Publications

INSS Insight No. 1888, August 18, 2024

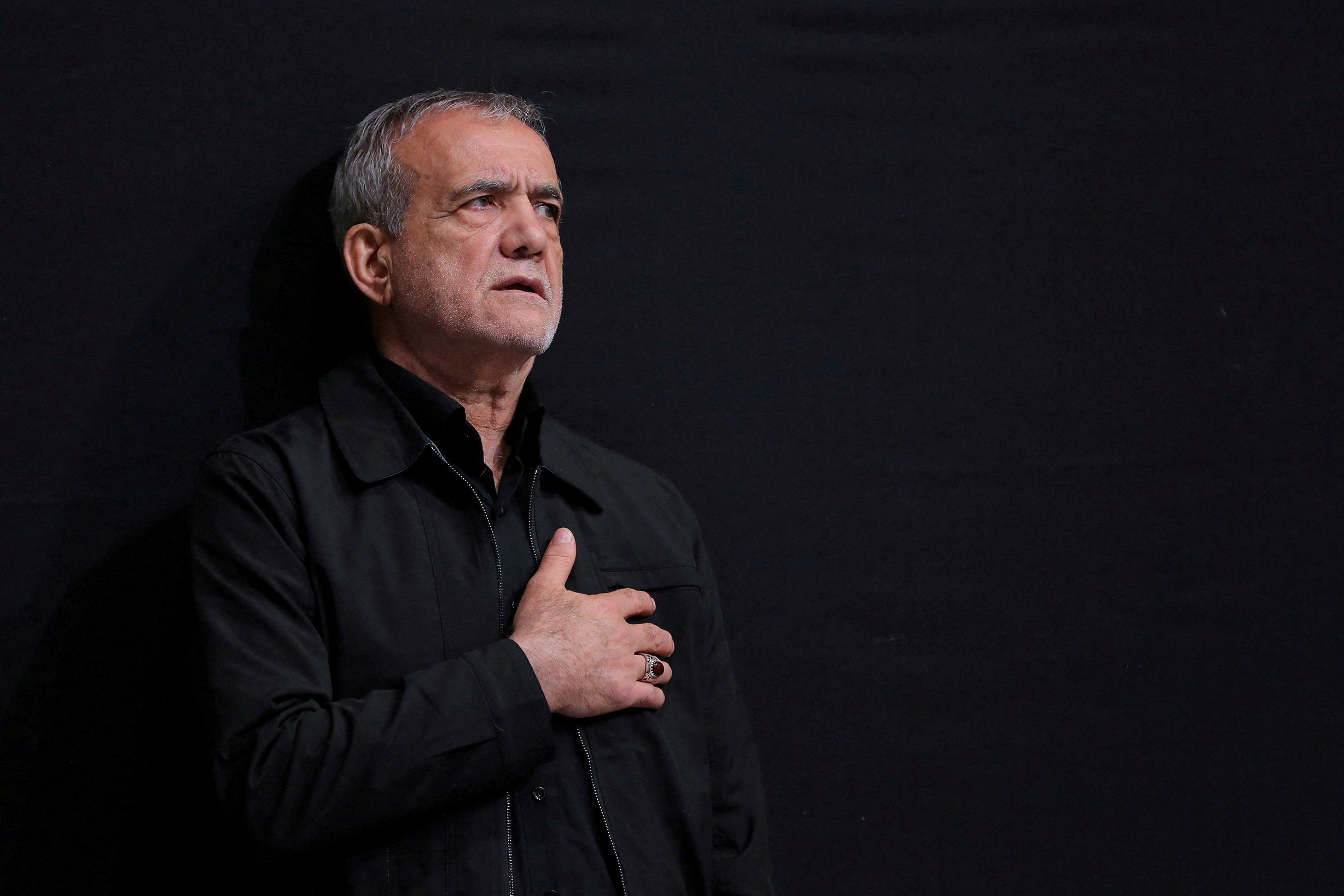

On August 11, 2024, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian submitted his proposed government to the Majlis for approval. Its composition reflects a balance between diverse political forces, both conservative and pragmatic alike, highlighting the constraints and limitations facing Pezeshkian as he navigates the main centers of power in Iran, led by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. The president has refrained from assigning ministers with distinctly reformist views to major government ministries, which the conservative establishment regards as sensitive. Instead, he has appointed more pragmatic ministers to other key ministries, including the foreign ministry. In doing so, Pezeshkian has signaled his preference for advancing economic reforms over political or civic reforms, reflecting his position as a centrist (a “conservative reformist”) —who is not committed to a liberal worldview. While the proposed government represents a trend toward moderation compared to the administration of former President Ebrahim Raisi, it is not expected to bring about significant changes in Iranian policy. Moreover, the inherent problems plaguing the Iranian economy, the president’s lack of experience, and his complex relationships with other major power centers raise doubts about his ability to address the fundamental issues facing the citizens of Iran.

On August 11, 2024, Iran’s new president, Masoud Pezeshkian, submitted a list of candidates nominated for ministerial posts in his government to the Iranian parliament (the Majlis). Each candidate’s appointment requires the approval of a majority of Majlis members, whereas the appointment of ministers serving in sensitive positions—including the foreign minister, the minister of intelligence, and the minister of the interior—also requires the approval from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Pezeshkian’s proposed government is composed largely of technocrats with extensive academic backgrounds. Eleven of the 19 nominated ministers hold doctoral degrees (some from Western universities), most in fields related to their respective ministries, and several also have administrative experience in these areas.

Most of the nominated ministers are politically affiliated with the pragmatic wing of the conservative camp. Seven served as ministers or deputy-ministers in the two previous governments of Hassan Rouhani (2013–2021), and six served as ministers and deputy-ministers in the previous government of Ebrahim Raisi (2021–2024). During the process of forming his government, Pezeshkian faced pressure from hardline conservative circles, urging him to avoid appointing ministers associated with the reformist camp, as well as from reformist circles, who expected the inclusion of reformists, women, young ministers, and minorities in his administration. These ministers are likely to advocate for changes in the political-civic sphere, including easing the enforcement of the Islamic dress code, lifting the filtering of social media, and removing some of the laws that discriminate against women and ethnic and linguistic minorities.

The composition of Pezeshkian’s proposed government reflects the constraints and limitations he faces, requiring him to balance diverse political forces within a broad “national government of consensus.” While Pezeshkian is beholden to the moderate wing of the reformist camp, which supported him during the election campaign, he also sought to avoid nominating controversial reformist ministers, who could provoke opposition from the conservative establishment, led by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, and other major centers of power, notably the Revolutionary Guards, the Majlis, and the religious establishment. To prevent opposition from the conservative right, Pezeshkian refrained from nominating reformist ministers to key ministries—the interior, intelligence, Islamic guidance, and justice, which are viewed as sensitive by the conservative clerical establishment. Moreover, Pezeshkian nominated ministers who had served in former President Raisi’s government, such as Esmail Khatib as the minister of intelligence and Amin Hossein Rahim as the minister of justice. For the position of interior minister, Pezeshkian nominated Eskandar Momeni, a former Revolutionary Guard officer and senior member of the law enforcement forces, who has previously expressed unequivocal support for enforcing the Islamic dress code for women. Pezeshkian’s efforts to avoid friction with the main centers of power are further evident in his decision to retain Mohamed Eslami as head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran and to nominate Aziz Nasirzadeh, who served as deputy head of the general staff of the armed forces and as commander of the regular army’s air force, as defense minister.

Pezeshkian’s decision not to appoint ministers with a reformist outlook to key government ministries responsible for domestic policy and law enforcement reflects his preference for advancing economic reforms over civic-political reforms. The president-elect’s ability to implement meaningful changes in areas such as Islamic enforcement, unblocking social media, releasing political prisoners, and strengthening civil society institutions is limited by the opposition of the clerical conservative establishment under Khamenei’s leadership. Furthermore, Pezeshkian himself is not considered a distinctly reformist politician; he is more accurately described as a centrist. However, during the election campaign, he expressed opposition to both increasing the punishment for women not wearing head coverings and blocking social media. Unlike former President Mohammad Khatami, Pezeshkian is not committed to a liberal worldview and is aligned with a political faction that can be described as “conservative reformists.” This faction emphasizes economic development and social justice over political liberties and civil rights.

At the same time, Pezeshkian nominated ministers identified as more pragmatic to government ministries that the conservative right views as less sensitive, such as the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Finance (entrusted to Abdolnaser Hemmati, who served as the Central Bank governor under President Rouhani), the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology, and the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare. For the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development, Pezeshkian nominated Farzaneh Sadegh-Mavaljerd. If approved by the Majlis, Sadegh-Mavaljerd would become the second female minister to serve in the Iranian government since the Islamic Revolution, following Marzieh Vahid-Dastjerdi, who served as minister of health in President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s second term (2009–2013).

The nomination of Abbas Araghchi, a former deputy foreign minister and a key member of the nuclear negotiating team under President Rouhani, reflects the new president’s intention to fulfill his promise to return to negotiations with the United States and reach agreements with the international community regarding Iran’s nuclear program, with the goal of lifting economic sanctions. Araghchi, a veteran professional diplomat from a conservative religious family in Tehran, is acceptable to conservative circles, as well, despite his unequivocal support for the nuclear agreement and dialogue with the United States. However, it is important to note that the president’s ability to advance dialogue with the United States will largely depend on Supreme Leader Khamenei’s willingness to be flexible and reconsider his principled opposition to an agreement with the United States. The outcome of the upcoming US presidential elections will also significantly influence this process.

The proposed makeup of the Iranian government is already facing criticism from reformist circles. The primary criticism concerns the president’s decision not to include a larger number of ministers with distinctly reformist views, as well as women and young people, with the average age of ministers in the proposed government nearing 60. The absence of representatives from Sunni religious minorities has also sparked criticism, especially given the strong support Pezeshkian received in regions populated by ethnic-linguistic minorities, some of whom are Sunni, and the fact that he himself is the son of an Azeri Turkish father and a Kurdish mother. The most significant expression of dissatisfaction with the government’s composition came from former Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, who resigned shortly after being appointed as the new vice president for strategic affairs. In an announcement posted on the social media platform X, Zarif expressed frustration with the government’s makeup, stating that only three of the ministers were the first choices of the committee established by the president to nominate candidates for ministerial posts. In contrast, several politicians affiliated with the centrist faction of the reformist movement expressed qualified support for the proposed government, arguing that the new government's primary test would be its ability to solve the challenges facing the Islamic Republic, rather than its composition.

In conclusion, Pezeshkian’s proposed government reflects a departure from Raisi’s administration, particularly regarding the political perspectives of its ministers. Although it is not expected to bring significant changes in Iranian policy, it may hinder the strengthening of hardliners within decision-making circles and prevent their complete takeover of governing authorities in the coming years. First and foremost, it demonstrates a desire to achieve balance among the major political factions to ensure the president’s cooperation with the political centers of power. This cooperation is seen as crucial for his success in office. At this stage, it is evident that the president prefers to focus on addressing the fundamental problems facing Iran, primarily the economic crisis, while avoiding clashes with other centers of power, which appear to view him with great suspicion due to the positions he expressed during the election campaign.

As for the Iranian public, it is uncertain whether the government’s composition alone will lead to a crisis of expectations, especially considering that the citizens’ initial expectations of Pezeshkian, particularly among the younger generation, were already low. Public support for the president-elect will largely depend on his policies in practice, the achievements of his government, and his ability to fulfill his promises. Conversely, his failure may exacerbate the legitimacy crisis that the Iranian regime has faced in recent years. This crisis was particularly evident in the unprecedentedly low voter turnout in the recent elections for the Majlis in March 2024 and for the presidency in June–July 2024. Given the inherent problems plaguing the Iranian economy, the president’s lack of experience, and his complex relationship with other major centers of power, such as the Office of the Supreme Leader and the Revolutionary Guards, it remains doubtful whether the new president will be able to propose solutions to Iran’s fundamental problems and bring about genuine improvements in the quality of life for Iranian citizens.