Publications

INSS Insight No. 1596, May 22, 2022

The terrorist attacks in Bnei Brak, Tel Aviv, and Elad by undocumented workers brought to the fore the phenomenon of workers’ easy entry into Israel through the barrier between Israel and the West Bank and their stay in Israel without permits. In fact, the number of undocumented workers in Israel has increased from about 20,000 on the eve of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic to about 40,000 in most of 2021, mainly due to workers switching from documented employment to undocumented employment. It is likely that Israeli policy during the pandemic, such as the requirement for employers to prolong workers’ stay in Israel, the associated costs of work permits, as well as the diversion of enforcement agents to COVID-19 regulations enforcement, contributed to the increase. On the other hand, the closure of the barrier following the terrorist attacks reduces the employment of undocumented workers in Israel, almost half of whom are unmarried and younger than those legally employed.

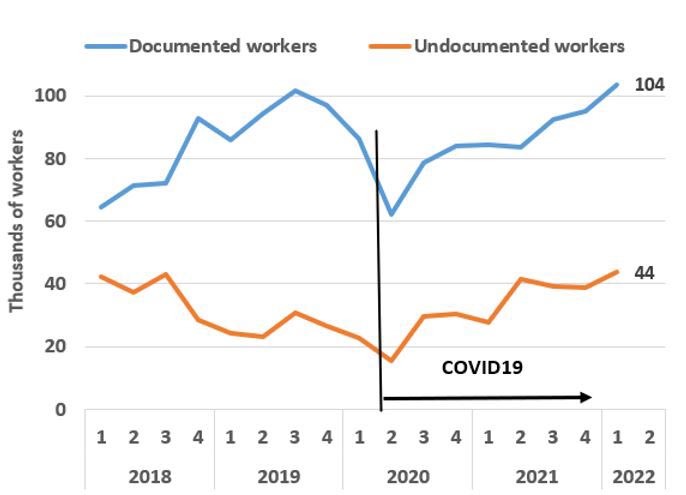

This article uses Palestinian surveys to examine the increase in the number of documented and undocumented Palestinian workers from the West Bank working in the Israeli economy (sovereign Israel and the settlements), after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 Q2-2021). At the beginning of the crisis, the number of undocumented workers (orange line in Figure 1) decreased from about 23,000 workers in the first quarter of 2020 to about 15,000 workers in the second quarter, the time of the first lockdown. However, subsequently, the number of undocumented workers in Israel increased and reached about 40,000 workers, starting in the second quarter of 2021. The increase in undocumented employment in Israel during the pandemic stands in contrast to the decline in informal employment during the crisis in many economies, including the Middle East.

At the same time, the number of documented workers in the Israeli economy (blue line in Figure 1), which stood at about 100,000 workers on the eve of the pandemic, dropped to about 62,000 in the second quarter (the first lockdown). Their number rose gradually in the second half of 2020 and during 2021. However, even in late 2021 the number of documented workers has not yet returned to the level on the eve of the outbreak.

Figure 1. Documented and undocumented Palestinian Workers in Israel and in the Settlements, 2018-2021, in thousands of workers

Source: Labor Force Surveys, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

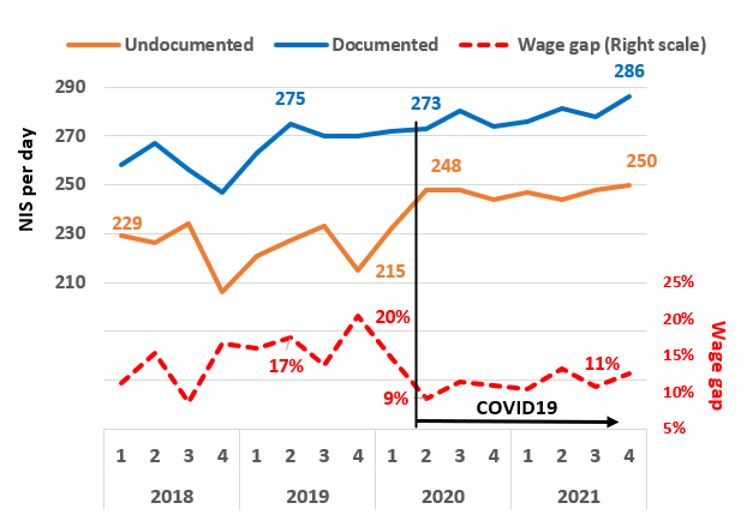

The pandemic was also accompanied by a reduction in the wage gap between documented and undocumented workers (red line in Figure 2): daily wages of undocumented workers (orange line) jumped with the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020 Q2 by about 11%, but the wages of documented workers (blue line) rose moderately. The rapid increase in the number of undocumented workers in parallel with the slow recovery in the number of documented workers, as well as the increase in wages of undocumented workers relative to wages of documented workers, suggests that during the pandemic the demand in Israel for undocumented workers increased.

Figure 2. Daily Wages of documented and undocumented Palestinian Workers in Israel and the Wage Gap, 2018-2021, in shekels per day and percentages

Source: INSS analysis of Labor Force Surveys, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

The Database

This study analyzes the microdata data of the Palestinian Labor Force Surveys (LFS) in 2018-2021. The LFS are household surveys conducted on a regular basis by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Every quarter, about 6,000 households in the West Bank are surveyed, including about 14,000 individuals aged 10 and over, some of whom work in Israel. Household representatives are asked about the nature of the work of household members, including documented and undocumented employment in Israel. Since the survey was conducted by the Palestinian CBS, there is no danger of participants avoiding reporting employment in Israel without an Israeli permit.

As a rule, the Palestinian CBS surveys the same household four times: in two consecutive quarters in a given year and in the following year (for example, first and second quarters in 2018 and 2019). This allows following the respondents’ changes of place and employment situation over time. However, the pattern sampling of households was disrupted during the pandemic. Therefore, we estimate the changes between employment statuses in a given quarter and the last time an individual was surveyed in the year or two prior to the interview.

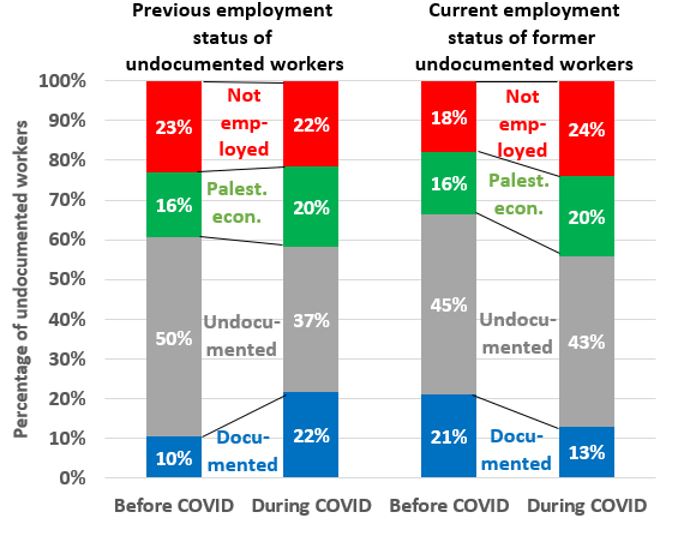

Change between Employment Status before and during the Pandemic

Figure 3 summarizes the transitions from one employment status to another for Palestinian cross-border commuters. Overall, it is clear that there is a decrease in the attractiveness of documented employment with a permit relative to undocumented employment during the pandemic. The percentage of undocumented workers who had previously been documented workers doubled from 10% before the COVID-19 outbreak to 22% after the outbreak, whereas the percentage of undocumented workers who switched to documented employment dropped from about 21% before the pandemic to about 13% during the crisis (blue markings in Figure 3). At the same time, the percentage of documented workers who continued as documented workers decreased during the pandemic (from 74% to 68%), and some of them work in Israel as undocumented workers (not shown in the figure). The overall shift from documented to undocumented employment pushed undocumented workers to seek employment in the Palestinian economy at a relatively low wage, or out of employment (green and red markings on the right side of Figure 3).

Figure 3. Previous Employment Status (year +) of Workers in Israel without a Permit, before the Pandemic (2017 - 2020 Quarter 1) and during the Pandemic (2020 Quarter 2 - 2021)

Source: INSS analysis of Labor Force Surveys, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

Thus, the decrease in the appeal of documented employment in relation to undocumented employment is also reflected in the reduction of the daily wage disparities (Figure 2), in the transition of documented to undocumented employment or employment in the Palestinian economy, and in the push of undocumented workers toward employment in the Palestinian economy or exit from the labor market (Figure 3).

A number of explanations can be offered for the decline in the appeal of documented employment during the pandemic in relation to undocumented employment. Initially, the entry of documented workers was restricted during the pandemic lockdowns, and workers could not legally enter through the workers' official entry-gates. Instead, many entered through breaches in the barrier. After that, employment was regulated by work permits that allowed workers to stay in Israel for several weeks, with part of the cost of accommodation and health insurance imposed on Israeli employers. In addition, employees of enforcement agencies, which were responsible for reducing the employment of undocumented workers, were reassigned tasks related to the enforcement of COVID-19 regulations. Thus, Israel's policy of reducing contagion through restrictions on Palestinian documented workers encouraged the entry of undocumented workers without supervision, which could have accelerated the spread of the virus. The increase in the number of undocumented workers was also made possible due to security forces turning a blind eye to the entry of undocumented workers into Israel.

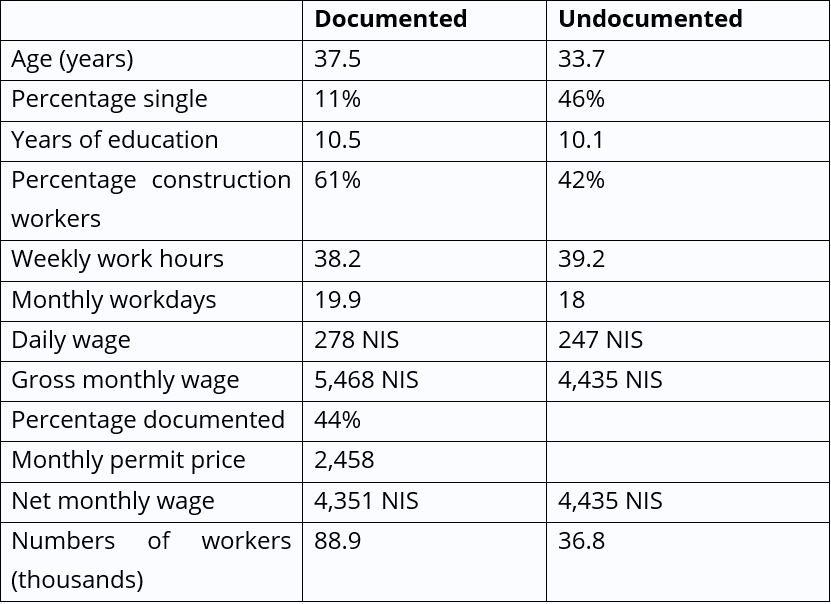

Reducing Undocumented Employment Harms the Youth and Unmarried

Closing the breaches in the fence following the recent attacks in Tel Aviv and Bnei Brak is expected to reduce employment of undocumented workers, who are on average about 4 years younger than the documented workers. In addition, about half of the undocumented workers are single, compared with about a tenth of the documented workers. These characteristics reflect the conditions for obtaining a work permit in Israel, which include “married status” and previously included conditions of age 25 and over. The daily wage of the permit holders is about 13% higher than the wage of the undocumented workers, and the gross monthly wage is about 23% higher due to the additional working days of documented workers. However, about half of the documented workers pay about NIS 2,450 a month for the work permit on the black market. Thus, the average monthly salary of the two types of workers in 2021 was about NIS 4,400 (Table 1).

Table 1. Documented Workers and Undocumented Workers, 2021

Source: INSS analysis of Labor Force Surveys, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

Summary and recommendations

Palestinian undocumented employment in Israel increased during the pandemic mainly as a result of documented workers switching to undocumented employment. This notable transition came about due to a combination of COVID-19 restrictions and policies that increased the cost of documented employment for both employers and workers, as well as diversion of forces to enforcing COVID-19 regulations. This transition in light of the pandemic, which due to the restrictions and increased cost of documented employment, emphasizes the need to balance the ease and cost convenience of documented employment employing documented workers. Therefore, future reforms regarding Palestinian employment arrangements in Israel should incentivize workers and employers to arrange Palestinian employment through official channels.

The increase in the number of undocumented workers was also made possible due to security forces turning a blind eye to entry into Israel of undocumented workers through known breaches in the barrier. According to media reports, security officials assess that undocumented employment in Israel helps maintain security stability and brings economic benefits to the Palestinian Authority and Israel. The recent terrorist attacks in Israel emphasize the security risks inherent in the ease of infiltration and stay in Israel. Israel also reaps economic benefits from the black market, which contradicts the government's policy of fighting the black market and reducing the use of cash. Moreover, undocumented employment is not limited to industries where permits are granted, and thus, if restricted may have negative spillover effects by harming the employment of unskilled Israeli workers in other industries.

Closing of the breaches in the barrier following the recent terrorist attacks and tightening Palestinian employment controls are expected to reduce the entry of undocumented workers into Israeli territory, and this reduction is expected to help Palestinian employers who have faced difficulty hiring workers in the past year due to competition with Israeli employers. At the same time, reducing the entry of undocumented workers will hurt mainly unmarried young people, who struggle to obtain a work permit. This situation will also increase the demand for the illegal purchase of work permits in Israel through the black market, emphasizing the need for strict enforcement of laws that prohibit this illicit trade. It is advised to examine whether “marriage status” as a condition for obtaining a work permit actually helps reduce the risk of terrorism.