2021 Strategic Overview: Vaccines and Vacillations

Itai Brun and Anat Kurz

Snapshot

Great Power competition, with the pandemic in the background · Further normalization in the Middle East · Iran remains the primary threat · A weakened Palestinian system looks to Biden · Unwanted escalation possible · Internal crisis challenges Israel’s democratic foundations

2021 Strategic Overview: Vaccines and Vacillations

Itai Brun and Anat Kurz

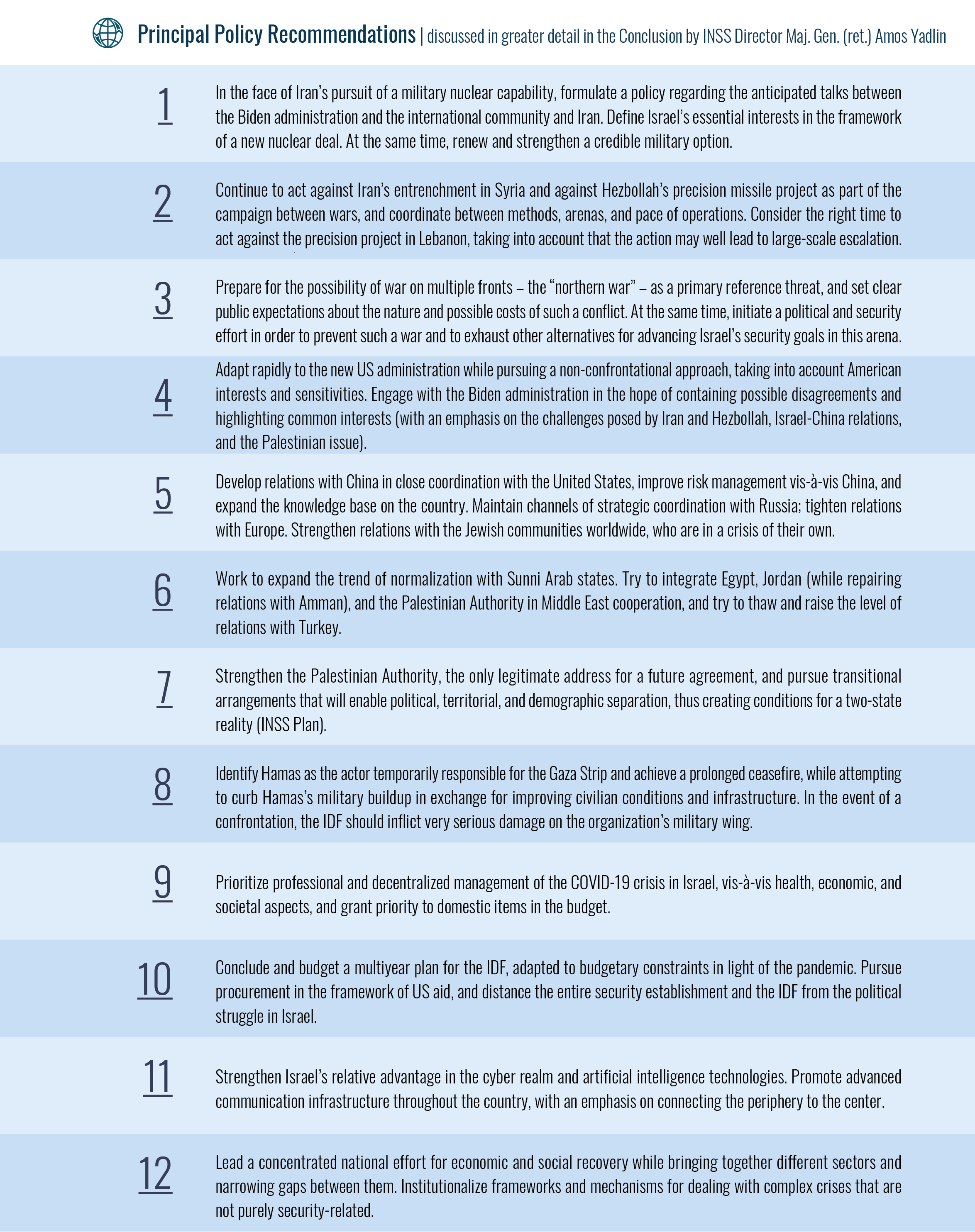

Recommendations

Prioritize attention to internal crisis, without neglecting external challenges · Coordinate with the Biden administration, particularly on Iran · Further normalization · Prepare for escalation in the north and in Gaza · Share expectations with the public on what the next war will demand

The strategic assessment for Israel for 2021 is shaped by significant uncertainty in three principal areas: the level of success in coping with COVID-19; the modus operandi and policies of the new administration in the United States; and the political developments in Israel. The current assessment is based on a broader conception of national security, which places greater weight than in the past on the domestic arena and on threats to internal stability, social cohesion, values, and fabric of life. This of course does not detract from the urgency of security threats, which remain significant. In the face of this uncertainty, Israel will need to prioritize attention to the internal crisis; adjust itself to the competition between the great powers, which is affected by the pandemic; adapt to the Biden administration and coordinate with it on Iran and other issues; expand alliances and normalization agreements with additional countries in the region; and be ready for military escalation in the north and in the Gaza Strip arena, which could occur even though all of the actors involved prefer to avoid it.

Strategic Survey for Israel 2020-2021 summarizes a year unusual in the nature of its complexity, shaped primarily by the COVID-19 crisis and the end of Donald Trump’s term as United States president. These two factors weakened the powers hostile to Israel and led them to focus on domestic affairs; concern about possible responses by President Trump in an election year and hope for the end of his presidency thus reduced the risk of a large-scale conflict in the Middle East. Consequently, Israel enjoyed relative calm on its borders over the course of 2020; operated in pinpoint operations in several arenas, in a way that thus far has not led to escalation; and took advantage of the singular characteristics of this period to advance normalization with a number of countries in the Middle East. This latter development both reflects and underscores a decline in the centrality of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on the regional and international agenda.

Some of these developments, which clearly have a positive impact on Israel’s national security, will continue in 2021. However, at the same time, Israel is grappling with a multidimensional crisis that threatens its economic and political stability, societal cohesion, liberal democratic values, and fabric of civilian life. This crisis did not begin with COVID-19, but the pandemic deepened existing economic, social, and governmental weaknesses and created new infirmities. While there is disagreement in Israel regarding the intensity of the crisis, it is clear that it has implications for national security, and highlights the need to adopt a broader framework in any discussion of national security issues. More specifically, at issue is not only the important connection between the domestic situation and Israel’s resilience in coping with external security threats, but also the underlying weakening of state mechanisms and the institutions essential to the state’s ongoing performance. Moreover, while the threat of an all-out military conflict has declined, the possibility of unwanted escalation exists, given unwanted dynamics of action and reaction.

The first months of 2021 will likely be dominated by the complex effort to vaccinate the Israeli population and people throughout the world against COVID-19, with the hope of eradicating the pandemic; the formation of a new administration in the United States headed by Joe Biden and the shaping of his domestic and foreign policy; the ongoing political crisis in Israel; and the possibility of a a response by Iran to the killing of the head of its nuclear program, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, and to additional operations carried out within its territory. Any assessment of the coming year, therefore, is subject to significant uncertainty. However, at the base of the assessment lies the assumption that 2021 – in the world, in the Middle East, and in Israel – like the preceding year, will unfold “in the presence of COVID-19.” The pandemic will not be eradicated all at once, but rather will be characterized by a gradual decline that could be accompanied by sporadic outbreaks and numerous mutations.

The International System: Recovery from COVID-19 amidst Great Power Competition

The COVID-19 crisis began at the end of a decade characterized by increasing strategic competition between the great powers, globalization that blurred physical boundaries, and an information revolution that changed the world order. The pandemic exposed existing trends, created new ones, and required all of the actors to respond in ways that fundamentally disrupted routine conduct throughout the world. During the first year of COVID-19, the international system continued to be polarized and divided, and central actors focused on their domestic affairs and on managing their respective economic and social crises – each in its own way. The economic crisis has been characterized by considerable differentiation – it has affected the West more than the East, and has impacted differently on various sectors: the tourism, aviation, and energy industries have suffered steep declines, while the technology sector has become a haven for investors and driven indexes up.

The year 2021 will presumably be characterized by the beginning of the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis and its myriad consequences, but the world will continue to operate in the presence of the pandemic, while the competition between the great powers will continue to be a central shaping influence. In the United States, the Biden administration will settle in and formulate its policy, first and foremost on domestic affairs (“healing America”), but also on the question of resumed United States leadership of the world’s liberal democratic camp, following the past few years marked by its absence from this traditional role. It will likewise need to position its stance with respect to the Middle East. China proceeds to recover from the crisis ahead of other actors, continues its fast growth, and will likely exploit its advantages in the current circumstances to heighten its influence. Russia will remain preoccupied with its domestic difficulties and with its faltering international standing, while exploiting its capabilities in the realms of cyber, intelligence, and cognitive warfare, and will perhaps have closer relations with China; Europe, which is in the throes of a political and ideological crisis, will try to renew the transatlantic alliance. The Middle East is unlikely to be at the forefront of the global agenda, except for the issue of Iran’s nuclear program, or if a significant military conflict erupts in the region.

Will work to “heal America” and engage in the question of the international order. US President Joe Biden

Photo: Adam Schultz/Biden for President (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The global center of gravity will therefore continue and perhaps even accelerate its eastward momentum. Nation states will gain strength due to the relative effectiveness that most have demonstrated vis-à-vis the pandemic, but will be challenged internally and externally. While the world will continue along some familiar tracks, in most of 2021 it will be less free – it is likely that at least some of the emergency measures and the invasive surveillance measures will continue; it will be less prosperous – there will be more unemployed people and more poor people; and it will be less global – we will fly less, work from home more, and crowd together less in cities. Countries will ensure the maintenance and expansion of strategic reserves and the independence of essential industries.

Overall, an accelerated adaptation to the new digital economy is apparent throughout the world, and technology-based economy has enabled countries’ functional continuity. Technology has been a central axis in research of the pandemic, development of the vaccine, and improved capabilities that continue to provide services – despite social distancing. Over the last few years the tech giants have become central actors in national security, have undermined the sovereignty of states, and have created, in effect, their own sovereignty in the digital realm. This development reached new heights in 2020, and became the target of countermeasures in various places around the world that aim to limit the power of the giants. Furthermore, there has been an increase in the range and scope of cyberattacks, both for strategic purposes of collecting information and disrupting systems, and for economic purposes; the level of cybernetic tension between countries has intensified; and the audacity of online criminal groups has increased, sometimes with the backing and direction of states. In turn, a more aggressive response by those attacked has also been apparent.

With the appointment of John Kerry as Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, the position has been upgraded and includes a seat in the United States National Security Council. This change illustrates both the importance that the Biden administration ascribes to the issue of climate change and the new administration’s approach that the issue is a clear matter of national security.

The coming year, therefore, requires that Israel adjust its policy to the competition underway between the great powers in the COVID-19 era. It must quickly adapt to the new administration in the United States and pursue a non-confrontational approach that recognizes American sensitivities and interests. Within this framework, Israel should engage in dialogue with the Biden administration in order to maximize shared interests and reduce risks (mainly on the issues of Iran and China, as well as on the Palestinian issue). The United States will remain Israel’s central and primary ally, but China’s current position in the international system requires that Israel continue to develop its relations with it, while in close coordination with the United States. Israel should also expand its expertise and knowledge base on China, and improve risk management. In addition, Israel should maintain its channels of dialogue and strategic coordination with Russia (given Moscow’s stabilizing role in Syria); and should try again to improve its relations with Europe, even though some of its stances on the Palestinian issue are opposed to Israel’s positions and interests. With respect to world Jewry, Israel should strengthen its relations with the Jewish communities, who are engrossed in their own crises, increase its support for them, and allow them a place in the discourse on Israel.

The Israeli System: The Challenge of an Ongoing Crisis to National Security Foundations

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, Israel is enmeshed in a multidimensional crisis – healthcare, economic, societal, and governmental – that has evolved for almost a year and coincides with the ongoing political crisis. This complex crisis could undermine the foundations of national security in the broad sense, as it leads to a weakening of the state’s mechanisms and institutions; this has been reflected in functional difficulties, paralysis of decision making processes, the loss of public trust in the government (which has plummeted over the past year) and other institutions, and the undermining of social solidarity. This state of affairs impacts on the stability and shared values that have characterized Israeli society and the fabric of civilian life.

Israel’s economy has been damaged primarily by the pandemic and by the way the crisis has been managed, but also by the impact of the crisis on the global economy. This harm is apparent mainly among the lower and lower middle class – small-business owners and people living below the poverty line.

The weakening of the state’s mechanisms (which is partly the result of a deliberate, systematic effort, and partly the result of other processes) is also reflected in the difficulty to effect orderly decision making processes and rely on regular decision making mechanisms. Beyond the increasing difficulty – in the post-truth and fake news era – of deciphering reality, understanding it, and making decisions, there is a noticeably low level of trust in Israel between the Prime Minister and the Minister of Defense and other ministers, who are denied information and responsibility and regularly excluded from decision making processes. This irregularity compounds the harm to the standing of institutional gatekeepers and content experts. The political crisis has led to paralysis of the government’s work, reflected most of all by the lack of a state budget and a multi-year plan for the IDF, and the proliferation of acting position holders holding central positions over extended periods of time. The need to curb the pandemic has also caused an unprecedented suspension of basic rights and freedoms in the framework of emergency legislation, some of it without parliamentary oversight.

The multidimensional crisis in Israel has led to weakened state institutions and a loss of public trust. Demonstration near the Prime Minister’s residence in Jerusalem

Photo: REUTERS/Ronen Zvulun

INSS researchers have debated the intensity of the internal crisis (in a historical perspective, and in comparison to the global crisis), and the scope of its impact on national security. While acknowledging the crisis, some maintain that Israel’s society and state mechanisms can cope adequately with it, as they did with severe crises in the past. According to this approach, the State of Israel has the proven ability to recover from crises; moreover, the sense of crisis mainly characterizes one side of the contemporary political map in Israel, and in effect the crisis in Israel is no different from similar crises that currently beset other Western liberal democracies.

The severe consequences of the pandemic will continue into 2021, even after the vaccine distribution. While the pandemic may gradually subside in the second half of 2021, its deep socioeconomic effects will accompany Israel into 2022 and subsequent years. A successful effort to recover from the crisis and bring about renewed growth will require Israel to undertake in-depth structural change. This demands stability in the political system to enable the formation of a broad national consensus. In order to start the process of emerging from the crisis, priority should be placed on professional and decentralized management of all dimensions of the crisis (health, economy, society). A new budget and economic program should be passed that prioritizes investing in civilian budget items and underprivileged groups, and there must be early and focused preparation for the growth stage following the pandemic. In the medium term, the government will need to lead a national effort of economic and social recovery, while creating closer relations between populations and reducing gaps. Furthermore, the COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated that Israel should implement a mechanism and modes of operation for coping with non-security crises.

The Regional System: A Decade since the Upheaval, and Expanding Normalization

The COVID-19 crisis is a kind of “aftershock” to the regional upheaval that undermined the region over the past decade. Even before the pandemic, the Middle East was characterized by instability, uncertainty, and volatility. There is broad agreement among observers and analysts that the region is mired in a deep crisis with historic implications and a turbulent struggle over its character. This struggle continues to unfold in two realms and along diverse fault lines: over the regional order, between different camps that are hostile to one another and struggling over ideas, power, influence, and survival; and within countries, between rulers and populations, surrounding fundamental economic and social problems and identity issues that have not been resolved and have even intensified in the past decade. The COVID-19 crisis deepens the fundamental economic problems – unemployment (particularly among young people), inequality, low productivity, governance lapses, corruption, and dependence on oil and external aid – and adds an even more acute dimension of uncertainty.

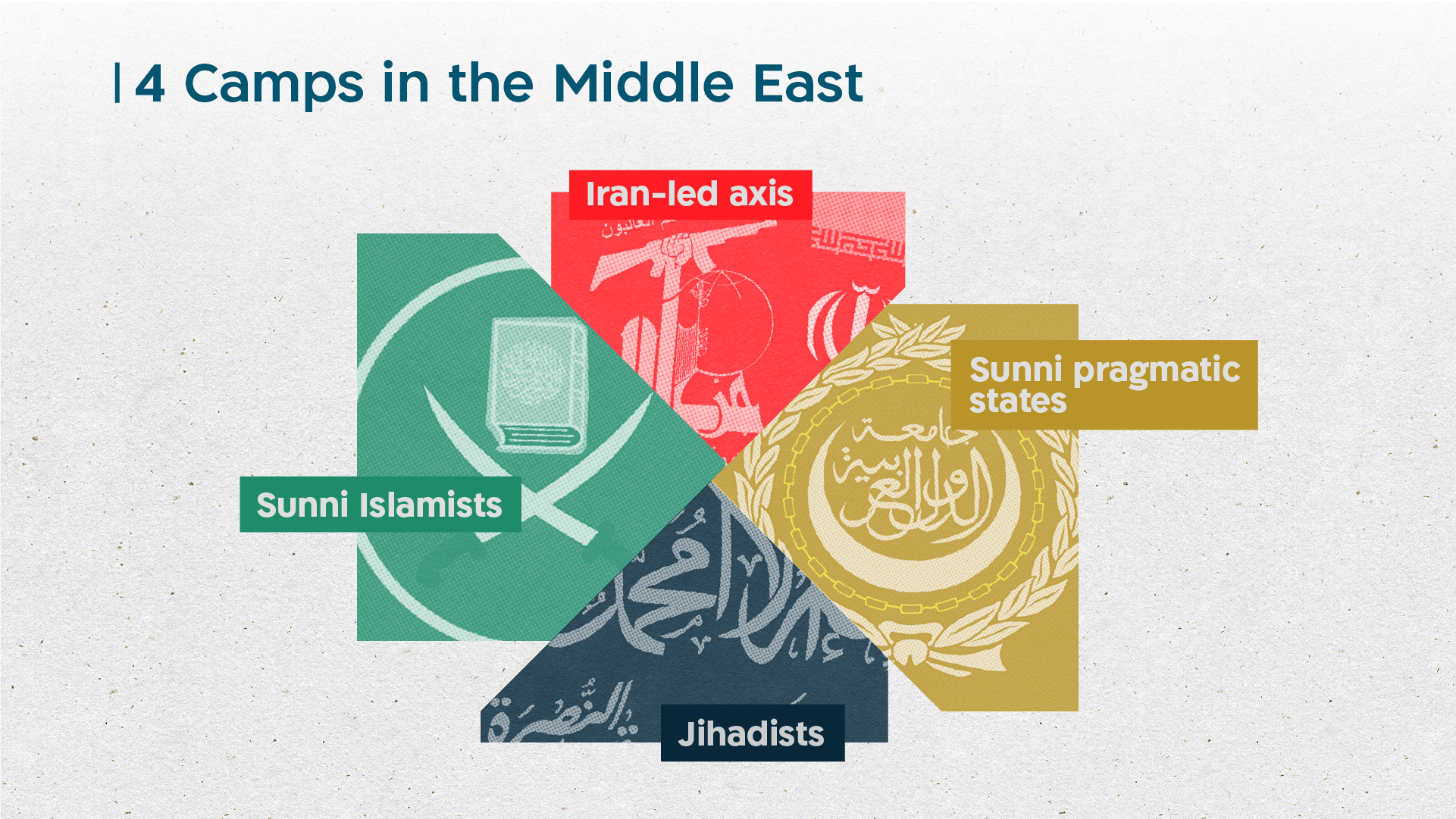

In 2020, against the backdrop of COVID-19 and the final year of the Trump presidency, several developments are noteworthy: the emergence of a series of normalization agreements between Israel and countries from the pragmatic Sunni axis; a decline in the confidence that had characterized the Iranian-Shiite axis in recent years, which is still united but absorbed in its internal problems; a rise in the assertiveness of the axis led by Turkey, which was reflected in the conflict in Libya and in the Mediterranean basin; and the recovery and reorganization efforts of jihadist factions. In early 2021, an end to the rift between the Gulf states and Qatar was announced.

The spread of COVID-19 forced all regimes to respond to the pandemic, and it seems that all have succeeded in addressing the challenge without significant damage to their systems of governance. Each regime has addressed the economic reality in its own way, but all of the solutions are short-term, and it is expected that the regimes will be hard-pressed to cope with the more underlying consequences (for example, the unemployment rates, which in many countries were high even before the crisis). 2019 was marked by large-scale popular protests that broke out in Sudan and Algeria (both of which consequently replaced veteran rulers) as well as in Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and even Iran. These protests were stopped with the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, and it is highly likely that they will be renewed subsequently (as is indeed the case in Lebanon and Iraq, for example) and pose challenges to the stability of the regimes. Even if the countries extricate themselves from the COVID-19 crisis in the coming year, it is possible that we will see a renewed wave of protests or additional destabilization.

In recent years Israel has consolidated its regional standing as a powerful ally of the pragmatic Sunni states. Against the backdrop of the states’ intensive focus on domestic problems and the strategic considerations that guide them, it became clear in 2020 that the impasse in the Israeli-Palestinian political process is no longer an obstacle to normalization with Israel. The agreements signed in 2020 between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Sudan, and Morocco’s announcement of its intention to establish full relations with Israel, stemmed mainly from the desire of these countries to advance political and security objectives with the assistance and sponsorship of the Trump administration, before the end of its term. Israel’s acceptance in the region by the pragmatic Sunni camp, and in this framework the (potential) strengthening of the front against Iran, is a positive process that bolsters Israel’s national security. However, Israel must take into consideration the partners’ limited practical contribution vis-à-vis Iran, certainly in the military sphere. In addition, this trend can also create challenges for Israel, for example if its new allies ask for its support and involvement in conflicts that they are involved in – but Israel is not.

Popular protests in the regional states are likely to be begin anew when the COVID-19 crisis is over.

Photo: REUTERS/Khaled Abdullah

In relation to the regional arena, therefore, Israel should work to expand the normalization trend to additional countries, while minimizing the risks to its qualitative military edge and without being drawn into non-essential conflicts. Israel should include Egypt, Jordan (while repairing relations with Amman), and the Palestinian Authority in Middle East partnerships. It is also possible that in the near future it will be appropriate to attempt to raise the level of relations with Turkey, even though the likelihood of success is not high.

Iran: At a Low Point, but Still the Primary Threat to Israel’s Security

Iran continues to pose the most severe threat to Israel’s security, both in its advancing nuclear program and its subversive regional activity. This threat defies the fact that Iran is at one of the lowest points that the regime has known, resulting from a combination of the extensive scope of the COVID-19 pandemic; the harsh economic situation stemming from the US sanctions that the Trump administration continued to impose throughout the year; the decline in oil prices; Iran’s failure to receive aid from international institutions; and the increasing lack of public trust in the regime, which was expressed in the demonstrations surrounding the accidental downing of the airplane in January 2020. The blows that the Iranian regime has suffered this year include the damage to the advanced centrifuge facility at Natanz and the killing of Qasem Soleimani early in the year and of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh at the end – the leaders of Iran’s regional strategy and its nuclear program, respectively. These challenges were joined by the normalization agreements between some Gulf states and Israel, which from Iran’s perspective represent a new and threatening axis in the Middle East.

These developments have led to the strengthening of the hardline elements in the political system, chief among them the Revolutionary Guards, which continue to deepen their involvement in the affairs of the state and economy while exploiting the government’s weakness. These moves and the efforts of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei (who is 81 years old) to ensure the rule of the hardliners before he departs the political scene will likely also figure in the Iranian presidential elections that are scheduled for June 2021.

Despite its difficult situation, Iran continues to try to advance its regional interests through its proxies, while building military, political, economic, and social infrastructure that will ensure its influence in the long term. Some of this infrastructure is aimed directly against Israel. However, the difficulties that Iran is facing in synchronizing and coordinating its arenas of influence – Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon – are increasing, while these countries also cope with their internal crises: in Syria, President Assad is hard pressed to regain his control throughout the country and renew state functions; in Lebanon the challenges facing Hezbollah have intensified, following the state’s internal collapse and the increasing domestic and international pressure on the organization; and in Iraq the potential for change in the internal balance of power has emerged, in a direction that could challenge Iran’s grip there.

Meanwhile, Iran continues to advance its nuclear program while deviating from and violating the 2015 nuclear agreement (JCPOA). According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) report from September 2020, Iran has already stockpiled over 2.5 tons of uranium enriched to a level of 4.5 percent and threatened, by means of a law passed in the parliament, to enrich to a level of 20 percent. Indeed, on January 4, 2021, Iran announced that it had begun enrichment to this higher level, which will return it to the level of enrichment before the JCPOA. It now operates about a thousand centrifuges at the Fordow facility and has transferred the centrifuge facility that was damaged at Natanz to an underground location, in order to renew its progress in this field in a secure environment. The main significance of all of these measures is the shorter time necessary to break out to a military nuclear capability, if Iran decides to do so, and the protection of this capability against external attack.

Iran continues to pose the most severe threat to Israel’s security. Missile launched during an Iranian military exercise

Photo: WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS

The impact of the killing of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh on Iran’s nuclear program is not yet clear. In the nuclear realm, Iran has maneuvered for many years between what is permitted and forbidden, concealed and open, possible and impossible. Fakhrizadeh was supposed to preserve the “weapons program” after it was frozen in 2003 – to ensure that the knowledge was not erased, and that capabilities were maintained. As the leader of a compartmentalized shadow organization, his knowledge belonged to him alone, and he was probably the one who was meant to lead the combined effort in the case of an Iranian breakout or “crawl” to nuclear weapons. Consequently, it seems that his killing constitutes a harsh blow to Iran and the nuclear program. On the other hand, his overall work over the course of many years was not crowned with success. Therefore there is concern that a talented replacement could be more successful at repelling the forces working against the Iranian program.

Biden’s election is unquestionably a positive development for Iran, mainly due to Trump’s departure from the White House and Biden’s inclination to return to the nuclear deal. The Iranian political echelon has already begun to debate a return to the 2015 agreement and the changes that Iran will demand in order to renew it. Apparently from Iran’s perspective these conditions include: completely removing the sanctions imposed by the Trump administration; adopting the agreement in its entirety, without change; and receiving compensation for the damages caused to it over the past few years. Both the United States and Iran are deliberating the question of the timing for renewing the negotiations, specifically, whether they should be revived before the elections in Iran in June 2021.

The inability to cope with Israeli attacks on Iranian targets in Syria has led Iran to turn to the cyber arena – attempts to attack the water network in Israel as well as the banking system and other Israeli civilian organizations. These attacks point to the Israeli civilian sector as a vulnerable realm, and signal a threat that must be addressed.

Israel should continue to see the completion of Iran’s military nuclear program as the main external threat to its security, and Iranian regional activity as a challenge that demands ongoing confrontation and response. In this context, Israel must formulate a policy vis-à-vis the Biden administration and the international community’s expected talks with Iran, and define Israel’s essential interests in relation to the renewal of the agreement or a new agreement. It is important that Israel carry out the dialogue discreetly and avoid a public confrontation with the administration, which would not serve its national security. At the same time, Israel should maintain a credible military option against Iran and plan to continue the “campaign between wars” against it, including against the growing threats from Yemen and in the Red Sea Theater.

The Northern Arena: Proactivity in Order to Weaken the Iranian-Shiite Axis

Likewise against the backdrop of the COVID-19 crisis are the challenges facing Israel in the northern arena. Chief among them is the activity of the radical Shiite axis, and in particular Iran’s entrenchment by means of its proxies in Syria and the establishment of Hezbollah military outposts on the Golan Heights, as part of the Iranian “war machine.” This entrenchment has lagged in relation to the Iranian vision and planning due to a series of factors, including the killing of Soleimani; Israel’s campaign between wars; the US “maximum pressure” policy; and the pressures of the COVID-19 crisis. Against this backdrop, the Iranian order of battle in Syria has been reduced and Iran continues to fortify its outposts through Hezbollah, Syrian army units under its direction, the recruitment of local Syrian elements for its militias, and internal security elements.

The reconstruction of Syria is an increasingly elusive goal, and it is estimated that many years and several hundred billion dollars are needed in order to rebuild the ruins. However, there is no one who will assume this burden. The grip of foreign elements in Syrian territory is increasing, and in addition to Russia and Iran, each of which for its own reasons is a partner in supporting President Assad, Turkey is also prepared for a prolonged stay in northern Syria and working to turn the areas under its control into territories under its military, economic, social, and cultural patronage. The United States maintains small military outposts in northeastern and southern Syria, but it is not clear how long it will continue to do so.

Lebanon is in the midst of an economic, political, governance, and healthcare crisis – among the most severe crises the country has known, with no solution on the horizon. The crisis also affects Hezbollah, but at present it seems that the organization is maintaining its standing and working to neutralize political and economic reforms that would undermine it. This, it appears, will block international aid to Lebanon, which is conditioned upon reforms. At the same time, Hezbollah continues, with Iran’s assistance, its military buildup, the precision missile project (the “precision project”), and capability to launch a ground operation in Israeli territory. Since the summer, Hezbollah has threatened to retaliate for the death of its operative in Syria in an IDF strike, but it has not been in a hurry to realize the threat. Meanwhile, negotiations over the maritime border between Lebanon and Israel have begun, but have reached an impasse.

Activity by the radical Shiite axis is the leading challenge to Israel in the northern arena.

Photo: REUTERS/Ali Hashisho

Israel operates in Syria – as part of the campaign between wars – against the entrenchment of Iran and Hezbollah, eroding and slowing it down, but it seems that it will not succeed in obstructing it entirely. On the other hand, the series of blows that Iran has suffered reduces its capacity for restraint and could lead it to respond against Israel, including by means of its proxies in the northern arena. In these circumstances, along with preparing for a possible Iranian response, Israel should continue its determination to take action against the buildup of the Iranian-Shiite axis, the Iranian entrenchment, and the precision project, while adapting the methods, arenas, and pace of action to the theater’s changing conditions. In particular, Israel should examine and define the right timing for action against the precision project, while understanding that this could lead to broad escalation. The presence of hundreds of precision missiles in the hands of the Iranian axis and in particular in the hands of Hezbollah, which could cause extensive civilian damage and paralyze essential infrastructures, is a strategic threat that must not be allowed to develop.

The challenges in the northern arena will not disappear, but will probably not reach the point of large-scale escalation soon, because at this stage all of the actors involved are focused on coping with the COVID-19 crisis and do not want war. However, in this period too, the risks of an unplanned and unwanted escalation dynamic are clear and could lead to war in the Lebanese, Syrian, and Iraqi theaters. This outline of a multi-arena war (the “northern war”) should be the main reference threat for war, and the Israeli government must prepare for it and ensure that the public is aware of its nature and possible costs, with an emphasis on severe harm to the civilian home front. At the same time, Israel should launch political and security efforts to prevent war and maximize other alternatives for advancing Israel’s objectives in the northern arena.

The Palestinian Arena: Preserving the Status Quo or Seeking Change?

In 2020 the Palestinian system sustained a series of blows. The Trump administration presented its plan for an Israeli-Palestinian agreement, which in effect ignored the Palestinians and their demands and adopted the position of the current Israeli government on many of the issues. The Palestinians proved unable to stop the intentions of the Israeli government to apply sovereignty to territories in the West Bank, and they lost veto power over the establishment of normalization between Israel and Arab states. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic created a public health crisis and deepened the economic and social crisis in the Palestinian arena. At the same time, Israel replaced the intended sovereignty program with a policy of creeping annexation and expanded construction in all the West Bank settlements. It seems that from the perspective of the current Israeli leadership, there is no interest in advancing a political process with the Palestinians, as in its view the current situation plays into Israel’s hands, certainly when the barrier of normalization with Arab states has been breached. Even if Israel ends up negotiating with the Palestinians (PLO/Palestinian Authority), it may try to demand that the Trump plan constitute the basis for discussion – a demand that is expected to be rejected by the Palestinians.

However, Biden’s election signals a positive turning point in the eyes of the Palestinian Authority leadership. The new administration is expected to display less support for Israel’s positions compared to the Trump administration, and it is also expected that the European countries, against the backdrop of renewed transatlantic closeness, will urge Biden to revive the political process and advance the two-state solution. The Democratic Party supports the two-state idea, but it is unlikely that the administration will cancel the recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital or return the embassy from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. In contrast, the incoming administration will likely cancel the recognition by the Trump administration of the legality of the Israeli settlements and settlement outposts in the West Bank. In addition, it is possible that it will open the PLO mission in the United States and maybe even an independent consulate in East Jerusalem.

The two Palestinian leaderships (the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Hamas in the Gaza Strip) tried, unsuccessfully, to reach accord on reconciliation, unity, and scheduled elections. The result was actually a deepening of the rift between the areas, with each side rigidly protecting its assets. In advance of Biden’s inauguration, there has been increased understanding in the Palestinian system of its dependence on Israeli assistance and the need to coordinate with Israel, which in turn has lent a certain level of legitimacy toward cooperation.

For the PA leadership, Biden’s election is a positive development. Mahmoud Abbas and Biden in Ramallah, 2016

Photo: REUTERS/Ali Hashisho

As for Hamas, the economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have forced the organization to try to formulate understandings with Israel in order to improve the humanitarian, health, and infrastructural situation in the Gaza Strip. Among its ranks, preparations have begun for elections for the leadership, which are expected to take place in the spring of 2021, and it seems that against this backdrop as well, the organization’s leadership will be deterred from provocations toward Israel, which could well lead to a military confrontation. Meanwhile, Hamas is expected to continue its military buildup, and especially to increase its stockpiles of rockets and unmanned aerial vehicles, which are intended for attacks within Israeli territory. On several occasions over the past two years rockets have been fired from Gaza – incidents that were explained as errors. It is possible that these were cases of intentional fire intended to signal to Israel that the military challenges are still in force, while risking the possibility of escalation. However, it is apparent that Hamas is not interested in escalation and has even succeeded in imposing the (relative) calm on other groups operating in Gaza.

Israel has an interest in maintaining a functioning, stable, and non-hostile Palestinian Authority. Therefore it should take a supportive and helpful approach that aims to strengthen it as the only legitimate address for a future agreement, and define the political objective of “transitional arrangements” that would shape a reality of separation (political, territorial, and demographic) and outline conditions for a future reality of two states (the INSS Plan). Regarding the Gaza Strip, the Israeli interest is a prolonged period of military quiet. Thus, Israel should designate Hamas as a temporary responsible party in the Gaza Strip and formulate a prolonged ceasefire with it, while seeking to block its additional military buildup, in return for improving the civilian conditions and infrastructure (electricity and water) in Gaza. In the case of a conflict, the IDF and the other security organizations must focus the IDF’s actions on inflicting severe damage on the Hamas and Islamic Jihad military wings.

The Operational Environment: Possible Escalation to an Unwanted War

Israel’s deterrence of large-scale conflict and war remains in effect. Its enemies are aware of its strength and all of them are preoccupied with internal problems, including the effects of the pandemic. A series of war games conducted by the Institute for National Security Studies in late 2019 and early 2020, before the COVID-19 crisis, led to the assessment that all of the actors in the northern arena wish to avoid escalation. The year 2020 confirmed that all of the significant powers in the arena are not interested in escalation. The experience of the past few years has shown that this is also the situation with respect to the power forces in the Gaza Strip.

In Israel, as in the ranks of Hamas and Hezbollah, awareness of the inherent risk in a potential escalation dynamic is joined by the conviction that a flare-up can be cut short after a few days of battle, similar to the short conflicts that took place in recent years in the Gaza arena. However, such a scenario could prove false, especially in the northern arena, if there are deaths on one side or both. In that case it is possible that response and counter-response would escalate, and lead to large-scale conflict and even to a war that the two sides do not want. Such a war could involve the Iranian-Shiite axis that includes Hezbollah in Lebanon, Iranian proxies in Syria and Iraq, and perhaps even Iran itself. Furthermore, the escalation could spill over into additional arenas, in particular to the Gaza Strip.

In such a war, the IDF would employ its offensive capabilities – on the ground, in the air, and at sea – and inflict extensive damage on its adversaries, but would have difficulty reaching a situation of clear, unequivocal victory. In such a war Israel would face massive surface-to-surface missile fire on the home front, some of which would be precision missiles and some of which would even penetrate the air defense systems; attacks on the home front by unmanned aerial vehicles and drones; the infiltration of ground forces into Israeli territory on the level of thousands of fighters; and cyber and cognitive warfare designed to undermine the stamina of the Israeli public and its faith in the political and military leadership. The IDF’s offensive components would face sophisticated air and sea defense systems and complex ground defense systems, including the use of the underground medium and advanced anti-tank missiles.

Israel’s deterrence against a large-scale conflict is strong, but a dynamic of escalation is possible. An Israel Air Force F-15 aircraft

Photo: IDF Spokesperson’s Unit

A multi-year plan for the IDF should be finalized and budgeted, adapted to the budgetary limitations and economic constraints caused by the COVID-19 crisis. Procurement as part of the US aid should be completed, and the IDF and the defense forces should be distanced from the political struggle in Israel.

The Structure of the Strategic Survey

The following chapters of Strategic Survey for Israel 2020-2021 summarize the assessments of researchers at the Institute for National Security Studies regarding Israel’s situation at the end of 2020 and its national security challenges for the incoming year. They discuss the international system, the Israeli system, the regional system, Iran, the northern arena, the Palestinian arena and the operational environment. This year the assessment also includes key points from the National Security Index, which is an ongoing, long term project at INSS to examine trends in public opinion in Israel in relation to national security issues; and a survey conducted among INSS researchers regarding a scale of threats and opportunities. In addition, the Survey includes short sections on issues related to national security: the impact of technology (with an emphasis on artificial intelligence); the post-truth and fake news phenomena; the cyber dimension; and climate change. Another short section analyzes several scenarios for the way the world and the Middle East will look in the post-COVID-19 crisis era.

The concluding chapter was written by INSS Executive Director Maj. Gen. (ret.) Amos Yadlin, with recommendations for Israeli policy for 2021.