Publications

INSS Insight No. 1533, November 11, 2021

Israel has an interest in preventing illegal exploitation of Palestinians working in the country, in order to support stability in the West Bank, fight the shadow economy in Israel, and uphold the law. The Israeli reform in the work permit regime in December 2020-March 2021 aimed to eliminate the illegal trade in work permits of Palestinians employed in Israel by strengthening workers’ bargaining power. This article presents a preliminary evaluation of the impact of the reform. It shows that in the first seven month of its implementation, the reform neither resulted in the reduction of the scale of the permit trade, nor the associated permit prices. The article also proposes policy recommendations: improving and enhancing the use of the new app that matches workers and employers without the mediation of brokers; enforcing the prohibition of the permit trade in Israel through sound punitive measures; and coordinating with the Palestinian Authority regarding enforcement against Palestinian permit brokers.

Many West Bank Palestinian workers seek employment in the Israeli economy, as wages in Israel are much higher relative to wages in the Palestinian economy. Given that the quota of work permits is lower than the number of potential workers, some are propelled to choose between working without a permit and purchasing a permit via a broker. This grim situation is depicted in a few reports (Kav La-Oved, 2019; Bank of Israel, 2019, pp. 79-95; ILO, 2020 & 2021; State Comptroller, 2020).

These black market transactions are possible because work permits are requested by Israeli sponsors for specific workers, and until the implementation of a recent reform, permits were fully controlled by the employers or sponsors. Permit brokers, usually Palestinians operating in the West Bank, can connect workers with sponsors at a cost paid by workers. Roughly 75 percent of such paying workers reported in recent surveys that they used the permit to enter Israel, and were then employed by an employer other than the sponsor.

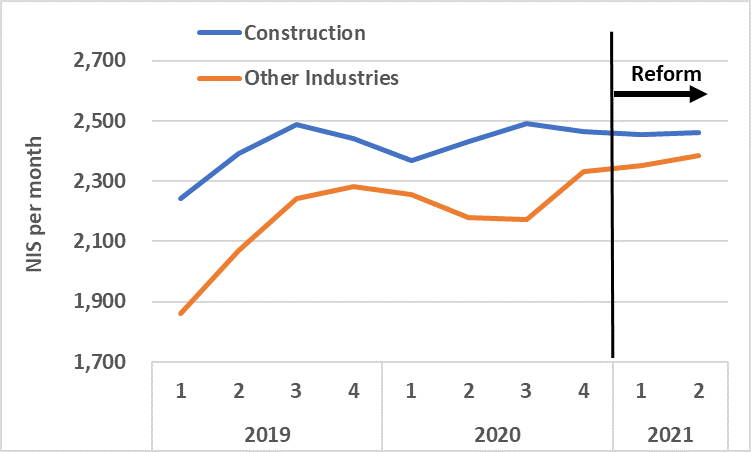

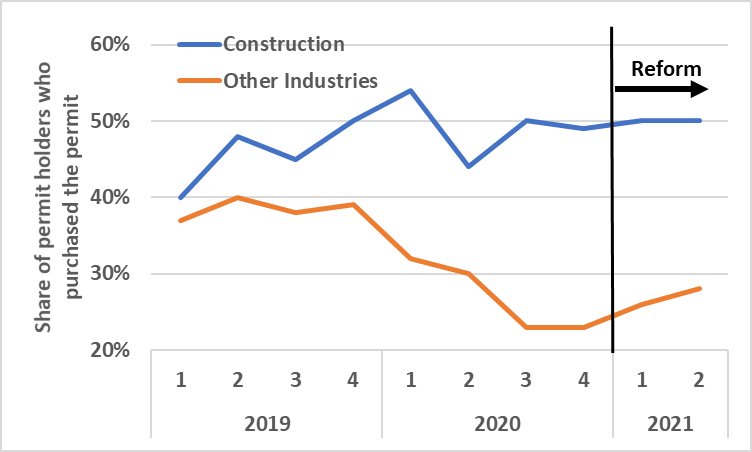

This situation generated a lucrative permit trade. In 2019, about 43,000 workers purchased work permits for about NIS 2,300 per month. The revenues in 2019 totaled NIS 1.2 billion, and the ILO estimated the profits of the permit trade net of employers’ expenses (social security, pension, etc.) at NIS 427 million (ILO, 2020, p. 23). The illicit permit trade declined by about 40 percent with the lockdown imposed following the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 Q2, but recovered during the second half of 2020. Hence, in 2020 about 40,000 workers purchased work permits for NIS 2,440/month, and the revenues totaled NIS 1 billion (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: Permit price by industry, 2019-21 | Source: Palestinian Labor Force Surveys

Figure 2: The share of permit purchasing workers by industry by percent, 2019-21 | Source: Palestinian Labor Force Surveys

As selling permits is illegal in Israel, permit brokers offer to sell permits – typically openly – in the West Bank. Many permit brokers advertise on social networks with offers of various types of permits, and some have offices on main streets (Figure 3). In addition, about a fifth of the workers who purchase a permit sign an agreement with the broker or hand him a promissory note. The open sale of permits in the West Bank and use of formal legal documents in the sale indicate that both permit brokers and workers do not perceive these transactions as illegal, although it is not clear to us whether these transactions are technically prohibited by Palestinian law.

Figure 3: Permits to enter Israel for sale, Qalqilya, September 2021 (sign reads: Qalqilya’s office for services … Entry permits to Israel of all types) | Credit: Kerem Navot

Reforming the Permit Regime

In recent decades, the legal, official work permit regime was based on the administrative allocation of quota of permits to Israeli sponsors in certain industries such as construction and agriculture. Sponsors were able to request work permits for specific Palestinian workers and commit to employ them. To the extent the sponsor was not satisfied with the worker for any reason, he could revoke the worker’s permit and use the same quota to request a permit for an alternative worker. This institutional set-up bestowed much of the bargaining power on Israeli employers or their Palestinian partners who broker the permit trade and kept workers vulnerable.

In December 2016, the Israeli government (Decision 2174) decided to reform the permit regime in the construction and manufacturing industries. The reform canceled the employer specific quota, and instead moved the control of the quota to veteran workers who are either employed or separated from their employers – in the past 60 days for construction workers or 14 days for manufacturing workers. These veteran workers who are eligible for a permit can contact any registered employer and negotiate new terms of employment. Clearly, this reform aims to strengthen the bargaining power of the Palestinian workers at the expense of employers and permit brokers.

The implementation of the reform in the construction industry was announced in December 2020, and in the manufacturing and services industries in March 2021. The launch of the reform was publicized by the Israeli authorities, but a small-scale survey by Kav La-Oved (2021) suggests that most workers heard about the reform from other workers. The reform was also discussed in Facebook worker groups. While some workers welcomed the reform, hoping for the “demise of the leeches sucking the workers’ blood,” others were more skeptical about the benefits of the reform for workers.

Impact of the Permit Reform

The preliminary evaluation of the reform is based on administrative data on the use of permits and the quota, and the Palestinian Labor Force Survey.

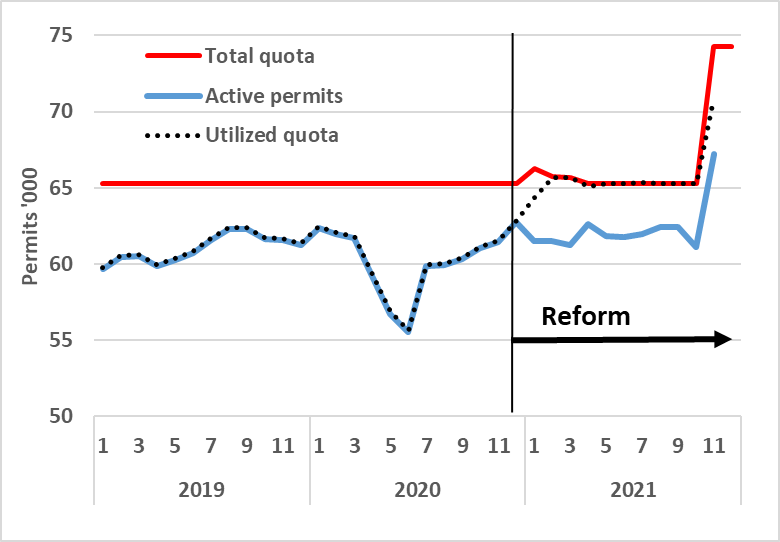

The immediate impact of the December 2020 reform in the construction industry is noticed in the administrative data (Figure 4): by March 2021, the number of utilized quota (black dotted line) increased to the maximum (red line), as the control of the quota moved from the employers to veteran workers. Yet despite the full utilization of the quota, the number of active permits (blue line) reflecting registered employment relations did not increase. Thus, the control of unused permits switched from employers to workers, but formal employment did not increase.

Figure 4: Total and Utilized Quota and Active Permits in the Construction Industry, 2019-21 | Source: Civil Administration

In fact, as the result of the reform, the workers can be categorized according to three groups:

- Workers with active permits

- Veteran workers who control a quota and can have a permit when matched with an employer

- Workers who don’t have a quota.

The distinction between the last two groups is reflected in sales ads offering permits only to “quota owners,” and in the search of workers without quotas for vacant quota to secure a permit. The increase in the quota permits from 65,000 to 74,000 in late October 2021 relieves the stress of the workers without quota, and allows some of them to get a permit.

The Labor Force Surveys for 2021:Q1-Q2 indicate that the greater bargaining power of veteran workers did not yet affect the permit trade – neither the share of workers purchasing permits from permit holders nor permit prices declined during the first half of 2021 (Figures 1 & 2). A Kav La-Oved survey also indicated that the permit trade continued after the reform as well as the numerous permit ads on social networks.

The lack of change in the permit trade and permit prices, together with the administrative data indicating the same level of active permits (Figure 4), suggests that the markets have not responded yet to the reform. One plausible reason is search frictions, or the difficulty of workers and employers to find each other. Aiming at enhancing the operation of the market for Israeli employers and Palestinian workers without involvement of brokers, the Israeli authorities launched a smart phone app aimed at facilitating employer-worker matches. As of late October 2021, about 10,000 workers joined the database, and only employers can contact registered workers. Interestingly, since the launch of the app, permit brokers note that the immediacy of the transaction – often within 10 minutes of the request of the permit – indicating that they have undesirable direct or indirect access to the app.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Israel has an interest in preventing illegal exploitation of Palestinian workers, in order to support political stability in the West Bank, fight the shadow economy, uphold and the law, and fulfill the country’s commitment to protect worker rights. Combating the permit trade is a process that began with a positive reform aiming to strengthen the workers’ bargaining power. Yet by mid-2021 the illegal permit market had not shrunk, and the permit price had not declined. Policy recommendations below focus on enhancing the operation of the formal employment market, while undermining the permit trade.

The formal employment market is undermined by the difficulties to match suitable employers and workers. The launch of the matching app in the last few months is an important step in this direction. We recommend publicizing the availability of the app among workers and enabling workers to contact employers via the app.

Additional steps can be taken to undermine the illegal permit trade, with Israeli criminal, economic, and administrative enforcement against employers who request the permits sold by the brokers. Enforcement against Palestinian permit brokers – as the Palestinian cabinet decided on October 2019 – is also critical in undermining the permit trade. Moreover, public trading of permits and the use of agreements and promissory notes suggest that Palestinians are not concerned with the (il)legality of the permit trade. Israel can also undermine the permit brokers by restricting their access to the new matching app.

As the permit trade takes place in both Israeli and Palestinian jurisdictions, the ILO (2021) is correct that “effectively addressing these issues…will require dialogue and coordination between the two sides.”