Publications

INSS Insight No. 1617, July 12, 2022

The recent air attacks in Syria are attributed to Israel, the regional prestige of the Assad regime is on the rise, and Israel-Russia relations are growing tense. This backdrop invites a debate on the continued validity of Israel’s “campaign between wars” policy in Syria. The article concludes that Israel should develop a multidimensional plan against the threat on the northern front, in which the air attacks will be one element of a comprehensive campaign.

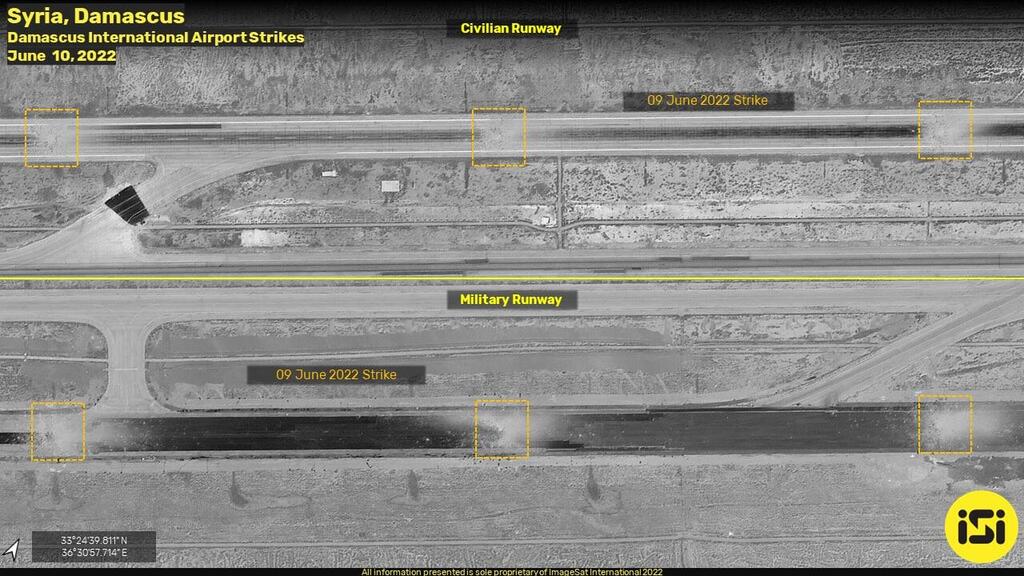

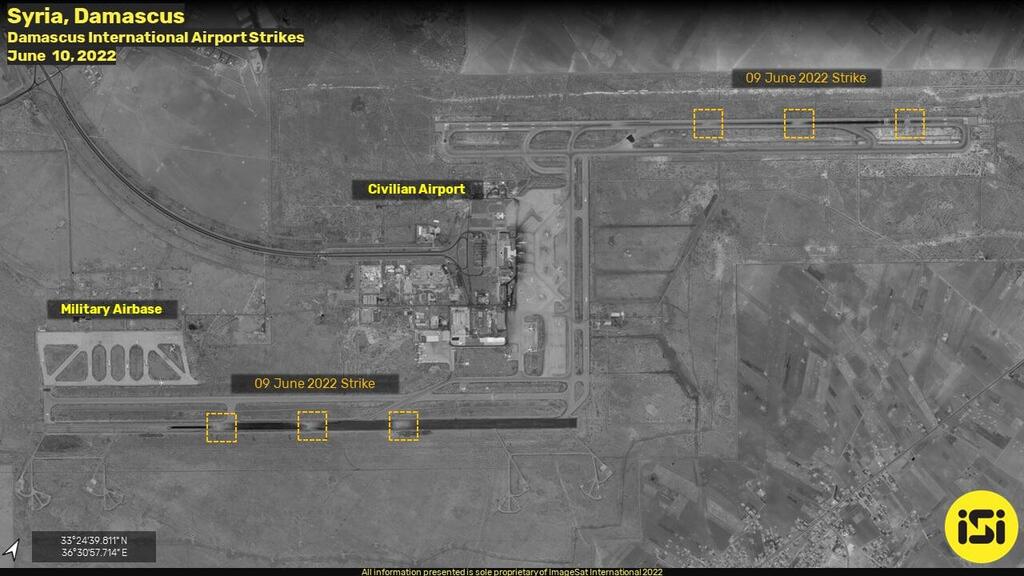

The recent air attacks in Syria, attributed to Israel, represent a major element in the Israeli strategy on the northern front. These attacks are designed to serve three principal purposes: prevent a military buildup by Hezbollah and other Iranian proxies by disrupting the transfer of strategic weapons to the organization; damage the infrastructure of the Shiite proxies in southern Syria, which are deployed for opening a front against Israel; and wage a long-term effort to drive a wedge between Damascus and Tehran (an objective defined by the Israeli security establishment). Presumably over the years of warfare, Israel has also taken action beyond the “campaign between wars” (CBW) through a number of more covert channels, including special operations and cognitive operations. In recent years, however, it appears that the CBW has become the principal tool. Ostensibly, two recent attacks in Syria, on June 10, 2022 on Damascus International Airport and on July 2, 2022 against targets close to the city of Tartus, are a continuation of the CBW approach. However, the criticism they aroused and their potential ramifications mandate a reconsideration of the validity and utility of this approach.

The campaign between wars has scored much success over the years. The vision of Iranian entrenchment in Syria, as conceived by al-Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani (killed in early 2020), has not materialized on the desired scale. Since then, this entrenchment has been visibly scaled back in pace and scope. The al-Quds Force remains without an organized plan in Syria, and the CBW has contributed to this, with the number of attacks in this framework believed to be in the hundreds. Over the past five years, Israel has caused extensive damage to attempted weapons transfers, including precision weapon components sent from Tehran to Syria, and sometimes also to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

The CBW also plays an important role that goes beyond the Syrian theater. Years of pinpoint attacks against Iranian targets have made the Israeli military the key, if not the only player taking action against Iranian subversion throughout the Middle East. This fact has bolstered Israel's regional status, and has made it a potential partner for the Gulf states and other Sunni countries in the struggle against the common enemy – Iran.

Despite the success of the CBW, current circumstances require the recognition of its limitations. While the Iranian force in southern Syria is visibly stagnating as a result of the CBW and the winding down of the Syrian civil war, this does not mean that Hezbollah and the prominent role that it plays in the area have declined. As of now, the primary emphasis in the Iranian entrenchment model is preserving the power and status of Hezbollah in the south and interior of Syria. In the south, close to the border with Israel, Iran relies mainly on Hezbollah, Syrian army units subject to its influence (among them the 4th Division, commanded by Maher al-Assad), and local defense militias, which it equips and trains. Two important Hezbollah groups are the Southern Command, which integrates Hezbollah officers as advisers and supervisors in the Syrian army ranks, and the Golan File unit under direct Hezbollah command, which establishes terrorist cells comprising primarily local Syrians. Hezbollah has had to pay the price exacted by the CBW, and pressure from the Syrian regime has sometimes forced it to reduce its activity, but its power remains substantial, and it is clear that Iran does not intend to forego the role it plays in Syria.

The CBW has been far less successful in driving a wedge between Iran and Syria. There appear to be measured and tactical changes, rather than a strategic change in the relations between Tehran and Damascus. Bashar al-Assad, who seeks to establish his regime's sovereignty in Syrian territory, occasionally imposes restrictions on the Iranians, among them reduced freedom of movement at the border crossings, constraints on smuggling of goods to Syria that damage the Syrian economy, and a ban on attacking Israel from Syrian territory. It was also reported that Assad had previously barred Iran from transferring arms through the Damascus airport, but the attack on the airport in June, however, indicates that the Iranians are not strictly complying with the Syrian president's orders. At the same time, it is doubtful whether Assad genuinely wants to limit Iranian activity, since he owes his survival to Tehran. If the CBW does propel Assad to expel the Iranian presence from Syria, or at least impose limits on it, years of deep Iranian entrenchment in the state institutions and agencies, civil infrastructure, and economic and social projects will make it very difficult for him to achieve this objective.

It could be argued that the Israeli attacks have also failed to provide a solution for Iran's long-term civilian entrenchment in Syria. Beyond generating influence and disseminating Shiite Islam, this entrenchment was designed to support Iran's military ambitions in Syria in particular, and in the entire region in general. Furthermore, the air attacks in Syria are a drop in the bucket. The IDF has disrupted the shipments of weapons and Iranian entrenchment to some extent, but has not halted it completely. Quite a few weapons shipments have avoided detection by the Israeli Air Force.

Beyond limitations in the operational achievement, the CBW in general, and the attacks on Damascus Airport and Tartus in particular, have aroused additional questions about the degree of legitimacy that Israeli has enjoyed up until now in this context. In line with its usual practice, Russia severely condemned the recent actions, and the Russian Foreign Ministry stated that Israel must halt what it describes as the "vicious practice" of attacking civilian infrastructure. As in earlier incidents, the Israeli ambassador in Russia was summoned for clarifications, but for the first time, Russia submitted a UN Security Council resolution that included condemnation of the attacks and a warning against destabilizing Syria and violating its sovereignty. These measures suggest that Israeli attacks are liable to result in even sharper responses from Moscow, which in any case wishes to demonstrate its power in the Middle East in order to offset its weakness in Europe. Further evidence of this was the message sent this past May by the use of Russia's S-300 against an Israeli air force plane. Although attacks against Iranian targets in Syria to some extent serve Russian interests, as Moscow is competing against Iran for influence in the area, when these attacks damage targets of the Syrian regime, as they inevitably do, Russian pressure on Israel is liable to become even heavier.

In addition, in recent months Assad has consolidated his regional standing as leader of Syria, and Jordan, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain have normalized their relations with him and embraced him as part of the Arab world. This trend, parallel to these countries' normalization process with Israel, is liable to exert pressure on Jerusalem to scale back its attacks, especially against the regime's ostensibly civilian infrastructure, which undermine Syria's sovereignty and stability.

A no less important question is to what extent Israel can try Iranian patience by persisting in operations against it in Syria, and according to foreign reports, also in more remote theaters. Assad is still weak, and is therefore not expected to respond at the present time. However, the possibility of a more vigorous Iranian response than it has undertaken to date, in order to "restore the balance of deterrence," as stated by Tehran, cannot be discounted. Such a decision would indeed deviate from the Iranian policy of restraint, which recognizes Israel's advantage in a conflict with Iran, and would also ignore Assad's "demand" that Iran refrain from attacking Israel from his territory. Yet in light of Israel's mounting attacks, Iran is nevertheless liable to take the risk of responding.

This is therefore the time to reexamine and improve the Israeli strategy in Syria by developing a multidimensional plan against the threats to Israel on this front, while addressing the following issues: the correct balance between attacks against Syrian targets and attacks against Iranian targets; preservation of the strategic coordination with Russia, given the consequences of the war in Ukraine; the campaign’s end state, i.e., whether there is a measure for assessing the achievement; and the price that Israel will be willing to pay for continuation of the CBW – and what will constitute grounds for escalation.

In addition to the air attacks and their adaptation to the current circumstances, Israel should develop a campaign that integrates all of the security and political establishment entities and their various capabilities. This framework can include a large-scale cognitive campaign that will highlight the threat of Iranian subversion in the international community and take action to reduce it. It is also useful to improve operational capabilities in Syria, while utilizing the security establishment's covert tools in order to streamline Israel's selection of strategic and operational targets in the theater for which the CBW provides a partial solution (such as driving a wedge between Syria and Iran, Iranian civilian entrenchment). Another potential means of exerting influence is instituting relations with local communities in the area opposed to the Assad regime and Iranian influence. This applies mainly to Sunni and Druze groups, which are eager for dialogue with Israel and its support. Strengthening the connection with them can be expressed, inter alia, in humanitarian aid, and is likely to reduce the dependence of the local population on Hezbollah and Iran, which are taking full advantage of the civilian distress. At the regional level, Israel should step up its cooperation with its new friends in the Gulf in order to diminish Iranian influence in Syria and other theaters in the area.

Overall, in such a tangled and complex theater of conflict as Syria, where Iran is spearheading military, economic, and civil efforts to create an advantage for itself, Israel should also employ diverse tools – both military and civilian.

The advocates in Israel of revising the Israeli strategy in Syria are not new or external to the security establishment. It appears, however, that the establishment's current leading paradigm is that Syria is a "solved” theater, and that the campaign between wars provides an adequate solution to the challenges that it poses. The relative comfort that the air attacks have facilitated until now is not only fragile and temporary, but liable to lead to conceptual stagnation and reduced investment of resources in long-term solutions. The current situation heightens the need for innovative thought, and the sooner this begins, the better.