Strategic Assessment

This article—which was written prior to the onset of the Swords of Iron War in October 2023—reviews current and expected demographic developments in the State of Israel up to 2050, together with a broad look at the Jewish Diaspora, based on assumptions which will be described in the article. The underlying theory is that the Israeli population is not a closed system but rather draws its human resources from the Jewish communities around the world and from Middle East populations. Israel in turn, is a source of human and other substantial resources for these populations. A central question the article will examine is that of the balance between Jews and Arabs within a geopolitical entity that is supposed to fulfil two conditions—that of a Jewish and a democratic state—in the space between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. Another weighty question relates to the internal balance between the various segments of the Jewish population within the Israeli state, including their degree of affinity to religion and religiosity. A third question relates to the reciprocal relations between the core Jewish-Israeli state and the Jewish Diaspora around the world in the long term. Based on data from population surveys and demographic forecasts, I will explore a number of implications, which should be at the center of any strategic assessment in the State of Israel in the coming decades.

Key words: Israel, the Palestinian Authority, population, demography, migration, natural growth, Jewish identity, Diaspora Jews, Jews, Arabs, Haredi (very orthodox), forecasts

The Predictive Value of Forecasts

The French author and artist Jacques Prévert (Prévert 1951) dedicated one of his famous songs to man’s ability to predict history. He listed a few dates of important junctures in the history of France and asked ironically who, including the most wise and professional observers, could have predicted what actually took place on those dates?

To borrow this method for important years in the history of Israel in the modern era, who in 1897 could have predicted 1939? Who in 1939 could have predicted 1945? Who in 1945 could have predicted 1948? Who in 1948 could have predicted 1967? Who in 1967 could have predicted 1991? Who in 1991 could have predicted 2022? And who in Israel, on November 1, 2022, could have predicted what took place on October 7, 2023? These dates represent a collection of critical turning points in Jewish and Israeli history over the past 125 years, more or less. From the first Zionist Congress in Basel to the outbreak of the Second World War, via the Holocaust and the declaration of an independent State of Israel, the Six Day War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, or the attempted legal-regime reform in Israel and the public’s response, as well as the still-unknown consequences of the Swords of Iron War. Anyone in 2024 who seeks to predict 2048, which will be the 100th anniversary of Israel’s existence, or 2050, will not have much more success. As of the writing of these lines, the future appears more unknown and unpredictable than ever before.

The Mishna states: “Everything is foreseen yet freedom of choice is granted” (Pirkei Avot 3:15). This may not be an optimal formula for contemporary social science, but the fatalist approach that says nothing can be forecast and everything is unexpected is also unacceptable. Indeed there appear to be a number of core elements that have characterized Jewish experience over the past century—including on the social demographic front—that are still at work today and will most likely continue to be relevant in the foreseeable future. These may serve as an overall conceptual framework, or as a compass to navigate in three contexts: the Jewish-Arab equilibrium, the balance amongst Jews with varying degrees of religious identity in Israel, and Israel-Diaspora relations (DellaPergola 2022a).

This article will briefly review a selection of central demographic trends that influence these core issues, in Israel and the Jewish world, and suggest potential scenarios for expected developments and their consequences for the future existence and character of the State of Israel. It will also suggest that increased attention should be paid to these subjects; they are presently almost entirely absent from governing authorities’ strategic planning and thought.

A Challenging Road Ahead

The State of Israel was created for one central purpose: to fulfill the right of the Jewish people to a sovereign state in their homeland. The country which was recognized by the General Assembly of the United Nations on November 29, 1947, as the “Jewish state,” and whose independence was declared in a speech by David Ben Gurion on May 14, 1948, is the State of Israel. The equal rights promised to all citizens in the Declaration of Independence, regardless of personal identity, emphasized the Jewish and democratic character of the new state. Today, 75 years later, the demographic challenges to Israel’s existence as a Jewish and democratic state can be arranged in four overlapping categories:

- The identity of the State of Israel in relation to other hostile national and religious identities and realities in its close geopolitical environs. The results of the unsolved conflict with the Palestinians will determine the identity of Israel, the setting of permanent territorial borders for the state, the profile of the population included within those borders and the nature of reciprocal relations with neighboring states.

- The identity of the State of Israel in relation to the national identities and aspirations of the non-Jewish citizens living within it. The definition of Israel as a Jewish state (or as the state of the Jews) depends on the ethnoreligious demographic balance within the state’s borders, while maintaining its demographic character and the individual rights of all its residents.

- The identity of the State of Israel in relation to the variety of Jewish communities spread across the world. In order to ensure the relevant foundation of Israel as the Jewish state it must maintain a coherent balance between competing religious and cultural Jewish components domestically, and develop mutual, agreed upon reciprocal relations with the Jewish people internationally. This requires significant legal, cultural and socio-economic processes within the state.

- The quality of life in the State of Israel for its residents, according to general criteria of ecological and economic sustainability. The size and composition of Israel’s population, its geographic dispersion and density, socioeconomic and infrastructure development and the relations of all of the above to the physical environment will definitively influence the quality of life in the state and people’s willingness to live in it.

There are numerous challenges to a contemporary investigation of Israel and the Jews’ demographic future. Observers of the present need to be completely aware of the idiosyncratic character of some of the most tragic and the most uplifting developments in all of Jewish history, and of the consequences of political processes taking place before our eyes. It is also clear that most of what we know and what is taking place at the time of writing is the result of extraordinary, unexpected and sometimes disruptive circumstances, and not the result of orderly, planned and linear developments in Jewish chronology.

Nevertheless, taking into account a measure of uncertainty, from the point of view of the empirical branches of the social sciences, certain types of future events may be anticipated and even predicted with a fair degree of accuracy. The common terms of “optimism” and “pessimism” are foreign to such a rational framework. The demographer relies on a small number of components that determine population changes, whose patterns are known in advance, which were chosen for a given simulation of potential outcomes. The analytic roots of any attempt to clarify what the future holds rely on a careful examination of evidence and indications from the past and the present. Following attempts to derive insights into how the motives and results of major processes worked in the past, we apply those insights to understand the chances that the future will see continuity or discontinuity in the trends observed. Beyond the theoretical impact, what occurred may help us expose what we will call “the inherent logic of the system.”

Of course, neither in the Jewish or any other experience, does the past determine the future. When forecasting expected population changes, as in any other field, there are no easy deterministic solutions. In demographic terms the implications of a given feedback in the making, even if it is marginal or latent, may be a leading factor in the next stage. It is not only the weight of the different components within a given model that may change over time. The logic of the entire system may shift due to internal changes created in the wake of prolonged variations in the structure and even the nature of the collective. Sometimes a relatively marginal change may affect the balance of the entire system, in what is known as a tipping point (Gladwell 2000). This concept does not refer to the transition from, for example, 50.1% to 49.9% in Israel’s Jewish or non-Jewish population, but rather to the point beyond which a given situation is no longer possible—for example that the state will be both Jewish and democratic—and this may be an entirely different ratio. To illustrate on a much smaller scale: a Jewish day school in the diaspora, from kindergarten through the age of matriculation exams, is feasible in a local Jewish community of at least 4,000 Jews, but is essentially unfeasible in a community of 2,000. The implications for local Jewish identity, of this modest quantitative gap, in a situation where there is or isn’t a certain communal institution or service, may be significant. Such a threshold of possibility or tipping point, is especially sensitive to the framework of local social and demographic forces, but also depends on national, regional and global developments.

The Jews in Israel and Around the World—Trends and Developments

The point of departure for assessing the future of the State of Israel and the Jewish people, entails a maximally accurate outline of the current profile of the worldwide Jewish collective and of demographic trends that affect it. To this end, large amounts of raw data—usually of unequal quality—must be collected, evaluated and adjusted, in order to fully and reliably map the current situation and to support comparisons as far as possible (DellaPergola 2023). The current situation is a result of both short term changes that have taken place before our eyes over a brief time span, and deeper transformations that reflect prolonged and convoluted historical trends. Furthermore, it is legitimate to compare the actual situation to what can be defined as the preferred option or even a utopian dream, and to recognize the existence of a few competing ideal models.

The Logic of the Global Geographic System

From a historic-geographic viewpoint, the obvious turning point in the modern era was the establishment of the state of Israel. The latter was the response to a utopian program that was nevertheless quite practical: to grant the Jews a nation-state like many other nations in the world, and to concentrate therein a large proportion—and ideally an absolute majority—of the global Jewish population. Between the belief in a sovereign territorial state and the opposite outcome of decentralized Jewish dispersion with many centers, reality positioned itself somewhere in the middle. However, demographic trends since the end of the Second World War have absolutely tended more in the direction of Israel and less to the Diaspora.

Over recent decades the world Jewish population has risen—from 11 million at the end of the Second World War to 15.7 million at the start of 2023, in comparison to 16.5 million Jews prior to the war and the Holocaust. The Jewish community in Israel grew from half a million people in 1945 to 7.1 million in 2023, while the number of Jews in the rest of the world declined from 10.5 million to 8.6 million. The proportion of Jews who live in Israel out of the total number of Jews in the world rose from 5% in 1945 to 45% in 2023. These are therefore two completely different and contrasting profiles of demographic development.

A systematic analysis of the Jews in the world reveals a high correlation with the Human Development Index of their countries of residence. The HDI was developed by the United Nations (United Nations Development Programme 2020) as a synthetic measurement of three components: the collective health of a country (based on infant mortality and life expectancy); the education level (based on the average number of years of education attained); and the level of income (which is measured in real terms based on the weighted purchasing power of the US dollar in a given country). There is a strong positive correlation between the HDI of a country and the number of Jews in its population, but the stronger and more prominent positive correlation is with the proportion of Jews within the country.

Since its establishment, Israel is the state whose Jewish population has grown the most in absolute terms, and sometime around the year 2015 it housed the largest Jewish collective in a single country in the world—subject to the definition of core population, rather than the population eligible for the Law of Return. In demographic research, the core population includes all those who declare themselves Jewish or who have Jewish parents, and who have no other religion (DellaPergola 2023). Alongside rapid population growth, Israel’s HDI rose to around 20th in the world amongst 190 countries. In relative terms, from 1980-2020 the Jewish population in Israel saw the second-fastest percentage growth compared to Jewish populations around the world. It more than doubled itself thanks to substantial immigration, primarily from the former Soviet Union (FSU), and a relatively high, stable and even increasing fertility rate. Jewish population growth was fastest (multiplying by a factor of more than three) in Germany, which also drew immigrants, primarily from the FSU, but with a Jewish population growth rate of some 2% more than in Israel. In third place was Australia, and then Canada. The population of Canadian Jews, which grew by 28%, grew faster than that of the United States (14%, based on our corrected evaluation of the 2020 Pew Survey (Pew Research Center 2021). The other Jewish communities shrunk—with the decline in the FSU being the most prominent.

There is a simple lesson about what environment is suitable for the prosperity of Jewish communities, or at least for their stability. Good socio-economic conditions attract and retain large Jewish populations. It can also be hypothesized that in developed countries, the political regimes are democratic and tolerant of diversity and pluralism, and they are thus open to the autonomous development of Jewish communities, at both the individual and institutional level. If this lesson is correct, it is powerful for charting the future of the Jews, if not forecasting it. Emotional connection to a place and dreams are essential for the existence of the collective, but they are not sufficient without a worthy, functioning subsistence framework. The power of this statement applies around the world, including in the state of Israel.

Jewish Presence at the Local Level

At the local level, Jewish populations are concentrated in key metropolitan areas around the world (DellaPergola 2023). There are varying degrees of Jewish presence amongst the overall local population. There is no place in the world where Jews make up 100% of the population, but in two places in the State of Israel—the Tel Aviv district and the central district—Jews make up over 90% of the population, while the others are relatively small numbers of Arabs. Jews are defined here broadly and include family members and relatives of Jews who are eligible for the Law of Return. In three other districts of Israel—the South (of which Beer Sheva is the capital), Haifa and Jerusalem—Jews make up between two-thirds and 80% of the total population, while the proportion of Arabs in these regions is higher. In the northern district of Israel Jews are less than half of the total population. And finally, in the Judea and Samaria region (the West Bank) Jewish residents comprise some 15% of the total population, while the majority are Palestinian residents. This means that in Israel there is a Jewish majority in five of the seven regional administrative districts, as they are defined by Israeli law (not necessarily by international law). The dream of a Jewish majority was only partially fulfilled in the State of Israel, and it is a significant question to what extent this aspiration is still important, and whether reality is moving towards or away from it.

In the rest of the world the Jewish human ecology situation is completely different. The greater New York region is the only one outside of Israel in which over 10% of the population is Jewish (though still less than the percentage in Judea and Samaria). In three metropolitan areas in the United States—south Florida, Philadelphia and San Francisco—Jews make up 5-10% of the total population; in six regions in the United States—Los Angeles, Washington D.C., Baltimore, Boston, Chicago and San Diego—and in Toronto, Canada, they make up 3-5% of the total. In four other metropolises around the world—London, Paris, Atlanta and Buenos Aires—they make up 1.4-3% of the total. The Jewish population in other countries and cities in the world constitutes some 15% of world Jewry, and is characterized by smaller local numbers and a lower proportion of the total local population. This typology of population size and density emphasizes (without fully expressing) the ability of Jewish communities to establish predominant patterns of political, socioeconomic and cultural presence. The central locations with the most developed transnational networks in which the decisive majority of Jews live today offer the kind of environment likely to support Jewish life in the future as well. If in the future cities or metropolitan areas of this type develop in other places in the world, it can be assumed that the chances will rise of finding large Jewish populations there.

Demographic Change Factors: Migration

In relation to potential scenarios of future demographic shifts, there are three principal factors to consider. The first is international migration, which stands at the base of the renewed geographic dispersion of Jews around the world. The patterns of change due to this factor are the most consistent and largely predictable. The second factor is the balance of Jewish births and deaths. The third factor is the balance between people joining the Jewish collective and those leaving it, whether this is via a formal conversion process or in some other manner. These change factors were discussed in detail elsewhere, and we will review them only briefly (DellaPergola 2011).

International migration has been perhaps the most influential factor in the history of changing Jewish demography, because of its direct quantitative influence on different regions, and because of the radical changes it generates in the sociocultural environment in which Jewish presence developed. In the distant past the locus was in the Middle East, and afterward in Western Europe. Between the end of the Middle Ages and the early modern era, Eastern Europe arose as the leading center of growth. During the twentieth century the locus, or at least the primary location of Jewish presence, moved from Eastern Europe to North America. Recently Israel arose again, after 2000 years, to the status of the largest Jewish community in the world (DellaPergola 2023).

The high positive correlation noted above between the level of development of host countries and Jewish presence, explains the current strong negative correlation between the level of development of those countries and the inclination of local Jews to migrate. Geographic mobility from weak to strong locations further intensifies this correlation and causes Jewish presence to be increasingly dependent on the good or bad conditions of a given environment. This dependence is not new in Jewish history, and it has a pronounced influence on the analysis of current migration patterns and on those expected in the future. The overwhelming majority of Diaspora Jews live today in countries in which the level of development is higher than that of Israel or equal to it. The chances of a large wave of aliya are therefore very low, unless these countries lose their socioeconomic status or become entangled in destructive geopolitical processes that lead to fatal results for the Jewish population there.

Since independence, Israel has become the primary destination for migration of Jews, and has frequently been the country that absorbed the absolute majority of Jewish migrants in a given year. A strongly positive international migration balance was the primary growth engine of the Jewish population in Israel until the 1970s, and again briefly in the early 1990s during the tremendous wave of aliya from the FSU. Since then, an extremely positive balance between births and deaths of Jews replaced migration as the leading driver of growth. It is common to assume that Jews migrate to Israel (aliya) based on the ideological, religious and sociocultural attraction of the Jewish state for Diaspora Jewry. But an accurate and detailed analysis of the circumstances and development of migration flows over the years shows that each country of origin has its own story and timeline, and there was no simultaneous response of global Jewish communities to processes occurring in the State of Israel (DellaPergola 2020). The overall logic of migration to Israel can be understood only by considering the balance between push and pull factors created by the economic, political and social circumstances in Israel and overseas.

Analysis of migration to Israel from 16 primary countries of origin in eastern and western Europe, North and South America, South Africa and Australia during the years 1991-2019 proved beyond a shadow of doubt the decisive impact of socioeconomic variables on the scope of aliya (DellaPergola 2020). The dependent variable that was examined most closely was the relation between the highest and lowest migration rates to Israel for every 1,000 Jews in a country of origin over the course of the research period. The most efficient explanatory variable was the difference between the unemployment rate in the various countries of origin and in Israel. Unemployment affected high or low aliya rates as an expression of social stability or instability in a given country. When migration statistics are presented with a one-year lag in relation to unemployment statistics, this simple socioeconomic model displays the highest impact on variation in aliya rates between countries (74%).

In other words, three-quarters of the substantial differences in the scope of migration from the different countries to Israel reflect the unemployment levels in those countries and in Israel. Unemployment need not relate directly to the Jewish population being studied, but reflects the sense of socioeconomic welfare in a society in general, including Jews. The evidence discussed here admittedly does not sufficiently relate to the choice of olim (Jewish immigrants to Israel) of where to migrate, which is sensitive to ideology, and to the socioeconomic composition of the olim. But it shows that Jewish migration to Israel—like all migration—is highly sensitive to available material conditions and opportunities. It also became clear that the employment level in Israel is a contributing factor. Conditions of full employment versus periods of high unemployment have substantial impact on changes in the number and percentage of olim, other than during emergency situations of war or deep political crises in countries of origin, when the impact of migration was less dependent on the state of the economy. An illustration of these findings is the aliya from France in the twenty-first century. Despite tremendous sensitivity to antisemitism and terrorist attacks that took place there in the past few years, the graph of the number of olim precisely tracks the graph of unemployment in France, and not the timing of terror attacks. This is similar to the situation in other countries that did not experience terror attacks and incidents of extreme antisemitic (DellaPergola 2020).

A parallel assessment can be made for emigration factors away from Israel. The connection between the Israeli economy and the rate of emigration during the years 1991-2019 was very strong. The unemployment rate in Israel managed to explain a very high proportion (68%) of the annual variation in those joining the ranks of Israelis abroad for a period of a year or more. In other words, the ongoing economic situation in Israeli is a powerful factor in the country’s ability to retain or lose its residents to other more attractive places in the world, even if only temporarily—much more so than security or ideological concerns.

In recent years, the predictive power of the economic situation on the aliya rate in proportion to the local Jewish population, was eight times greater than that of antisemitism (DellaPergola 2020). The data convincingly demonstrate how global Jewish migration has functioned in the recent past. We are not capable of predicting the future of the global or Israeli economy, but it is clear that Israel’s position in the world economy relative to other countries will translate into its ability to act as an attractive location for new olim, and the opposite—in the case of a severe and prolonged economic crisis Israel may lose a large number of residents. Above all, it is essential to understand that future trends of immigration and emigration will not be based on hopes and fears. They will reflect rational processes that can largely be tracked in real time and even forecast in advance.

The Family Engine and Age Profile

The other principal engine of growth (or decline) of Jewish population is natural expansion (or deficit)—the difference between the number of births and number of deaths. Over the last tens of years, natural increase was high in Israel—actually the highest of all developed countries—and very low or negative in most Jewish communities in other countries. In Israel the Total Fertility Rate (TFR)—the index of the number of children born on average per woman—was three or more around the year 2020. The high birth rate in Israel—apart from the effect of religiosity on family size—is explained by a combination of the improved economic resources available to families and the widespread public sense of optimism and expectation of life improving in the future (DellaPergola 2022b). There is almost no Jewish community in the Diaspora that today reaches an average fertility rate of two Jewish children; this reflects common tendencies of refraining from marriage or marrying late (DellaPergola 2011). An additional factor for low Jewish intergenerational growth across the Diaspora is the high rate of marriage between Jews and non-Jews, only some of whose children will receive a Jewish identity from their parents, or choose one themselves.

Birth and death rates, and sometimes also changes caused by migration, determine the younger or older age profile of a population, which in turn impacts the likelihood of the future birth and death rate. Due to the relatively high fertility rate of three children on average in the Jewish population—and in the Arab population in Israel—the country has a relatively young age structure in comparison to other developed countries, with noticeable differences between the various population sectors.

Joining and Leaving Judaism

In a human collective like the Jewish population, which is defined by symbolic, cultural or ideological criteria, a third form of demographic changes exists, in addition to the routine physical transition of individuals between life and death and to geographic movement from place to place. This is the net balance between those joining the collective and those leaving it, whether via a formal transition ceremony or informally. The Jewish minority in various countries has suffered in the distant past from legal or other types of discrimination in relation to the rest of society, with negative consequences on community retention. Furthermore, the processes of social integration and assimilation have caused a marked erosion of the population. During the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, there were frequent expressions of a voluntary drive to end the abnormal situation of the Jews as different and often discriminated against. This led to highly visible departures and to other forms of erasure, mainly in relation to Judaism, which was perceived as a religion. For many others, changing the perception of Jewish identity from religious to national helps to maintain a new and more secular form of Jewish belonging. Recently, together with a general process of secularization, assimilation has expressed itself more as a slow distancing from organized Jewish life due to personal and family circumstances, rather than as a deliberate decision with roots in ideological awareness. In most European countries the majority of mixed couples do not raise their children in a Jewish framework.

In American society changes of religion have been relatively more common than in the rest of the world. Surveys have repeatedly found that communities of Jews, Catholics and mainstream Protestants tended to lose members, while Evangelicals, Eastern religions and those of undefined religion (i.e. people with no religion or of unknown religion) tended to grow (Kosmin et al. 1991; Kosmin and Keysar 2009; Kosmin and Lachman, 1993; Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life 2008; Pew Research Center 2015; Smith 2009; Rebhun 2016). The Jewish population surveys by the Pew Research Center from 2013 and 2020 (Pew Research Center 2013, 2021) found an intermarriage rate that recently surpassed 60%, while the total number of those leaving Judaism was twice that of those joining. An additional Pew survey from 2015 on religion amongst all Americans estimated a Jewish loss of some 600,000 people due to changes of religion over the course of their lifetime (Pew Research Center 2015). In 2020 10% of Americans who were raised Jewish by religion, and 24% of those raised as Jewish without religion, disconnected from their Jewish identity (Pew Research Center 2021). These findings confirm the impression of a negative balance between joiners and leavers.

In contrast, in certain Latin American countries such as Mexico the rate of intermarriage was much lower than in the United States, and in most cases ended with the non-Jewish partner converting to Judaism. In Europe assimilation and leaving Judaism developed much earlier than on other continents, but contemporary accounts show that the process of assimilation is slowing down and in some cases reversing its direction, perhaps in response to negative anti-Jewish pressure from the external environment (DellaPergola and Staetsky 2020). In contrast to the above, in Israel marriages between Jews and Arabs are extremely rare, but many mixed couples have immigrated from the former Soviet Union and other states (DellaPergola 2017a). The number of potential joiners of the Jewish collective in Israel is estimated at a few hundred thousand, but the local Chief Rabbinate has implemented a very strict conversion policy (Fisher 2019), which has created widespread frustration and deterred many from even submitting a request to convert. It should be noted that the definition of core Jewish population supposedly includes people who choose to be Jewish even if they do not undergo conversion (Jews by choice). However, if or when they need the services of a Rabbi, these people will not be recognized as Jews.

Population Forecasts: Successes and Limitations

Before we examine a number of scenarios for the potential development of future Israeli and Jewish demography, we will first raise some issues regarding the general reliability of population forecasts. The validity of demographic forecasts for properly capturing actual trends is sometimes questioned. To what extent can analysis of the past yield valid forecasts for the future? The answer depends on researchers’ skills, on understanding the ongoing dynamics of population change and on the chosen research methods.

Demographic forecasts can be reliable, such as for example those carried out by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) over the years: The CBS forecast the size of the population of Israel in mid-2020 on the basis of the statistics for mid-2005. In 2005 there were 6,930,000 Israelis, including 5,573,000 Jews and others and 1,357,000 Arabs. The forecast for 2020 in their intermediate scenario (out of a high/low range of scenarios) was 8,673,000, of whom 6,679,000 were Jews and others and 1,976,000 were Arabs. In practice, in 2020 the population size was 9,212,000 of whom 7,275,000 were Jews and others and 1,938,000 were Arabs. The forecasting error was minimal for the Arab population (+2%), but was not insignificant for the Jews and others (-7.9%), actually approaching the higher range of the projection. The total forecasting deviation for the overall population of Israel was -5.9%. The primary reasons for this were an underestimation of the number of new immigrants arriving to Israel and of the Jewish fertility rate, both of which were expected to decline but in practice rose during the forecast years.

A better example of a reliable population forecast was that carried out for the Jerusalem Municipality on the basis of 1995 statistics as part of a strategic plan for the city until 2020 (DellaPergola 2008; DellaPergola and Rebhun 2003). The work related to the entire municipal population and presented the Jewish and Arab sectors separately. In 2020 those forecast statistics could be compared with the true population statistics, a moment anxiously anticipated by those who deal with such simulations. In 1995 Jerusalem had 591,400 residents. The population forecast for 2020 for Jerusalem was 947,000, and the real number was 952,300—a total error of -0.6% in the forecast. The total errors accumulated over 25 years regarding the Jewish and Arab populations were +0.6% and -2.4%, respectively. Such gaps seem small, especially considering that the Jewish population of Jerusalem grew by 40% during the period of the forecast, while the Arab population grew by 110%, or in other words, more than doubled. Such a high level of accuracy regarding such a dynamic demographic context was achieved by breaking the general population down into dozens of smaller forecast regions, each of which had its own special demographic dynamic. In each age group and for each five-year period the expected impact of each component of demographic change (births, deaths, international migration, domestic migration) were taken into account. Partial findings were then recompiled, resulting in good results and reflecting a methodology that could also be applied to nationwide population forecasts.

Population forecasts can therefore provide a reasonable road map, while considering that unexpected events (such as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the breakup of the Soviet Union two years later, or the Covid pandemic in early 2020 and the Swords of Iron War of 2023) may change the course of history, with weighty implications for global trends, world Jewry and Israeli society.

What Lies Ahead for the Population Between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River?

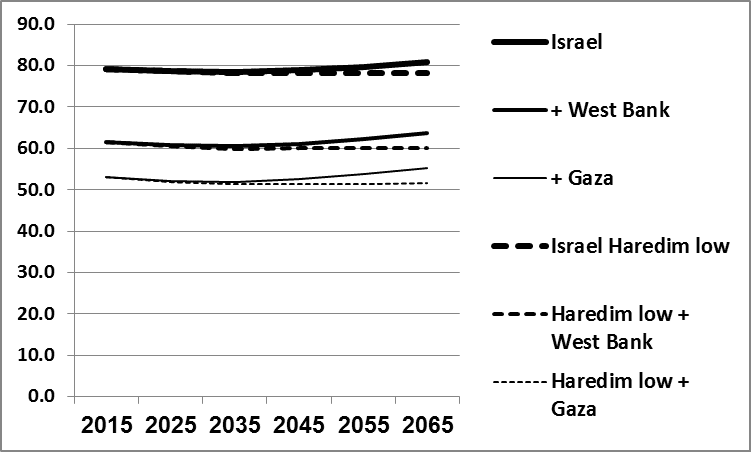

Now we will look ahead and examine firstly the demographic balance between Jews and Palestinians in the entire region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, or in other words, the entire area of the Land of Israel during the time of the British Mandate along with the Golan Heights. Changes in the existing balance will decisively determine the cultural, social and political character of the State of Israel (DellaPergola 2016; DellaPergola 2021). The forecast for Israel presented in Figure 1 below is based on CBS scenarios, not including international migration. The projections presented are based on relatively conservative assumptions about fertility levels in the various segments of the population. The primary assumption presented is the continuation of existing trends of stability or moderate decline, unlike the majority of Western countries where fertility is low. Regarding the haredi (very orthodox) population two fertility assumptions were tested, one of stability and one of some moderation. It is clear that in the event of a severe overall moderation of birthrates, the population in reality will be smaller than that presented here.

As noted above, the impact of migration can be significant, but there are endless scenarios of immigration or emigration, on small or very large scales due to a range of circumstances. It is clear that different scales of migration can change the results of the forecast in either direction, but there is no way to accurately predict what developments will occur in practice. The Palestinian population forecast for the West Bank and Gaza was carried out by the author independently, separately from other existing projections (DellaPergola 2021; PCBS 2022; United Nations Department of Economics 2022). The total population of this region is likely to grow quickly, both in total and within each of its two components—the State of Israel and the Palestinian territories. By 2065, the current number of over 14 million residents in the whole area between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River is likely to nearly double.

History shows that in modern times a Jewish majority across the full territory of the Land of Israel was first achieved in the 1950s, in the wake of the large wave of aliya that accompanied the establishment of the state, and the large wave of Palestinians emigrating from the land of Israel due to the 1948 war (DellaPergola 2021). Afterwards, population growth was faster amongst Jews until the 1970s, and amongst Arabs in the following years. The primary reason was much higher natural growth amongst Arabs compared to Jews within Israel and in the territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—natural growth that more than balanced out the impact of Jewish aliya (with lone exceptions during the peak years of migration from the Soviet Union in 1990 and 1991). More rapid growth in the Arab-Palestinian sectors is likely to continue until the 2030s, at which point Jewish population growth is expected to slightly outpace it. Such a shift is expected to reflect the rapid growth and proportion of haredi Jews amongst all Israeli Jews (see description below). In 2065 in the entire territory of the land of Israel, the enlarged total Jewish population—including non-Jewish household members who are eligible for the Law of Return—is likely to reach 16 million people and the Arab population is likely to reach 13 million—in total, almost 30 million people.

The forecasts for the population of Israel in Figure 1 are based on the intermediate projection from a wider set produced by the CBS. If we assume that the population growth of haredi Jews will gradually moderate (in accordance with the lower CBS forecast) as a result of greater integration into broader society and especially into the workforce, the entire Jewish population will grow at a slower pace, and as a result the proportion of the Arab population will increase.

Figure 1. Projected rate of Jews as a proportion of the entire population of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, 2015-2065 – different versions | Source: Central Bureau of Statistics processed by author; DellaPergola 2021.

Using a constant definition of the Jewish population broadly defined—including non-Jews eligible for the Law of Return—, within the borders of the State of Israel, by the second half of the twenty-first century there should be a substantial Jewish majority of close to 80%. The picture changes if the calculation includes the Palestinian territories and their populations, in whole or in part. If all of the area and population of the West Bank are added to the territory of the State of Israel, the Jewish majority declines to 60%. This rate would still ensure a Jewish majority across the territory but would render the idea of a Jewish and democratic state uncertain in the face of a statistical reality of a binational state. If the territory and population of the Gaza Strip are also included, the Jewish majority falls to just above 50%, and this would end the project of the Jewish state. As said, all of these forecasts reflect the intermediate scenario of the CBS. However, if we take the lower projection for the haredi population, the Jewish population will grow more slowly and its majority status will decline accordingly.

It should be noted that the forecasts presented here differ from the estimates I published 20 years ago, when the gap between the growth rate of the Arab and Jewish populations was much larger (DellaPergola 2003). At that time I expected that Jews (including hundreds of thousands of non-Jews eligible for the Law of Return) would become a declining minority in the Land of Israel; today this is no longer expected. The reason is that in the interim there has been moderation, later than expected but significant, in the fertility levels of the Arab population components. At the same time, the fertility level of the haredi sector of the Jewish population has not moderated, with slight fluctuations reflecting the current state of families’ financial situations. In recent years, there has been a significant convergence in fertility levels between most elements of the Jewish and Arab population, with the exception of Bedouin women in the south of the country and the haredi sector, and some Jewish families in Judea and Samaria. However, due to differences in age composition and the fact that the Arab population is younger than the Jewish population, Arab birth rates are still higher and death rates are still lower than in the Jewish sector as a whole. This is why the natural growth of the Arab sector is higher, even if there are no differences in the level of fertility. These gaps should moderate over the coming decades.

In each scenario, the impact of current and expected demographic trends will be of decisive importance for the cultural, economic and political character, and especially for the bilateral religious-national balance in the geopolitical ecosystem of Israel and the Palestinian Authority. The expected effects of demography oblige the Israeli leadership to pay close attention to strategy and operational planning. The new fact that emerges from these estimates is the dependence of the overall Jewish population on the growth rate of the haredi sector within it, when again, a significant increase or decrease in the size of this sector can change the picture one way or the other. If the haredi sector grows to a lesser extent, the rate of growth of the entire Jewish population will decrease and the proportion of the Arab population will increase accordingly. On the other hand, while an increased weight of the haredi sector may make it possible to maintain the current demographic balance, it raises other questions: To what extent will members of this sector be able to better integrate into the economy and improve their living conditions by achieving greater economic independence, reducing poverty and dependence on public subsidies? Will this lead to a situation of families who follow tradition, but are smaller than current families? What is certain is that the key to Israel's demographic future depends mainly on haredi demographics. A kind of “sacred alliance” is created between the different—more or less religious—sections of Israeli Jews within Israel’s changing demographics. The question is whether this alliance will also be expanded to other aspects and areas of common life in the country. In any case, demographic change will produce an entirely different Israeli society by the middle of the twenty-first century and onwards.

Sectoral Population Growth in Israel and its Implications

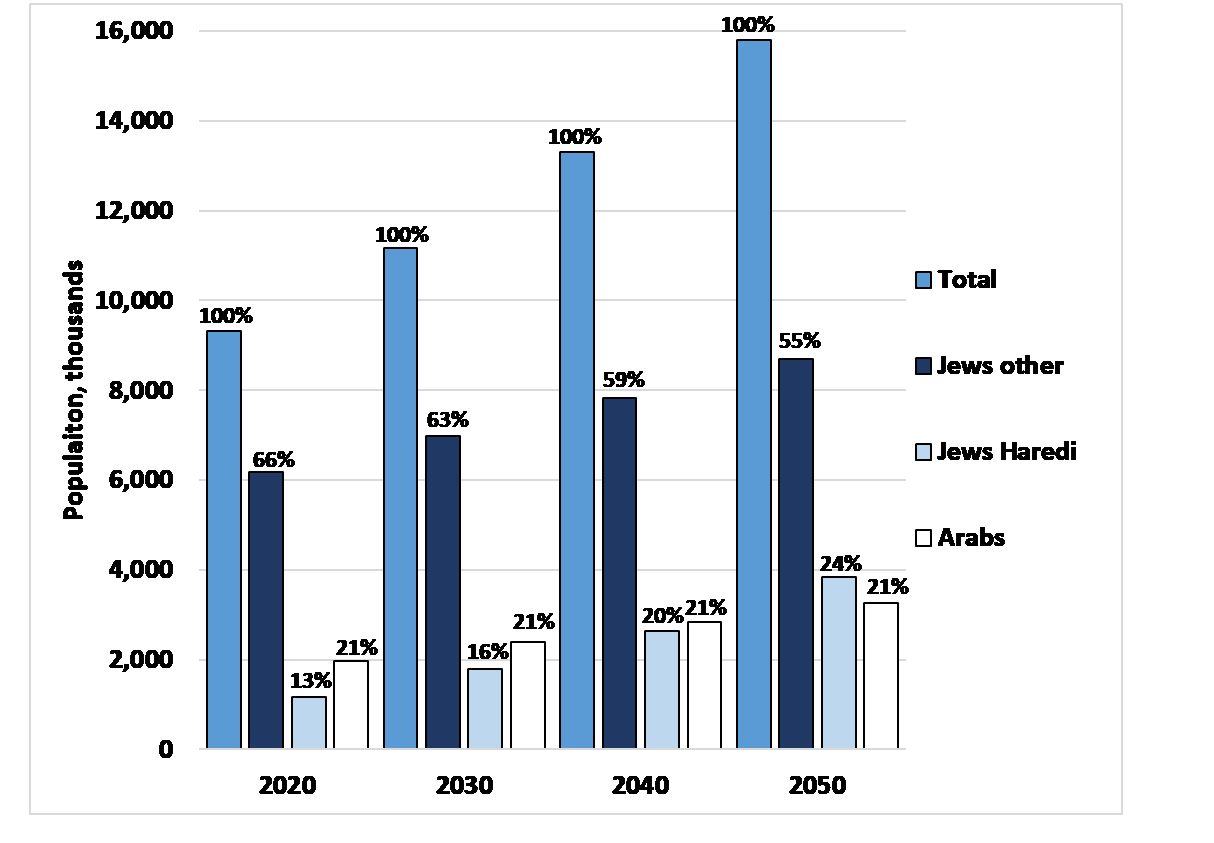

The expected changes in the population of the entire territory of the Land of Israel depend in a large part on what is expected to take place within the State of Israel’s borders. When considering Israel’s future, a central question is whether the population and the various sectors or “tribes” therein are expected to develop in directions that conform to the aspiration of being a sovereign independent state that is Jewish (or in other words, open to all Jews around the world), democratic and competitive. One of the important aspects of this demographic change is the non-uniform and non-synchronized pace of change amongst the different population sectors, which will have important implications for the aggregates at the end of a given study period (DellaPergola 2017b). National population forecasts by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics can offer a partial answer, which extend 30 years, covering the period from 2020 to 2050 (see Figure 2). It should be noted that the forecast presented here is the latest existing full forecast, and CBS is currently working on an updated version. While there is no expectation of extreme shifts in the factors of demographic change that will supposedly affect the coming years, sudden and unexpected events such as the collapse of states and dramatic wanderings of their peoples may absolutely have an influence over the long term. An event like the Covid pandemic can also have an affect due to changes that accumulate in the population composition over the long term. A war event such as Swords of Iron can have very different effects on migration.

The current forecast divides the population of Israel into three main components: Arabs, haredi Jews and other Jews, with the latter including the full spectrum from secular to national-religious, as well as those members of the broadly defined Jewish sector who are not recognized as Jewish under religious law by the Chief Rabbinate and the Ministry of the Interior (and therefore, by the CBS itself). This typology is admittedly too raw, but it is acceptable for initial analytic needs when considering the notable differences between each group in comparison to the other two in relation to religion and religiosity, life patterns, residential concentrations, socioeconomic characteristics (especially workforce participation rates), marriage and fertility patterns and political stances, including attitudes toward cultural pluralism and democracy. This typology assumes there will not be substantial numbers of people transitioning between sectors. The basis for this is the firmness of social boundaries between these sectors. Multigenerational intra-Jewish empirical analysis indicates strong resilience of the haredi sector in the face of secularization processes that are certainly taking place in the religious sector as a whole (Keysar and DellaPergola 2019).

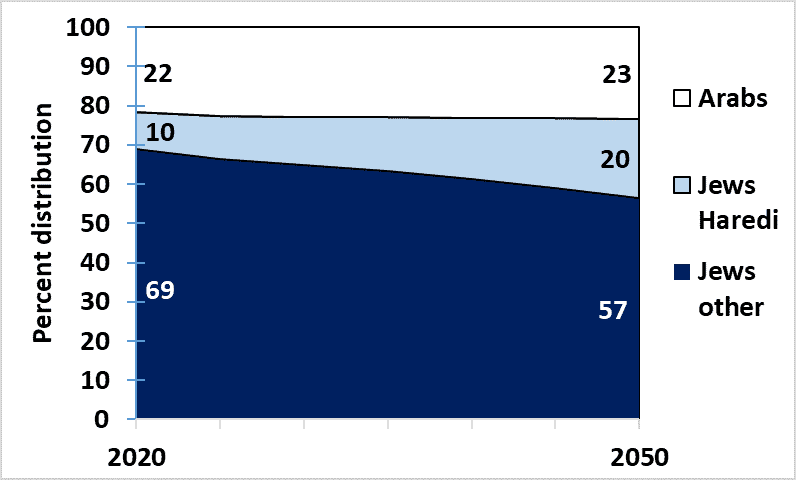

The total population projected for the state of Israel (without the West Bank and Gaza) is expected to grow from over 9 million people in 2020 to nearly 16 million in 2050. A decline in the annual population growth rate is expected, from 2% at the beginning of the period to just over 1.5% at the end of the period. What is expected to change is the relative proportion of each of the three main population sectors, which reflect their differing growth rates. In Israel in 2020, two-thirds of the population were non-haredi Jews, 21% were Arabs and 13% were haredi Jews. Between 2040 and 2045 the number and proportion of haredi Jews are projected to exceed those of Arab citizens of Israel, with a gradual reduction of the non-haredi majority. In 2050 non-haredi Jews are projected to be 55% of the total population of Israel (that is, excluding the West Bank and Gaza), with 24% haredi Jews, and 21% Arabs.

Figure 2. Population forecasts by main ethnoreligious groups, Israel 2020-2050 | Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, processed by author.

In addition to the projection of overall demographic change, it is essential to see how expected changes are likely to influence specific age groups that in practice determine the profile of social needs, the type and extent of services needed to meet these needs and the investment policy necessary to establish and manage these services. In the following I will focus on four different age groups of Israelis, in descending order: those aged 65 and above, those aged 20-64, 18 and 19-year-old, and under 18s.

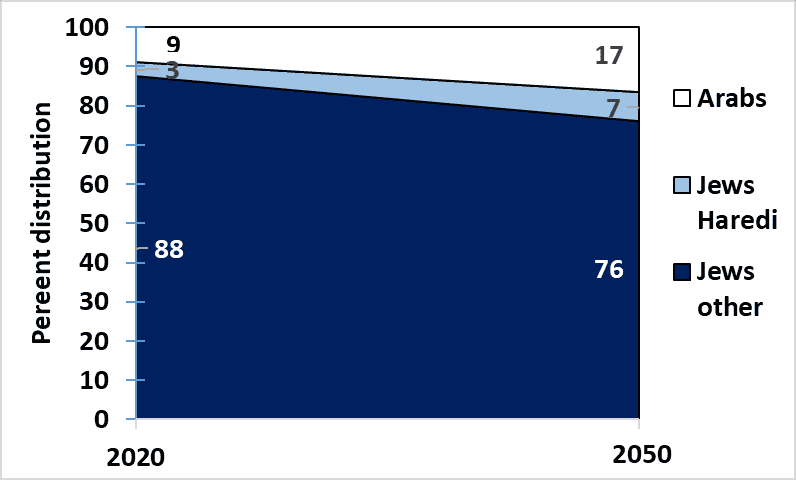

Figure 3 presents the projected structural changes between 2020 and 2050 amongst the population aged 65 and older. Their number in 2020 was 1,135,700 and it is projected to grow to 2,423,100 in 2050—an addition of 1.3 million or 113% (in other words more than doubling). The aging process takes places naturally in each population, and has two aspects. One which applies to the entire population is that it typically reflects the gradual reduction in birth rates, and therefore the reduction in the proportion of children within the total population. Consequently, the relative proportion of the elder population group must grow. The second aspect relates to the absolute growth in the number of elderly people, which in most countries reflects the consistent increase in life expectancy for all ages, including the oldest citizens. Due to the increase in the number of elderly people, and to the relative proportion of the oldest age group within the category of all people over 65, over time all needs relating to medical care, hospitalization and welfare service grow significantly. The financial dependence of the elderly on the existing private and public sector support system also grows. The oldest group in this age profile includes a large population of retired people, although over time the tendency to work beyond the official retirement age is increasing in some sectors, especially amongst those with tertiary education. Changes in the retirement age can affect the functioning of older people, but at this stage not their distribution by categories of religion and nationality.

Figure 3. Population 65 years and older, by main ethnoreligious groups, Israel 2020-2050 | Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, processed by author.

The State of Israel has a relatively young age profile in comparison to other developed countries, due to high fertility rates in the past and present. But as mentioned, the aging process will lead to more than double the number of people aged 65 and up by the year 2050. In the internal composition of this age group in Israel there is a dominant weight to the Jewish non-haredi sector, with 88% of the total population as of 2020, expected to drop to 76% in 2050. The rate of people aged 65 and up in the other two sectors is lower—9% of Arabs and 3% of haredi Jews in 2020, and is supposed to grow rapidly to 17% of Arabs and 7% of haredi Jews by 2050. In other words—the relative weight of these two smaller sectors, Arab and haredi, will double in the next 30 years, although they will remain a minority.

Figure 4 presents the projected changes in the composition of the 20-64 age group. This group represents the primary backbone of families working, earning and consuming; it requires solutions of employment, housing, and other suitable services. Their number in 2020 was 4,799,300 and is projected to grow to 7,728,500 by 2050—an addition of over 2.9 million people, or 61%.

Figure 4. Population 20-64 year-olds, by main ethnoreligious groups, Israel 2020-2050 | Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, processed by author.

The dominant weight of the Jewish non-haredi section in this age group is expected to shrink from 69% of the total population in 2020 to 57% in 2050—still an absolute majority of all working-age people. Arab adults of working age are expected to remain relatively stable as a proportion of the total population, with their percentage rising from 22% in 2020 to 23% in 2050. In contrast, there is a significant expected increase in the number of 20-64 year-olds in the haredi sector, whose portion of the population will double from 10% in 2020 to 20% in 2050. If calculating the numbers as proportions within the Jewish public alone, there were 87% non-haredi in 2020 compared to 13% haredi, and this ratio will change to 74% vs. 26% in 2050.

Figure 5 presents the age breakdown for 18 and 19 year-olds, who are the primary target for recruitment to security forces. Their number in 2020 was 284,500 and is expected to increase to 481,500 by 2050—an increase of nearly 200,000 people or 69%. There are substantial limitations on the scope of actual enlistment in Israel, according to gender and population sector, and due to the non-enlistment of certain sectors and the exemption from enlistment granted to others. Yet, it is still of interest to see the projected numbers for these two points in time.

In 2020, 53% (in other words, just over half) of the 18-19 years old were non-haredi Jews, 18% were haredi Jews and 29% were Arabs. In 2050 this breakdown will change—47% (or less than half) are projected to be non-haredi Jews, 32% haredi Jews and 21% Arabs. If calculating the numbers within the Jewish public alone, in 2020 there were 75% non-haredi Jews vs. 25% haredi. In 2050 59% of Jews of potential enlistment age are projected to be non-haredi vs. 41% haredi.

Figure 5. Population 18-19 year-olds, by main ethnoreligious group, Israel 2020-2050 | Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, processed by author.

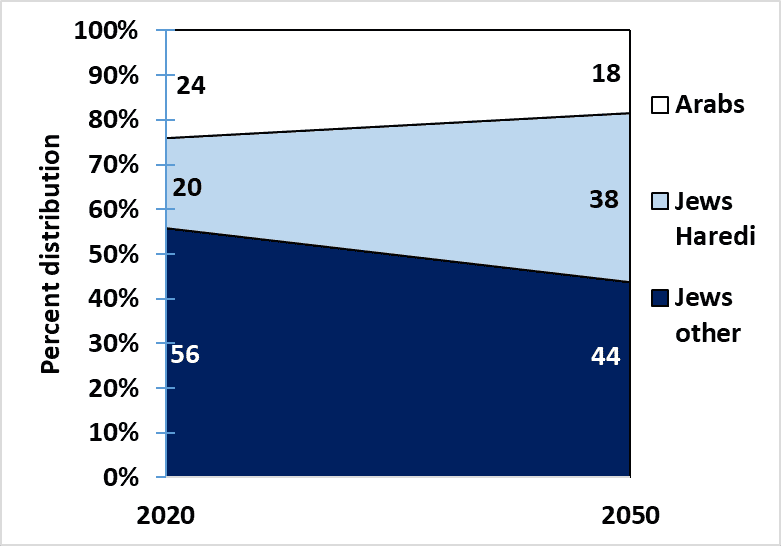

Figure 6 repeats a similar observation for those aged 0 to 17, in other words children and adolescents in need of early childhood services and the education system. Their number in 2020 was 3,092,000 and is projected to grow to 5,170,300 by 2050—an addition of almost 2.1 million people, or 67%. Amongst the growing Israeli population, the rate of non-haredi Jewish children and adolescents was 56% of the total in 2020, and is projected to shrink to 44% by 2050. The proportion of haredi Jews is projected to grow from 20% to 38% of the total population of children and adolescents, and the equivalent proportion of Arabs is projected to decline from 24% in 2020 to 18% in 2050. In relation to the Jewish population only, according to this projection, the proportion of non-haredi Jewish children is likely to decline from 74% in 2020 to 54% in 2050, and the rate of haredi children is likely to increase from 26% to 46% as a percentage of all Jewish children. In other words, non-haredi Jewish children will still constitute a majority of all Jewish children and adolescents under age 18, but not of the total of that age group in Israel.

Figure 6. Population 0-17 year-olds, by main ethnoreligious group, Israel 2020-2050 | Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, processed by author.

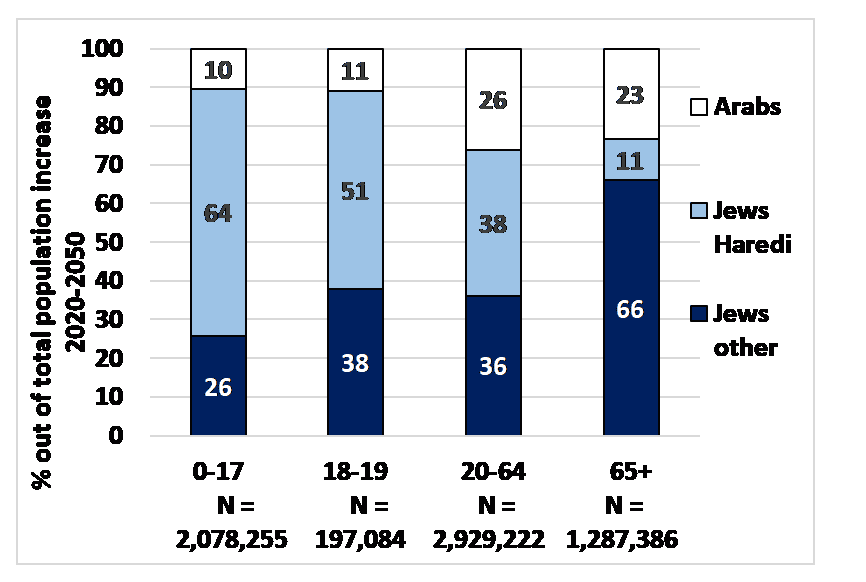

The implications of these projected changes become clearer in Figure 7 below, which presents the expected population increases between 2020-2050 for each given age group and for each population sector. Amongst the group of 0-17 year-olds, the expected growth from 2020 to 2050 reaches over 2 million children and adolescents, of whom 10% are expected to come from the Arab sector, 26% from the Jewish non-haredi sector and 64% from the haredi sector. In other words, nearly two-thirds of the total population increase expected in the preschool and school-aged population in Israel is expected to be from haredi young people. This has far-reaching implications on planning the national education system—public and private sectors, teacher training, construction and other physical infrastructure and additional aspects of allocation of state resources to different sectors.

Regarding the potential enlistees to the IDF aged 18 and 19, between 2020 and 2050 38% of the additional 200,000 young people is expected to come from the Jewish non-haredi sector, 51% from the haredi sector and 11% from the Arab sector. If we examine the breakdown of the expected increase to the Jewish population only, 43% are projected to be non-haredi vs. 57% haredi. In other words, if we follow the recent saying: “50% for the army and 50% for the Torah,” it would be necessary to significantly increase the scope of haredi recruitment to meet this quota (the value of which is debatable).

Regarding the group of 20-64 year-olds, which as mentioned is the backbone of the future workforce, an increase of nearly three million people is projected between 2020 and 2050, of whom 36% are non-haredi Jews, 38% haredi Jews and 26% Arabs. Beyond the structural change noted between sectors, the significance of the data lie in the different tendencies to enter the workforce among those belonging to each of these population groups. Attention should be paid to the significant gender gaps that exist within each sector. The data indicate that 64% of the increase in the working age population in 2050 is projected to come from population sectors with low participation in the labor force—who today are mainly haredi men and Arab women. In other words, the portion of the total population of those likely to work is projected to shrink considerably, which entails negative consequences for the economic productivity of Israeli society as a whole. An alternative scenario is only possible if the socioeconomic habits of the various sectors of the population change, implying higher workforce participation among the Arab and haredi sectors—which may help preserve future employment patterns at a level closer to the current one.

Finally, regarding the segment of those aged 65 and above, out of a projected addition of more than one and a quarter million people at these ages, 66% are expected to come from the non-haredi Jewish sector, 11% from the haredi sector and 23% from the Arab sector. In this context, it is important to emphasize once again that care for the elderly population is not only a matter of resources and structures, but also requires an understanding of and sensitivity towards the cultural aspect of contact between caregivers and their clients. Appropriate training is therefore required for a professional workforce that will be responsible for a public that, as mentioned, is not homogeneous in terms of its needs and worldviews.

Figure 7. Percent composition of expected population growth, by main ethnoreligious group and age, Israel 2020-2050 | Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, processed by author.

To summarize this section, the projected estimates are not only meaningful in relation to the overall changing structure of Israeli society between the start and end dates of the forecast. The much more significant matter is that the population composition of Israeli society in terms of the main ethnoreligious groups—which themselves have explanatory value for future population growth—, is set to alter dramatically over the next three decades. The difference is not only a matter of theoretical tallying but involves drastic changes for the functional essence of each of these different age groups, in accordance with the various characters, needs, expectations and contributions of each different population sector. The expected additional populations at each age level configure dramatic shifts in the new human capital joining the pre-existing one, and in particular the investments required for each population sector. The results will reverberate for Israeli society as a whole.

Looking Outside the Box: Changes in the Relationship Between Israel and the Diaspora

The complex challenges of population composition for Israel’s future described above cannot overshadow the fact that Israel is the only growing component of world Jewry, besides a few exceptions. As a result, the population of Jews in Israel as a proportion of all world Jews grew consistently from 5% in 1945 to 45% in 2023. Israel currently increases its proportion of the total world Jewish population by half a percentage point every year. This means that by the mid-2030s Israel might possibly be home to half of the Jews in the world, and soon afterwards, to the majority. These estimates depend naturally on the definitions applied to the boundaries of the Jewish collective. The approach of the core Jewish population used here (DellaPergola 2023) relates to a collective that can be compared across different countries and Jewish communal cultures around the world, in contrast to broader or narrower criteria for this definition, which are used in other parts of the world or by one or another stream of the Jewish collective but are not comparable globally.

Outside of Israel, Jewish population projections consistently indicate numerical decline in most countries. The most attractive Jewish communities are in English-speaking democratic states, which are wealthier and have historically allowed for a greater degree of multiculturalism. In this context increased attention must be paid to the United States. All past attempts to forecast the future of the Jewish population in the United States predicted an end to growth followed by a gradual, slow decline. Various researchers set the date for the expected turning point at different points between 1990 and 2023 (DellaPergola 2013; DellaPergola and Rebhun 1998-99; DellaPergola et al. 2000; Goujon et al. 2012; Klaff 1998; Pew Research Center 2015a; Pinker 2021; Rebhun et al. 1999; Schmelz 1981).

Such a broad consensus regarding the direction of the process (if not regarding its timing) reflects the clear aging of the American Jewish-identified population after decades of low fertility, and only partial success at integrating a large portion of the children born of marriages between Jews and non-Jews in a Jewish communal framework, although this portion is growing over time. Aging leads to higher death rates, which ultimately balance or overcome the Jewish birth rates. The gradual postponing of the expected end of growth may reflect the lengthening of generations as a result of the higher average age of women at the time of giving birth, as well as the constant increase in the proportion of orthodox and haredi Jews amongst the younger generation. Another factor may be a growing flexibility in including people of Jewish origin in the collective, despite them not seeing themselves as a part of it, but rather of no religion or of a different particularist identity. Along with the expected decline in the size of the Jewish population over the long term, the proportion of orthodox and haredi Jews is expected to rise significantly in the United States and in other areas across the Diaspora. If this process continues or even intensifies, the continued trend of several decades of decline in the number of Jews in the Diaspora may U-turn, although from within a much smaller population. These projected changes in the structure of the Jewish population also involve the rise of more conservative affiliations in the Jewish public towards the general politics of their countries of residence and a small increase in the number of immigrants to Israel, which is typically low.

Regarding the changing context of American Jewry, in particular, we for a long time have been accustomed to a paradigm of a primarily white American society which hosts a variety of Hispanic, Asian and African American minorities, who via various paths of social mobility become absorbed in the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant mainstream (Alba and Nee 2003). This process was sometimes slow and not free of conflicts and difficulties. Jews in the US experienced one of its most significant success stories, after beginning very low on the ethnic, religious and social ladder and climbing close to the top (Chiswick 2020). Recently a few other minority groups, mainly Asian Americans, have risen to a leading place in the ranking of high educational achievement and income. The socioeconomic and cultural integration of Jews was very successful in the wider social context, but their rates of cultural assimilation were also among the highest. The dynamic of immigrant absorption on a broad scale, which brought with it differential population growth rates, deeply changed the population profile of the United States. This change was especially pronounced after the immigration law reforms in the 1960s, which allowed entry and upward social mobility for larger proportions of groups of nonwhite immigrants and their descendants. Population projections predict that between 2050 and 2060 non-Hispanic whites will become a minority of the overall US population (Vespa et al. 2020).

The United States is likely to become a primarily Hispanic or non-white society, with a smaller, more orthodox Jewish community. This is a new scenario with potentially far-reaching consequences, such as a decline in the sensitivity of the United States to the cultural and emotional needs of the Jewish community, including regarding support for the State of Israel, or even hostility towards the Jews due to their being identified with the allegedly colonialist white population. In contrast to past models, in which Jews—mainly of European ancestry—pursuing modernization integrated easily into and sometimes disappeared within the white American mainstream, today a much different model is emerging. In the future, the degree of closeness and osmosis, communication, mutual empathy and knowledge and cultural exchange between Jews and broader American society may be completely different. The distance in terms of historic memory and political sensitivity between Jews and non-Jews may grow significantly.

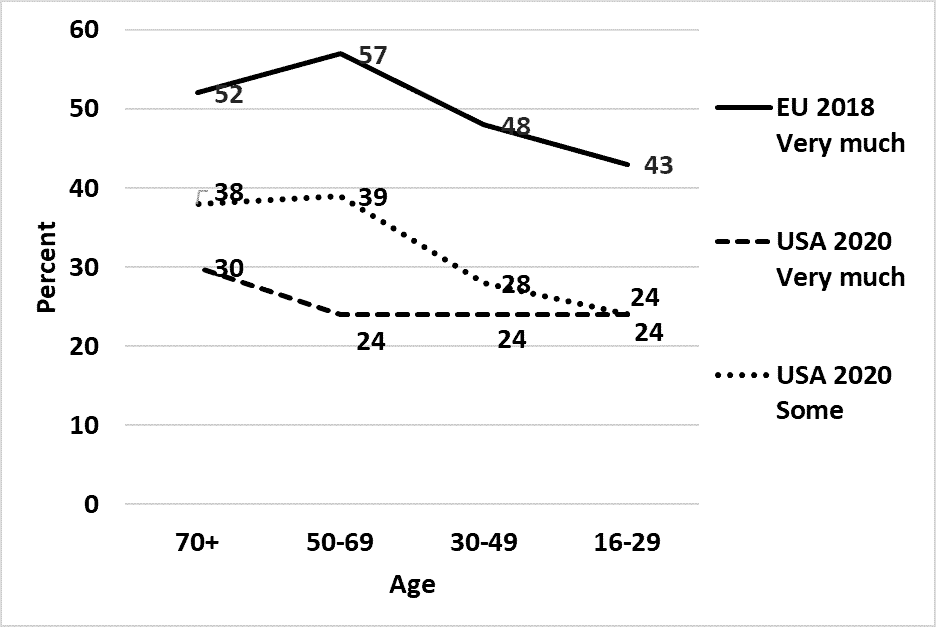

One important component that may be influenced by these expected demographic changes is the scope of mutual relations and support amongst Jews from different places around the world, and especially between the two main concentrations in the US and Israel. The centrality of Israel in the perception and emotions of Diaspora Jews was revealed after 1948 as a central and strengthening element of Jewish identity, but it seems that the documented erosion amongst the younger generation leads to different approaches and meanings in this context (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Rate of Jews reporting emotional closeness to Israel, European Union 2018 and United States 2020 | Source: Pew Research Center, 2021; DellaPergola and Staetsky, 2021.

According to the 2020 Pew Survey (Pew Research Center 2021), the proportion of US Jews who feel that Israel plays an essential or at least some role in their Jewish identity declined from 68% among those aged 70 and up, to 48% (or less than half) among young people below age 30. Of these, the rate of those who felt a very strong connection was 30% of those aged 70 and up, and 24% below age 70. In Europe, based on the FRA survey from 2018 (DellaPergola and Staetsky 2021), the rate of Jews who feel that they have a strong connection with Israel was higher. The rate of those who felt they have an essential connection declined a little among younger respondents, but remained in Europe almost twice as high as in the US. This may hint at reduced empathy and support for Israel amongst Diaspora Jews. On the other hand, the expected increase in the proportion of more religious Jews within US Jewry, while a similar process is expected in Israel, may create a transnational trend of mutual understanding between those who stay Jewish until then, here and there.

Finally, it is important to emphasize the potential effects of political values on the relationship between Diaspora Jew— especially American Jews—and the State of Israel. In Israel there was a certain balance for many years between the progressive and conservative camps, who are divided over central issues such as the legal role of the Supreme Court, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, individual rights, and religion and state, while the government frequently changed hands between the sides. But in the US and other states, an explicit majority of the Jewish public is inclined to a liberal orientation. As long as Israel managed to maintain a domestic political system which could transmit an enlightened image to Jewish audiences with different political orientations overseas, these audiences could see Israel as an important center of reference, despite their different political opinions. A sharp conservative turn—like the one that took place in Israel in 2023—may cause disappointment and alienation to the point of total disconnect between Israel and large liberal-oriented Jewish audiences in the Diaspora. Evidence thereof is beginning to accumulate in major Diaspora countries, where a large majority of the Jewish public has expressed a negative opinion of the Israeli political leadership (Boyd and Lessof 2023; Brym, 2023). The attempted legal reform and the Israeli rabbinical establishment’s hostility towards the major Reform and Conservative movements in the United States harm the traditional paradigm of a covenant of shared fate, which characterized Israel-Diaspora relations over previous generations. The gap created may negatively influence emotional and financial support for Israel as well as interest in aliya and absorption in Israel. The Swords of Iron war may influence in highly contradictory directions the sense of solidarity US Jews feel with Israel.

Discussion and Conclusions

First of all, it should be recalled that the prospective findings reviewed in this article draw heavily on what is already known about the present situation based on long-term trends from the past. However, the continuity of demographic development patterns which we have documented from past generations may actually generate a number of dramatic changes within the Israeli space and regarding mutual relations between the State of Israel and Diaspora Jews.

One aspect is the increasing weight of Israel within global Jewish demography if, as seems possible, the majority of Jewish people globally come to live in Israel—at least according to a definition of who is a Jew that is readily acceptable to most of the Jewish public in Israel and abroad. The Jewish population in most countries outside of Israel is shrinking and aging slowly, besides a few exceptions such as the United Kingdom, which has an increasing haredi population that is growing rapidly, or Canada, Australia and perhaps Germany, which still attract sufficient numbers of Jewish immigrants. There are signs—particularly in the US—of distancing from a sense of shared peoplehood, including significantly weakened affinity of young people towards Israel as a pillar of the contemporary Jewish experience. Continued rapid population growth in Israel is likely to be led in large and increasing part by haredi Jews, which raises questions about socioeconomic functionality and stability, shared core values and a potential increase in poverty here. There is a significant question regarding how sufficient internal solidarity within Israeli society can be maintained in light of increased feelings of alienation, and sometimes even due to the hostility between different opposing extremes of the most religious and most secular (Pew Research Center 2016).

There are also increasingly loud voices being heard opposing a large and overcrowded population in Israel, due to its population growth rate, which is higher than that of any other developed country (Tal 2016). Population growth in Israel’s small territory does reflect strong momentum that will be difficult to halt. By way of paradox, the way to slow the pace of growth would be to slow the rate of births or increase the rate of deaths, or halting migration into the country and increasing emigration out of it. China, for example, used draconian measures to reduce the number of births, but due to the harsh consequences of its distorted age profile it ultimately reverted to supporting a higher birth rate. In Israel, the postponement or avoidance of planned births would likely only come about in the context of a deep economic emergency, a crisis of identity and belief or general demoralization, as has occurred in some European countries where birthrates are extremely low. However, it can be assumed that in Israel the orthodox and haredi sectors would be less affected by such hypothetical changes, and therefore any reduction in birthrates would not be uniform and therefore only impact the secular layers of the future population.

Attempts to increase mortality are typically only found in science fiction, including the development of unequal regulation. Similarly one could subsidize and encourage movements that oppose vaccinations to the Covid pandemic, for example, or cease funding Israel’s excellent health system, which successfully fights illness and mortality. Regarding international migration, as mentioned, emigration from Israel responds sharply and clearly to the Israeli economic situation, including the levels of employment and income in Israel and abroad, overseas investments and the opportunities for personal mobility and professional advancement. The imaginary path to restricting population size in Israel via outward migration would be similar to the approach for reducing births, i.e. a deep economic crisis affecting all layers of society. Aliya to Israel is affected acutely by economic factors acting mainly abroad, but in Israel as well, as discussed above. Regarding the ideological added value of aliya, a clear declaration that Israel is abandoning the old paradigm of the Jewish state and cancelling the Law of Return would suffice.

All of these are of course absurd and unreasonable proposals. The likelihood that population growth in Israel will cease in the foreseeable future is extremely low. There is no way that such restrictive measures could be passed by the Knesset, because they contradict the social norms regarding nuclear families and absorption of new immigrants that are widespread among a vast majority of the Israeli public and its political representatives. We must therefore prepare for relatively rapid continued population growth, even if it will moderate over time.

A variable which should be related to much more seriously, at least in the medium term, is the dispersal of population in Israel’s southern territory and to a certain extent its north, in contrast with the present concentration in the center. The existing national master plans take these alternatives into account to some extent, but much more vigorous and consistent treatment of these issues is needed. The rate of infrastructure development in Israel—such as beds in hospitals, kilometers of highways and railway tracks, building of new classrooms—cannot be slower than the rate of annual population growth, but in practice this is the case. It should also be noted that a deep political crisis that causes a sharp decrease in the level of public trust in leadership and government—like that which occurred in Israel in 2023—may cause a severe change in the core consensus around shared existence, with real implications on demography similar to those described in the paradox above.

If massive aliya to Israel is unlikely and subject to the scenario of avoiding major outward migration from Israel, then continued population growth in Israel will be tied to the two challenges of defining the state’s Jewish and democratic character. Major additional growth is likely to come from populations less focused on the Jewish character of the state, such as the Arab-Palestinian sector on the one hand, and on its democratic character, such as the haredi sector on the other hand. In light of employment patterns of these population sectors, the maintenance of an attractive, sophisticated and self-supporting economy is uncertain. These population sectors have remained marginal until now in economic production and security efforts. One of the roots of this problem is the existence of four separate publicly funded education streams in Israel. These serve to preserve separate moral and social norms, a different national ethos, different training levels, orientations towards employment and above all, seeds of mutual suspicion all the way to hatred between graduates of different streams. Without an agreed-upon solution of a core curriculum along with maximum freedom of expression to each school regarding its ideological path, the concept of a state is emptied of its content, and the education system serves as a tool for preserving and widening disparities between the different population sectors.

It is essential to maintain a measure of civic dialog amongst the various population sectors, while cultivating common ground, reducing socioeconomic gaps, encouraging involvement and concern for the needs of all, and ensuring that all contribute their share to the state’s development. In the specific context of existing demographic disparities, an important goal is maintaining the current age structure of children, adults and the elderly. The present balance in Israel is relatively comfortable, as a foundation for future demographic stability as well, in comparison to other developed countries. It is also essential to remember that Diaspora Jewry—which is a hidden factor and a potential partner for the development of Israeli society—is not structured as a copy of Israeli society and does not reflect its party-political structure. A true dialog between Israel and world Jewry requires internalizing and considering in Israel the many ideas and concepts of Jewish identity and peoplehood, which are accepted and even dominant abroad.