Iran: At a Low Point, but Still the Primary Threat to Israel’s Security

Sima Shine and Raz Zimmt

Snapshot

Economic low and severe blows · Nonetheless, Iran advances nuclear program and regional entrenchment · Attempted cyberattacks on Israel · Demands to rescind the sanctions before any renewal of nuclear talks

Iran: At a Low Point, but Still the Primary Threat to Israel’s Security

Sima Shine and Raz Zimmt

Recommendations

Iran’s nuclear program remains the primary threat to Israel’s security · Retain credible military option · Coordinate with the US on renewed nuclear talks, and present Israel’s interests in a new agreement

The past year was among the hardest the Islamic Republic has known. Beginning with the killing of Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani and the downing of the Ukrainian airplane and the ensuing protests, it was marked by an increasingly severe economic situation, the COVID-19 pandemic, the normalization agreements between Israel and Arab states; and the killing of the head of the military nuclear program, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh. Biden’s election offers new hope of removing the sanctions and returning to the nuclear deal. Iran’s opening position states that the existing agreement is not open to negotiation, and returning to it is conditional upon the complete removal of all the sanctions. In the meantime, progress on the nuclear program continues, against the backdrop of threats to intensify the violations and reduce IAEA supervision. Israel should refrain from a public confrontation with the Biden administration, urge it not to yield the sanctions leverage at the outset, and ensure that Iran’s regional activity and missile program are addressed.

2020: A Challenge-Ridden Year

The past year was one of the most difficult experienced by Iran since the founding of the Islamic Republic. It began with the killing of Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani and the downing of a Ukrainian airliner and ensuing riots; and continued with the COVID-19 pandemic. According to official Iranian figures, more than 55,000 citizens have died in the pandemic, though the actual number is probably much higher. The pandemic exposed several weaknesses and failures by the regime, exacerbated Iran’s economic distress, and influenced internal processes in the political system, specifically the strengthening of hardline factions, headed by the Revolutionary Guards. Compounding these challenges were the normalization agreements between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, followed by agreements with Sudan and Morocco, and the killing of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, head of the Iranian nuclear program.

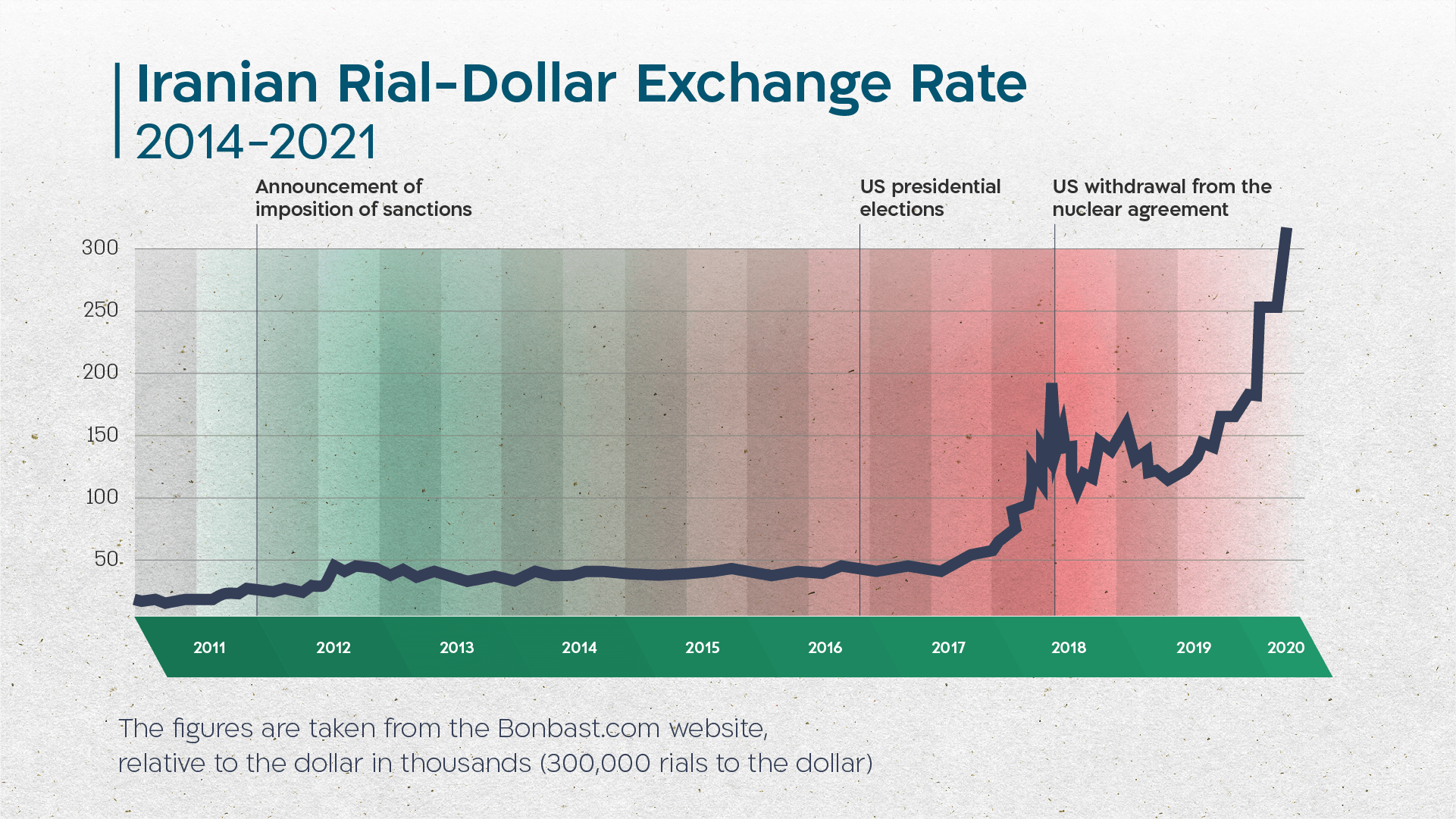

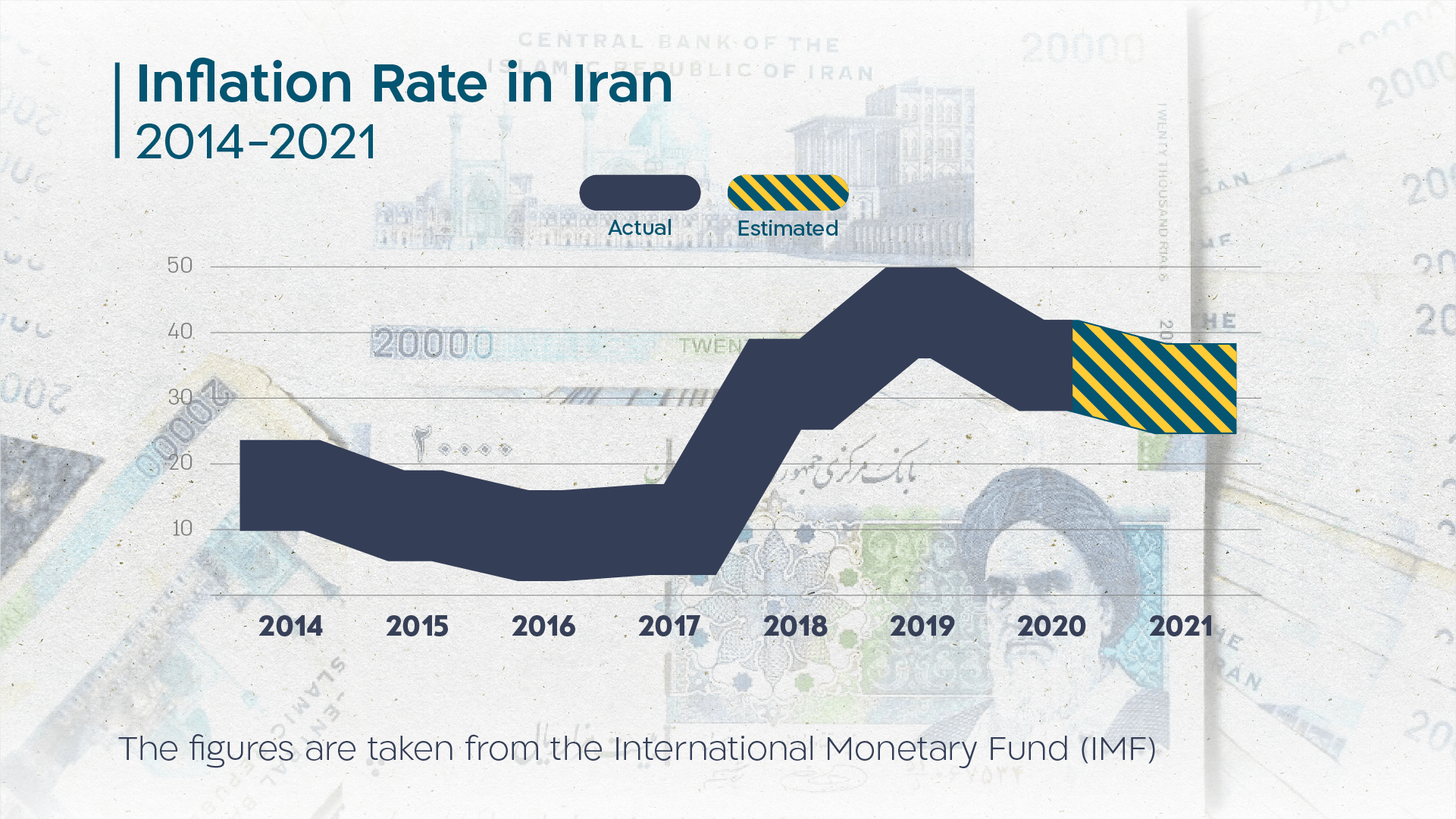

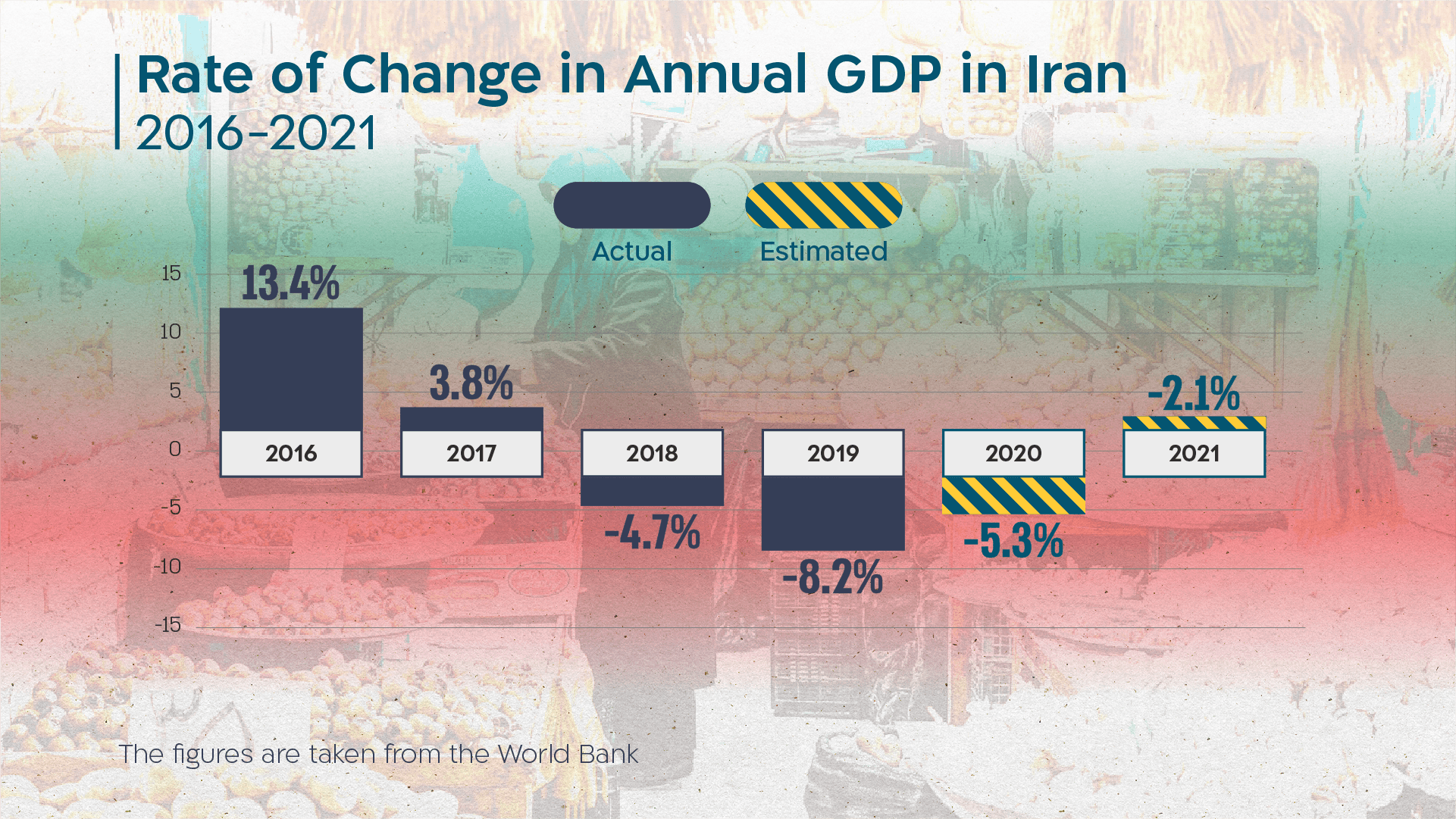

The economic realm: The COVID-19 pandemic coincided with tighter sanctions against Iran imposed by the United States and plunging oil prices. The pandemic’s effect was especially acute because it also struck sectors where sanctions had only a limited impact. The severe economic crisis features a high negative growth rate (-5 percent growth is expected in 2021), the collapse of the Iranian currency (the rial) against the US dollar, a severe budget deficit, inflation in excess of 40 percent, and reduction of the country’s foreign currency reserves.

The political realm: The hardliners in Iran, led by Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, continued to gain in strength. In the February 2020 elections, the conservatives regained absolute control of the Majlis (the Iranian parliament). In tandem, the COVID-19 crisis and the ongoing confrontation with the Trump administration have strengthened the status of the Revolutionary Guards, who continue to heighten their intervention in the management of state and economic affairs, while taking advantage of the government’s weakness. These factors and trends, including Khamenei’s efforts to ensure the hardliners’ control after he leaves the political scene, will also impact on the Iranian presidential elections, scheduled for June 2021.

The regional realm: Iran faces growing difficulties, among them continued internal unrest in both Iraq and Lebanon; the profound effects of the massive explosion at the Beirut port on the status of Hezbollah; and the sanctions imposed on Syria and Hezbollah by the US administration. Israel’s ongoing attacks in Syria also pose a significant challenge to the Iranian regime. The regime’s inability to devise an effective response has led Tehran to rely more heavily on cyber warfare, including attempts to attack the water system in Israel and efforts to attack the Israeli banking system and other Israeli civilian organizations. In addition, Iran’s rivalry with Russia and Turkey over influence in Syria continues. These disputes and difficulties, however, have not changed Iran’s long-term interest in Syria, which Tehran strives to deepen by consolidating its inroads in Syria’s security, economic, educational, and cultural-religious establishments. In Iraq as well, despite its considerable influence, Tehran is aware that Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi seeks to balance Iran’s influence against that of Washington and hopes to achieve closer ties with the Gulf states, Jordan, and Egypt. The normalization agreements between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, and in particular the future supply of F-35 aircraft to the UAE and the thawing of relations between Israel and Sudan, an ally of Iran in the more distant past, are alarming to Tehran.

The nuclear realm: Despite these internal and external difficulties, Iran has continued to advance its nuclear program in violation of most of the clauses in the nuclear agreement. According to a report published by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in September 2020, Iran possesses over 2.5 tons of uranium with a low level of enrichment, and its enrichment efforts continue at two sites. In addition, gas has been fed into advanced centrifuges, and a deep underground facility for assembling new centrifuges is under construction in place of the Natanz site that was sabotaged and severely damaged. The IAEA also does not accept Tehran’s explanations of its nuclear activity at sites that were not reported to the agency, in violation of Iran’s obligations under the NPT. Following the killing of Fakhrizadeh, the ensuing threats of a harsh response against the perpetrators, and Iran’s accusations against Israel of responsibility for the killing, a hostile message was sent to the incoming US administration: a law was passed by the Majlis demanding that the Iranian government raise the level of uranium enrichment to 20 percent, renew the activity of the research reactor in Arak, and cut back cooperation with the IAEA. The Iranian parliament demanded that these actions be taken within two to three months, unless all of the sanctions against Iran are removed. On January 4, 2021 Iran announced it resumed enrichment to 20 percent.

Accusing Israel and sending a threatening message to the Biden administration. The funeral of nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakrizadeh

Photo: Iranian Defense Ministry/ WANA (West Asia News Agency)/Handout via REUTERS

What Does 2021 Hold in Store?

Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential elections is unquestionably a positive development for Tehran, mainly because Donald Trump has left the White House and Biden has announced his willingness to return to the nuclear agreement. A heated debate is already underway in the Iranian political system about the resumption of negotiations with the United States. In principle, the pragmatic camp, led by Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, supports a renewal of the dialogue with Washington, in the hope that this will lead to the removal of sanctions and an improvement in the situation of the Iranian nation. The radical hardline camp, on the other hand, opposes any return to negotiations, claiming that the United States cannot be relied on, and that an effort should be made to solve Iran’s economic distress through a “resistance economy,” an approach adopted by Supreme Leader Khamenei. The dispute embodies political considerations that will be at the heart of the forthcoming presidential elections in Iran. Rouhani’s opponents have no wish to supply their rivals with a political achievement before the elections. Furthermore, various statements by Biden and his advisers have sharpened the concern in Iran that the new US administration does not intend to fully remove the economic sanctions merely in return for a return to the nuclear agreement, and intends to demand improvements to the agreement, which Tehran opposes.

In addition, Iran, which is aware of the anticipated changes in the new administration’s priorities, will have to contend with a geopolitical environment that differs in a number of respects from the one of recent years, headed by an expected improvement in transatlantic relations. President Biden attaches importance to a renewal of the alliance between the United States and Europe and NATO. Iran benefited from the tension between the Trump administration and the United States’ European allies, and adopted a policy designed to keep Europe on its side in its efforts to isolate the administration. This Iranian policy achieved considerable success, highlighted by the vote by European countries in the UN Security Council in October 2020 against extension of the arms embargo on Iran and their opposition to the US attempt to restore Security Council sanctions by exercising the snapback mechanism. In its relations with Russia and China, Iran must take into account those countries’ desire to avoid a confrontation with the United States at the outset of Biden’s term. There are possible new weapons transactions between the two countries and Iran on the agenda that have in any case been complicated by Iran’s difficult economic situation.

Iranian hardliners oppose a return to negotiations with the United States. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

Photo: SalamPix/ABACAPRESS.COM

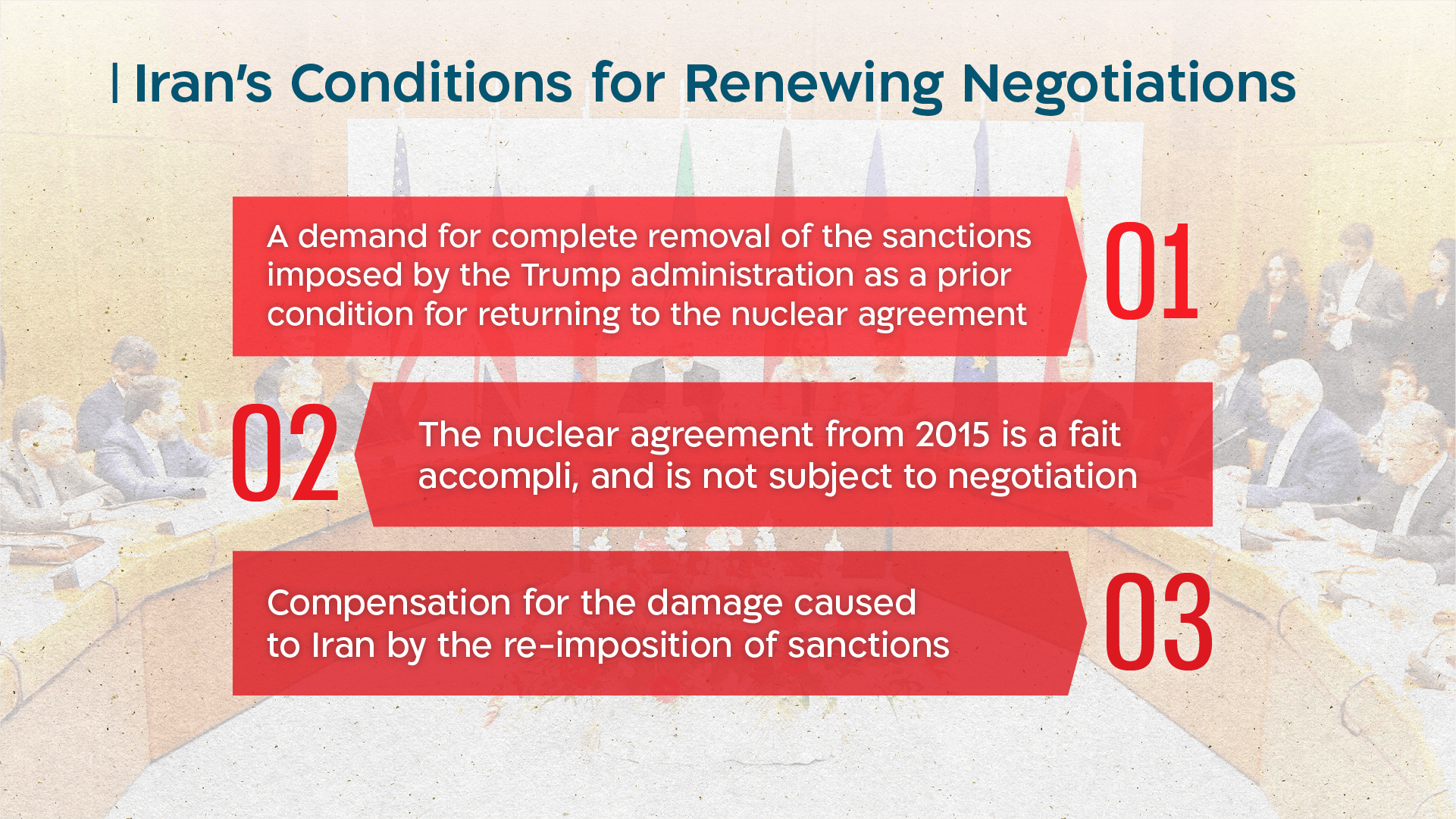

The various statements by Iranian leaders contain clear messages to the United States and European countries that define Iran’s conditions for a possible renewal of the negotiations. While clearly these are opening conditions that are likely to change in the face of a concrete proposal from Washington and pressure from European parties with a strong interest in renewal of the dialogue, Iran’s demands draw the following baseline: there must be an absolute removal of the sanctions imposed by the Trump administration, as a prior condition for returning to the nuclear agreement; the 2015 nuclear agreement must be seen as a fait accompli, and not subject to negotiation; and there must be compensation for the damage caused to Iran in recent years by the re-imposition of sanctions.

The complex landscape in early 2021 differs from the situation in the years 2013-2015, when negotiations took place between the P5+1 countries and Iran. Inter alia, a number of processes and dates are on today’s agenda, and some clash with each other. On the one hand, there is a clear desire among the Biden team to act quickly to revoke the measures taken by Trump on a number of matters, among them the Iranian issue. It is therefore likely that Biden’s advisers will try to take advantage of the period before Rouhani and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, a familiar interlocutor, leave office, in order to establish some kind of dialogue. European parties share this priority, and will likely formulate a proposal that they hope Tehran will approve. On the other hand, it is doubtful whether the Tehran leadership will be ready for such a major step before the Iranian elections, because the issue of a dialogue with the United States will certainly feature prominently in the election campaigns of all the candidates. Furthermore, the explicitly suspicious attitude of Supreme Leader Khamenei toward the United States has become even more extreme. There is no doubt that he is weighing his legacy, in which Iran’s resistance policy takes clear priority over any dialogue with the “Great Satan.”

In addition, the United States requires “time for diplomacy” with European countries and with Russia and China – partners in the nuclear agreement. Presumably in the period between Biden’s inauguration and the June 2021 elections in Iran, if the United States and Iran wish to renew their dialogue, what are possible are mainly initial confidence building measures, without deep deliberations on the existing substantive problems. Biden has already lifted the ban on visits to the United States by citizens of certain Muslim countries, among them Iran, and there is talk about improved routes for bank purchases of food and drugs, and possibly also a partial release of frozen Iranian funds for this purpose.

The Biden administration’s desire to resume dialogue with Iran, and especially to ensure a rollback of Iran’s nuclear program, are likely to prompt a “hard-to-get” attitude from Tehran, especially in the absence of a substantial easing of the sanctions. Lack of progress is also liable to have an impact on the policy of Iran and the Shiite militias in Iraq, which have expanded the range of their independent activity since Soleimani was killed. These militias and Iran may well test areas of flexibility vis-à-vis the new administration in Washington, and signal the possible price of an absence of dialogue.

Policy Recommendations

- First, Israel must decide how to approach the stated objective of President Biden and the United States’ European partners to return to the nuclear agreement as their preferred way of halting progress in Iran’s nuclear program.

- Israel would do well to define and present its interests, but should refrain from an absolute rejection of the dialogue in order to avoid a conflict with the administration.

- Israel should strive to convince the Biden administration not to abandon the sanctions leverage, or even to return to the original nuclear agreement in the first stage in exchange for Iranian willingness to resume negotiations. An effort should be made to persuade Washington to use the sanctions leverage to enable an extension and improvement of the nuclear agreement.

- In the interim period before Biden takes office, it is important to refrain from provocative measures, in order to avoid damaging trust among the incoming administration, which could have a negative impact on Israel’s ability to influence Iran’s future activity.

On regional issues, it is important for Israel to underscore its policy toward Iran in the Syrian theater, convince Washington to deliver a clear warning to Iran not to take action against Israel in retaliation for the killing of Fakhrizadeh, and encourage the new administration to restate publicly its support for Israel’s national security, with an emphasis on Israel’s right to self-defense. Israel currently enjoys greater understanding of its security interests as a result of Iran’s nuclear ambitions and regional policy, and due to the danger of an arms buildup by Iran and its proxies in the region, which includes advanced missiles and weapon systems. This understanding is an important basis for agreement between Jerusalem and the Biden administration, as well as with European countries. Israel should conduct firm talks in these contexts, with the requisite sensitivity.

In conclusion, the nuclear question should be at the top of Israel’s priorities. With all their importance, the regional issues – led by Iranian intervention in Syria and Lebanon – are of secondary importance. It is preferable not to put them in the same category as the nuclear issue in order to avoid an unnecessary loss of time.