Strategic Assessment

The tension between Cairo and Addis Ababa reached a boiling point in July 2020, when Ethiopia began filling the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam reservoir. This followed years of fruitless talks aimed at formulating understandings and months of accelerated discussions, including negotiations mediated by the United States and the African Union, which have thus far come to naught. For both sides this is a strategic, “existential” issue with practical and symbolic repercussions, which renders a compromise difficult. Israel has an interest in the sides reaching a diplomatic agreement, as it would increase stability in the region, advance constructive solutions to the water and energy crises of both countries, and prevent a regional arms race. However, involvement in this conflict at such a sensitive time could do Israel more harm than good; it is therefore best for it to remain neutral. At the same time, if understandings are reached between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan, Israel will be able to take part in the development of a Nile Basin regional framework.

Keywords: Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan, Israel, Renaissance Dam, Nile, water, energy

Background

In advance of the summer of 2020 (the rainy season in the region), Ethiopia announced that it was determined to begin filling the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) reservoir, even without an agreement with Egypt and Sudan. Indeed, satellite photos from July showed that the reservoir is being filled. After initial denials, Ethiopia admitted that it had begun filling it and that it had met its target for the current year, although it claims that this is a result of natural rainfall, and not necessarily a function of its activity. Consequently, Egypt is increasingly anxious about potential harm to the Blue Nile water supply, which accounts for 85 percent of all Nile water in its territory, and is Egypt’s near-exclusive water source. Cairo has repeated its demand that Ethiopia avoid unilaterally filling the dam, a position that is currently supported by Sudan and the US, which also decided to suspend part of its economic aid to Ethiopia.

The GERD is an enormous hydroelectric project, which Ethiopia began building in 2011, with billions of dollars invested in the venture. At the heart of the dispute between Ethiopia and Egypt stand several issues. On one level, there is the question of historic rights to Nile waters and the legal implications of such rights. On a practical level is the pace of filling the reservoir; Egypt wants a slow process of about 12 years, whereas Ethiopia would like an accelerated process of 3-4 years. Egypt is also demanding rules for filling the dam during drought years, commitments that will limit Ethiopia's right to build additional dams along the Blue Nile, and a mandatory mechanism for settling future disputes to deny Ethiopia exclusive control of the Nile waters.

The charged issue of the dam demonstrates the contradictory interests of both parties in water resource use, which is critical to the national security of the two countries. Ethiopia would like to build and fill the dam quickly, primarily for economic and infrastructural reasons. The dam is supposed to solve its electricity problem (65 percent of the population is not connected to the state electric grid) and improve potable water and irrigation supply. The dam is supposed to produce some 6,500 megawatts of electricity a year and allow regulation of the water flow of the Blue Nile for the benefit of agriculture, allowing Ethiopia to manage its frequent droughts better. The Ethiopian government is thus counting on the output of the dam and hoping that this will allow it to overcome major obstacles to national development of a country that has 110 million people and will probably surpass the 200 million mark by 2050. Egypt, which is also a country of over 100 million, already suffered from a severe water shortage prior to the filling of the dam. It refers to Ethiopia as a country with abundant water sources, questions the dam's ability to fulfill Addis Ababa's energy desires, and has warned about technical failures in its construction.

Over the last year, prior to the target date for filling the reservoir, Egypt worked vigorously in the diplomatic arena to pressure Ethiopia to sign an agreement to bridge the opposing interests of the two sides. It hoped that American mediation, and then UN Security Council intervention, would help soften the Ethiopian position. Ethiopia did in fact participate with Egypt and Sudan in US-sponsored talks between November 2019 and February 2020 (with World Bank involvement), but refused to accept the American formula, which it claimed was overtly pro-Egyptian. Egypt viewed Ethiopia's conduct as proof of Addis Ababa's obstinacy, and blamed it for deliberately torpedoing the agreement.

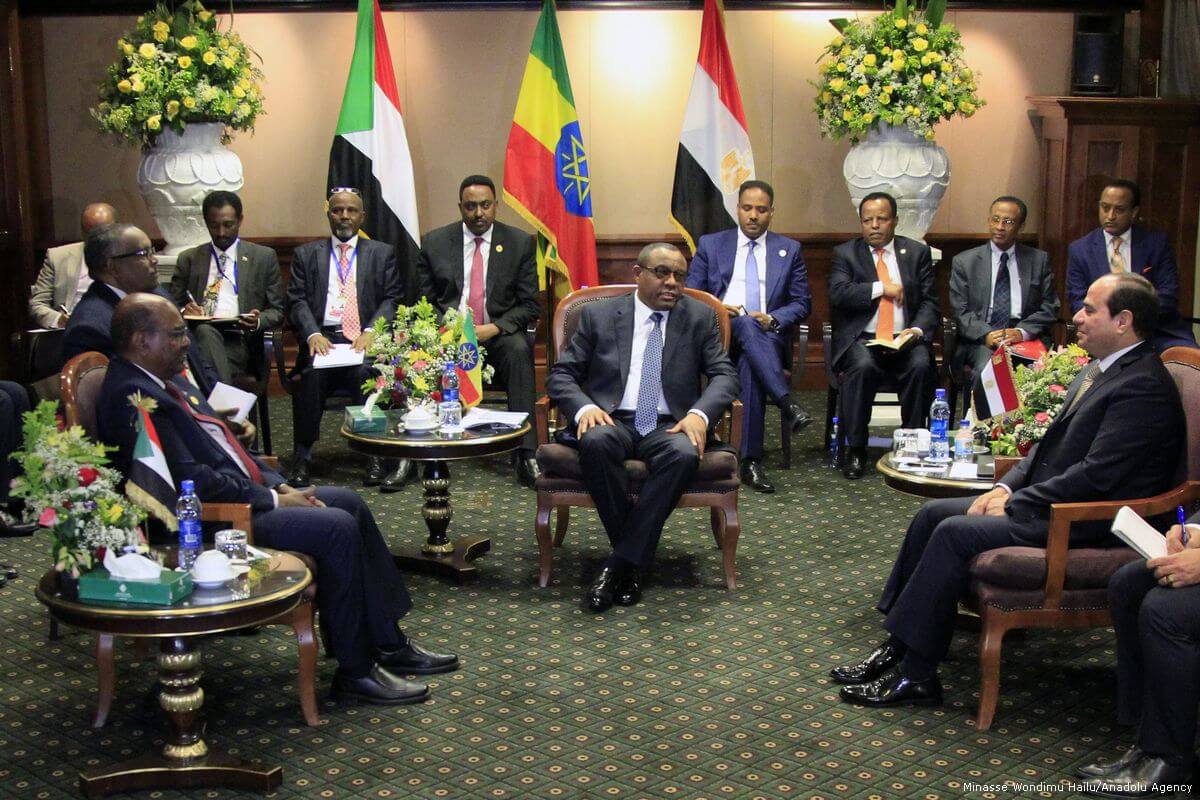

Ethiopia and several of its supporters in Africa (chiefly South Africa and Niger) opposed the Egyptian intention of involving the UN Security Council, claiming that that the organization has no right to decide on the matter. In June 2020, the tripartite talks moved to mediation by the African Union and its head, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who was acceptable to both the Egyptians and the Ethiopians. In spite of some progress, however, no breakthrough was achieved in these still ongoing talks. At the same time, Egypt had some success in bringing Sudan which had previously sided with Ethiopia closer to its position, but it is not yet clear whether that will have an impact on the Ethiopians.

In contrast to previous threats of military force against Ethiopia made by Egypt during the brief rule of the Muslim Brotherhood, current Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has put his trust in diplomatic channels as the most promising path for resolving the crisis. He has avoided explicit military threats against Ethiopia, although for their part, Ethiopian sources claimed they were ready to repel an Egyptian military threat. The Egyptian strategy focuses on applying international pressure on Ethiopia with an aim of postponing the filling of the dam or at least limiting the quantity of water filled, while warning that operating the dam is a violation of international law and endangers the security and peace of the continent.

Meanwhile Egypt is working to generate Arab and African pressure on Ethiopia. The Arab League published a statement calling on Ethiopia to refrain from filling the dam unilaterally, declaring that "Egypt and Sudan's water security are an integral component of Arab national security." In addition, Egypt is using its Gulf allies who have invested in Ethiopian economic projects to leverage their influence in Addis Ababa on its behalf, although it is unclear to what extent these allies are actually willing to promote Egyptian interests. Egypt is also trying to tighten its relations with Ethiopia's neighbors, including Eritrea, South Sudan, and Somalia, and is reportedly involved in covert activity aimed at applying more pressure on Addis Ababa, such as support for separatists in Ethiopia or parties hostile to it in neighboring countries.

At the same time, Egypt is calling to turn the dam crisis into an opportunity to create a regional partnership with Ethiopia and Sudan and promote cooperation and integration in the Nile Basin, which will address Ethiopian aspirations for accelerated economic, energy, and agricultural development, without harming Nile water supply. This vision coincides with the Egyptian attempt to become a regional energy hub, which includes ideas of connecting the energy networks of countries in the region to allow the sale of Egyptian electricity to Ethiopia, as well as the export of electricity produced by the Ethiopian dam to Egypt, and from there on to Europe, specifically to Cyprus and Greece. In an article from June 2020 in the establishment Egyptian daily al-Ahram, Dr. Mohamed Fayez Farhat, the head of Asia studies at the Egyptian Center for Strategic Studies, explained President el-Sisi's policy doctrine and the "carrots" offered to Ethiopia:

Regional resources can be a subject for cooperation rather than a subject for conflict. This is clearly reflected in the Egyptian positions on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and on Eastern Mediterranean gas. Regarding the former, el-Sisi still believes that the dam can be an opening for regional cooperation, so long as the parties commit to mutual non-harm; regarding the latter he has succeeded in building a network for regional cooperation on gas.

It is likely that Egypt will continue its intensive diplomatic activity in cooperation with Sudan, in an attempt to spur Ethiopia to reach an agreement with them that will place certain restrictions on dam operations. If these efforts fail and there is severe harm to Egyptian water resources, the probability of the use of force might increase.

However, the developments of the past year indicate that Ethiopia is in no rush to make significant concessions to Egypt. At the same time, the probability of Egyptian military counteraction is low at this stage. For one, such an attack is operatively challenging. Egypt has a strong army and its air force is ranked tenth in the world, but it has limited experience in complex long range attacks. The long-term effectiveness of such an operation is also limited, given that attacking the dam will not change the basic situation whereby Ethiopia controls the sources of the Blue Nile. Instead, it is likely that Egypt will continue its intensive diplomatic activity in cooperation with Sudan, in an attempt to spur Ethiopia to reach an agreement with them that will place certain restrictions on dam operations. If these efforts fail and there is severe harm to Egyptian water resources, the probability of the use of force might increase.

More than Just Water

Apart from disagreements over actual water use, the dam crisis is unfolding alongside a public controversy over competing historical narratives, which make it difficult for Egypt and Ethiopia to reach a middle ground in their disputes. The struggle over the dam has become a symbolic national affair in both countries that extends beyond material issues.

First, the sides disagree over the fundamental rights to use the Nile’s water. Egypt insists that it has the right to use most of the Nile's water and to veto actions that endanger its water allocation. It bases this claim on two agreements one signed in 1929 between Egypt and Great Britain, which represented its colonies in Africa (including Sudan), and a complementary agreement signed between Egypt and Sudan in 1959. The latter agreement granted Egypt rights to use the lion's share of river water (some 55.5 billion cubic meters) and gave Sudan a smaller allocation (18.5 billion cubic meters), while nothing was allocated to the other countries of the Nile Basin. Egypt, which sees itself as “the land of the Nile,” views its ownership of river water as inalienable "acquired rights" that are beyond question. This view is based on its historic link to the river and not merely on modern water allocation agreements: the Nile has been the pulse of Egypt since the days of the Pharaohs, its lifeline and an inseparable part of its identity. Cairo thus refuses to recognize the right of other countries in the Nile Basin to change the water use formula unilaterally, without Egyptian consent.

On the other hand, Ethiopia sees the agreements that underlie the Egyptian claims as colonial relics of the exploitation of Africa: agreements that were forced upon Ethiopia (which did not sign them) by Britain and Egypt. There were many years of hostility between Ethiopia and Egypt, which included Egyptian occupation of parts of Ethiopia during the 1870s and 1880s, and Ethiopia sees Egypt as a colonial power in itself. Ethiopian propaganda has called the dam "the last straw that breaks the colonial camel's back," while casting it alongside other anti-colonial achievements from Ethiopian history. Ethiopia thus principally opposes any infringement on its sovereignty in decision making and is determined to be released from restrictions on using a natural resource in its territory. Egypt for its part has also cultivated an anti-colonialist national ethos of liberation since the Egyptian revolution of 1952, and has repeatedly stated in response to Ethiopian criticisms that its right to the Nile is based on historic foundations that predate the colonial agreements.

Second, the Nile is a material issue in domestic politics in both countries. The el-Sisi regime is concerned that "surrendering" to Ethiopia on such a central matter will be perceived as a failure of the regime, as the Muslim Brotherhood is already criticizing its conciliatory approach and trying to manipulate the Egyptian public opinion against it. In an attempt to contain the damage to its image, spokesmen affiliated with the regime say that the filling of the dam should not be considered an Egyptian failure; on the contrary, the struggle has entered a new diplomatic phase in which Egypt will insist on UN Security Council intervention, and if necessary will use international arbitration. In this context some draw inspiration from the precedent of arbitration with Israel over control of Taba, which was decided in 1988 in favor of Egypt.

For Ethiopia the dam issue also has important political dimensions. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed strove to build his image as a proactive leader, reformer, and conflict resolver, and as the figure who will lead Ethiopia to the status of an African economic power. After resolving, at least on paper, the decades-long conflict with Eritrea, he is determined to get the dam up and running. The image factor has additional weight due to the domestic situation in Ethiopia, where the government must constantly celebrate its achievements due to the notable presence of separatist and opposition forces seeking to delegitimize the Ethiopian state. These domestic challenges are particularly evident this year, which was supposed to be an election year; Abiy claims that these will be free elections for the first time in Ethiopian history (though they have now been postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic). An additional source of domestic pressure on the Ethiopian government is that most of the funding for the dam came from selling government bonds to citizens, who are waiting impatiently for the return on their investment.

Implications for Israel: From Absolute Neutrality to Regional Partnership

The fight over the dam is a conflict between two strategically highly important countries for Israel. Egypt is the most populous Arab country and was the first to sign a peace agreement with it. As neighbors along Israel's southern border, the two countries share many interests in the fields of security, politics, and economy. Ethiopia is a central country in the African arena, especially in the Horn of Africa that lies adjacent to the Red Sea. It is undergoing rapid development processes, and herein lies its importance to Israel, which seeks to expand its political and economic ties on the continent. Israel also maintains close relations with the leaderships of both countries.

Israel has clearly decided to refrain from intervening in the dam crisis and is taking a neutral stance, advocating a "solution that would benefit both Egypt and Ethiopia." Israel certainly has a strong interest in the sides reaching a diplomatic agreement, which would increase stability within the two countries and in the region, advance constructive solutions to the respective water and energy crises, and prevent an arms race with the risk of escalation. At the same time, Israel could be drawn in, willingly or unwillingly, to this sensitive conflict. According to media reports in 2018, Egypt asked Israel to use its influence with Ethiopia regarding the dam. On the other hand, questionable sources linked Israel in 2019 to the establishment of an aerial defense system for the dam a report that sparked an uproar in Egypt and led the Israeli embassy in Egypt to issue an official denial.

So long as the conflict between Egypt and Ethiopia is unresolved, Israel should maintain absolute neutrality and refrain from any involvement in this volatile issue, for several reasons. First, this is a sensitive and complex issue in which two of its allies have legitimate justifications for their claims, and Israel has no interest in choosing a side. Second, the chances of successful Israeli mediation between the countries are low, as Israel has no relative advantage over other countries or international bodies that have tried to mediate and failed. Third, Israel's ability to offer practical solutions to the water shortage at the heart of the crisis is limited, given Egyptian resistance to normalization in this field, and even more so, given the severity of the challenge due to limited water resources in the region, demographic growth, worsening climate change, and the difficulty of raising the capital needed to desalinate water in the quantities required. Fourth, the neutral Israeli stance on the dam is consistent with its preference not to make a legal decision in the historic and religious conflict between the Egyptian Coptic Church and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church over the control of Deir es-Sultan in the Old City of Jerusalem.

Furthermore, involvement in this conflict entails the risk of harming Israel's image in Egypt, where it has been baselessly accused several times of conspiring against the Land of the Nile. One common accusation against Israel in Egyptian public discourse is that Israel encouraged Ethiopia to harm Egyptian national water interests. On the other hand, there are also more sober voices in Egypt that recognize the nature of relations with Israel and reject the conspiratorial discourse. Such accusations against Israel have been pushed aside of the center of public discourse in Egypt lately, and Israel would therefore be wise to maintain a safe distance from the dam crisis and not furnish any pretext to revive them.

Although Israel is not and should not be a part of the water conflict between Egypt and Ethiopia, it certainly can participate in regional initiatives after the dam becomes a fait accompli. At the same time, because this is an existential issue at the heart of the national security of all parties involved, Israel must continue to conduct itself with the requisite sensitivity.

On the other hand, if and when Egypt and Ethiopia ultimately reach a compromise, Israel will be able to consider positively participation in the regional cooperation that Egypt seeks in the Nile Basin. Israel has advanced knowledge and technological tools in water and agriculture, and could positively contribute to the development of countries in the region, should they be interested in its assistance. Israel's strategic ties with Egypt in the energy field as part of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) could serve as a platform for promoting additional collaboration in this field. Sudan's increased openness toward Israel, as expressed in the February 2020 Netanyahu-Burhan meeting, emphasizes Israel's ability to maintain open ties with the third party in the equation. In the optimistic scenario, the dam will provide both Ethiopia and Sudan with tremendous opportunities to develop agriculture within their territories an additional field in which Israel can contribute and thus gradually expand its relations with Sudan.

Thus, although Israel is not and should not be a part of the water conflict between Egypt and Ethiopia, it certainly can participate in regional initiatives after the dam becomes a fait accompli. At the same time, because this is an existential issue at the heart of the national security of all parties involved, Israel must continue to conduct itself with the requisite sensitivity.