Publications

INSS Insight No. 1582, March 30, 2022

In August 2021 the International Monetary Fund allocated Special Drawing Rights (SDR) worth about $650 billion to member countries with the aim of increasing their foreign exchange reserves during the COVID-19 crisis. This allocation, the largest in IMF history, increased the reserves of Middle East countries by about $48 billion. The average allocation per country was equal to 1 percent of its GDP, but the allocation to Lebanon, whose economy and reserves have shrunk in recent years, amounted to about 5 percent of GDP. Iraq, Lebanon, and Jordan sold almost all their SDR in return for foreign currency worth about 2.1, 1.1, and 0.5 million dollars, respectively. On the other hand, a few politically isolated countries such as Iran, Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Venezuela have not yet cashed-in their SDR in spite of their need for foreign currency. It is doubtful whether Russia will be able to cash in its significant SDR reserves given its political isolation. These finding are not consistent with the criticism of senior United States senators that the allocation of SDR by the IMF has benefited US adversaries such as Russia, Iran, and the Taliban, or provided “special dollars for dictators.”

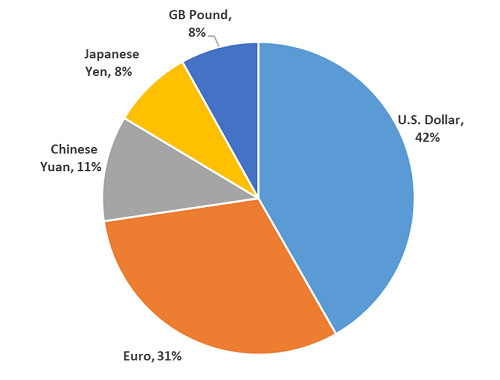

Special Drawing Rights (SDR) are an international reserve asset that supplements national reserves of foreign currency and are managed according to the rules of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Countries can keep SDR surpluses without interest (unlike hard foreign currency surpluses) as part of their foreign currency reserve or exchange them for foreign currency such as dollars. The value of the SDR is determined by a basket of international currencies (dollar, euro, Chinese yuan, Japanese yen, and pounds sterling; Figure 1). As of March 2022, 1 SDR was worth about $1.37.

SDR are allocated by the IMF to member countries, where only IMF member countries, central banks of currency unions, and International Financial Institutions can purchase and hold SDR balances. Countries can sell their SDR, but they are required to pay interest on what they have sold over the years. Interest currently stands at only 0.22 percent per annum, and could rise together with the short term interest rate in the US, Europe, and elsewhere. The value of the SDR in foreign currency and the interest rate on realized SDR holdings are published regularly by the IMF.

Figure 1: SDR currency basket, from 2015 | Note: The composition of the basket of currencies will be renewed in 2022 | Source: IMF

Allocation of SDR during the COVID-19 Crisis

In August 2021 the IMF allocated SDR to members as part of a general allocation amounting to 456 billion SDR (about $650 billion). The allocation was intended to enhance global liquidity, and in particular to help poor countries pay for medical and other expenses associated with the pandemic. This was the largest allocation in IMF history and more than tripled total global SDR reserves to about 660 billion SDR. General allocation of SDR to member countries is based on the quota of each country’s control of the IMF, which is determined according to a number of variables such as GDP, international trade, and population.

The SDR reserves of Middle East countries (including Israel and Turkey) more than tripled with this issue, from 14.7 billion ($20.4 billion) to about 49.4 billion (about $69 billion). A number of developing countries, such as Jordan, Lebanon, and Yemen, previously sold their old SDR allocation, and the new allocation increased the SDR and thus also the foreign exchange reserves of these countries (Table 1). On the other hand, the Palestinian Authority, which is not a member of the IMF, did not receive an SDR allocation.

Technically, the SDR allocation – which had American support – also increased the foreign exchange reserves of countries that are adversaries of the West, such as Russia Iran, Afghanistan, Syria, and Yemen. Therefore, the allocation met with harsh criticism from four senior Republican senators who sent an open letter to Secretary Yellen, arguing that the allocation should be abandoned, as it “would end up benefiting repressive regimes and state-sponsors of terrorism,” including China, Russia, Iran, Venezuela, and Syria. Similarly, senior officials in the Trump administration argued that the allocation “undermined international efforts to use economic pressure in order to change the bad behavior of these regimes.”[i] After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, Treasury officials announced they will work to prevent Russia from cashing in its IMF assets, which following the 2021 allocation grew to approximately $25 billion.

Sale of SDR for Foreign Currency

The use of SDR requires the sale of SDR for foreign currency to IMF member countries or to institutions eligible to hold SDR. It is doubtful whether the purchase of SDR is profitable in financial terms due to the combination of low interest rates (0.22 percent per annum) compared to two-year dollar bonds of the US Treasury (annual yield of 0.5 percent), and the low tradability of SDR compared to bonds traded on the open market. SDR does provide diversity of currencies, but it is possible to imitate this combination by purchasing a basket of bonds with a similar currency combination and level of risk but with higher yield and tradability.

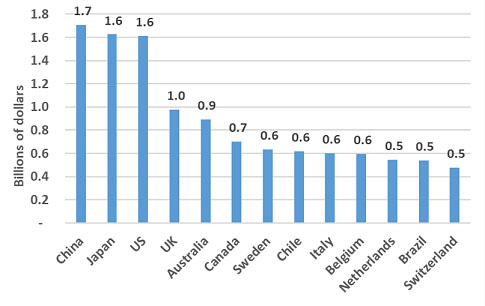

Some 30 countries, most of them developing countries, purchased SDR for about 10.2 billion SDR/$14.3 billion between the SDR allocation in August 2021 and February 2022. The biggest purchasers were China, Japan, and the United States (amounting to about 1.2 billion SDR/$1.65 billion, each). Anglo-Saxon countries such as Britain, Canada, and Australia also purchased considerable amounts of SDR (500-700 million SDR/$0.7-1 billion) and a number of countries, most of them leaders of groups of countries on the IMF Board of Directors, acquired SDR worth about half a billion dollars (Figure 2). In the Middle East, only Israel, Oman, and Algeria purchased SDR, and of limited value (about $70-95 million, each). The large majority of the SDR-buying countries are partners or at least take into account US foreign policy and sanctions, and therefore internationally isolated countries may have difficulty selling their SDR holdings for hard foreign currency.

Figure 2: Main purchasers of SDR, August 2021-January 2022 | Note: The SDR rate to the dollar (1 |USD=0.723 SDR) is correct as of March 18, 2022 | Source: Based on IMF data

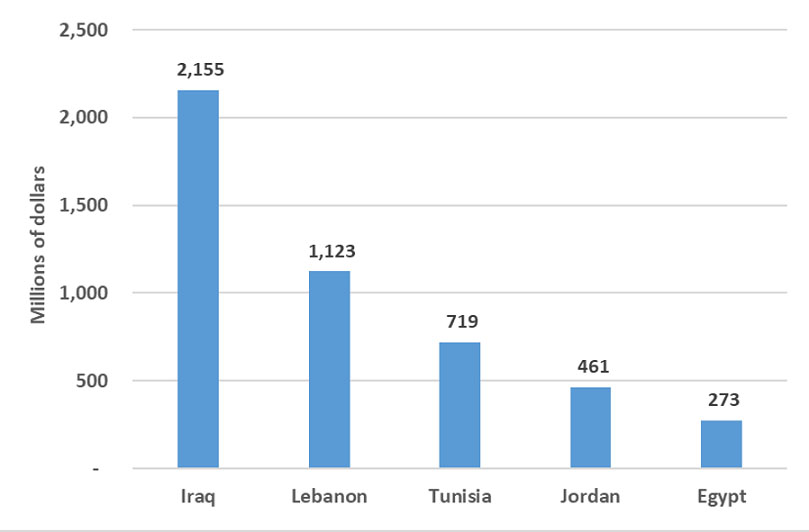

It appears that the difference between politically integrated countries and isolated countries can indeed be seen in SDR sales transactions. Five Middle East countries sold SDR during August-December 2021: Iraq (for $2.2 billion or 1.3 percent of GDP for 2020), Lebanon ($1.1 billion or 5.9 percent of GDP), Tunisia ($720 million or 1.8 percent of GDP), Jordan ($460 million or 1 percent of GDP) and Egypt ($400 million or 0.19 percent of GDP). Apart from Egypt, these countries used all the SDR holdings available to them and will not be able to realize additional holdings in the foreseeable future. Realization of SDR indicates the distress of countries that have problems borrowing foreign currency on good terms. On the other hand, Egypt retained SDR worth $2.5 billion and will be able to sell them in future. Table 1 presents the figures for all MENA countries that sold SDR.

Figure 3: Sales of SDR by Middle East Countries, August-January 2021, in millions of dollars | Note: The SDR rate to the dollar (1 |USD=0.713 SDR) is correct as of February 11, 2022 | Source: Based on IMF data

Unlike the five countries that sold SDR for foreign currency, politically isolated countries – such as Iran, Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Venezuela – did not sell a significant amount of SDR holdings in spite of their foreign currency distress. It appears that their shaky international status and US sanctions deter third countries from purchasing SDR from them. However, the allocation in August increased the SDR holdings of Iran by about $4.8 billion, of Syria by about $390 million, and of Yemen by about $470 million. Turkey, which is in foreign reserve distress – but whose foreign relations with Western countries are complex – has not yet sold SDR it accumulated after the summer allocation with a value of about $7.5 billion.

Likewise Russia is expected to find it difficult to sell its SDRs, which increased with the August 2021 allocation from $7.8 billion to approximately $24.9 billion: most of the countries that acquired SDRs in the past year are countries that imposed sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Similarly, it is unclear whether China, which purchased the most SDR in the past year, will buy any significant amount of SDR, both because of the United States reaction and because the total Chinese acquisition of SDR in the past year was less than one tenth of Russia’s SDR holdings.

Therefore, the findings of this analysis do not support the claim that the SDR allocation benefited repressive regimes and state-sponsors of terrorism in the Middle East.

Click here to view the data board

_____________

[i] D. J. Nordquist and Dan Kartz, “Where Did that IMF Covid Money Go?” Wall Street Journal, November 29, 2021. See also “Special Dollars for Dictators,” Wall Street Journal, March 21, 2021 and “IMF Funding for the Taliban?” Wall Street Journal, August 25, 2021.

Note: The author thanks the editors of INSS Insight, Tomer Fadlon, and Esteban Klor for their helpful comments.