The Climate Crisis: A Challenge for International Solidarity

Shira Efron

Trends

Coming decade is critical for human security · Great power competition limits potential for cooperation · Disappointment with the Glasgow summit alongside important advances · Spotlight on the Middle East in 2022 · Israel joins climate struggle

The Climate Crisis: A Challenge for International Solidarity

Shira Efron

Recommendations

Translate words into action · Update emissions target for 2030 · Plan for implementing commitments by 2050 · Governmental preparedness plans · Use assets in water, food, and energy technologies and advance regional environmental cooperation

The year 2021, which began with the change of administration in Washington in January and ended soon after the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in November, was “the year of climate change” in the international arena. Despite disappointment over the failure of the conference to achieve its main objectives, the event did mark important achievements, including the return of the United States to global leadership, the formulation of several international treaties and agreements, and the enlistment of many countries, including Israel, to increase their commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, the great power competition, along with the reluctance of leading countries, especially China, Russia, and India, to set ambitious emission targets, undermined the US ability to spearhead significant change that would limit the average rise in temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, which is considered the upper limit for ensuring a relatively safe world for the future of humankind. In 2022 the international community will continue to focus on the climate crisis, and the UN conferences expected to be held in Egypt in 2022 and in the United Arab Emirates in 2023 will spotlight the Middle East and North Africa – a region that is especially vulnerable to climate change. Israel declared it is at the beginning of a climate revolution, and began taking important steps in this context. However, to cope with climate change, both in terms of risk preparedness as well as the ability to seize opportunities, the Israeli government must translate their rhetoric into action.

2021: ‘’The Year of the Climate Crisis”

The year 2021 will be remembered as “the year of the climate crisis.” While gradual climate change has been ongoing for decades, until now the issue never commanded the international stage. Two formative events – the start of the Biden presidency in January and the UN Climate Change Conference in November in Glasgow (COP26) – represent the issue’s unequivocal importance on the global stage and its implications for Israel.

President Biden advanced the climate crisis to the top of the United States national security agenda, and his first actions included returning to the Paris Agreement, after the withdrawal from the agreement by Donald Trump, who denies climate change; appointing former Secretary of State John Kerry as US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, while upgrading the position; appointing the former Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, Gina McCarthy, as head of the new White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy; signing a series of significant executive orders that aimed to cope with “the existential threat of climate change”; and pledging to reduce carbon emissions and invest $500 billion in clean energy and climate justice. All federal government agencies increased their engagement with climate change, including the Pentagon, which has in fact dealt with the climate crisis for almost two decades; increased efforts include a designated Assistant Secretary of Defense for the issue, and new reports analyzing risk and military preparedness for coping with climate change. The American focus, coupled with the Biden administration’s efforts to restore relations with partners and allies and return to global leadership, have made the climate issue a central one on the international agenda

Failure to ensure commitments that would limit global warming significantly. Demonstration during the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow

Photo: REUTERS/Dylan Martinez

The preparations for COP26, which followed an especially hot summer with heat waves, numerous severe wildfires, storms, floods, and other extreme weather events, led many countries, including Israel, to further engage with climate change. In the days leading up to the conference, some 150 countries submitted or renewed their national plans for addressing the crisis, and despite COVID-19 limitations, a record number of participants and leaders were present at the conference itself.

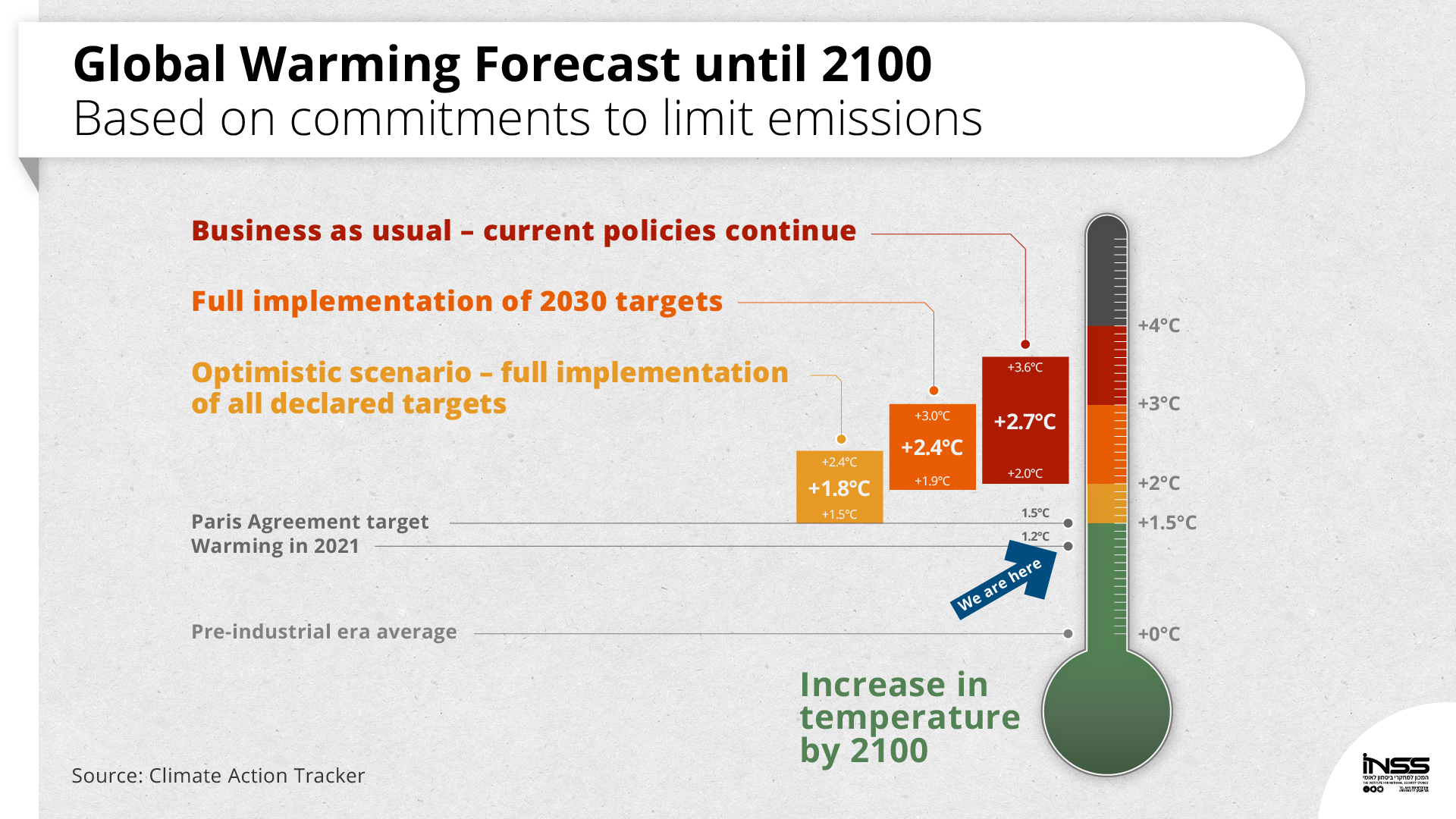

The British hosts hoped that participants would make international commitments that would limit average global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels – a rise that is considered the upper limit for securing a relatively safe world for humankind, ameliorating climate phenomena, and preventing the collapse of global systems. However, the conference failed to achieve this target. Although many countries committed to 2030 emission targets corresponding to the goal of 1.5 degrees, including the United States, the European Union, the UK, Japan, Canada, and South Korea, implementing these commitments will only moderate the expected rise in average temperature – from 2.7 degrees Celsius in the business-as-usual scenario to 2.4 degrees. The lack of a Chinese commitment to more ambitious goals than those that Beijing presented in Paris in 2015 is especially concerning, as China is responsible for about 27 percent of global carbon emissions (more than all developing countries combined). In addition, the lack of cooperation from China lent legitimacy to other countries, such as India, to lag behind.

At the same time, the conference saw significant achievements. Beyond the momentum and renewed American leadership, the conference led to important agreements (signed by over 100 countries) to reduce methane emissions and stop deforestation, and to an international agreement on preserving ecosystems in 30 percent of territory by 2030; a commitment by more than 25 countries to end investment in fossil-fuels; an agreement on reducing coal use; the formulation of rules for an international mechanism on carbon pricing; a demand to improve the 2030 targets; and changing the mechanism for tracking and reporting progress on implementation of international targets from every five years, as originally planned in Paris in 2015, to an annual basis, in part by holding another conference in one year in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. In addition, despite the rising competition between the great powers, which limited significant American-Chinese cooperation on the issue, the conference concluded with a joint declaration by John Kerry and his Chinese counterpart, Xie Zhenhua, that the United States and China, the biggest emitters, would work together to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions over the current decade.

2022: Critical to Maintaining Momentum

The year 2022 will likely be marked by continuity from the past year and by major efforts on the part of the United States, the UK, and other European countries to keep climate change as a top global priority. Thus, the forthcoming Sharm el-Sheikh conference will function in effect as the second part of the Glasgow conference, providing a second chance for countries to increase their commitments to reduce emissions. If this conference does not achieve its goals, the momentum will likely be lost, along with the chance of securing a rise of only 1.5 degrees. One of the keys to success is China. On the one hand, the joint declaration in Glasgow and the assumption that China will not want to be seen as a country that might endanger the future of humanity are reasons for optimism. On the other hand, the intensifying competition, on the verge of rivalry, between the United States and China could prevent their cooperation, which is essential for addressing the climate crisis. The second key to success is economic assistance to developing countries for building green economies that are suited for a new world. Donor countries did not meet their Paris commitments, whereby they would provide $100 billion of aid per year to the developing countries. Instead, this target is expected to be implemented only in 2023. However, the funding levels are much higher and depend on massive private investment, philanthropy, loan mechanisms, and risk reduction instruments, along with regulation and economic development measures that will be required on the part of developing countries themselves – measures that will be difficult to carry out in the short term. Meanwhile, Biden’s staggering efforts to pass his ambitious Build Back Better bill, which includes a plan for investment in domestic green energy will also affect whether the momentum is maintained, as well as US credibility and its ability to lead the international community on this issue.

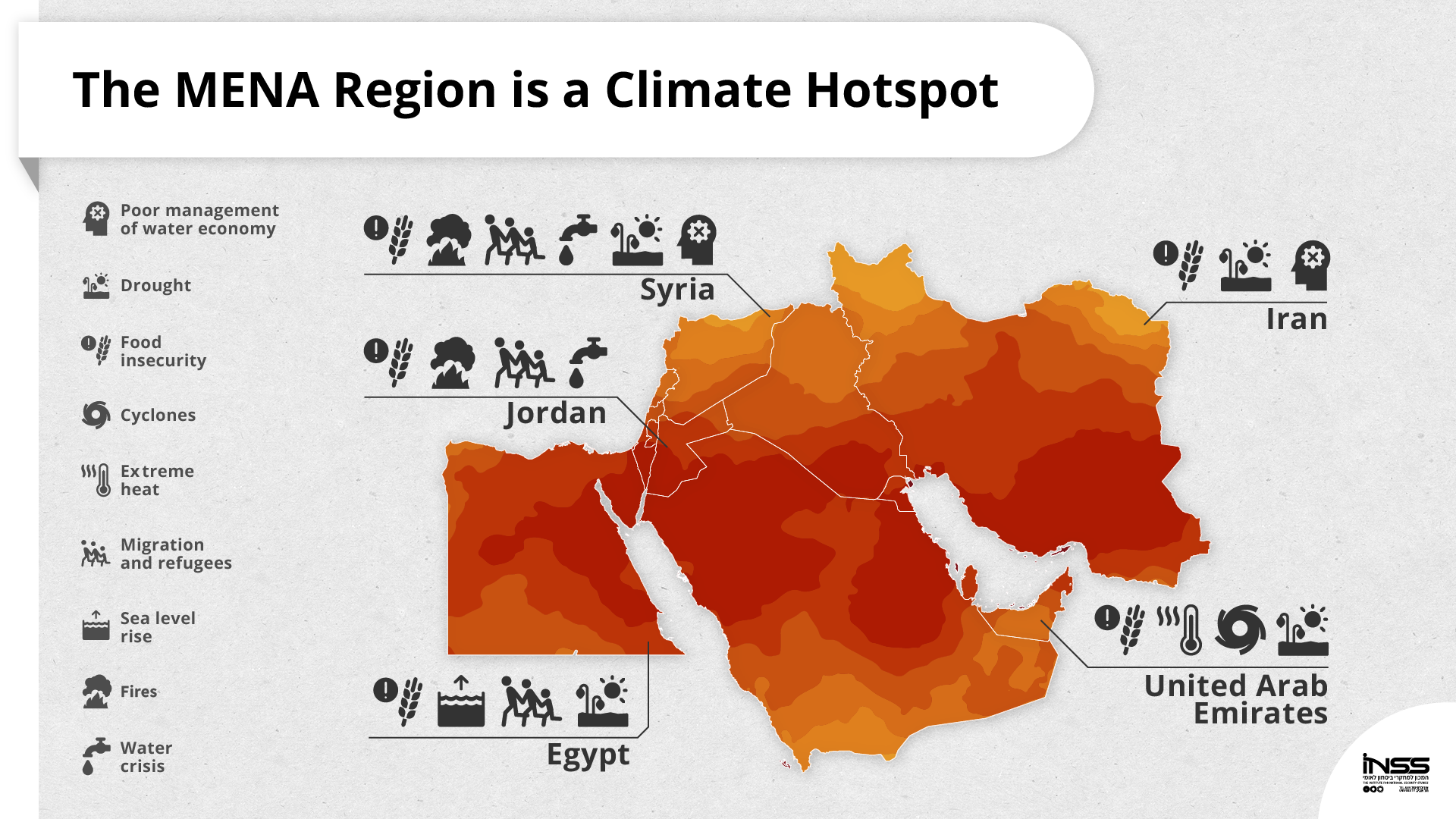

The choice of Egypt as the host of the next UN conference and the United Arab Emirates of the one thereafter will shift the spotlight to the Middle East and North Africa, one of the world’s most vulnerable regions to climate change, including temperature rises, food and water shortages, sea level rise, and an increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. These changes could further upset regional stability, which is already undermined, lead to mass waves of migration, and create even more favorable conditions for the growth of terrorist organizations. Alongside the challenges, the climate prism has the ability to advance important regional partnerships in the areas of renewable energy, water, and food security, such as the declaration of intent signed by Israel, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates in late November on regional cooperation in the struggle against the climate crisis, through the construction of solar energy and desalination facilities.

Implications and Policy Recommendations for Israel

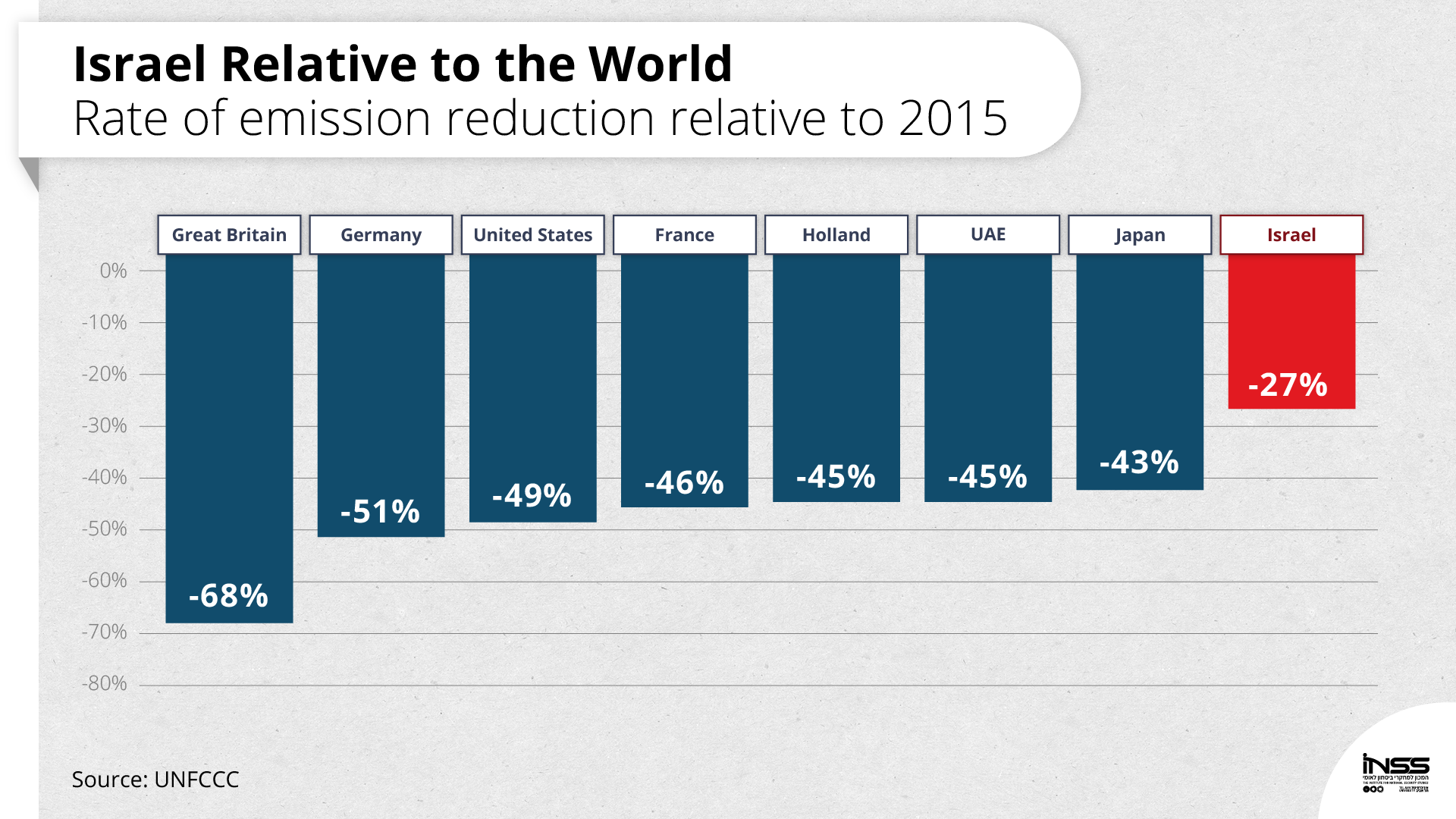

Although Israel joined the Paris Agreement in 2016, has advanced certain measures to adapt the civilian market to the climate crisis, and passed government resolutions on the issue, in practice Israel’s climate policy until the fall of 2021 can be seen mainly as lip service. As documented in the last State Comptroller’s Report, 84 percent of the public bodies that the Comptroller checked do not have any plan for coping with the climate crisis. The report also stated that out of 278 tasks included in the government decision on adaptation for climate change, only 16 percent appeared in ministerial work plans, and only four designated civil servants (out of 83,000) dealt regularly with climate change. Despite its small size, Israel emits an amount of greenhouse gases similar to a medium-sized country. In addition, Israel did not meet the targets that it set as part of the Paris Agreement, and according to the Comptroller, “progress in achieving all the sectoral targets ranges from lagging to zero.”

However, in advance of Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s meeting with President Biden in August and later ahead of COP26, the Israeli government has changed course. It significantly increased Israel’s commitments (zero carbon emissions by 2050, ending the use of coal by 2025); joined international agreements on forests and methane emissions; announced that the impacts of the climate crisis will become part of the National Security Council’s annual assessment; and approved a plan to accelerate infrastructure projects to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The government also approved a plan to support climate innovation and established a climate innovation and technology committee within the Prime Minister’s office. President Isaac Herzog has sponsored a climate forum, and the IDF has also begun dealing seriously with the issue. These are important and welcome steps, and the Prime Minister was right when he said in Glasgow that “we’re currently doing more to promote clean energy and reduce greenhouse gases, than at any other time in our country’s history.” However, considering the low bar set by Israel’s policy so far, this is insufficient. If the government is indeed serious about beginning a climate revolution, rhetoric must be backed by action, and without delay.

Israeli policy on climate change: words must be translated into action. Fire at Haifa oil refinery, December 2016

Photo: REUTERS/Baz Ratner

The Climate Law has yet to be approved, even though it was part of the coalition agreement, and neither has a climate emergency been declared. The welcome commitment to end emissions by 2050 is not backed up by a detailed and budgeted action plan. Israel’s 2030 commitment target of reducing emissions by 27 percent has not been updated and is considered especially low. The 100 point plan that the Prime Minister announced includes old plans that were already declared and even budgeted, but without metrics, targets, and timelines. Government ministries that were supposed to develop adaptation plans in their areas of responsibility have not yet done so, or are only at the beginning of the process. The Inter-ministerial Administration for Climate Change Adaptation operates without authority, budget, or designated manpower. Even though Israel previously announced that it would establish a ministerial scientific advisory committee, a science and knowledge center for risk assessment, and a national computation center for climate simulations at the Israel Meteorological Service, these promises have neither been fulfilled nor budgeted thus far.

In 2022, Israel’s government must ensure the implementation of existing decisions, pass the Climate Law, and enlist the various government ministries in putting together significant climate adaptation plans . The local government level should also be enlisted via these plans, as it is essential for implementing the adaptation effort. Likewise, the Knesset should ensure that government decisions are implemented and back them up with additional legislation as needed.

Considering the impacts of the climate on geopolitical stability in the Middle East and its implications for force buildup and operation (for example, equipment, infrastructure, and the fitness and health of military and security personnel), the security establishment should work quickly and thoroughly to adapt action plans, budgets, and acquisition guidelines to a climate reference scenario, while maintaining ongoing communication between the heads of the security establishment and climate experts. As part of the national effort, the defense echelon should also work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and pollution. The National Security Council’s plan for treating the climate crisis as one of the key five issues on the national security agenda should be backed up with actions and dedicated personnel. In November 2021, for the first time, the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee held a hearing on adaptation of the defense echelon to the climate crisis as part of Environment Day, but such discussions, including in the subcommittees, must become routine, as is the case in the US Congress and in the parliaments of many other countries.

Notwithstanding challenges, the climate crisis creates important opportunities for Israel. Israel is a major potential asset in terms of water and food technologies, and innovation in general. The Prime Minister was right in saying in Glasgow that Israel’s impact on climate change could be great despite its small size. This potential, along with access to investment funds and markets in Europe, the United States, and Asia, can position Israel as a global leader in the fight against climate change. The Abraham Accords and the venues chosen for the next two UN climate conferences in the Middle East can help deepen existing collaboration and lead to additional partnerships in this field, and position Israel as a positive force in the region.

However, developments in the fields of energy and other climate technologies require infrastructure, a knowledge base, and creation of an innovation ecosystem, all of which are not possible without significant government support. Along with governmental plans and the climate innovation committee at the Prime Minister’s Office, Israel should pursue a similar path as it did in 2010 on the cyber issue, and establish a special team to develop a comprehensive national plan encompassing both the civilian and military sectors, including significant investment in research, to position Israel among the five leading countries in the field of climate technologies. The successful work in the cybernetic field, which continues to bear fruit to this day, serves as a model for the preparation necessary for implementing the climate revolution – both in Israel’s domestic policy and in its foreign policy.