The Israeli System: The Challenge of an Ongoing Crisis to National Security Foundations

Meir Elran, Shmuel Even, Carmit Padan, Moshe Bar Siman Tov, Ephraim Lavie, Pnina Sharvit Baruch, and Tomer Fadlon

Snapshot

Deeper socioeconomic gaps, in light of the pandemic · Weakened state institutions and systems · Reduced social solidarity, public trust in institutions, and ability to decipher reality · No state budget

The Israeli System: The Challenge of an Ongoing Crisis to National Security Foundations

Meir Elran, Shmuel Even, Carmit Padan, Moshe Bar Siman Tov, Ephraim Lavie, Pnina Sharvit Baruch, and Tomer Fadlon

Recommendations

Professional management of the COVID-19 crisis · Passage of state budget and launch of a socioeconomic recovery program · Preparations to grapple with non-security crises

The multilayered COVID-19 crisis – comprising health, economic, social, and governmental dimensions – continues to evolve in the context of much uncertainty, weakens national coping capabilities, and as such harms national security. In Israel there are two elements that amplify the damage of the COVID-19 pandemic: the constitutional-political crisis and the centralization of the public system. These harm governmental legitimacy, form cracks in the contract between the public and the leadership, and erode the ability to cope with the pandemic and its consequences. How the pandemic was handled undermined public confidence in the government, hurt social solidarity, punctured economic strength, and challenged civilian enlistment in the struggle against COVID-19, and therefore disrupted the functional continuity of national systems. The serious consequences of the pandemic will continue in 2021 along with the vaccination process. Even if the pandemic gradually subsides in the second half of 2021, its deep socioeconomic consequences will accompany Israel into 2022.

Basic Assumptions

This assessment of Israel’s internal arena focuses on the multilayered mega-crisis that has developed in Israel and worldwide as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. At issue is the convergence of health, economic, social, governance, and political crises underway in Israel over the past year. The multiple facets of the crisis and uncertainty about the present and the future disrupt normal life, and accelerate the reciprocal damage among these elements. All of this significantly weakens Israel’s national resilience, and impacts negatively on national security. At the same time, the start of the mass vaccination campaign provides grounds for guarded optimism about the dissipation of the crisis by the end of 2021.

In analyzing the effects of the multifaceted crisis on Israeli society, it is necessary to distinguish between socioeconomic ills that were present before COVID-19, which the crisis exposed and aggravated, and those created by the pandemic itself. The damage caused by the pandemic is severe but differential; it is particularly harmful to specific groups, primarily the lower middle class, small business owners, and people living in poverty.

The characteristics of the crisis in Israel and the ways it has been managed are similar to those in other Western democracies. Yet two interrelated areas have aggravated the damage in Israel: the prolonged political crisis, and the high degree of centralization of the already weak public institutions.

The political crisis exacerbates the damages from the pandemic. Prime Minister Netanyahu and Alternate Prime Minister Gantz

Photo: Amos Ben Gershom/Knesset Spokesperson’s Office/Handout via REUTERS

The political crisis has spawned system-wide paralysis and obstructed vital decision making processes, undermining public trust in government and hampering the sense of solidarity among various groups in Israeli society. It has limited the level of societal commitment that is needed for a concerted effort to halt the pandemic. The highly centralized public services such as the health, education, welfare, financial, and law enforcement systems are often hard-pressed to provide essential services to the public. This problem is partly due to the severity of the current challenge, but it is further exacerbated by the structural weakness of the public service institutions themselves, the bureaucracy, the competition between them, and their growing politicization, which in turn has further increased the centralization. Many in Israel are distrustful of the central government and its institutions, and doubt their collective commitment to public needs. Their legitimacy has waned, fracturing the basic covenant between the public and government, and spurring a downward spiral in the capacity of the central government to manage the crisis and its consequences. One prominent example of this is the prolonged absence of a state budget.

The picture emerging after nearly a year of coronavirus in Israel raises a question about the severity of the long-term consequences of the crisis. There are still no clear answers to this question, as uncertainty precludes a full understanding of the crisis and an ability to assess its far-reaching consequences. Various basic assumptions have generated contradictory scenarios on what lies ahead. We posit the following:

- The pandemic and the three general lockdowns imposed to date have created severe disruptions that harm national resilience (affecting solidarity, civil engagement, trust, hope, and economic sustainability). This damage impedes the state’s performance and functional continuity, which is needed to manage the ongoing crisis.

- A critical benchmark in a situation assessment is once a majority of the population has been vaccinated. The process of administering the vaccines to the public is expected to continue for a number of months, which includes the third lockdown and yet another round of Knesset elections. Both these developments are bound to worsen the socioeconomic situation, and this downturn will likely persist for most of 2021. Only afterwards does a gradual process of recovery and growth stand to begin, with a weak starting point of the national systems.

- Successful recovery depends on political stability, functional capacities of the public institutions, a state budget, rigorous planning, and strong advance preparations. So far, none of these have even begun (for example, there is no national plan for mass professional training).

In March 2021, Israel will go to the polls for the fourth time in two years, but it is highly questionable whether forthcoming elections will end the ongoing political crisis.

The Healthcare Dimension

The most prominent feature in most or all of 2021 will likely be the ongoing uncertainty about the pandemic and the numerous possible scenarios it may generate. There are still no answers to a number of key questions, each of which can have a substantial impact on future developments.

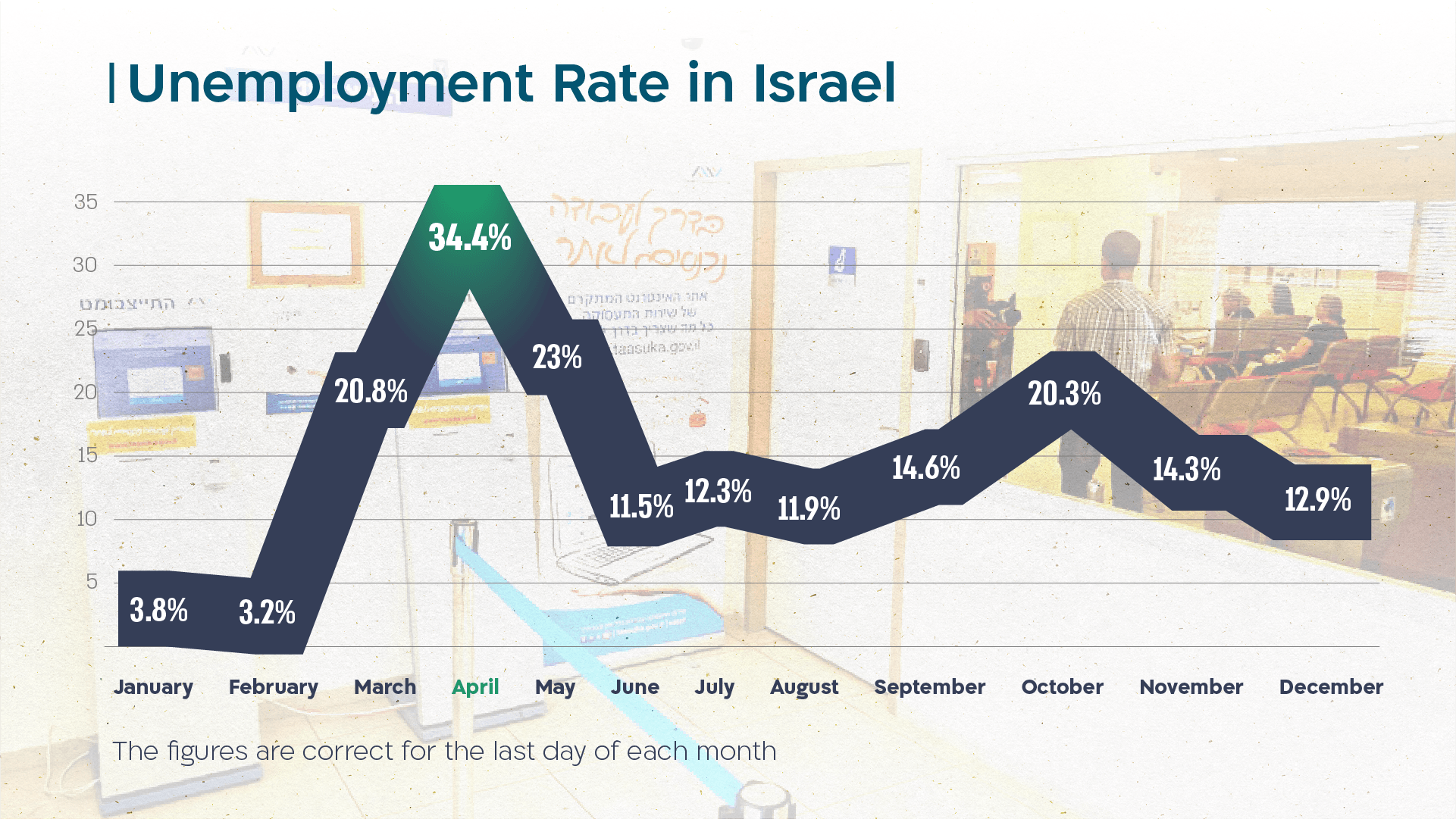

The successful development of vaccines and the launch of their worldwide distribution, as well as the beginning of vaccinations in Israel, are excellent news in the health and economic spheres. Nevertheless, even on the optimistic assumption that vaccination will proceed quickly and most people will be vaccinated, it is still likely that many in Israel’s population will go through the coming winter unvaccinated, and that increases in morbidity will require further significant restraining measures. Thus while the seasonal influenza may prove to be fairly mild this year, the patterns in at least half of 2021 will likely be similar to what we have experienced so far, including the potential for a rapid and extensive spread of the pandemic requiring active preventive measures.

Even after the virus is eradicated, its severe consequences will persist for many years into the future. The government and society thus need to make the necessary preparations, both for a persistence of the pandemic and for the post-pandemic era, while also preparing for other future risks.

The Economic Dimension

Most of the damage to the Israeli economy has been caused by the pandemic and by the government’s mismanagement of the economic crisis, but the pandemic’s effects on the global economy have harmed Israel as well. According to an October 2020 forecast by the Bank of Israel, Israel’s GDP will shrink from its 2019 level by 5 percent in 2020 in an optimistic scenario, and by 6.5 percent in a pessimistic scenario. The optimistic scenario assumes no further large-scale lockdowns. The Ministry of Finance’s forecast (November 29) predicts a 5 percent decrease in GDP in 2020. According to an October forecast by the International Monetary Fund, Israel’s GDP will fall by 5.9 percent in 2020, about the same as in other developed economies, and the rate of growth in 2021 will be 4.9 percent. Third quarter results in Israel, published in November 2020, show that the effect of the second lockdown on the economy was smaller than expected. Bank Leumi predicted (November 22) that GDP would drop by only 3.4 percent in 2020.

As of mid-December 2020, the 2020 budget had not yet been approved, and the state budget for 2021 was not even prepared, mainly due to political reasons. Israel also has no economic plan to accompany the budget. This is one of the main failures in economic management, compounded by the bureaucratic chaos in the Ministry of Finance, reflected in the many personnel changes in the Ministry’s top ranks. In effect, the government is operating primarily in a reactive mode and lacks a comprehensive perspective, improvising with measures such as supplements to the 2019 budget and other arrangements. According to August 2020 Ministry of Finance assessments, the budget deficit in 2020 will reach over 14 percent of GDP compared to 3.7 percent in 2019, and the ratio of debt to GDP will amount to 80 percent of GDP, compared to 60 percent in 2019. Restoring this index to its previous level will take many years.

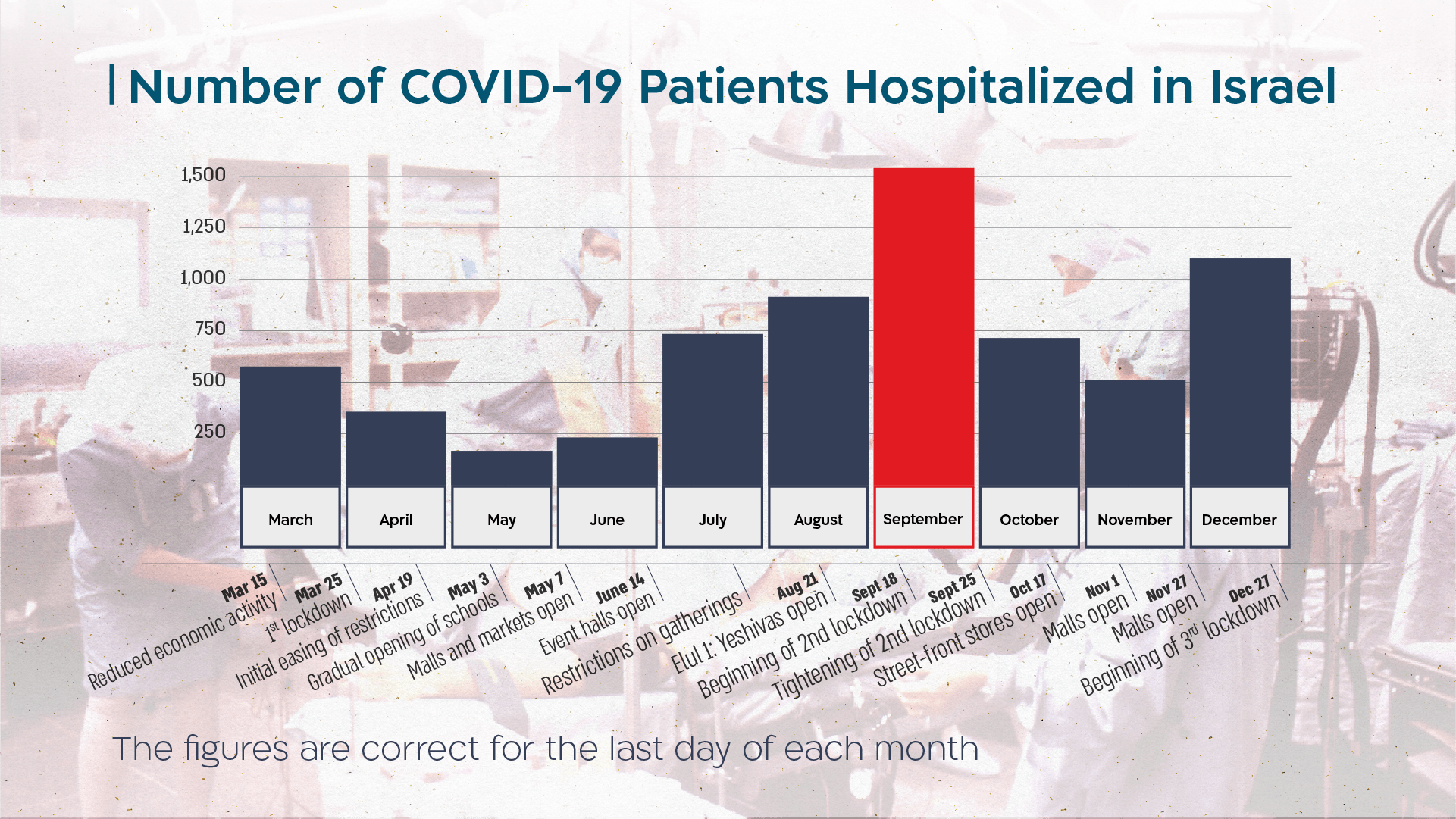

One connection between the economic and the social crises is the unemployment rate (people unemployed or on unpaid leave), which in October, during the second lockdown, stood at 20.3 percent of the labor force. In October the Bank of Israel predicted that according to this broad definition, unemployment would reach 16.7 percent of the labor force at the end of 2020 in an optimistic scenario and 20.2 percent in a pessimistic scenario, although the negative impact on Israelis is not even and certainly not uniform. Thus far, public sector employees have not been affected. The magnitude of the blow to labor security and wellbeing has been especially severe for the middle class (income deciles 3-6) and people under the poverty line; the economic situation of many of the working poor has deteriorated. Particularly hard hit are employees in the private sector – internal tourism, entertainment, leisure, and restaurant sectors – and small business owners. Furthermore, the performance of essential social institutions, such as the education system and civil society organizations, has been damaged. This has a deleterious effect on employment and on the training of young people, and the damage is liable to be long term. In order to support people and businesses, the Ministry of Finance is operating an assistance program, including payments to employees on unpaid leave until June 2021.

On November 13, 2020, despite the economic situation, the S&P credit rating agency approved an “AA- credit rating with a stable outlook” for Israel. S&P emphasized that Israel is a sound economy with a flexible monetary policy. The main limitations on the rating remain the high debt burden and the geopolitical risks. On December 4, Moody’s approved an “A1 stable” rating for Israel, after downgrading it from “A1 positive” of April 24

2021 Economic Forecast

The magnitude of the economic crisis is primarily a function of the healthcare crisis. The success in developing vaccines and their global distribution are likely to reduce the degree of uncertainty about the duration of the economic crisis. The effects of the multifaceted crisis in Israel, however, also depend on the political situation and how this crisis is handled. In the short-to-medium term, this involves the ability to manage the economy with a minimum of general lockdowns. In the medium-to-long range, it entails the ability to stabilize and accelerate the economy after the end of the pandemic. Preparations for this should be made now, for example, by retraining workers in large numbers and investing in education and relevant infrastructure, such as digital national systems.

The Bank of Israel’s October 2020 forecast for 2021 predicted a GDP growth of 6.5 percent in an optimistic scenario and only 1 percent in a pessimistic scenario. According to this forecast, the unemployment rate at the end of 2021 will be 7.8 percent in an optimistic scenario and 13.9 percent in a pessimistic scenario. The budget deficit projections are 8 and 11 percent of GDP, respectively.

The Bank of Israel makes it clear that both scenarios, optimistic and pessimistic, rely on probable parameters, and even more extreme scenarios are possible. This wide range illustrates one of the problems with these forecasts. Another problem is that the forecasts are presented according to calendar years, with no connection to the duration of the pandemic. Rather, economic scenarios based on the expected progression of the pandemic – both before and after the mass vaccination – are preferable.

The momentum from the outset of the vaccination campaign in Israel raises the hope that the more optimistic scenario will prevail. Nonetheless, Israel needs strong economic management, which requires a state budget and an economic plan that will lead to growth in the coming years. As of now, there is no governmental body below the cabinet level that coordinates the crisis in an integrated manner beyond the healthcare level; such a body should be created. It is also necessary to provide the government ministries with a budget that will enable governmental assistance to people and businesses that have been severely hurt by the crisis, rather than distributing it equally to everybody. As long as the health crisis continues, government policy should take into account both health and socioeconomic needs based on cost-benefit considerations. For example, more leniencies should be shown toward opening businesses that make large contributions to the GDP and/or to employment while incurring relatively low health risks, such as the hi-tech industry, services with no office hours, and businesses in open spaces such as agriculture and construction. Also, digital operation of the economy should be expanded.

At the same time, the government should continue to provide a safety net for people whose livelihood has been adversely affected, assist economic sectors that have suffered losses, and encourage employees and self-employed people to undergo professional retraining. It is important to institutionalize an alternative model for compensation of unpaid leave. Substantial evidence shows that the current model creates an incentive for people to resist returning to work, including young employees taking their first steps in the labor market. The current situation is liable to cause long-term damage, with employees growing accustomed to government assistance instead of wages. There are alternative models for keeping active labor relations between employees and employers intact.

The Societal Dimension

Israeli society is heterogeneous and polarized. Wide gaps and differences between the various social groups are reflected in political disputes and exacerbated by struggles for positions of influence and distribution of resources. The pandemic and the multifaceted crisis have exposed and aggravated these conflicts to the extent that social solidarity has been undermined. However, good relations between the various groups are essential to management of a national crisis, as society’s ability to cope with major disruptions depends on the relations among its components.

The social harm resulting from the pandemic has numerous manifestations, led by:

- Social division and polarization: The nature of the relations and the degree of solidarity between different parts of society are important factors in shaping society’s trajectory. In the first wave of the pandemic there was a decided trend of groups joining together for the sake of a shared purpose. This trend subsequently ebbed, however, mostly because of the problematic management of the crisis. A sense of helplessness has led some groups to distance themselves from others they perceive as threatening. Such sentiments reinforce adherence to the core values and identity of the group, inflaming relations between sectors and raising hostile discourse toward other groups, such as ultra-Orthodox Jews, Arabs, and anti-government demonstrators. The social protest is further evidence of the existing social division, reflected in the divergent demands of the various groups of demonstrators, while the political leadership is perceived as fanning alienation and hostility between them. In turn, the public discourse is not conducive to joining forces: the social struggles preclude creating a shared basis for public action; instead of solidarity, polarization becomes more extreme. The divergent demands by protest groups indicate that the crisis of trust has emerged not only in the face of the current political leadership and the economic distress, but extends to the systemic governmental and socioeconomic structure in Israel.

- Differential effects: While the crisis has a severely adverse effect on the Israeli public in general, some sectors are worse off than others. The highest morbidity rates are in the ultra-Orthodox and Arab communities. The economic damage is strongest in the lower middle class and among people living in poverty. Senior citizens, half of whom live alone, have been hit very hard. Violence within the family, especially toward women, has risen. More women than men have been pushed out of the labor market, and most of the calls for emotional support have come from women. The pandemic’s extended duration has intensified pressure and anxiety. According to a November survey from the Central Bureau of Statistics, 37 percent reported a feeling of stress, while 30 percent indicated that their state of mental health has worsened.

Since May there has been a sharp ongoing decline in public trust in the leadership. Demonstration near the Prime Minister’s residence in Jerusalem

Photo: Alex Eidelman / Shutterstock.com

- Multi-system crisis in public trust: Leading the public in the struggle against the pandemic requires trust on many levels – between the public and the leadership, among the different sectors of society, and within the political system. Currently in Israel, all of these leave much to be desired. According to a range of surveys conducted since May, public trust in the political leadership, especially in the Prime Minister, has plummeted, primarily due to failures in leadership, management of the crisis, and credible communication with the public. This has resulted in a rupture of the bond between the leadership and the public. Large parts of the population believe that the crisis is managed on the basis of political, coalition, and personal interests rather than the good of the public. This detracts from the public’s trust in the leadership, which in turn affects the ability to mobilize the public for the joint struggle against the spread of the pandemic.

Overall, the ability of public institutions in Israel to function in this major crisis has been severely disrupted. Still, there is also room for cautious optimism, mainly due to the massive distribution of the vaccine, which raises hope for the termination of the acute crisis by year’s end.

The Arab Society

As part of Israeli society, the Arab public and its leaders were mobilized for the struggle against the pandemic, and medical personnel from Arab society have stood at the forefront of the national effort against the virus. Initially the sector acted as a collective, cooperating with the government ministries and security forces, and weathered the first wave of the pandemic with low morbidity. However, since the second wave the situation has deteriorated, with the percentage of Arabs infected by the disease double their percentage in the population. The causes were growing indifference among the Arab public, coupled with economic hardship, lower state provisions, and a continued wave of violence and crime.

Moreover, the Arab public is in the throes of an acute political crisis. On one side is the Joint List, which traditionally embraces a cautious position on integration with Israeli society and the political establishment, both due to an entrenched ideological position and the lack of legitimacy in Jewish society for such integration. On the other side are growing parts of the Arab public, mainly in the middle class, which are interested in increasing integration in Israeli society. They demand that their leaders in the Knesset find a way to harness their political power to promote essential Arab interests. This clash could lead to a breach in that society’s political structure, culminating in the dissolution of the Joint List – a process that has already begun.

The COVID-19 crisis has created opportunities for changing the Jewish majority’s attitude toward Arab society, which met state expectations during this acute crisis, at least initially, and for realizing Arab aspirations for greater integration in Israel’s national life. It is likely that despite the difficult political, economic, and social state of Arab society, which could also lead to increased violence, there is now an opportunity to improve relations between the majority and the minority, provided that two main conditions are fulfilled.

The first is the advancement of the existing trend toward integration of Arab society in the general Israeli economy and society. This entails the furtherance of long-range development plans (primarily the introduction of stage 2 of Cabinet Resolution 922 relating to the socioeconomic growth of the Arab population). This must be complemented by new projects to enhance economic and social growth of the Arab sector following the present crisis, and implementation of plans to curb the growing violence and crime within the Arab society. The second condition is recognition by the Zionist parties of the legitimacy of the Arab vote, and Jewish-Arab cooperation on civil matters.

The Military Dimension

The perceived weakness of civilian agencies during the pandemic bolstered public calls for the IDF to participate in managing the crisis. The IDF thus finds itself involved in the national campaign against the pandemic, mainly through the Home Front Command. It has performed a broad variety of missions, among them assisting local authorities and civilians in distress, as well as working in various projects to contain the morbidity (e.g., COVID-19 hotels and contact tracing). At the same time, the military is subject to political pressure and is criticized in the media for its actions, even while refraining from taking overall or even local responsibility for managing the campaign against the pandemic. At the same time, the IDF must preserve operational and logistic capabilities in order to fulfill its ongoing security responsibilities.

IDF involvement in managing the crisis stemmed from a weak civilian system. Home Front Command activity during the crisis

Photo: IDF Spokesperson (CC BY-NC)

Beyond the diversion to civilian tasks related to the pandemic, the crisis has a clear adverse impact on IDF force buildup and operational readiness. In addition, the political environment has generated conflicting pressures on public institutions and watchdogs, including the IDF; there are rapid senior-level changes in the Ministry of Defense; there is the lack of a government decision concerning the approval of the Tnufa (Momentum) five-year plan for the IDF; absence of a state budget; and an accelerating decline in motivation to serve in the IDF, including in combat units. Half of the Israeli public (51 percent, according to a November survey by the Israel Democracy Institute) believe that the IDF is economically inefficient. Even if these aspects have minor short-term consequences, they might have harmful effects on the regular framework needed for IDF force buildup to allow it to meet future challenges.

The Democracy Dimension

The COVID-19 crisis began at the height of two interrelated crises, constitutional and political, involving ongoing erosion of democratic values and attempts to weaken the power of gatekeepers in and out of government institutions. Additional manifestations of this development are the growing practice of ignoring professional staff proposals, preference for political interests without consideration of the rules of proper management, and undermined foundations of democratic discourse, which naturally tends to be divergent.

The need to stop the spread of the pandemic has led to an unprecedented suspension of basic rights and freedoms in the framework of emergency legislation, some of it with no parliamentary supervision. The Israel Security Agency and the IDF have been called to monitor Israeli citizens, and the government is wielding extraordinary powers, with potentially dangerous implications for Israel’s democracy.

As a rule, the supervision and control mechanisms, headed by the courts and the Knesset, continue to play an important role in overseeing the government and restraining its actions, despite repeated attacks on gatekeepers, especially the courts – attacks that have greatly increased since the beginning of legal proceedings against the Prime Minister. The replacement of an objective discourse about the proper limits to judicial intervention with adversarial and politically motivated rhetoric raises concerns that watchdogs are exercising excessive defensive self-restraint, and that this will increase in the future, with a dangerous tipping of the balance of power and authority between the branches of government.

The voices heard in the United States advocating disruption of the transfer of government should arouse concern in all democratic countries, including Israel. There is hope that Biden’s entry into the White House will halt the rise of worldwide demagogic and anti-democratic forces, which enjoyed support during the Trump presidency. That would also influence the state of democracy in Israel, because the more importance is attributed to democratic values in the global environment, the more likely Israel is to respect them, including in its own territory.

Policy Recommendations

Despite the commencement of the mass vaccination campaign, uncertainty is likely to prevail in 2021. Even assuming that the COVID-19 pandemic gradually subsides, its consequences will be felt for a long time. Israel will face major challenges in the first half of 2021 resulting from a possible combination of new waves of infection; various degrees of lockdowns and their effects, which are expected to be severe; and an ongoing political crisis, with a fourth round of elections in two years, followed by what will likely be difficult negotiations to form a coalition.

Even if the pandemic gradually dissipates during the second half of 2021, the ramifications of the multifaceted crisis, especially its economic and social aspects, will still be strongly felt in and likely beyond 2022, given the heavy economic costs of the crisis and the way it was handled, the continued weakness of Israel’s public institutions, and the damage inflicted on large sectors of society – people living in poverty and the lower middle classes, particularly in the private sector. The national recovery effort will require a significant change in multiple domains: major public engagement and mobilization of a deeply polarized society, far more professional and efficient government management, and a political leadership focused on economic and social growth. All of these require comprehensive structural changes in general, and in the political establishment in particular.

Even if the pandemic is gradually contained, its consequences will be felt for a long time. Prof. Ronni Gamzu, head if Ichilov Hospital and formerly the coronavirus czar, receiving the vaccine

Photo: REUTERS/Ronen Zvulun

At least in 2021, Israel will be much weaker as a country and a society than in early 2020, and as such, the level of national security will be lower than before the pandemic began. Even if economic recovery takes place in 2021, social recovery will be slower and more gradual, so that before 2022, Israel will likely not regain the socioeconomic levels it enjoyed in early 2020. The economic situation will also impact on the security realm.

This analysis invites several principal system-wide recommendations:

- For the short term (2021): A focus on improved professional management of the multilayered crisis; passage of a budget and an economic plan featuring high priority for investment in civil affairs and disadvantaged groups, and thorough preparations for the expected stage of recovery and growth following the crisis; a clear priority for the public health domain aimed at curbing morbidity (including additional lockdowns), based on differential perspectives (backed by trajectories of local infections), alongside strict enforcement and public messaging directed to different groups; priority for keeping the school system open, in accordance with the necessary restrictions; less politicization in the public sphere; and better preparation for extreme scenarios of a possible spread of the pandemic.

- For the medium range: A concentrated national effort aimed at economic growth and social recovery, with a focus on expanding and diversifying employment and empowering the education system; renewed consideration of Israel’s strategic response to changes in the regional theater; formulation of a national consensus on a new agenda in civil, social, and political matters that will be shared by all groups in the country, to include governmental decentralization and the strengthening of local governments; formulation and implementation of insights for the post COVID-19 period; and better preparation in the civilian sphere for civil and military crises.