Military Power: Overhauling the IDF and Adjusting Its Missions

Ofer Shelah, Tamir Hayman, and Liran Antebi

Military Power: Overhauling the IDF and Adjusting Its Missions

Ofer Shelah, Tamir Hayman, and Liran Antebi

Summary chart

Current Situation

Gaps between service branches · HR challenges in compulsory, standing, and reserve service · Inadequate response for a multi-arena scenario

Current Israeli Strategy

Military buildup based on options and precedents · No decisions on fundamental questions, particularly regarding ground forces

Israel’s Strategic Gap

Ground forces lag technologically and conceptually behind the air force and Intelligence · HR model ignores changes in the threat and in society · Doubts regarding required achievement in a multi-arena scenario

Alternatives to Existing Security Policy

- Defense in cooperation with others – defense pact with the US, NATO, or countries in the region This is only theoretical – not politically feasible and contradicting existing defense doctrine

- Significantly expanding the security budget and linking it to GDP This would harm economic and social growth in Israel

- Adapting military buildup to a multi-arena scenario, within current spending limitations Updating model of the “people’s army”

Recommended Strategy

Define the achievement required in a multi-arena conflict, and the role of each security body · Update the operational doctrine · Budgetary changes within limitations of current security spending · Draft action plans and military buildup accordingly

Recommended Action

“Critical mass” military buildup, including “soft” efforts · Ground forces buildup in offensive formations, defensive formations, home front forces, and special forces · Strengthen stand-in forces in the air, interception systems, and remote fire · Develop the space realm · Update General Staff structure and strengthen regional commands · Change HR structure according to the multidimensional service model · Approve a multiyear budget and multiyear plan · Prepare for Iranian and regional nuclearization

Israel’s security bodies, above all the IDF, are large and complex. By nature of their respective structures and functions – the continuous task of defending the country and constituting an insurance policy for cases that cannot necessarily be foreseen – their development has been evolutionary, while minimizing risks and avoiding upheaval with unknown effects. However, a number of seminal developments mandate a thorough assessment of these essential organizations, in the realization that changes must be made, albeit in a careful and responsible manner. As early as 2015, then-IDF Chief of Staff Gadi Eisenkot stated that the IDF had “to make a substantial change for the purpose of adapting itself to future challenges and the nature of modern wars and conflicts, and to make more effective use of its resources” (“Gideon: Why and How,” Maarachot, 471). This directive is even more urgent following four years without an approved multiyear plan and budget.

The Changes that Mandate Deployment Adjustment

- A change in the nature of the threat and the challenge: The IDF was built with enormous investment for scenarios of a massive conflict on Israel’s borders. This threat has not been eliminated, and the possibility of rapid changes in this unstable region must not be ignored. Now, however, it is necessary to prepare for a complex conflict on multiple fronts that will require simultaneous operations in distant theaters, along Israel’s borders, and within the country itself – attacks on the home front and internal clashes, as occurred during Operation Guardian of the Walls.

It is necessary to prepare for a complex conflict on multiple fronts. Training for combat in urban areas

Photo: IDF Spokesperson’s Unit (CC BY-NC 2.0)

- Changes in war: Conquering and occupying territory are now regarded as a disadvantage, not a means of achieving victory; the enemy is hidden within the civilian population, which limits operations; a significant part of the conflict takes place in the cognitive realm, be it among Israelis, populations in areas marked by conflict, and the international community. The war in Ukraine illustrates these changes vividly.

- Technological changes: unmanned weapons in the air, on land, and at sea; the need for cyber defense and the ability to conduct offensive cyber operations; forceful and decentralized firepower; and the advantages of integrated networked operations – all these create new operational possibilities and require defense against new threats on the battlefront and the home front.

- Changes in Israeli society: The sense of an existential threat that has waned, demographic growth in sectors that do not serve in the army, and unresolved political issues all affect the perception of the value of military service and the IDF’s ability to recruit and retain excellent and necessary personnel, and to make full use of the resources needed to defend the country.

- There is an inherent tension between routine activity designed to handle threats such as terrorism and the enemy’s force buildup efforts, and force buildup for a major campaign, especially for the IDF. This tension emerges fully only in such a campaign, and to the greatest extent in the ground forces, which constitute the bulk of the force.

- Most of the units in the operational force engaged in daily operations are employed in the West Bank; their missions are different in nature from their assignments in a full-scale war. In addition, significant emphasis is placed on the campaign between wars, which involves a very small proportion of the force in conditions of maximum intelligence and air power superiority.

- The operational concept dominant in campaigns and the relatively large rounds of conflict, which is mainly defensive standoff action involving mostly firepower while refraining as much as possible from the use of ground forces, prolongs the fighting. This concept is unsuitable for the multifront scenario for which the force is built.

- The emergence of Iran as a nuclear threshold state that requires only a decision and short timespan to attain nuclear capability requires preparation for a situation in which it, as well as other countries in the region, has such a capability.

The emergence of Iran as a nuclear threshold state requires preparation for a situation in which it has such a capability. Centrifuges in Iran

Photo: Shutterstock

Alternatives to the Existing Security Policy

Over the years, a number of alternatives to the existing security policy – involving both underlying concepts and the force buildup needed to meet the challenges – have been proposed.

Countering the idea that Israel should defend itself solely on its own, proposals have arisen for defense alliances with the United States or NATO, or a regional alliance framework with existing or future partners in political agreements who are also under threat from Iran and terrorist groups. Joining defense alliances such as NATO or forming an alliance of this sort with the United States, however, is an unrealistic option, and thorough deliberations are required to consider its true value. Relying on a foreign power also clashes with the nature and tradition of Israel and the IDF, the power derived from the “people’s army” model, and the ability to respond fairly rapidly to possible changes in the region.

One demand has been to amplify security resources, including by setting defense spending at a fixed level of GDP that is much higher than the current percentage. This demand conflicts with the comprehensive view of Israel’s power as an economic and technological force and a country with social needs, all of which impact greatly on national resilience.

Because of the changes in the nature of war and the enemy and the evident reluctance to put IDF ground forces into operation, the possibility has been raised of reducing the maneuvering force to a minimum and relying on the use of standoff force. Building such a force, however, is liable to deny the IDF an important tool for attaining its goals and countering the enemy’s threats, and to impact negatively on preparedness for rapid and far-reaching changes in the region. It will also be difficult and expensive to reverse.

Proposals have arisen for defense alliances with various countries, but thorough deliberations are required to consider the true value of such pacts. Joint exercise of the US and Israeli air forces

Photo: IDF Spokesperson’s Unit (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Nor is the idea of doing away with conscription practical, even if it has arisen in various opinion polls, given the political and social difficulties in making such a change, the evolving personnel needs, and the growth in the induction groups. The IDF’s qualitative edge is based on conscription, because in countries where the military is composed of volunteers, high quality sectors of society do not serve. Furthermore, in any reasonable outline of the threats to Israel, the desired size of the army is too large to be economically viable to maintain a volunteer army on such a scale.

The following proposed changes were therefore designed with the idea that conscription should not be abolished, a large first-rate maneuvering ground force should not be eliminated, partnership with a foreign country in defending Israel should not be relied on, and no major change should be made in the existing resources framework along the lines of the measures taken following the Yom Kippur War.

How to Devise Necessary Changes

Reference scenario – a multifront conflict in all theaters: In this scenario, Israel will have to operate simultaneously in distant theaters against Iran, which will bombard Israeli territory from other fronts beside its own territory; confront Hezbollah’s enormous stockpile of missiles and rockets; and incur a threat of bombardment from the Gaza Strip, while at the same time facing large-scale disturbances in the West Bank and riots within Israel itself.

The necessary achievement must include timetables, recognizing the essential need to limit the campaign’s duration, while ranking the threats and the order in which they will be handled. Shortening the campaign, which is described in IDF strategy as a “permanent imperative” for the army (IDF Strategy Document, 2018, p. 21), is essential in a scenario in which Israel’s home front is subjected to unprecedented bombardment from all ranges. Clear decisions should be made about the order of the victories to be achieved on each front, the army’s ability to achieve a clear victory in each theater, what must be carried out simultaneously, and what must be accomplished in successive steps.

Cyber efforts, covert operations, and legal and cognitive warfare should be integrated to achieve success. Whenever feasible, these modes of operation should replace overt military operations in order to focus on force buildup for real goals and optimize the use of all resources to the greatest possible extent.

Critical “quality mass”: In force buildup, emphasis should be placed on a critical quality mass that can be activated under real conditions, at the expense of a “broad” quantity that remains untapped. In all theaters, the IDF has intelligence, air, and firepower capabilities far in excess of those possessed by the enemy. Israel has also developed pioneering active and passive defense systems for AFVs, air defense systems for forces and airborne jamming of the enemy’s weapon systems, and advanced unmanned systems in the air and on land. Given the expense of these systems, it is impractical and unnecessary to allocate them to all IDF forces.

Shortening the campaign is essential in a scenario in which Israel’s home front is subjected to unprecedented bombardment from all ranges. Damage to a home in Ashkelon during Operation Guardian of the Walls

Photo: REUTERS/Amir Cohen

Ground Forces

The ground forces should be built according to the concept of differentials:

- An operating array deep in enemy territory and special operations, with integration of all dimensions (air, sea, land, and cyber) and credible plans for operational measures that are important for victory.

- Offensive formations: A critical mass will be created capable of operating securely and effectively in enemy territory, reaching every location necessary, and achieving a clear victory in any conflict. In building these formations, the force should be decentralized and given maximum independence, because in a multifront conflict, battalions and brigades will have to operate under conditions of partial intelligence and “traffic jams” in the command and General Staff firepower centers. The offensive formations will utilize General Staff intelligence and firepower capabilities but will not be dependent on them for operations. They must be capable of operating independently in the territory assigned to them, while using a “ground-controlled air fleet” of aircraft (primarily unmanned) and firepower capabilities under its own control. This principle will uphold the independent command and initiation concept that constitutes the spirit of the IDF. Preparations should also be made for the use of firepower and unmanned capabilities by the enemy.

- Defensive formations will protect Israel’s borders and border communities, and will operate in areas close to the border in order to improve the tactical position, while utilizing capabilities prepared in advance and made available to them. These formations will include forces that will act to prevent attacks against Israelis and maintain freedom of action in the West Bank in the event of a large-scale conflict.

- Home front forces include policing and anti-terrorism forces in the West Bank and within the Green Line, the Home Front Command, Israel Police, and the Israel National Fire and Rescue Authority. These forces will defend the lives of Israelis, limit damage to the home front as much as possible, treat the injured, and preserve order. These agencies should be reinforced, while additional personnel and money should be allocated for strengthening the Border Police, Israel Police, and other bodies.

Air Force, Space, Firepower, and Cyberwarfare Capabilities

- The air force should focus on force buildup for defense of the nation’s skies, attacks on enemy strategic and systems targets, and jointness in the ground battle in places where “heavy” air weapons are needed for firepower, transportation, logistics, and evacuation. The air force should build “stand-in” capabilities that will enable it to attain air supremacy and utilize its capabilities in any location.

- At the same time, operations in outer space, where Israel enjoys a large advantage over its enemies, should be developed and strengthened. Cooperation agreements can be reached with external parties in this area.

- Development of interception systems should be continued, including deployment of laser-based systems and their conversion into operational. At the same time, the Israeli public must be made aware that in the event of a high-intensity campaign on the northern front, the active defense system will not be able to provide a complete solution for missiles and rockets launched against Israel, and that efforts should therefore be directed to home front protection and public behavior. Readiness indices for force buildup in defense against high-trajectory weapons (inventories versus a reference scenario) should be devised.

Development of interception systems should be continued, including deployment of laser-based systems and their conversion into operational arrays. High-powered laser system developed in Israel

Photo: Minister of Defense, Spokesperson’s Unit

- The IDF’s missile capability and remote precision firepower should be improved, with tasks allocated and divided between firepower of this sort and airborne firepower.

- The cyber defense system for security computer infrastructure should be stepped up, and defense of critical infrastructure and civilian companies, which if damaged could impact negatively on the Israeli economy, should be supported. At the same time, the operational doctrine for the offensive cyber effort should be formalized, and a suitable force should be assembled at both the General Staff level and for supporting operations at the command and divisional level.

The General Staff and the Operations Level

In view of the necessary changes, the General Staff structure, size, command and control structure, and the link in wartime between the area commands and branches should be examined. The approach should emphasize decentralization, independence, and room for initiative at the operations level, as well the efficient use of the force in a scenario in which the IDF fights simultaneously on remote fronts that differ in nature.

Personnel

The IDF personnel model should be thoroughly overhauled, from recruitment to retirement and in all arrays: compulsory military service, the standing army, and the reserves. The principles of this necessary change resemble those described here for other aspects of force buildup: differentiation, efficiency, and adaptation to the needs and spirit of the time, while maintaining conscription and the model of the “people’s army.”

Budget, Legislation, and Oversight

A multi-year budget for the IDF should be approved. The defense spending framework should not be substantially changed, but its priorities should be altered – both between the various security bodies and within each of them.

Preparations should be completed for the budget change that will begin in 2025, when “conversions” of United States aid money are to be gradually eliminated, which will increase the burden on the shekel security budget by many billions.

The legislative processes pertaining to IDF recruitment, establishment of a civilian-security service, and the necessary changes in the personnel sphere should be completed.

Government oversight of the intelligence agencies by a special minister in the Prime Minister’s Office should be formalized. The prime minister, who is responsible for approving the use of military and clandestine force, currently conducts this oversight himself, but he is unable to closely supervise organizational and budgetary changes in these agencies.

Preparations for Possible Iranian and Regional Nuclearization

Under the auspices of the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Defense, preparations should be made for a scenario in which nuclear capability is acquired by Iran and other countries in the Middle East, while examining the policy options, a recommended operational concept, and the implications for force buildup. Such a situation is liable to require not only physical preparations involving a large investment in defense, but also to challenge fundamental assumptions about the behavior of Israel’s various enemies in a conflict, the stability of regimes in the region, and the very existence of deterrence in a nuclear era, which differs substantively from conventional deterrence.

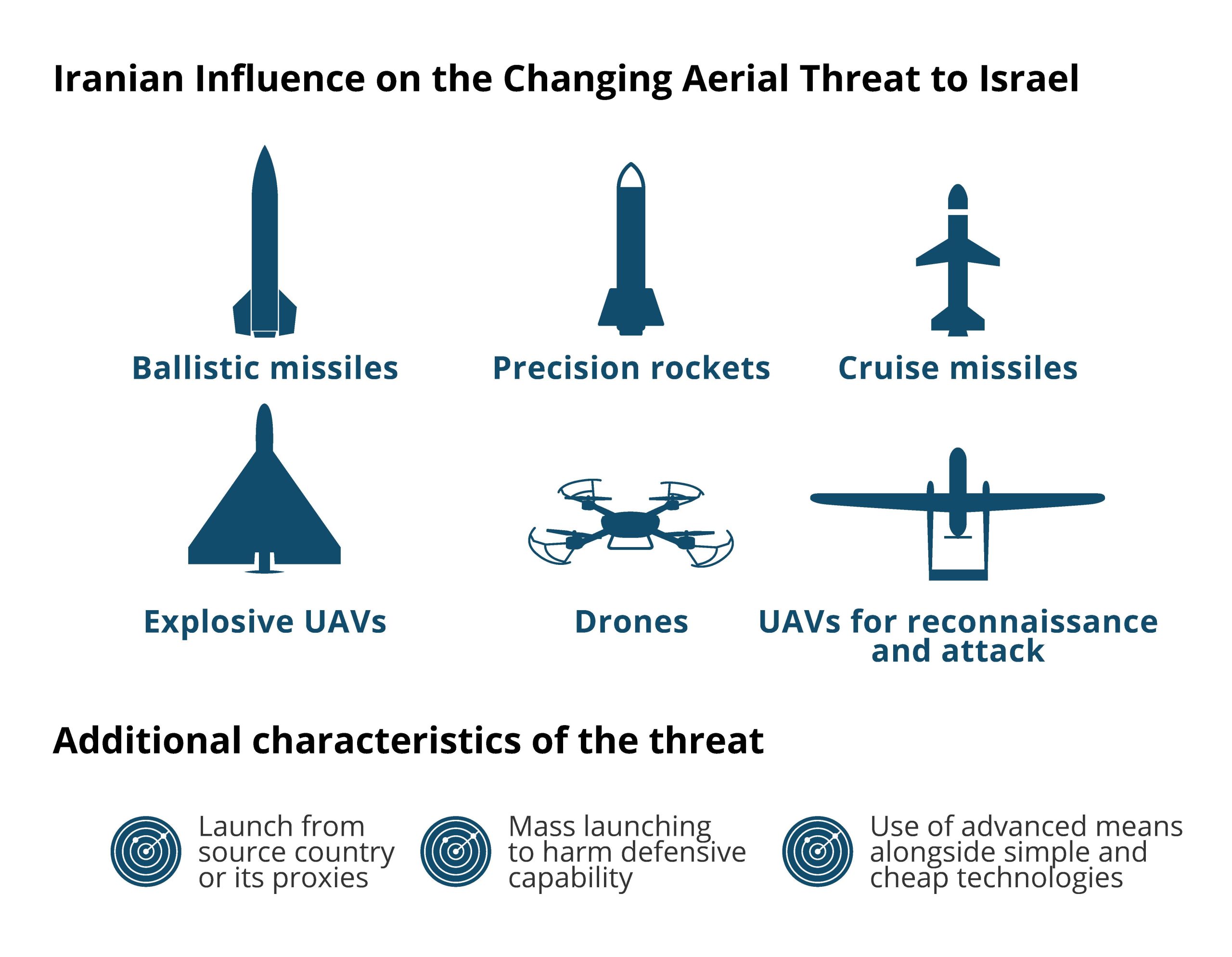

The UAV Threat

In the past year the military threat to Israel saw little change, and significantly, the Iron Dome system proved its effectiveness once again. During Operation Breaking Dawn (August 2022), more than 1,000 rockets were launched toward Israel over the course of two days and intercepted by Iron Dome with a success rate of 96 percent. However, this is not a definitive scenario regarding future challenges.

The war in Ukraine is an example of the future battlefield that Israel might experience, for example, in a war in the northern arena. In Ukraine, unmanned vehicles are used extensively, including many with a low level of precision, and have caused much collateral damage and harm to civilians. Some of the attacks on the Ukrainian home front were launched with kamikaze drones such as the Shahed 136, which are supplied to Russia by Iran. Iranian experts help Russia operate them, and Iran has also supplied knowledge and components that enable independent production, and apparently in return receives monetary payment as well as advanced Russian cyber capabilities.

In Ukraine, unmanned vehicles are used extensively. Building in Kyiv damaged by a suicide drone

Photo: Oleg Pereverzev/NurPhoto

In the past decade, drones, including various kinds of attack drones, which were exclusive weapons in the hands of a few countries, have become familiar weapons even in failed and rogue states and non-state organizations. More specifically, however, the events in Ukraine and violent conflict arenas in the Middle East showcase both the impact of different technologies – some of them cheap, off-the-shelf technologies that are available and simple to operate – and the nature of warfare itself. These technologies enable fast preparedness, knowledge transfer, and even the transfer of experts or operators to aid in the fighting. Iran is among the leaders in the export of such activities, which are called WAAS (warfighting as a service). The combination of off-the-shelf technologies and the overall expansion of the aerial threat to Israel could have strategic impact, given the interception capabilities that Israel has today, along with gaps in its home front defense capabilities.

In order to prepare for the changing aerial threat, including the drone threat, Israel must strengthen home front defense, expand defensive measures, and adjust doctrines on the use of force and defense among IDF forces, while preparing to sustain damage and undertake recovery efforts for critical infrastructure and the civilian home front. Even though this is not a completely new threat but rather an intensification and evolution of a seemingly familiar threat, the change is significant. Israel should learn from the war between Russia and Ukraine, due to the possibility of a conflict with Iranian involvement or influence, and trends that could characterize every future battlefield. Learning lessons in this context is also important given the upcoming publication of the IDF’s new multi-year plan with the entry of a new Chief of Staff, which will shape Israel’s military buildup in the coming years and bear much import for the coming decades.

One of Israel’s strengths is its defense industries. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted countries to consolidate independent defense capabilities and made 2022 one of the strongest years for Israeli defense exports. For example, Israel Aerospace Industries announced at the end of the third quarter of 2022 that it was the most profitable period in its history, with 12 percent growth in sales, to $3.601 million, and a 29 percent increase in gross profits, compared to the corresponding period in 2021. Other defense industries also closed major deals with countries around the globe, in a manner that again emphasizes the importance of the military-technological field for Israel economically and in terms of international influence.

Israel’s technological capabilities, and chiefly its defense technologies, prove repeatedly to be a diplomatic tool in foreign relations, because Israeli innovation is attractive in the eyes of many countries, including Morocco, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain. Technological collaboration, and not only the sale of weapons, enables the deepening of existing ties and the creation of new ties. In the upcoming year, with the ongoing campaign in Ukraine, the demand for Israeli military technologies could continue to intensify. Nevertheless, there are also potential risks, such as the risk of technology leakage and duplication or United States objections to certain deals. Consequently, Israel should continue to operate and advance Israeli technologies and exploit the opportunity to strengthen international ties through both civilian and defense exports, while paying attention to potential sensitivities in relations with the United States.