Publications

Strategic Survey for Israel 2019-2020, The Institute for National Security Studies, January 2020

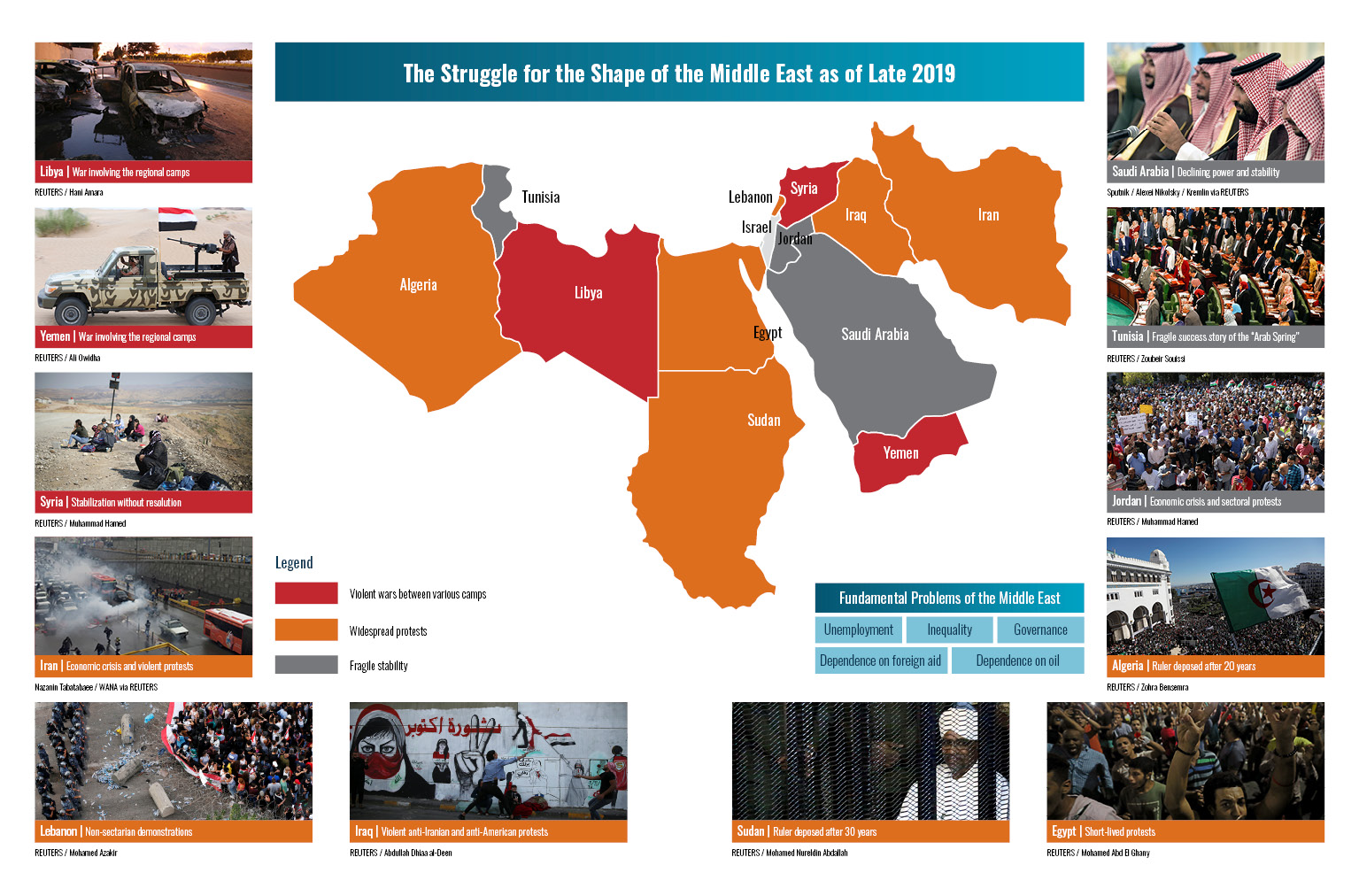

Nine years after the dramatic events of late 2010 and early 2011 (the so-called Arab Spring), the regional upheaval persists and the Middle East continues to be characterized by instability, uncertainty, and volatility. There is broad consensus among researchers and observers that the region is mired in a deep crisis, while undergoing processes with crucial long term implications and engaged in a turbulent contest over its character.

This struggle is unfolding in two realms: first, between four main camps competing over ideas, power, influence, and survival to define the contours of the regional order; and second, between rulers and publics within the individual states, most of which continue to suffer from basic social and economic problems that have only worsened since the “Spring.”

The Struggle over the Regional Order

The first level of this broader struggle over the shape of the Middle East is the contest between four clusters of actors wishing to see a regional order emerge that will reflect their interests on a variety of core issues: Iranian influence, relations with the West, territorial integrity of states, political Islam, sectarianism, and modes of governance. The four camps are:

* The radical Shiite axis: This cluster is led by Iran and includes Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, Hezbollah, the Houthis in Yemen, the Shiite militias operating in various arenas throughout the Middle East, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (despite its Sunni identity). Of the four camps, this one is the most organized and cohesive. It enjoys various means of political, economic, and military leverage, operates in multiple theaters, and is progressing in its efforts to create a revisionist, pro-Iranian, and anti- Western regional order.

* The pragmatic Sunni states: This bloc includes Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the other Arab Gulf states (except Qatar). These actors, with their authoritarian governing structures, are advancing a pro-Western, anti-Iranian, anti-Islamist, and nationalist vision. The cluster does not generally operate as a unified camp, as there are divisions among the members, and alliances are often forged on an ad hoc basis, depending on context and specific interests of the parties. Therefore, this camp has not yet succeeded in creating a cohesive, unified front against Iran and its allies.

* The Sunni Islamists: This group includes supporters of Muslim Brotherhood-style political Islam: Turkey, Qatar, Hamas, and remnants of the Brotherhood and its derivative movements throughout the region, such as Ennahdha, the dominant political party in Tunisia. The camp is not always unified, and its influence in the region is waning. However, the basic idea at its core – that “Islam is the solution” – continues to enjoy broad support in the Middle East.

* The jihadists: This camp includes the Islamic State (ISIS) and al-Qaeda and the terrorist organizations associated with them. In recent years the camp has suffered a number of serious blows, chief among them the defeat of ISIS, and this past year the organization’s leader was killed. Thus, the camp’s influence is declining, even as the Salafi-jihadist ideas at its core continue to find support in the Muslim world.

The Struggle within the States

The second arena of the regional struggle is evident within the states, where regimes face serious challenges from their populations. At the heart of this struggle are the region’s fundamental problems, which have only intensified since the upheaval began nearly a decade ago – problems such as unemployment, corruption, inequality, and overreliance on oil or external sources of financial aid. Alongside these problems, states are grappling with identity-related conflicts reflected in the suppression of minorities, tensions between Sunnis and Shiites, and tribal conflicts. In the past year, the domestic realm of the regional struggle heated up considerably with the outbreak of large-scale protests in Sudan, Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and even Iran.

The Region’s Overarching Feature: Instability

As a result of the regional struggle, the Middle East remained inherently unstable in 2019. On one end of the spectrum were the states that continued to experience war – Yemen, Libya, and Syria. At the other end were states experiencing relative stability, albeit fragile. These included Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, the Gulf states, and Turkey. In the middle were the states in which mass protests erupted in response to ongoing fundamental problems, including Sudan, Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and Iran. The ongoing demonstrations in Iraq and Lebanon are noteworthy for their anti-sectarianism and the anti-Iranian sentiment expressed among a sizable portion of the demonstrators. The killing of Qasem Soleimani has also increased anti-American sentiments in Iraq.

An additional result of the struggle is the ongoing phenomenon of constrained sovereignty that continues to characterize some states. Notwithstanding earlier predictions of its demise, the nation-state has survived as the region’s main territorial unit and ordering framework. Still, although state borders drawn up in the Sykes-Picot agreement have survived, sovereignty in many of those states remains limited to the extent that foreign actors – including the Great Powers, militias, and terrorist organizations – are present. The problem of constrained sovereignty is most glaring in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya.

In the background of the regional struggle throughout 2019, at least until the killing of Soleimani, the United States continued to reduce its involvement in the Middle East and Russian influence grew. The radical Shiite axis maintains cooperation with Russia in many areas, and while the vast majority of the Sunni states are allies or partners of the United States, they too are strengthening their ties to Russia.

The Conflict with Israel

Israel has established itself as a leading regional actor working to limit the influence of the radical Shiite axis, and to that end maintains increasing cooperation with the pragmatic Sunni states. Although the conflict with Israel is still present in the consciousness of publics across the region, in most states it is not a central issue preoccupying the regimes. The Palestinian predicament is almost entirely absent from the regional agenda, notwithstanding American efforts to increase the involvement of Arab states therein. However, breaking the glass ceiling of cooperation with the pragmatic Sunni states remains contingent on making progress in resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Recommendations

Israel must repair its relations with Jordan, which are currently in the midst of a crisis, by renewing the bilateral dialogue at the highest levels to clarify all outstanding issues between the two states. In the current regional circumstances, Israel must prepare to cope with Iranian influence mostly on its own, ideally by crafting a policy based partly on American support and on a (limited) partnership with the pragmatic Sunni states. At the same time, Israel must strengthen its cooperation with Jordan and Egypt, especially in the economic, energy, and counter-terrorism realms. Israel must prepare for the increasing likelihood that the Arab Gulf states will invest more in advanced weaponry (both American and Russian) and even seriously examine paths to nuclearization. In addition, Israel must prepare for increased tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean and more clearly delineate the extent of Israeli support for Cyprus. As for Turkey, Israel must continue to limit both Ankara’s activities in Jerusalem and its involvement with Israel’s Arab citizens, while continuing to expose Hamas’s activities on Turkish soil.

Other Countries

Egypt- The constitutional amendments approved in April 2019 strengthened President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s grip on power. However, the demonstrations that broke out in September reflected a number of economic and social indicators that threaten the stability of his regime, namely: record poverty levels, a declining standard of living, and growing anger about corruption. From Israel’s perspective, the most important development in its relationship with Egypt in the past year was the creation of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum in January. The Forum, which is headquartered in Cairo, brings together Israel, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, Jordan, Italy, and the Palestinian Authority, and it adds new geo-political and economic dimensions to Israeli-Egyptian relations.

Jordan- The Jordanian economy continues to suffer from a lack of natural resources and other local sources of income, along with pressures related to the influx of refugees from Syria. In September 2019, frustration with the economic situation sparked a month-long teachers’ strike, and the government was forced to increase wages, contrary to the commitments it made as part of the International Monetary Fund’s recovery program of 2016. There is no serious alternative to the monarchy, and King Abdullah’s patrons in the Gulf, Europe, and the United States continue to see the monarchy’s survival as a linchpin of regional stability. In 2019, relations between Israel and Jordan deteriorated significantly, reaching a nadir with the King’s decision not to renew the 25-year-old bilateral agreement regarding the Naharayim and Tzofar enclaves.

Saudi Arabia- At the end of 2019, Riyadh’s regional power and standing appear to be waning, and its influence on fundamental trends in the Middle East has weakened. To improve its standing, Saudi Arabia appears to be seeking to end the crisis with Qatar and draw down the war in Yemen. In its domestic social and cultural realms, the Kingdom is exhibiting greater openness, but low oil prices and fears of upsetting the traditional social contract have made it difficult for the regime to carry out deeper reforms. Saudi Arabia’s military inferiority relative to Iran may lead Riyadh to seek to reduce tensions with Iran by attempting to reach agreements with its longtime nemesis, as the United Arab Emirates has done. Such agreements would have implications for a number of issues, chief among them the war in Yemen, where widening rifts emerged this year in the Riyadh-Abu Dhabi alliance.

Turkey- Despite the Justice and Development Party’s defeat in local elections, Erdogan’s grip on power does not appear to be in danger, and Turkey even experienced a modest economic recovery. As reflected in its purchase of the S-400 system from Russia (despite warnings from Washington), Ankara is willing to take risks that challenge the NATO alliance from within. Despite a more assertive regional policy this past year, which included the dispatch of drilling ships and gunboats to the Eastern Mediterranean and the October 9 military operation in northeastern Syria, Turkey has not managed to increase its regional clout as leader of the Sunni Islamist camp.

Iraq- The 2018 elections were intended to increase stability in Iraq following the defeat of ISIS (despite the organization’s ongoing presence). However, mass protests in response to charges of regime corruption and the failure of the regime to address economic problems threaten stability and increase the risk of civil war. The unrest is heightened by the possibility that particularly after the killing of Soleimani and Iran’s response, Iraq will become a theater for Iran-US confrontation. The anti-Iran sentiment prevalent in the protests, and the risk it poses to Tehran, heightens the motivation of Iran and the allied Shiite militias to try to prevent any damage to Iranian influence and achieve their goal of the withdrawal of American forces.

Yemen- The fighting in Yemen has been deadlocked for three years, and the motivation of the warring parties to continue the conflict has declined. Indeed, the UAE announced its withdrawal in June 2019; the Houthis declared a unilateral ceasefire regarding Saudi territory in September; Emirati-backed southern separatists and the Saudi-backed Central Government of Yemen reached a power-sharing agreement in November; and Saudi airstrikes decreased markedly. However, devising a solution that re-unifies Yemen and satisfies key interests of the numerous actors involved will remain a significant, perhaps insurmountable, challenge. The passing of Sultan Qaboos of Oman may also prove a setback for the Saudi-Houthi peace talks that he had mediated.

North Africa and Sudan- The countries of North Africa (the Maghreb) and Sudan occupy various points on the stability spectrum. In Libya, a new round of the civil war broke out in April. In Algeria, 82-year-old President Abdelaziz Bouteflika submitted his resignation after 20 years in power, but in the elections held in December (largely under the military’s purview), a former minister associated with the Bouteflika regime was elected. Meanwhile, mass weekly demonstrations against the authorities continue. Prospects seem more optimistic in Sudan, where after months of popular protests against the regime, the army ousted President Omar al-Bashir after a 30-year tenure. Tunisia and Morocco had a relatively stable year, with a noteworthy achievement of a third round of national elections in the birthplace of the Arab Spring.

Salafi-Jihadists- As a political entity governing territory, the Islamic State (ISIS) has all but disappeared following the organization’s military defeat and the loss of its control over territory in Syria and Iraq, and its leader was killed in an American military operation. However, ISIS continues to operate as a terrorist organization with ties to similarly inclined Salafijihadist terror organizations, terror networks, and individuals operating around the world. In Syria, there remains considerable potential for the organization to recruit manpower from among those who fought against the regime in that country’s war. Although Israel is not a top priority for ISIS, the potential exists for terrorist activity against targets around the world identified with Israel and Jews. Al-Qaeda and its allies also continue to carry out terror attacks in Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East (principally in Syria, Libya, and the Sinai Peninsula).

(For full size view, please click on the map)