Publications

INSS Insight No. 1726, May 24, 2023

The results of Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary elections on May 14, 2023, were a major success for the incumbent, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and a bitter disappointment for the opposition. The fact that Erdogan led after the first round of voting, coupled with the momentum that his electoral success gave him, positions the opposition camp on an uphill battle, and increases the chances that Erdogan will triumph in the second round and earn another term of office as president. Given the probability that the election will end with Erdogan’s being sworn in again as president, it is unlikely there will be significant changes in Ankara’s domestic or foreign policy.

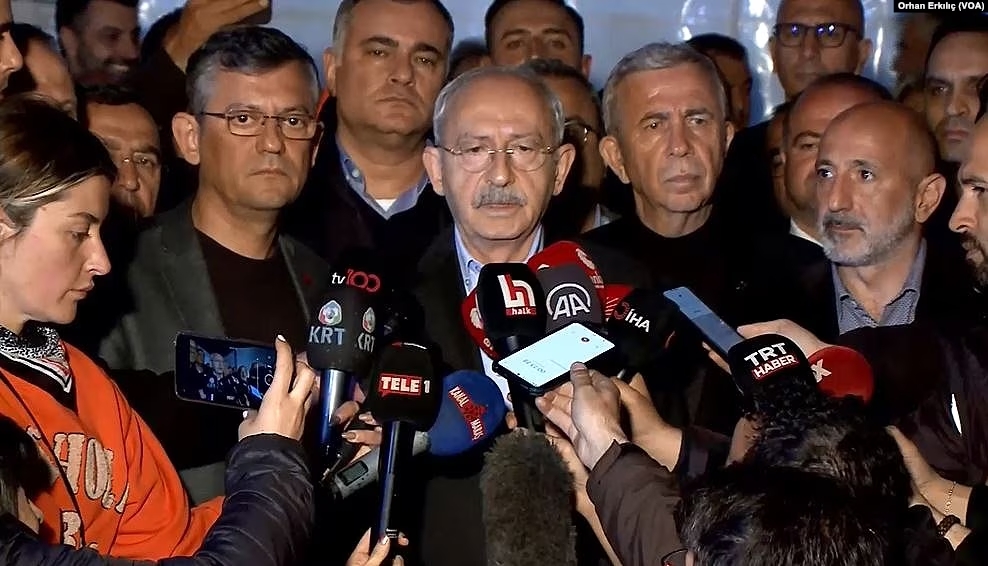

In the Turkish presidential elections on May 14, 2023, incumbent Recep Tayyip Erdogan was the big winner, while the opposition suffered a major disappointment. According to many pre-election polls, opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu, who headed an alliance of six parties opposed to Erdogan, known as the “Table of Six,” was in the lead – and according to some polls was even poised to emerge victorious from the first round of voting. According to these polls, the “Table of Six,” with the addition of the bloc led by the pro-Kurdish party, was also expected to garner a majority in parliament. The results, however, painted a very different picture. President Erdogan won 49.5 percent of the votes – a hair’s breadth away from the 50 percent needed for a victory after the first round – and significantly ahead of Kilicdaroglu, who won 44.9 percent of the votes. In addition, the parties that support Erdogan won a majority in parliament. At the same time, however, Erdogan did not manage to secure an outright victory after the first round of voting; he received fewer votes than in the previous election, and saw the coalition’s parliamentary majority dwindle. The setback that opposition parties suffered when the elections results were announced, coupled with the renewed momentum that Erdogan now enjoys, and the fact that the third presidential candidate (which received 5.2 percent of the votes) has endorsed Erdogan, increases the chance that the incumbent president will win the second round of voting on May 28, and even expand his advantage over Kilicdaroglu.

A victory for Erdogan would be another indication of how profoundly identity politics has influenced Turkish society. The opposition tried to frame the political struggle in the country as a struggle for Turkish democracy and a revival of the economy, and promised voters that better times lay ahead. In contrast, Erdogan employed a religious and nationalistic narrative: he portrayed Kilicdaroglu as supported by Kurdish terrorism and the West, and as a danger to conservative values; he also issued many homophobic statements. The President highlighted Kilicdaroglu’s religious identity – Alevi, and not Sunni – and used that to portray him as a threat to Islam in Turkey. Apparently most Turkish voters, especially those outside the large cities, were more receptive to Erdogan’s threats than to Kilicdaroglu’s promises, and responded more to calls to “defend” the identity of Turkey than to pledges to put an end to daily hardships. Erdogan garnered most votes even in the regions affected by February’s devastating earthquake. The importance of identity politics in Turkey also manifests itself in the fact that the nationalist parties, those that support Erdogan as well as those who oppose him, were successful in the election.

This situation could lead to increased tensions among the opposition ranks. Kilicdaroglu forced his nomination as the opposition’s candidate, despite objections from large parts of the bloc’s supporters. He could face harsh criticism from members of his alliance, who will attribute their loss to his stubborn insistence on being the candidate, instead of more popular options. Similarly, the idea of the “Table of Six” – which was based on unanimity between the partners, and gave influence to small parties that do not have a real voter base – delayed the process of finalizing an election platform and even selecting a candidate, which allowed Erdogan to enjoy the political limelight alone for several months. Finally, the opposition’s attempt to rely on support from the Kurds, without allowing the pro-Kurdish party to become an official member of the bloc, proved to be a failure, especially given Erdogan’s counter-campaign, which highlighted nationalist sentiments in Turkey and which, it seems, resonated with the views of many Turkish voters.

As with previous election campaigns, the voter turnout was high – 89 percent – which highlights the political involvement of Turkish citizens (voting is mandatory in the country but is not enforced). However, the opposition and a number of international organizations accused the Supreme Election Council of not sharing sufficient information and of lacking transparency, and tallies were challenged in a number of locations. Similarly, the campaign was characterized by blatant inequality and preferential treatment toward the incumbent, especially in the media, most of which is owned by the state or by people closely associated with the President and which gave far more coverage to Erdogan than to his rivals. Moreover, the election took place in the shadow of judicial processes that were launched primarily against the pro-Kurdish party and its leaders, as well as against the mayor of Istanbul, who is a key and popular member of the “Table of Six.” All this in a country where the judicial system enjoys extremely limited independence.

In many ways, an Erdogan victory in the second round of the presidential election would spell a degree of continuity for Turkey. The Turkish President will have earned proof that he can compensate for economic difficulties with a conservative, populist narrative, which has ensured the extension of his rule. Thanks to the renewed legitimacy and at a time when the opposition is likely to become embroiled in internecine squabbles, he will enjoy greater room for maneuver – which could encourage him to deploy even more repressive measures against his rivals. At the same time, Turkey is on the brink of economic collapse. Over the next few months, the President will have to make some tough decisions; if he does not, the country will descend into an economic tailspin. Given the success of his nationalistic rhetoric during the election campaign, the President will likely try to divert the public’s attention away from the economy by being more active on the foreign policy front.

In terms of foreign policy, another term of office for Erdogan as President does not auger well for relations between Turkey and the United States and the European Union. During the campaign, Erdogan even accused US President Biden of supporting Kilicdaroglu. This is a direct continuation of previous allegations, primarily coming from Turkish Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu, that the United States was among those who supported the failed coup attempt in July 2016. Turkish objections to Sweden joining NATO are likely to return to the agenda in the near future; it will be a key issue of the NATO summit scheduled to take place in July in Lithuania. Turkey’s allies in NATO (apart from Hungary) are keen to advance Sweden’s membership of NATO at the upcoming summit, and failure to do so is likely to cast a shadow over the summit in the context of the war in Ukraine. Turkey is demanding that Sweden extradite individuals whom it suspects were involved in terror on behalf of the Kurdish movement or the Gulenist movement (the organization that Ankara has named as the main instigator of the attempted coup, among other accusations). On the other hand, Sweden argues that it cannot acquiesce to Turkish demands, since the suspects are Swedish citizens and there is not enough substance behind the allegations against them. At the same time, Ankara would be far more willing to advance the issue of Swedish membership of NATO if the US Congress agrees to sell it F-16 fighter planes.

Beyond the tension that exists between Turkey and the other members of NATO, it was clear in advance of the elections that Russia prefers to see Erdogan in office, rather than Kilicdaroglu, and Russia’s position contributes to Ankara’s unwillingness to sever ties with Moscow over the war in Ukraine. President Vladimir Putin has helped Erdogan in many ways. He allowed Turkey to postpone payment for the purchase of Russian gas to ease pressure on the Turkish lira, which has been severely depreciated since 2018. As part of Erdogan’s election campaign, Putin participated remotely in the ceremony surrounding the arrival of the nuclear fuel to the first nuclear power plant in Turkey, that is being built and will be operated by a Russian governmental firm, Rosatom. Similarly, Moscow pressured Syrian President Bashar Assad to open a dialogue with Turkey to normalize bilateral relations, which would allow Erdogan to present the Turkish people with an achievement concerning the 3.7 million Syrian refugees on Turkish territory – refugees that most Turkish citizens want to see return to their homeland. Kilicdaroglu even accused Russia of interfering in the Turkish elections – accusations that Erdogan publicly repudiated.

Regarding Turkish policy in the Middle East, Erdogan will presumably be keen to continue with the processes of normalization that he has advanced over the past two years – with the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Egypt, and Syria. The severe economic crisis in Turkey has forced Ankara to seek investment from the Gulf states, but it seems likely that any such investment would depend on Turkey adopting more responsible monetary policies, some of which Erdogan rejected – at least before the elections – including a rise in interest rates. The principal winner from another term of office for Erdogan is Qatar, which sees support from Turkey – support that is based, inter alia, on the ideological similarities between Erdogan and the Qatari regime, and which even manifests itself in the existence of a Turkish military base on Qatari soil – as one of the guarantors of its independence.

Relations between Israel and Turkey are enjoying the fruits of the agreement to normalize bilateral ties that was inked in August 2022, following a process that Erdogan himself spearheaded. In the aftermath of the earthquake, Israel sent one of the largest foreign aid delegations to Turkey, and 2022 also marked a record year for bilateral trade between the two countries – $8 billion (compared to the previous record of $6.7 billion in 2021). In the tourism industry, 2022 also saw a record number of Israelis visiting Turkey: 800,000, compared to 570,000 in 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic). At the same time, the disputes between Israel and Turkey over the Palestinian issue, especially the Gaza Strip and Jerusalem, are still profound, and it is safe to assume that the issue of Hamas activists residing in Turkey and planning terror attacks in the West Bank from there remains a major source of tension. Israeli-Turkish relations was a marginal issue in the election campaigns of both political blocs, but it is clear that hostility toward Israel in Turkish public opinion is widespread among supporters of both Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu. These relations could also be undermined if there is a crisis between Ankara and Washington, partly over the issue of Swedish membership in NATO. Moreover, the continued tension between the Biden administration and the Netanyahu government is deemed a sign of Israeli weakness, which could serve Erdogan in the future if there is a significant escalation on the Israeli-Palestinian front.