The Middle East Economies: The Pandemic and the Gaps between the Regional States

Haggay Etkes, Tomer Fadlon, and Esteban Klor

Trends

The COVID-19 crisis has deepened existing gaps between wealthy and developing countries · Alongside the crisis: a rise in unemployment, higher prices, and increased budget deficits – and in the developing countries, political crises

The Middle East Economies: The Pandemic and the Gaps between the Regional States

Haggay Etkes, Tomer Fadlon, and Esteban Klor

Recommendations

Expand economic relations, using Israel’s economic power for regional influence · Strengthen the Abraham Accords · Pursue economic initiatives for development in the West Bank and Jordan, and in Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria, to reduce Iran’s influence

The economies of the Middle East are divided into high-income economies – those of Israel and the Gulf states – and poor/developing economies, with some states – Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen – suffering deep economic and political crises. The wealthy economies responded to the COVID-19 crisis with vaccinations for the majority of their populations and fiscal expansions, and global price increases are expected to lead to a moderate increase in inflation in these economies. The developing economies, however, have had difficulty vaccinating their populations and expanding their budgets, and some – including Iran, Lebanon, and Turkey – are also suffering from high inflation. Given the Middle East economic reality and Israel’s relative economic strength, there is great importance for Israel to develop a comprehensive strategy and policy as part of the soft power at its disposal and utilize it to deepen its regional influence (alongside the use of hard/security power). There are many opportunities at hand, first and foremost the Abraham Accords, which could strengthen economic relations in the Gulf, and Turkey’s increasing economic difficulties, which could make Ankara more interested in deepening connections with Israel. At the same time, it is essential to examine direct and indirect initiatives for improving the economic situation in Gaza (a humanitarian time bomb), the West Bank, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon, which is collapsing, including utilizing international and regional aid programs to limit the influence of Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon.

The Middle East Economies: Statistical Appendix

Economic Clubs

Viewed through the economic prism, the Middle East is characterized by differences between groups of countries in terms of how they have coped economically with the crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, and in terms of economic forecasts for the next few years, when the world will move to a more steady routine of living with COVID-19.

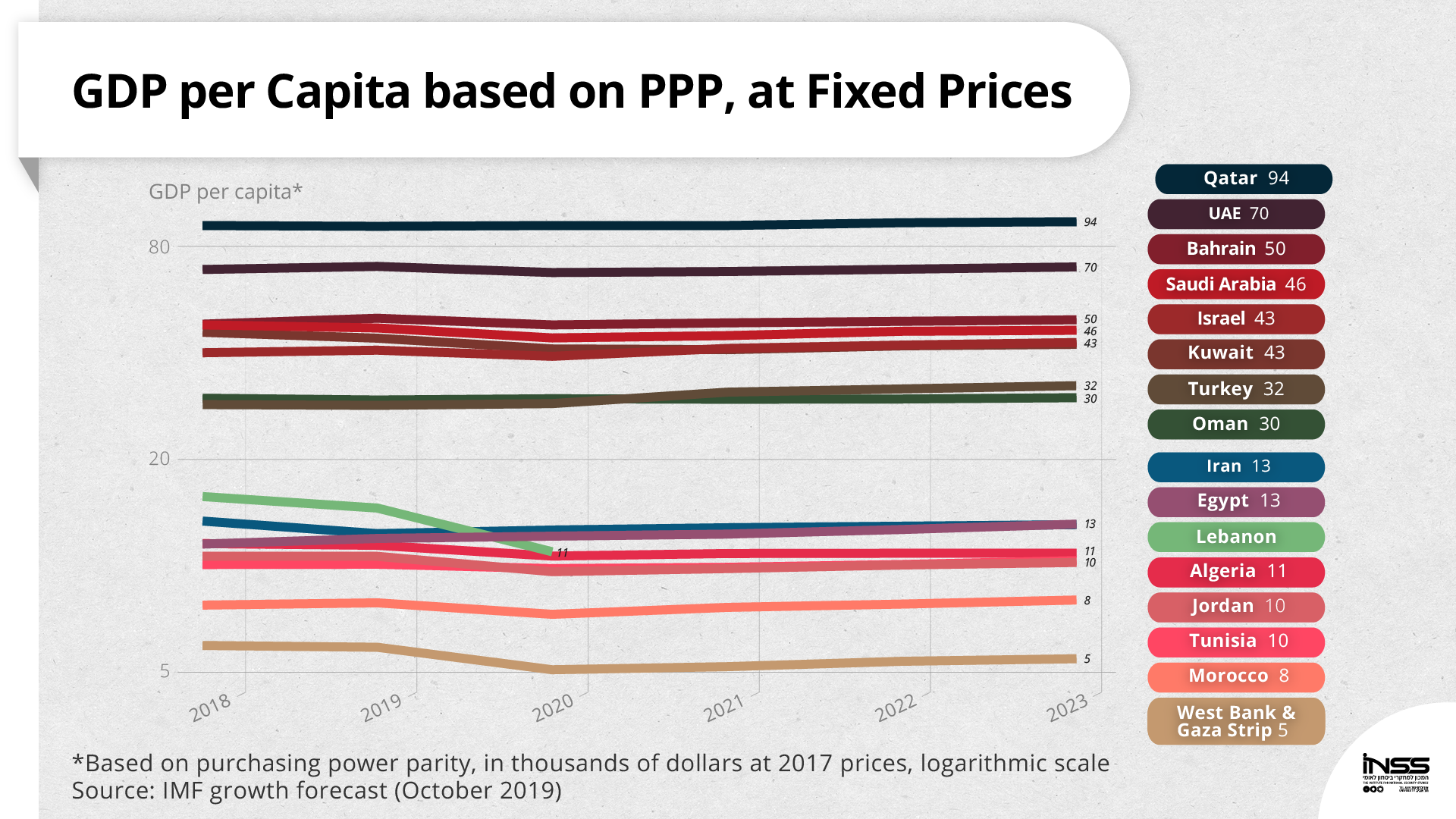

The central characteristic of the regional economy is the divide between the club of economies with high incomes (GDP per capita above $40,000, based on purchasing power parity), which includes Israel and the Gulf states, and a club of developing economies with low-medium income (less than $15,000, per capita based on purchasing power parity), which includes the oil importers – Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. A significant portion of the developing countries suffer from political instability, which in the cases of Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen is manifested in the collapse of the state. Turkey is an intermediate case of an economy with medium income ($32,000) that is expected to continue to grow in the next few years despite an unusual monetary policy that leads to high inflation and devaluation of the local currency (Figure 1 and Table 1 in the online appendix).

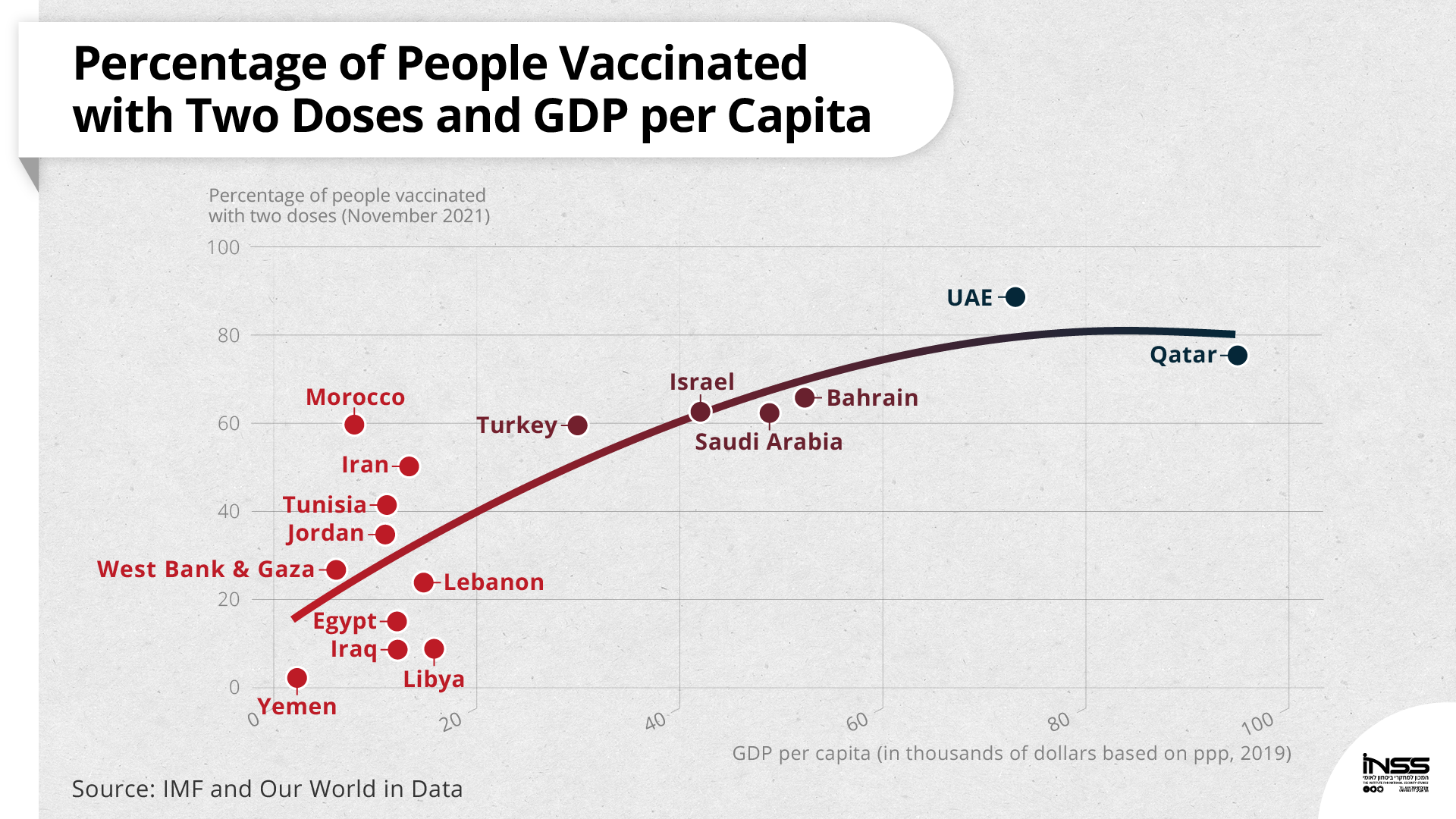

The COVID-19 Pandemic

The differential impact of the pandemic on the region’s countries is reflected in the supply of vaccinations to the respective populations: the wealthy countries succeeded in vaccinating over 60 percent of their populations with two doses by November 2021. In contrast, the rate of vaccination in the medium-low income countries ranges from about 50-60 percent in Turkey, Morocco, and Iran, to countries that have vaccinated less than a fifth of their populations – Egypt, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen. There are indications that mortality from COVID-19 also varies across the economic clubs: by the end of 2021 the excess mortality and the reported mortality during the pandemic in Israel, Oman, and Qatar were less than 100 per 100,000 people, while in the developing economies such as Iran, Lebanon, and Egypt, excess mortality was more than 200 per 100,000 people. These disparities probably reflect the difference between the wealthy and vaccinated countries, with low mortality from COVID-19, and the developing countries, which have suffered high excess mortality (Figure 2 and Table 3 in the online appendix).

Inflation and Monetary Policy

The inflation rate in the region’s countries is expected to rise in 2021-2022 relative to the levels that existed before the COVID-19 pandemic, as a result of the rise in food and energy prices. Increases in global demand for products and supply chain problems related to the global recovery from the pandemic will increase the inflationary pressures. These pressures will be especially high in countries with low/medium incomes that do not export oil. In some of these countries, the price increases will be accompanied by significant devaluation of the local currency. For example, in Lebanon there is three-digit annual inflation approaching 200 percent, along with a collapse in the value of the Lebanese pound. In Turkey, the inflation rate rose to over 20 percent with an almost 50 percent devaluation of the Turkish lira in 2021. High inflation rates will cause a decline in the real income of the lower strata. Higher increases in local and global food prices could lead to food insecurity for a significant portion of the population and perhaps also political instability (such as the situation in Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon). In addition, these processes could place a burden on the budgets of countries that subsidize essential goods.

The monetary situation in the wealthy oil-exporting countries and in Israel is expected to remain stable. They will enjoy relatively low inflation rates (under 3 percent), stability in the value of their currencies (in most of these countries the local currency is pegged to the dollar), and a rise in revenues as a result of the rise in oil prices.

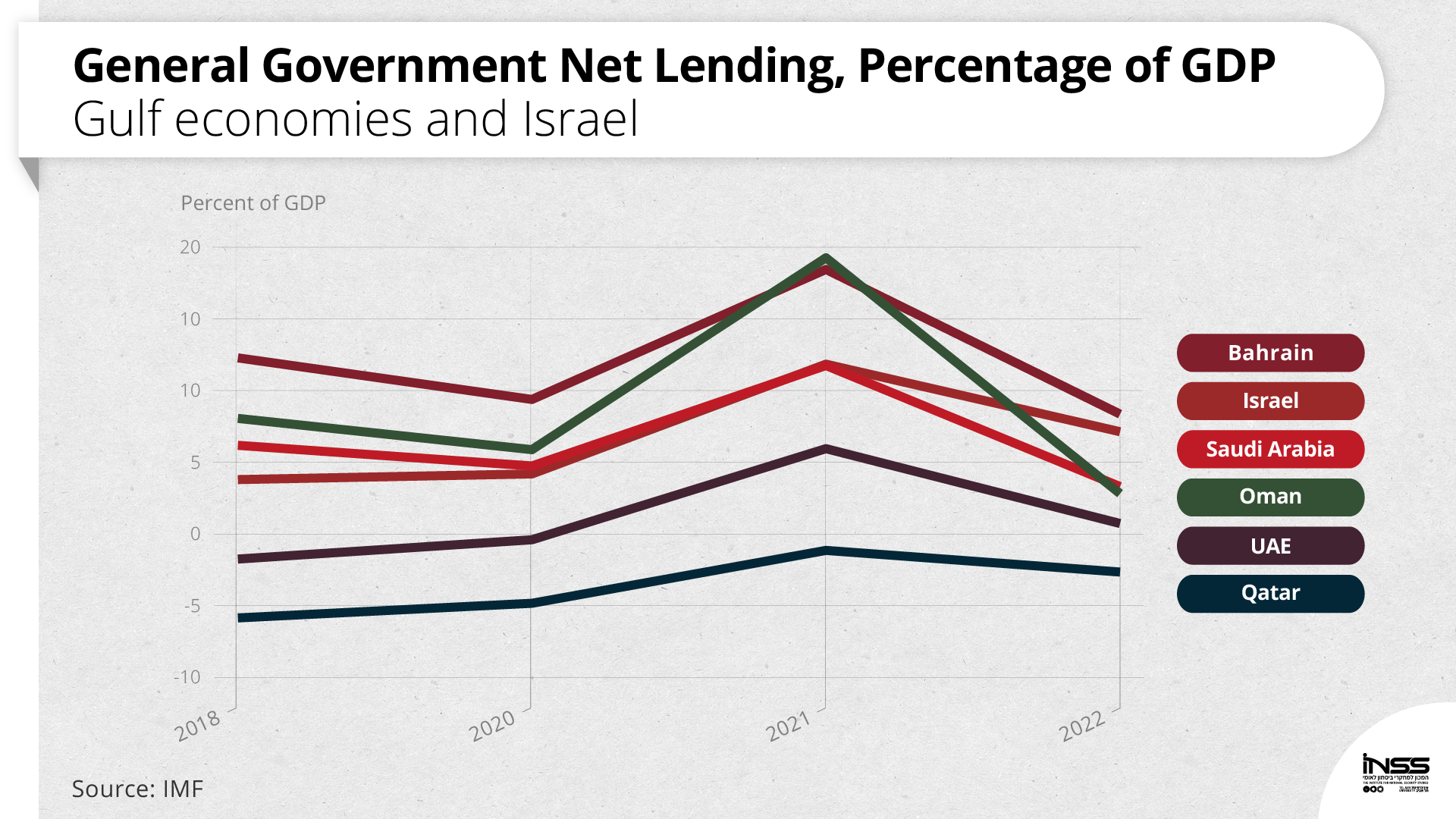

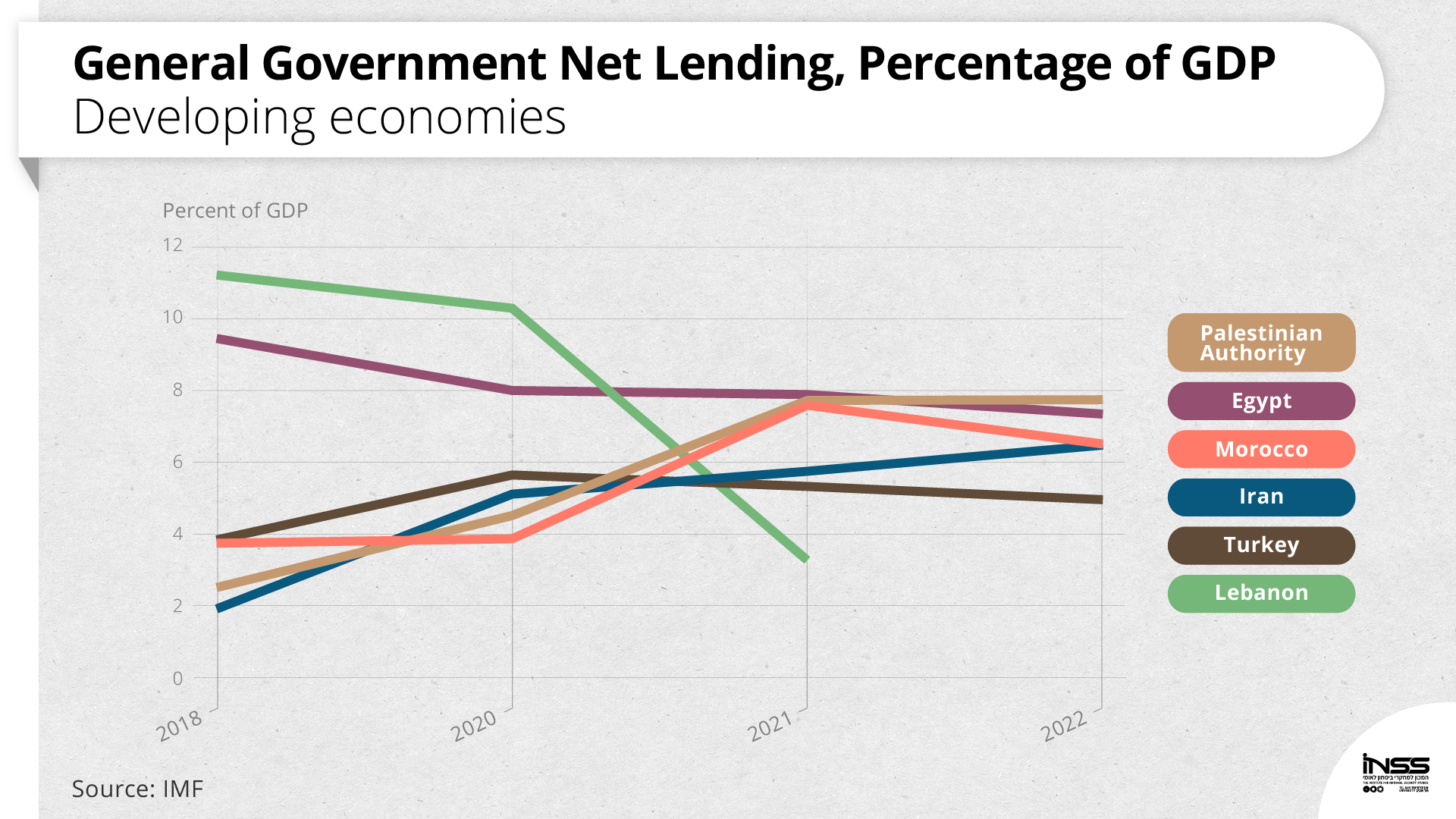

Fiscal Policy

The fiscal policies of the wealthy countries were counter-cyclical: the deficit grew in 2020 and is expected to shrink in 2021, and as such, the budget supports the stabilization of growth, consumption, and employment in these economies during the crisis. The counter-cyclical policy in the Gulf countries also stemmed from a decline in oil prices that affected their revenues. In contrast, the budgets of most of the developing countries in the region were non-cyclical and did not support growth and employment during the cycle. The exception was Lebanon, which experienced fiscal contraction in 2020 both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP (Figures 3a and 3b and Table 4 in the online appendix).

The fiscal distress led several countries in the region to sell SDR (Special Drawing Rights) reserves, with allotments expanded by the International Monetary Fund during the COVID-19 crisis: Lebanon sold reserves amounting to about 6 percent of GDP (about $870 million), Iraq amounting to 1.1 percent of GDP ($2.1 billion), and Jordan amounting to 0.5 percent of GDP (about $460 million). As of October 2021, Iran, Syria, and Venezuela (which are subject to currency crises) had not yet sold their reserves, apparently due to American sanctions imposed on them.

The expansionary fiscal policy on the one hand and the growth slowdown due to COVID-19 on the other hand in the vast majority of the region’s countries led to increases in debt-to-GDP ratios, which are expected to remain at high levels in the coming years (Table 6 in the online appendix). The expected rise in interest rates in the West with the renewal of inflation is expected to increase the debt-service burden of the majority of the countries in the region and in particular the poor/developing countries.

The External Sector, Tourism, and Transfers

The wealthy oil-exporting countries experienced increased deficits in current accounts (exports minus imports including tourism services, labor, and more). Israel, however, enjoyed an increased surplus in its current account due to growth in hi-tech exports and the decline in imports as a result of lower prices of fuel and goods and also of a drop in Israeli tourism abroad. In contrast, the majority of the poor/developing countries did not experience a worsening of their current account deficits, in part due to lower prices of oil and goods in 2020 and the stability of remittances transferred by their citizens working abroad, and despite the decline in tourism.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the export of tourism services declined dramatically in the region, similar to global tourism trends. In the past few years, some countries of the Middle East, both wealthy and poor, have developed the tourism industry as an important source of income. Wealthy countries, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, hoped that the investment in tourism would diversify the local economy. In poor countries, especially Jordan and Lebanon, the tourism industry contributed about 15 percent of GDP before the crisis and was a central source of foreign currency. In 2020 the MENA countries experienced a 70 percent drop in the number of incoming tourists. According to the World Tourism Council, tourism to the region is expected to increase by only 27 percent in 2021. This is a relatively low percentage that is explained in part by the low vaccination rate. In the absence of new COVID-19 variants and in the most optimistic scenario, the countries of the region will only return to the numbers prior to the crisis in 2025. The sharp decline in the number of incoming tourists is accompanied by the ongoing decline in direct foreign investment in the region since the 2008 financial crisis and the Arab Spring.

As a result of these processes, there is increased importance of remittances from family members abroad as a significant source of income for developing countries in the region. With the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a decline in these transfers, although to a lesser extent than in early forecasts. This is the result of the economic recovery of the wealthy countries from which the workers transfer their money. For example, the Gulf oil-exporting economies are the source of a quarter of all transfers from family members in the world. The rise in the price of oil in 2021 improved the employment status of these workers, who transferred money to the developing countries – including in the Middle East region. This income source emphasizes the gaps between the countries in the Middle East: foreign workers send money from wealthy countries to poor countries that are in need of these transfers (Figure 4).

3-digit inflation and the collapse of the pound. Cartoon protesting the rising gasoline prices in Lebanon

Growth and Employment

The growth patterns of the region’s economies during the COVID-19 crisis maintained the gaps between the developed economies and the poor/developing economies, and in certain cases, such as Lebanon, even expanded them. Over the last two years, the majority of the region’s countries experienced a decline in GDP due to the outbreak of the pandemic, and enjoyed only a partial recovery in 2021. They are expected to converge to a lower growth trajectory in comparison to the trajectory that was anticipated prior to the pandemic’s outbreak. The negative growth in 2020 stemmed from the suspension of economic activity due to the pandemic, and the Gulf countries also suffered from lower oil prices. The positive exceptions are Israel, which partly closed the GDP gaps with the Gulf countries, and two developing countries, Turkey and Egypt. The negative exceptions are the economies of Lebanon, which is suffering from a collapse and a failure of the state’s institutions, and Iran, which is slowly recovering from the impact of the sanctions imposed on it and from the COVID-19 pandemic but has not yet returned to the GDP per capita that it had in 2017. The lack of data on Syria, whose economy has been severely damaged in the past decade, makes it difficult to analyze the impact of the crisis there.

Similar to growth, the employment rate (above age 15) in most of the countries about which there is public information shrank after the outbreak of the pandemic in the second quarter of 2020 and recovered after a few months (Egypt and the West Bank) or gradually over the course of a year and a half (Israel, Turkey, Morocco, and foreign workers in Saudi Arabia). Employment in the Gaza Strip has not yet recovered from the decline following the outbreak of COVID-19, and employment in Jordan, which has suffered ongoing decline in recent years, has reached a very low level. In contrast, the employment of Saudi citizens has continued to rise during the last few years, and was not affected by the outbreak of COVID-19.

The Digital Economy in the Middle East

One of the factors contributing to the widening gap between wealthy and developing countries in the region during the COVID-19 crisis is the digital gap. Digital infrastructure enables economies to function even when restrictions are imposed on the movement of residents, and enables students to continue to learn remotely. According to a UNICEF report, only half of students in the Middle East had access to remote learning during the crisis. The region’s countries are now trying to overcome the gaps that have developed in the past decade through investments and digitization processes. According to studies published in the past year, even for countries that did invest in digitization (such as the United Arab Emirates), gaps still remained, and they are ranked very low when it comes to cyber security. According to these studies, the rest of the countries among low-income economies are also ranked very low in other digital categories.

Slow recovery from the sanctions and the pandemic. Street in Iran, 2021

Photo: Majid Asgaripour/WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS

Policy Recommendations

Developing economic relations with economies in the Middle East could strengthen the importance of relations with Israel for the region’s wealthy and developing countries. Cooperation in fields related to water, healthcare, and desert agriculture technologies is relevant for most countries in the region. Wealthy countries could attach special importance to cooperation in the field of cyber security, while developing economies could attach special importance to cooperation in the fields of energy and employment. That said, maintaining and expanding employment in Israel of workers from the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Jordan could adversely affect employment of Israelis. This is a particular concern for Israel’s Arab sector, which has suffered a sharp decline in employment in recent years. Military exports to countries in the region could also strengthen Israel’s importance to the purchasing countries.

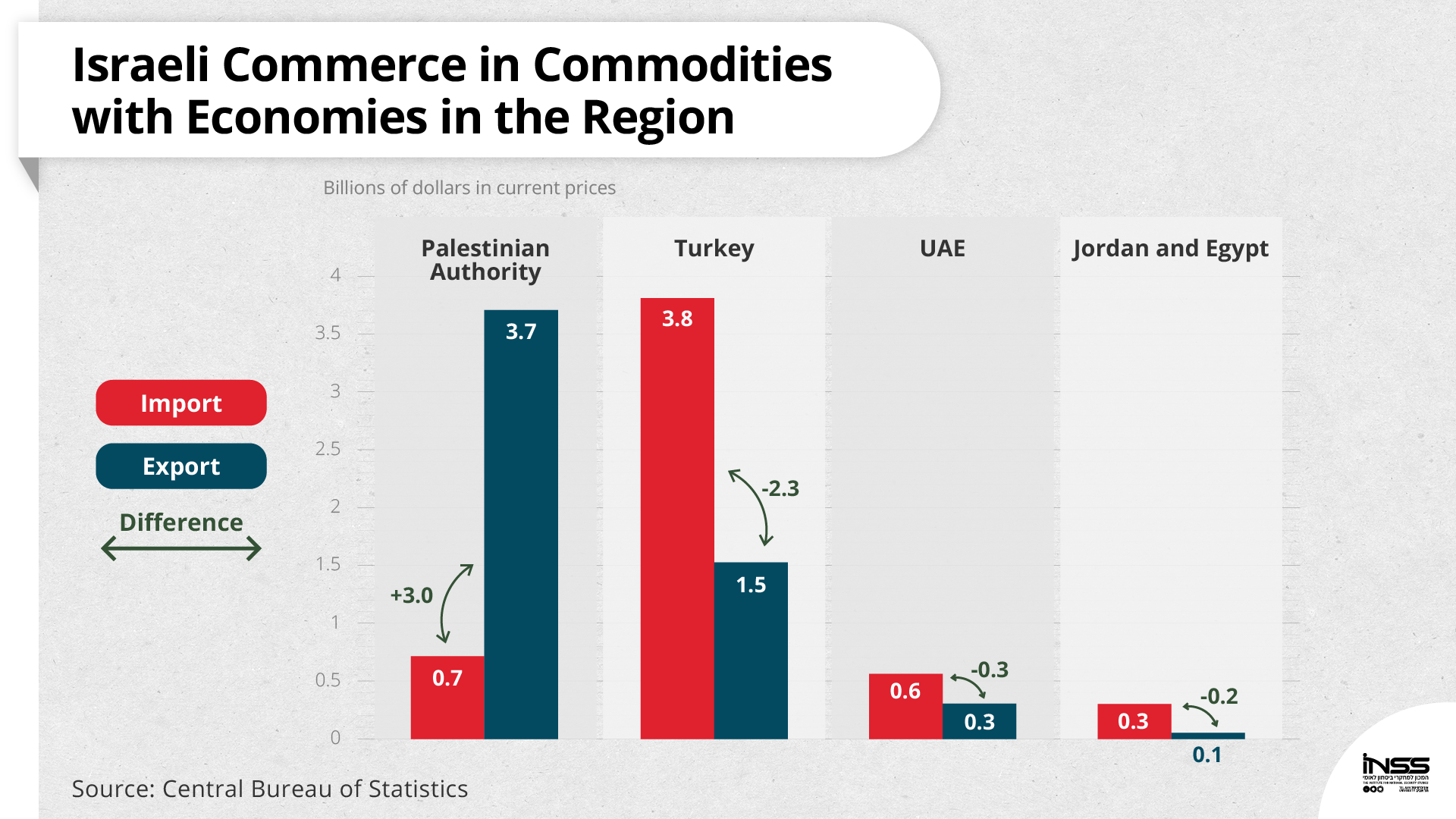

Growth and employment in the Israeli economy can be promoted primarily through relations with the region’s wealthy countries and with Turkey. Israeli trade with economies in the region still focuses on trade with Turkey and the Palestinian Authority, and trade with the United Arab Emirates reached about $1 billion within a year of signing the Abraham Accords. Trade with the rest of the region’s countries is limited (Figure 4). Promoting trade with the Gulf states could not only expand Israeli exports to them and through them, but also lead to real growth in Israel by lowering the cost of living, by importing from the East through the UAE. In addition, expanding the financial integration between Israel and the Gulf countries would partially protect these economies from the impacts of oil price volatility.

The COVID-19 pandemic also illustrates the diplomatic importance of the international financial institutions. For example, the allocation of SDR by the International Monetary Fund helped Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq, but not countries under American sanctions such as Iran, Syria, and Venezuela. Similarly, the international institutions are helping the developing economies, such as Jordan and Egypt, whose stability is an Israeli interest. The continued American influence on these institutions generally also serves Israeli interests.