The Operational Environment: Superiority Challenged by More³ – Operational Arenas, Weapons, and Actors

Dror Shalom

Trends

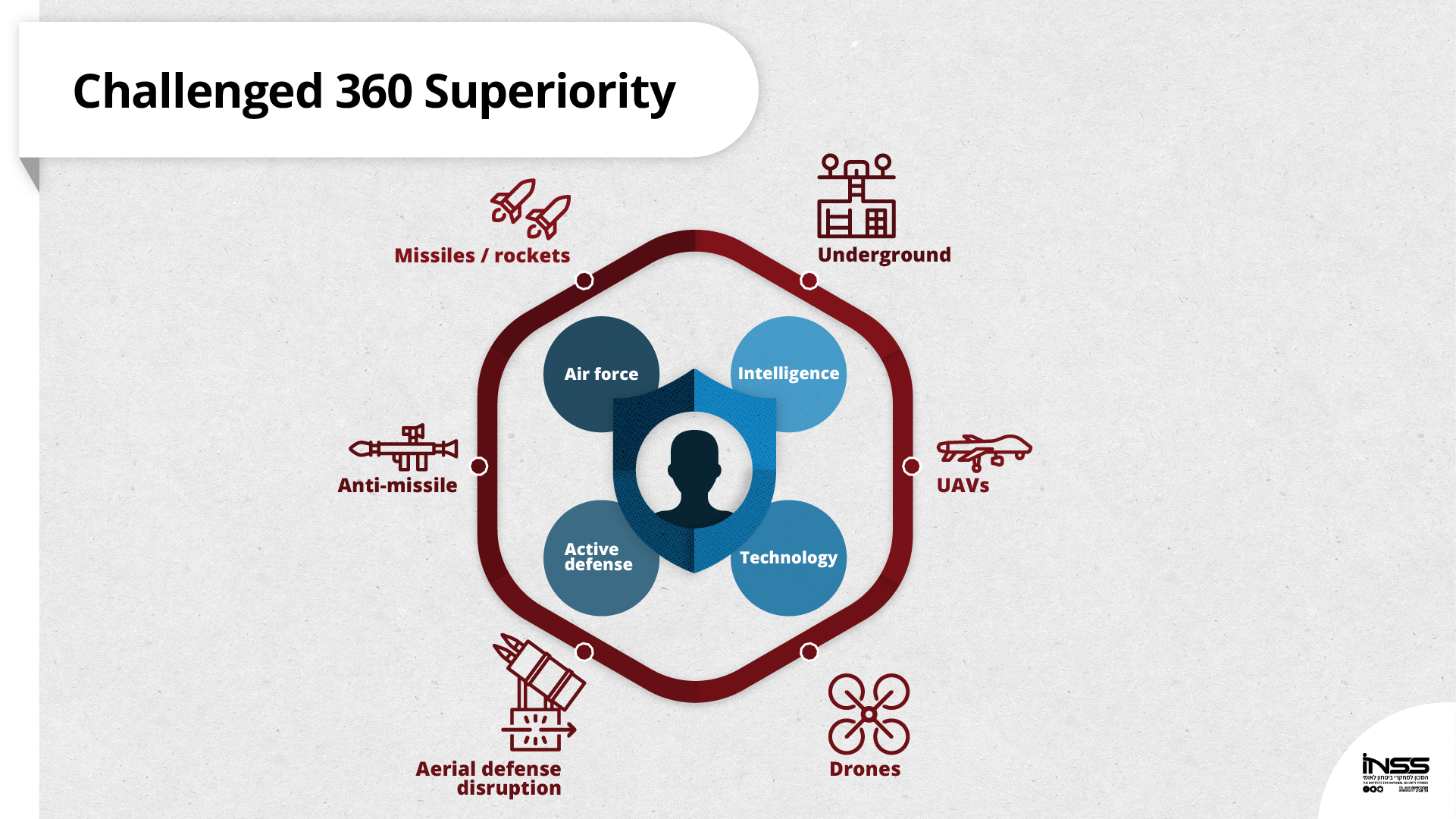

Clear but challenged Israeli superiority · Significant improvement in enemy firepower capabilities, in quantity, lethality, and precision · Israel faces more arenas of operation, more enemies, and more advanced weapons

The Operational Environment: Superiority Challenged by More³ – Operational Arenas, Weapons, and Actors

Dror Shalom

Recommendations

Implement the Tnufa multi-year plan · Strengthen military capabilities for action against Iran · Adapt the campaign between wars to the regional campaign against Iran · Prepare for battle days and a multi-arena war · Improve home front defense and preparedness

Overall, Israel is a strong regional power that enjoys clear operational superiority over its enemies due to its strength in intelligence, airpower, and active defense. This was manifested clearly in 2021 in Operation Guardian of the Walls (attacks on Hamas’s underground and active defense), in the campaign between the wars (reducing the Iranian entrenchment in Syria), and in routine security measures in the West Bank. The Tnufa multi-year plan is also meant to improve the IDF’s operational capabilities for war scenarios, along with neutralization of the threat of attack tunnels, identification of more potential targets, and intelligence and firepower adapted to the information and artificial intelligence era.

However, force buildup among Israel’s enemies reflects a clear learning curve, which in turn offsets Israel’s strength based on their improved defensive capabilities – advanced anti-aircraft systems, disruptors, underground spaces, and integration into the urban environment. Even more so are the enemies’ improved offensive capabilities – more operational dimensions and arenas, and better firepower: in quantity, quality, lethality, and especially precision. With the potential for a turning point in the nature of the confrontation, there is a need for a mental leap (from knowledge to awareness) regarding the intensity of the threat, to the point of examining the possibility of future preemptive action.

Consequently, it is essential to continue to invest in upgrading the capabilities of the IDF and the other security forces through a systemic perspective that is customized to changes in the strategic and operational environment. The immediate focus should be on creating a credible military threat vis-à-vis Iran, not only as to the nuclear program but also regarding a large-scale war in the north. In tandem, the campaign between wars should be continued, expanded, and adapted to the entirety of the Iranian threat, while deepening defensive and offensive cooperation with other actors in the region. In addition, Israel should launch a campaign between wars vis-à-vis the military buildup in the Gaza Strip; prepare for scenarios of deterioration or collapse of the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank particularly once Abu Mazen departs the stage; strengthen the 360° defense of the home front, in light of the potential of a “counter campaign between wars” and a prolonged multi-arena war; engage in political-military discussion to plan maximization and priorities in the case of battle days in the north; formulate an up-to-date strategic objective for the scenario of a war in the north; create mechanisms for controlling the Gaza Strip in a scenario where Hamas is toppled, the organization collapses, or there is a severe humanitarian crisis; and consider how to gain legitimacy and maximize achievements given an accelerated international stopwatch in the case of massive IDF strikes in the urban environment.

Significant processes of change are underway in Israel’s operational environment, in part due to the dynamics and consequences of changes in the strategic environment. Foremost among the shifts in the strategic environment are: regional upheaval, and an erosion of the image of American power alongside the Russian presence in the region; the information revolution and developments in the field of missile precision, miniaturization of computing and technological components and unmanned vehicles; and the regional field of struggle, which enables a learning curve and experience using new weapons in the kinetic and cybernetic dimensions for offense and defense.

Overall, Israel is perceived as a strong regional power, especially due to its operational strengths – its clear superiority in intelligence and cyber tools, airpower, and active defense (Iron Dome). These were also evident in 2021:

- In Operation Guardian of the Walls, despite the complex balance sheet on the strategic level, on the battlefield Israel again demonstrated unique attack capabilities in Hamas’s underground medium (even if the achievement was less than expected), and succeeded in thwarting all of the ground initiatives from within the territory of Gaza while Iron Dome provided significant protection, despite the many barrages of rockets.

- In the campaign between wars, Israel continued to score many achievements in curbing the Iranian entrenchment in the Syrian theater (and certainly in relation to Iranian intentions), while demonstrating, as in the past, the ability to carry out precision strikes on Iranian infrastructure and advanced weapons brought to the region. The implementation of the campaign between wars is possible due to a combination of political activity (dialogue with Russia) and military activity that manifests advanced intelligence and air force capabilities.

- In routine security measures, the IDF continues to demonstrate high-level capabilities to thwart distant threats and border threats in a variety of dimensions (in the air, at sea, and in cyberspace), all while continuing the joint activity of the IDF and the Israeli Security Agency to prevent terrorism in the West Bank.

Capability to strike Hamas underground. Underground tunnel exposed in Gaza Strip

From a broader perspective, the Tnufa multi-year plan stands to improve the IDF’s operational capabilities for war scenarios, with the need to neutralize the threat of offensive tunnels (in the Gaza Strip and Lebanon), identify enhanced targets in both quantitative and qualitative terms, and improve intelligence and firepower capabilities toward significant damage to Hezbollah’s capabilities in Lebanon. There is also a need to sharpen capabilities for striking Iran (and not only nuclear sites); continued upgrade of intelligence capabilities in the information, artificial intelligence, and cyber era; enhancements of active defense; and continued acquisition of interceptors and honing offensive capabilities, particularly when it comes to connectivity between command and control, intelligence, and all components of firepower.

At the same time, there is an ongoing trend in which Israel’s operational superiority is offset. In the background are the technological revolution, which allows for easier access to knowledge for developing advanced weapons (copying and reverse engineering); the miniaturization and “civilianization” of computing capabilities, detection, disruption, and lethality; and the fact that the Middle East is a field of struggle (not just between Israel and its enemies) that enables the accumulation of operational experience and trials that accelerate the mutual learning curve in offense, disruption, defense, and cyber.

In many senses, Iran is the element leading the operational learning curve with Israel. It enjoys advanced capabilities in research and development (human capital and advanced technological capabilities), and its outstretched tentacles elsewhere in the Middle East – Quds Force, proxies, and allies – gain experience and knowledge from the friction with Israel and the Gulf states in routine times and during escalation. In practice, the growing capabilities of Iran, Hezbollah, Hamas, and Islamic Jihad reflect accelerated development that strives to offset Israel’s sources of strength in several main areas.

Offensive Capabilities: Firepower³ – More Quantity, More Quality, More Precision

There are continued efforts toward the accelerated development of capabilities to harm the Israeli home front and the maneuvering forces using advanced firepower capabilities. Thus, alongside the effort to increase the quantity, which in itself is a qualitative development, there is a prominent effort to increase the damage capacity by developing larger warheads with greater destructive capability (including heavy rockets in the hands of the terrorist groups in the Gaza Strip) and above all, to develop precision fire capability. In many senses “the precision is already here,” as for some time Iran has been converting many rockets into precision missiles, and Hezbollah too, with Iran’s help, has maintained its determination to develop an independent capability to produce and convert precision missiles in Lebanon, despite Israel’s preventive efforts in the campaign between wars. Progress on this in Lebanon, and certainly possible success in converting hundreds of rockets into precision missiles in the future, would pose a serious strategic threat to Israel, which would accentuate the dilemma regarding preemptive action.

The era of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and drones: There is increasing experience with autonomous weapons, explosive drones, and UAVs. Iran and its proxies have earned much knowledge, capability, and experience in operating low-signature explosive UAVs over long ranges, and these tools are seen by Tehran as a (relatively) precise means of attack that enables operating under the threshold of war.

Challenge to the Iron Dome: Operation Guardian of the Walls provided further evidence that escalation in the Gaza Strip serves as a learning and testing ground for Israel’s enemies in a variety of fields, foremost among them the effort to identify vulnerabilities in the Iron Dome system. Hamas continued its attempts to challenge Iron Dome systems by means of timed barrages, swarm barrages to empty out the batteries of interceptors, and fire from a variety of areas directed toward one target. Overall, Hamas failed in practice to cause the damage that it wished, but it is essential to consider the complexity of the challenge to Israel’s defensive systems in scenarios of intense and prolonged war in the northern arena or on several fronts simultaneously.

Growing use of explosive UAVs. Launch of UAV during Iranian army exercise

Photo: Iranian Army/WANA (West Asia News Agency)/Handout via REUTERS

Defense: Anti-Aircraft Systems, Disruption, Integration into the Urban Environment, and Descent Underground

In the field of defense, the goal is to erode Israel’s superiority in the aerial dimension through an effort to introduce advanced anti-aircraft systems to reduce the air force’s freedom of operation in the skies above Lebanon – which could also lead to a miscalculation and to escalation; an effort to increase the campaign over the aerial spectrum through disruption efforts and aerial warfare in the Syrian sphere; and the continued development of capabilities in Lebanon and the Gaza Strip to challenge the maneuvering capabilities of the IDF’s ground forces by creating a comprehensive threat that includes advanced anti-tank missiles (precision guided and longer range), bouncing bombs, and explosive drones.

Joining these is the ongoing trend of going underground. Despite the capabilities that Israel has demonstrated in locating, neutralizing, and striking the underground medium, this dimension continues to be seen as the optimal way to defend against Israel’s precision strike capabilities. The main purpose is protecting high-quality weapons, weapons production facilities, command posts, and in Iran, the operation of advanced centrifuges. All of this is against the backdrop of continued integration into the urban environment while using the population as a human shield, especially in Lebanon and the Gaza Strip.

360° threat: It appears that under the influence of the campaign between wars against Iran’s entrenchment in Syria and the counter-reactions of Iran and its proxies, the IDF, more than in the past, must defend and attack in more arenas and in more dimensions. Thus, alongside the familiar threat from the northern sphere, the Gaza Strip, and the West Bank, Israel must take into consideration intelligence, defense, and attack capabilities in additional arenas, including Iraq (Israel has already thwarted attack attempts from this region), possibly also Yemen (the Houthis’ threats against Israel and the weapons transferred there from Iran), in the maritime medium (especially against the backdrop of the series of attacks carried out by Iran against vessels Tehran thought belonged to Israel), and in the cyber realm (used increasingly by Iran against targets in Israel). Meanwhile, Israel must recognize that in the scenario of an all-out war, it might need the capability to attack and defend simultaneously on several fronts, including in Iran itself.

Deployment in the urban space. Rockets launched at Israel from a civilian area in southern Lebanon, August 2021

Photo: REUTERS/Karamallah Daher

Currently there is no immediate threat of unconventional weapons. Nonetheless, on the agenda is Iran’s attempt to achieve nuclear capability, and the possibility of its becoming a “threshold state” already increases the motivation of Sunni countries (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey) to achieve such capabilities. Thus in many respects, even if there may not yet be a nuclear arms race in the Middle East, the “nuclear crawl” has presumably already begun, and more in-depth research on the issue is necessary. In the realm of biological and chemical weapons: there is no significant threat at this time, but it is clear that Israel should presume that residual capabilities exist in Syria, and should more closely track the possibility that Hezbollah will arm itself with dangerous substances (anesthetic substances, for example) as part of its experience from fighting alongside the Syrian regime.

The Slippery Slope of Perceptions: Campaign between Wars, Battle Days, and War

The many strikes carried out by Israel in the campaign between wars in recent years in the northern arena (alongside neutralization of the Hezbollah and Hamas tunnels) considerably reduced the capabilities of its enemies, without deteriorating to the point of high-intensity war. Furthermore, the campaign between wars in the northern arena also granted Israel strategic leverage for possible influence (at least vis-à-vis Russia) and strengthened its image of deterrence in the region. That said, the campaign between wars accelerates the enemy’s learning curve, leads to improvement of its disruption and defense structure, and its response attempts – whether from within the Syrian sphere or from Iraq, by sea or in cyberspace. All these significantly increase volatility, potential for miscalculation, and the risks of the conflict expanding to other sectors (for example, Lebanon).

Furthermore, it appears that in the past few years, Israel’s enemies, which on the one hand are deterred from war but on the other hand assess that Israel is also deterred from conflict, have begun to examine responses/proactive measures under the threshold of war (a kind of counter campaign between wars), under the assumption that mutual deterrence will lead to exchanging blows, limited to a few battle days. This possibility requires strengthened deterrence against such an approach or the effort to reach swift achievements (e.g., precision), in the case that such a scenario takes place and Israel still prefers to avoid a large-scale escalation.

It is doubtful that one of Israel’s enemies will be interested in initiating a large-scale war in the coming year. Nonetheless, war as a result of a miscalculation remains a possibility. Furthermore, given the increasing connections between the various arenas, one cannot rule out a multi-arena war scenario. For example, unlike in the past, in the north, Iran’s entrenchment efforts in Syria (Quds Force, militias, firepower capabilities) increase the likelihood of escalation expanding from Lebanon to the Syrian sphere, including attack attempts from Iraq, Yemen, and Iran itself. Similarly, there is greater likelihood that in the scenario of a war in Lebanon, the Palestinian terrorist organizations in Gaza (especially Islamic Jihad) will also try to challenge Israel; and in scenarios of escalation in Gaza, there will be increased risk of a deterioration in the West Bank and vice versa (especially if the Palestinian Authority continues to weaken). All of this could occur against the backdrop of volatility vis-à-vis extremist elements among the Arabs in Israel in any scenario of war.

Policy Recommendations

Israel still enjoys operational superiority in the Middle East, but this is eroding and requires ongoing updates and an upgraded forward-looking systemic perspective.

- First and foremost, Israel should maintain the Tnufa multi-year plan, build a credible military threat against the Iranian challenge – its nuclear program, entrenchment, and government institutions, and prepare for a large-scale war in the north.

- In addition, Israel should continue with the campaign between wars to offset enemy capabilities; this does not obviate preparedness against Iran. On the contrary, it appears that the campaign between wars strengthens the intelligence and firepower muscle, but it is essential to expand it and to adapt it to the entire Iranian challenge in the Middle East, i.e., to actions under the threshold of war in a wider area against Iran and its proxies, while deepening the partnerships and coordination for defense and offense with other regional actors (with an emphasis on the Gulf countries).

- There should be a strategic political-military dialogue for optimal utilization of battle days without a war (especially in the context of the missile precision project in Lebanon) and for formulating a fresh strategic objective for war in the north (i.e., the desired security arrangements for Israel in all of Lebanon, in Syria, and on the border between them) and the question of operation in the presence of Russian forces.

- In addition, Israel should broaden the campaign between wars against the military buildup in the Gaza Strip: not only within the territory of Gaza, but also in the supply chain (development and production personnel, shipments, production infrastructure). In a related context, Israel should prepare for scenarios of deterioration or collapse of the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank once Abu Mazen departs the scene.

- Furthermore, the 360° defense of the home front must be strengthened in light of the potential for prolonged multi-arena war.

- Mechanisms for maintaining the Gaza Strip must be formulated for a scenario in which Hamas is toppled or it collapses, and in case of a large-scale escalation or a severe humanitarian crisis.

- Finally, Israel should consider how to earn legitimacy and maximize achievements vis-à-vis an accelerated international stopwatch in face of massive IDF strikes in the urban environment, which would inevitably lead to many civilian casualties, especially in Lebanon.