Strategic Assessment

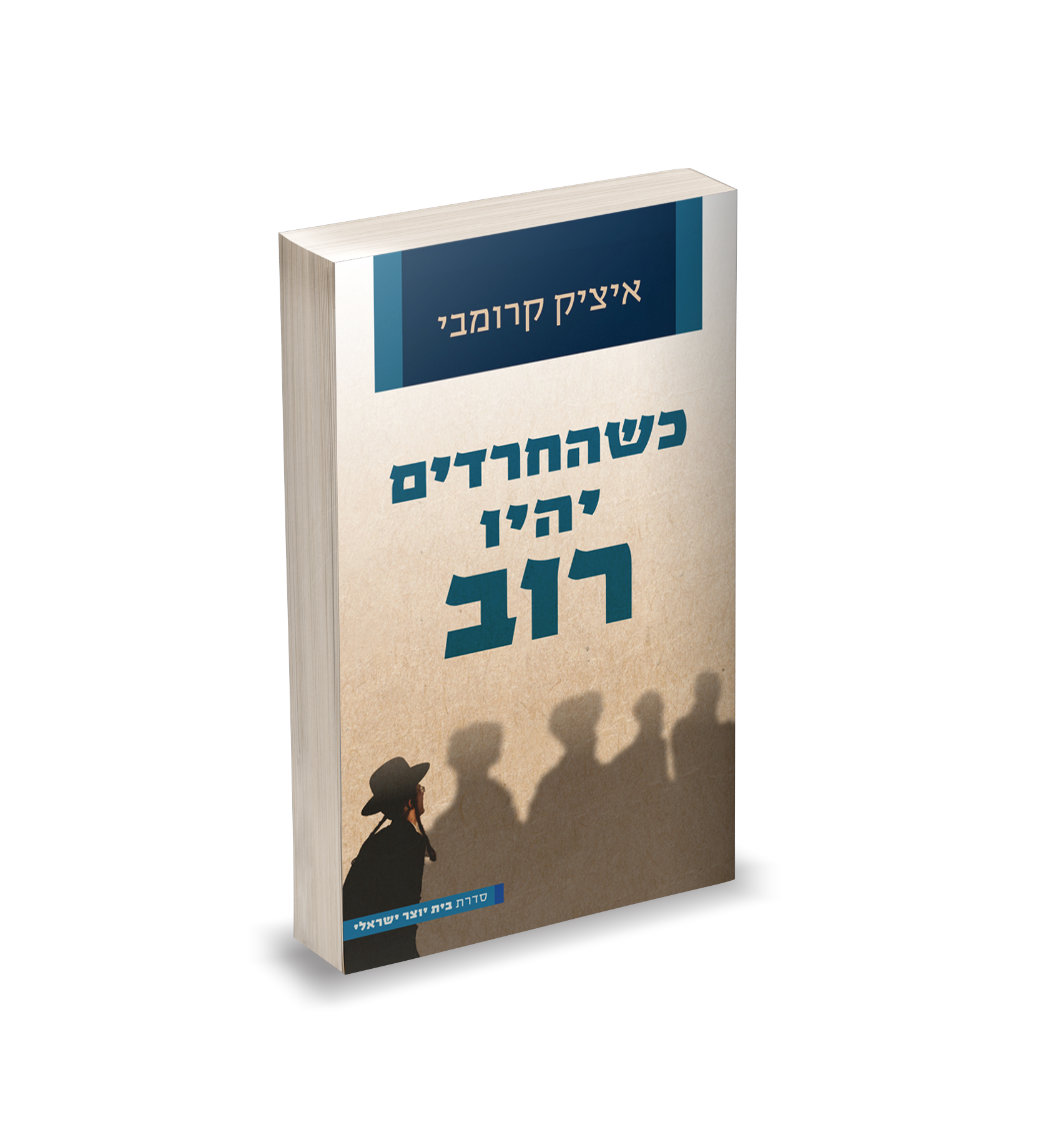

- Book: When the Ultra-Orthodox Become the Majority

- By: Yitzik Crombie

- Publisher: Miskal (Yediot Books), Beit Yotzer Israel Series

- Year: 2022

- pp: 350 pages [in Hebrew]

The ultra-Orthodox ideology of segregation from the State of Israel and its symbols and how the state addresses this phenomenon may propel Israel to the brink of an existential crisis. The Central Bureau of Statistics estimates that by 2065 every fourth Israeli citizen will be ultra-Orthodox. As long as the non-ultra-Orthodox majority actively wishes to have the ultra-Orthodox minority assimilated, or at least integrated, into the general population, the ultra-Orthodox will regard such attempts as a threat to their symbolic existence. This fact creates a mutual sense of distance, alienation, and contempt, which maintains and perpetuates barriers to ultra-Orthodox integration, and even increases their isolationism.

In When the Ultra-Orthodox Become the Majority, Yitzik Crombie, a social and hi-tech entrepreneur, reveals just how much this subject is close to his heart. The book, written in plain language and a friendly and heartfelt tone, is divided into ten chapters, covering four subjects related to the ultra-Orthodox sector: ideology, education, conscription into the IDF, and the economy. Including many important points, the book skillfully presents a magnificent and rare composition, combining current academic research and words of Torah, religious thoughts, stories of Jewish sages, and historical reviews. All these are accompanied by anecdotes from the author’s personal experience, gained through his activities as a social entrepreneur involved in both the secular and ultra-Orthodox worlds.

This book is a must on every Israeli bookshelf, especially among those dealing with the study of Israeli or Jewish society. Besides its theoretical contribution, it provides a singular reading experience. Few authors are capable of conveying the sense that they are actually present in the same room with the readers, reaching out to them and leading them on a personal, pleasant, and enriching tour through the contents of a book, and Crombie is definitely one of them. He presents the painful truth as it actually is, honestly attempting to unfold the scene in a balanced and unbiased manner, yet with a degree of charm and grace, softening the reality with humorous and light references. Thus, the final product allows ultra-Orthodox and non-ultra-Orthodox readers alike to sit back, read, identify, and understand.

Perhaps two short excerpts concerning the drafting of the ultra-Orthodox best reflect the spirit of the entire book:

19-year-old Moishe is long weary of studying, and running about on dunes with a rifle on his shoulder sounds like a much more thrilling experience. So Moishe arrives at the IDF Induction Center (“bakum”) and sits down in front of a female soldier...Moishe is well taken care of. He serves with fellow men and eats glatt kosher food in the mess hall, all in accordance with law and custom. And then comes Memorial Day, and a female soldier goes on stage, preparing to sing. Oy vey! A woman’s voice! The ultra-Orthodox soldier is trapped between his duty to take part in the ceremony, and halacha [Jewish law]...If Moishe is smart, and his commander is willing to turn a blind eye, a short visit to the restroom may be a good solution to those five critical minutes. Yet at events of larger scale, especially those of high public profile, such an encounter may prove disastrous for Moishe and damage the trust between the army and the ultra-Orthodox. (pp. 216-217)

The ultra-Orthodox have no problem with matters of spirit, values, and ethics, as long as they are determined by God and rabbinical authority—and not by the drafter of the IDF Code of Ethics, Prof. Asa Kasher. However, the spirit of the IDF, though imbibing from the generations of Jewish tradition, is light years away from the spirit of ultra-Orthodox Judaism, and when the IDF, being a secular army, defines these values, the ultra-Orthodox can by no means identify with them...Just as a secular person would not educate his son according to the values and ethics of the Ponevezh yeshiva, the ultra-Orthodox are afraid to send their children to the IDF’s melting pot, where they might absorb Israeli-secular values. (pp. 219-221)

Alongside its many strengths, the book seems to lack adequate clarity on some issues and includes some lack of precision, for example, regarding ultra-Orthodox education. There is immense importance attached to this issue, regarded by many as a key to a successful integration of the ultra-Orthodox in Israeli society, and it necessarily extends to other issues, such as isolationism, military service, and the integration in the workforce.

The belief that civics, math, and English classes in elementary school would necessarily prompt the ultra-Orthodox to rush to higher education, the IDF, and the workforce embodies a certain degree of condescension and a sense of disrespect toward ultra-Orthodox ideology and people. Although this premise has not yet been validated or even empirically proven, it is widespread among many people and entities, which makes the discourse on this issue rather inaccurate, and even erroneous at times. When reading the chapter dealing with education, I sometimes had the impression that this conception had infiltrated certain parts of the book, causing one to ignore different methodological facts.

For example, the book cites, inter alia, the poor achievements of ultra-Orthodox schools in comparative exams (Meitzav) (p. 119), failing to mention the fact that no exempt institutions take part in these exams. Paradoxically, it is ultra-Orthodox schools that wish to teach their students core subjects that participate in the Meitzav exams. These institutions enjoy generous funding, and their teaching staff meet the requirements of the Ministry of Education. In the absence of an alternative explanation to the relatively poor achievements of these schools, it would seem that the learning capabilities of the students sent by their parents to institutions that teach core subjects are not high enough.

The issue of the professional training of the ultra-Orthodox has significance for the future of the State of Israel. According to the State Comptroller’s report of 2019, 76 percent of ultra-Orthodox students are likely to drop out of their studies—a cause for concern for the country’s future. Many tend to attribute these dropout rates primarily to difficulties resulting from the lack of core studies at elementary schools. Those propounding this view urge incentivizing ultra-Orthodox institutions to include core subjects within their curricula, mainly by imposing fines or various sanctions.

Yet surprisingly, some of the entities and individuals acting to implement core studies in ultra-Orthodox institutions specifically prevent the existence of culture-sensitive academic frameworks that would enable ultra-Orthodox men and women to study separately. Thus, while these entities state that their activities are intended to aid the integration of the ultra-Orthodox in the workforce, their actions work to the opposite effect. They seem to be unaware of the inherent contradiction within their activity, and they might also be assured that their course of action actually benefits the ultra-Orthodox and the general population. An example of this phenomenon can be found in Crombie’s reference to the Supreme Court’s approach toward integration of the ultra-Orthodox in higher education. While the Supreme Court has declared the importance of integrating the ultra-Orthodox in higher education, it has imposed many restrictions and in effect denies the ultra-Orthodox the possibility to obtain higher education and advanced academic degrees while preserving their identity and values. Crombie notes:

However, the Supreme Court has established several balancing factors in order to offset potential discrimination against female students who wish to study in mixed gender departments, as well as female lecturers wishing to teach courses intended for men. It has also been determined that separate programs will be offered during B.A. studies, but not for advanced degrees...During the deliberations, the justices claimed that segregated courses harm the principle of equality to a certain extent, but ruled that they are “reasonably proportionate”... and that the purpose of the segregation is to allow better integration of ultra-Orthodox men and women in higher education and the workforce, which constitutes an interest of individuals as well as Israeli society at large.

The Court’s ruling injects a new element. Contrary to the conception that regards segregation as a basic right of students, as established by law in 2007, the Supreme Court “apologized” for having to allow segregation and cede the equality principle, as segregation serves an important purpose—integrating the ultra-Orthodox in the academia...This glass ceiling blocks many ultra-Orthodox from even considering academic studies, since they realize that the purpose is to integrate them in the secular society and change their way of life. Higher education does not recognize the right of the ultra-Orthodox to study according to their lifestyle and religious principles, keeping them away (pp. 176-177).

Critical studies regarding culture (acculturation) and relations between majority and minority groups have suggested repeatedly that research in this field is indeed psychologically biased. This bias causes researchers within the majority group to forget that the customs and values of the minority group are not necessarily wrong, and thus in turn they interpret the findings erroneously. Researchers may often, in good faith (or not), wrongfully rely on misleading information or misguided interpretations that have taken root with those who first shoot the arrow (core studies), and only then mark the target (advancement and integration of the ultra-Orthodox society). As long as no body of theoretical and empirical knowledge is built from the ground up by a diverse team of researchers that includes some who advocate core studies for the ultra-Orthodox, as well as some who oppose it, this field will be flawed and not be able to constitute an informative and reliable body of knowledge, based on reasonable, balanced facts. Given that, the few errors found in the book may be regarded as acceptable, since the author relied on misleading information that has come to be accepted over the years. This is especially true considering the author’s evident efforts to clarify and validate the information to the best of his ability.

In summary, Yitzik Crombie’s book is an excellent work that provides an enriching, detailed, and thoughtful glimpse into the complex relations between the State of Israel and the ultra-Orthodox population. Although this is an explosive issue that is close to the heart of most Israeli citizens, Crombie has managed to present it in a reader-friendly manner, providing readers with relevant, up-to-date, and comprehensive information that can prompt a paradigm shift and constructive curiosity in searching and identifying potential solutions that would secure a better future for the State of Israel.