Iran: Toward a Nuclear Crisis or a Nuclear Threshold

Sima Shine, Raz Zimmt, and Ephraim Asculai

Trends

The nuclear program is very close to a possible breakout, subject to Tehran’s decision · It is uncertain under what conditions the JCPOA might be renewed · Iran’s new conservative president, Raisi, continues to pursue regional entrenchment

Iran: Toward a Nuclear Crisis or a Nuclear Threshold

Sima Shine, Raz Zimmt, and Ephraim Asculai

Recommendations

Prepare for the lack of a nuclear deal, Iran reaching the nuclear threshold, and perhaps a breakout · Maintain regional freedom of operation, and the campaign between wars · Continue to obstruct the nuclear program and coordinate with the US

In 2021 Iran saw a change of president and government; rounds of talks that did not produce a return to the nuclear deal; an intensified confrontation with the IAEA; strengthened relations with China and Russia; and initial talks to improve relations with the Gulf states. At the same time, Iran experienced increasing difficulties in Iraq and Lebanon; and continued activities attributed to Israel against the nuclear program and against the transfer of weapons to Syria and Hezbollah, as well as at sea and in the cyber realm.

In the coming year Iran could face a strategic decision – a return to the nuclear deal while arresting progress on the program, or alternatively, tension and conflict with some in the international arena and progress toward becoming a “nuclear threshold state.” Facing Iran’s nuclear program, Israel is in a strategic quandary: the various possible scenarios, whether a partial agreement or continued foot-dragging or a breakdown in the negotiations, are negative for Israel. This backdrop highlights the need to maintain an intimate dialogue with the United States administration and formulate a comprehensive strategy for the coming years that includes a credible military threat and multi-faceted pressure on Iran; elimination of the advanced components of the nuclear program, if necessary; an extensive campaign between wars to curb Iran’s regional entrenchment, and not only in the Syrian realm; and use of the Abraham Accords to create a regional and international alliance to restrain Iran and strengthen deterrence against it. Conversely, a public conflict with Washington would weaken Israel and play into Iran’s hands: the statements about preparing a military option would not appear credible, might erode deterrence, and could push Washington to pursue an even worse agreement.

From Israel’s perspective, the following are preferable: a return to the agreement that buys Israel time to prepare an alternative; maintained freedom of operation in the regional arena; continued obstruction of aspects of the nuclear program; and coordination with the United States on future developments.

The Domestic Arena

The political system: The June 2021 election of hardliner cleric Ebrahim Raisi as president marked the completion of the conservative camp’s takeover of the country’s political institutions. The regime’s blatant intervention in the election process – the disqualification of candidates and steps to guarantee a clear achievement in the first round – were another expression of the continued autocratization of the regime and its determination to keep out any element that could threaten conservative hegemony, especially in advance of the succession struggle over Iran’s leadership. The makeup of Raisi’s government, some of whose ministers tout a radical and anti-Western ideological line, attests to the president’s intention to adopt a stricter stance in domestic and foreign affairs than that of the preceding Rouhani government, in accordance with the strategy set out by the Supreme Leader.

The economic sphere: After over two years of an ongoing and intensified economic crisis against the backdrop of economic sanctions, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the drop in oil prices, a mixed trend was evident last year in Iran’s economic situation. On the one hand, there were initial signs of economic stabilization and even recovery, reflected in light economic growth (2.5 to 3 percent, according to World Bank and International Monetary Fund estimates), a decline in the unemployment rate (close to 9 percent), and a significant rise in foreign currency reserves (from $12.4 billion in 2020 to $31.4 billion, according to an IMF estimate).The recovery stems primarily from success in exporting oil (mainly to China) at a rate of over a million barrels a day; a gradual exit from the COVID-19 crisis; and a rise in oil prices. On the other hand, Iran faces a worsening inflation crisis (between 45 and 50 percent annual inflation), an increasing budget deficit, increased poverty, and capital flight.

In the coming year, even if the nuclear deal is restored and the sanctions are removed, a significant economic improvement is unlikely due to the uncertainty regarding the policy of the next administration in Washington, the fact that most European companies do not intend to return to do business with Iran, and the structural problems that plague the Iranian economy (corruption, Revolutionary Guards involvement in the economy, and the continued Iranian refusal to implement the FATF regulations). In a scenario of continued and increased sanctions, the economic crisis is expected to worsen, although it seems that the regime is capable of weathering it by circumventing the sanctions, relying increasingly on China, and continuing to adapt the economy to the sanctions regime (“resistance economy”).

Signs of economic recovery despite severe inflation. Crowded market in Iran

Photo: Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto

The social arena: Most of the past year was characterized by relative calm compared to the waves of protests that swept Iran from late 2017 until early 2020. This is mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which inhibited gatherings, and increased efforts at control and suppression by the authorities. However, the waves of protest in the summer of 2021 against the backdrop of water and electricity shortages indicated that the lack of an infrastructural solution to civilian hardships and the economic crisis continue to provide fertile ground for renewed protests in the coming year as well.

The Regional Arena

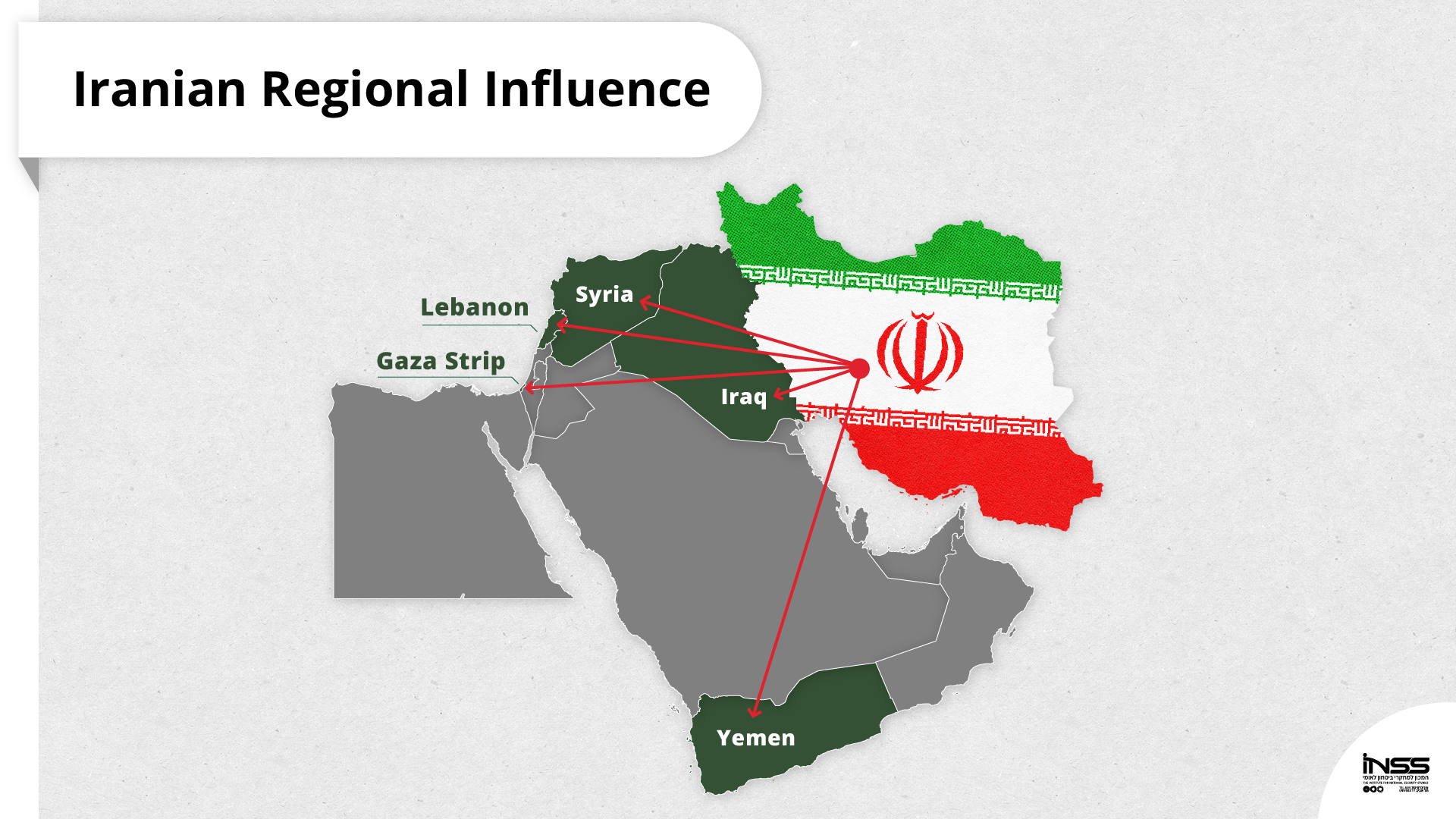

Over the past year Iran faced increasing difficulties in the regional arena. While the withdrawal of the US forces from Afghanistan was presented as a positive strategic development, the Taliban’s renewed takeover poses a significant challenge to essential Iranian military and economic interests. In Iraq the pro-Iranian Shiite militias suffered a serious defeat in the parliamentary elections, and there is a growing impression that the Revolutionary Guards’ control over the militias has weakened. This development, in addition to Baghdad’s efforts to improve relations with the Sunni Arab countries, is a sign of the challenges facing Iran and its proxies in the country. In Lebanon, Hezbollah is confronted with criticism of its performance and Iran’s increasing influence in the country, even as Tehran continues to provide supplies and oil through the organization. In Syria the attacks conducted overtly by Israel (and those attributed to it) have posed a significant challenge for Iran, although they have not led it to halt its efforts to transfer advanced weapons to Hezbollah. Given the ongoing efforts toward an arrangement in Syria, the process of reducing the Iranian and foreign Shiite forces in Syria also continues, alongside the increasing entrenchment of Syrian fighters who are recruited to militias supported by Iran. Meanwhile, there seems to be slow progress in economic projects in Syria and continued isolated efforts by Iran to expand its social, cultural, and educational influence in the country. In Yemen the military aid to the Houthis continues, as part of the war waged against Saudi Arabia, which has been attacked by missiles and UAVs. In the Caucasus too, Iran has faced significant challenges against the backdrop of Azerbaijan’s victory in the military conflict with Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh region, Azerbaijan’s strengthening relations with Israel, and the increasing Turkish influence in the region. All these challenges notwithstanding, Iran continues its efforts to advance its long-term interests in the region, while adapting its policy to the changing circumstances.

Meanwhile there is an unfolding process, begun during Rouhani’s term, to reduce tension and improve relations between Iran and its Gulf neighbors. This process reflects the Gulf countries’ understanding that the United States continues its disengagement from the Middle East as it negotiates with Iran on returning to the nuclear deal, which, if achieved, will strengthen Iran politically and economically. In parallel, the process reflects the Iranian desire to reduce tension with its neighbors as part of a policy of striving for regional dialogue without Washington’s participation and as a response to the demand to connect the discussions on the nuclear issue with Iran’s regional policy. The United Arab Emirates plays a major role in this context, as it constitutes an important trade route for Iran. Notable in this context was the visit to Tehran by the Emirati National Security Advisor and brother of the Crown Prince. A fourth round of talks with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s main rival, also took place in Iraq and with Iraq’s mediation, but at present there is no breakthrough in relations between the countries.

The conflict between Israel and Iran continues and has intensified in the past year, expressed in preventive activity attributed to Israel against the nuclear program; the Israeli strikes in Syria, which have increased as part of the ongoing effort to thwart the Iranian military entrenchment and weapons transfers to Hezbollah; the struggle in the naval realm, with some 12 Iranian vessels reportedly damaged, and the publicity surrounding these attacks, which led to Iranian attacks on merchant ships connected to Israel; mutual cyberattacks – from the Iranian side, attacks on civilian companies while publicizing the information as part of cognitive operations (at this stage at a relatively low level), and disruptions, attributed to Israel, at the port of Bandar Abbas, of flight schedules and of smart cards for purchasing gasoline. Concurrently, lacking the ability to strike Israel directly and significantly, in the past year several attempts to carry out terrorist actions against Israeli figures in the international arena were exposed and thwarted. In addition to the regional activity, increasing trends are prominent in Iran’s global foreign policy, chiefly a strategic decision to rely politically, militarily, and economically on Russia and China. In this framework, a 25-year strategic partnership agreement was signed with China (March 2021) and a strategic partnership agreement with Russia was renewed; in September 2021 Iran was accepted as a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO); and several joint naval exercises with Russia and China were held. These measures strengthen the conservative camp led by the Revolutionary Guards, which consistently supported this direction, over the Rouhani camp, which preferred to strengthen relations with the West. They help Iran cope with the sanctions and strengthen its international standing, including with respect to future IAEA measures and at the UN Security Council.

The Nuclear Program and Negotiations on Returning to the JCPOA

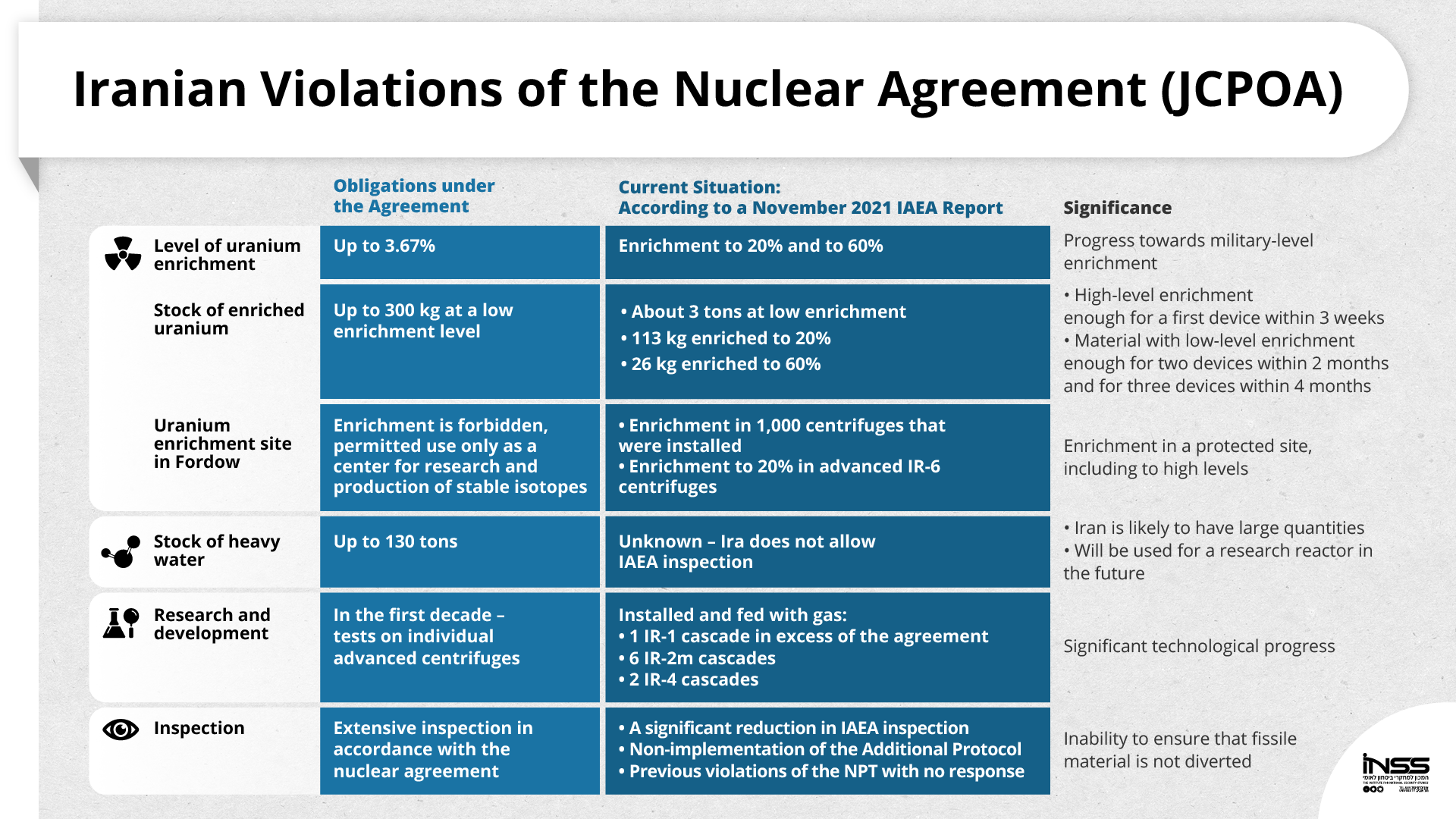

Iran began violating the nuclear deal in May 2019, in response to the United States’ withdrawal from the agreement. Since then, according to the most recent IAEA report, the most significant and unprecedented progress in the program occurred in the past year. The amounts of uranium enriched to 20 and 60 percent are sufficient for high-level enrichment of fissile material for a first nuclear device within three weeks; if Iran also decides to enrich the material enriched to approximately 5 percent to a military level, it will take two months to amass enough fissile material for a second nuclear device, and three and a half months for fissile material for a third nuclear device. Meanwhile, the production of 20 percent uranium metal (a critical component of nuclear weapons) is underway; the enrichment of uranium to 20 percent using advanced centrifuges at the Fordow site has begun; and IAEA supervision has been drastically reduced – both according to the Additional Protocol and according to the nuclear deal. These figures led the IAEA Director General to declare that “the lack of progress in clarifying the Agency’s questions concerning the correctness and completeness of Iran’s safeguards declarations seriously affects the ability of the Agency to provide assurance of the peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear programme.” All this compounds the continued lack of Iranian cooperation on questions related to undeclared uranium found at four undeclared sites (a violation of the inspection agreements). It appears that the explosive device (the second principal component in the development of a nuclear weapon) is under development at these sites. According to estimates, Iran will be able to conduct a nuclear test within six months from the moment it takes a decision to do so. However, the third stage of the project, fitting the explosive device for launch (by plane or missile) will take another few years.

Significant progress in the Iranian nuclear program. Former Iranian President Rouhani inspects centrifuges on National Nuclear Day

Photo: Iranian Presidency Office/WANA (West Asia News Agency)/Handout via REUTERS

In the past year Iran also suffered significant blows: first and foremost, the assassination of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh (in late 2020), who was the leading figure and organizer of the nuclear program and controlled all its components and enjoyed a direct and intimate connection with the Supreme Leader; and while less significant, damage to the centrifuges at the Natanz enrichment site (April 2021), and damage to the centrifuge production site at Karaj (June 2021).

Aside from repairing the damage and transferring the damaged facilities underground, Tehran chose to respond through a series of measures regarding the nuclear program, chiefly the Majlis bill that in effect “requires” that the state move forward with high-level enrichment and take all necessary steps to progress with the program, as well as reduce IAEA supervision. Thus, in responding to the damage at Karaj, Iran prevented inspectors from entering the site and from accessing camera footage. After a hiatus, the talks between the partners in the nuclear agreement and Iran and the United States were renewed under President Raisi, but in different conditions and with stringent positions and demands that at this stage are not acceptable to Washington and the European partners.

Four possible scenarios in the coming year: reaching an agreement to return to the JCPOA within a short time frame – low probability; continued discussions and foot-dragging for many months, but without admitting failure – medium probability; an interim agreement – less for less – at present Iran refuses, but there is some probability that the sides would agree; or not reaching an agreement, ceasing meetings, and beginning to implement steps against Iran (even if in practice the sides continue to present an open diplomatic path) – medium probability.

Among the four possible scenarios, none of which are good for Israel, the worst is the lack of an agreement and Iran progressing in its nuclear program. The US administration (like Israel) does not have a political alternative, other than sanctions, which Iran has learned to cope with; the gaps between the red lines of Israel and the United States, which stem from the differences in perceptions of the threat as well as capabilities, heighten the tension between Jerusalem and Washington. There is no American willingness for military action, except perhapsin the scenario of a clear Iranian nuclear breakout; Israel could be left alone against an intensifying threat that is too great for it.

Under these complex circumstances, a return to the nuclear deal is preferable for Israel, on the condition that it does not permit Iran’s technological violations since the May 2018 withdrawal, and that despite the knowledge and experience that Iran has accumulated, will provide a few years to prepare an alternative. Israel must take into consideration that its friends in the Gulf will toe the line with the US administration, and they have indeed expressed support for a return to the nuclear deal, while also pursuing dialogue with Iran. Considering that returning or not returning to the agreement currently depends mainly on Iran, and the chances of not returning are similar to and perhaps greater than the chances of reaching understandings that would enable returning to the agreement, it is preferable for Israel to reach understandings with the United States on its essential interests – freedom of operation in the region, continued preventive action against the nuclear program, albeit sparingly and pursuing only high priority actions, and understandings regarding possible developments in the future.

The bottom line: the nuclear program’s progress gives Iran the shortest nuclear breakout time in recent years, if it decides to pursue this option. From Iran’s perspective, the more it progresses, the greater the temptation is not to return to the agreement without more significant compensation, which is doubtful whether Washington has the ability/desire to provide.

Against this backdrop, Israel is in a strategic quandary. The various possible scenarios, whether a partial agreement or continued foot-dragging or a breakdown of the negotiations, are negative for Israel. This situation highlights the need to maintain an intimate dialogue with the US administration that enables formulating a comprehensive strategy that includes a credible military threat for the coming years and pursuing multi-dimensional pressure on Iran; thwarting advanced program components if necessary; waging an extensive campaign between wars to curb Iranian entrenchment, and not only in the Syrian realm; and, making use of the Abraham Accords, forging a broad regional and international alliance to restrain Iran and strengthen deterrence against it.