and to help them advance agriculture, commerce, and industry for the benefit of their continued livelihood. On the other hand, the residents of the West Bank were seen as cheap labor for Israeli industry. The authors believed that employment in the Israeli market would lead to an increase in the income of local Arab residents and thereby also their quality of life and economic welfare.

The differences between the three proposals also relate to the three main motives: security, demography, and economy. The discrepancies are evident mainly between Allon’s proposal and those of Galili and Dayan. Allon submitted his proposal six times on various dates between 1967 and 1973. Galili’s proposal was submitted once on March 27, 1972, and Dayan’s proposal was also submitted once, on August 14, 1973. The latter two were ultimately unified into a joint proposal that was submitted under the title “The Galili document” on September 3, 1973. On the security issue, Allon proposed a territorial compromise that included a separation of areas under sovereign Israeli control and areas with concentrations of local Arab population. In Allon’s opinion, Israel needed to establish Jewish settlements in the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge, in order to strengthen these areas and to ensure a strategic Israeli hold there. Regarding the areas settled by locals, Allon proposed that they would continue to administer their lives there autonomously, and Israel would also create a corridor to Jordan for them—the Jericho corridor. Allon saw territorial compromise and separation of the different populations as a solution, and in the name of the settlement vision, proposed the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge as extensive areas for settlement and agriculture. In contrast, Galili and Dayan’s proposal did not allow local residents to have autonomous control of areas with concentrations of Arab population; rather, they saw all areas of the West Bank as areas in which to apply Israeli control and sovereignty.

The demographic issue in Allon’s proposal relates to Jewish settlement only on the mountain ridge and in the Jordan Valley, and to providing administrative and settlement autonomy to the local Arab residents in their existing concentrations of settlement. This differentiates Allon’s proposal from the other proposals in the demographic dimension. Allon saw a need to separate the populations by means of clear borders, while allocating territories for Jewish settlement in areas in which no local Arab population was settled. While his proposal lacks a future demographic calculation of the growth of the Jewish and Arab population, he apparently understood that natural demographic growth would lead to conflicts over borders. According to Galili and Dayan’s proposal, both of them saw Jewish settlement throughout the West Bank as an immediate need, in order to create a settlement reality on the ground and territorial contiguity. The economic aspect in Allon’s proposal concerns the need for separation between Israel’s territories and the territories of the local residents. Allon argued that there should be a separate economy and separate employment, but with collaborations. In contrast, in Galili and Dayan’s proposal it seems that there is an intention to encourage local employment but also a desire to integrate them into employment in the Israeli market, based on the authors’ view that employing the locals as cheap labor would benefit the Israeli economy and also improve their quality of life.

An examination of the implications shows that the three Israeli proposals attribute great importance to the issue of security and Jewish settlement in the West Bank territories, with an emphasis on the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge. The three proposals emphasize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel under Israeli sovereignty and the Jordan River as the eastern border. If these erudite proposals are the product of the serious thought of such veteran ministers in the government of Israel as Allon, Galili, and Dayan, who saw the strategic and security issue as an essential guideline for the continued existence of the State of Israel and presented them to the Labor Party and Prime Minister Meir based on their best judgement and consideration, then this raises a question: Why did the governments of Israel refrain from officially adopting one, all, or some aspects of the proposals?

After an in-depth examination of the various proposals, I believe that the government of Israel was blinded by the extensive territory of the West Bank that was conquered in the Six Day War, faced constant military tension, and decided not to decide. Postponing a decisive decision on the future of the territories and their Palestinian population met the needs of Israel’s governments from 1967 to 1977. The governments that served during this decade faced three wars and preferred to focus on what they had and not on what they had to give up.[10] Israel’s governments were preoccupied by the military tension and they preferred to retain territory and control it militarily rather than any other proposed alternative. In practice, the policy was to unify Jerusalem and to apply Israeli sovereignty there, and to settle the mountain ridge and the Jordan Valley to provide strategic depth and as an agricultural settlement area. The government also began to establish Jewish settlements throughout the West Bank in order to create demographic and military-strategic territorial contiguity. Economically, Israel encouraged local Arab employment and industrial development to improve livelihoods, and also promoted the integration of Arab workers in the Israeli market as cheap labor to nurture the Israeli economy. In practice, the government of Israel selectively implemented aspects of the three Israeli proposals, without adopting them. The postponement of a decision on the future of the territories and their population since 1967 has continued to the present time and passes from one government to the next.

Conclusion

Three proposals by Israeli government ministers on the demographic, military, and economic administration of the West Bank territories were submitted to the government in the decade after the Six Day War, but none of them was fully implemented. A fourth proposal came from the palace of King Hussein of Jordan, who proposed to administer the two banks of the Jordan and their Arab population by means of a federal administration under the auspices of the Kingdom of Jordan. His proposal was rejected outright because the government demanded that decisions be made through negotiations and mutual dialogue between the two countries, and not as a unilateral act by the king. One main reason for the rejection of the king’s proposal was that it did not discuss the possibility of peace or negotiations towards peace agreements, and because it stated that the capital of the federation would be Jerusalem, something that Israel saw as impossible. Also, the federation plan gave no expression to the complex local Arab and Jewish demographic reality that had existed for some time in the West Bank and Jerusalem.

But the proposals of Allon, Galili, and Dayan were also not implemented in full. The government chose to adopt only some of the work methods of parts of the plans, according to considerations of time and place. The territory’s artificial division according to demography and settlement areas forced the government to make operative decisions for which the sides were not yet ready to tackle politically. The government of Israel saw holding onto the West Bank as a commitment to preserve the security of the country’s borders and as a basis for any possible future negotiations. The demographic dimension was and remains the heart of the geopolitical conflict on the ground and yet the Six Day War and its predecessors and successors proved again and again that Israel must hold on to the West Bank for strategic depth.

Settling the territory with Jewish population immediately after the war was a kind of national mission and vision. The territories of the West Bank and the Jordan Valley expanded the narrow coastal plain, which was all Israel had until the war, and the determination of the border line itself stemmed from a vision of settling the Land of Israel. The essence of the vision was consolidating Jewish settlement in the area of the mountain ridge and the Jordan Valley, creating a demographic reality of Jewish control of the territory, and unifying the Land of Israel as a single unit. The government gave many grants and royalties to the new settlers and ensured the cultivation of agricultural farms along the entire length of the eastern border line in the Jordan Valley. Meanwhile, the government also started to give expression to the demographic change that had begun in the held territories due to the growth of the local population, and attended to its needs in terms of building infrastructure for transportation, education, employment, and agriculture.

Israel’s decision-makers from 1967 to 1977 were not ready for far-reaching changes in the form of handing over territories to enemy countries and giving up control of the land, which they saw as giving up on security and at that time was certainly too early to consider. The Allon Plan foresaw what was going to happen in the future, in terms of the natural increase of the population—both Palestinian and Jewish—throughout the West Bank. What was innovative about Yigal Allon’s proposal was the demographic separation that would ensure autonomous existence for the Palestinians, and settlement and land control in the Jordan Valley and the mountain ridge for Israel, such that demographic separation would be maintained. In his vision, Allon foresaw what we know became the reality—Jewish settlement alongside Palestinian settlement throughout the West Bank, and a demographic problem that requires decisive and far-reaching decisions.

With respect to the research question—did the governments of Israel during the first decade after the Six Day War formulate a policy on the borders of the country and the population that would be included in it—the answer is that the governments of Israel did not produce any plan to address the demographic dimension, because they were preoccupied by strategic and military matters. In addition, no forward-looking plan was submitted to the government that related to the consequences of the demographic dimension in the West Bank. In practice, the governments of Israel implemented various parts of the proposals, as reality dictated the need. There was no organized action plan for addressing the demographic dimension, and the only principle that guided decision-makers in Israel was creating territorial contiguity of Jewish settlement throughout the West Bank, in order to ensure a border line made of a Jewish “human shield” adjacent to local Arab settlements.

Six decades after the Six Day War, the West Bank and its Palestinian and Jewish populations is still on the political agenda in Israel. While the proposals of Yigal Allon, Israel Galili, Moshe Dayan, and King Hussein belong to the past, various approaches from these proposals were already operating in the first decade after the war, as described. For example, Allon’s proposal to separate between the Palestinian and Jewish populations and to create a buffer between the two nations, to allow passage via the Jericho corridor to Jordan, and a separate and independent existence within the West Bank and the Jordan Valley along with encouraging Jewish settlement there. Surveys of the Israeli and Palestinian Authority central bureaus of statistics describe the large-scale population growth since 1967. Looking to the future, by 2050 the forecast is for significant further growth, reaching about five million Palestinians in the West Bank. Some aspects of the proposals from the ‘70s are also implemented today in some way—for example, the Oslo Accords, the employment of Palestinians in Israel, agricultural collaborations—and the proposals created a conceptual basis for new plans. In the face of future demographic forecasts and in learning from the lessons of Israel’s wars in the past and present, the State of Israel will need to address the burning demographic question of millions of Palestinians throughout the West Bank, and make firm decisions that will ensure its independence as a Jewish and democratic country.

Sources

Israel State Archives (ISA)

File 10/7032 א, 1971: “The Refugees, Draft B.”

File 16/7309 א, 1968: “Held Territories General”; “Economic Development, Held Territories.”

File 18/7309 א, 1973: “Controlled Entry and Residence of Civilians in the Agricultural Settlement Areas in the Territories,” September 3, 1973.

File 20/7309 א, 1968: “Protocols of Labor Party Meetings,” “The Refugees, Draft B.”

File 8/7067 א, 1972, “Minister Israel Galili to Ms. Golda Meir, Prime Minister, Jerusalem,” February 27, 1972.

File 13/7022 א, 1968-1971, “Protocols of Labor Party Meetings.”

File 14/7022 א, 1968-1971, “Protocols of Labor Party Meetings.”

File 6/7033, א, “Prime Minister’s Announcement at the Knesset”; “Talks with Jordan,” March 16, 1972; “King Hussein’s Speech on Radio Jordan on the Federation Plan,” March 15, 1971; “Jordan—King Hussein’s announcement,” March 15, 1972; “Plan to Establish the United Arab Monarchy,” March 15, 1972; “Prime Minister’s Announcement at the Knesset on the Day,” March 16, 1972; “Hussein Plan,” March 1972; “Federation/Announcement of the Council of the Presidency of the Federation Regarding the Hussein Plan,” March 18, 1972.

File 7/2608 א, 1967, “5727 Census.”

File 3/12055 גל, “September 1967 Census.”

File 10/7245 א, “UN General Assembly, ‘Peace Plan with Jordan,’” January 10, 1969; “Jordan—Al Nahar’s interview of King Hussein,” April 4, 1972; “Hussein’s visit,” April 7, 1972.

File חצ-5251/10, Office of Minister Abba Eban, Jordan, “Main points from King Hussein’s speech,” December 1974.

Yad Tabenkin Archives

Division 15 Allon, Container 4, File 5, “Allon Plan Questions and Answers,” Al Hamishmar, December 2, 1977.

Division 41, Container 9, File 5, “Allon Plan,” 1968; “Israel-Jordan talks, Meir-Hussein, 1971-1972.”

Division 8-15, Container VII, File 31772, “Allon Plan, to Clarify the Plan and its Essence.”

Division 41, Container 9, File 5, “Allon Plan – Symposium,” June 27, 1990; “To the Government Secretary from Yigal Allon.”

Division 15, Container 4, File 5, 1968; “About the Allon Plan,” interview with Minister Yigal Allon: Yigal Allon, Questions and Answers," Al Hamishmar, December 2, 1977.

IDF and Defense Establishment Archives (IDFA)

File 117/1970, “Proclamations Published by the IDF by the Commander of the Forces in the Area.”

File 021/843, “Daily Collection of Information as of May 20, 1988.”

Literature

Elpeleg, Zvi. 1977. Hussein’s Federation Plan: Factors and Responses. Shiloah Institute, Tel Aviv University.

Bloch, Daniel. August 19, 1973. “The Galili Document and the Allon Plan.” Davar.

Brown, Aryeh. 1997. Personal Stamp: Moshe Dayan in the Six Day War and After. Yedioth Ahronoth.

Gazit, Shlomo. 1985. The Stick and the Carrot: The Israeli Administration in Judea and Samaria. Zmora-Bitan.

Dayan, Moshe. 1976. Milestones: Autobiography. Yedioth Ahronoth.

Zak, Moshe. 1996. Hussein Makes Peace: Thirty Years and One More Year on the Path to Peace. Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies.

Traube, Ronen. 2017. “Yigal Allon and the Palestinian Issue: From Denial to Recognition.” In Israel 1967-1977: Continuity and Change, Studies in the Rebirth of Israel, Volume 11, edited by Aviva Halamish and Ofer Shiff, 407-431. Ben-Gurion Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism.

Miller-Katav, Orit. 2012. Relations Between Israel, Jordan, and the United States During the Establishment of the Military Governorate in the West Bank, 1967-1974. [PhD thesis, Bar-Ilan University.]

Nevo, Yosef. 2005. Jordan: The Search for Identity. The Open University.

Pattir, Dan. August 16, 1973. “The Full Text of the Agreement of the Labor Ministers on the Action Plan in the Territories.” Davar. http://tinyurl.com/5nzsn7fp

Kipnis, Yigal. 2009. The Mountain that was Like a Monster: The Golan between Syria and Israel. Magnes.

Ramon, Amnon and Yael Ronen. 2017. Residents, Not Citizens: Israel and the Arabs of East Jerusalem, 1967-2017. Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research.

Further Reading

Israel State Archives (ISA)

File 4/4327 א, Australia New Zealand, “The Jordan is Palestine Committee,” September 17, 1981.

File חצ – 7015/14, Office of the Director-General—Territories Forum, “Jordan task force—territories,” November 8, 1988.

Minutes of Government Meeting 74, 26th of Elul 5727, October 1, 1967.

Yad Tabenkin Archives

Division 15 Allon מ/ה, Container 18, File 1, September 23, 1970; “Personal—for Publication, Receipt of Letter.”

Division 15 – Allon, Container 19, File 7, October 4, 1968, October 10, 1968; “To Yigal Allon, Deputy Prime Minister, Prime Minister’s Office”; “Allon Plan, Outline for Lecture, Yigal Allon.”

112/6 א, 1971-2; “Letters and Summaries of Government Meetings and PM Meeting with U.S. Representatives.” 71141/ א, 1968-1971.

Division 45, Container 48, File 1, September 22, 1972.

IDF and Defense Establishment Archives (IDFA)

File 004/843, “Daily Collection of Information as of December 30, 1988”; “Daily Collection of Information as of July 31, 1988”; “Daily Collection of Information as of August 1, 1988”; “Daily Collection of Information as of August 2, 1988”; "”Daily Collection of Information as of August 4, 1988”; “Daily Collection of Information as of August 5, 1988”; “Daily Collection of Information as of August 7, 1988”; "Daily Collection of Information as of August 8, 1988”; “Daily Collection of Information as of September 14, 1988”; “Daily Collection of Information as of August 16, 1988.”

File 024/843, “Daily collection of Information as of April 21, 1988”; “Daily Collection of Information as of September 30, 1988.

U.S.A. National State Archives

RG, 59 General Records of the Department of State, Central Foreign Policy Files 1967–1969, Political and Defense, POL 7 Israel to POL 12 ISR, Box 2225.

“Israeli Request for MRS. Meir Visit to Washington and Replay her Letter to President,” May 21, 1969.

“Israeli Deputy Prime Minister visits Denmark,” September 24, 1969; “Alon’s Visit,” September 10, 1968.

“Appointment with Israeli Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Alon,” August 20, 1968.