Securing Israel’s Electricity System: Renewable Energy, Decentralization, and Climate Security

Editors: Galit Cohen, Nurit Gal, Gal Shani

Abstract

Over the past decade, the amount of natural gas in electricity generation in Israel increased significantly, while the use of coal and diesel declined. Alongside the economic and environmental advantages, the use of natural gas raises new issues of electricity security and systemic robustness, because it is supplied through only two pipelines from the offshore reservoirs to the coast, without any storage capacity within Israel. Moreover, gas-based production is concentrated at a small number of production sites, and the transmission of electricity to consumers depends on the reliability of the national transmission system. This dependence on a few sources and on a limited transmission route creates a growing risk to the reliability of supply, particularly in security or climate emergencies.

Beyond the energy dependence on gas, Israel faces a combination of intensifying climate threats and security threats. On the one hand, climate change causes prolonged cold and heat waves, exceptional electricity demands, and fires that threaten critical electricity infrastructures. Peak electricity demand is expected to rise by 30% to 40% by 2035 as a result of population growth, economic growth, the electrification of transportation and industry, and extreme weather events. On the other hand, Israel is an energy island, not connected to regional electricity grids, and therefore particularly susceptible to damage to its strategic infrastructures, both at sea and on land. Significant damage to a gas pipeline or a central transmission facility could lead to a widespread shutdown of electricity production and damage the functioning of the entire economy.

Renewable energy, in addition to its environmental advantages, is now an essential element for strengthening the system’s security, as it is based on local decentralized production that does not depend on a single gas pipeline or transmission line. Government Resolution 465, dated October 25, 2020, stipulated that by 2030, 30% of electricity will be produced from renewable energy. This goal is expected to be achieved mainly by relying on solar energy, but according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), success depends on substantial investments in grid infrastructure, an area in which Israel’s rate of progress is still less than required.

To meet the goal, Israel must build renewable energy facilities with a cumulative capacity of 17,000 megawatts, of which only 7,000 megawatts have been connected to the grid to date. Currently, the Minister of Energy is examining an additional goal for 2035 in the range between 35% and 45% of energy production in that year. Increasing the goal will require establishing additional solar generation capacity in an amount yet to be determined, as well as expanding smart transmission and distribution infrastructures.

The potential to increase the scope of renewable energy production is divided into two main types:

- Consumer-adjacent installations—including rooftop installations, covering open urban areas such as parking lots, cemeteries, and sports fields, and installations on building facades (Building-Integrated Photovoltaics, BIPV). These installations offer an optimal solution to the risk because they do not depend on the national transmission grid. However, the potential for deploying decentralized installations is limited and does not fully meet the demand.

- Installations remote from consumption areas—including ground-mounted installations, agrivoltaic installations in agricultural areas, installations on water reservoirs, and rooftop installations in peripheral areas. Although these installations are remote from consumers, they are essential for meeting the goal. Moreover, installations connected to the transmission grid are under the control of the system operator and make it possible to route the energy to consumption areas as needed; therefore, these installations have a unique and vital role in emergencies and crises, especially if storage is integrated into them. Integrating these installations requires development of the transmission grid in order to deliver the energy to the consumption areas in the center of the country.

This paper reviews the threat to the gas infrastructure and the possible solution of renewable energy for strengthening energy security:

- Part A reviews the threat to energy security arising from the climate crisis and from security threats.

- Part B reviews two types of solutions to strengthen Israel’s energy security, by integrating renewable energies and strengthening decentralization. Developing local grids and consumer-adjacent production will not be able to meet the entire demand for electricity, so remote production is also required; hence the immense importance of developing the transmission grid.

The work process included two meetings at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS). The first seminar was held on April 28, 2025, during which the barriers to developing the grid and possible solutions were examined. The second seminar was held on July 10, 2025 and focused on the feasibility of independent local grids and on recommendations for promoting these grids in Israel. The meetings were attended by government officials, representatives of private companies, representatives of the Israel Electric Corporation, and the system operator. Below is a breakdown of the main insights from the thought process.

The two courses of action are also consistent with the IEA’s recommendation from its 2025 report,[1] according to which a combination of developing a modern transmission grid and decentralizing the grid is key to energy resilience. Developing an extensive transmission grid allows for efficient management of remote generation, while microgrids ensure functional continuity even when disconnected from the national grid. Development and decentralization complement each other and are required to maintaining the security of Israel’s electricity system.

Developing the Transmission Grid to Connect Remote Renewable Energy Facilities

In 2023, the energy minister approved a plan to develop the delivery system totaling approximately 22 billion NIS,[2] of which approximately 12 billion were designated for connecting renewable energy facilities. However, an oversight report published by the Electricity Authority on January 8, 2025indicates that the plan to develop the transmission grid is delayed. [3]

The main recommendations for promoting the development of the transmission grid:

- Updating the grid development plan in two key aspects:

- Integrating potential areas for agrivoltaic production into the development plan—to enable future connection;

- Integrating high-demand facilities (such as Data Centers) in solar production areas to reduce the need for grid development.

- Formulating an acceleration plan for grid development via a dedicated subcommittee in the National Infrastructure Planning Committee (known by its Hebrew acronym, VATAL). The committee’s authorities will be defined in the Arrangements Law, and appropriate staffing to enable its operation will be allocated. The committee will advance plans via a regional perspective of several lines together and will also be authorized to grant building permits.

- Expanding the policy of undergrounding lines in the transmission grid that will address objections that currently delay the construction of grid lines.

- Formulating a plan to increase the utilization of the existing grid:

- Implementing advanced technologies that will make it possible to increase and efficiently manage the load on the grid lines—advanced conductors, sensors, control and management systems.

- Updating the load criterion on the lines and implementing a dynamic load policy, so that the load is adjusted to the status of the lines in practice.

- Increasing grid flexibility—by integrating storage and advanced management tools, in accordance with the IEA’s recommendation.

- Increasing information transparency—publishing updated information for the public and publishing the grid connection queue.

- Integrating the private sector in planning and building grid components—This will be subject to criteria set by Noga (Israel Independent System Operator Ltd.) in coordination with the Israel Electric Corporation (IEC).

- Reestablishing the barrier removal committee and publication of the committee’s deliverables to the public, in order to address the difficulties emerging in the planning process.

Establishing Local Grids that Can Operate Independently in Emergencies

A microgrid is a group of consumers and decentralized production assets connected to each other within a defined electrical grid, which operates as a single, controllable entity in relation to the electrical grid. A microgrid can connect and disconnect from the grid, so it can operate in both grid-connected mode and in islanded mode (DOE).[4]

In recent years, electricity systems in Israel and worldwide have increasingly focused on the option of establishing microgrids, subsequent to four revolutions occurring in the electricity sector: a shift to clean generation with renewable energy (decarbonization); decentralized consumer-adjacent generation (decentralization); smart management and control systems (digitization); and more recently the storage revolution (storage).

These revolutions, as well as the security threat to the electrical grid and the risk of extreme climate events disrupting the electricity supply, encourage the establishment of microgrids that will enable the smart management of demand, generation, and storage, and, in extreme scenarios, will also be able to operate if disconnected from the national grid. Electricity security in the 21st century is measured not only by the size of the national system but also by its ability to function in a decentralized manner, adapt to extreme situations, and rapidly recover from them.

Worldwide, microgrids can be found on technology campuses such as the Siemens campus in Vienna and universities, on remote islands, and in other isolated systems such as mines, ships, and rigs. According to IEA data, the number of microgrids in the world is expected to nearly double by 2035, mainly around essential industrial facilities, civilian campuses, and hospitals—as preparation for extreme climate events.

In Israel, initial steps are being taken to establish microgrids in several kibbutzim, because the grid in these communities is owned by a local distribution company (“historic distributors”), a significant portion of consumption is already generated today on the kibbutz, and many kibbutzim are in the process of integrating storage into the local grid. In communities where the grid is owned by the Israel Electric Corporation, such as cities, moshavim, and villages, local grid management can be implemented, but regulation is required to enable this. In light of this, independent management capability is being promoted in individual buildings in these communities (e.g., in resilience centers) and not in the public grid.

Independent operation of a local grid poses a technological challenge, because it is necessary to manage the transition from grid-connected mode to islanded mode without disruption to consumers and while stabilizing and managing the load, voltage, and frequency using local assets, effectively handling short-circuit currents, and implementing protection and safety measures. All of this applies in islanded mode as well, where it is not possible to rely on the national grid.

Added to the technological difficulty is also an economic challenge: For production and storage systems, there is existing regulation that creates economic viability for the investment.[5] However, there is currently no economic incentive to built and operate smart systems to manage a local grid.

The development of microgrids could have various advantages at the national economic level, specifically savings in developing the transmission grid and production capacity through better utilization of local production, a solution for isolated and remote consumers whose connection to the national grid is expensive and lengthy, expediting the construction of renewable energy facilities, lowering the cost of supply to consumers, and minimizing non-supply minutes. However, encouraging the establishment of microgrids requires investing resources in funding all the consumers in the sector, and therefore the economic benefits must be quantified before establishing incentives and regulation for microgrids.

Recommendations for Promoting Local Grids in Israel:

- Technological development of systems for autonomous management of the grid;

- Subsidizing grid management systems in remote and threatened locations;

- Developing national pilot programs for smart grids and microgrids in collaboration with the system operator;

- Encouraging the use of independent inverters that enable operation when disconnected from the grid;

- Regulation of standards for disconnecting microgrids and for interfacing between an independent grid and the IEC’s grid.

Part A

Chapter 1: The Climate Crisis as a Challenge to National Security and to the Electricity System in Israel | Galit Cohen and Gal Shani

For years, the climate crisis was discussed primarily in the environmental context, as a challenge that jeopardizes ecological systems, biodiversity, and natural resources. However, it is now increasingly clear that this is a broad, nationwide, multi-system challenge, which threatens not only the environment but also the State of Israel’s security, economy, and resilience. Climate change is increasingly affecting every area of life—from water and agriculture systems to transportation, health, and energy infrastructures, which enable all the rest to function.

Meanwhile, the electricity sector, which in effect serves as the backbone of all systems in the economy and society, has been under mounting pressure in recent years. In Israel—a small state fraught with risks and isolated from its regional surroundings from an energy aspect—the implications of climate change could be especially severe. This past summer, characterized by prolonged heat waves, record high temperatures, and unprecedented electricity loads, sharply illustrated the fragility of the existing system and its limitations in dealing with extreme scenarios. Added to this was the Swords of Iron War, which further underscored how a disruption to the electricity supply, whether as a result of a cyberattack, damage to physical infrastructure, or a production shortfall, could inflict severe damage to the economy, consumers, and the functioning of the state as a whole.

According to the International Energy Agency, the concept of electricity system security in the 21st century is changing fundamentally. Electricity security is no longer measured solely by the ability to generate electricity but also by the ability to respond, adapt, and recover from extreme climate, security, and technology events. The security of the system currently rests on three key components: Diversification of production assets, operational flexibility, and physical and digital resilience of the transmission and distribution grid.

Climate trends in Israel add another layer of complexity to this challenge. According to the Israel Meteorological Service, 2024 was the second warmest year recorded in Israel since 1950, with a particularly hot summer that set new temperature records for the country. The average temperatures during the hot months were higher by about two degrees Celsius than the historical average, and surpassed the previous records measured in 2012 and 2023 by more than half a degree Celsius. Furthermore, during the winter of 2024, the amount of precipitation was exceptional, with heavy rains and destructive hailstorms in certain areas, while desert areas experienced one of the driest years on record.

According to the IEA 2025 report,[6] in 85% of power outage cases worldwide in recent years, the cause was extreme climate events—including storms, floods, fires, or heat waves—which mainly damaged transmission lines and substations. Exceptional climatic fluctuations, prolonged heat waves, extreme precipitation, floods, and fires could have direct and substantial consequences on Israel’s electricity system. They could reduce the efficiency of power plants, damage transmission infrastructures, and increase the demand for energy, driven by cooling needs in the summer and heating in the winter.

These phenomena add to the Israeli economy’s growing dependence on a stable and continuous electricity supply, stemming from ongoing trends of electrification of transportation systems, building energy-intensive desalination facilities, the expansion of data centers, and the steady growth in communication and digitization services. The IEA estimates that by 2035 there will be an increase of about 40% in peak electricity demand worldwide, mainly due to the electrification of transportation and industry, a trend evident in Israel as well, where demographic growth and a growing economy further accelerate the rate of increase.

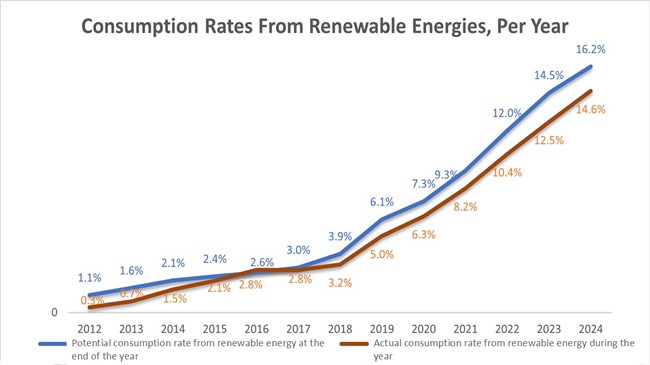

All these pose a real challenge to the existing electricity infrastructures and put the system’s ability to meet the growing demand to the test (see Figure 1). Concurrently, the global energy system is in the midst of a deep structural and economic shift stemming from the global transition to renewable energy sources—a process also occurring in Israel, leading to a significant increase in the integration of solar installations and energy storage projects, which require development of the transmission and distribution grid.

Figure 1. Consumption Rates From Renewable Energies, Per Year

Note. Taken from the Electricity Authority, Report on the State of the Electricity Sector (September 2025).

Climate change increases the pressure on the electricity sector. Prolonged heat waves increase electricity demand, while the efficiency of power plants and the grid declines at high temperatures, thereby creating higher susceptibility to failures and shortages. The economy, which already depends on an almost uninterrupted supply of electricity for all facets of life, is becoming vulnerable to extreme weather events as well. The IEA notes that a one-degree Celsius increase in the average summer temperature could reduce production efficiency at conventional power plants by about 3%, and cause an increase of tens of percent in peak loads.

For example, in August 2025 the newspaper Israel Hayom reported that at the Givati Brigade’s Sayarim Base in the south, it was decided to send hundreds of soldiers home after an extreme heatwave caused the collapse of the electricity and air conditioning systems, and the temperature inside the buildings reached about 60 degrees Celsius.[7] That same week, additional power outages were recorded in the south due to unusual heat loads that caused malfunctions in the local grid, and concurrently, a national record for electricity consumption was measured—15,806 megawatts.[8] Furthermore, the heatwave in May 2025 caused huge fires in the Galilee and the Beit Shemesh area, which tripped high-voltage lines and disrupted electricity supply to thousands of residents.[9]

In addition, Israel faces a direct security threat to its principal energy assets. The gas fields, rigs, and subsea pipelines are concentrated, high-visibility strategic infrastructures, and therefore constitute a target for attack during conflict. The Swords of Iron War demonstrated the degree to which energy infrastructures, at sea and on land, are exposed to direct threats, including missiles, drones, and cyberattacks. This vulnerability is amplified by the energy sector’s centralization and its reliance on a limited number of natural gas facilities, which supply about 72% of electricity production. This dependence increases the risk of widespread disruptions in energy supply during emergencies and combat.

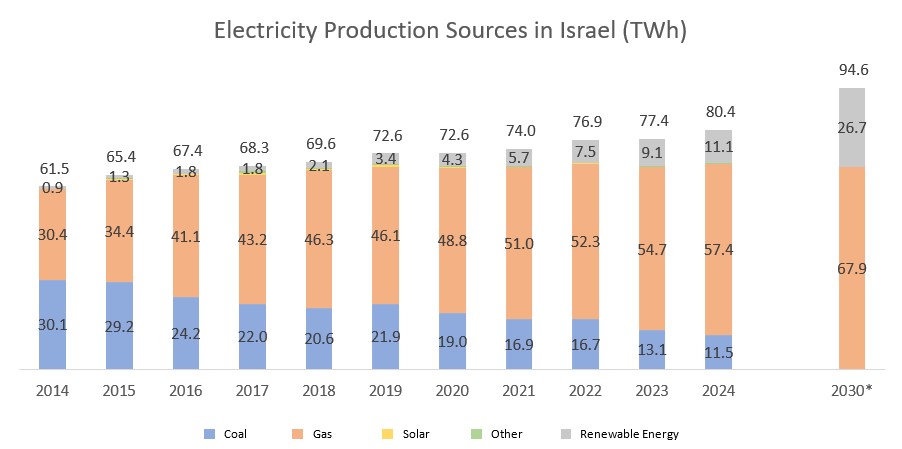

Figure 2. Electricity Production Sources in Israel

Note: Taken From the Electricity Authority, Report on the State of the Electricity Sector (September 2025).

In this context, the IEA emphasizes that countries with a high dependency on centralized production facilities are required to develop decentralized backup networks—local and regional production systems that will ensure supply continuity even if a central facility is damaged.

Due to the various climate, technology, and security challenges Israel faces (which will be detailed in the next chapter), the question of the electricity system’s resilience is gaining significance. Its centralization creates a dependency on a small number of power stations and distribution and transmission infrastructures, making the system particularly vulnerable to unexpected events, both natural and man-made. The centralization of Israel’s electricity system stems from several historical and structural factors, chief among them considerations of security and supply reliability, which for decades led the state to prefer a centralized system that is uniformly controlled and managed, based on the perception that centralized control would enable a rapid and effective response during emergencies. Israel’s energy isolation, since it is not connected to a regional or international electricity grid, has reinforced this trend, as it requires tight management and full coordination among all components of the system to maintain its stability and prevent a collapse. Even today, despite the entry of private producers and power stations based on gas and solar energy, the sector’s structure remains centralized by nature, as transmission and distribution remain in the hands of a single entity and are not open to competition.

The concentration of production and control in a limited number of facilities and infrastructures increases the risk that technical failures, cyberattacks, or physical damage to a central facility will affect the entire sector. A centralized system also tends to be less flexible and innovative, finding it difficult to integrate decentralized production from renewable sources and to respond to demand fluctuations in real time. Therefore, although centralization has provided advantages of control, coordination, and operational security over the years, in an era of climate change, growing security threats, and a transition to renewable energy, it may turn from a structural strength into a strategic weakness, one that requires rethinking the structure of Israel’s power grid.

In the face of this reality, there is a growing understanding that a conceptual shift is needed, as well as the development of a smarter, more decentralized electricity grid that can function during routine and emergencies. One of the main advantages of a decentralized grid based on local production facilities such as solar systems installed on rooftops combined with storage technologies, is that production, storage, and consumption occur in the same place, thereby reducing the dependence on large generation centers and the national transmission grid. However, underdevelopment of the transmission and distribution grids currently limits the ability to integrate decentralized production from renewable sources, especially in areas far from the country’s center where the solar potential is high. Added to this are regulatory, economic, and security barriers that delay the expansion of the grid and the integration of green electricity.

The 2025 IEA report defines the investment gap in electricity grids as “the central bottleneck of the global transition to clean energy” and emphasizes that investments in grids and storage need to double by the end of the decade to maintain the system’s reliability and resilience.

To ensure the survivability and resilience of the electricity sector in an era of growing uncertainty, Israel must expedite infrastructure development with an emphasis on promoting decentralized production facilities and large-scale energy storage. A combination of decentralized production facilities, storage systems, and real-time load management is a fundamental condition for Israel’s ability to cope with the challenges of the future—the climate crisis, population growth, security threats, and the transition to a green economy—and to build a robust, stable, and sustainable electricity sector that part of the national resilience.

Chapter 2: Threats to Israel’s Gas and Transmission Infrastructures in the Maritime Domain | Yuval Eylon

When discussing Israel’s energy sector, one must examine the security threats and risks to Israel’s strategic energy sites in the maritime domain—the Tamar, Leviathan, and Karish gas fields—and to the undersea gas transmission infrastructures.

In the past decade, natural gas has become an essential component of Israel’s energy and economic continuity—both for internal electricity supply and for regional export. Damage to a rig or to undersea transport infrastructures that move gas from the depths of the sea to the production rigs, and from the production rigs—a distance of many tens of kilometers—toward the onshore storage and transport infrastructures, could cause the shutdown of Israel’s electricity sector and have additional broader implications for the electricity sector, for export contracts, and for the energy balance in the entire Middle East, as it is not just the State of Israel that depends on the gas produced from the gas fields located in its economic waters.

In recent years, and even more so during the Swords of Iron War, gas production or transportation at these facilities was halted due to the need to protect these facilities against various forms of attack. The defense belts were designed and built in recent years primarily against aerial threats, such as unmanned aerial vehicles and a variety of missiles that can be launched from land to the sea, which challenged the entire energy sector and the strategic assets at sea. However, as we experienced once again in the last war, it is not possible to guarantee a hermetic defense that will thwart and intercept all threats with absolute 100% success. Therefore, several times during the last war, as well as in a number of past combat events, Israel’s gas production fields were shut down in order to prevent immense damage if they were to be hit.

The threats to the gas rigs and to the aforementioned transport infrastructure are diverse, and can be divided into surface and subsurface threats. The ability of militaries, terrorist armies, and terrorist organizations to employ a wide range of threats capable of harming an important strategic facility, which spans an area of several hundred square meters and stands in a fixed and known location, is constantly improving, coupled with, of course, the capabilities to contend with such threats.

Missiles launched from the shore or missiles launched from vessels, carrying tens of kilograms of explosives, pose a very serious threat to these facilities, alongside additional manned and unmanned aerial capabilities that have been developing rapidly in recent years. This is coupled with threats that can reach these facilities on the water’s surface in the form of manned or unmanned vessels, damage the gas rigs, and inflict significant damage upon them. The State of Israel has built extensive and effective defense belts against these threats, which proved themselves in the last war, demonstrating impressive operational cooperation between the intelligence capabilities and the combined interception and defense capabilities of the Air Force and the Navy. However, the activation of a wide range of capabilities of the type described, in large quantities simultaneously, may overwhelm the aforementioned defense capabilities, and place the State of Israel’s energy continuity at risk. A strike by this type of threat against an active rig can cause enormous damage that could disable the ability to produce or flow gas for prolonged periods of weeks and even months. Such a strike on a cooled rig would cause far less damage and could lead to a shutdown of days to weeks, depending on the type of strike and the extent of the damage.

Coupled with the surface threats, there are quite a few underwater threats that can critically harm the energy sector by striking underwater production facilities—not only the actual gas rigs but also the transport infrastructure that flows the gas from the drilling and production areas to the gas storage and transport infrastructures in Israel and in other countries that benefit from the gas produced in Israel’s economic waters.

These underwater threats are diverse and threaten the infrastructure laid on the seabed—threats from manned and unmanned submarines, and especially from unmanned underwater vehicles, which can now be operated remotely to cause heavy damage that is complex and very expensive to repair, and requires a very high degree of skill. During Operation Guardian of the Walls we experienced attempts by the terrorist organization Hamas to strike Israel’s energy infrastructure with an unmanned underwater vehicle carrying tens of kilograms of explosives targeting this infrastructure, and in the recent war, these attempts intensified and became more sophisticated.

Although the IDF managed to thwart and prevent this attack against energy infrastructures, we are seeing significant development in the underwater domain worldwide, manifesting in the development of capabilities to damage subsea transmission infrastructure—communications infrastructure or energy infrastructure. It can be seen that in our region, terrorist armies are investing numerous resources to improve their capabilities in this domain. A strike on underwater transport infrastructure could cause heavy damage and critically harm the gas supply. Needless to say, repairing such damage at a great depth of hundreds of meters below the sea is highly complex, lengthy, and expensive, and very few countries and commercial companies have the capability and know-how to provide such a solution. Such a strike could lead to a shutdown of several weeks, in a best-case scenario.

The State of Israel invests significant resources and efforts to protect its strategic assets at sea, affording it energy and functional continuity. However, it must be remembered that we will never succeed in achieving an absolute and hermetic response that will prevent any ability to harm or threaten these infrastructures, coupled with the constant need to examine the level of investment against the level of risk. In order to enable Israel’s energy continuity, it must be remembered that the solution lies not only in investing in defensive belts, in their improvement and refinement, but also in improving redundancy and the possibility of “placing the eggs in more than one basket.” Therefore, the State of Israel’s ability to currently produce gas from more than one field or production site, as well as the ability to create transport infrastructures that are not dependent on only one transport line, are essential and provide part of the solution. It is important to remember and continually examine additional alternatives to gas in Israel’s energy sector, which depends almost entirely on gas produced from the sea, even if only for short periods when this redundancy is required.

Part B

Chapter 3: Developing the Transmission Grid for Connecting Remote Renewable Energy Facilities to Israel’s Electrical Grid

The electrical grid is responsible for transporting energy from production facilities to consumers. The grid in Israel is a closed system that is not connected to neighboring countries (“electrical island”).

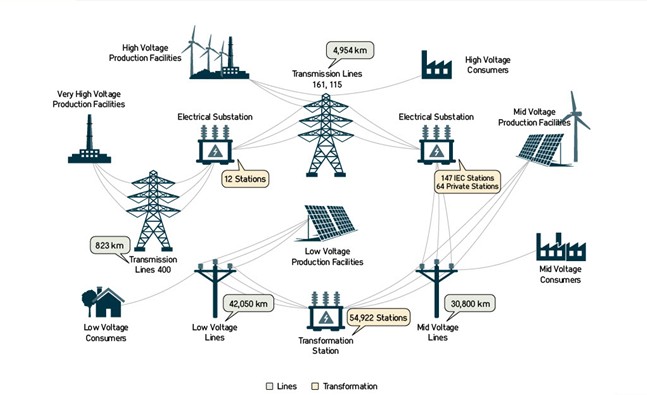

The grid operates at three main voltage levels (see Figure 3):

- Ultra-high voltage transmission grid and extra-high voltage transmission grid are used to connect power stations with a capacity of hundreds of megawatts. The ultra-high voltage grid is about 800 km long, and the extra-high voltage grid is about 5,000 km long.

- High voltage distribution grid is used to transfer energy from the extra-high voltage grid to consumption areas. The grid is about 31,000 km long.

- Low voltage distribution grid is used to transfer energy within distribution areas to consumers. The grid is about 42,000 km long.

Figure 3. Structure of the Electrical Grid in Israel, 2023

Note. Taken from Electricity Authority, Report on the State of the Electricity Sector (September 2024), 51.

Energy transfer between voltage levels occurs via transformation:

- Transformation from ultra-high voltage to extra-high voltage—via 12 switching stations.

- Transformation from extra-high voltage to high voltage—via 212 substations.

- Transformation from high voltage to low voltage—via 55,000 transformer stations.

Consumers are connected to the grid according to their peak demand:

- Energy consumers with a power capacity greater than 16 megawatts are connected to the extra-high voltage grid (such as the oil refineries, the Dead Sea Works).

- Energy consumers with a power capacity between 630 kilowatts and 16 megawatts are connected to the high voltage grid (such as shopping malls, industrial centers, and office towers).

- Energy consumers with a power capacity under 630 kilowatts are connected to the low voltage grid. This category primarily includes residential consumers, but also small consumption sites (such as schools, small public buildings).

In the past, all power was generated at power stations connected to the extra-high voltage grid, so to reach end consumers, the power flowed from the transmission grid to the high voltage grid, and from there to the low voltage grid. Since 2010, the volume of production at decentralized power plants has gradually increased, mainly at renewable energy and storage facilities. Some of these facilities are connected to the low voltage grid or to the high voltage grid near consumption areas, so the flow of energy to consumers from these facilities occurs through a shorter process. Surplus renewable energy production from facilities connected to the distribution grid is transferred to the transmission grid via substations, and from there to consumers in remote demand areas.

The flow of energy along the grid and through the transformer facilities involves a loss of about 6% of the energy produced. The transition to decentralized production has reduced the loss along the grid.

Grid Development Plan

In 2023–2024, plans were approved to develop the transmission grid and the distribution grid. The investments aimed to:

- connect additional consumers (households and new buildings);

- connect approximately 10 thousand megawatts of additional renewable energy facilities.

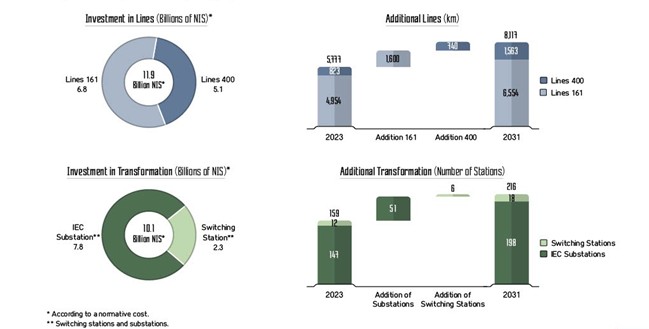

Figure 4 presents the development plan for the transmission network. The total cost of the program is around 22 billion NIS, of which about 12 billion are designated for connecting renewable energy facilities.

Figure 4. Transmission Grid Development Plan

Note. Taken from Electricity Authority, Report on the State of the Electricity Sector (September 2024), 52.

An oversight report published by the Electricity Authority in 2024 shows that only a third of the projects are expected to be completed on schedule.[10] The report found that the primary reasons for the delays pertain to a delay in the statutory approval process, due to opposition to the line or a demand for undergrounding. The report further indicates that the demand for undergrounding persists even after the plan to establish the line was approved.

Environmental Aspects of Grid Development

In general, the Ministry of Environmental Protection’s policy prioritizes establishing production facilities near consumption areas, in order to minimize the need to build grid lines. However, the Ministry allows the construction of grid lines as needed, while addressing environmental aspects.

Environmental considerations in grid development:

- Ecological impacts—minimizing the impact on ecological diversity resulting from the construction of access roads, clearing vegetation, and risk to birds;

- Radiation—public concern about the construction of lines near residential areas, even in cases where the impact has been proven to be minimal;

- Landscape impact—damage to open spaces, the natural landscape, and heritage;

- Competition for land—power lines restrict land use, as well as the future development of residential neighborhoods.

The Statutory Planning Process

According to a 2012 Supreme Court ruling, 161 (high voltage) power lines require a plan and an environmental impact assessment, except for maintenance plans and minor upgrades. 400 (ultra-high voltage) lines require a National Outline Plan. 161 lines are also permitted under the authority of a district committee.

The time required to prepare the environmental impact survey is about two years. Recently, the system operator began engaging private planning firms to shorten the time required to prepare the environmental impact survey.

The planning process is characterized by uncertainty, coordination difficulties, and protracted processes:[11]

- Multiple planning institutions—plans are currently being promoted in several different frameworks: VATAL, the National Council, and the district committees. Lack of coordination between the various bodies results in a lack of a macro perspective, which leads to conflicts between plans and harms development efficiency.

- Difficulty synchronizing the planning bodies in the governmental decision-making process—the Minister of Energy and the Minister of Finance approve the development plans. After their approval, they are submitted to the planning bodies for approval, and the necessity of the projects is rediscussed. The planning bodies point to the importance of consultation in the early planning stages, in order to prevent later protraction of the process.

- Requirements for completing the environmental impact assessment, which were not included in advance in the guidelines for the assessment.

- The large number of entities required to address the plan for the purpose of coordination—specifically, approval is required from the Israel Nature and Parks Authority and the defense establishment. The process requires examining alternatives, including an underground alternative. The approval process may take between three and ten years.

- Coordination between the Israel Electric Corporation and Noga—the planning process requires coordination between the two companies.

- In the distribution segment, coordination is also required with the local authorities. The authorities need to allocate areas and coordinate the grid’s upgrade with the Israel Electric Corporation.

- Dependence between planning processes—one line is delayed until another is approved.

- Requirements for changes to line routes.

- A shortage of personnel at Noga—Noga is advancing multiple plans concurrently, and the numerous obstacles in each plan necessitates numerous coordination meetings and the involvement of senior company officials. The scope of human resources engaged in promoting the plans is inadequate, even though Noga relies on external consulting firms (such as Aviv).

- Some of the authorities that must address the plans during the approval process do not respond quickly enough and create a bottleneck in the process—specifically, Netivei Israel, the Israel Antiquities Authority, and Mekorot exhibit slow responses, which leads to longer plan approval times.

Undergrounding

In 2023, the energy minister set policy regarding the undergrounding of transmission lines. The policy determines that the lines will be placed underground in built-up areas (or areas designated for construction), where undergrounding is an engineering necessity, where it resolves a bottleneck in the grid, in the coastal environment, as well as in nature reserves and national parks.

In addition, the policy sets a quota for undergrounding transmission lines with a cumulative length of 50 km out of all the lines in the development plan.

Interviews conducted prior to the seminars held at INSS indicate that some of the opposition to the approval of additional grid lines could have been resolved by undergrounding additional lines.

Illegal Construction

In Israel, there is illegal settlement under the grid lines in the Negev region, the Sharon, Jerusalem, and the north of the country. The state is struggling to evacuate them, and related legal proceedings take a long time, which delays the construction of lines and electrical facilities. For example, the 100 km Eshkol-Negev line was not connected for three years due to delays in evacuating Bedouins.

Global Solutions to Grid Congestion

A report by the IEA presents grid congestion as a central challenge to the development of electricity sectors worldwide, particularly to the transition to green electricity.[12] According to the report, countries should consider system-level solutions to the grid challenge, including:

- Technologies to increase the capacity of the existing grid;

- Upgrading the existing grid with higher-capacity conductors (reconductoring);

- Raising the voltage level of the lines in order to increase the line’s capacity (voltage uprating). This solution was implemented in the Netherlands, where the voltage level of the lines was increased from 10 to 20 kilowatts. This change increased the capacity of the distribution grid lines fourfold;

- Dynamic management of the load on the lines using sensors, which monitor the actual load and allow for the optimal determination in real time of the possible load on the line (Dynamic Line Rating). This solution has been implemented in many countries, like in Belgium;

- Strengthening dialogue between grid developers, planning authorities, and developers, in order to identify future needs and constraints in advance;

- Information transparency for developers;

- Publication of updated informational maps that make it possible to identify areas where facilities can be connected to the grid. The maps will be updated frequently by the system operator and the distribution grid operator;

- The maps will detail restrictions and specific requirements for the facilities connected in each area. For example, restrictions on the hours of feed-in to the grid and on the hours of storage charging. The dates on which the restrictions will be lifted will also be indicated;

- Integrating solar installations and wind farms on the same connection in order to utilize the existing grid;

- Streamlining the planning approval process – increasing certainty regarding the planning requirements at the outset of the process, and shortening the process.

A review recently published by the consulting firm McKinsey indicates that the grid constitutes a major challenge to integrating renewable energy in numerous countries worldwide.[13] Key insights from the review include:

- Many countries face two main challenges in integrating renewable energy into the grid:

-

- Grid capacity does not meet demand—rapid development of capacity is required;

- The distribution grid is not prepared to manage decentralized production assets that have volatile production characteristics;

- Planning based on probable scenarios that reflect uncertainty regarding demand, production, and malfunctions. Identifying bottlenecks in the grid in light of the scenario analysis;

- Simplifying the process of submitting a connection application while clearly defining the requirements;

- Streamlining the equipment supply process for building the grid through partnerships with equipment suppliers and efficient supply chain management;

- Expanding access to real-time information about the status of the grid through digital tools and sensors;

- Improving the range of flexibility measures available to the system operator in order to address congestion events, such as demand management, production curtailment, and storage;

- Using advanced tools to manage the grid.

Systemic Solutions to Grid Development Barriers in Israel

Developing the transmission grid and making efficient use of the existing grid to connect renewable energy facilities may minimize the electricity sector’s susceptibility to damage to the gas infrastructure and to power plants, thereby making an important contribution to Israel’s energy security. Below is a range of solutions that will enable the expedited connection of renewable energy to the grid.

Updating the Development Plan

The transmission grid development plan was formulated based on a survey of renewable energy production potential prepared by Noga in 2022. It is recommended to update the plan in two key aspects:

- Integrating agrivoltaic production potential into the national potential map—In recent years, the importance of integrating solar production in agricultural fields (agrivoltaic) has been recognized, and the Planning Administration is currently preparing a National Outline Plan (NOP) for agrivoltaic facilities that will expedite the approval of plans for production facilities. It is proposed to integrate the potential areas for agrivoltaic facilities into the national potential map and to update the grid development plan accordingly;

- Integrating electricity-intensive facilities such as data centers near the potential areas, in order to reduce the need for grid development to connect the solar facilities.

Acceleration Plan to Approve the Grid Development Plan

Roundtable discussions during the seminars revealed a preference for orderly planning procedures over authorization procedures, in order to account for all the stakeholders affected by the grid’s development. However, the planning process must be regulated in a way that will prevent planning delays.

In light of this, it is proposed to formulate an acceleration plan to approve grid development plans, whose principles are:

- A subcommittee will be established at VATAL to approve grid development plans—the committee’s authorities and mode of operation will be determined in the Arrangements Law.

- The Ministry of Finance will allocate dedicated human resources to the committee.

- The committee will work toward regional approval of several lines concurrently in order to address the current situation, in which one delay holds up the approval of another line.

- The committee will define environmental requirements in advance.

- The committee will also be responsible for the building permit, in order to address the situation in which, after a plan is approved, the local committee delays granting the permit and stipulates it on further amendments to the plan.

- The committee will determine, for each plan, a preliminary decision (pre-ruling) on how to advance the plan. In the first stage, initial alternatives for line routes will be planned, and initial coordination will be carried out with stakeholders (the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, the Ministry of Transportation, and the infrastructure companies). After the initial coordination, the planning institution will issue guidelines on how to advance this, while addressing the main issues—plan or permit, undergrounding, preliminary route, and establishing a work plan until it goes into effect.

- The committee will define situations in which the planning process can be simplified and shortened:

-

- Easing environmental impact assessment requirements for underground lines.

- Expanding the plan’s blue line so that the line can be shifted as needed without delay.

- “Line for a line”—an expedited approval process in a situation where a new line is established tens of meters from an existing line.

- Shortening the process for planning changes within substations—replacing a transformer in an existing station with an exemption from a permit, and expanding an existing substation through an expedited process.

National Outline Plan (TAMA) 41—Upgrading Transmission Lines

The roundtable emphasized the importance of TAMA 41—a joint plan of the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, the Planning Administration, and Noga—that will enable transmission lines to be upgraded and replaced through faster planning, without the need for an in-depth examination of alternatives, which will reduce approval times and prevent restarting planning processes. The plan was approved by the National Council but not by the government, and it is recommended to approve it as soon as possible.

Expanding the Undergrounding Policy

The undergrounding policy approved by the Minister of Energy in 2023 allows the undergrounding of lines in built-up areas, in areas where the line could damage the landscape in the coastal environment and in nature reserves. A quota of 50 km was also set for the undergrounding of additional lines.

Currently, there is an option to underground 161-kV lines. Undergrounding 400-kV lines requires a technical solution to the challenges emerging from the construction of ultra-high voltage lines. Although undergrounding significantly increases the cost of building the grid, it enables other uses of the land and amends the current situation, in which electricity consumers do not bear the cost of affecting other land uses.

Due to the significant delay in approving overhead lines, the undergrounding of additional lines should be considered. The economic justification for additional undergrounding should be examined, among other things, also in light of its contribution to expediting the connection of renewable energy facilities.

Expanding the Service Charter of Entities Involved in the Planning Process

The service charter sets response times for an infrastructure company regarding plans that are promoted by other infrastructure companies. Government companies in the energy and transportation sectors are currently signatories to the charter. The charter should be expanded to include companies from the telecommunications sector as well.

Integrating Private Companies in Promoting Grid Lines

The 2018 electricity sector reform determined that the Israel Electric Corporation would be a monopoly with respect to the grid, so that grid infrastructure in the public domain would be built and owned solely by the Israel Electric Corporation.[14]

Some of the interviewees raised the possibility that the grid segments connecting renewable energy projects to the transmission grid would be constructed by private companies, and then transferred to the ownership of the Israel Electric Corporation. The lines will be built according to technical criteria set by the system operator, in order to ensure optimal integration with the existing grid. It was also proposed to allow private companies to assume responsibility for the statutory promotion of the various lines, subject to the system operator’s guidelines. Therefore, integrating private companies will make it possible to expedite connection to the grid without undermining the principles set forth in the reform.

It is proposed to allow private energy companies to serve as subcontractors of the Israel Electric Corporation for the purpose of grid development:

- Statutory advancement of lines by private companies;

- Construction of segments to connect energy projects to the transmission grid by private companies;

- Construction of substations by private contractors.

Maximizing the Existing Grid—Connection Criteria

The grid connection process is subject to approval:

- Connection to the transmission grid—the system operator’s approval.

- Connection to the distribution grid—the Israel Electric Corporation’s approval, in accordance with the limitations and criteria defined by the system operator.

The approval process requires risk management and an examination of situations in which the connection may harm the grid’s stability. Currently, the permissible load on the grid is determined with respect to two seasons of the year (summer and winter), taking into account the weather typical of each season. It is proposed to implement a dynamic criterion (Dynamic Load Rating) whereby the permissible load on the line will be determined on a daily basis, according to the weather conditions and the state of the line in practice.

This change in the permissible load policy on the lines, combined with the possibility of curtailing renewable energy installations on extreme days when the load on the line may damage the grid, will make it possible to connect additional installations to the existing grid even before the development plan is completed.

It is also proposed to consider temporary accommodations in the reliability criterion until the grid’s development is completed. This will make it possible to connect installations to the existing grid. In any case that raises concern for the grid’s reliability, the project will be disconnected from the grid without harming the electricity supply to consumers. This approach will make it possible to connect the facilities early on, subject to the producers’ consent to bear the financial implications due to possible disconnections of the facility.

Maximizing the Existing Grid—Technological Solutions

Implementing technological solutions (Grid Enhancing Technologies—GET) to improve load management on the grid may make it possible to connect additional installations on the existing grid. This includes:

- Engaging with international consultants and experts who will assist Noga in maximizing the connection to the existing grid;

- Using advanced conductors to increase the capacity of existing grid lines;

- Incorporating advanced sensors that will allow the Israel Electric Corporation and Noga to receive real-time information on the grid’s status, and manage the load accordingly;

- Distributed energy resources management systems (DERMS) as well as for monitoring and controlling the load on the lines, in addition to the technological challenge. Implementing this solution also requires coordination between the two management mechanisms currently in place:

-

- Supervising the transmission managed by the Israel Electric Corporation; supervision is also responsible for managing the distribution network.

- Noga’s operations system.

- Integration of storage facilities—using storage for load management;

- Upgrading existing lines—increasing the line’s capacity by replacing the conductors and increasing the lines’ voltage;

- Digitization of the grid—real-time data transfer for oversight of transmission, thereby enabling load management on the grid based on up-to-date information. This will make it possible to maintain a smaller reserve and enable connections to additional production facilities;

- Advertising up-to-date information to the public on the feasibility of connecting to the grid in various areas—in order to promote projects in areas where connection to the grid is possible;

- Advertising a “connection queue” that will allow developers to know how many megawatts are awaiting connection in each area.

Illegal Construction

Negotiations with the Bedouin and payment for temporary evacuation for the line’s connection period.

Barrier Removal Committee

Reestablishing the committee and holding periodic meetings.

The committee will enable mutual examination of barriers and delays in the approval of grid plans.

The meeting minutes will be advertised to the public.

Chapter 4: Microgrids as a Solution for Energy Security

Background

Throughout the years, electricity systems around the world were based on generation at large power plants, from which energy was transmitted to consumers via the transmission grid.

In recent years, three revolutions have been taking place in the energy sector (the three Ds):[15]

- The Decentralization revolution—energy is generated in the distribution network at low and high voltage, near consumers;

- The Decarbonization revolution—a shift from production at fossil-fuel power plants to production from renewable sources;

- The Digitization revolution—the development of computing and energy management capabilities.

At the same time, there has been a sharp decline in battery prices, so it is also possible to integrate storage capability into decentralized production systems, and ensure the supply of energy even when renewable energy sources are unavailable.

These trends create an opportunity to bring production closer to consumers and enable local management of demand, production, and storage, in order to reduce the need to “import” energy from the national grid and “export” surplus energy to the national grid. During routine, the local grid is connected to the national grid, but in extreme situations such as a security threat or an extreme climatic event, the local grid will also be able to operate disconnected from the national grid.

The development and promotion of microgrids may offer a variety of advantages to the electricity sector.

Advantages at the national level:

- Reducing the need to develop the transmission grid;

- Reducing the need to establish production capacity at the national level, by optimizing the use of energy generated at the local level;

- Increasing the proportion of renewable energy;

- Reducing outage minutes.

Advantages at the local level:

- Income from the sale of energy from local decentralized facilities;

- Energy security in emergencies;

- Lowering the cost of electricity through centralized purchasing for all demand on the local grid, according to the meter at the point of connection to the national grid.

Promoting microgrids raises social justice issues: The local grid enables groups in the general population to benefit from lower electricity prices, revenues from electricity generation during routine times, and energy security in emergencies.

In light of this, policymakers should examine whether the economic benefit of encouraging microgrids justifies supporting their construction. In particular, it is necessary to accurately quantify the benefit from reducing the development of the transmission grid and from savings in production capacity.

Microgrids Worldwide

The idea of microgrids first developed in remote areas where it was difficult to base supply on a connection to the national grid, including islands (such as Kodiak Island in Alaska, or the island of Eigg in Scotland) or remote frontier communities. In recent years, interest in microgrids has also increased at industrial campuses or universities (such as the University of California San Diego, Princeton University, MIT), which seek to base their entire consumption on green energy and guarantee their own supply reliability.

An example of an independent grid can be found at the Siemens campus in Vienna and on Kodiak Island in Alaska.[16] In addition to these, the possibility of microgrids in unique technological applications is also discussed in the professional literature, in particular:

- Maritime systems—such as large ships, or offshore gas and oil rigs;[17]

- Space stations—manned or unmanned;[18]

- Remote military bases;

- Mines at remote sites.

The Technological Challenge of Microgrids

A microgrid requires providing a local solution to balance the grid, instead of the distribution grid operator and/or the transmission grid operator, who are responsible for grid balancing under routine conditions,[19] including:

- Addressing load changes and frequency stabilization—The national grid operator is responsible for forecasting demand and adjusting production to demand. The grid operator is responsible for monitoring load changes in real time and responding to them by managing the production unit load and managing the demand. When the grid is managed independently, disconnected from the national grid, these changes must be addressed through production and storage assets connected to the local grid. This service may be particularly challenging with an independent grid, because the production and storage assets available to the local network operator are relatively few, and relatively small changes in demand—whose impact on the national grid is negligible—may result in a significant load change on the local grid.

Consequently, an independent grid may experience sharp changes in frequency; however, the impact of a frequency change in the local grid is low compared to the impact of a frequency change on the national grid, because there are no power stations on the local grid whose functioning could be affected by the frequency change.

- Low short-circuit currents—Low short-circuit currents in a local grid may lead to a slow response from the defense systems.

- Voltage stabilization and reactive power—Voltage drop in a microgrid is when the power system’s output voltage decreases as the load increases. The main reason for this is the resistance and electrical impedance of the lines, as well as the control response of the power converters in a decentralized system.

- Safety—In the event of a malfunction, an increase in voltage may occur that will pose a safety risk.

- Transition from grid-connected mode to islanded mode—The transition to islanded mode may cause the production assets in the local grid to disconnect from the grid (trip), and it will not be possible to meet the demand. It is therefore necessary to be able to smoothly manage transitions between operating modes, without compromising grid stability or supply to consumers.

- Protection—Systems are installed in the national distribution grid to protect against cyber threats and detect malfunctions and safety risks. When a local grid disconnects from the national grid, it may be left without sufficient protections and without adequate safety measures.

Possible solutions to the technological challenges include:

- Energy Management System (EMS) with suitable algorithms for managing decentralized production and storage assets, with real-time control of production and demand;

- Smart meters for real-time monitoring of production and demand;

- Implementation of improved droop control, which takes into account the load sharing among different sources;

- Smart Inverters /Grid Forming Inverters with voltage and frequency control capabilities;

- Fast Transfer Switches, which detect disconnection conditions and switch within milliseconds from online mode to islanded mode;

- Installing Virtual Synchronous Generators (VSG) – inverters that simulate the behavior of a synchronous generator and provide “virtual inertia”;

- Use of capacitors (in addition to storage systems) for voltage stabilization;

- Demand Control – control of the demand load in different areas in the independent grid in order to stabilize and balance the grid.

Feasibility of Microgrids in Light of the Electricity Sector Reform

Government Resolution 3859 concerning the reform in the electricity sector dated June 3, 2018 determined that the Israel Electric Corporation would be a monopoly with regard to the establishment, operation, and maintenance of the transmission and distribution grid in Israel. However, the resolution allowed the construction of a grid by private entities up to 10% of the scope of the distribution grid, in three situations:

- Historical distributors—Kibbutzim and Druze localities where the grid is not owned by the Israel Electric Corporation, and the responsibility for building, operating, and maintaining lies with a local distribution company;

- The East Jerusalem distribution company;

- “Land Divisions״/ campuses—a continuous private area where no public road passes through, including hospitals, universities, industrial centers, and factories. In these areas, the landowner may establish a local grid, production and storage assets at low and high voltage, and even sell electricity to consumers within the land division area without the need for distribution, production, or supply licenses. This excludes land areas where there is currently an Israel Electric Corporation grid, as well as residential apartments.

In light of this, microgrids can develop in Israel in two ways:

- An independent grid owned by a private distribution company, for example, on a kibbutz or in a private land division that will include production and storage assets and an energy management system;

- An independent grid owned by the Israel Electric Corporation, in which private production and storage assets will be built, and the Israel Electric Corporation will integrate a local energy management system that will enable the local grid to disconnect from the national grid in an emergency.

According to the Israel Electric Corporation’s approach, there is no impediment to encouraging microgrids; however:

- It is necessary to maintain what was agreed in the electricity sector reform, which states that the Israel Electric Corporation will be responsible for building the grid infrastructure in a public area, and for managing decentralized production.

- Generally, responsibility for building, operating, and maintaining the entire distribution grid should be left to a single professional entity (the Israel Electric Corporation) with economies of scale, which applies uniform and equitable standards for connection to the grid. This is the only way to guarantee an effective solution to the technological challenge in general and to large-scale decentralized production in particular, prevent conflicts of interest in connecting producers to a local grid, and a solution to operational and safety issues. According to this plan, competition will take place in the construction of production and storage facilities, but not in the construction of the grid.

- The interface between the distribution company and local grid management must be regulated by standards.

- The Israel Electric Corporation should be reimbursed for the additional cost that will be created due to the need to adapt the grid to work with local grids, in order to prevent cross-subsidization.

- The company is currently establishing DERMS (Distributed Energy Resource Management Systems). The full implementation of the system is essential to later enable local grid management, as well as real-time management of decentralized production.

- The company wishes to build its own storage facilities that will integrate into the local grid and which it will manage for the benefit of the entire sector, concomitant to the needs of the local community.

Microgrids in Buildings/Campuses

Building an independent grid in a building/campus is permitted by regulations. The following is required to enable independent operation of the grid in a building/campus:

- Independent production capacity on a scale similar to the building’s demand—in many buildings the roof area is relatively small and cannot meet the demand. Systems located on the buildings’ walls increase the scope of local production. However, the radiation on building walls is significantly lower than the radiation on roofs.

- Storage—storage systems adjacent to buildings require a building permit and fire department approval.

- Local energy management system—the technology’s maturity still needs to be demonstrated. The cost to the campus may reach approximately half a million NIS.

- Economic incentive—for energy demand management consumers, the gap between trough and peak enables economic viability for storage. In buildings or apartments billed under a flat rate, there is currently no incentive to install storage.

The Tel Aviv Municipality is leading this domain, particularly:

- A building permit for a new building in the city is granted subject to energy planning.

- The municipality aims to expand from smart management of buildings to smart management of the urban space as well.

Microgrids in Kibbutzim

The kibbutzim are preferred sites for microgrids. First, the grid in the kibbutz is owned by the local distribution company. Second, kibbutzim have a relatively high rate of local production using solar installations, and many kibbutzim also have emergency generators. In addition, some of the kibbutzim are located near the border, in areas where there is a security concern regarding the continuity of supply.

In Israel, microgrids were built at Kibbutz Shoval and at Kibbutz Ma’ale Gilboa:

- The grid at Kibbutz Shoval was successfully activated in several cases of power outages in the national grid.

- The grid at Kibbutz Ma’ale Gilboa was developed as part of a pilot in cooperation with the Israel Electric Corporation to examine the interface between a distribution grid and a local grid.

The main challenges in establishing an independent grid in kibbutzim are:

- Technological challenge—the technology for independent management of the grid is not fully developed yet, and therefore a continuous supply of electricity in emergencies is not guaranteed.

- Feeding surplus into the grid during routine—establishing solar capacity at a scale that meets regular needs results in the kibbutz feeding surplus into the grid during routine, when the grid is not operating in islanded mode. Thus, the national grid must be developed in a way that will enable absorption of the surplus.

- Permits for building storage—only small storage facilities are exempt from a permit.

- Lack of an economic incentive to establish an energy management system—production and storage facilities have an economic incentive through tariffs (for low-voltage facilities) and a market model (for high-voltage facilities). In contrast, the energy management system has no economic value under routine conditions, and there are no economic arrangements that incentivize the investment in and establishment of these systems.

- Israel Electric Corporation control of high-voltage production facilities within the distributor’s grid—Current regulation requires installing communications equipment to production and storage assets in the distributor’s grid, in order to enable the dominant distributor (the Israel Electric Corporation) to control these assets. Establishing an independent grid requires coordinating control of the facilities.

- Lack of regulation for discharging energy from an electric vehicle (Vehicle-to-Grid, V2G)—Many kibbutzim house electric vehicles and charging stations, but there is still no V2G regulation.

Microgrids in Cities and Moshavim

The distribution grid in cities and moshavim in Israel is owned by the Israel Electric Corporation. Many localities have installed solar systems for electricity production, but unlike the kibbutzim, solar generation usually constitutes a relatively low proportion of local demand.

The Israel Electric Corporation is in an accelerated process to procure a DERMS (Distributed Energy Resources Management System). The system is meant to address the proliferation and complexity of renewable energy on the grid, and is expected to enter into service within the next two–three years. However, the system is not designed to enable independent islands, and it constitutes part of the national grid.

Alongside this, “kosher electricity” systems are being promoted in several cities in Israel, which will enable disconnection from the grid on Shabbat or a holiday and a local supply of electricity from a storage system. Meanwhile, the Israel Electric Corporation is promoting the establishment of a storage system in Bnei Brak with the option of disconnecting a neighborhood from the grid on Shabbat as part of a solution for “kosher electricity.”[20]

According to the government resolution, the Electricity Authority is expected to publish standards that will enable the disconnection of a local grid, but they have not yet been published for a public hearing.

Recommendations

Microgrids are a possible solution for the energy security of border communities, neighborhoods, and campuses in Israel. The feasibility of building the grids has improved in recent years in light of the broad deployment of renewable energy facilities and storage facilities, and the development of energy management systems.

In addition to the local benefits, microgrids may also help reduce the need to develop the transmission grid and generation capacity at the national level.

In light of the benefits and barriers that were mapped, it is recommended to consider:

- A quantitative analysis of the economy-wide benefit of building microgrids. The analysis will form the basis for setting government policy for microgrids, and make it possible to establish the need and the sector-wide feasibility of providing incentives for this field.

- Regulating the interface between the Israel Electric Corporation and the local management system in cities and moshavim through standards and tariffs to be set by the Electricity Authority. The Israel Electric Corporation will still own and operate the grid. The regulation will allow the Israel Electric Corporation to disconnect a moshav or a neighborhood if necessary, and to supply the energy from local production and storage assets.

- Promoting technologies for managing microgrids, such as through grants from the Chief Scientist at the Ministry of Energy. This includes grid management systems, safety measures, voltage stabilization measures, and more.

- Promoting national pilots for microgrids, in cooperation with the system operator and the Electricity Authority, which will examine technological and regulatory models for managing flexibility, storage, and demand in real time. These pilots, particularly in remote areas and in community resilience centers, will provide a basis for operating independent local grids during emergencies and for building a smart, flexible, and decentralized electricity grid in Israel.

- Subsidizing energy management systems in communities where there is a risk of disruption to the electricity supply during emergencies, subject to an economic review of alternatives to ensure energy security for border communities: generators, undergrounding lines, an independent grid with local production, storage, and management capabilities.

- V2G regulation, enabling energy discharge from the batteries of electric vehicles to the grid, in order to provide an additional energy source for the grid during emergencies.

- Regulation of feeding surplus energy to the grid during routine—the regulation will enable communities to establish additional renewable energy facilities, in order to allow for sufficient production according to the expected demand during emergencies.

- Encouraging the use of smart inverters that enable off-grid operation during emergencies (Grid Forming).

- Enabling areas connected together on a local grid (such as neighborhoods or cities) to purchase electricity collectively from a private supplier—implementing the Community Choice Aggregation model, which will allow for collective purchasing, while allowing individual consumers to purchase energy separately from the local community. This implementation, coupled with the integration of storage systems into the local grid, will enable more efficient load management and reduce energy costs for consumers.

__________________

[1] World Energy Outlook 2025.

[2] The delivery system includes the transmission grid and the array of switching stations and substations.

[3] Electricity Authority, Oversight Reports for Quarter 3–4, 2024, dated January 8, 2025.

[4] US Department of Energy, Microgrid Overview (2024).

[5] Tariff-based regulation for low-voltage facilities and a market model for high-voltage facilities.

[6] International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2025.

[7] Ronit Zilberstein, “48 Degrees and Without an Air Conditioner: Soldiers in the South Were Sent Home Because of Extreme Heat,” [in Hebrew] Israel Hayom, August 14, 2025.

[8] Gad Lior, “Severe Heat Wave: All-Time Record Broken in Israeli Electricity Consumption,” Ynet, August 10, 2025.

[9] Nir Hasson, “Heat Wave Sparks Record Temperatures and Wildfires Across Israel,” Haaretz, May 17, 2025.

[10] Electricity Authority, Concentrated Status Report for 2024 [in Hebrew].

[11 Inter-Ministerial Team, Expediting the Deployment of the Electricity Transmission Grid (September 2023).

[12] International Energy Agency, Building the Future Transmission Grid (2025); International Energy Agency, “Grid congestion is posing challenges for energy security and transitions” (March 25, 2025).

[13] “How grid operators can integrate the coming wave of renewable energy,” McKinsey & Company (February 8, 2024).

[14] Except for the areas of historic distributors and the East Jerusalem distribution company’s area.

[15] Stephen L. Prince, “Determining Direction: The Three Ds of an Energy Sector in Transition,” Energy Storage News, April 12, 2017.

[16] A. Clamp, “Microgrid with Energy Storage: Benefits, Challenges of Two Microgrid Case Studies,” NRECA

[17] Zheming Jin, Giorgio Sulligoi, Rob Cuzner, Lexuan Meng, Juan Carlos Vasquez Quintero, and Josep M. Guerrero, “Next-Generation Shipboard Dc Power System: Introduction Smart Grid and DC Microgrid Technologies into Maritime Electrical Networks,” IEEE Electrification Magazine, 4 no. 2 (2016): 45–57.

[18] Luca Tarisciotti, Alessandro Costabeber, Linglin Chen, Adam Walker, and Michael Galea, “Current-Fed Isolated DC/DC Converter for Future Aerospace Microgrids,” IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 55 no. 3 (2019): 2823–2832.

[19] Moslem Uddin, Huadong Mo, Daoyi Dong, Sondoss Elsawah, Jianguo Zhu, and Josep M. Guerrero, “Microgrids: A Review, Outstanding Issues and Future Trends,” Energy Strategy Reviews 49 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2023.101127

[20] Government Resolution 490 dated May 7, 2023 regarding Promoting Reliability of Electricity Supply in the Urban Area through Storage, Kosher Electricity Services and Amendment of a Government Resolution.

Part A

Chapter 1: The Climate Crisis as a Challenge to National Security and to the Electricity System in Israel | Galit Cohen and Gal Shani

Part B

Chapter 3: Developing the Transmission Grid for Connecting Remote Renewable Energy Facilities to Israel’s Electrical Grid