The Northern Arena: Proactivity in Order to Weaken the Iranian-Shiite Axis

Udi Dekel, Carmit Valensi, and Orna Mizrahi

Snapshot

Iranian entrenchment in Syria · Collapse of Lebanon, with ongoing Hezbollah military buildup, including precision missile project · Potential escalation to a “northern war,” despite deterrence and the desire to avoid it

The Northern Arena: Proactivity in Order to Weaken the Iranian-Shiite Axis

Udi Dekel, Carmit Valensi, and Orna Mizrahi

Recommendations

Prepare for “northern war” as the primary military threat, while pursuing political and security efforts to prevent it · Adjust public expectations as to the costs of the war to the home front · Continue “campaign between wars”

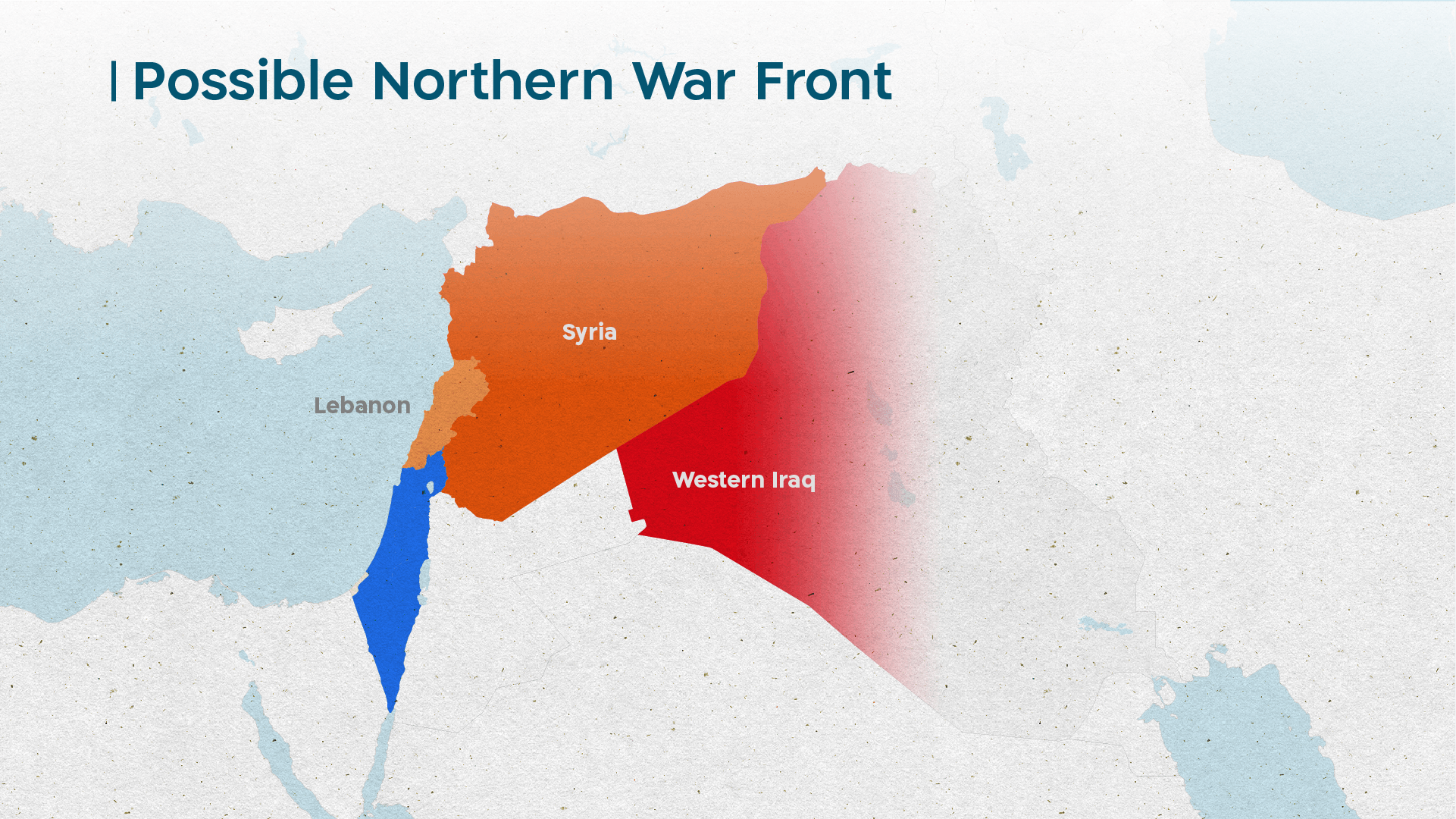

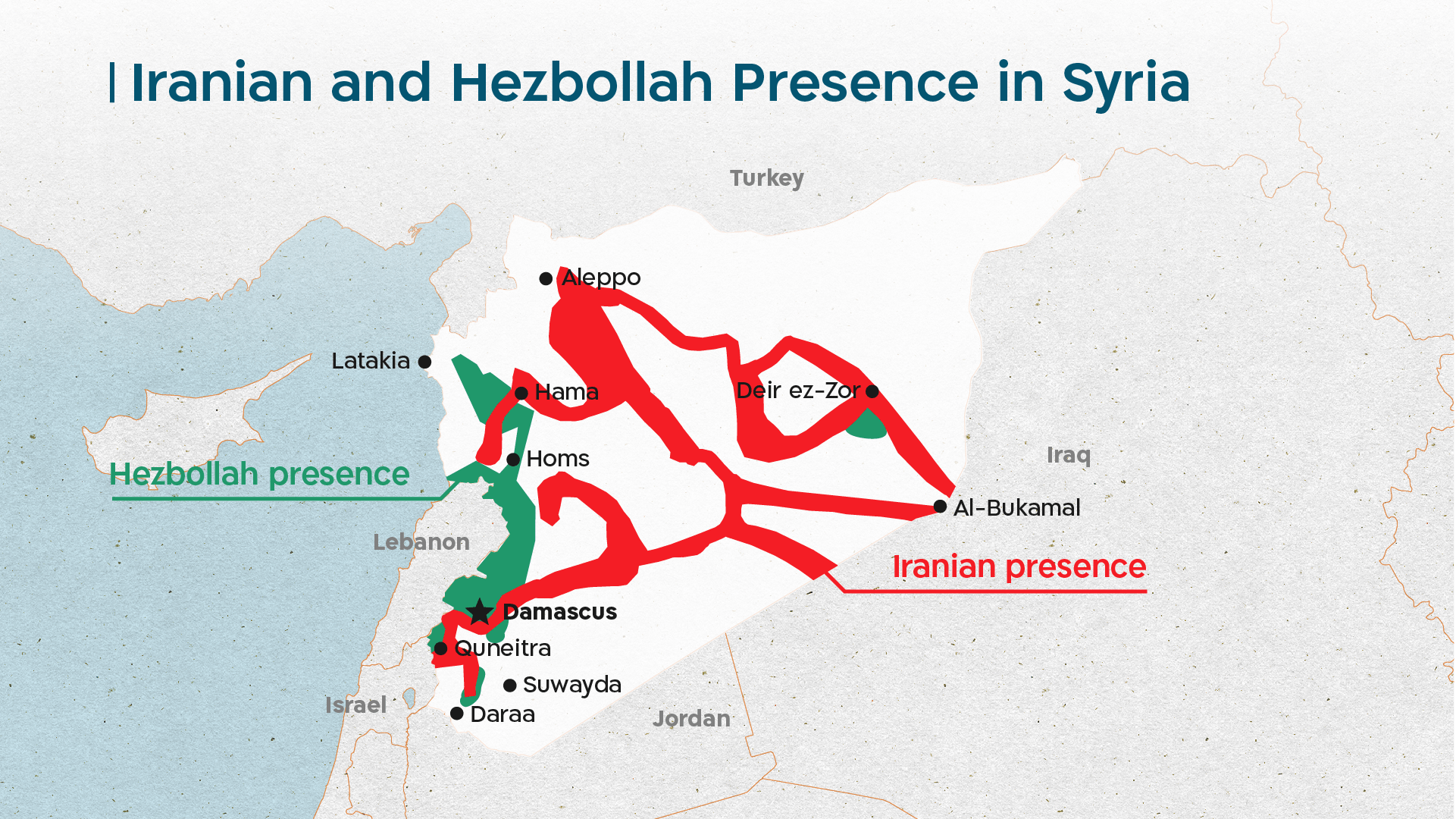

The main challenge for Israel in the northern arena is the entrenchment of the Iranian-Shiite axis and the buildup of the Iranian “war machine” in Syria and Lebanon. This entrenchment has lagged in relation to Iran’s vision and original plan, due to the Israeli “campaign between wars”; the killing of Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani; the US “maximum pressure” policy; the economic, political, governance, and healthcare crisis in Lebanon, which also affects Hezbollah; and Iran’s grappling with the COVID-19 crisis. Israel should continue the campaign between wars with determination – to erode and slow Iran’s consolidation and that of its proxies, and to focus on disrupting the precision missile project while adapting the methods and rate of operation to the arena’s changing conditions. The challenges in the northern arena will not disappear, even though the parties do not want a large-scale escalation. A high level of readiness is necessary due to the risks of an unplanned escalation dynamic that could lead to a war in the northern arena, including Lebanon, Syria and western Iraq.

The Iranian-Shiite Axis under Pressure

The consolidation of the Iranian-Shiite “war machine” in the northern arena is the most severe conventional threat to Israel’s security. To be sure, Iran is weathering one of its worst periods ever under the regime of the ayatollahs; this in turn impedes the military buildup of the axis it leads, which includes Hezbollah and the Assad regime. Buildup of the war machine intended for attack on Israel’s northern arena continues, however, including equipment with rockets, missiles (with improved precision), and offensive unmanned aerial vehicles; development of offensive and defensive cyber capabilities; training of terror squads for terrorist attacks in the Golan Heights; and training of land forces to infiltrate into Israel from Lebanon. At the same time, given the challenges and constraints facing the axis coalition, Iran does not want a war with Israel at the current time and under the current conditions. Despite its commitment to avenge the killing of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, father of the Iranian nuclear program, Iran is therefore carefully weighing its steps – at least until the ramifications of the end of the Trump era and Biden’s entry into the White House are clear.

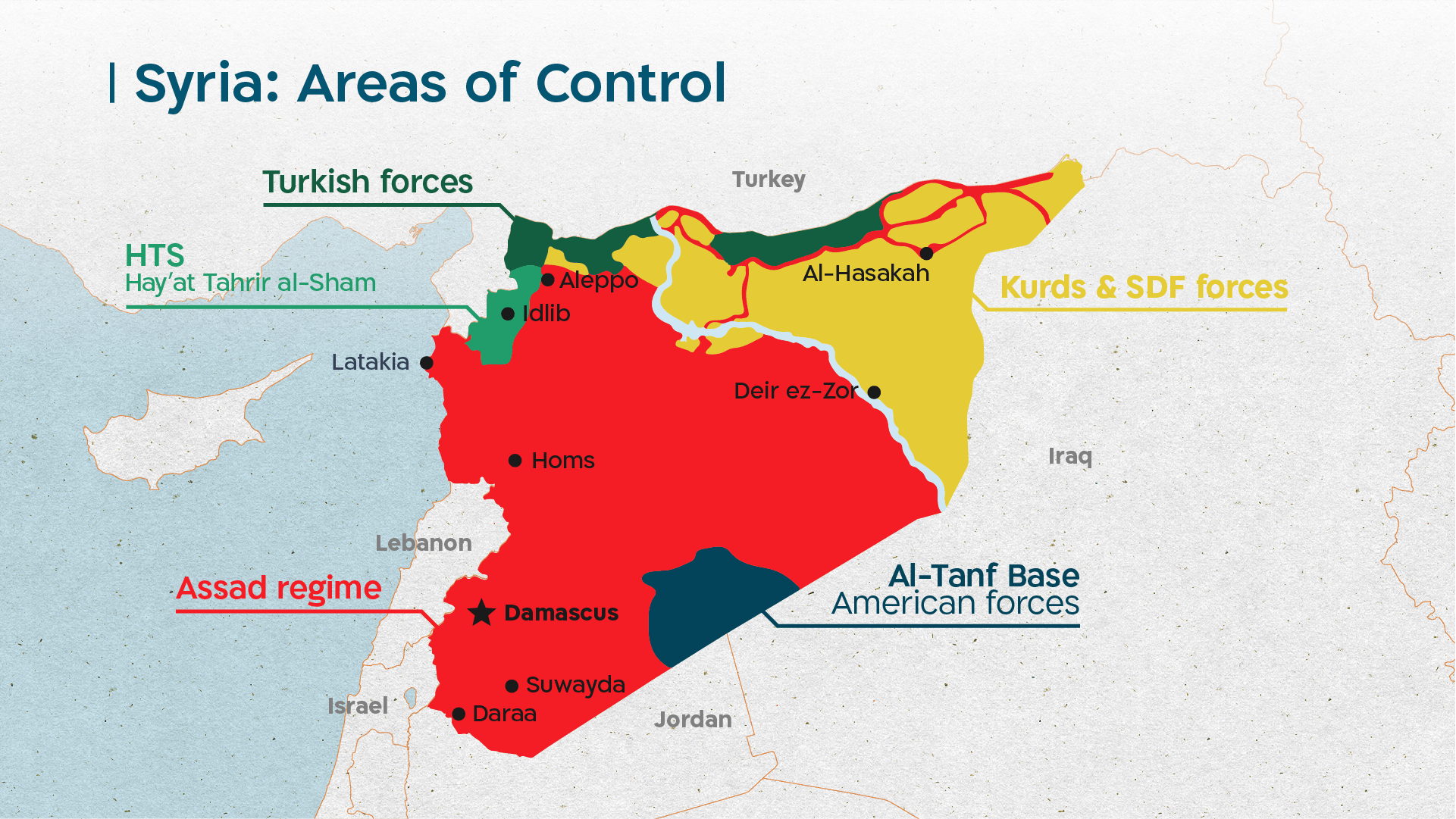

In Syria, the Assad regime is hard pressed to regain control over all parts of its former territory and restore Syria to a sovereign and functional country. The map showing who controls which areas in Syria has remained frozen as a result of the large number of elements present: Turkey, US forces, internal opposition groups, Kurds, tribal groups, and ISIS. In addition, there are difficulties in governance and a diminishing commitment among the pro-Assad coalition – Russia and Iran – to continue fighting on behalf of the Syrian regime. At the same time, the regime’s actions have become even more dictatorial and violent. The population in Syria will therefore continue to suffer from rifts and rivalries, and most of the Syrian refugees will not return to their homes and their country. The economic crisis in Syria has deepened, with shortages of bread, fuel, and other basic commodities. Poverty and hunger have become ubiquitous, inflation has skyrocketed, infrastructure has been destroyed, and the COVID-19 pandemic has compounded all these woes. It is generally believed that Syria’s reconstruction will take many years and require some $300 billion in aid.

This reality has amplified Syria’s dependence on external support, primarily Russia and Iran. Russia wants to institute political reforms in Syria, provided that the current regime is preserved, in order to convert its military success in the Syrian civil war into a political achievement and prolong its influence in the country and the entire region. Moscow believes that there is no strong figure in Syria that can replace Assad as president, despite his limitations and drawbacks. At the same time, the military-defense agreement between Syria and Iran signed in July 2020 indicates that President Assad is avoiding exclusive dependence on Russia, and wants to strengthen his military alliance with Iran. Assad, with Iranian support, is doing whatever he can do to torpedo the process of political reforms, for fear of eroding his powers and even losing his throne. The clashing interests of Russia and Iran, manifested in competition for increased influence in Syria, and especially Assad’s maneuvering between them, make it difficult to put Syria on the road to governmental reforms and reconstruction.

The consolidation of the Iranian-Shiite “war machine” in the northern arena is the most severe conventional military threat. Military parade in Tehran

Photo: REUTERS/Stringer

Although Moscow endeavors to keep its promise to the United States and Israel to maintain Iran’s presence and influence outside of southern Syria at a distance of 80 kilometers from the border with Israel, Iran has steadily tightened its grip on the area, with an effort to entrench its proxies close to the border in the Golan Heights, in order to form another front against Israel. Iran is relying mainly on Hezbollah; Syrian army units subject to its influence (among them the 4th division under the command of Maher al-Assad); recruitment of local Syrian groups and individuals in local defense militias founded, trained, and armed by Iran; and internal security agencies.

The story of the political efforts to find a political solution for the situation in Syria – the Astana and Geneva processes – demonstrates that in the Syrian theater, facts are first established on the ground, and thus the foundations for the future of Syria are determined by a division of influence between the actors involved, not by international peace processes. Assad has no desire to decentralize political power or to promote political reforms, as demanded by the Geneva process. In his view, the Syrian opposition groups are nothing more than representatives of terrorist groups operated by Western countries opposed to continuation of his rule, and his unwillingness to compromise with them has thus far served him well.

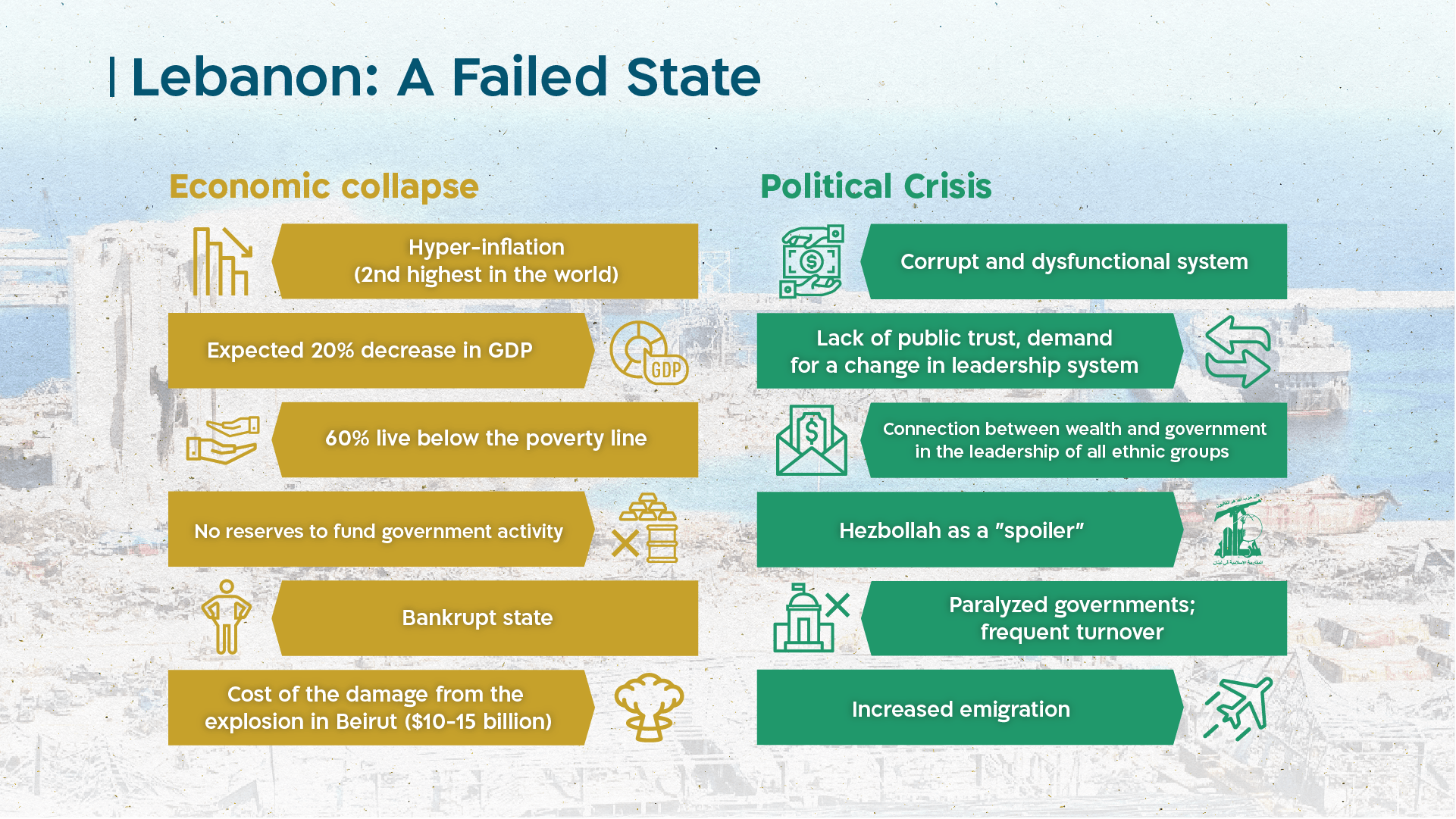

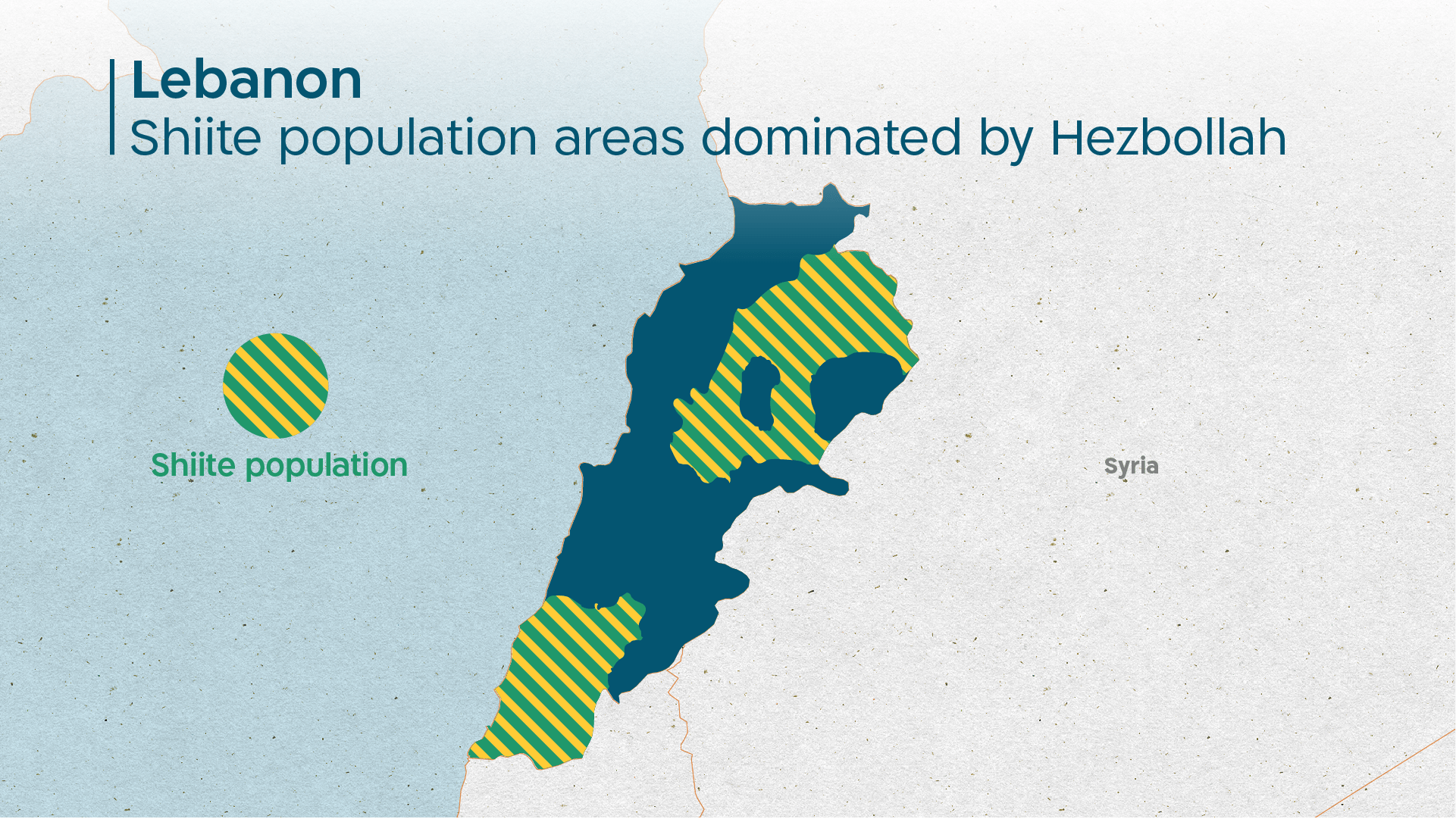

Lebanon is mired in a three-pronged crisis: economic collapse (hyper-inflation, bankruptcy, poverty, unemployment, negative growth, emigration); loss of governance (paralysis in the political system, corruption, ongoing demonstrations); and a healthcare crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The United States continues to maintain a military presence in Iraq and eastern Syria, albeit limited, for the purpose of preventing a resurgence of the Islamic State and Salafi-jihadist groups. At the same time, the US is striving to restrict Iranian influence in the region by thwarting the Iranian-Shiite axis land bridge between Iraq and Syria, and from there to Lebanon. In addition, the presence of US forces facilitates the continued Kurdish autonomy and the functioning of the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their control over natural resources in eastern Syria.

Turkey, preparing for a prolonged stay in northern Syria, seeks to prevent both territorial continuity under the control of the Assad regime and independent rule of the Kurdish cantons in northern and northeastern Syria. As part of this effort, Turkey is trying to turn the areas under its control in Syria into military, economic (including use of Turkish currency), social, and cultural (study of the Turkish language, for example) protectorate territories. President Erdogan is still striving to create infrastructure for settling Sunni refugees in the Kurdish strip under its control, due to the heavy burden for Turkey created by the presence of 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Turkish territory. For Turkey, Syria also constitutes a site for the recruitment of mercenaries from the ranks of the Syrian rebels for military service in areas extending from Libya to the Caucasus. The fighting in the Idlib district highlighted the stark clash of interests in Syria between Russia and Turkey, and on the other hand, their mutual interest in avoiding a direct clash between them.

Syria’s infrastructures are ruined, and Syria’s reconstruction will take many years and require hundreds of billions of dollars. Overlooking ruins in Idlib, February 2020

Photo: REUTERS/Umit Bektas

Shifting Tides

Iran has found it difficult to synchronize between its theaters of influence – Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon – in the framework of the Shiite axis, despite its determination to continue building military, political, economic, and social infrastructure to safeguard its influence in these areas in the long term.

- In Syria, Iranian entrenchment has been slowed by the killing of Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani, Israel’s campaign between wars, and the United States policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran, in addition to the challenges facing Iran in its internal theater. The result has been a downsizing of the Iranian forces in the field and a modus operandi that relies more on local groups. At the same time, economic problems have led Iran to put greater emphasis on civilian consolidation (religion, education, control of land), and increase its efforts in operating drug smuggling networks in order to expand its influence through financing, given its extensive financial difficulties.

- Elements in the Assad regime that formerly regarded Iran as an asset now perceive it as a liability. This is true even more so from Russia’s standpoint, because Iran is hampering efforts to stabilize Syria, implement reforms, and open the door to international aid. The competition between Iran and Russia over influence in Syria has recently focused on the southern part of the country. Each of them is organizing local forces loyal to it, and a struggle is underway between them for control of the Quneitra, Daraa, and Suwayda provinces.

- The appointment of Mustafa al-Kadhimi as Prime Minister of Iraq in April 2020 has created potential for a change in the balance of power between the government and the Popular Mobilization Forces, supported by Iran. This development could have a negative impact on Iran’s grip on the country.

- The collapse of Lebanon: Internal and external distress is causing problems for Hezbollah, which is battling to preserve its leading status, influence on decision makers, military power, and freedom of action. Its ability to serve Iranian interests is therefore likely to diminish.

- A new regional axis is forming as a result of accelerated normalization between Israel and pragmatic Arab countries, together with Jordan and Egypt. This axis is emerging as both an anchor of stability and a barrier against the spread of the Iranian-Shiite and Turkish-Qatari axes. The potential change in the regional atmosphere joins Lebanon’s agreement, following a decade of steadfast refusals, to hold talks with Israel on delineating the maritime border between them.

The change of the US attitude toward Iran under the Biden administration – with an easing of both the sanctions and the “maximum pressure” – is likely, together with willingness to return to the nuclear agreement. A moderate attitude will enable Iran to resume its destabilizing activity in the region, invest in strengthening the Shiite axis, step up its consolidation in Syria, and recruit and utilize Syrian combat forces to intensify friction on the Golan Heights border. This will offset the advantages of “maximum pressure” in thwarting consolidation of the Iranian axis.

Three trends are emerging in Lebanon. The first is ongoing collapse, loss of governance, and economic bankruptcy, with no solution on the horizon. The second is mounting international pressure on Hezbollah and internal criticism of the organization, which from Hezbollah’s perspective increases the tension between Lebanon’s national interests and Hezbollah’s sectoral interests and commitment to the Shiite axis, and magnifies Hezbollah’s dilemmas concerning an active conflict with Israel. The third is the enlistment of the international community, especially the West, in the effort to aid Lebanon, which is still contingent on the advancement of governmental reforms and the fight against corruption. This will indirectly have a negative impact on Hezbollah. The organization, despite its distress, will not lightly forego its dominant position in the Lebanese order, and can be expected to take action to hamstring political and economic reforms that weaken its status. Hezbollah will make it hard for Lebanon to obtain international economic aid, and is also likely to strive to prevent the achievement of understandings in the negotiations with Israel on the maritime border and the broadening of these contacts to include discussion of other issues.

Possible Changes in 2021

The battle over influence in Syria between Moscow and Tehran may move toward a collision: Russia is interested in stabilizing Syria and turning it into a functional tool, in part by increasing its role in the reconstitution of the Syrian army and the inclusion of rebel and Kurdish groups. For its part, Iran wants to turn Syria into a proxy through deep and multifaceted penetration of Syrian security, economic, educational, social, cultural, and religious institutions, while at the same gaining control over critical infrastructure, supporting pro-Iranian militias, and being involved in building the army and ideological and demographic change. These Iranian goals, especially those that weaken Russian dominance in Syria, are interpreted in Moscow as destabilizing factors.

The removal of Assad from the Syrian throne: As long as Assad stands at the head of the Syrian regime, Syria cannot progress toward stability as a functioning and egalitarian country in which all ethnic groups and tribes coexist on an equal footing. In order to upset the situation, liberate Syria from the Shiite axis and Iranian grip, and position the country on the path to stability and recovery, there is no avoiding the need to rid Syria of Assad’s leadership. It is recommended for Israel to abandon the idea that “better the devil you know,” who opened the door to Iran and the slaughter in Syria, “than the devil you don’t know.” Instead, Israel should support Assad’s removal, preferably in coordination with Russia and with the support of the United States. This will require a quid pro quo for Russia, in the form of an easing of the international sanctions against it, despite the difficulty resulting from mutual distrust.

Hezbollah has two options for generating change in Lebanon. One is a military takeover of the country in order to preserve its leading status. The second is escalating the military friction along the borders with Israel in Syria and/or Lebanon, in part for the purpose of diverting attention from distress at home, and maintaining the deterrence equation with Israel in Lebanon and extending it to the Syrian theater, in the service of the Shiite axis, in order to create another front against Israel. At this stage, it appears that Hezbollah has chosen a third option: “strategic patience” – refraining from hasty steps and focusing on enhancing its influence over the Lebanese establishment, while preserving its power and military independence in Lebanon and Syria.

As for Lebanon itself, there are two possible changes. The first is success in the effort by Western countries to promote a process of gradual reform as a condition for the provision of guaranteed aid. The second is negative – a worsening of the internal situation and an increase in internal political friction, culminating in chaos and/or the outbreak of another civil war.

Withdrawal of United States forces from Iraq and eastern Syria: The Trump administration portrayed the freeze of the situation in Syria as an achievement, including the inability of the Assad regime and its supporters to gain control over all areas of the country, the stalwart stand of the Kurds and their control of northeastern Syria and the country’s energy resources, and the Turkish presence on Syrian territory as a counterweight to Russian and Iranian influence in the country. The United States, however, is searching for a propitious moment to further reduce its involvement in the region. Withdrawal of its forces from Iraq and Syria will generate new trends, mostly negative for Israel, such as a stronger Iranian grip in the region and fortification of the land bridge from Iraq to Syria. On the other hand, it is possible that an American withdrawal will lead to increased competition between Russia and Iran over control of energy resources in Deir ez-Zor.

Success in Western efforts to promote reforms or a worsening of the internal situation to the point of chaos. Protester in Lebanon after the blast at the Beirut port

Photo: REUTERS/Mohamed Azakir

For Russia and the United States, Syria can be an area of cooperation. Syria is a theater of international crisis that includes both Russian and US military forces. The two countries have created an effective mechanism for preventing friction between them. Indeed, Syria is the only theater in which President Vladimir Putin and President Joe Biden are likely to achieve political agreement based on common interests – reducing Iranian influence in Syria – toward stabilization of the country on the basis of governmental, civil, and economic reforms. Moscow is hinting that it will be receptive to a deal with Washington if it includes agreement on Assad’s right to run in presidential elections, while implementing reforms that include the opposition in the governmental bodies, as well as economic benefits for Russia in the process of reconstruction in Syria.

Dissolution of Syria as a country: In effect, Syria has been split into a number of distinct regions. The Assad regime controls about 60 percent of Syria’s territory – the country’s backbone extending from Aleppo to Damascus. In the rest of the country, the rebels and jihadist groups under Turkish protection control the Idlib area. Turkey, which aims to achieve dominance in the northern part of the country and prevent the consolidation of Kurdish autonomy, controls a strip in northern Syria next to its border. The Kurds are maintaining their autonomy in northeastern Syria. In southern Syria, there are enclaves controlled by Assad’s forces, local forces under Russian protection, militias subject to Iranian influence, opponents of the regime, and Druze. This situation is likely to gain permanence with time, thereby denying the vision of a united Syria within the country’s borders. Continued economic decline and an absence of external aid are also liable to cause the collapse of the Syrian state.

Policy Recommendations

Israel has four strategic options:

- Continuation of the current policy: Adapting and adjusting to changes in the situation – continuation of the ongoing open and overt campaign between wars below the threshold of war, aimed at disrupting and reducing the military buildup of Iran and its proxies on the northern front. This includes maintaining military freedom of action on the northern arena and utilizing assistance from Russia in pushing Iranian military consolidation away from Israel’s border, currently with an emphasis on southern Syria, coupled with an effort, via Moscow, to influence any future arrangement in Syria. It also involves continued close coordination with the United States.

- A proactive policy to expel Iran and Hezbollah from Syria, which can also lead to the removal of Assad from office, while taking advantage of the weakness of the Iranian-Shiite axis and continuing strategic coordination with Russia and the United States. This requires Israeli intervention in southern Syria to strengthen local forces, and the formation of relations with local population groups opposed to the regime with humanitarian aid – food, fuel, and medical support – in order to create islands of Israeli influence that will carry weight in southern Syria and thwart the expansion of Iranian consolidation there.

- Pursuit of the potential of the political channel – primarily with Lebanon, and as a follow-up to the negotiations on the maritime border – to formulate and offer political and economic rewards for implementing a political process and connecting Lebanon to the axis of pragmatic and responsible Arab countries.

- A change in the approach of force operation: In Lebanon – attacking targets in the precision missiles project, coupled with willingness to risk escalation with Hezbollah, and taking advantage of the organization’s military and political weakness, a development that could possibly advance options for putting Lebanon on the path to recovery, with Western and Arab support. In Syria: stepping up attacks on Iranian targets, including targets of the regime, before Iran gains renewed confidence from the changed American attitude with Biden in the White House.