Publications

Special Publication, Contemporary Antisemitism in the United States - collection of articles, October 13, 2021

Tom Eshed, a research assistant at the INSS project on “Contemporary Antisemitism in the United States,” examines how various government entities, law enforcement agencies, and civil society organizations collect and monitor data about antisemitism in the United States. He analyzes the advantages and shortcomings of each method and suggests how to responsibly use the various monitoring tools.

Introduction

A variety of government entities, law enforcement agencies, and civil society organizations—Jewish and non-Jewish—are engaged in tracking antisemitic incidents in the US. They maintain extensive databases, conduct opinion polls, and sometimes publish reports summarizing the state of antisemitism in the US and other parts of the world, including the number of incidents, their character, and trends in comparison to previous years. The databases presented in this research are currently the most basic tool for tracking antisemitic incidents and analyzing trends of antisemitism in the US. Monitoring the phenomenon is critical to measure and assess trends and changes, as well as to raise awareness of antisemitism among the general public, support processes of formulating strategy and decision making on the subject, and provide data that can be used in response in the context of enforcement, education, law, and maintaining the safety of Jewish communities and institutions.

This research discusses the two main methods currently used to assess antisemitism in the US—monitoring incidents and surveying public opinion—and presents the main organizations engaged in this activity. The methodologies used by the organizations to track incidents and conduct opinion polls are also examined, followed by a discussion of the challenges in measuring and assessing antisemitism, and finally recommendations for improving its measurement and assessment. Although this paper does not discuss these recommendations in depth, it suggests initial directions for thinking about the new and developing field of monitoring antisemitism in social media and about assessing the links between antisemitic perceptions, discourse, and actions.

Collecting and Monitoring Antisemitic Incidents

Databases, which publish daily reports of antisemitic incidents in the country, provide the most basic type of data collection on antisemitism in the US. Some databases collect relevant items from news websites and other sources of information, and others also receive independent reports.

The most prominent organization engaged in monitoring antisemitic incidents in the US is the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), an important American Jewish organization that focuses exclusively on the struggle against hatred and racism. Founded in 1913, the ADL has always engaged in the fight against hatred, racism, and antisemitism, and in promoting education against discrimination. It maintains a range of databases dealing with antisemitic incidents and the fight against antisemitism such as the Tracker of Antisemitic Incidents; most of the organizations concerned with monitoring antisemitism worldwide, and in the US in particular, rely on the ADL reports.

The ADL determines if a specific incident is an expression of antisemitism on the basis of the IHRA (International Holocaust Remembrance Association) definition. The ADL receives information about antisemitic incidents via reports from the public, the media, legal authorities, and experts in the organization. It examines each report and, when possible, cross-references with independent investigation.

Like other organizations, the ADL divides antisemitic incidents into three categories: harassment of Jews or Jewish institutions; vandalism of Jewish cemeteries or Jewish institution; and assault or the attempt to physically harm Jews due to antisemitic motives. The ADL does not monitor antisemitic incidents or statements in the private space (and therefore does not report them), such as at meetings of racist organizations. It also does not report about discrimination against Jews in general unless it is accompanied by verbal harassment of an antisemitic nature or antisemitic racist opinions.

As for expressing opinions against the State of Israel, the organization’s policy is to concern themselves only with incidents that employ obvious antisemitic stereotypes. Reports of antisemitic incidents on social media are included only if individuals or groups are harassed in places where they could reasonably expect not to experience such attacks. That means that the organization does not track the internet sites and forums of extremist groups, and these are not included in its reports (Anti-Defamation League, 2020).

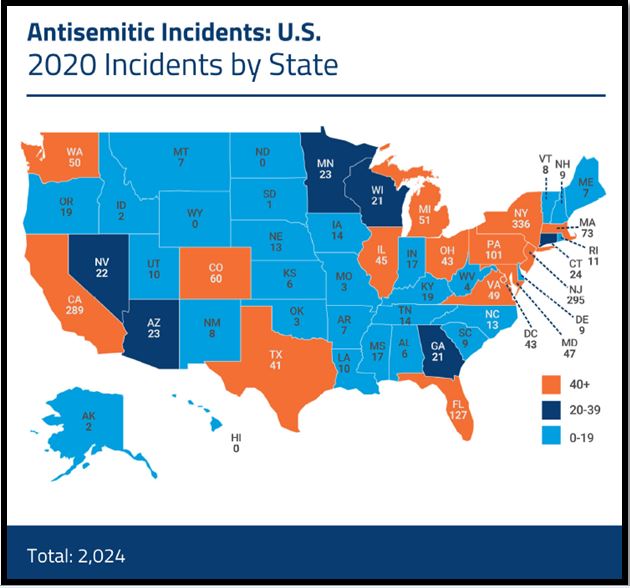

Figure 1. Antisemitic Incidents in the US in 2020 by State (Anti-Defamation League, 2020)

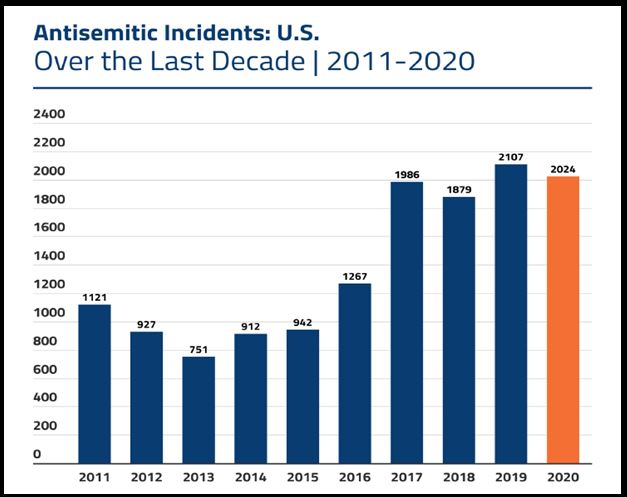

Figure 2. Antisemitic Incidents in the US Over the Past Decade (Anti-Defamation League, 2020)

The ADL website publishes daily compilations of antisemitic incidents and also a “HEAT map” (Hate, Extremism, Anti-Semitism, Terrorism) showing the locations of incidents linked to extreme ideologies—not necessarily antisemitic—in the US from 2002 to the present. The map specifies the type of ideology behind the antisemitic incidents: extreme left wing, Islamist, extreme right wing, and other. The incidents themselves are classified as anti-government actions, antisemitic incidents, extremist murder, terrorist plans, and attacks, extremists/police shootouts, white supremacist incidents, and white supremacist propaganda.

Since World War I, and particularly since the Human Rights Act was passed in 1964, the FBI has also tracked hate crimes in the US. A hate crime is defined as “an action of physical violence or vandalism whose motive is a prejudice against a specific group, including any crime against a person or property that is driven by prejudice based on race, religion, disability, sexual preference, ethnicity or gender identification.” (FBI, 2021). Violence against Jews comes under the category of prejudice based on religion.

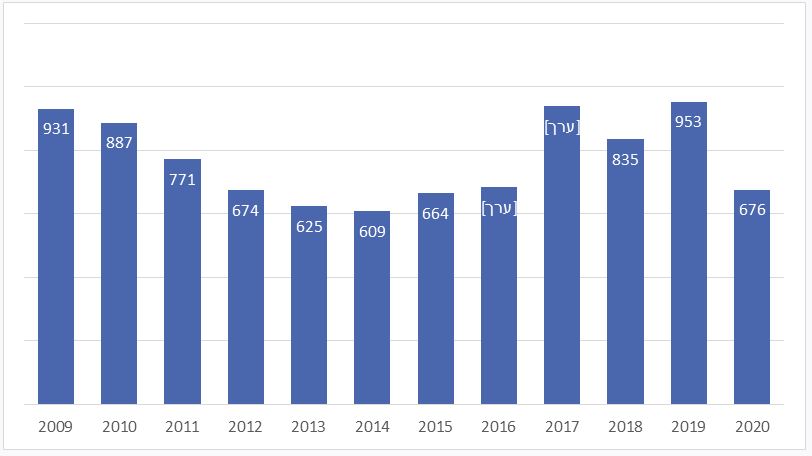

Once a year the FBI publishes data on hate crime in the US. In its latest report, the FBI reported a total of 7,759 hate crimes in 2020, 9% of which were directed against Jews, or 676 incidents. It is difficult to point to a specific trend from the FBI figures, since they show that in each year of the last decade, anti-Jewish incidents accounted for a similar proportion of all hate crimes reported by the organization. Most hate crimes in the US are racially motivated. Of the hate crimes reported in 2020, 36% or 2,755 incidents, were directed against African Americans (FBI Hate Crime Explorer, 2020). The chair of the ADL, Jonathan Greenblatt, was extremely critical of the latest report, noting that the antisemitic incidents reported by the FBI represents only a partial number of the hate crimes against Jews during 2020. According to Greenblatt, the fact that some local authorities reported zero hate crimes within their jurisdictions indicates that the figures are incomplete and do not reflect the true situation (Nakamura, 2021).

Figure 3. Antisemitic Incidents 2009–2020 Collected by FBI (FBI, 2020)

In Israel, the Kantor Center at Tel Aviv University publishes monthly reports of antisemitic incidents and an annual summary of antisemitism across the globe (Kantor Center, 2020). The Israeli government, and more specifically the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs, the Foreign Ministry, and until recently the Ministry of Strategic Affairs (which is no longer operates and its authority was transferred to the Foreign Ministry), also monitors antisemitic occurrences. The Ministry of Diaspora Affairs is the only one, however, that openly publishes summary reports of the information it collects. In addition, once a year it publishes its report on antisemitism, addressing the phenomenon throughout world and on social media during the previous year (Ministry of Diaspora Affairs, 2021).

It is also worth mentioning the database of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), an American civil rights group set up in the early 1960s, which has tracked hate groups associated with the extreme right wing since 2000. The organization, however, does not deal specifically with antisemitism, because it argues that all extreme right-wing groups are tainted to some degree or another with strong antisemitic views (SPLC, 2020).

The number of hate groups in the US declined from 2011 to 2014, but since 2017 this trend seems to be reversing. The proportion of neo-Nazi organizations among hate groups in the US dropped from about a third in the early 2000s to around a tenth in the years 2015–2016. Tom W. Smith, an expert on opinion polls, has pointed out that although neo-Nazi groups are the most antisemitic of all the organizations monitored by the SPLC, all other American hate groups promote prejudices and incitement against Jews to some degree. Although the increase in the number of hate groups could evince some rise in antisemitism in the US, it is impossible to draw conclusions about the prevalence or popularity of these views among the general public (Smith & Schapiro, 2019, pp. 120–122).

Other organizations monitor antisemitic incidents by tracking the activities of BDS groups and others who deny Israel’s right to exist. According to the organizations engaged in this type of monitoring, any activity linked to the delegitimization of the State of Israel is considered antisemitic. The AMCHA Initiative, for example, monitors antisemitic incidents on university campuses, including incidents targeting Jewish students and staff, antisemitic expressions, and BDS activity. Most Jewish organizations in the US do not agree that any effort to delegitimize Israel should be considered antisemitic. For example, according to the ADL, BDS or anti-Israel activity should only be deemed antisemitic if it uses clearly antisemitic stereotypes or expressions (ADL, 2018).

The Challenges and Difficulties of Monitoring Antisemitic Incidents

One problem of monitoring antisemitic incidents is that the reporting is incomplete, as no database contains all the relevant details. Since databases contain largely reports from the general public, any incident that is not reported does not enter the existing databases. This is a significant problem that concerns the experts and organizations who track hate crimes. While the FBI reports only a few thousand hate crimes in the US each year, experts estimate that more than 200,000 such crimes occur annually. Furthermore, only the FBI has a legal obligation to submit data on hate crimes, while other authorities do not have such an obligation. Consequently, some states and local authorities in the US annually report zero hate crimes (Joffre, 2019). The fact that US states and local authorities are not required by federal law to report hate crimes or antisemitic incidents means that the reports come only from states that have decided to collect such information (Morava & Hamedy, 2021).

At the same time, however, some incidents alleged to be antisemitic could, in fact, be not. Moreover, since the databases are based on reports, any increase or decrease in the annual number of reported events could be linked to the degree of awareness within the Jewish public of the reporting mechanisms and the extent of their concerns about antisemitism (Cohen, 2010, p. 93).

Duplicate reports is another problem. One incident may be recorded as dozens of different ones if many people report it. For example, in 2018 the ADL counted 1,879 antisemitic incidents, but it then emerged that 80 of them were in fact duplicate reports of one event—a recorded telephone message from a Republican candidate in California in support of white supremacy—that reached many telephones in Jewish homes and institutions (ADL, 2018).

Collection bias is an additional problem. In 2017, the ADL reported a sharp rise in the number of antisemitic incidents, but it then became apparent that at least 163 of the 1,986 incidents recorded that year were telephone or email threats originating from a young Israeli American Jew. His actions were not due to hatred of Jews, and thus these threats were not considered antisemitic incidents, although his messages included clear antisemitic indicators. This does not lessen the seriousness of the incidents but shows that counting antisemitic incidents is not an exact science.

We perhaps can obtain a better picture of the trends by focusing more on violent antisemitic incidents. For example, the ADL documented 19 violent attacks against Jews in 2017; 39 such attacks in 2018, and 61 attacks against Jews in 2019 (ADL, 2019a). This rise in violent attacks is a worrisome trend, which is easier to discern than a rise in the number of non-violent incidents, where awareness of their existence depends to a large extent on the public’s willingness to report them. Of course, the magnitude of the events is also important. The most serious attack on the American Jewish community was the shooting at a Pittsburgh synagogue in October 2018, in which 11 people were murdered in a single violent incident.

As already indicated, one of the main dilemmas in monitoring methods is how to relate to issues connected to Israel. While organizations such as the ADL do not deem criticism of Israel—such as that expressed by BDS organizations—as antisemitic in nature unless it includes clear antisemitic stereotypes, other organizations do consider any activity against Israel—and particularly any boycott of Israel—as antisemitic. This inconsistency over what constitutes an antisemitic incident creates certain differences in monitoring methods. The IHRA definition was supposed to assist in the creation of uniform criteria, but several organizations and groups that disagree with the IHRA definition have proposed other definitions (Bartov, 2021). The main monitoring organizations, however, have so far remained faithful to the IHRA definition, and there are no signs that they intend to change this.

This issue was subject to disagreement following the issuing of ADL reports on antisemitic incidents during the Israeli military operation Guardian of the Walls in May 2021. According to the ADL reports, 131 incidents were reported in the week prior to the military operation, while during the actual operation, they received reports of 193 incidents, of which 11 included violent attacks against Jews (ADL, 2021). According to Mari Cohen, a journalist for the progressive Jewish magazine Jewish Currents, the way that the ADL reported the increase in antisemitism created problematic bias. For example, at least 14 of the reports referred to statements and signs at pro-Palestinian demonstrations, which could be seen as expressing strong criticism of the State of Israel and its policies toward the Palestinians but not antisemitism (Cohen, 2021).

The political discussions around the definition of antisemitism and the question of when anti-Zionism becomes antisemitism (Stern, 2021) therefore affect the nature of monitoring antisemitic incidents, and they will probably continue to be points of controversy. It appears now that the main organizations engaged in monitoring antisemitism will continue to use the IHRA definition, in which some clauses and examples relate to the State of Israel. Presently, there is a relatively broad consensus over the IHRA definition, especially in the US and in the international arena in general. A growing number of governments and organizations have adopted this definition, but at the same time criticisms of the definition have increased. In 2021 a group of over 200 scholars and academics from a range of disciplines, such as Antisemitism Studies, Jewish Studies, Holocaust Studies, Israeli Studies, and Middle Eastern Studies, published the Jerusalem Declaration which contains a definition that diverges from that of the IHRA and includes different criteria for distinguishing between antisemitism and anti-Zionism.

Overall, the large number of entities engaged in monitoring and the number of standards, criteria, and parameters examined create a range of tools and outcomes. In addition, obtaining the most up-to-date picture of antisemitism requires consulting several databases, as each gives a partial picture based on different data. It is therefore difficult to obtain a complete and agreed upon understanding of the extent of antisemitism from all the organizations involved, although it is certainly possible to use the data to understand the trends and changes. For creating a comprehensive understanding of antisemitism, we need to refer to databases and monitoring services that have been operating continuously for long periods of time using the same standards and the same methods for tracking antisemitism, such as the ADL.

The significant methodological difficulties in achieving scientific, precise monitoring of antisemitic incidents notwithstanding, the purpose of the monitoring is not necessarily to track every single incident, even though law enforcement agencies have a clear interest in cataloging every hate crime that occurs in the US. One important role of monitoring of antisemitism is to raise awareness of the problem among the general public as well as among professionals and decision makers by means of regularly publishing information.

Public Opinion Polls

Opinion polls dealing with antisemitism address three metrics: the attitudes of the general population to the Jewish minority, the existence of antisemitic views and stereotypes in the general population, and how Jews themselves perceive antisemitism. A combination of these three metrices helps to provide an understanding of the general picture at any given time.

An accepted method of understanding how the general public in the US regards Jews is by measuring the percentage of people who are willing to vote for a Jewish candidate as US president. In 1937 only 46% of the American public expressed willingness to vote for a Jewish presidential candidate. Over the years this percentage has increased, until it reached 92% around 1999. Since then, the figure has remained stable.

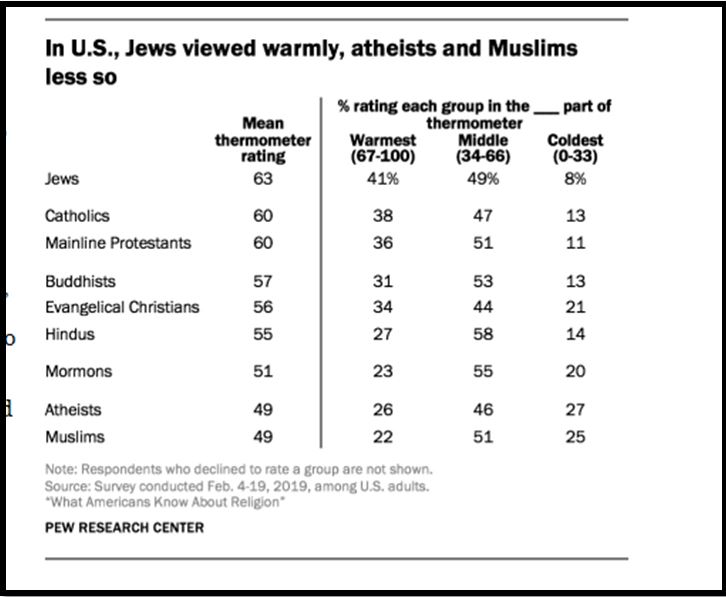

The rise in the proportion of the American public that accepts and likes the Jewish minority is expressed by other measures, for example by the affinity that the general public feels toward Jews (57.3% in 1976 vs. 70.6% in 2016) (Smith & Schapiro, 2019). In recent decades, the general public has given Jews a much warmer reception than any other religious group in the US, including Catholics, Mormons, Evangelicals, and Muslims. Philo-semitism—affinity toward Jews and belief in their contribution to global culture and society—may be no less significant than antisemitism in the US (Kampeas, 2019).

Figure 4. American Attitudes to Various Religious Groups (Pew, 2019)

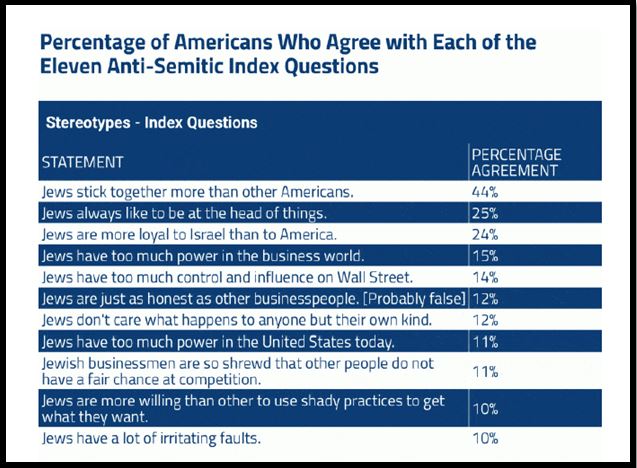

Since 1964, the ADL has conducted an annual survey including 11 statements that express classical stereotypes relating to Jews, for measuring the prevalence of anti-Jewish attitudes in American society as a whole. According to the ADL, a person is defined as antisemitic if they agree with at least 6 of the statements. In this survey, the ADL also asks about attitudes towards classical antisemitic stereotypes, for example, Jewish responsibility for the crucifixion of Jesus. In the ADL’s first survey of antisemitic attitudes in 1964, it found that about 29% of the American public agreed with six or more of the antisemitic attitudes. In the last survey in 2019, this figure had declined to 11% (ADL, 2019a).

Figure 5. Results of the ADL Opinion Poll of Classical Antisemitic Stereotypes (ADL, 2019b)

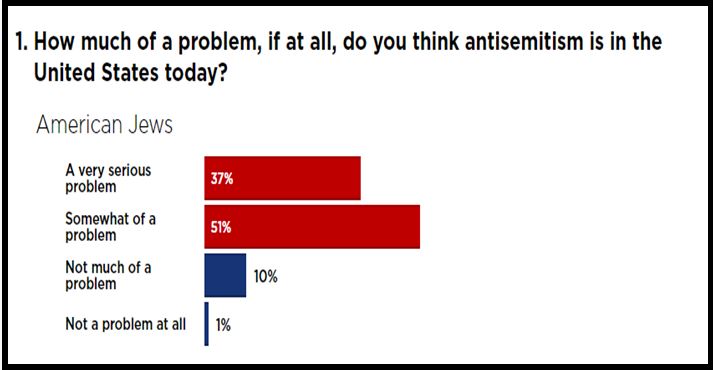

In recent years, the American Jewish Committee (AJC) has conducted an annual survey of how American Jews perceive the rate of antisemitism in their country. Participants are asked to what extent they think that antisemitism is a problem in the US today, whether they think that the problem has increased or decreased in the last five years, whether their security as American Jews has increased or decreased over the past year, whether they themselves have been victims of an antisemitic attack (physical, verbal or online) in the last five years, whether they are afraid to display Jewish signs in public, and what do they think the main source of antisemitism in the US is today (the extreme right, the extreme left, or extreme Islam) (AJC, 2020a).

In the 2020 survey, 88% of the Jewish-American respondents stated that antisemitism is currently a problem in the US, with 82% claiming that it had increased in the last five years (AJC, 2020a). This perception is not limited to a specific age group, political allegiance, or degree of religious observance. For example, in 2019, 93% of those surveyed who identified as Democrats, 75% who identified as Republicans, and 87% who identified with no party agreed that antisemitism was a problem in the US (AJC, 2019).

Figure 6. Results of a 2020 Opinion Poll by the AJC Showing Concern About Antisemitism Among Jews in the US (AJC, 2020b)

Of those surveyed, 49% of American Jews agreed that the threat from the extreme right is “very serious,” compared to 27% who felt the same about extreme Islam, and 16% who similarly viewed the extreme left. When asked about antisemitism in American political parties, 69% of the respondents thought that the Republican party harbored some degree of antisemitism while 37% said the same about the Democratic party. Orthodox Jews perceived more antisemitism on the left than on the right, with about 66% of Orthodox respondents claiming antisemitism in the Democratic party compared to only 22% who perceived this in the Republican party (AJC, 2020a).

The Pew Research Center, an apolitical non-profit research institute, conducts another important survey every five years about how American Jews perceive the degree of antisemitism. Its latest survey, published in May 2021, examines inter alia what US Jews think about their safety given antisemitism, as well as their perceptions of the phenomenon. The survey also examines the link between Jewish perceptions of antisemitism and their political views. Thus, for example, a correlation was found between views on the antisemitism and identification with either the Democratic or the Republican party. of the Jews who identified as Democrats, 81% agreed that antisemitism had increased in the US in the past five years, while only 61% of Jews who identified as Republicans agreed. (Pew, 2020).

Challenges and Problems with Public Opinion Polls on Antisemitism

A classic problem with public opinion surveys is that the wording of the question influences the response (Winiweski & Bilewicz, 2013, pp. 85–87). Mikolaj Winiewski and Michal Bilewicz showed how different formulations of the same questions in surveys relating to antisemitism can affect the responses given and they advise not to assume that the replies provide an exact representation of the breakdown of views about antisemitism in the general population (p. 88).

Another issue raised by experts is that the very fact of asking a question about Jews or antisemitism might elicit a problematic response because if the question had not been asked, the respondent would not be defined as antisemitic. There is also the reverse possibility: Respondents sometimes wish to please the questioners and may hide their real opinions (p. 94). A study done in Poland showed that when the respondents knows that a Jewish organization is behind the questions being asked, they are less likely to reveal their real attitude toward Jews (p. 95).

In addition to these biases, which influence any survey on any subject, researchers have also identified a particular breakdown and bias in replies given by Jews to questions on their feelings about antisemitism according to a range of conditions, such as age, socioeconomic status, political allegiance, identification with Israel, or a general affinity to Judaism (Rebhun, 2014, pp. 44–60). Jeffrey Cohen (2010) showed that the stronger a respondent’s Jewish identity, the lower their income, and the older they are, the greater the probability that they will feel that antisemitism is a serious problem (p.85). Moreover, Cohen demonstrates that Jews become more sensitive to antisemitism when they distinguish prejudices, discrimination, and/or attacks on non-Jews (Cohen, 2018, p. 407). In many cases, the timing of the survey can also reflect temporary moods that are influenced by specific incidents.

Although public opinion polls of various kinds are used to examine antisemitism during a given period, they should be used with caution. It is advisable to employ surveys that cover a longer duration and to utilize surveys from different sources in order to obtain as full a picture as possible.

Conclusions

From a historical perspective, the current situation of Jews in the US is good. American Jews are among those who are most educated in the US, have the highest incomes, and hold public positions and positions of influence that far exceeds their population rate (Lederhandler, 2021). Surveys also repeatedly show the degree to which the non-Jewish public has greater affinity for the Jewish community than for many other minority groups.

This does not mean that the risks and threats that the Jewish community has faced in recent years should be belittled or ignored. The rising trend in the number of violent and fatal attacks on Jews and Jewish institutions is extremely worrisome. Moreover, opinion polls in recent years have repeatedly revealed that the American Jewish public is concerned about antisemitism in the US and feels that it is increasing. However, caution should be used when examining the data indicating a general rise in the number of antisemitic incidents, given that the data collection on this topic depends considerably on media coverage or reporting to the legal authorities or the ADL. That is, Jews’ awareness of monitoring organizations and a general atmosphere of concern affect the extent of reporting antisemitic incidents; therefore, our attention should first and foremost focus on trends and violent incidents.

In order to obtain most comprehensive picture of antisemitism at any given time, data from opinion polls—about the general public’s attitudes to Jews and on how Jews themselves perceive the situation—should be combined with data about the number of antisemitic incidents, such as in the combined index produced by the Jewish People Policy Institute (Jewish People Policy Institute, 2019). This is a very reliable index that uses regular and serious sources and gives greater weight to credible data that are measured over a long period of time.

The purpose of monitoring expressions of antisemitism in the US is not only to track the phenomenon but also to raise public and political awareness of the problem and changing trends in its severity and frequency. Monitoring antisemitism aims to prevent serious outbreaks of harassment and violence against the Jewish minority and to prepare for managing the phenomenon. As long as antisemitic organizations, as well as antisemitic views, expressions, and actions are considered taboo in American society, Jews will feel secure. Monitoring is an additional tool—together with legislation, education, and information—to ensure that antisemitism remains taboo and that it is effectively addressed.

Although this paper did not discuss monitoring antisemitism on social networks, this issue should be considered elsewhere as social networks are fertile ground for the expression of antisemitic views, and since the middle of the last decade, an increasing number of organizations have been investing in resources to address the problem (see, for example, Oboler, 2016). In 2017, the ADL set up the Center for Technology and Society, which seeks to monitor harassment on social media and systematically investigate cases. In Israel, several entities, including the Ministry of the Diaspora and the non-profit organization “Fighting Online Antisemitism,” are active in this field by monitoring and reporting antisemitic content on social media. In contrast to the regular monitoring organizations surveyed here, which are largely civilian organizations that work with the legal authorities and seek to raise public awareness of the problem, in the case of social media, civil society organizations are doubly challenged as they monitor antisemitic activity on the internet, while also dealing with the companies that host social media platforms.

The large number of organizations now engaged in monitoring antisemitic incidents, which are constantly being joined by other entities and private individuals who also undertake initiatives on the subject, is evidence of interest and the sense of urgency for this activity. It also shows the scattered nature of the institutions of the American Jewish community and of the philanthropic institutions that allocate resources for this purpose. The traumatic events in recent years, such as the massacre at the Pittsburgh Synagogue in October 2018, also may have encouraged greater allocation of resources to the task of monitoring antisemitism.

In addition, an increasing number of websites of organizations that do not systematically monitor antisemitic incidents but collect reports from the media, invite site visitors to report to them any antisemitic incidents that they encounter. It is not always clear whether these organizations create databases of the information submitted to them, or if they forward it to the relevant authorities. While the numerous attempts to track antisemitism in recent years may be an indication of extensive interest by both Jewish and non-Jewish organizations, it also underlines their lack of cooperation with one another, perhaps due to mutual distrust or lack of will to cooperate. One of our recommendations is to invest further efforts into integrating all this activity.

Some of the organizations that monitor antisemitism in the US have been doing so in a professional manner for many years, but there are still many challenges to be addressed:

First, the inconsistency between the various monitoring entities regarding the definition of antisemitism, which could be a blessing but is also a curse.

Second, the absence of legislation at the federal level requiring the state law enforcement authorities to record and report antisemitic hate crimes.

Thirdly, the dispersal of the collected information among numerous organizations and databases presents only a partial picture.

To improve monitoring of antisemitism in the US, it is first necessary to address the huge gaps in reporting. These are apparently due to the lack of legislation requiring local authorities to report hate crimes in general and antisemitism in particular.

Secondly, to ensure that monitoring remains an effective and trusted tool, with positive media attention, it must be done cautiously, critically, and responsibly. The various indices must be prepared with full transparency regarding their basic assumptions and the definitions used. Although the public struggle against antisemitism can help Jews feel more secure, it is important not to exaggerate the phenomenon, since this could have the opposite effect.

Thirdly, it is worthwhile to examine the possibility of combining the various existing databases into a unified framework, giving both the public and researchers access to data from all the organizations engaged in the work for comparison purposes. Transparency of the raw data to the public will help to generate knowledge and insights that are not apparent.

Appendix: Main Organizations and Databases Monitoring Antisemitism

Click here to read the appendix.

References

American Jewish Committee. (2019). AJC Survey of American Jews on Anti-Semitism in America. https://www.ajc.org/AntisemitismSurvey2019

American Jewish Committee. (2020a). AJC 2020 Survey of American Jewish Opinion. https://www.ajc.org/news/survey2020

American Jewish Committee (2020b). The State of Antisemitism in America 2020: AJC’s Survey of American Jews. https://www.ajc.org/AntisemitismReport2020/Survey-of-American-Jews

Anti-Defamation League. (n.d). Tracker of Antisemitic Incidents. https://www.adl.org/education-and-resources/resource-knowledge-base/adl-tracker-of-antisemitic-incidents

Anti-Defamation League. (2018). Audit of Anti-Semitic Incidents: Year in Review 2018. https://www.adl.org/audit2018

Anti-Defamation League. (2019a). Audit of Anti-Semitic Incidents: Year in Review 2019. https://www.adl.org/audit2019

Anti-Defamation League. (2019b). Antisemitic Attitudes in the US: A Guide to ADL’s Latest Poll. https://www.adl.org/survey-of-american-attitudes-toward-jews

Anti-Defamation League. (2020). Audit of Anti-Semitic Incidents: Year in Review 2020. https://www.adl.org/audit2020

Anti-Defamation League. (2021, May 20). Dozens of anti-Israel protests; 17,000+ tweets of “Hitler was right” and increase in antisemitic incident reports [Press release]. https://www.adl.org/news/press-releases/preliminary-adl-data-reveals-uptick-in-antisemitic-incidents-linked-to-recent

Bartov, A. (March 8, 2021). Between anti-Semitism and legitimate criticism. Ha’aretz. https://www.haaretz.co.il/opinions/.premium-1.9655113

Cohen, M. (2021, May 27). A closer look at the ‘uptick’ in antisemitism. Jewish Currents. https://jewishcurrents.org/a-closer-look-at-the-uptick-in-antisemitism/

Cohen, J. E. (2010). Perceptions of anti-semitism among American Jews, 2000–05, A survey analysis. Political Psychology, 31(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00746.x

Cohen, J. E. (2018). Generalized discrimination perceptions and America Jewish perception of antisemitism. Contemporary Jewry 38, 405–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-018-9259-4

FBI. (2020). Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer. https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/hate-crime

FBI. (2021). What We Investigate. FBI. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/civil-rights/hate-crimes

Jewish People Policy Institute. (2019). Annual assessment of the situation and dynamics of the Jewish people. http://jppi.org.il/en/article/aa2019/

Joffre, T. (2019, April 15). Untold number of U.S. hate crimes go unreported by Feds. Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/international/untold-number-of-us-hate-crimes-go-unreported-by-feds-586783

Kampeas, R. (2019, May 4). An era of ‘philo-semitism’? The US will push countries to love their Jews more, anti-semitism monitor says. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. https://www.timesofisrael.com/us-will-push-countries-to-love-their-jews-more-anti-semitism-monitor-says/

Kantor Center. (2020). Antisemitism worldwide 2020. https://en-humanities.tau.ac.il/sites/humanities_en.tau.ac.il/files/media_server/Antisemitism%20Worldwide%202020.pdf

Lederhandler, E. (2021, August 1). Anti-Semitism in the United States in the historical and social context. Institute of National Security Studies. https://www.inss.org.il/he/publication/american-antisemitism-historical/

Ministry of the Diaspora. (2021, January 27). Anti-semitism in 2020: Picture of the situation, trends and incidents. https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/report_anti240121/he/anti-semitism_anti240121.pdf

Morava, M. and Hamedy, S. (2021, March 17). 49 states and territories have hate crime laws–but they vary. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2021/03/17/us/what-states-have-hate-crime-laws-2021-trnd/index.html

Nakamura, D. (2021, August 30). Hate crimes rise to highest level in 12 years amid increasing attacks on Black and Asian people, FBI says. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/hate-crimes-fbi-2020-asian-black/2021/08/30/28bede00-09a7-11ec-9781-07796ffb56fe_story.html

Oboler, A. (2016, January). Measuring the hate: The state of antisemitism in social media. Online Hate Prevention Institute. https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/ForeignPolicy/AntiSemitism/Documents/Measuring-the-Hate.pdf

Pew Research Center. (2019, July 23). What Americans know about religion. https://www.pewforum.org/2019/07/23/what-americans-know-about-religion/

Pew Research Center. (2021, May 11). Jewish Americans in 2020. https://www.pewforum.org/2021/05/11/jewish-americans-in-2020/

Rebhun, U. (2014). Correlates of experiences and perceptions of anti-semitism among Jews in the United States. Social Science Research, 47, 44–60. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.03.007

Smith, T. & Schapiro B. (2019). Antisemitism in contemporary America. In Dashefsky, A. & Sheskin, I. (Eds.). American Jewish Year Book (pp. 113–161). New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03907-3_3

Southern Poverty Law Center (2020). Frequently asked questions about hate groups. https://www.splcenter.org/20200318/frequently-asked-questions-about-hate-groups#antisemitism

Stern, K. S. (2021, June 14). Anti-Zionism, Antisemitism, and the fallacy of bright lines. Institute for National Security Studies. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/anti-zionism-antisemitism-and-the-fallacy-of-bright-lines/

Winiewski, M. & Bilewicz M. (2013). Are surveys and opinion polls always a valid tool to assess antisemitism? Methodological considerations. Jewish Studies at the Central European University, 7, 83–98. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311486718_Are_surveys_and_opinion_polls_always_a_valid_tool_to_assess_antisemitism_Methodological_considerations

_________

* Tom Eshed is a research assistant at INSS on its study of antisemitism in the US. He holds a BA in History and an MA in Jewish History, both from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He is currently a doctoral student at Hebrew University, focusing on the study of the commemoration the Holocaust in Israel’s cultural diplomacy.