Publications

A Special Publication in cooperation between the INSS, the Institute for the Study of Intelligence Methodology at the Israel Intelligence Heritage Commemoration Center (IICC), and the Ministry of Intelligence. January 4, 2024

Over the past decade, governments, private companies, expert communities, and civil society organizations around the world have invested significant efforts and resources to understand and address subversive malign activities conducted by foreign states and non-state actors. Research and policy-related initiatives and legal actions undertaken during this period have exposed significant conceptual and normative gaps not only between democratic countries and countries at odds with human rights, but among like-minded democracies as well.

When examining the state of contemporary political, professional, and academic discourse on foreign influence and interference, it quickly becomes clear that there is a significant discrepancy between different definitions and approaches. These differences can be found on all levels of analysis and conceptualization: from basic understanding of what foreign influence and interference are, how they are conducted, and what they do, to strategic frameworks for how foreign influence and interference can be used to serve political aims.

The purpose of this article is threefold. First, it reviews the state of the contemporary debate. Starting with the review of existing strategic frameworks, it focuses on the main trends in existing denotative approaches to foreign influence and interference. Second, it critically analyzes existing concepts and approaches, identifying common gaps and misconceptualizations. Finally, based on the review and critical analysis, it builds the conceptual framework by constructing separate definitions of foreign influence and foreign interference, thus offering a better understanding of the difference between these two phenomena.

Part I: The State of the Debate

Existing Strategic Frameworks for Foreign Influence and Interference

The principle of non-intervention into internal affairs of other states has a long history.[1] Article 2.4 of the UN Charter clearly states that “all Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.”[2] However, over the past decade, Western academic, professional, and policy-relevant discourse has been shaped by three new conceptual frameworks intended to describe foreign influence and interference below the threshold of open military confrontation: “hybrid warfare/threats,” “gray zone,” and “Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI).”

Hybrid Warfare: The idea of hybrid warfare/threats has a long and complicated conceptual history, during which the definition of concept (what it is), as well as what it entails (what it does), has been repeatedly adjusted and reconceptualized.[3] Initially introduced in the US, the hybrid warfare framework gained its popularity in Europe after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea.[4] While the concept has no definitive definition, it is possible to group all existing approaches into two main interconnected clusters. The first cluster consists of different definitions prevalent in military discourse. The best example of these approaches is the definition adopted by the Multinational Capability Development Campaign (MCDC): “Hybrid warfare is the synchronized use of multiple instruments of power tailored to specific vulnerabilities across the full spectrum of societal functions to achieve synergetic effects.”[5] The second cluster includes definitions used by different European political institutions. The best example of these approaches is the definition introduced by the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE), according to which “the term hybrid threat refers to an action conducted by state or non-state actors, whose goal is to undermine or harm a target by influencing its decision-making at the local, regional, state or institutional level.”[6]

Gray Zone: While the concept of hybrid warfare/threats has dominated the discourse in Europe, the concept of gray zone has gained its popularity in the US. Led by the US Army, especially the special forces community, the concept of gray zone became increasingly prevalent in the mid-2010s.[7] Similar to hybrid warfare, there is no definitive definition of gray zone. After assessing different existing definitions, researchers at the RAND Corporation concluded that “the gray zone is an operational space between peace and war, involving coercive actions to change the status quo below a threshold that, in most cases, would prompt a conventional military response, often by blurring the line between military and nonmilitary actions and the attribution for events.”[8] This concept shares many core assumptions with the concept of the “campaign between wars,” independently developed by Israeli strategists over the last decade.[9] As Amos Yadlin and Assaf Orion argue, the core principle of the campaign between wars is “to avoid escalation and conduct operations under the war threshold,” by “reducing the enemy’s sense of urgency to react with an escalatory response.”[10]

Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI): While the concepts of hybrid warfare/threats and gray zone originate from political-military discourse, the FIMI framework has entirely civilian roots. It was proposed in 2021 by the European External Action Service (EEAS) in response to the 2020 call by the EU Commission for a further refinement of the conceptual frameworks around disinformation.[11] Adopted by different strategic documents, such as the 2022 Strategic Compass for Security and Defense[12] and the 2022 Council Conclusions on FIMI,[13] the concept has become a term of art across the EU professional and policy-relevant discourse. According to EEAS, FIMI describes “a mostly non-illegal pattern of behavior that threatens or has the potential to negatively impact values, procedures, and political processes. Such activity is manipulative in character, conducted in an intentional and coordinated manner, by state or non-state actors, including their proxies inside and outside of their own territory.”[14]

Existing Approaches to Foreign Influence and Interference

Following the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the controversies surrounding the 2016 presidential elections in the United States, the terms “foreign influence” and “foreign interference” assumed center stage in discussions among different governments, private companies, expert communities, and civil society. While there is little agreement on what these two phenomena entail, a review of many definitions and approaches proposed in the last several years allows identification of five main conceptual trends in the discourse about foreign influence and interference.

Influence versus Interference: Existing approaches adopted by governments and academia vary in their understanding of the difference between foreign influence and foreign interference. The approach adopted by the Australian government clearly distinguishes between influence and interference. While it seeks to counter foreign interference, which is “coercive, corrupting, deceptive or clandestine, and contrary to Australia’s sovereignty, values and national interests,” it “is not concerned with foreign influence activity that is open and transparent and that respects our people, society and systems.”[15] The EU stance represents an opposite example, where the official approach does not recognize the difference between foreign influence and foreign interference, using them interchangeably.[16] Moreover, they rarely provide clear definitions of foreign influence or interference; instead they offer a nonexclusive list of examples of activities that can be considered as foreign influence or interference and avoid formal definition altogether. Finally, they frequently include different negative adjectives, such as “malign,”[17] “malicious,”[18] or “manipulative.”[19]

Domain of Influence and Interference: When discussing foreign influence and interference, existing approaches vary in their focus on the domain within which these activities take place. While there is general agreement that these activities pursue political goals by interfering, subverting, or detrimentally affecting the established democratic processes, approaches differ in their emphasis on the domains in which these activities can be conducted. On the one side of the spectrum, there are approaches that focus exclusively on the information domain as the main field of foreign interference, addressing disinformation and social media campaigns, relevant cyber activities, fake news, and data misuse and manipulation.[20] In contrast, there are approaches that take a more holistic view that incorporates not only information activities, but also other actions intended to interfere in established political processes, such as trade and investment, corruption, migration exploitation, and manipulation of international organizations.[21] In other words, while some approaches to foreign influence and interference take a more holistic view and include everything that foreign actors do, others focus exclusively on information, disregarding other potential domains of influence.

Intent: Many existing approaches tie their understanding of foreign influence and interference to the issue of intent. Some approach this question in an explicit way, referring to intent as a determining element in foreign interference. For example, the US Department of Homeland Security defines foreign interference as “actions…designed to sow discord, manipulate public discourse, discredit the electoral system…for the purpose of undermining the interests of the United States and its allies.”[22] On the other hand, others approach the question of intent implicitly, simply referring to foreign influence and interference as “hostile,” “malicious,” “malign,” or “manipulative.” While there is little consensus on the strategic nature of this intent beyond the maligned tactical action, the non-definitive list of most frequently mentioned include: to coerce, undermine, subvert, manipulate, and disrupt established democratic processes and/or amplify societal divisions.

Transparency: Some existing approaches explicitly refer to the question of transparency as a determinant in defining foreign influence and interference, when “the former is open and honest, whereas the latter is covert and/or deceptive.”[23] Other approaches refer to this question implicitly, by approaching any foreign interference or influence as “covert,” “deceptive,” or “clandestine.”[24] Many existing approaches assume that transparency implies legitimacy, or suggest that the question of transparency is the main difference between foreign influence and interference, as “foreign influence is open and honest whereas foreign interference is clandestine and deceptive.”[25]

Legitimacy: Defining foreign influence and interference, existing approaches vary in their use of different dichotomies to discuss legitimacy. Most frequently used frameworks are “legitimate vs. illegitimate,” “acceptable vs. unacceptable,” “legal vs. illegal.” Some approaches adopt these frameworks explicitly, acknowledging the possibility of legitimate/acceptable/legal versus illegitimate/unacceptable/illegal foreign influence and interference. For example, the EEAS uses the term “non-illegal.”[26] Most approaches, however, discuss these distinctions implicitly, focusing exclusively on foreign influence and interference as something illegitimate/unacceptable/illegal. Both, however, tend to adopt dichotomous frameworks of ‘either … or’ and rarely see these distinctions as a continuum.

Part II: Analysis

Analysis of Hybrid Warfare/Threats and Gray Zone

While these two strategic frameworks were developed independently, according to many experts they share many common attributes.[27] Both essentially describe a mix of hostile means and methods intended to achieve desired political aims without escalating to direct armed military confrontation. In other words, both describe a strategic approach to malign foreign influence short of war.

Since the comeback of the great power competition in the early 2010s, the Western strategic vocabulary has been tainted by a large number of different terms denoting more or less the same activity – hostile international relations between political actors short of kinetic application of force. Hybrid warfare/threats and gray zone are good examples of poorly constructed strategic frameworks that lack conceptual rigor.[28] The main conceptual flaw of these frameworks is their attempt to offer an objective definition to a practice in international relations. However, no Western political or military actor would acknowledge that they conduct hybrid or gray activities.[29] Conceptualized as a set of activities pursued only by adversaries, these frameworks fail to recognize their inherent subjectivity that ultimately undermines their rigor. For example, if hybrid warfare is “the synchronized use of multiple instruments of power tailored to specific vulnerabilities across the full spectrum of societal functions to achieve synergetic effects,”[30] then activities of any political actor (from the most liberal democracy to the most autocratic regime) involved in a non-military confrontation can be characterized as hybrid warfare. If gray zone is “an operational space between peace and war, involving coercive actions to change the status quo below a threshold that, in most cases, would prompt a conventional military response,” then it is not only China that operates in the gray zone in the South China Sea,[31] but also NATO, as it attempts to coerce the Kremlin by means and methods that would not prompt Russian military response against NATO.

Analysis of Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI)

While hybrid warfare/threats and gray zone were intended to provide an overarching strategic framework for malign foreign influence, they came with many conceptual caveats,[32] encouraging experts and policymakers to focus on foreign influence and interference as concepts on their own. The FIMI framework has been one of the main outcomes of this shift in focus. Since the framework is relatively new (introduced in 2021), its conceptual rigor has not been subjected yet to an extensive critical assessment by the expert community. However, its exclusive focus on interference in information domain already undermines its potential as a strategic framework. In other words, since FIMI focuses on information interference only, it ultimately fails to recognize the holistic nature of foreign influence and interference that interweaves political, economic, informational, diplomatic, financial, and other activities in international relations. According to EEAS, FIMI comes to describe what is “often labeled as disinformation,”[33] and, therefore, by its very definition, it cannot offer a strategic framework for understanding foreign influence and interference in international relations.

Analysis of Conceptualizations of Foreign Influence and Interference

The exisiting strategic frameworks not only try to reinvent the wheel by offering new conceptual frameworks for something that has always been common practice in international relations, but they also focus exclusively on influence that is perceived as hostile. This leads to the failure of these frameworks to recognize that influence in international relations can be perceived in ways positive and negative and its perceived hostility is subjective to the influenced. In other words, similar to many Western countries that perceive Russian hybrid warfare/threats as hostile influence, Russia can perceive Western soft power as a hostile influence on Russia.

An analysis of contemporary scholarly and professional discourse on foreign influence and interference shows that very little effort has been invested in trying to understand and define what these phenomena are. Moreover, foreign influence and interference have been commonly defined and discussed in a negative way (with Australia being a helpful exception), as a set of threats or activities that need to be countered or eliminated, failing to acknowledge that under certain circumstances foreign influence can be welcomed. Moreover, many existing approaches and definitions fail to conceptually recognize the inherent difference between foreign influence and foreign interference, using the terms influence and interference interchangeably.

On the one hand, in their attempts to define foreign influence and interference, existing approaches operate with relevant characteristics, such as transparency or legality. On the other hand, due to the exclusive focus on foreign influence as something conducted by malign actors with hostile intent, there is much confusion and misunderstanding what foreign influence and interference are, what they do, and how they can be addressed.

One of the main conceptual drawbacks of the existing approaches to foreign influence is their failure to recognize that influence is not a goal in and of itself, but the means in international relations to achieve a political goal. Arguably, all interactions (both deeds and words) between states (in all domains of national power: political, information, military, economy, and others) are the means of influence in pursuit of political goals in international relations.

Part III: The Influencer and the Influenced in Foreign Influence and Interference

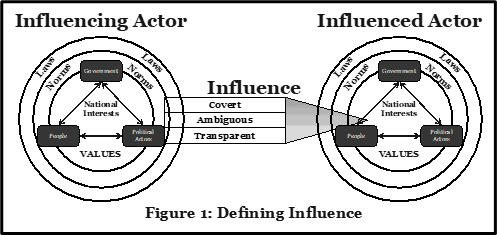

To define foreign influence, it is important to focus on three main aspects. First, an influencing actor formulates the intent of its influence in the context of its national interests (constructed through interaction between the government, different domestic political actors and institutions, and the people) and shaped by its national values (Figure 1).[34] In most of the cases the true intent of the influencing actor will be unknown to the influenced actor. Even in the cases when foreign influence is invited and welcome, its true intent remains unknown to the inviting actor. Therefore, trying to tie the definition of influence (or interference) to the nature of influencing actor’s intent is misleading and counterproductive.

Second, the question of transparency is determined by the influencing actor, not the influenced. Since the true intent of influence is known only to the influencing actor, it is he who decides whether the influence exercised by him will be transparent, ambiguous, or covert. Since influence is not a goal, but the means in international relations to achieve a political goal, the transparency of the actions conducted in pursuit of influence is shaped by the strategic goals (intent) behind these actions. For example, a foreign investment in national infrastructure of the influenced actor can be either a transparent influence (investment in pursuit of transparent and openly declared goals), or it can be covert (investment in pursuit of covert – other than openly declared – goals), or it can be ambiguous (investment that has a potential to be used for other than openly declared goals).

Finally, influence is characterized (as hostile or otherwise) by the influenced actor in the context of its national interests and values, as well as norms and laws intended to shape and protect them. In other words, the issue of hostility is judged by the influenced actor’s perception of this influence, and the same influence driven by same intent can be perceived differently by different influenced actors.

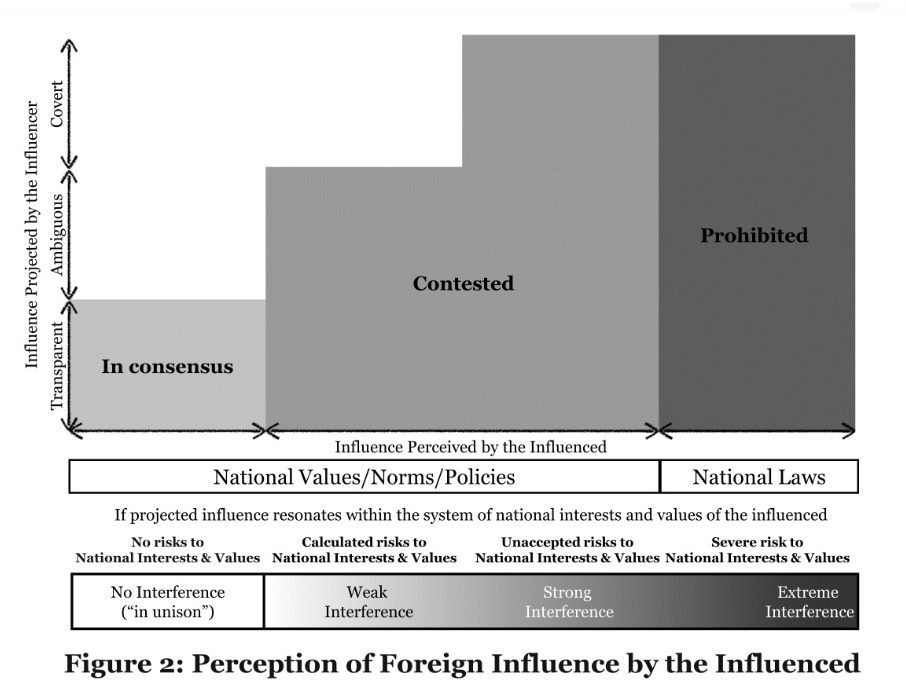

The influence can be perceived by the influenced in three different ways. First, it can be perceived as welcomed, as it acts in consensus with national norms and values of the influenced actor. Second, it can be perceived as prohibited, as it acts against the existing national laws of the influenced actor. And finally, the nature of influence can be contested, as it is neither implicitly in consensus with the influenced actor’s national norms and values nor explicitly prohibited by its legal system. Sometimes, contested influence can be tolerated in the name of values and interests (e.g., freedom of speech, human rights, etc.). On other occasions, it can be perceived as unlawful and requiring new relevant legislation. The way influence is perceived by the influenced actor will be shaped by its national norms, policies, and laws (Figure 2).

The perceived nature of influence depends more on the influenced actor’s internal elements, rather than on the issue of transparency (or lack thereof). Since the issue of transparency is controlled by the influencing actor, any influence (transparent or not) will be judged by the influenced actor in the context of its values/norms/policies and laws. For example, a transparent influence can be perceived by the influenced as in consensus, contested, or prohibited, depending on its national values/norms/policies and laws. An ambiguous influence would not be welcome; however, it can still be perceived as contested or prohibited. A covert influence will usually fall in the area of already prohibited or something unlawful that requires new legislation.

Most of the existing approaches try to address the area of contested influence, as its acceptability, tolerability, and legality is contested in the context of the existing values/norms/policies and laws. The problem with these approaches, however, is that their exclusive focus on this particular type of influence (combined with the failure to acknowledge the existence of other types) undermines their conceptual rigor.

The final limitation of the majority of existing approaches is their confusion between foreign influence and foreign interference, to an extent that sometimes these terms are used interchangeably. Influence is the means in international relations to achieve a political goal. Foreign influence can achieve these goals only if it resonates within the system of the national interests and values of the influenced. Without this resonance, foreign influence is meaningless as it fails to interact with the influenced actor in any way (positive or negative). For example, an attempt to influence an Amazonian tribe through information about the Second World War would generate no resonance, as the peoples of this tribe simply have no knowledge of this war.

Since the way foreign influence is perceived and the type of resonance it can create are defined by the national interests and values of the influenced actor, there is a strong correlation between them. The resonance created by foreign influence in consensus would create no interference, as it would act “in unison” with the existing national interests and values. However, as the risk created by this resonance to these interests and values increases, the more interference it creates (Figure 2).

Conclusion: Defining Foreign Influence and Interference

Foreign influence is a core element of international relations. International actors have always sought to influence each other’s affairs and decision making in pursuit of their political goal. In other words, foreign influence encompasses any type of interaction between two political actors – whether it is honest cooperation based on shared democratic values, or an act of war. After all, war is “an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will,”[35] i.e., influence. Foreign influence has always been the fundamental means in international relations, and therefore, there is no need for new conceptual strategic frameworks. Instead, it should be seen for what it has always been: a deployment of different sources of national power (diplomatic, information, military, economic, financial, religious, etc.) by one international actor to influence another in pursuit of a political goal.

Following this definition of foreign influence, it is possible to define foreign interference as a particular type of foreign influence: foreign influence can be characterized as foreign interference when the deployment of different sources of national power (diplomatic, information, military, economic, financial, religious, etc.) by one international actor to influence another is perceived by the latter as in contradiction with his values, norms, or laws.

___________________

[*] This article is part of a forthcoming memorandum on the strategic challenge of foreign influence and intervention. The memorandum includes articles that examine the challenge from the perspective pf adversaries (e.g., Russia, Iran, and China), and deals with the nature of the influence (including via human influence agents and in the economic and academic worlds). The challenge will be examined with respect to routine times, as well as with respect to times of disruptions to democratic processes, deepened social rifts, election campaigns, and war. The articles will reflect a connection between systemic insights and the policy necessary in Israel and Western states. The memorandum is the product of collaboration between the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) and the Institute for the Study of Intelligence Methodology at the Israel Intelligence Heritage & Commemoration Center (IICC), with the assistance of the Ministry of Intelligence.

[1] Michael Wood, “Non-Intervention (Non-interference in domestic affairs),” Princeton University, https://pesd.princeton.edu/node/551

[2] United Nations, United Nations Charter, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/full-text

[3] Ofer Fridman, Russian “Hybrid Warfare”: Resurgence and Politicization (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022).

[4] Ibid.

[5] The Multinational Capability Development Campaign (MCDC), Countering Hybrid Warfare (2019), p. 12, http://tinyurl.com/27zwnsc3

[6] The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE), “Hybrid Threat as a Concept,” https://www.hybridcoe.fi/hybrid-threats-as-a-phenomenon/

[7] Donald Stoker and Craig Whiteside, “Blurred Lines: Gray-Zone Conflict and Hybrid War: Two Failures of American Strategic Thinking,” Naval War College Review, 73, 1, (2020): 13-48.

[8] Lyle J. Morris, Michael J. Mazarr, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Stephanie Pezard, Anika Binnendijk, and Marta Kepe, Gaining Competitive Advantage in the Gray Zone: Response Options for Coercive Aggression Below the Threshold of Major War (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019), pp. 7-8.

[9] Shai Shabtai, “The Concept of the Campaign between Wars,” Maarachot, No. 445 (2012): 24-27 [in Hebrew].

[10] Amos Yadlin and Assaf Orion, ‘The Campaign between Wars: Faster, Higher, Fiercer?’ INSS Insight No. 1209, (2019), http://tinyurl.com/3j2hn756

[11] The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) and the European External Action Service (EEAS), Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) and Cybersecurity – Threat Landscape, December 2022, p. 4, http://tinyurl.com/yjxwuf3w

[12] Council of the European Union, 2022 Strategic Compass for Security and Defence, March 21, 2022, http://tinyurl.com/2732xzsd

[13] Council of the European Union, Council Conclusion on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI), July 18, 2022, http://tinyurl.com/jyk8d4ye

[14] The European External Action Service (EEAS), 1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats, February 2023, p. 4, http://tinyurl.com/ycyfcw9b

[15] Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs, Defining Foreign Interference, http://tinyurl.com/t4c5c29a

[16] European Parliament, Foreign Interference in All Democratic Processes in the European Union, March 9, 2022, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0064_EN.pdf

[17] For example: G7, Charlevoix Commitment on Defending Democracy from Foreign Threats, June 9, 2018, http://tinyurl.com/mt7pb5e7

[18] For example: European Commission, Securing Free and Fair European Elections, September 12, 2018, http://tinyurl.com/ystkhc57

[19] For example: Council of the European Union, Complementary Efforts to Enhance Resilience and Counter Hybrid Threats, December 10, 2019, http://tinyurl.com/78emmdb2

[20] For example, The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) and the European External Action Service (EEAS), Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) and Cybersecurity – Threat Landscape; The European External Action Service (EEAS), 1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats.

[21] For example: Katherine Mansted, “The Domestic Security Greyzone: Navigating the Space Between Foreign Influence and Foreign Interference,” National Security College Occasional Paper, Australian National University, 2021; US Department of Homeland Security, “Foreign Interference Taxonomy,” July 2018, http://tinyurl.com/5h6eem7w

[22] US Department of Homeland Security, Foreign Interference Taxonomy (emphasis added).

[23] Kate Jones, “Legal Loopholes and Risk of Foreign Interference,” In-Depth Analysis requested by the ING2 Special Committee at the European Parliament, January 2023, p. 21, http://tinyurl.com/y8hhku3b

[24] For example: Australian Department of Home Affairs, Countering Foreign Interference, January 27, 2022, http://tinyurl.com/mrfrjp2x

[25] Jones, “In-Depth Analysis: Legal loopholes and the Risk of Foreign Interference,” p. 21.

[26] The European External Action Service (EEAS), 1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats.

[27] For example, Frank Hoffman, “Examining Complex Forms of Conflict: Gray Zone and Hybrid Challenges,” Prism, 7, 4(2018): 31-47; Stoker and Whiteside, “Blurred Lines,” Fridman, Russian “Hybrid Warfare.”

[28] Vladimir Rauta, “A Conceptual Critique of Remote Warfare,” Defence Studies, 21, 4(2021): 545-72; Stoker and Whiteside, “Blurred Lines”; Fridman, Russian “Hybrid Warfare.”

[29] Ofer Fridman, “Afterword to Paperback Edition: Moving Beyond Hybrid Warfare,” in Fridman, Russian “Hybrid Warfare.”

[30] The Multinational Capability Development Campaign (MCDC), Countering Hybrid Warfare, p. 12

[31] Peter Layton, “Responding to China’s Unending Grey-Zone Prodding,” RUSI Commentary, August 11, 2021, http://tinyurl.com/mrm5nspr

[32] For example, Fridman, Russian “Hybrid Warfare”; Stoker and Whiteside, “Blurred Lines”; Hoffman, “Examining Complex Forms of Conflict.”

[33] The European External Action Service (EEAS), 2021 StratCom Activity Report, 2021, p. 2, http://tinyurl.com/w6abcryk

[34] While the conceptualization here is between states (i.e., national interests, government, people, etc.), it can be easily translated to non-state actors (i.e., actor’s interests, actor’s leadership, actor’s norms and values, etc.).

[35] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 13.