Publications

A Special Publication in cooperation between INSS and the Institute for the Study of Intelligence Methodology at the Israel Intelligence Heritage Commemoration Center (IICC), September 5, 2024

Since the outbreak of the war in Gaza, Russian agents have been carrying out hostile influence activities against the Israeli public, aimed to undermine public confidence in the actions of the Israeli army and harm the strategic alliance between Israel and the United States. These activities are part of a long-term information warfare that Russia is waging around the world, with the intent of strengthening its standing in the international arena at the expense of the United States and its allies. Russian agents have conducted interference operations in the mainstream media and social networks, but it has not generated substantial change in the Israeli public discourse, although it has sometimes successfully penetrated the mainstream media discourse in Israel. This article examines the impact of the Russian influence operations, with the help of conventional models. It reflects an escalation in Russian hostility toward Israel, and its expansion could undermine the stability of Israeli society in wartime. Accordingly, it is recommended that Israel advance new conceptual and organizational measures to address the threat of foreign influence, in addition to increasing the Israeli public’s awareness of the phenomenon.

Introduction

Since the outbreak of the war in Gaza, there has been a rise in the involvement of Russian agents—or those who align with the Russian government’s messaging—in influencing the public discourse over social networks in Israel. While this activity promotes diverse messages related to the war and takes place on various platforms, it has one main underlying principle: the Russian information war against Israel is part of the broader cognitive campaign that Russia is waging against the West, with the goal of weakening the solidarity between Western countries and strengthening Russia’s political and military importance in shaping the world order.

In this article, we first present the principles of the Russian information war as expressed over the past decade while examining its manifestations in Israel. We then discuss at length three efforts to promote pro-Russian messages during the war in Israel—the Doppelganger campaign, sponsored articles in the Israeli media, and the Telegram group “Ukronazim”—and their degree of impact on the public discourse in Israel during the war. To this end, we have focused on publications that appeared in Hebrew in mainstream news outlets in Israel, social networks, and online forums since the outbreak of the war. We then analyze the consequences of the Russian activity while examining other possible action scenarios. We believe that the Russian activity described here is part of an escalation in Russia’s hostile activity against Israel. Finally, we present policy recommendations for addressing this trend.

Background: Russian Information War Since the Annexation of Crimea

In the years after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and increasingly since Russia’s intervention in the 2016 US presidential elections, research on Russian efforts to carry out information and influence operations has attracted considerable attention in the West. While Western researchers use a variety of terms to describe Russian influence activities, such as hybrid war, the Gerasimov doctrine, and others, the most common term in Russia to describe these activities is “information war.” It is described as “a type of confrontation between parties, represented by the use of special (political, economic, diplomatic, military and other) methods [based on different] ways and means that influence the informational environment of the opposing party [while] protecting their own [environment], in order to achieve clearly defined goals.”[1]

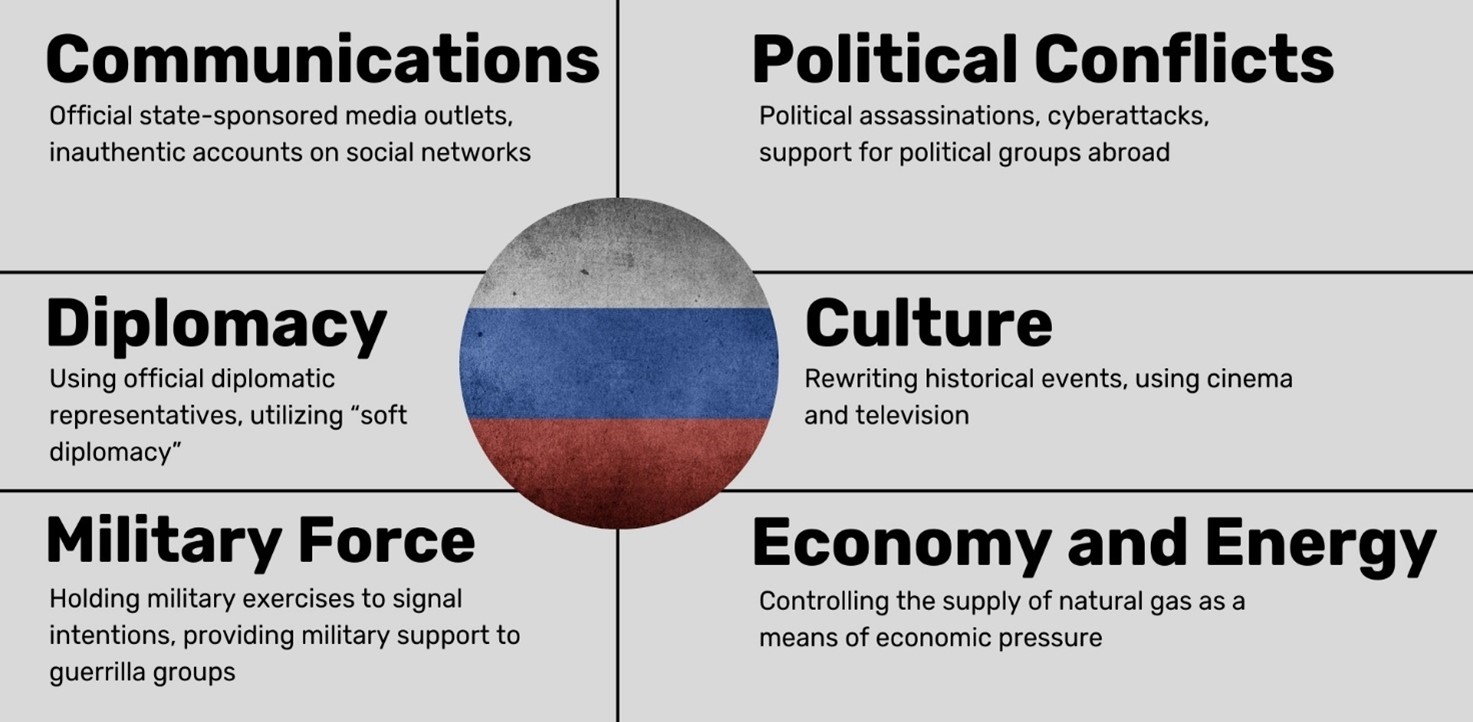

Russia’s use of information warfare against the West is constant, based on a perspective that acknowledges the existence of a state of war between the sides, even without direct military confrontation.[2] This war is being waged to achieve Russia’s strategic objectives of weakening and polarizing the West as well as bolstering the country’s international standing as a great power that dictates the rules of the game in the international arena.[3] In order to accomplish this strategic goal, and due to an understanding of Russian military inferiority vis-à-vis Western countries,[4] Russia aims to weaken the democratic and economic institutions of the West in the internal arena and to undermine the West’s legitimacy internationally.[5] Figure 1 provides details on the various measures that Russia uses to conduct its information warfare.

Figure 1. Mapping the Measures Russia Uses to Conduct Its Information Warfare. | Note: Seely, A Definition of Contemporary Russian Conflict: How Does the Kremlin Wage War?, 7.

First, since Russian influence activities are, by definition, multidimensional, the targets are not always able to recognize the concept of information war, understand that they are being targeted by Russian influence activities and assess the level of risk posed by these activities. For example, in the past it was believed that the Russian government would refrain from engaging in malicious influence activities against Germany, due to Russia’s significant economic interests in Germany.[6] However, even before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, researchers described how Russia worked to harm the official German establishment and weaken the country’s democratic institutions by enlisting local political groups sympathetic to Russia, such as the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, and wings within the Social Democratic Party (SPD).[7]

A second characteristic of Russia’s information war is the simultaneous use of several channels to transmit messages. As a rule, Russian influence activities are diverse and seemingly not controlled by a single centralized body. This creates a sense of chaos in the Russian modus operandi, but in reality, it allows for the creation of a variety of content that can reach diverse audiences on multiple platforms. According to American researchers from the US State Department, there is no single communication platform through which Russian propaganda and disinformation are disseminated. Instead, it is done through a variety of platforms that sometimes share similar content and sometimes adapt the content for different target audiences.[8] In Israel, identical content was identified as being disseminated across multiple platforms, as described below.

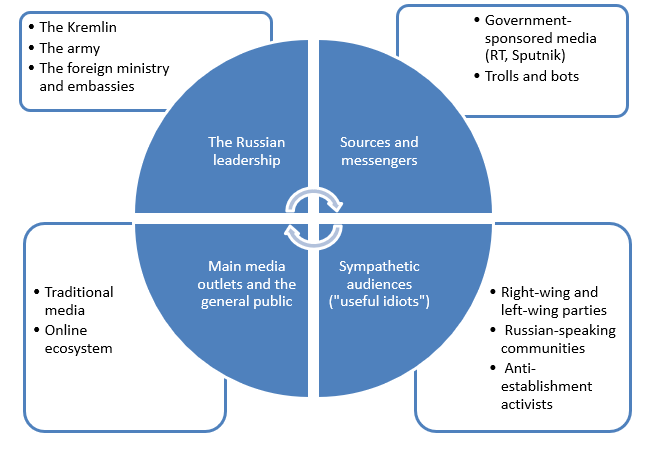

A third characteristic is the use of the target audiences themselves to disseminate messages. Researchers from RAND found in 2018 that Russian activity aims to penetrate the American news cycle. When this objective is achieved, American networks organically disseminate the information for the Russians.[9] Figure 2 presents the methods of disseminating Russian propaganda to various audiences around the world, based on Russia’s interference in the 2016 US presidential elections and Russian influence operations in other parts of the world.

Figure 2. Methods of Disseminating Pro-Russian Messages in International Influence Operations | Note: Bodine-Baron et al., Countering Russian Social Media Influence, 7.

In recent years, the app Telegram has gained a central place in the media landscape. One main reason for this is its lenient policy on the dissemination of illegal content and the use of fake accounts, which sets it apart from other social networks. As a result, several authorities in Europe have imposed fines on Telegram.[10] Moreover, the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) grants the European Union powers to compel social networks with at least 45 million European users to take action against the spread of false information. According to Telegram, as of February 2024, it has only 41 million regular monthly users in Europe, which currently exempts it from complying with the provisions of the DSA.[11] However, official sources in Europe cast doubt on this number, and in May 2024, they began a probe of the company to conduct an up-to-date assessment of the number of users.[12]

Russian Influence Activity Among the Israeli Public in the War in Gaza

Since the outbreak of the war in Gaza, individuals associated with the Russian government or expressing support for its policies have carried out a series of influence operations targeting Israeli audiences on various platforms, promoting views of the war that align with the Russian government. One example of such a view is the assertion that US policy during the war actually harms Israel’s security. It is important to note that this type of activity was already identified prior to the war, and even if the messages may have changed, the underlying objective remains the same.

For several years now, Russia has considered Israel an integral part of the Western alliance that it opposes. Previous studies have shown that Israel became a target of Russian information campaigns as early as 2019, following the arrest of Na’ama Issachar in Moscow and the subsequent influence campaign that the Kremlin waged.[13]

The deterioration of Israel’s relations with Russia following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine worsened during the war in Gaza, reaching a new low. This situation has had an impact on the information domain, with Israel becoming a target for various malicious influence activities conducted by Russian agents. The most prominent example is Israel’s inclusion in the international influence campaign known as “Doppelganger,” which Russia continuously wages against countries it perceives as enemies, such as Ukraine, as well as adversary states such as France and Germany. The Hebrew version of the campaign includes articles supposedly published on the Walla!, Mako, and The Liberal websites, claiming, for example, that Israel’s political-strategic needs should prevent it from intervening in favor of Ukraine in the war.[14]

The outbreak of the war in Gaza led to a further escalation in Russia’s information warfare against Israel. In addition to the anti-Ukrainian messages, new messages were introduced to weaken the confidence of Israeli citizens in the IDF and the government during the war and to strain strategic relations with the United States. As already mentioned, this study focuses on Russian influence activities conducted in Hebrew on social networks since the outbreak of the war.

This study most likely does not cover all Russian influence activities carried out due to technical difficulties in gathering data from the social networks themselves and locating Russian influence activity in real time (difficulties that we present later in greater detail in this section). Moreover, by focusing only on activities that involved posts in Hebrew, it is possible that we overlooked additional influence activities in other languages. However, the findings of this study clearly indicate the increasing interest of the Russian government and intelligence in what happens in Israel.

- Doppelganger

Since the onset of Russia’s war against Ukraine in February 2022, entities associated with the Russian government have been conducting an ongoing influence operation in the international arena. This operation aims to achieve two primary goals: (1) undermining Western support for Ukraine by spreading false information about alleged corruption and the supposed Nazi character of the country, and (2) sowing discord in public opinion within countries supporting Ukraine by promoting the claim that their support is causing economic and social damage.

As part of the operation, dozens of websites posing as well-known news websites from around the world, with fake news about Ukraine and the war, have been created. For this reason, the organization EU DisinfoLab, which tracks the spread of false information throughout Europe, calls the operation “Doppelganger” (a German term for two unrelated people with a similar appearance), but it is also known by the name RRN (Recent Reliable News—one of the websites used in the operation). The fake articles have been promoted throughout the internet by fictitious accounts on social networks and via sponsored posts made by inauthentic Facebook pages. The main countries targeted in the Doppelganger campaign have been France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany.[15]

Different sources have attributed the campaign’s operation to groups associated with the Russian military and regime. In July 2023, the European Council imposed sanctions on the Russian IT companies Social Design Agency and Structura National Technologies, which are associated with the Russian regime, for creating the fake websites.[16] In addition, in February 2024, the Israeli cybersecurity company ClearSky published a report stating that code strings found in the fake websites were identical to strings used in cyberattacks conducted by APT28, a group of hackers identified with Russian military intelligence (GRU), which was involved, among other things, in breaking into the email servers of the Democratic Party during the 2016 US presidential elections.[17]

After the outbreak of the war in Gaza, the Doppelganger’s operators expanded their activity in Hebrew and directed the influence operation toward promoting false narratives about the war. As in previous cases, the Doppelganger campaign made use of inauthentic accounts on X and Facebook, which simultaneously published links to fake articles on sites posing as the Israeli websites Walla and The Liberal (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. A sponsored post on Facebook linking to a fake article on a website posing as Walla accusing US policy of causing Israel losses in the war | Note: On the left, the headline reads “Pressure and ‘urgent demands’ of the US place Israel on the brink of death.” On the right: “All of this war, of all the victims, it’s just for the good of the US. But the main victim that the Americans are requesting us to sacrifice—to give up on a secure future.”

The articles published in Hebrew focused mainly on the following narratives:

- claim that US involvement in the war has caused losses to Israel and endangered it, as those influencing US policy are leftists;

- antisemitic and anti-Israel incidents from around the world;[18]

- claim that there was a transfer of weapons from Ukraine to Hamas, which were used to carry out the October 7 massacre (a narrative that will be further discussed below);

- the damage to Israel’s economy caused by the war;[19]

- claims that Hamas terrorists succeeded in their operations against the IDF (see Figure 4);

- Russia can strengthen Israel’s security vis-à-vis Iran.[20]

Figure 4. Facebook ad from a Doppelganger campaign that includes the narrative of the IDF’s withdrawal | Note: The post reads: “The barbarians in flip flops forced the IDF to withdraw. Israel lost to Palestinian gangs.”

It is important to note that in at least one case, Doppelganger activity promoted content that did not originate from fake websites: at the end of March 2024, after the terrorist attack at Crocus City Hall, a concert hall in Moscow in which at least 144 people were murdered, a group of fake accounts on X made many posts intended to arouse Israeli empathy for Russia given the attack (see Figure 5). Some posts included a link to an article about the attack that was published on a website called Omnam.life, which has since been taken down. The identity of the website’s operators is unknown, but it posted news from Israel and abroad from a pro-Russian and anti-Western perspective. The specific article that was promoted by the accounts tried to arouse the sympathy of the Israeli public for Russia following the attack by presenting it as being similar to the October 7 massacre. In both cases, the article claims that prior intelligence information received by certain bodies was not transferred to the right places, thus resulting in the attack not being prevented.[21] It is important to note that the website posted additional articles about the war, but it is not clear whether they were promoted throughout the internet.[22]

Figure 5. Fake accounts on X promoting publications intended to create empathy among the Israeli public for Russia following the terror attack in Moscow | Note: The photograph on the left reads: “Stop war, stop violence! It causes pain to see all these miserable [sic] children.” On the right: “We will stand by your side, Russia, in this difficult time. That we wish you peace.”

This activity is part of a broader pro-Russian influence operation that was carried out in the days after the terrorist attack. Thousands of fake accounts on X posted anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western claims about the incident. For example, they claimed that the United States did not prevent the attack even though it received prior information about it. Some accounts indirectly linked the attack to the war in Gaza. One account, for example, claimed that Ukraine and the United Kingdom collaborated to carry out the attack in an attempt to distract public opinion from “the loss of the Suez Canal” due to the Houthis’ attacks.[23]

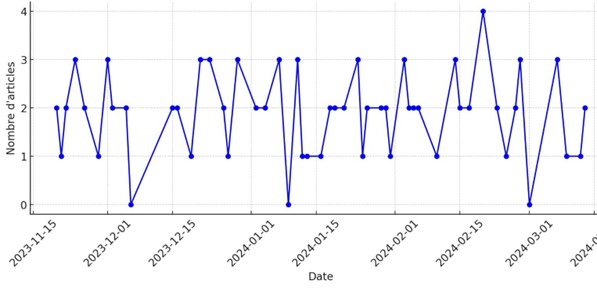

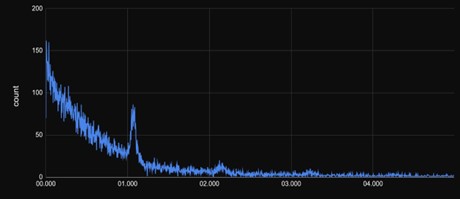

An analysis of the scope of the activity of the Doppelganger campaign shows that in the months from November 2023 to March 2024, those behind the campaign maintained a steady pace of activity (see Figure 6). During this entire period, about 80 articles were posted. Certain periods were documented when there was an increased dissemination of articles. For example, on the night between November 20 and 21, 2023, over 2,000 fake X accounts made 3,000 posts with links to fake news articles in Hebrew (see Figure 7).

Figure 6. Number of articles in Hebrew disseminated as part of the Doppelganger campaign between November 15, 2023 to March 15, 2024.

Figure 7. Number of Doppelganger campaign posts on X on the night between November 20–21, 2023.

The level of activity presented in the two graphs is consistent with the findings that attribute the Doppelganger campaign as a whole to tech companies associated with the Russian regime. This is due to the fact that the ability to consistently disseminate content in a foreign language, while adapting to the various developments in the war and conducting targeted promotions for short periods of time requires the use of considerable advanced technological and financial resources.

- Sponsored articles in the Israeli media favoring Russia

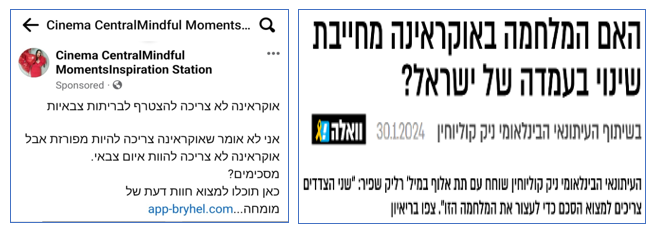

In February and April 2024, the Seventh Eye, an Israeli website, published two investigations claiming that the news sites Walla, Jerusalem Post, and Channel 13 News had published articles with pro-Russian views on the Russia–Ukraine war and the war in Gaza. According to the Seventh Eye website, these articles were published no earlier than November 2023 and included interviews with researchers, military personnel, and politicians in Israel, which were conducted by an Israeli journalist named Nick Kolyohin who works for various international media outlets, including the Chinese news agency Xinhua. According to the Seventh Eye’s investigations, these articles omitted certain statements by the interviewees that criticized Russia’s policy.

The website also discovered that none of the media outlets mentioned that the articles were published with funding from an organization called the Russia–EU Communication Platform, which presents itself as aiming to promote cooperation and understanding between Russia and EU countries. However, the organization’s description is quite vague, making it difficult to fully understand its essence and goals. In late March 2024, Channel 13 News posted two publications of this kind under the series “war and peace.” The series aimed to describe the shared interests of Russia and Western countries and the importance of promoting understanding between them. The publications were removed after the Seventh Eye’s query to Channel 13. According to Kolyohin, the articles published were important for understanding international geopolitics and his work aims to promote understanding and dialogue between Russia and the West. Kolyohin vehemently denies the claim that he is a Russian influence agent.[24]

At least one article funded by the Russia–EU Communication Platform was promoted using Doppelganger accounts, as shown in Figure 8. The use of these accounts could indicate, at least circumstantially, the existence of cooperation between the Russia-EU Communication Platform and the companies responsible for conducting the Doppelganger campaign.

Figure 8. A sponsored post on Facebook (left) leading to the article published on the authentic Walla website (right) in cooperation with journalist Nick Kolyohin.

Note: The post on the left reads: “Ukraine doesn’t need to join military alliances. I am not saying that Ukraine needs to be demilitarized but Ukraine doesn’t need to be a military threat. Agree? Here you can find an expert opinion…” The article headline on the right reads: “Does the war in Ukraine obligate a change in Israel’s position?”

- “Ukronazim”

“Ukronazim: INN” (acronym for Israel Neged Nazism [Israel against Nazism]) is a Telegram group operating in Hebrew since March 2, 2022.[25] According to its description, the group aims to present its followers with information that it believes “the Western-Israeli media and Facebook are hiding.” The group covers the Russia–Ukraine war and other events in Israel and elsewhere from a pro-Russian or pro-Israeli perspective, while also taking an anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western perspective. A central theme of their reports is portraying the Ukrainian leadership, soldiers, and citizens as having nazi characteristics.[26] The Russian mainstream media has long described Ukraine as a nazi state, but this pattern expanded significantly with the beginning of the war in February 2022.[27] In the context of events in Israel or those influencing Israel, Ukronazim represents a right-wing, and sometimes even far-right, viewpoint.[28]

information that it believes “the Western-Israeli media and Facebook are hiding.” The group covers the Russia–Ukraine war and other events in Israel and elsewhere from a pro-Russian or pro-Israeli perspective, while also taking an anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western perspective. A central theme of their reports is portraying the Ukrainian leadership, soldiers, and citizens as having nazi characteristics.[26] The Russian mainstream media has long described Ukraine as a nazi state, but this pattern expanded significantly with the beginning of the war in February 2022.[27] In the context of events in Israel or those influencing Israel, Ukronazim represents a right-wing, and sometimes even far-right, viewpoint.[28]

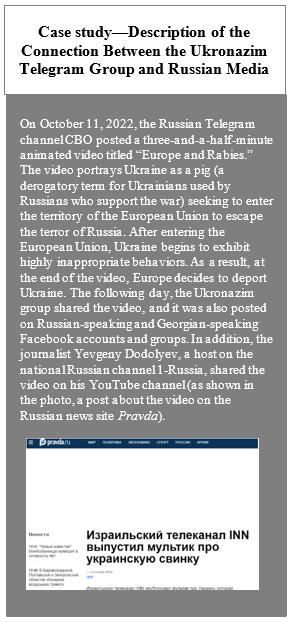

It is important to note that there are other Hebrew-language groups disseminating anti-Ukrainian content on Telegram. One example is a group called “Ukraine’s crimes,” with 240 followers. Its goal is “to provide the Hebrew-speaking population with the truth that is hidden by our media.”[29] The number of followers of these other groups is significantly less compared to Ukronazim (Ukronazim has over 1,800 followers at the time of this writing, while these groups have fewer than 300 followers). This makes Ukronazim the most significant pro-Russian group operating on Israel’s Telegram platform, increasing the interest in investigating its sources and modus operandi. While it is not possible to identify a specific entity behind the group, there has been at least one case where the Russian establishment media used a post from the Ukronazim group to spread false information about Israel and Ukraine (a more detailed description is provided in the case study).[30]

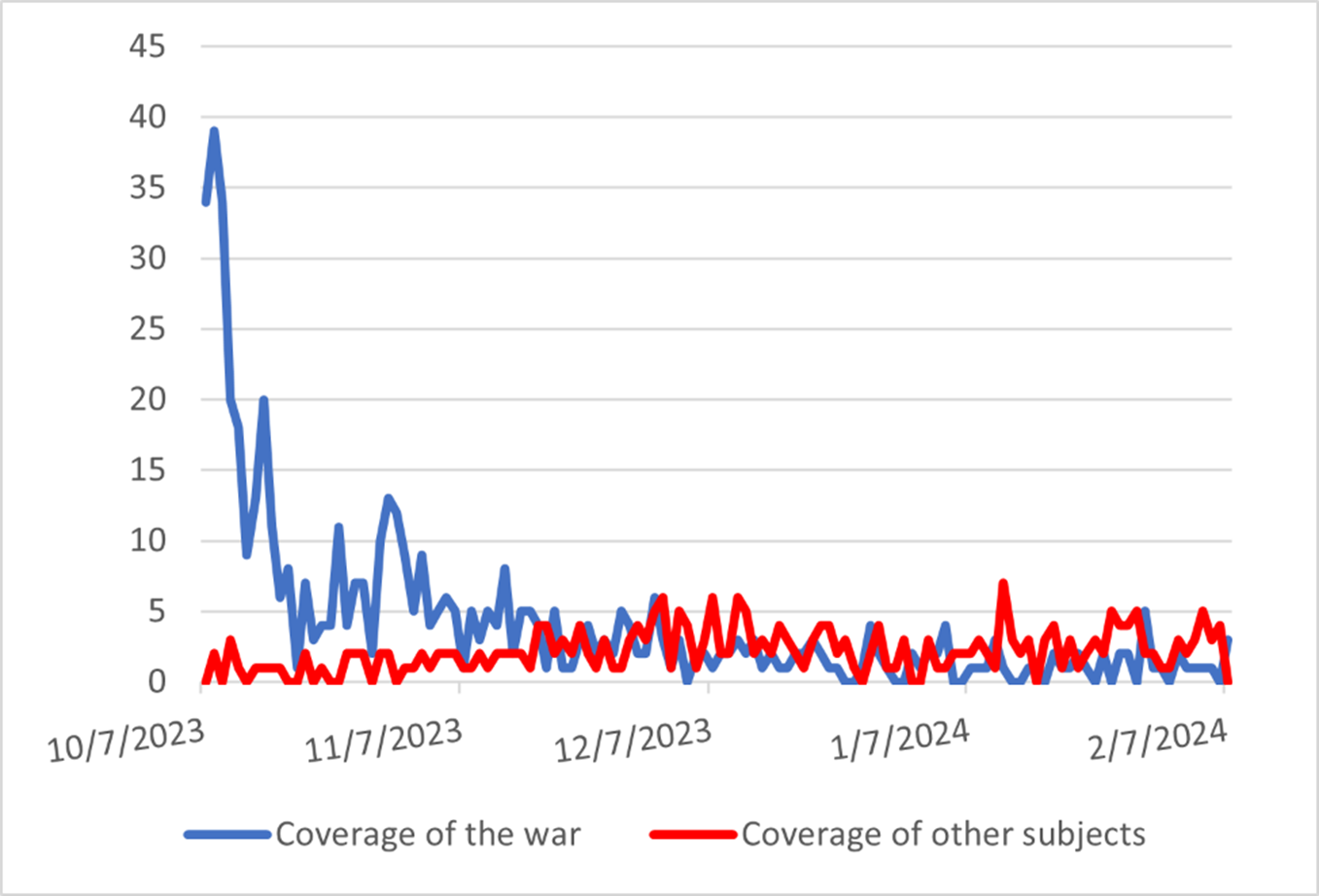

As part of this study, we analyzed the characteristics and content of the Ukronazim’s posts during the first four months of the war in Gaza (October 7, 2023 to February 7, 2024). A total of 791 posts were made in the group, of which 520 (about 66% of the total) discussed the war from various angles, mainly by describing the military actions between Israel and Hamas or presenting related events in the international arena.

As shown in Figure 9, the number of posts covering various events in the war and those discussing other issues (such as the war in Ukraine) and the ratio between the types of posts changed during those months. From the outbreak of the war until the middle of November 2023, the majority of the daily posts focused on the war. However, from that point forward, the proportion of posts related to the war decreased significantly, and most of the daily reports revolved around other issues, particularly developments in the war in Ukraine. This trend is noteworthy, especially given that prominent events in the war, such as the incident in which three hostages were mistakenly killed in Gaza by IDF fire, did not receive any response in the group. This suggests that the group’s operators prefer to cover events that can be used to frame the war as part of the international struggle between Russia and the West. The killing of the hostages was a result of an operational error, and the group’s operators were unable to connect it to their narrative.

Figure 9. The number of posts relating to the war compared to other issues in the Ukronazim Telegram group from October 7, 2023 to February 7, 2024.

An examination of the posts related to the war reveals that the issue that received the most extensive attention was the international implications of the war. These included decisions made at the UN, demonstrations for and against Israel, and the responses of official figures from various countries. There were 209 posts criticizing the policies of Western governments toward Israel, claiming that they are harmful to Israel.[31] In contrast, there were also posts highlighting the close relationship between Russia and Israel. This relationship was not just based on strategic cooperation against a shared enemy in Gaza and Ukraine but also on a connection between the nations. For example, one post showed the toys and flowers that Russian citizens had brought to Israel’s embassy in Moscow after the October 7 massacre.[32] However, this report ignores the international support that Western governments expressed for Israel, mainly manifested in the significant military aid that the United States has granted to Israel, as well as the incisive criticism that the Russian government expressed toward Israel’s actions in the war.

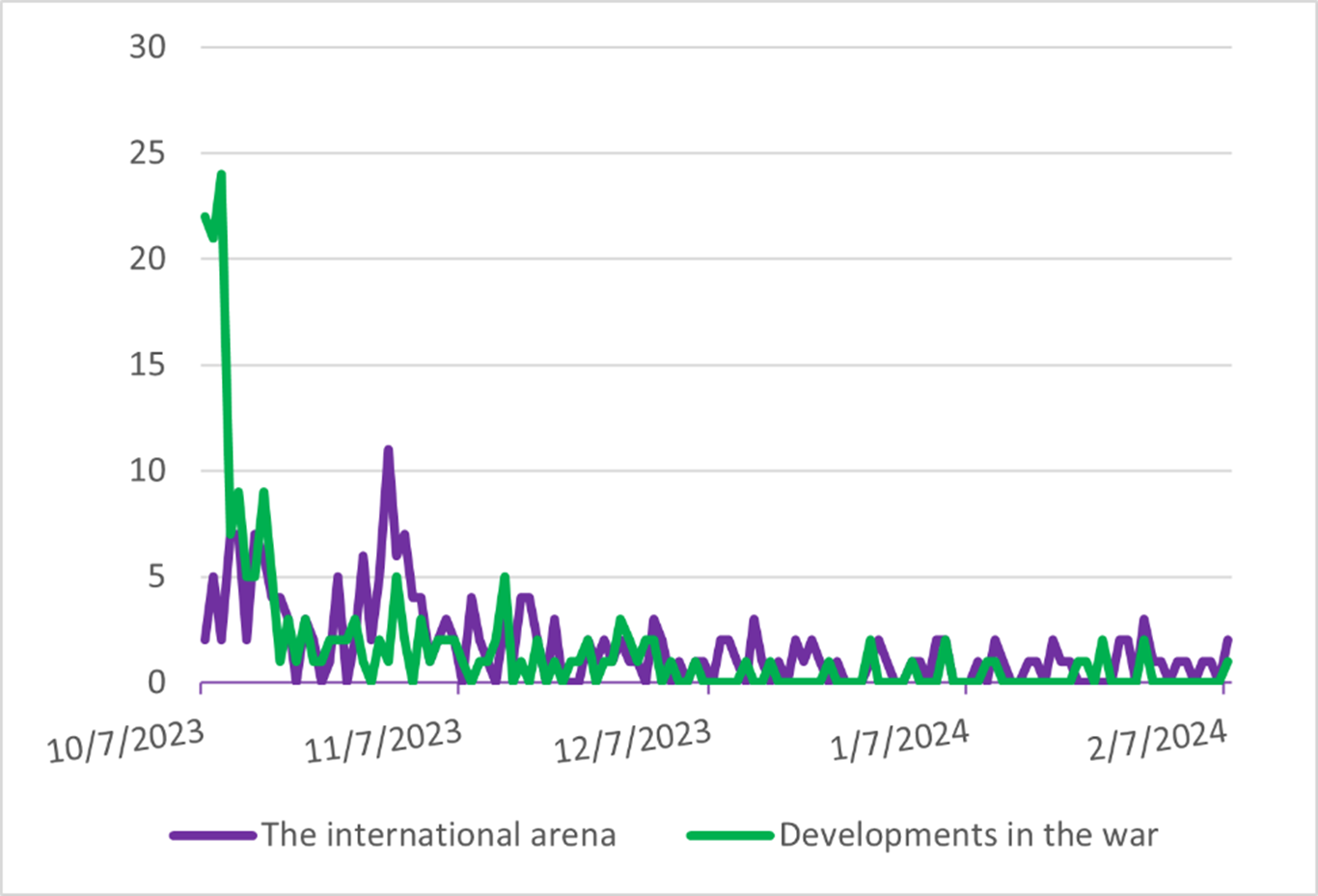

The second main issue that the group discussed was the war and its developments and their consequences for Israel and the Palestinians, including military measures, the November 2023 deal to release hostages, and political developments in Israel. A total of 196 posts were made on these issues.

On October 31, an article from the French television channel BFMTV was posted in the group. The article describes the spray-painting of Stars of David on buildings throughout Paris, apparently intended to threaten Jews.[33] This story was also promoted as part of the Doppelganger campaign, while on November 6, over 1,000 bots on X posted over 2,500 tweets about the story. France arrested four citizens on suspicion of the spray-painting and later claimed that the Fifth Service had carried out the graffiti on behalf of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), intending to cause instability in France given the rise in antisemitism there since the outbreak of the war in Gaza.[34] The Fifth Service has been described as the FSB’s unit that is responsible for carrying out political influence activities and psychological warfare outside of Russia’s borders, including for the purpose of maintaining Russia’s influence in the former Soviet states.[35]

The fact that the number of posts that discussed the international aspects of the war was greater than those that discussed developments in the war itself could indicate Russia’s tendency to seize and present events occurring in various places in the world as proof of prevailing international trends, such as the West’s policy as a source of military instability and political and economic crisis, in contrast to Russia’s responsible conduct.

Similar to the trend of posting reports connected to the war versus those not connected to it, there was also a trend reversal in the number of posts about military developments and international consequences, as shown in Figure 10. In the initial weeks of the war, the group mainly discussed direct developments in the war. However, starting from the end of October, the discussion of international aspects became comparable in scope to the description of developments in the war, and on certain days, the number of posts was even greater.

Figure 10. The number of posts presenting direct developments in the war, compared to the number of posts discussing its international aspects, from October 7, 2023, to February 7, 2024.

Other topics presented in the Ukronazim group included the transfer of weapons from Ukraine to Hamas (a false narrative that will be further discussed later),[36] describing the left in Israel as undermining the state’s security, including blaming it for the outbreak of the war, and increasing the American military aid to Israel at the expense of Ukraine.[37]

Assessing the Impact of Russian Activity in Israel

The attempt to assess the full impact of Russian activity in Israel during the war in Gaza faces three main difficulties. First, there is no uniformity in the research literature regarding the best way to measure the impact of various content posted on the internet on users who are exposed to it. One approach focuses on measuring the active interactions of users with the content, such as responses and shares (referred to as “engagement”).[38] Another approach considers the passive exposure to content (views) as the best metric for measuring impact.[39]

Second, the ability to gather and store findings about influence activity varies between social media networks. The Doppelganger activity on Facebook and X is not stored over time but is taken down by the initiators of the campaign after a predetermined period of time or removed by the social media networks themselves if they determine that the accounts involved violated their policy on inauthentic activity. In this situation, the only way to gather information from the two networks and assess their impact is by using screenshots taken during exposure to the activity, which cannot always be done. In contrast, activity on Telegram is stored over time and can be accessed and analyzed at any time. This discrepancy can lead to insufficient analysis of activity on Facebook and X compared to Telegram, thus resulting in a partial picture of the state of influence activity.

Given these difficulties, we chose to measure Russian influence activity using two principles. First, we focused on researching public responses to the claim that Ukraine transferred weapons to Hamas, which were then used in the October 7 massacre.

On October 29, 2023, journalist and news presenter Ayala Hasson broadcasted a report on the Israeli Kan television channel supposedly showing the transfer of weapons from Ukraine to Hamas.[40] From our perspective, the penetration of this anti-Ukrainian claim from social networks to the mainstream media in Israel is a successful example of Russian influence activity. Therefore, we wanted to investigate the path of its penetration into the Israeli public discourse and its impact on it. This claim was previously published as part of the Doppelganger campaign and in the Ukronazim group.

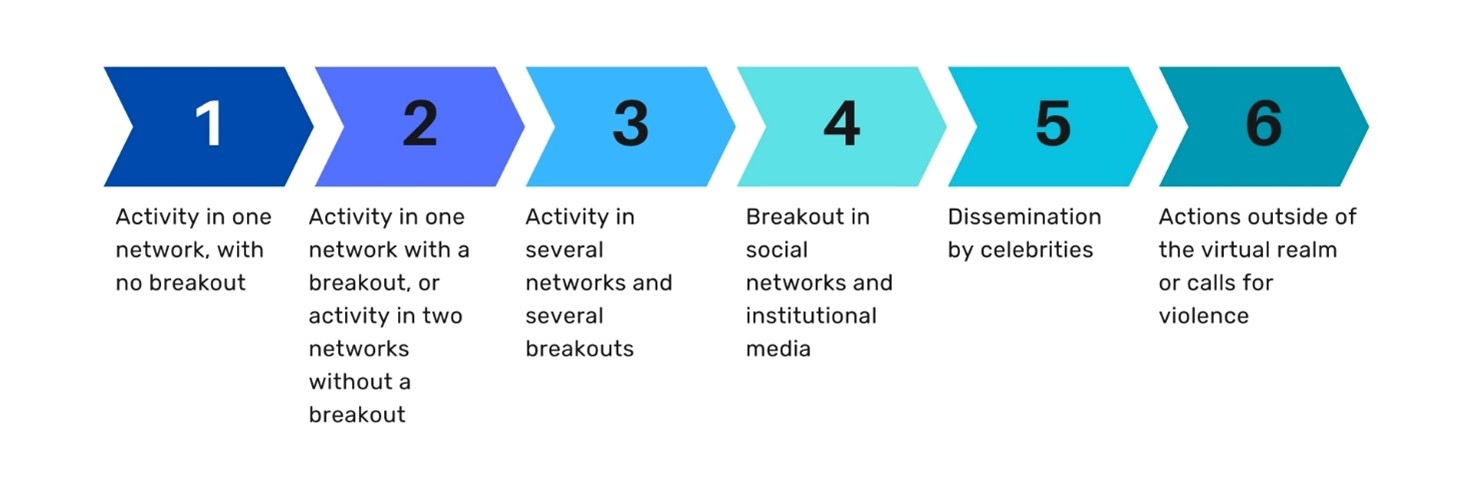

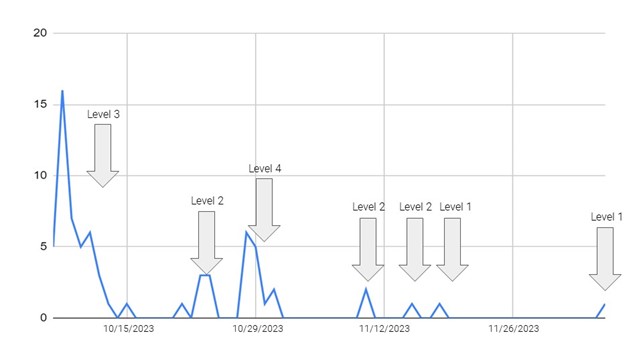

Third, wherever possible, we measured the number and nature of active and passive interactions of users with social media content that included the narrative of Ukraine transferring weapons to Hamas. We performed a textual analysis of the written responses to posts those users shared, and we also analyzed the type of emojis that users posted in response to posts, using a guide that explained the meaning of over 200 emojis.[41] We used this analysis to categorize responses as supporting the narrative, opposing it, or not expressing an opinion on it. However, we used the “breakout scale” approach as the main method of tracking how the narrative spread on the internet and measuring its influence. The approach was developed by Ben Nimmo, the head of the threat intelligence team at Meta and an expert on influence and disinformation campaigns.[42] According to this approach, each influence operation can be rated on a six-step ladder, with each stage representing a different level of proliferation of influence operations. At the bottom and most basic level are influence operations that are carried out on a single social platform and whose messages do not spread to other places. At the top level are influence operations that lead to tangible impact on the world outside the virtual realm.[43]

Figure 11. The breakout-scale model, which ranks the intensity of influence operations according to the pattern of their dissemination.

In tracking the discourse surrounding the claim that Ukraine transferred weapons to Hamas, we focused on posts that not only supported the claim but also opposed it, cast doubt on it, or presented alternative versions of this narrative. We recognize that Russia’s information campaigns aim not only to convince the target audience of the truth of a certain claim but sometimes intend to create public confusion and uncertainty regarding a certain issue, with the objective of weakening the public’s opposition to Russia’s actions. The existence of several versions of this claim—even if they are contradictory or posted by people unconnected to it—could serve this goal.[44]

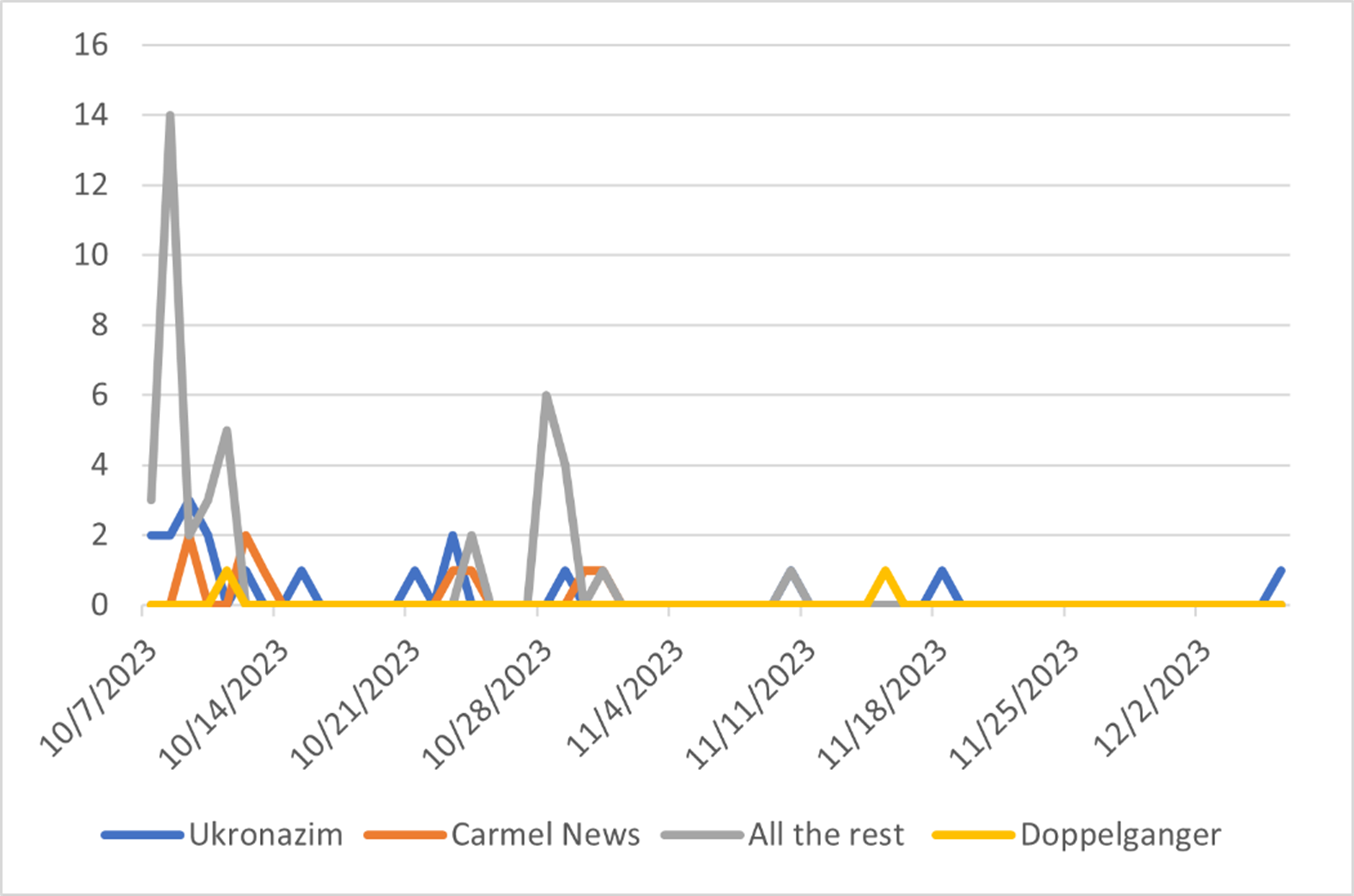

As part of our research, we found that the claim that Ukraine had transferred weapons to Hamas had been widely shared throughout the internet in Israel. This claim was shared in three different arenas: (1) pro-Russian arenas (such as the Ukronazim group on Telegram and false articles circulated as part of the Doppelganger campaign), (2) the arena targeting people from former Soviet states in Hebrew (such as the Telegram group “Carmel News—news from the former Soviet Union and Israel”—with approximately 34,500 followers as of May 26, 2024), and (3) “open” arenas that do not have a specific target audience (such as X, Facebook, the television channel Kan, and online forums like Rotter). Our analysis of these arenas shows that the discourse surrounding the claim of weapons transfers from Ukraine to Hamas, the presentation of the claim, and responses from users took place on the internet over a two-month period from the onset of the war until December 6, 2023.

Figure 12 maps the discourse on the internet during this period, categorized by the arena of activity. From Figure 12, we can infer that the discourse in Israel took place mainly in October, whereas the highest number of posts was observed during the first week of the war and then again from October 28 to 30. During these times, most of the posts were documented in “open” arenas. The extensive discussion during the first week of the war can be attributed to the sense of surprise felt by the Israeli public following the outbreak of the war, which led them to seek explanations for how the debacle occurred. Toward the end of October, the discourse continued after Hasson’s broadcast.

Figure 12. Documentation of the discourse in Israel about the claim of weapons transfers from Ukraine to Hamas, by place of publication, October 7 to December 6, 2023.

We used Nimmo’s breakout scale model to measure the impact of promoting the message (or competing versions of it) among the public in Israel. Figure 13 charts the application of the model to the discourse in Israel.

Figure 13. Characterization of the discussions on the narrative of weapons transfers from Ukraine to Hamas, using the breakout-scale model.

According to Figure 13, the model categorizes the promotion of the pro-Russian narrative about weapons transfers to Hamas, as well as the responses to it during the first week of the war as level 3 influence activity, representing influence operations that are publicized simultaneously across multiple platforms (but not in the mainstream media). During this period, the discourse on the narrative took place in the Telegram groups Ukronazim and Carmel News, on X, on Facebook, and in at least one case, the sharing of content was documented in the Ukronazim group on Facebook. Subsequently, the discussion on the issue decreased, resulting in a decline in the level of influence to level 2, which represents influence activities that occur separately on different platforms or within a single platform but in multiple places (for example, such as posting the same content in different Facebook groups).

Following the broadcast on the Kan channel, the level of influence rose to level 4, the highest level documented during the war. Level 4 is characterized by influence activities that involve narratives that move from social networks into mainstream media. In this case, however, a reverse move occurred—from television to social networks. It is important to note that following the Kan broadcast, Ukraine’s embassy in Israel posted a statement on its Facebook page completely denying the claim of weapons transfers to Hamas.[45] This denial indicates the extensive reach of the discourse that was documented in the Israeli media and social media networks after the broadcasting of the report on Kan.

In the subsequent weeks until December 6, the level of influence in promoting the narrative decreased to level 2 and then level 1, with level 1 representing influence operations that are only publicized on a single platform, without being disseminated to other groups, either within or outside of it.

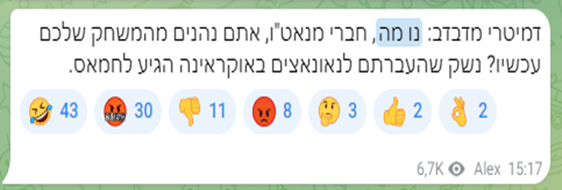

Finally, we characterized the various user responses to the report of weapons transfers to Hamas and found two types of responses in each arena. In the Ukronazim group, which also published the narrative over the longest period of time (from October 7 to December 6), most of the user responses did not express an opinion related to this claim, but those that responded to the story supported it. In contrast, in the Carmel News group, the opposite was observed. In cases where the group posted declarations from official Russian sources supporting the story, most users expressed disagreement with them, mainly by using angry or ridiculing emojis (see Figure 14). Instead, posts in the group promoted an opposing view, that official Russian bodies transferred weapons from Ukraine to Hamas.[46]

Figure 14. Post relating to the official Russian declaration of the story of the weapons transfers to Hamas in the Carmel News Telegram group, to which users responded with distrust | Note: “Dimitry Medvedev: Come on, NATO members, are you enjoying the game now? Weapons that you transferred to the neo-Nazis in Ukraine have reached Hamas.” From Carmel News (@AlexmehaCarmel), Telegram, October 9, 2023, https://t.me/alexmehacarmel/10037.

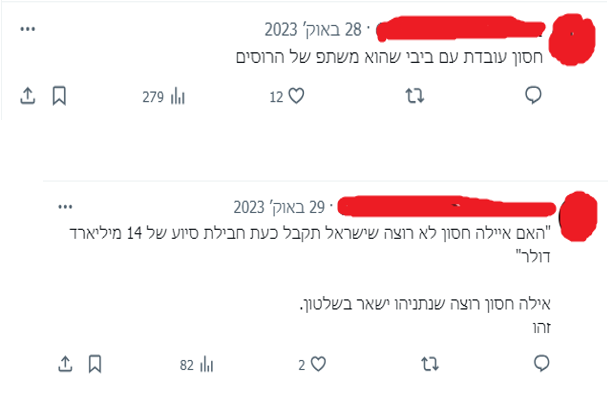

In those arenas addressing the entire Israeli public, there was more extensive discussion of the story after the publication of the report on the Kan channel. This was reflected in the increased number of responses to each post of this nature, compared to the responses documented in the first week of the war. As a rule, the responses to the anti-Ukrainian narrative in these arenas were not only characterized by distrust toward it, but also linked it to the political rift in Israel. For example, after the publication of the report on the Kan channel, many respondents on X claimed that the publication of the item served Netanyahu, as they believed that the prime minister was actually operating on behalf of the Russian government. Furthermore, in at least one case, it was suggested that the publication of this claim by an official media outlet in Israel could potentially harm Israel–US relations (see Figure 15).

Figure 15. User responses on X to the publication of the report on the transfer of weapons from Ukraine to Hamas on the Kan channel.

Note: The first response reads: “Hasson works with Bibi who is a collaborator of the Russians.” The second response: “Doesn’t Ayala Hasson want for Israel to receive now the aid package of 14 billion dollars. Ayala Hasson wants that Netanyahu will stay in power. That’s it.” From Daniel Rakov (@rakovdan), “Why does Ayala Hasson bring to prime time on a public broadcast an item that is not clear, supposedly about western weapons transferred to Gaza from Ukraine?” [in Hebrew] X, October 28, 2023, https://x.com/rakovdan/status/1718343468219576720.

The posting of responses itself is not a problem as it is part of the freedom of expression in Israel. However, Russian influence agents could have promoted these types of postings in greater numbers, thus deepening the rift in Israeli society during the war in Gaza. Inflaming this kind of discourse, if it took place, would promote the fundamental principles of Russian information warfare: creating division in societies and giving the impression that the West is responsible for the military instability in the world (as it was claimed that the weapons transferred to Hamas originated from NATO military aid to Ukraine, in an attempt to refute such claims against Russia).

Conclusion

The findings presented above describe various pro-Russian influence operations aimed at the Israeli public since the outbreak of the war in Gaza. In this context, the operations have targeted both the mainstream media and social networks, with the messaging adapted to major developments (as seen after Iran’s attack on Israel) and with different branches in the operation working in coordination (such as promoting the article published with funding from the Russia–EU Communication Platform using Doppelganger accounts). In particular, the extensive dissemination of hundreds of pro-Russian posts in the Ukronazim Telegram group—including the spread of the narrative on the weapons transfers to Hamas—is consistent with Telegram’s central role in spreading false pro-Russian information in Europe. Simultaneously, in all channels, there are messages that describe the international dimension of the war in Gaza from the Russian perspective: the involvement of Ukraine and the United States in undermining the regional military order, while Russia, in contrast, promotes stability in the region.

Russia’s information warfare during the war in Gaza also included characteristics identified in research dating back to 2014. The dissemination of the narrative of weapons transfers from Ukraine to Hamas targeted the local audience, as found by researchers at the RAND Institute regarding the United States. After pro-Russian accounts and groups spread the narrative in the first few days of the war, the Kan channel published a report on the claim. However, an assessment of the likelihood of success of the Russian activity, which seems to aim at undermining Israeli social stability during the war, reveals a more complex picture. This is evident in the analysis of publication patterns and responses to the weapons transfer narrative: Foreign agents interested in influencing the internal discourse in Israel during the war can do so by focusing on specific issues and provoking lively discussions about them. However, the ability to maintain a particular narrative over time is more difficult, as shown by the limited impact that the publication of the narrative about weapons transfers to Hamas in November and December had on the Israeli public.

The significance of creating the pro-Russian discourse is not necessarily expressed by accepting or rejecting the narrative that is publicized. (Notably, the acceptance of the narrative about the weapons transfers occurred only within the pro-Russian Telegram group, Ukronazim.) Rather, the importance lies in the ability to exacerbate the existing political divisions in Israel, as evidenced by the discourse around the weapons transfers to Hamas. However, the Russians’ intention in this specific activity was to denigrate Ukraine and not to further polarize Israeli society. Nonetheless, as additional influence activities relating to the war continue to occur, there is an increased risk of a cumulative effect that could undermine Israel’s political and social cohesion at a very sensitive time when there is a possibility of expanding the military campaign against Hezbollah, potential for direct conflict between Israel and Iran, and growing demand from the public to hold early elections due to criticism of the political leadership’s actions before and during the war.

Another scenario to consider is the growing use of artificial intelligence (AI) in Russian influence operations against Israel. This was demonstrated during the war when an account belonging to the Doppelganger network published a deepfake video showing an IDF soldier inviting soldiers from Ukraine to join the fighting for Israel in exchange for citizenship and payment.[47] This phenomenon extends to Doppelganger operations targeting the international community, such as the dissemination of fake news on fictitious news sites.[48] The success of Russian influence operations will likely increase with the expansion of the use of artificial intelligence, as AI-generated content can be disseminated quickly and widely, provoke more responses from users, and be more difficult to identify and remove.[49]

All the findings discussed here demonstrate a series of isolated actions that have been somewhat successful in integrating pro-Russian narratives into the Israeli discourse. If Russia decides to place greater importance on influencing the Israeli public and dedicating more resources to this, the influence operations could expand and be more successful in undermining Israeli society.

Policy Recommendations

Based on the findings presented here, it is recommended that Israel address Russian foreign influence in several ways:

- Conceptual and structural organization of addressing foreign influence

Since the end of the 2010s, Israel has become a target of numerous foreign influence operations, particularly by Russia and Iran. However, a comparison with other Western countries that have faced this threat reveals that Israel’s conceptual and structural infrastructure for addressing foreign influence operations is inadequate. In the theoretical realm, over the past decade, Western countries and organizations such as NATO and the EU have carried out extensive research and conceptualization on the principles and elements of cognitive and influence operations, such as the principle of strategic communications and Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI).[50] In the structural realm, several bodies in the Israeli government, especially the General Security Service (Shin Bet), are responsible for dealing with these phenomena, [51] while the Israel National Cyber Directorate has become more active in addressing these issues since the onset of the war in Gaza. Whether Israel assigns the responsibility of addressing foreign influence to an existing body or creates a new one, it is crucial that this effort be based on a well-developed methodological foundation and draw comprehensively o knowledge from various fields, including technology, psychology, law, and more.

- Raising public awareness of the threat of Russian influence

Two parallel processes should be carried out to raise public awareness of the characteristics and dangers of Russian influence. In the public sphere, campaigns should be launched that present citizens with the characteristics of the threat and provide them with tools to identify fake posts on social media. During the war, the National Cyber Directorate launched a public campaign that warned the public about sharing fake information as a whole.[52] While the public sees the campaign as important and beneficial, there is room to improve the way the public is warned about the threat by explicitly presenting the threat of foreign influence operations in general and the characteristics of Russian influence operations in particular. The effectiveness of this method of immunizing the public to future influence threats has been proven by research. A series of experiments performed by Cambridge University and the tech incubator Jigsaw, which belongs to Google, found that user exposure to short videos presenting types of false information they could encounter (for example, information based on prejudices against certain groups in society) improved their ability to identify false information.[53] Google used this method to refute false information published about Ukrainian refugees who fled to Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Poland.[54]

At the same time, it is important to raise awareness among media outlets in Israel about the fact that Russian agents could contact them and ask to conduct interviews while hiding their true identity.[55] Such cooperation, which takes place without proper disclosure regarding the individuals involved, could produce content that contributes to strengthening Russia’s information war and weakening Israel domestically and internationally.

- Forming collaborations with Western organizations in the struggle against Russian influence

Russian influence operations pose a strategic threat to the State of Israel as they could exacerbate political instability and internal discord within Israel as well as harm its international reputation during times of conflict. Given that Russia carries out similar influence operations against other Western countries, it is recommended that Israeli agencies involved in countering disinformation collaborate with similar organizations in Europe to facilitate mutual learning about influence threats, underlying intentions, and the most effective ways of addressing them. One example of a Western project in which Israel could participate is EU-HYBNET,[56] a project funded under the EU’s Horizon 2020 research program. EU-HYBNET brings together experts from the private sector and civil society who analyze emerging threats in hybrid warfare, the dissemination of false information, foreign interference, and potential responses to them. The network of experts collaborates with governmental and security bodies in Europe and beyond,[57] including NATO’s Strategic Communications Center of Excellence (StratCom COE).[58] Membership in the network is also open to countries associated with the European Union, including Israel. This cooperation would allow Israeli public sector agencies, private companies, academic institutions, and civil society organizations to align with NATO’s policy, which restricts the operation of actors supported by Russia in the information domain.

[1] Ofer Fridman, “‘Information War’ as the Russian Conceptualisation of Strategic Communications,” RUSI Journal 165, no 1 (2020): 46, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2020.1740494.

[2] Janusz Bugajski, “For Russia, War with the US Never Ended—and Likely Never Will,” The Hill, April 3, 2019, https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/437138-for-russia-war-with-the-us-never-ended-and-likely-never-will/.

[3] Brian Klass, “Stop Calling it ‘Meddling.’ It’s Actually Information Warfare,” Washington Post, July 17, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/democracy-post/wp/2018/07/17/stop-calling-it-meddling-its-actually-information-warfare/; Defense Intelligence Agency, Russia Military Power- Building a Military to Support Great Power Aspirations (Washington, 2017), 39.

[4] Bob Seely, A Definition of Contemporary Russian Conflict: How Does the Kremlin Wage War? (Henry Jackson Society, June 2018), 2, https://henryjacksonsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/A-Definition-of-Contemporary-Russian-Conflict-new-branding.pdf.

[5] Elizabeth Bodine-Baron, Todd C. Helmus, Andrew Radin, and Elina Treyger, Countering Russian Social Media Influence (Santa Monica, RAND, 2018), 2, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2740.html.

[6] Stefan Meister, “The ‘Lisa Case’: Germany as a Target of Russian Disinformation,” NATO Review, July 25, 2016, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2016/07/25/the-lisa-case-germany-as-a-target-of-russian-disinformation/index.html.

[7] Jeffrey Mankoff, “Russian Influence Operations in Germany and Their Effect,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 3, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russian-influence-operations-germany-and-their-effect.

[8] U.S. Department of State, GEC Special Report: August 2020 Pillars of Russia’s Disinformation and Propaganda Ecosystem (August 2020), https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Pillars-of-Russia%E2%80%99s-Disinformation-and-Propaganda-Ecosystem_08-04-20.pdf.

[9] Bodine-Baron et al., Countering Russian Social Media Influence, 7–11

[10] Natália Tkáčová, Disinformation on Telegram in the Czech Republic: Organizational and Financial Background (Prague Security Studies Institute, January 2024), 4, https://www.pssi.cz/download/docs/10984_disinformation-on-telegram-in-the-czech-republic-organizational-and-financial-backround.pdf.

[11] Alberto Nardelli, Daniel Hornak, and Jeff Stone, “Too Small to Police, too Big to Ignore: Telegram Is the App Dividing Europe,” Bloomberg, May 28, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-05-28/telegram-pro-russian-groups-spread-disinformation-and-eu-is-powerless.

[12] Matthew Connatser, “EU Probes Telegram, Because Size Matters for Regulators,” The Register, May 28, 2024, https://www.theregister.com/2024/05/28/eu_probes_telegram/.

[13] Vera Michlin-Shapir and Daniel Rakov, “‘Pray for Na’ama’—Russian Information War Against Israel,” Institute for National Security Studies and Israel Intelligence Heritage and Commemoration Center, 2024, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/naama /.

[14] Omer Benjakob, “Global Russian Disinformation Op Targeted Israel, U.S. Jews,” Haaretz, June 13, 2023, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/security-aviation/2023-06-13/ty-article/fake-news-sites-and-antisemitic-memes-global-russian-op-targeted-israel-u-s-jews/00000188-b4f9-d1d6-a7b9-fffd4d1a0000.

[15] Ben Nimmo and Mike Torrey, Taking Down Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior from Russia and China (Meta, September 2022), 13, https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/CIB-Report_-China-Russia_Sept-2022-1-1.pdf; “What is the Doppelganger Operation? List of Resources,” EU Disinfo Lab, https://www.disinfo.eu/doppelganger-operation/; Florian Reynaud and Damien Leloup, “‘Doppelgänger’: The Russian Disinformation Campaign Denounced by France,” LeMonde, June 13, 2023, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/pixels/article/2023/06/13/doppelganger-the-russian-disinformation-campaign-denounced-by-france_6031227_13.html.

[16] Council of the European Union, “Information Manipulation in Russia’s War of Aggression against Ukraine: EU Lists Seven Individuals and Five Entities,” press release, July 28, 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/07/28/information-manipulation-in-russia-s-war-of-aggression-against-ukraine-eu-lists-seven-individuals-and-five-entities/; Social Design Agency, “Open Sanctions,” (n.d.), https://www.opensanctions.org/entities/NK-d3FQdNM59TvJzyw2UsBJKE/; Structura National Technologies, “Open Sanctions,” (n.d.), https://www.opensanctions.org/entities/NK-CEV5sV2zekBZ4RkNusj9px/.

[17] ClearSky Cybersecurity, “Doppelgänger NG: Cyberwarfare Campaign,” February 22, 2024, https://www.clearskysec.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/DoppelgangerNG_ClearSky.pdf; Andy Greenberg, “Russia’s Fancy Bear Hackers Are Hitting US Campaign Targets Again,” Wired September 10, 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/russias-fancy-bear-hackers-are-hitting-us-campaign-targets-again/.

[18] “Members of Parliament from South Africa Found an Unknown Animal in Israel,” Doppelganger website of Walla!, November 24, 2023; “The British Are Changing Their Approach: Hamas Is Not Terrorists and Israelis Are ‘The White Occupiers,’” [in Hebrew] Doppelganger website of Walla!, March 11, 2024, https://archive.is/gbgXs#selection-2251.0-2254.0.

[19] “Economy During War: How Much Has Israel Lost,” Doppelganger website of Walla!, January 2, 2024.

[20] FakeReporter (@Fake Reporter), “The Russian influence campaign that finances Facebook ads and promotes articles on fake news sites a X did not leave its hands behind in the wake of the Iranian attack either,” [in Hebrew] Twitter (now X), April 16, 2024, https://twitter.com/FakeReporter/status/1780240241661518146.

[21] “The Attack in Moscow,” Omnam.life, March 23, 2024.

[22] “Israeli Withdrawal,” Omnam.life, April 8, 2024.

[23] Omer Benjakob, “After Moscow Attack, New Russian Influence Campaign Tries to Pin the Blame on the West in Sloppy Hebrew,” Haaretz, March 26, 2024, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/security-aviation/2024-03-26/ty-article/.premium/after-moscow-attack-new-russian-campaign-tries-to-pin-blame-on-west-in-sloppy-hebrew/0000018e-7b63-d96c-af9f-7fe353570000.

[24] Itamar Baz, “Walla? Da!” [in Hebrew] Seventh Eye, February 23, 2024, https://www.the7eye.org.il/511397; Itamar Baz, “Russia Is Depicted Like North Korea, As if a Terrible Government Is Behind Everyone,” [in Hebrew] Seventh Eye, April 3, 2024, https://www.the7eye.org.il/515504.

[25] “Ukronazim: INN,” TGStat website (continuously updated), https://tgstat.com/channel/@ukroterror2/stat.

[26] Ukronazim: INN (@ukroterror2), “The dark times in Ukraine continue. Zelensky approved changing the names of Jewish Streets of Kherson, Herzen, and Levitan to new names (one of which is a Nazi . . . and the other after a painter,” [in Hebrew] Telegram, April 2, 2024, https://t.me/ukroterror2/11339.

[27] Charlie Smart, “How the Russian Media Spread False Claims About Ukrainian Nazis,” New York Times, July 2, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/07/02/world/europe/ukraine-nazis-russia-media.html.

[28] Ukronazim: INN (@ukroterror2), “Benjamin Netanyahu’s statement about most of the dishonest media in Israel: Most channels and newspapers are intended to harm Israel and the Jewish people, as they serve the anti-Israeli narrative,” [in Hebrew] Telegram, March 13, 2023, https://t.me/ukroterror2/8118.

[29] “The Ukraine’s Crimes,” [in Hebrew] Telegram group, https://t.me/pshaimukrainim.

[30] About Yevgeny Dodolev, see DBpedia (n.d.), https://dbpedia.org/page/Yevgeny_Dodolev; Tinatin Tvauri, “Real Creators Behind the Ukrainian Pig Animation Distributed in the Name of an Israeli Channel?” Myth Detector, October 19, 2022, https://mythdetector.ge/en/real-creators-behind-the-ukrainian-pig-animation-distributed-in-the-name-of-an-israeli-channel/; Ilya Ber and Daniel Fedkevich, “Is it True that an Israeli TV Channel Showed a Cartoon about a Ukrainian Pig and Europe?” [in Russian] Provereno, October 25, 2022, https://provereno.media/blog/2022/10/25/pravda-li-chto-izrailskij-telekanal-pokazal-multfilm-pro-ukrainskuju-svinku-i-evropu/.

[31] Ukronazim: INN (@ukroterror2), “The Russian foreign minister – Russia and Israel are in a similar situation,” [in Hebrew] Telegram, December 28, 2023, https://t.me/ukroterror2/10700.

[32] Ukronazim: INN (@ukroterror2), “In Russia in Moscow they continue to bring flowers and toys to the Israeli embassy every day,” [in Hebrew] Telegram, October 13, 2023, https://t.me/ukroterror2/10064.

[33]Ukronazim: INN (@ukroterror2), “The situation in France,” [in Hebrew] Telegram, October 31, 2023, https://t.me/ukroterror2/10252.

[34] Clea Caulcutt, “France Condemns Russian Disinformation Campaign Linked to Stars of David Graffiti,” Politico, November 9, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/france-condemns-russia-involvement-stars-of-david-graffiti/; “France Blames Russia’s FSB for Anti-Semitic Star of David Graffiti Campaign,” France24, February 23, 2024, https://www.france24.com/en/france/20240223-france-blames-russia-s-fsb-for-anti-semitic-star-of-david-graffiti-across-paris.

[35] “Secret Russian Intelligence Unit May Conduct Terrorist Operations in Eastern Europe and the Baltics,” Robert Lansing Institute, February 25, 2022, https://lansinginstitute.org/2022/02/25/secret-russian-intelligence-unit-may-conduct-terrorist-operations-in-eastern-europe-and-the-baltics/.

[36] Ukronazim: INN (@ukroterror2), “The British Bellingcat writes that the corruption of the Ukrainian army ministers led to the fact that a huge amount of Western weapons reached Palestine,” [in Hebrew] Telegram, October 10, 2023, https://t.me/ukroterror2/9988.

[37] Ukronazim: INN (@ukroterror2), “The day will come and the left will sell the country to its core. They may have been involved in yesterday’s atrocity,” [in Hebrew] Telegram, October 8, 2023, https://t.me/ukroterror2/9922; Ukronazim: INN (@ukroterror2), “Zelensky: Why not for me?” [in Hebrew] Telegram, October 17, 2023, https://t.me/ukroterror2/10122.

[38] John D. Gallacher and Marc W. Heerdink, “Measuring the Effect of Russian Internet Research Agency Information Operations in Online Conversations,” Defence Strategic Communications 6, no. 5 (June 2019): 155–198, https://doi.org/10.30966/2018.RIGA.6.5.

[39] Rui Liu et al., “Using Impression Data to Improve Models of Online Social Influence,” Scientific Reports 11, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96021-3.

[40] “Ayala Hasson Faces Serious Accusations: Fake News, Lack of Professionalism,” [in Hebrew] ICE, October 30, 2023, https://www.ice.co.il/tv/news/article/985956.

[41] “200+ Emojis Explained: Types of Emojis, What do they Mean & How to Use Them,” Smartprix, March 6, 2024, https://www.smartprix.com/bytes/a-guide-to-emojis-types-of-emojis-what-do-they-mean-how-to-use-them/.

[42] About Ben Nimmo, see Lawfare (n.d.), https://www.lawfaremedia.org/contributors/bnimmo.

[43] Ben Nimmo, The Breakout Scale: Measuring the Impact of Influence Operations (Brookings Institution, September 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Nimmo_influence_operations_PDF.pdf.

[44] An example of this type of Russian activity can be found in Finland. After Russia’s invasion of the Crimean Peninsula in February 2014, Russian trolls posted numerous responses to local news articles about the invasion and promoted messages favoring Russia. A study conducted in Finland found that many Finnish citizens who were exposed to these responses had difficulty formulating an opinion on the invasion due to the dissemination of conflicting information to which they were exposed.

[45] Embassy of Ukraine in the State of Israel (@UkraineInIsrael), “This is news that the Russian government spreads with the intention of accusing Ukaine to be a part of the Russians’ struggle against Israeli people,” Facebook, October 29, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/UkraineInIsrael/posts/736895988471963/.

[46] Carmel News (@AlexmehaCarmel), “A very interesting story: The communications channels in Russia reported weapons belonging to a border patrol in Mukachevo, Ukraine, were found with Hamas terrorists,” [in Hebrew] Telegram, October 12, 2023, https://t.me/alexmehacarmel/10176.

[47] Omer Benjakob, “Russian Pushes Gaza Disinfo With Spoofed Fox News Site and ‘Deep-Fake Israeli Soldiers,” Haaretz, November 20, 2023, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/security-aviation/2023-11-20/ty-article/.premium/deep-faked-soldiers-and-spoofed-websites-russian-campaign-pushes-gaza-disinformation/0000018b-ed5c-d36e-a3cb-fd5fadd90000.

[48] Insikt Group, Obfuscation and AI Content in the Russian Influence Network Doppelgänger Signals Evolving Tactics (Recorded Future, December 5, 2023), https://go.recordedfuture.com/hubfs/reports/ta-2023-1205.pdf.

[49] Microsoft Threat Intelligence, Digital Threats From East Asia Increase in Breadth and Effectiveness (Microsoft, September 2023), 6, https://query.prod.cms.rt.microsoft.com/cms/api/am/binary/RW1aFyW; ActiveFence, Generative AI The New Attack Vector for Trust and Safety (2023), 8, https://go.activefence.com/generative-ai-the-new-attack-vector-for-trust-and-safety; Katerina Sedova, Christine McNeill, Aurora Johnson, Aditi Joshi, and Ido Wulkan, AI and the Future of Disinformation Campaigns Part 2: A Threat Mode (Center for Security and Emerging Technology, December 2021), 24, https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/CSET-AI-and-the-Future-of-Disinformation-Campaigns-Part-2.pdf.

[50] An example of an in-depth discussion of the principles of strategic communications can be found in NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, Understanding Strategic Communications: NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence Terminology Working Group Publication No. 3 (Riga: NATO Strategic Communications Center of Excellence, 2023), https://stratcomcoe.org/publications/understanding-strategic-communications-nato-strategic-communications-centre-of-excellence-terminology-working-group-publication-no-3/285.

[51] Nir Dvori, “Concern in the Shin Bet: Iranian and Russian Agents Will Try to Interfere in the Elections,” N12 News, August 12, 2022, https://www.mako.co.il/news-military/2022_q3/Article-1a86a7b0cc29281026.htm.

[52] Yarden Vatikay and Libi Oz, “Oversharing and the Cognitive Campaign in the Digital Realm,” lecture at cyber influence conference, Tel Aviv University, March 14, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_SpxkogCQq0.

[53] Jon Roozenbeek, Sander vander Linden, Beth Goldberg, Steve Rathje, and Stephan Lewandowsky, “Psychological Inoculation Improves Resilience against Misinformation on Social Media,” Science Advances 8, no. 34 (August 2022), https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo6254.

[54] Tom Gerken, “Google to Run Ads Educating Users about Fake News,” BBC, August 25, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-62644550.

[55] Nir Gontarz, “‘Why Do You Select Which Foreign Journalists Can Enter Gaza?’ ‘I Have My Professional Considerations,’” [in Hebrew] Haaretz, February 15, 2024, https://www.haaretz.co.il/magazine/on-the-line/2024-02-15/ty-article/.highlight/0000018d-a7f2-da6e-af9f-affb4e5a0000.

[56] About the EU-HYBNET, see EU-HYBNET, “A Pan-European Network to Counter Hybrid Threats,” (n.d.) https://euhybnet.eu/.

[57] EU-HYBNET, EU-HYBNET 2nd Innovation and Standardisation Workshop (ISW) 8th November 2023, Valencia, Spain (n.d.), 4, https://euhybnet.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/EU-HYBNET_ISW-2023_Report_final.pdf.

[58] European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats.