Strategic Alternatives for the Gaza Strip

Ofer Guterman

Executive Summary

After approximately a year and a half of war in the Gaza Strip, Israel stands at a crossroads and must formulate a relevant strategy regarding the future of the Strip. It faces a rather grim range of alternatives, all problematic in their implications and feasibility: encouraging “voluntary emigration”—an option whose strategic consequences have not been thoroughly examined in Israel and whose feasibility is low; occupying the Strip and imposing prolonged military rule—while this may severely weaken Hamas, it does not guarantee its eradication, and comes with the risk of endangering the Israeli hostages held by Hamas and incurring other significant long-term costs to Israel; establishing a moderate Palestinian governance in the Strip with international and Arab support—an option whose costs to Israel are low, but currently lacks an effective mechanism for demilitarizing the Strip and dismantling Hamas’s military capabilities; and finally, the possibility that political and military stabilization initiatives will fail, leaving Hamas in power.

The underlying assumption in analyzing these alternatives is that the return of the hostages is a higher priority than the collapse of Hamas’s rule in the Strip. For the purpose of professional analysis, the outline for releasing the hostages has been removed from the various alternatives for Gaza, with the hope it will be pursued regardless of which alternative is chosen.

The main tension arising from the analysis Lies in the desire to ensure the collapse of Hamas rule and dismantle its military wing, versus the heavy implications for Israel of occupying and maintaining control over the Strip for an extended period. Simultaneously, it appears that the new foreign policy directions of the Trump administration is also influencing the management of the crisis in Gaza, thereby narrowing Israel’s political maneuvering space and increasing its dependence on the interests and dictates of the US administration. Additionally, while the administration seems to be committed to neutralizing the military threat posed by Hamas, it also would like the war in the Strip to end and to promote regional vision of peace and economic prosperity, aligning with its competition with China for global hegemony.

Under these circumstances, the final recommendation of this document is to implement a dual-pronged strategy combining military and political actions: an intensive and sustained military effort, aimed not only at eroding Hamas and its capabilities but also at laying the groundwork for the stabilizing of an governing alternative to Hamas; and in parallel, a political initiative to gradually construct a moderate governing alternative in the Gaza Strip, which would also support and accelerate the success of the military effort.

This strategy requires strong cooperation with Arab states, and it should be part of a regional agreement that includes normalization with Saudi Arabia and steps toward concluding the Israeli–Arab conflict. For the Palestinians, the political horizon envisioned in this strategy is one of limited independence and sovereignty. For Israel, the plan preserves security-operational freedom and continued efforts to eliminate Hamas and thwart emerging threats in the Strip, through a combination of military, economic, legal, and political measures.

This proposed strategy is indeed more complex to implement compared to the one-dimensional alternatives currently discussed in Israel. However, this strategy is realistic in terms of its practical feasibility, and unlike the other alternatives, it holds the potential to shape the Gaza Strip within a broad perspective of national interests, and through more intelligent and balanced risk and resource management: balancing security risks and needs in Gaza and other arenas, leveraging the political opportunity to end the Israeli–Arab conflict and create a regional alliance that would historically improve Israel’s strategic position, and taking into account the profound implications of the Gaza issue on Israel’s economy, politics, and society.

Preface

In the field of political-security thinking . . . the Yom Kippur War revealed the contradiction between the impressive development that had occurred in some Arab states, especially Egypt, since the Six-Day War, and the degeneration of Israeli political-security thinking. In this field was the real surprise of the Yom Kippur War … If one could have expected that following the national shock, the Israeli political leadership would formulate new hypotheses about the adversary, about itself in relation to the adversary, and about its relationship with the United States—its only ally—a system of hypotheses that would reflect the transformation in these areas that began with the war—this expectation was not realized.

—Tzvi Lanir, The Basic Surprise: Intelligence in Crisis (Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing, 1983), 97.

_______

Since October 2023, the State of Israel has been at war in the Gaza Strip, following the murderous terrorist attack carried out by Hamas on October 7. The Israeli government set three objectives for the war in the Strip: the collapse of Hamas’s rule, the destruction of its military capabilities, and the return of hostages that were taken during the attack.

On January 19, 2025, a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas came into effect. This was part of the initiation of a second deal between the two sides for the return of the Israeli hostages in exchange for the release of Palestinian prisoners, a gradual withdrawal of IDF presence from the Strip, and for the return of Palestinians to their homes in the northern Gaza Strip. About a month later, on March 18, Israel ended the ceasefire and resumed attacks in the Strip.

At the same time, the return of President Trump to the White House has upended the cards regarding the Gaza Strip. Trump has reintroduced and intensified the option of normalization between Israel and Saudi Arabia, which is supposed to include a political engagement with the Palestinian issue. At the same time, the US president presented an idea for the “voluntary emigration,” or evacuation of the entire Palestinian population from the area as part of a new vision for the Strip.

In between are the Arab states, which have formed a unified front rejecting the idea of evacuating the Strip and are attempting to promote an alternative vision of stabilizing Gazza through a Palestinian technocratic administration and a civilian reconstruction project that would not require population displacement. Simultaneously, Saudi Arabia is sharpening its demand for “paving a path toward the establishment of a Palestinian state” as part of the conditions for normalization with Israel.

Meanwhile, the strategic intentions of the current Israeli government regarding the Gaza Strip, in both the short and long term, remain unclear. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has adopted President Trump’s population evacuation plan as Israel’s new official policy for the “day after,” but continues to claim that normalization with Saudi Arabia will materialize in the near future.

The influence of widespread public sentiment in Israel on its Gaza policy cannot be overlooked. The events of October 7 left a deep scar on the Israeli public psyche, which will impact long-term positions regarding the nature of the conflict with the Palestinians and the security margins required concerning the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. On the other side, it is reasonable to assume that the extensive destruction of the civilian space in the Gaza Strip and the high death toll will significantly affect the positions of the Palestinian public. On the ground, the war has dramatically transformed the landscape of the Gaza Strip, effectively destroying most of it and creating a new geographic and demographic reality whose full implications for the coming years are still too early to assess.

Alongside all these factors, the future of the Gaza Strip—and of Israel’s relationship with the Strip—will not be shaped independently of developments in the regional and broader Palestinian systems. The war in the Strip expanded after October 7 into additional arenas, and its outcomes are changing the face of the Middle East and the balance of power between the various actors in the region, with repercussions that will in turn influence the Palestinian arena.

While the fate of the Gaza Strip remains unresolved, one prominent fact persists: Hamas remains, in practice, the governing and military power in the area. This situation, along with the absence of any alternative capable of threatening Hamas’s rule and the failure to return all the hostages to Israel, reflects Israel’s failure so far to achieve the war’s stated objectives.

The continued exIstence and rule of Hamas in the Gaza Strip is a disaster for Israel. It preserves the direct threat to the security of residents in the western Negev and may affect the willingness of residents to return to their communities and rehabilitate the area. Moreover, Hamas is vigorously promoting a victory narrative based on the steadfastness (sumud) and determined resistance, without any competing force challenging it within the Strip. At the same time, the idea of a political resolution in the West Bank Is also experiencing a setback. Under these circumstances, the idea of resistance is likely to become more deeply entrenched within Palestinian society, and the continued survival of the organization may further strengthen this idea across the broader Middle East.

Against this complex backdrop, the question that has remained unresolved throughout the months of war arises more urgently—”What should be done with Gaza?” This question, often framed as the “day after” Hamas’s rule, deals with the dilemma of how to shape a better strategic reality in the Gaza Strip in the coming years for the State of Israel. This document presents the various alternatives on the table, examines the implications of each, the risks and opportunities they entail, and the degree of legitimacy and feasibility of each alternative.

This document opens with working assumptions regarding the current situation, defines Israel’s strategic interests in relation to the Strip, and based on those assumptions and interests, analyzes the existing alternatives. Each alternative is examined in terms of its implications (military, economic, legal, and political), and in terms of its viability.

The analysis of alternatives was carried out using several methods: first, the work’s conclusions were discussed in brainstorming sessions and peer-reviewed at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS).[1] Second, the alternatives were discussed in several dialogue meetings with various experts in Western and Arab countries. Additionally, the “Palestinian Program” expert platform at INSS (which includes a number of Israeli researchers specializing in this field) was used to collect their graded opinions on the various alternatives.

_____________

[1] The author wishes to thank all the members of INSS who contributed their comments and insights to this document: Tamir Hayman, Udi Dekel, Ofer Shelah, Kobi Michael, Yohanan Tzoreff, Tammy Caner, Yoel Guzansky, Ofir Winter, Amira Oron, Esteban Klor, and Anat Kurz. Also, the author also thanks Reem Cohen and Noy Shalev for their assistance in preparing this document.

_____________

Working Assumptions

Hamas currently maintains its governing and military grip over the Gaza Strip

The IDF’s fighting in the Gaza Strip significantly damaged Hamas’s military frameworks (except in Deir al-Balah and the Nuseirat refugee camp in the Khan Yunis district, due to concern for the hostages held there). The military implication is that Hamas’s ability to carry out large-scale operations has been neutralized as a result of the erosion of its ground formations and the rocket capabilities of its military wing.

However, Israel has not succeeded in neutralizing Hamas’s ability to continue operating in terrorist and guerrilla patterns against IDF forces inside the Strip in an effective, even if sporadic, manner. Moreover, the terror organizations in the Strip retain the ability to carry out cross-border attacks against Israeli targets. This is due to the residual but extensive capabilities Hamas still has on the ground, as well as the presence of Hamas leaderships outside the territory. Notably, Hamas’s tunnel infrastructure—because of its extraordinary length (hundreds of kilometers)—remains partially operational, with some of it still usable, allowing movement between areas and shelter for operatives and weapons.

Even before the ceasefire came into effect, and more so afterward, Hamas began replenishing its fighting ranks with new recruits and is using the lull in fighting to prepare for its renewal. This includes booby-trapping areas (in part by using many of the IDF’s unexploded ordnance scattered around the area), and seizing control of humanitarian aid entering the territory, which allows it to collect money from the population in exchange for its distribution, and through this, pay salaries to volunteers and new recruits.

On the civil front, Hamas’s ability to operate its governance systems and maintain effective civil control across the Strip has been impaired due to the destruction of government structures and the pursuit of Hamas operatives by the IDF. Nevertheless, in the absence of an alternative to Hamas rule, the organization continues throughout the war to act as the de facto sovereign. Its members control the aid entering the Strip and its distribution, collect taxes on incoming goods, influence market prices through deterrence and violence, and work to maintain public order and pursue collaborators with Israel.[1]

On the popular level, Hamas effectively controls all parts of the Gaza Strip based on its operatives’ presence, from the mosque and neighborhood levels. It activates its Da’wah (outreach) networks and provides social assistance to the population alongside indoctrination activities. Simultaneously, Hamas is working to advance initial processes of returning the Strip to routine, such as renewing the school year, reopening of schools, and expanding the deployment of the civilian police.

The implications of Hamas’s continued control over the Gaza Strip are severe. Beyond the immediate and direct threats it poses, the continuation of its existence as a governing and movement-based entity in the Strip serves to reinforce the narrative of victory over Israel and strengthens the ethos of struggle and resistance against it among Palestinian society.[2]

There Is Currently No Internal Alternative to Hamas in the Gaza Strip

It is difficult to reliably assess public support for Hamas among the residents of the Gaza Strip. A series of surveys conducted throughout 2024 indicated support levels that did not exceed one-third of the public. This pertains to questions regarding the degree of support for Hamas, its leaders, and preference for it as the governing alternative for the “day after.” However, it is important to emphasize the potential biases in these surveys (as reflected in the relatively large variance among them), and the potential for changes in the ttitudees of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, given that the surveys were conducted during wartime and while the respondents were staying in humanitarian shelters.[3]

Conversely, an analysis of discourse on Gaza’s social media platforms reveals a significant blow to the legitimacy of Hamas’s continued control of the Strip. There are news articles reporting residents’ anger at the organization following the war and its consequences, and social media posts from Gaza residents reinforce this impression.[4] In late March 2025, protests began to emerge in various areas of the Gaza Strip, involving hundreds and thousands of residents demonstrating against Hamas rule. These were sparked by the collapse of the ceasefire and the renewal of fighting, during which the protesters demanded an end to the war and even to Hamas’s rule.

At the same time, however, it is important to recognize that Hamas is not an external, new, or transient phenomenon in the Palestinian experience—and even more so in that of the Gaza Strip—but is deeply and fundamentally rooted in it. Hamas was born in the Gaza Strip; its members are local, operating not only through organizational networks but also through family ones. Over its decades of existence, Hamas has succeeded in embedding its religious-nationalist political consciousness into Palestinian society through extensive activism in all areas of life (especially in religious and educational systems, public spaces, and charitable networks). The generation that has grown up in the Gaza Strip over the past two decades—during which Hamas has ruled the area without restraint and without any real opposition—does not know of an alternative to Hamas.

In this context, it is also important to note that, to this day and at no stage throughout the war, have there been expressions within Palestinian society of introspection or self-criticism following the October 7 attack. The heinous acts committed by Hamas (and by the second wave of mobs that arrived after Hamas’s assault) are dismissed as the acts of individuals, as natural responses to the “crimes of the occupation,” and mostly as false accusations.[5]

The Civilian Situation In the Gaza Strip Is Unsustainable Without Extensive Reconstruction, but the Future of Reconstruction Is Unclear[6]

Physical Destruction and Housing Infrastructure: The extent of civilian destruction in the Gaza Strip is immense. The north and center of the Strip have suffered the most damage, corresponding to the areas where the IDF conducted its ground operations. According to data from the Ministry of Public Works in Gaza, which operates under the Hamas government, as of the end of December 2024, about 70% of the housing sector had been destroyed. This includes 170,000 housing units that were completely destroyed, and 80,000 residential buildings that were partially damaged. The overall damage in the Strip is estimated at tens of billions of dollars, affecting not only homes but also critical infrastructure such as major roads like Salah al-Din Road. Moreover, around 80% of access roads between different districts in the Strip have been completely destroyed.

Electricity: According to OCHA (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs) and INSS, even before the war, electricity supply in Gaza was limited to about 4–8 hours per day. Today, the power grid has almost completely collapsed. Gaza’s only power plant was severely damaged, and electricity supply now relies on local generators and fuel transferred through Egypt.

Water and Sanitation: According to the WHO (World Health Organization) and OXFAM, Gaza’s water systems have nearly shut down due to extensive damage to desalination facilities and critical wells. The population now relies entirely on water trucks and external tank deliveries for drinking water. In addition, more than 60% of the sewage system has been damaged, causing water contamination and posing severe health risks.

Food Supply: UNRWA and WFP (UN World Food Program) report that local agriculture has been heavily affected by the destruction of fields and a lack of fuel for irrigation systems. There is a severe shortage of essential items, such as flour, oil, and meat, raising concerns among international organizations about potential death from malnutrition. Currently, around 80% of the population relies on direct humanitarian aid.

Healthcare System: According to Hamas’s Ministry of Health, over 50,000 people have been killed and more than 113,000 injured since the war began, in a population of approximately two million. The risk of epidemics is rising, with many bodies still buried under the rubble. Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross report that most hospitals have been damaged, and those still functioning are operating at over 300% capacity. There is a severe shortage of medicine and critical medical supplies, including antibiotics, surgical tools, and insulin. Furthermore, restrictions on evacuating the wounded for treatment outside the Strip limit access to adequate care.

Local Economy: According to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, about 90% of Gaza’s local industry has ceased operations, including major industrial zones in eastern Gaza City. The collapse of the private sector and the paralysis of commerce have led to mass unemployment, with estimates indicating that 80% of the employable population is jobless. Economic activity in the Strip is now largely confined to limited humanitarian trade through Egypt.[7]

Given the extensive destruction of essential infrastructure, the Gaza Strip is now considered by many as largely uninhabitable. Without reconstruction, this reality is expected to accelerate widespread radicalization and lead to chaos and severe humanitarian crises, which will have direct consequences for Israel.

Rebuilding Gaza’s civilian infrastructure would require costs of tens—or some argue even hundreds—of billions of dollars, and the reconstruction effort would take years. However, questions regarding the sources of funding and the motivation to reconstruct the Gaza Strip remain unresolved. To a large extent, these questions are more political than economic. The willingness of regional and global actors to contribute to the funding of Gaza’s reconstruction will depend on the political horizon of the Strip and the identity of the ruling power there—whether Hamas, Israel (in a scenario of occupation and military rule), the Palestinian Authority (PA), or another Palestinian entity not affiliated with Hamas.

Israel Can Suppress Hamas in Gaza Through Military Means Alone—But Not Eliminate It

According to media reports, the IDF’s updated war plans include the full occupation of the Gaza Strip and the imposition of military rule, to advance the goal of fully eliminating Hamas.[8] If the IDF were to implement these plans, the assessment of the potential achievement would depend on several components—some positive, others negative:

- On the positive side: The IDF has refrained from operating in certain areas of the Gaza Strip due to concern for the lives of hostages, allowing Hamas to maintain its presence there. Should more hostages be released, this constraint on the IDF’s operational capacity may be reduced. Furthermore, assuming the Trump administration continues to support Israel’s military action, it will provide Israel with broader political backing than it did in the past for higher-intensity fighting and in dealing with the diplomatic and legal arenas.

- On the negative side: Severe and prolonged damage to Hamas’s military, governmental, and organizational infrastructure in Gaza—modeled after the “mowing the grass” strategy used in the West Bank—would require occupying the entire Strip. This would involve deploying multiple divisions over several years to take over, clear, and hold the territory. This scenario must be considered in light of the gaps in the IDF’s force structure, fatigue and performance deterioration in the army,[9] the need to allocate forces to other active fronts (currently the West Bank, with potential escalation in Lebanon due to ceasefire implementation challenges, or along the Syrian border), and the economic slowdown due to the prolonged war, which would also limit Israel’s ability to sustain such an extended military campaign.

Based on these considerations, this document assumes that if the IDF is tasked with occupying the Strip, it could significantly and sustainably suppress Hamas—preventing it from regaining control, and severely damaging its military infrastructure. However, such an achievement would come with steep costs to the Israeli economy, society, and, to some extent, the management of broader security risks. Even in this scenario, Hamas would not be totally eradicated but rather its strategic threat to the State of Israel could be neutralized. If Israel desires, this move could provide time to establish a moderate alternative to Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

The Interests of the Trump Administration and the Israeli Government Regarding the Gaza Strip Do Not Fully Align

The Biden administration, early in the war, put forth an initiative linking the stabilization of the Gaza Strip with normalization between Saudi Arabia and Israel, as a mechanism for exiting the war and addressing the “day after.” This linkage reflected an understanding that, after October 7, Saudi Arabia—as the current leader of the Arab camp—could not move forward toward resolving the Israeli–Arab conflict without progress toward the establishment of a Palestinian state. Simultaneously, resolving Israeli–Palestinian relations could not be realized without a regional framework offering further incentives to Israel and guarantees to the Palestinians. Specifically, regarding Gaza, the Biden initiative aimed to enlist Arab states to invest financial and other resources to help stabilize and rebuild the Strip.

The return of the Trump administration in January 2025 reshuffled the deck concerning Gaza’s political horizon. The American president laid out a series of far-reaching, yet contradictory, objectives regarding the Gaza Strip. On the one hand, he expressed a desire to end the war and reach an agreement with Saudi Arabia—which clearly would need to include some form of political recognition of Palestinian rights. On the other hand, he proposed US control of Gaza that would require the evacuation of its entire Palestinian population. In an interview at the end of March, President Trump’s Middle East envoy, Stephen Witkoff, expressed understanding for Israel’s resumption of combat against Hamas but also emphasized the need to advance a political resolution in the Strip—without ruling out the inclusion of Hamas in the new order, if it disarms.[10] His comments suggested that ending the war and moving to Gaza’s stabilization phase was important for several reasons: preserving the stability of Egypt and Jordan, laying the groundwork for expanding the Abraham Accords—which would include Saudi Arabia—with the goal of establishing a thriving Middle Eastern economic bloc to counterbalance the European Union.[11]

From a pragmatic analysis of interests, the deal with Saudi Arabia is clearly preferable for the Trump administration over the “real estate option” in the Gaza Strip, due to significant geostrategic and economic considerations. The deal is expected to yield transactions worth tens—or even hundreds—of billions of dollars for the United States (with Trump-affiliated companies likely to benefit, based on past experience with the Abraham Accords)[12] and enable the realization of the IMEC initiative (an economic corridor linking Europe and Asia via the Middle East), which would compete with China’s Belt and Road Initiative and strengthen US influence from the Middle East to the Far East. However, the deep uncertainty surrounding President Trump’s policies undermines the level of confidence of this assumption.

There Is Consensus in the Arab World on the Need for Palestinian Rule in Gaza, but No Agreement on Its Identity

Arab states strongly oppose the implementation of the idea of emigration for Gaza’s Palestinian residents. Aside from this point of consensus, they appear divided on the remaining questions regarding Gaza’s future. This complexity was reflected at the Arab League Summit held on March 4, 2025. On the surface, the summit’s messages presented a united front regarding the principles for dealing with the dilemmas surrounding Gaza in the post-war period:

- The “removal” of leadership over Gaza’s reconstruction and the Palestinian issue from the Palestinians themselves, transferring it to an “Arab-Islamic conference” headed by Saudi Arabia.

- Gaza’s reconstruction will not advance as long as Hamas maintains political and military control of the Strip. The committee to fund the reconstruction will only convene—if at all—in April 2025, and only once Hamas’s governing future is clarified.

- The future Gaza Strip will be based on a single political regime, one law, and one source of arms.

- The Arab position restores the PA to the role of the central power that will govern the Gaza Strip in the future (with the Palestinian police to receive training in Egypt and Jordan), following a transitional period during which the Strip will be managed by a “civil committee.”

- The Egyptian plan for Gaza’s reconstruction is the exclusive framework.[13]

In practice, the summit did not conclude with significant decisions due to several factors—chief among them, internal disagreements between the participants and, apparently, the presentation of the above principles as a starting point for negotiations with the Trump administration. These disagreements were evident even in the weeks leading up to the summit:

- Egypt is focused on mediating between Hamas and Fatah, seeking mutually acceptable transitional arrangements for governing Gaza.

- Saudi Arabia seeks to eliminate Hamas’s political and military leadership and expel the organization’s leaders from the Strip.

- The UAE desires extensive reforms in the PA and a complete overhaul of the educational system in the Gaza Strip.

- Qatar aims to ensure Hamas’s political and military survival and maintain its role in Gaza’s administration.

Gaza’s Future Will Also Be Influenced by the Ideological Struggle Within Sunni Islam, Expected to Intensify Following the October 7 War

The October 7 war triggered shockwaves throughout the Middle East, the full effects of which are still too early to assess. What appears to be at least a temporary weakening of the Iranian axis could lead to a renewed rise in rivalries and conflicts within Sunni Islam—between the radical Islamist camp and the moderate camp. The rise of a new regime in Syria with an Islamist orientation and ties to Turkey under Erdoğan’s leadership may signal the beginning of a new wave of extreme political Islam in the Sunni world. This could also impact Iraq, Jordan, and the West Bank, and in a worst-case scenario, create a “Sunni Crescent” that would destabilize local regimes.

In other words, under the cover of war, the familiar dynamics and balance of power between the regional blocs—the Iranian-Shiite axis, the Sunni political Islam axis, and the moderate Arab axis—are once again being challenged and reshaped. These struggles, and the new balances that will emerge from them, will also affect the Palestinian arena, including the regional orientation of Hamas and the Palestinian system as a whole, which has always operated within a complex web of regional interests in an effort to navigate and balance them.

_______________

[1] Elior Levy, “The Pressure, the Looting, and the Control: What They’re Not Telling You About Humanitarian Aid to Gaza,” Breaking Walls: Episode 2, Kan 11, December 6, 2024 [Hebrew], https://www.kan.org.il/content/kan/news-series/p-837561/s1/833005/.

[2] Kobi Michael, “The Question Nobody’s Asking: Is It Even Possible to Rehabilitate the Gaza Strip Under Existing Conditions and if Not, What Then?” Strategic Assessment 28, no. 1 (March 2025), https://www.inss.org.il/strategic_assessment/gaza-strip-rehabilitation/.

[3] Kobi Michael, “What Can We Learn from the Public Opinion Polls in Palestinian Society,” INSS Insight, No. 1907, (November 12, 2024), https://www.inss.org.il/publication/palestinian-survey-2024/.

[4] Orit Perlov, “Trends in Palestinian Public Discourse,” INSS Insight, No. 1957 (March 11, 2025), https://www.inss.org.il/publication/palestinian-discourse/.

[5] Michael Milshtein, “After the Cease-Fire Deal: The Palestinians Experienced a Nakba, But Feel Victorious,” Ynet, February 2, 2025, https://www.ynetnews.com/article/hkmdxm3o1x.

[6] The data regarding the scale of destruction and casualties in Gaza is constantly changing and being updated. The figures presented here are accurate as of March 2025.

[7] OCHA, “Humanitarian Situation Update, Gaza Strip” No. 247 (December 17, 2024), https://www.ochaopt.org/content/humanitarian-situation-update-247-gaza-strip.

[8] “Will Hamas Fold, The Plan for Occupying Gaza Was Leaked and It’s Going to Be Cruel,” Maariv, February 28, 2025 [Hebrew], https://www.maariv.co.il/news/military/article-1182929.

[9] In the final months of the fighting, the erosion of forces was evident in the IDF’s performance; units faced an unprecedented burden of continuous combat for over a year. Reliable reports indicate a decline in discipline, the departure of mid-ranking officers—which even the IDF acknowledges is approaching a full-blown crisis—and a growing number of cases of “gray refusal” to report for reserve duty, as well as incidents of violations of the rules of engagement, including the killing of civilians, unnecessary destruction of buildings and infrastructure, looting, and humiliation of the civilian population. These phenomena, some of which are even documented on social media, are not being seriously addressed by the various levels of command.

[10] Tucker Carlson, “Steve Witkoff’s Critical Role in Negotiating Global Peace, and the Warmongers Trying to Stop Him,” The Tucker Carlson Show, YouTube, March 24, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=acvu2LBumGo.

[11] Pinchas Inbari, “Witkoff’s Real Plan,” Zman Israel, March 26, 2025 [Hebrew], https://www.zman.co.il/575001/.

[12] Eytan Avriel, “The Guest of Honor: Jared Kushner’s Method of Profit-Driven Diplomacy,” TheMarker, March 3, 2025 [Hebrew] https://www.themarker.com/magazine/2025-03-03/ty-article-magazine/.highlight/00000195-5638-d544-a795-deb890360000.

[13] Embassy of Egypt, Washington DC, “Gaza Recovery, Reconstruction & Development Plan,” March 2025, https://egyptembassy.net/media/Gaza-Recovery-Reconstruction-and-Development-Plan.pdf.

_______________

Strategic Alternatives for the Gaza Strip

The list of strategic alternatives for the Gaza Strip was formulated through a broad survey of the various options raised in the Israeli, Arab, and international discourse—both concrete initiatives proposed by official entities and suggestions from research institutes and commentators. All the proposals and initiatives can be categorized into four main alternatives:

- Encouraging Voluntary Emigration—the evacuation of most or all of the Palestinian population from the Gaza Strip, and the imposition of Israeli or American sovereignty over it. This alternative, which was previously outside the normative discussion framework, became a formal policy direction of the United States and Israel shortly after President Trump’s return to power.

- Military Rule—Israeli military occupation of the Gaza Strip, or parts of it, over an extended period.

- Continuation of the Status Quo—this alternative essentially stems from a reality in which Israel refrains from promoting military or political initiatives in the Gaza Strip, or fails in the initiatives it attempts to advance.

- Alternative Palestinian Governance—this alternative addresses the establishment of a moderate Palestinian administration, with Arab and international support, which would replace Hamas in governing the Gaza Strip.

The range of alternatives analyzed in this document excludes several options discussed in public discourse that appear unrealistic and fall outside the framework of practical feasibility. These include proposals from some Palestinian research groups, such as the establishment of a local administration under joint Fatah-Hamas control, or the imposition of Egyptian rule over the Gaza Strip.[1] The analysis also excludes short-term transitional alternatives, such as the “islands plan” promoted by “HaBitkhonistim” (Israeli security veterans),[2] and instead focuses on long-term alternatives (although intermediate solutions may be integrated into long-term strategies as part of their gradual implementation).

The alternatives are “synthetic,” meaning they are presented in their complete and ideal form for the sake of clarity in analysis, and as such are mutually exclusive. However, in practice, reality may unfold in various complex ways, with one alternative potentially following another (e.g., military rule followed by efforts to stabilize a Palestinian governance alternative to Hamas), and scenarios may emerge that combine multiple alternatives (e.g., military rule in one part of Gaza and Hamas control remaining in another geographic area).

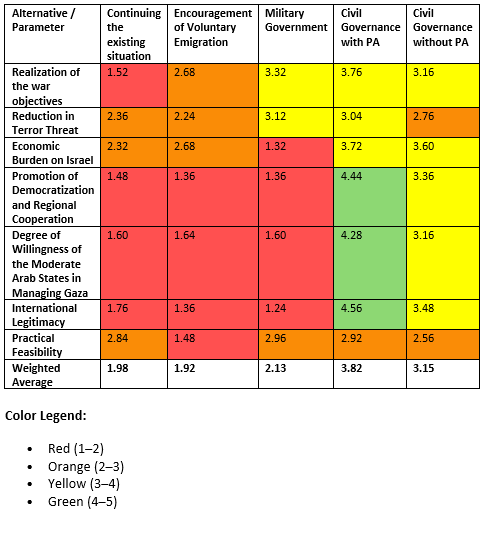

Each alternative is assessed based on its implications—mainly in the military, economic, and political-legal dimensions—and its practical feasibility, derived from the legitimacy it would receive from Israel, the United States, the Palestinians, and Arab states. The alternatives presented were also subject to critical review through several methods: peer review by experts in Israel, the region, and globally, and the use of the “wisdom of experts” platform from the Palestinian Arena Research Program at INSS, to gather their scored opinions on the different alternatives.

____________

[1] See, for example, Ghazi Abu Jiyab, “Scenarios from Gaza for the Day After the War,” The Forum for Regional Thinking, July 2024 [Hebrew], https://www.regthink.org/shaban-day-after/.

[2] Yifa Segel, Lt. Col. (res.) Yedid Baruch, and Jennifer Teale, “The Gaza Humanitarian Islands Plan Interim Phase,” HaBitkhonistim, December 19, 2024, https://idsf.org.il/en/papers/the-gaza-humanitarian-plan/.

____________

Israeli Interests in the Gaza Strip

Defining Israeli interests in the context of the Gaza Strip is particularly challenging at this time for two interlinked reasons. First, it is difficult to separate the definition of interests from the context of the existing strategic options already present in public discourse. Specifically regarding Gaza, it is currently difficult to define a sufficiently flexible framework of interests that can encompass the wide range of alternatives circulating in Israeli and international discourse—ranging from the establishment of a Palestinian state to the encouragement of emigration.

Secondly, the added complexity arises from the absence of a basic national consensus and the presence of deep divisions in Israeli society and politics, both regarding the interests themselves and the ethical-moral aspects concerning the boundaries of what is permissible within the alternatives that could serve to realize those interests.

As a framework for analyzing the various alternatives for Gaza’s future, the following definition of Israeli interests is proposed:

- The return of the hostages.

- The destruction of Hamas in the Gaza Strip—or at minimum, reducing it to a marginal force militarily and politically, and preventing its integration into governing mechanisms in the Strip. This includes preventing a renewed rise of Hamas rule as a platform for seizing control over the broader Palestinian system, including in the West Bank.

- Preservation and strengthening of stability and security for Israel, especially for residents of the border area, and the removal of security threats from Gaza posed by Hamas or any other actor.

- Civil stabilization and prevention of a humanitarian collapse in Gaza, as a basis for reducing security threats and humanitarian crises that could spill over into Israel.

- Containment of military resources invested in the Gaza Strip, to ease the allocation of resources for other fronts, especially regarding Iran and the northern arena.

- Containment of economic resources invested in Gaza and sharing the burden of its stabilization and reconstruction with other parties. This is especially crucial given the heavy costs of war, the cost of rebuilding Gaza, and global economic uncertainty amid intensifying trade wars in international relations.

- Reducing Israel’s responsibility for the Strip and minimizing Gaza’s dependency on Israel.

- Preventing negative political and legal ramifications for Israel, stemming from its policies and actions in Gaza (such as lawsuits from international courts).

- Preserving existing agreements with Arab states and removing the Palestinian issue, including Gaza, as an obstacle to normalization with Saudi Arabia and to advancing a regional economic-security coalition with moderate Arab states.

- Minimizing the influence of Iran, Qatar, and Turkey in the Gaza Strip.

This document does not categorically reject objectives such as imposing Israeli sovereignty over Gaza or reestablishing Jewish settlements there. However, from a security-strategic analysis (as distinct from a faith-based perspective), these are not considered core interests but rather potential objectives within a broader strategy to fulfill national interests. Similarly, the idea of encouraging Palestinian emigration from Gaza on one hand, or restoring the PA’s rule in Gaza on the other, are viewed within this framework as possible components of an Israeli strategy—but not as foundational Israeli interests.

Barriers and Tensions

The ability to realize Israel’s interests in relation to the Gaza Strip faces serious challenges, due to the complexity of the issue. Numerous variables must be taken into account, and the various possible solutions are difficult to implement and require planning and execution over time, under circumstances of a highly dynamic reality—sensitive to crises and difficult to control. It can be said that the central problem is the lack of synchronization between the different “clocks”: the hostage clock, which is urgent; the military clock, which is constantly aimed at dismantling Hamas; and the civil-political clock of stabilizing an alternative reality to Hamas’s rule in the Gaza Strip.

Specifically, several barriers and tensions can be identified with regard to the ability to realize Israeli interests:

- Returning the hostages vs. suppressing Hamas—Military pressure endangers the lives of the hostages, and attempts to rescue them through military operations may lead to their deaths at the hands of their captors. On the other hand, deals to bring them back require easing military and civil pressure on the Strip, in a way that helps Hamas re-tighten its control on the ground.

- Timing of reconstruction relative to Hamas’s condition—It makes sense to delay the reconstruction of Gaza until Hamas is suppressed and there is assurance that it will not benefit from the reconstruction and use it to re-fortify its rule. At the same time, however, reconstruction itself is a tool for deradicalization and for preventing scenarios of chaos and humanitarian and other crises.

- Dual effect of Israeli military activity and presence in the Strip—On one hand, Israel is the only actor capable and willing to militarily suppress Hamas in a way that would allow a political and governmental alternative to emerge that will not operate under the constant threat of Hamas opposition. On the other hand, prolonged and indefinite Israeli activity in the Strip, without a broader stabilization strategy, may deter external players from investing in Gaza’s reconstruction and limit the ability of a new government to demonstrate independence.

- The principle of differentiation vs. the advantages of involving the Palestinian Authority—Involving the PA in building the governmental alternative to Hamas in Gaza could significantly ease the willingness of moderate Arab states to contribute to Gaza’s stabilization and reconstruction efforts, within the framework of arrangements between the PA and Israel, and under the umbrella of a political horizon. Conversely, involving the PA without implementing significant reforms would harm the long-term stabilization processes of the Strip.

- The Qatari role—Qatar currently plays a vital role in the negotiations for the release of hostages with Hamas, which views it as a fair and favorable mediator. Qatar could also be a significant contributor to funding Gaza’s reconstruction. However, fundamentally and in the long term, Qatar plays a destabilizing and negative role through its support for Hamas, as reflected during the war in the coverage by Al Jazeera and its financial backing of Hamas.

Israel’s Policy

Before analyzing the strategic alternatives, it is important to place them in the context of the official policy of the State of Israel, which has changed over time. On the eve of the military campaign in the Gaza Strip, the government defined the war’s objectives as the destruction of Hamas’s military and governing capabilities and the return of the hostages.

To meet these maximalist objectives, the government outlined a prolonged and phased war plan, as detailed by then-Defense Minister Yoav Gallant on the eve of the ground maneuver: “This is a campaign of three organized stages . . . We are currently in the first stage, involving military operations—firepower and then maneuvering—aimed at destroying operatives and damaging infrastructure to bring about the collapse and destruction of Hamas. The second stage will be an intermediate phase of continued lower-intensity fighting and elimination of resistance pockets. The third stage will be the creation of a new security regime in the Gaza Strip, the removal of Israeli responsibility for life in the Strip, and the creation of a new security reality for the citizens of Israel and the residents of the south.”[1] Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated in an interview with Fox News on November 9, 2023, that, “We do not aspire to conquer Gaza, to hold Gaza, or to govern Gaza. We will need to find a civilian government to be there.”[2]

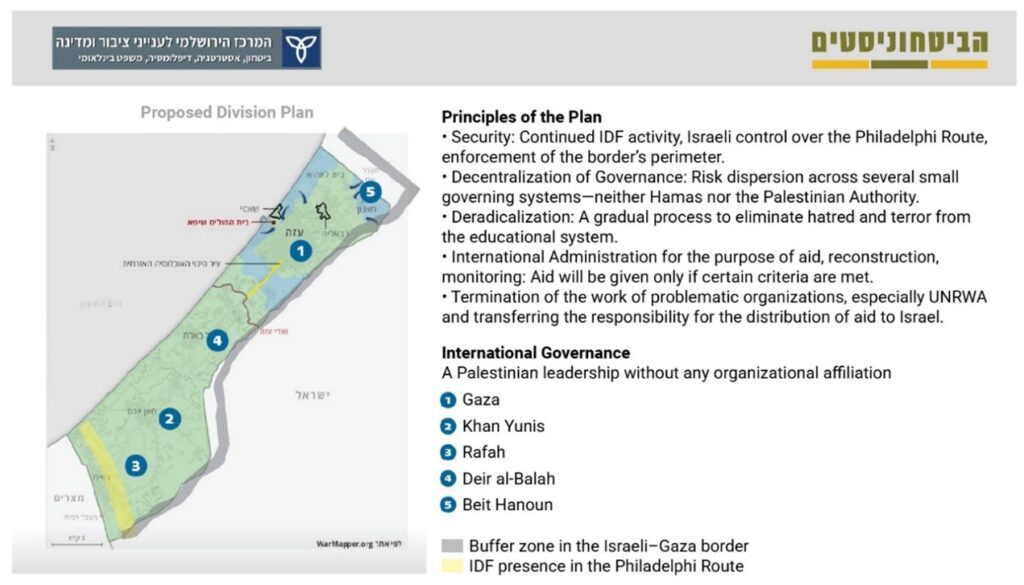

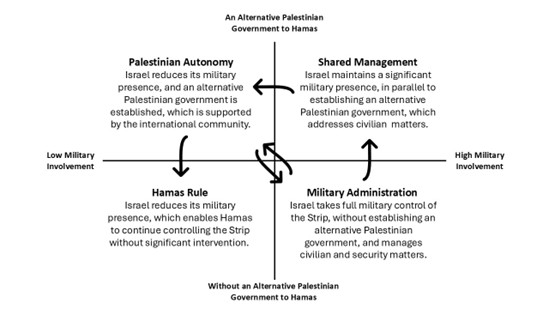

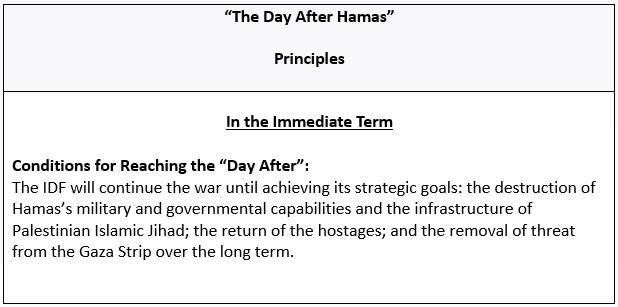

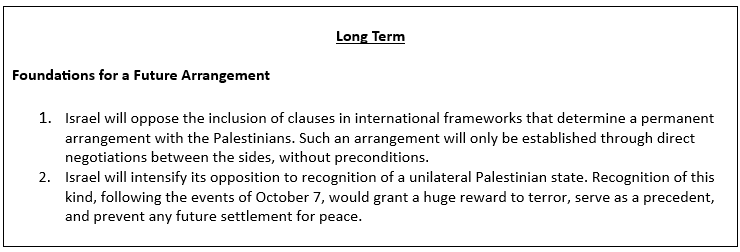

On February 23, 2024, Prime Minister Netanyahu published a document titled “The Day After Hamas,” detailing Israel’s objectives regarding the Gaza Strip (see Figure 1).[3] The document outlines military and civilian goals for the interim period following the phase of intense combat and appears to provide substance to the third stage of Gaza’s stabilization.

Figure 1.

In the military realm, the goal was defined as “complete demilitarization of the Gaza Strip from all military capabilities, beyond what is required for maintaining public order.” It further stated that “the responsibility for realizing this objective and supervising its implementation for the foreseeable future lies with Israel.” To that end, Israel “will retain freedom of operational activity throughout the Gaza Strip, without time limitation,” including the existence of a security buffer zone along the Gaza-Israel border (“the perimeter”) “as long as a security need exists”; control over the Philadelphi Route (“southern closure”), to the extent possible, in coordination with Egypt and with US support, relying on measures to prevent smuggling from Egypt both underground and above ground, including at the Rafah Crossing.”

In the civilian realm, the prime minister declared that “as much as possible, civilian administration and responsibility for public order in the Gaza Strip will rely on local actors with administrative experience,” who are not affiliated with states or entities that support terrorism. He also stated that a comprehensive deradicalization program would be promoted in all religious, educational, and welfare institutions in Gaza, with the involvement and support of Arab countries that have relevant experience. The deradicalization plan would also include Israeli action to close UNRWA, terminate its operations in the Strip, and replace it with responsible international relief agencies. Regarding reconstruction, the prime minister defined that it would take place only after the completion of demilitarization and the beginning of the deradicalization process, with funding and leadership by countries acceptable to Israel. In a discussion at the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee (held on December 11, 2023), Netanyahu said that the Gulf states would lead the reconstruction.[4] Regarding the longer term, Prime Minister Netanyahu refrained from giving a positive vision of the desired political reality in the Gaza Strip and limited his remarks to expressing opposition to international dictates regarding a permanent settlement with the Palestinians and to unilateral recognition of a Palestinian state.

The strategic framework laid out by the prime minister for the day after the war, as presented in the document, includes Israeli military occupation and Palestinian local civilian administration with international support. This approach preserves several familiar principles from Netanyahu’s view of Gaza and the Palestinian system prior to October 7: maintaining separation between the two Palestinian entities in Gaza and the West Bank, opposing the return of the PA to Gaza, avoiding the creation of a political or ideological alternative to Hamas, and relying on military power as the central guarantee for preserving Israeli interests. The document does not address how support from the Gulf states for Gaza’s reconstruction will be obtained in the absence of a political horizon for the Palestinians. The strategy it reflects embodies an adherence to conflict management, and its practical implication is that responsibility for Gaza’s civilian administration will fall on Israel.[5] At the same time, Netanyahu has stated that renewed Israeli settlement in the Gaza Strip is not realistic.[6]

Foundations for a Future Arrangement

A year later, in February 2025, Prime Minister Netanyahu revised his stance on Israel’s long-term strategy toward the Gaza Strip and defined the “day after” plan as President Trump’s plan for the evacuation of the entire Palestinian population from the Gaza Strip. The current Minister of Defense, Israel Katz, instructed the IDF to formulate a plan for implementing Trump’s plan, and according to a media report, the Ministry of Defense is establishing a “Voluntary Emigration Directorate.”[7]

It should be emphasized that in the statements of senior Israeli officials, there is no reference to President Trump’s remark that Israel will be responsible for stabilizing the territory in the Gaza Strip—and implicitly for evacuating the Palestinian population—and will then transfer the territory to US control. Likewise, no members of the Israeli government have commented on the tension between the end-state defined by President Trump and the objective of annexation and the renewal of Jewish settlement in the Gaza Strip, to which significant parts of the coalition and government remain committed.

__________

[1] Yoav Zeitun, “Gallant’s Three-Stage Plan: From the Erasure of Hamas to the Creation of a ‘New Security Regime,’” Maariv, October 20, 2023 [Hebrew], https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/hywf301m6.

[2] Almog Boker and Moriah Asraf, “Netanyahu: ‘The IDF Will Continue to Hold the Gaza Strip Even After the War,’” Reshet 13 News, November 20, 2023 [Hebrew], https://13tv.co.il/item/news/politics/security/netanyahu-statement-903797403/.

[3] Suleiman Maswadeh, “Netanyahu Presented the ‘Day After’ Document Submitted for Cabinet Approval,” KAN 11, February 23, 2024 [Hebrew], https://www.kan.org.il/content/kan-news/politic/709398/.

[4] Shirit Avitan Cohen and others, “Netanyahu at the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee: ‘The Number of Victims on October 7 Is Like the Oslo Accords,’” Israel Hayom, November 11, 2023 [Hebrew], https://www.israelhayom.co.il/news/geopolitics/article/14935530.

[5] Udi Dekel, “‘The Day After’ Hamas’s Rule in Gaza: Time to Sober Up From the Illusions,” Special Publication, INSS, March 17, 2024, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/the-day-after-hamas/.

[6] Yael Ciechanover, “A Return to Jewish Settlement in Gush Katif? Netanyahu Has Already Clarified: ‘Not a Realistic Goal,’” Ynet, November 12, 2023 [Hebrew], https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/sjdn4yrqt.

[7] Almog Boker, “Defense Minister Instructs: Voluntary Emigration Directorate Set to Launch,” N12, February 17, 2025 [Hebrew], https://www.mako.co.il/news-military/2025_q1/Article-9d314901be41591026.htm.

__________

Analysis of Alternatives

Alternative A: Encouraging Voluntary Emigration of the Palestinian Population

Shortly after taking office, President Trump stated that the solution for the Gaza Strip is the complete evacuation of the area’s residents, without permission to return. According to his view, the territory would become a real estate project under American ownership, with Israel responsible for evacuating the Palestinians. The real estate project would not be financed by the United States, but rather by state-backed investors and private capital. He said that Palestinians could relocate to various locations across the Middle East and beyond, including Jordan and Egypt. Prime Minister Netanyahu quickly adopted the initiative as the new “day after” policy, and it was reported that the Ministry of Defense has already begun the process of establishing a “Voluntary Emigration Directorate,” following Defense Minister Katz’s directive for the army to prepare accordingly.

Among those involved in the issue, there is debate over whether this represents President Trump’s actual policy or is merely a tactical pressure tool intended to shake Arab states and push them to become more actively involved in resolving the Gaza problem. There is reason to believe this is indeed a genuine policy. The main ideas were presented by Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and close advisor, as early as March 2024 (in which he proposed relocating Palestinians to the Negev).[1] It is possible Trump was exposed to the idea through a plan developed by Professor Joseph Pelzman, an economist and head of the CEESMENA Institute, who claimed to have passed it on to Trump’s team back in July 2024.

According to the plan, evacuating the Palestinians is necessary to allow for Gaza’s reconstruction. They would be permitted to return only after the deradicalization of Gaza’s education system and Israel’s ability to technologically monitor them using biometric data. The local economy would be rebuilt based on three sectors: tourism, agriculture, and basic-level high-tech. Reconstruction would be implemented through the BOT (Build, Operate, Transfer) method, meaning that at least a significant portion of the funding would come from private investors, who would collect payments for several decades for the use of the infrastructure they establish, until transferring ownership to a public entity. The estimated cost of the project ranges from half a trillion to one trillion dollars.[2] Conversely, senior figures in the Trump administration have hinted that this is a pressure lever on Arab states, as suggested by remarks from Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who stated, “If people don’t like the Trump plan for Gaza, right now it’s the only plan. And so I think it’s now incumbent upon the Arab countries—our allies; we work very closely with them—if they think they’ve got a better plan, we need to hear it.”[3]

Arab states indeed reacted with shock and concern to the new policy, presenting it as a serious threat to their national security and an injustice to the Palestinians and their rights. They categorically rejected the possibility of absorbing Palestinians into their territory. At the same time, they are promoting an Arab initiative to remove the evacuation idea from the agenda, based on an Egyptian proposal: a reconstruction plan for Gaza funded and carried out by Arab countries, without the need to evacuate the population, and replacing Hamas rule with a local technocratic administration, with some connection to the PA. Hamas has expressed its general agreement to the Egyptian framework, while refusing to disarm or to allow any non-Palestinian forces to enter the Gaza Strip or intervene in its civil affairs. However, the American administration rejected the Egyptian initiative, claiming it ignores the reality of destruction and the necessity of eliminating Hamas.

As far as is known, the American population evacuation initiative has not yet been translated into a concrete action plan by the administration (perhaps partly due to expectations that Israel will be the one to implement the idea). Since the idea remains on the table and is an official policy of both the United States and the State of Israel—and in light of its profound moral and strategic implications—it is important to examine the practical feasibility of the evacuation initiative and the implications should concrete steps be taken to carry it out.

First, the question arises: to what extent are Palestinians currently interested in leaving the Gaza Strip? According to past data, since Hamas took control of Gaza in 2007, around 250,000 young people aged 18–29 have left the Strip due to the economic and security situation, Israeli restrictions, employment difficulties, and a loss of hope for the future. This represents a relatively low emigration rate of about 15,000 people per year, although it was likely influenced by exit barriers such as restrictions at the Rafah Crossing and the costs of paying smugglers or bribes to Egyptian security personnel. A survey conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, headed by Dr. Khalil Shikaki, between September 28 and October 8, 2023, found that 44% of the Strip’s youth (ages 18–29), 38% of all men, and 31% of Fatah activists (compared to 14% of Hamas activists) had considered emigrating. Among all respondents, 54% cited economic reasons as the main factor for wanting to emigrate, followed by educational opportunities (18%), security reasons (7%), corruption (7%), and political reasons (5%). Turkey was mentioned as the leading destination (22%), followed by Germany (16%), Canada (12%), and Qatar (10%).[4] Since the war began in October 2023, according to unverified estimates, 250,000–300,000 Palestinians have left Gaza, mainly to Egypt. It is estimated that the Strip’s current population is just under two million people.

It would be inaccurate to extrapolate from past data how many Palestinians would currently want to leave Gaza. On one hand, a greater percentage is likely interested in leaving due to the destruction, bleak future, and the loss of anchors tying residents to their homes—housing, infrastructure, and workplaces. On the other hand, many may insist on remaining in Gaza out of a principle of steadfastness and attachment to the land, as a form of defiance against the American–Israeli move to evacuate them—perceived as expulsion—or due to Hamas forcibly preventing them from leaving.

Suppose that only those who are staunch Hamas supporters would refuse the “voluntary” evacuation option, and the rest would agree. Various estimates put Hamas supporters at about one-third of Gaza’s residents. Given a population of approximately two million, this would mean about 600,000 Palestinians would refuse to leave the Strip voluntarily. While this is significantly lower than the total population, it is still a substantial figure—especially considering Gaza’s natural population growth rate (over 2% annually).[5] Therefore, a full population evacuation would require the use of IDF force, with all the strategic and moral implications this entails.[6]

Second, there is a logistical question about evacuating a population of two million people from the Gaza Strip. Egypt is likely to impose obstacles on exit through the Rafah Crossing; exit through crossings along the Israeli border is also complex; and maritime exit would require transferring Palestinians in small boats into the sea toward passenger ships. Exit crossings would become bottlenecks, creating conditions in which Hamas and other terrorist groups could attack Palestinians gathering near exit areas to deter them from leaving. Such scenes of terror would worsen Israel’s moral standing and inflame Arab public opinion in neighboring countries.

Third, it is unclear whether there are destination countries willing to absorb the Gaza population. Arab states have categorically rejected the possibility of taking in Palestinians. From the perspective of Arab leaderships, aiding in the evacuation of Palestinians from Gaza would be seen in Arab societies—and even by regime and military figures—as a betrayal of the Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim cause, and could seriously endanger their stability and survival. Muslim countries outside the Middle East, such as Albania and Indonesia—whose names surfaced as possible destinations—were quick to deny the reports and reject the option outright. Several European countries also expressed opposition to evacuating Palestinians from their homeland, viewing it as ethnic cleansing. Their opposition to absorbing Palestinians is also likely fueled by a strong current sentiment in Europe against immigration—especially from Muslim or developing countries. It is safe to assume that President Trump does not plan to accept Palestinians into the United States, given his anti-immigration policy. Thus, it appears that there are no Muslim or Western countries willing to absorb Gaza’s population—certainly not in large numbers. While it may be possible to find developing countries in regions like Africa willing to take in Palestinians in exchange for economic or political benefits, it is doubtful that Palestinians would voluntarily relocate to such places.

Under international law, the forced evacuation of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians against their will would be considered ethnic cleansing and a war crime. Since such an evacuation could only be carried out by the IDF, the implications for Israel’s future as a democratic state—and indeed for its very resilience and security—would be critical. Potential consequences of executing such a forced evacuation include: mass refusal of IDF soldiers to carry out the evacuation, reduced willingness of Israelis to enlist or remain in service, serious damage to peace treaties with Arab states—possibly even their cancellation—and the freezing of normalization talks with Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries; potential destabilization of moderate Arab regimes, including Jordan and Egypt; increased momentum for the Iranian axis and a resurgence of radical Sunni political Islam; a trigger for antisemitic incidents and possibly jihadist terror attacks across the Western world; and diplomatic isolation and legal sanctions against Israel by European countries and international institutions, leading to economic harm and disruption of academic and technological cooperation between Israel and Europe.

Even “voluntary emigration” of the population—under conditions where their livelihoods have been almost entirely destroyed and with active encouragement from Israel—is expected to be viewed by many international actors as ethnic cleansing and to provoke harsh political and legal reactions, alongside the potential destabilization of the region.

Alongside all of this, the feasibility of a “voluntary evacuation” of Gaza’s Palestinian population must also be evaluated in light of Gulf states’ pressure on the Trump administration. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar have all strongly opposed the evacuation plan, and each possesses significant economic, political, and geostrategic leverage over the United States in general—and over the Trump administration and its associates in particular.

In conclusion, it is clear that a reality in which most or all Palestinians “voluntarily emigrate” from Gaza would directly and significantly reduce the threat posed by the Strip. According to polls, a large majority of the Israeli public supports this.[7] However, the practical feasibility of this alternative is highly doubtful due to a range of weighty reasons. It carries historic implications for the moral character of the Jewish state and presents acute risks to Israel’s national security in arenas beyond Gaza—especially due to potential harm to peace agreements with Arab states, regional instability, the strengthening of radical Islam, and deterioration in relations with democratic Western countries. In any case, an analysis of this alternative’s practical viability indicates that “voluntary emigration” can, at most, accompany other alternatives—but it cannot stand on its own.

Alternative B: Occupation and Military Administration

The military administration alternative examined here includes the occupation of the Gaza Strip by the IDF, the imposition of a military administration, and maintaining control over the territory for an extended period. This option focuses on continuous clearing operations of Hamas infrastructure and operatives and other terrorist organizations (“mowing the grass”). From the perspective of Israeli interests, it would ideally be implemented without Israeli civil control, while Israeli civilian involvement would be limited to delivering essential humanitarian aid to prevent crises.

Occupying and holding the Strip could allow Israel to advance several objectives:

- Preventing Hamas from re-establishing itself or another extremist entity from gaining strength in the Strip;

- Demilitarizing the Strip—controlling its perimeter and maintaining military freedom to dismantle terror infrastructure;

- Providing civilian aid to Gaza’s residents and preventing humanitarian disaster and disease outbreaks;

- Preventing chaos in the form of takeovers by criminal and extremist elements;

- Leveraging influence to shape the area and reconstruct the Strip, and preparing the ground and conditions for transferring control to a selected governing body;

- Advancing de-radicalization efforts and neutralizing UNRWA;

- Preventing the spillover of negative effects from Gaza into the West Bank.

The occupation of the Strip and imposition of military administration could lead, after the dismantling of terror infrastructure, to a level of military stability that would enable the implementation of several follow-on strategies: establishing a moderate Palestinian government to replace Hamas (as part of a broader political settlement or independently), transferring control to foreign sovereignty (American, Egyptian, or other), annexation, or continued military occupation. In the shorter term, it could also lay the logistical groundwork for encouraging emigration—although it could not be described as “voluntary emigration” under the circumstances of Israeli occupation. This analysis refers to the possibility of military administration lasting several years.

Following the initial occupation, military activity would require a permanent IDF presence along the Strip’s inner borders and in corridors bisecting the territory, alongside forces conducting ongoing raids into the area, including underground. At a later stage (assuming successful suppression of most terror infrastructure), routine security activities could include security patrols and maintaining public order in populated areas. Dismantling Gaza’s terror infrastructure would require several years of intensive activity, followed by ongoing maintenance, similar to the pattern seen in the West Bank since Operation “Defensive Shield.” Former Defense Minister Gallant previously estimated that sustaining a military administration in Gaza would require four divisions, and he argued that the IDF does not have sufficient force capacity for this mission alongside its other tasks.[8]

Although under this alternative Israel has no interest in taking on civilian responsibility for the territory, that responsibility would still fall on its shoulders—even if other actors supply the population’s needs. International law defines the duties of the military commander in occupied territory: provision of public services, maintaining public order, and managing daily life, including: the supply of fuel for heating; healthcare, epidemic response, and sanitation; the supply of electricity; housing organization; waste and rubble removal; religious and burial services; education; employment; welfare; road infrastructure repair; firefighting and rescue services; population registry management; and the establishment of a law enforcement system: policing, investigation, arrests, prosecution, and incarceration. Over time, there would also be demands for non-essential public services such as culture, sports, community services, land management, urban planning and construction, agriculture, commerce and industry, import/export, environmental quality, as well as the establishment of a taxation and banking system.

The civilian responsibility that international law would formally place on Israel in this scenario would be further reinforced by the practical realities on the ground. In the absence of Hamas’s ability to enforce civil control, and given Israel’s opposition to local Palestinian rule, a vacuum would be created. If left unfilled, this could lead to chaos and humanitarian crises that Israel would be required to address as the de facto governing authority—and the only one capable of doing so. Independent efforts, or those encouraged by Israel, to establish municipal mechanisms that are supposedly apolitical and devoid of nationalist agenda—based on the “village associations” model—are expected to fail due to violence by Hamas, relying on its residual capabilities on the ground.

However, Israel might succeed in stabilizing humanitarian aid security operations via international private companies, such as the American firm currently involved in securing the Rafah Crossing.

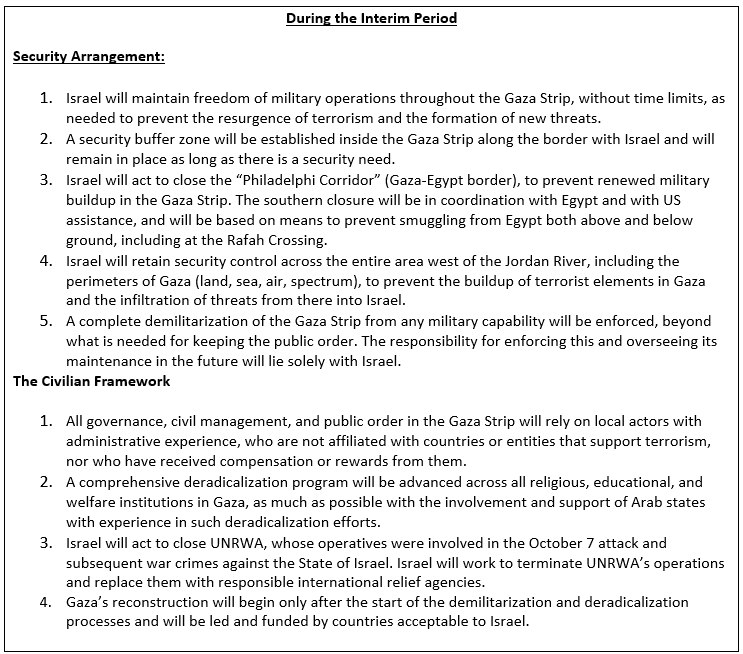

The problematic nature of a future reality based on the concept of ongoing military occupation is illustrated by a proposal (see Figure 2) published in December 2023 by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs (JCPA) and the Bitachonistim (“Security Experts”) non-profit organization.[9] According to the proposal, at the end of the military phase dismantling Hamas’s rule and military infrastructure in Gaza, Israel would establish a military and civil administration in the territory—implicitly for an indefinite period.

Figure 2.

The proposal opposes a unified Palestinian rule in the Strip, particularly by the PA, on the grounds that it is committed to the narrative of resistance against Israel, is corrupt, and too weak to effectively govern. Instead, the proposal calls for decentralization and fragmentation of the governing system in Gaza into five local administrations (aligned with Gaza’s five districts). These local administrations would be responsible for civilian governance and promoting deradicalization in the education system and government structures. An international authority would assist in advancing these processes as well as in reconstructing infrastructure and the economy in the Strip.

This proposal, similar to the “day after” vision presented by Prime Minister Netanyahu shortly after its publication, does not explain how the vital enlistment of Arab states in support of Gaza’s reconstruction and deradicalization processes can be achieved without granting the Palestinians a political horizon. Ultimately, responsibility is expected to fall on Israel’s shoulders—both in civilian aspects and in matters of public order and internal security—with all the significant military, economic, and legal-political costs this entails.

According to publicly available security estimates, the cost of maintaining a military occupation of the Gaza Strip is estimated at approximately NIS 25 billion annually. Around NIS 20 billion would go toward military operations in the Strip, reservist service, and other military expenses. An additional NIS 5–10 billion per year is estimated as the cost of operating a civil administration mechanism and providing basic civilian services to Gaza’s Palestinian population. It should also be noted that prior to Israel’s disengagement from Gaza in 2005, a significant portion of the budget for managing the area came from local economic revenues and taxes, which, given the current devastation in Gaza, can no longer be relied upon as the source of income for funding the costs of the military administration.[10]

As the occupying force in the Gaza Strip, Israel would be perceived as fully responsible for the area, including its civilian affairs. Legally, it is likely that maintaining a continued military occupation, in and of itself, would not impose significantly greater costs on Israel than the current situation in the West Bank. However, under such a reality, Arab states (and even more so, international actors) would likely refuse to invest heavily in Gaza’s rehabilitation. Without such civilian reconstruction, prolonged humanitarian crises may develop, reflecting negatively on Israel and potentially inciting further radicalization among the Palestinian population.

Furthermore, a situation of ongoing military conflict between Israel and resistance elements in Gaza could negatively impact relations with Egypt—ranging from potential terrorist spillover and refugee movement into the Sinai Peninsula to Egyptian demands to alter agreements with Israel. Other Arab states would likely view this scenario as harmful and a source of instability, especially if it includes renewed Jewish settlement in the Gaza Strip. In addition, continued pursuit of the military occupation alternative could hinder normalization efforts with Saudi Arabia, whose broader strategic vision is the resolution of the Arab–Israeli conflict and the creation of a regional alliance to strengthen Israel’s national security.

The analysis reveals advantages to the military occupation option—but only if it is part of a broader strategy of Gaza’s civilian reconstruction and stabilization, and if it concludes within a relatively short timeframe, in a context where there are no Israeli settlements in the Strip and a relevant actor can assume governance. The military administration would provide full security control and extensive intelligence access on the ground, leading to severe blows against Hamas, the dismantling of terror infrastructure, and the ongoing elimination of security threats emanating from Gaza; it would sever Hamas’s control over the population and the resources of the Strip. A military administration would allow Israel to supervise the deradicalization of education and civil life; and it would facilitate reorganization of the humanitarian aid system—including pushing out UNRWA, which sustains the refugee narrative and collaborates with Hamas. Additionally, the direct financial costs to Israel are expected to be manageable, as are the political-legal consequences.

However, if the military occupation alternative is viewed as a long-term, standalone strategy, its costs will become extremely burdensome. First, regardless of military success, it will not eliminate Hamas—as evidenced in the West Bank and the long history of Israeli control over Gaza since its capture in 1967. Hamas’s deep roots in Gaza will not disappear, especially in the absence of foundational efforts to foster a political and ideological alternative. Military occupation will preserve the resistance narrative, whether through Hamas or other platforms.

Moreover, continued occupation would impose escalating military and economic costs on Israel at a particularly difficult time. Maintaining the occupation would require large military forces, reducing Israel’s ability to manage risks in other sensitive arenas; it would place full responsibility for Gaza’s civilian governance on Israel, with all the political complexities and financial burdens that entails; it would erode Israel’s strategic relations with Arab states and freeze normalization with Saudi Arabia, which is intended to form a moderate regional alliance against Iran and radical Sunni Islam; it would attract strong international pressure and place full blame on Israel for the situation; and it would inflict major economic damage on Israel—especially at a time when the economy is recovering from war-related expenses and facing a global climate of uncertainty, marked by rising protectionism and trade wars.

Alternative C: Continuation of the Current Situation (Postponing Decisions)

This alternative refers to a reality in which Israel does not maintain a presence or at least extensive military activity in the Gaza Strip, and at the same time refrains from promoting political initiatives to remove Hamas from power. In the short term, this is the option that would allow the implementation of the outline for the release of the hostages and the postponement of wide-ranging military and political moves to eliminate Hamas. In this alternative, Israel’s activity would be limited in the civil sphere to controlling the amount of humanitarian aid entering the Strip (without monitoring it and without having responsibility for its distribution), and in the military sphere, would be satisfied with pinpoint actions to neutralize threats, and from time to time increase military activity as a preemptive measure or in response to terrorist acts originating from the Gaza Strip.

This alternative is based on a strategy of emergent behavior, adapting to the changing reality and attempting to exploit it for Israel’s needs, rather than trying to shape it. Currently, this is not an official policy of the State of Israel, and it is difficult to assume that at any point in the foreseeable future, Israel will decide to adopt it officially. However, it is a realistic alternative, stemming from a dynamic in which Israel refrains from advancing military or political initiatives in the Gaza Strip or fails to implement the initiatives it tries to promote.

Several scenarios could lead to this problematic reality, including Israeli adherence to the “voluntary emigration” alternative without successfully implementing it; American pressure to avoid occupying the Strip for political reasons; or a temporary military occupation without attempting—or failing—to establish an alternative Palestinian government. The development of such a reality could also be influenced by external factors, such as the willingness of Arab states to intervene in the Strip to stabilize and rebuild it; renewed fighting in the north against Hezbollah; an attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities; or internal political crises in Israel that divert attention from stabilizing the Strip.